Abstract

We made substantial advances in the implementation of a rapamycin-triggered heterodimerization strategy. Using molecular engineering of different targeting and enzymatic fusion constructs and a new rapamycin analog, Rho GTPases were directly activated or inactivated on a timescale of seconds, which was followed by pronounced cell morphological changes. As signaling processes often occur within minutes, such rapid perturbations provide a powerful tool to investigate the role, selectivity and timing of Rho GTPase–mediated signaling processes.

The Rho family of small GTPases has been shown to function as molecular switches in several physiological contexts such as cell migration, phagocytosis, adhesion and secretion, as well as transcriptional control1,2. Rho GTPase signaling processes are known to have considerable crosstalk3, and they regulate cellular events in a concerted and integrated manner that is only partially understood. Previous studies addressing specific roles of small GTPases often relied on the expression of constitutively active and inactive mutated forms of Rho, Cdc42 and Rac. But these GTPases have limited use because they are active for time periods that exceed the duration of the signaling process they control so that transient activities cannot be investigated. Thus, rapid conditional perturbation would be more useful for time-resolved studies of these signaling proteins.

A conceptually elegant approach for Rac and Cdc42 activation that takes advantage of rapamycin-induced heterodimerization has been reported4–6. In this study, researchers conjugated Rho GTPase proteins with a rapamycin-binding domain of mTOR (FRB) and the cytoplasmic region of a transmembrane receptor was conjugated with a FK506-binding protein (FKBP). Their goal was to activate downstream processes by using a small molecule–dependent translocation of mutant Rho GTPases to the plasma membrane. Rac or Cdc42 membrane recruitment in this system, however, was not sufficient to trigger phagocytosis or membrane extension and substantial physiological responses were only induced after clustering of many receptors using antibody-coated beads. We have developed a more rapid and direct perturbation method for Rho GTPases by optimizing the inducible plasma membrane targeting, synthesizing a rapamycin analog that can trigger rapid plasma membrane translocation and engineering different enzymatic fusion constructs.

To evaluate how to best target Rho GTPases to the plasma membrane, we tested a Lyn N-terminal sequence not previously used for heterodimerization (Supplementary Methods online). The ability of this sequence (GCIKSKGKDSA) to target proteins to the plasma membrane was compared to that of a previously used Src N-terminal sequence (GSSKSKPKDPSQR) by fusing these signal sequences to CFP (Lyn11-CFP) and YFP (Src13-YFP), respectively. When these proteins were co-expressed in NIH3T3 cells, there was substantially more plasma membrane localization of Lyn11-CFP (Supplementary Fig. 1 online). Similar observations were made when the two signal sequences were fused to FKBP, and these constructs were expressed in rat basophilic leukemia cells and detected by antibody staining (Supplementary Fig. 1). Accordingly, we decided to use Lyn11 as a membrane targeting signal.

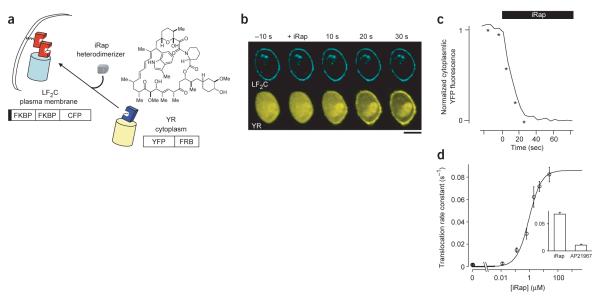

We then engineered two chimeric proteins, Lyn11-FKBP-FKBP-CFP (LF2C) and YFP-FRB (YR) (Fig. 1a), expressed them in RBL cells and monitored the ligand-induced heterodimerization and plasma membrane translocation as a function of time. Rather than applying rapamycin, we initially used AP21967, an analog developed at ARIAD Inc. to selectively interact with a mutant FRB domain (here used for the YR constructs). Addition of 5 μM AP21967 caused YR translocation to the site of LF2C with a relatively slow rate constant of 0.011 ± 0.001 s−1 (time constant, τ, 90 ± 8 s). Upon evaluation of several cell-permeable rapamycin analogs that we prepared, faster translocation was observed using a new indole-modified analog, iRap (Fig. 1a,b), which induced translocation with a rate constant of 0.067 ± 0.004 s−1 (τ, 15 ± 1 s; Fig. 1c) with an effective concentration for half-maximum response (EC50) value of 940 nM for membrane translocation (Fig. 1d). Using these fusion constructs and the new rapamycin analog, this dimerization system is more effective and has a ~46-fold faster response than a previously published system7.

Figure 1.

