Abstract

Understanding how culture and familial relationships are related to Mexican-origin youths’ normative sexual development is important. Using cultural-ecological, sexual scripting, and risk and resilience perspectives, the associations between parent-adolescent relationship characteristics, adolescents’ cultural orientations and familism values, and sexual intentions among 246 Mexican-origin adolescents (50% female) were investigated. Regression analyses were conducted to examine the connections between youths’ cultural orientations and familism values and their intentions to engage in sexual intercourse and to test the moderating role of parent-adolescent relationship characteristics and adolescent sex. For boys, under conditions of high maternal acceptance, higher Anglo orientations and higher Mexican orientations were related to greater sexual intentions. For girls, familism values played a protective role and were related to fewer sexual intentions when girls spent less time with their parents. The findings highlight the complex nature of relationships between culture, family relationships, and youths’ sexual intentions and different patterns for girls versus boys.

Sexual development is a normative aspect of adolescence (Graber, Brooks-Gunn, & Galen, 1998); however, the majority of research has focused on youths’ risky sexual behaviors (Diamond & Savin-Williams, 2009). This is particularly true for Latino youth (Raffaelli & Iturbide, 2009). Latino youth have higher teen birth rates than any other ethnic group and higher rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) than non-Latino Whites (National Vital Statistics, 2005). To gain insight into Latino youths’ sexual risk taking, scholars are calling for research on normative sexual development for Latino youth (Raffaelli, & Iturbide, 2009). An aspect of youths’ normative sexual development is their intentions to engage in sexual intercourse. Despite the common belief that adolescents’ sexual behaviors are impulsive, there is evidence that adolescents’ intentions to engage in sexual activities are related to their actual behaviors (Gillmore et al., 2002). Adolescents’ intentions have predicted their sexual behaviors in several domains, including pregnancy and sexual intercourse (East, Khoo, & Reyes, 2006). Given the strong theoretical (e.g., Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) and empirical (e.g., East et al., 2006) support linking intentions to behaviors, examining adolescents’ intentions to engage in sexual intercourse is a necessary step in understanding the development of adolescents’ sexuality.

The purpose of the present study was to investigate the family and cultural correlates of Mexican-origin adolescents’ sexual intentions. Drawing on cultural-ecological (Ogbu, 1981) and sexual scripting (e.g., Longmore, 1998) perspectives, which emphasize the importance of the cultural context, our first goal was to examine how adolescents’ cultural orientations (i.e., Mexican and Anglo orientations) and familism values were related to their sexual intentions. Informed by a risk and resilience perspective, our second goal was to investigate the moderating roles of mother- and father-adolescent relationship qualities in the linkages between adolescents’ cultural orientations/values and their sexual intentions. We also tested the moderating role of adolescent sex as part of our second goal.

This study was designed to understand the role of culture in Mexican-origin adolescents’ sexual intentions by using an ethnic-homogeneous design (McLoyd, 1998) and focusing on how within-group variability in cultural processes (e.g., the extent to which youth endorse familism values or exhibit Mexican or Anglo cultural orientations) are linked to diversity in youths’ sexual intentions in a specific cultural context. Comparisons of youth from different Latino backgrounds reveal differences in their sexuality-related outcomes. Mexican-origin girls, for example, are more likely to experience a teen birth as compared to Cuban and Puerto Rican adolescent girls (Ryan, Franzetta, & Manlove, 2005). Further, Latino subgroups are diverse with regard to family background and cultural factors (e.g., SES, degrees of enculturation and acculturation; Roosa, Morgan-Lopez, Cree, & Specter, 2002), all factors that may be related to adolescents’ sexual development. It is important, therefore, to examine the links between cultural experiences and sexuality within Latino subgroups.

Adolescents’ Cultural Orientations and Familism Values

Cultural orientations and values are important because adolescents learn how to enact sexual roles based on their cultural context (O’Sullivan & Meyer-Bahlburg, 2003), and adolescents with different cultural orientations and familism values may enact different sexual roles. Support for the role of culture in sexuality, particularly sexual decision-making processes, has been provided by qualitative work with Latina adolescents (Villarruel, 1998). This work has revealed the importance of including assessments of culture in future studies on Latina youths’ sexuality, which are consistent with the goals of this study.

A number of scholars argue that cultural processes are multidimensional and must take into account cultural adaptation in reference to both the host and ethnic culture (Gonzales, Knight, Morgan-Lopez, Saenz, & Sirolli, 2002). Yet, empirical studies typically rely on single dimensions and “proxy” measures (e.g., language fluency, nativity). Several researchers have reported that language preference (i.e., English versus Spanish) was related to sexual experiences, revealing that English-speaking Latinas were younger when they experienced their sexual debut (i.e., time of first sexual intercourse) and were at greater risk of having early sex compared to Spanish-speaking Latinas (Adam, McGuire, Walsh, Basta, & LeCroy, 2005; Ford & Norris, 1993; Upchurch, Aneshensal, Mudgal, & McNeely, 2001). In the present study, we build on existing work by examining how youths’ cultural orientations in reference to both Mexican and Anglo (U.S.) cultures are linked to their sexual intentions.