Rapid binding of a cytoplasmic YFP-tagged FRB to a plasma membrane targeted FKBP construct by addition of a rapamycin analog. (a) Schematic representation of the inducible plasma membrane translocation strategy using iRap (solid box; Lyn11). (b) Series of dual confocal images of RBL cells expressing plasma membrane–localized CFP-tagged FKBP (LF2C) and YFP-tagged FRB (YR). iRap triggered a marked translocation of cytosolic YR to the plasma membrane. Live cell dual color measurements were performed on a spinning-disc confocal microscope. For CFP and YFP excitations, we used a helium-cadmium laser and an argon laser, respectively. Fluorescence images were taken every 3 or 5 s during the translocation assay. Scale bar, 10 μm. (c) Normalized fluorescence intensity of YR construct in the cytoplasm before and after addition of iRap. Time points indicated by asterisks correspond to confocal fluorescence images shown in b. (d) Rate constants derived from the membrane translocation timecourse were calculated for measurements taken in the presence of various iRap concentrations. Inset, the rate constants (s−1) of membrane translocation induced by 5 μM iRap and AP21967, respectively. Error bars, s.e.m. (n ≥ 3).

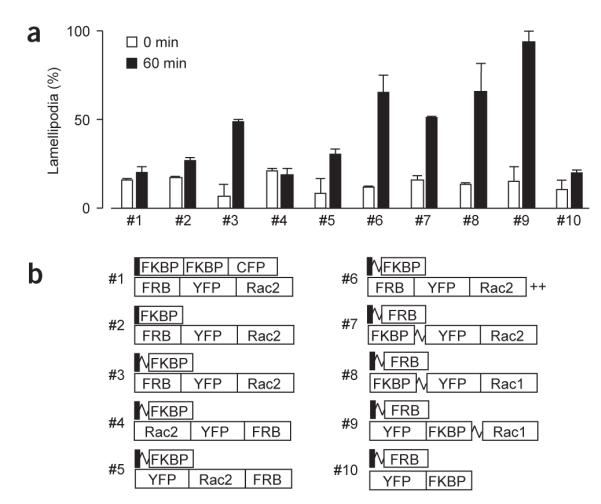

To investigate whether membrane recruitment translates into rapid activation of Rho GTPases, we engineered a fusion construct comprising an FRB domain and a constitutively active Rac2 (Rac2CA) that lacked the C-terminal CAAX box (RY-Rac2CA). We expressed this construct with LF2C in NIH3T3 cells. After addition of 5 μM iRap for 60 min, cells were fixed, stained with phalloidin and inspected for lamellipodia formation. Unexpectedly, only 20.1 ± 3.4 % of transfected cells had Rac2-associated morphological changes such as membrane ruffling or lamellipodia extension (construct pair #1; Fig. 2). Because the geometry of the translocated Rac protein might not be correct for target activation, we made predictions based on the known published structures8, designed a series of fusion constructs (Fig. 2b) with a potentially more active orientation, and then tested them for iRap-induced lamellipodia formation. Removal of the CFP tag and the second FKBP domain from LF2C (#2), as well as the addition of a flexible linker between Lyn11 and FKBP (#3), improved lamellipodia formation (26.8 ± 1.8% and 48.7 ± 1.3%, respectively). When the position of Rac2 within the chimeric protein was permutated (#3–#5), we found that Rac2 was most functional at the C terminus of the chimeric protein (48.7 ± 1.3%, 18.8 ± 3.4% and 30.3 ± 3.3%, for constructs #3–5, respectively). These results, as well as those for construct #6 in which a C-terminal membrane targeting polybasic sequence was added (65.3 ± 9.7%), indicated that the precise three-dimensional configuration of Rac2 is critical. Interestingly, FRB and FKBP binding partners could also be exchanged (#7, 51.0 ± 1.0%) and Rac1 seemed to be better than Rac2 in inducing lamellipod extension (#8, 65.9 ± 15.9%). Of all the pairs tested, the strongest iRap-induced lamellipodia extension was observed using a Lyn11-targeted FRB (LDR) at the plasma membrane and a YFP-FKBP-Rac1 fusion construct (YF-Rac1CA) in the cytoplasm (#9, 93.9 ± 6.0%). As controls, we tested that the observed lamellipod formation could not be induced by iRap in the absence of the expressed constructs or by membrane recruitment of cytoplasmic fusion proteins without Rac activity (#10, 19.8 ± 1.6%).

Figure 2.

Development of an effective hetero-oligomerization strategy for small GTPase activation. (a) Engineering and testing of FRB, FKBP and Rac constructs to identify suitable heterodimerization pairs for inducing lamellipodia formation. NIH3T3 cells were transfected with each construct pair, stimulated with 5 μM iRap for 60 min, and then fixed and stained with phalloidin. The values shown are numbers of transfected cells with induced lamellipodia. The morphology assay of fixed NIH3T3 cells was performed as described previously14 in the presence of 5 μM iRap at 37 °C. Error bars, s.e.m. (n ≥ 2, 25 ± 2 cells). (b) Schematics of the constructs tested in a (squiggle, flexible linker; ++, polybasic residues GKKKK).

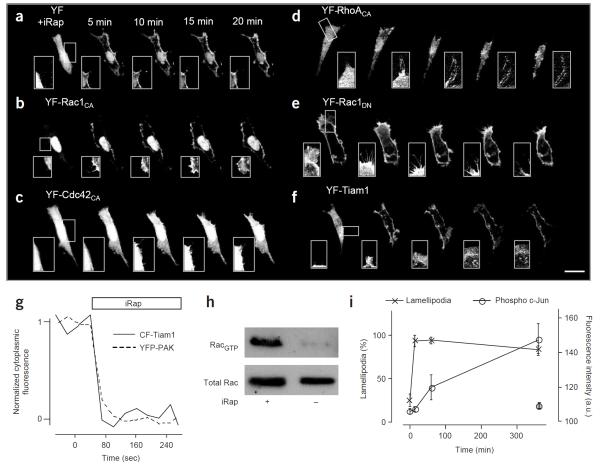

Live-cell imaging of cells expressing LDR and YF-Rac1CA (#9) revealed a striking and rapid induction of lamellipodia formation upon addition of 5 μM iRap, whereas no major changes were observed with control YF (#10; Fig. 3a,b and Supplementary Videos 1 and 2 online). The rate constant of translocation for the LDR and YF-Rac1CA system was 0.079 ± 0.013 s−1 (τ, 13 ± 2 s) and a marked induction of lamellipodia could be observed within minutes.

Figure 3.

Rapid effects on cell morphology and downstream effectors by heterodimerization. (a–f) Time series of confocal fluorescence images of NIH3T3 cells expressing different pairs of constructs: LDR with YF (a), YF fused to constitutively active Rac1 (b), Cdc42 (c), RhoA (d), Rac1DN (e) or GEF domain of Tiam1 (f). The first image was taken before addition of 5 μM iRap. In the case of Cdc42, neuronal Wiscott-Aldrich syndrome protein (N-WASP) was coexpressed to increase the potential ability of cells to induce filopodia formation15. Likewise, cells expressing Rac1DN were pretreated with 10% serum to induce lamellipodia. Inset images highlight a site that shows marked morphological changes (except for the control in a). For the live cell morphology assay, fluorescence images were taken every 30 s with minimal laser power and exposure time to reduce photoinduced damage of the actin cytoskeleton. Scale bar, 20 μm. (g) Kinetic analysis of the translocation of CF-Tiam1 and YFP-PAK to the plasma membrane upon addition of iRap. (h) CF-Tiam1 translocation activates endogenous Rac1. NIH3T3 cells transfected with CF-Tiam1 and LDR were incubated for 30 min in the presence or absence of iRap. Rac1 activity was monitored using pull-down of GTP-bound Rac with a Rac-binding domain coupled to agarose beads. (i) Phosphorylation at Ser63 of c-Jun was detected using nuclear staining with a phosphospecific antibody. The c-Jun phosphorylation level was measured in cells expressing YF-Rac1CA (open circle), and in nontransfected control cells from the same images (gray circle). Lamellipodia formation was evaluated in the same cells and plotted (cross symbol) to compare the timecourse of c-Jun phosphorylation to that of the appearance of morphological changes. Error bars, s.e.m.

Other Rho family members such as Cdc42 and RhoA are also known to regulate the reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton. Whereas Cdc42 induces filopodia, RhoA induces stress fibers, giving rise to cell contraction. In order to test whether our translocation strategy can be used for these Rho family members, Rac1CA was replaced by constitutively active Cdc42 and RhoA in the YF construct. After addition of iRap, cells expressing YF-Cdc42CA formed filopodia, whereas cellular contractions were observed in cells expressing YF-RhoACA (Fig. 3c,d and Supplementary Videos 3 and 4 online).

We then investigated whether this approach is also suitable for inhibiting instead of activating signaling pathways and replaced Rac1CA with its dominant negative mutant, Rac1DN. When YF-Rac1DN and LDR were coexpressed in NIH3T3 cells that have been mildly activated in the presence of 10% serum, iRap addition induced a marked reduction of lamellipodia (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Video 5 online). This suggests that translocation of dominant negative constructs can be used to block native signaling pathways. When the same YF-Rac1DN experiment was performed in cells cotransfected with Rac1CA to induce more robust lamellipodia, translocation of YF-Rac1DN made lamellipodia unstable and gave rise to newly formed filopodia extending out from the edge of lamellipodia (Supplementary Fig. 1). This is consistent with a previous report9, which suggested that the Cdc42 activity becomes unmasked in the presence of Rac1DN. To further assess the involvement of Cdc42, the cells were transfected with a dominant negative form of Cdc42 as well as Rac1CA. iRap-induced Rac1DN translocation caused unstable lamellipodia but no filopodia formation (Supplementary Fig. 1).

The above studies used rapid translocation of exogenous Rac activity to perturb the cytoskeletal regulatory system. As it can be desirable to activate endogenous Rac activity, we investigated whether we can induce the translocation of a Rac GEF activity to activate native Rac proteins. To generate an inducible GEF activity, we fused the DH-PH domain10 of the GEF protein Tiam1 to FKBP. In NIH3T3 cells expressing LDR and this new GEF probe, a robust lamellipodia formation could be rapidly induced (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Video 6 online). The marked lamellipodia formation triggered by this native Rac activator was even more pronounced than the one triggered by the Rac1CA construct.

We determined whether endogenous Rac was activated by the Tiam1 probe by using a previously described fluorescent biosensor for activated Rac based on the Rac-binding domain of p21-activated kinase (YFP-PAK)11. Upon addition of iRap, YFP-PAK translocated with similar kinetics when compared to CF-Tiam1 (Fig. 3g), strongly suggesting that endogenous Rac is activated at the plasma membrane by the translocated CF-Tiam1. The activation of Rac was confirmed using a pull-down assay (Fig. 3h), demonstrating the endogenous Rac can also be activated with this method in a population of cells for subsequent biochemical analysis. The striking morphology change triggered by the Tiam1 probe suggests that native Rac and possibly other small GTPase activities can be effectively controlled by the translocation of catalytic GEF domains.

Finally, we used a well-known downstream effector, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and tested whether the induced YF-RacCA translocation leads to the phosphorylation of c-Jun. When cells were transfected with LDR and CF-Rac1CA and treated with iRap, the amount of phophorylated c-Jun increased in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 3i). The timecourse of iRap-induced JNK activity was then compared to that of the appearance of morphological changes. Whereas morphological changes occurred on the order of seconds to minutes, JNK phosphorylation took minutes to hours (Fig. 3i), consistent with a previous report demonstrating that JNK activity is independently regulated from the actin cytoskeleton pathway12,13.

In the present study, we have considerably evolved the rapamycin-based heterodimerization technique by improving the construct design and by using a new rapamycin analog. Using this system, one can now rapidly activate and inactivate Rho small GTPases on a timescale of seconds, making inducible heterodimerization a powerful approach to investigate the role, selectivity and timing of different Rho GTPase–mediated signaling processes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank ARIAD Pharmaceuticals for providing AP21967, as well as plasmids encoding FKBP and FRB. We also thank H. Sugimura and M. Fivaz for the generous gift of Tiam1 and Lyn11-CFP constructs, respectively, to F. Fernandez, M. Fivaz and A. Hahn for critical review of this manuscript, and to M. Fivaz and members of the M. Scott laboratory for technical advice on the pull-down assay. This study was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (GM063702 to T.M. and GM-068589 to T.J.W.). T.I. is a recipient of a fellowship from the Quantitative Chemical Biology program.

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Methods website.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Takai Y, et al. Physiol. Rev. 2001;81:153–208. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Etienne-Manneville S, et al. Nature. 2002;420:629–635. doi: 10.1038/nature01148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burridge K, et al. Science. 1999;283:2028–2029. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5410.2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castellano F, et al. J. Cell Sci. 2000;113:2955–2961. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.17.2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castellano F, et al. Methods Enzymol. 2000;325:285–295. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)25450-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crabtree GR, et al. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1996;21:418–422. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(96)20027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terrillon S, et al. EMBO J. 2004;23:3950–3961. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi J, et al. Science. 1996;273:239–242. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiménez C, et al. J. Cell Biol. 2000;151:249–261. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.2.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michiels F, et al. J. Cell Biol. 1997;137:387–398. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.2.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson G, et al. Biochemistry. 1998;37:7885–7891. doi: 10.1021/bi980140+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamarche N, et al. Cell. 1996;87:519–529. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81371-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joneson T, et al. Science. 1996;274:1374–1376. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5291.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heo WD, et al. Cell. 2003;113:315–328. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00315-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miki H, et al. Nature. 1998;391:93–96. doi: 10.1038/34208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.