In addition to the importance of studying Mexican and Anglo cultural orientations, familism values are a salient aspect of Mexican culture (Cauce & Domenech-Rodríguez, 2002; Marín & Marín, 1991) and may be important in the development of adolescents’ sexual intentions. The value of familism encompasses the sense of loyalty and attachment that individuals feel to their nuclear and extended families (Marín & Marín, 1991), and the responsibility they have to contribute to the family’s well-being (Cauce & Domenech-Rodríguez, 2002). Familism has been linked with positive youth adjustment in prior work (Fuligni, Tseng & Lam, 1999; Kaplan, Napoles-Springer, Steward, & Perez-Stable, 2001), highlighting the potential protective nature of familism values for Latino youth. Researchers have speculated on the role that familism plays in adolescents’ sexual decision-making (e.g., Perkins & Villarruel, 2000). In her focus group interviews, Villarruel (1998) found that many Latinas indicated that they intended to remain virgins and delay sexual initiation to protect their families.

The Moderating Role of Parent-Adolescent Relationship Characteristics

We drew on a risk and resilience perspective (e.g., Masten, Best, & Garmezy, 1990) to examine the moderating roles of parental acceptance and involvement in the connections between adolescents’ cultural orientations/values and their sexual intentions. According to a risk and resilience model, support in the parent-adolescent relationship is an important correlate of adolescent adjustment (Bámaca, Umaña-Taylor, Shin, & Alfaro, 2005; Crouter, Head, McHale, & Tucker, 2004). Close relationships with parents have been linked to positive adjustment among Latino youth (Bámaca et al., 2005), and to more shared family time in European American families (Crouter et al., 2004). Supportive relationships and shared family time may be related to more socialization opportunities and the transmission of values from parents to their children (Christopher, 2001). Accumulating evidence suggests that close and involved relationships with parents are associated with less engagement in deviant and risk-taking activities (Bámaca et al., 2005; Crouter et al., 2004). Youth who describe more positive relationships with parents and spend more time with parents may be less motivated and have more limited opportunities to engage in deviant and risky behaviors.

Most existing studies focus on mothers, ignoring fathers’ contributions to family dynamics and youth adjustment. Researchers have noted the importance of examining the role of both mothers and fathers because mothers’ and fathers’ relationships with adolescents are unique (Parke & Buriel, 1998). For example, Mexican American father-adolescent relationships are characterized by less physical affection and open communication than mother-adolescent relationships (Crockett, Brown, Russell, & Shen, 2007). Additionally, there are structural differences, in that relationships with fathers are described as more “peer-like” (i.e., more egalitarian) than relationships with mothers (Parke & Buriel, 1998). Given the potentially different relationships that mothers and fathers have with their sons and daughters, we explored how support and involvement with mothers and with fathers moderated the associations between cultural orientations and familism values and sexual intentions.

The Role of Adolescent Sex

There are several reasons to consider the role of adolescent sex in Latino adolescents’ sexual behaviors. First, there is consistent evidence that Latino boys are more likely to have sexual intercourse (e.g., Huerta-Franco & Malcara, 1999) and to have four or more sexual partners compared to Latina girls (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008). Second, sex has been described as an organizing feature of family life in Mexican culture (Cauce & Domenech Rodriguez, 2002) with potentially different socialization experiences for girls versus boys. There is evidence, for example, that parents are more protective of daughters than of sons (Azmitia & Brown, 2002), that girls had more restrictions placed on their activities outside the home by parents as compared to their brothers (Ayala, 2006), and that boys were encouraged by parents to date more than were girls (Villarruel, 1998). Therefore, we included adolescent gender as a potential moderator of the associations among culture, family, and sexual intentions.

Hypotheses

Drawing on cultural-ecological, sexual scripting, and risk and resilience perspectives and the empirical literature, we developed five hypotheses. First, given previous findings linking acculturation and sexuality (Adam et al., 2005; Ford & Norris, 1993; Upchurch et al., 2001), we expected that Anglo orientation would be positively associated with youths’ sexual intentions and Mexican orientation would be negatively associated with youths’ intentions for sex. Second, because many Latina adolescents reported that they remained virgins to protect the reputations of their families (Villarruel, 1998), we expected a negative association between familism values and adolescents’ sexual intentions. Third, we expected that parental acceptance and time spent with parents would function as protective factors in the associations between adolescents’ cultural orientations and familism values and their intentions to engage in sex when cultural orientations and values place youth at risk. In particular, when adolescents have strong ties to Anglo culture, fewer ties to Mexican culture, or weak familism values, supportive relationships with parents and time spent with parents may serve a protective role through the socialization that occurs within the parent-adolescent relationship context. Fourth, how parent-adolescent relationship characteristics moderate the associations between cultural orientations and values and sexual intentions also may differ for boys and girls. We expected that the associations between both familism values and Mexican orientations and sexual intentions would be stronger when girls as compared to boys reported close and involved relationships with parents, given the emphasis on family relationships for girls in Mexican culture (Azmitia & Brown, 2002). Fifth, because the transmission of values (e.g., emphasis on traditional male roles) is more likely to occur when youth report supportive relationships with parents (Christopher, 2001), we anticipated that, for boys reporting high levels of acceptance and time spent with parents, there would be a positive relationship between Mexican orientation and sexual intentions.

Method

Participants

The data came from a study of family socialization and adolescent development in Mexican-origin families (Updegraff, McHale, Whiteman, Thayer, & Delgado, 2005). The 246 participating families were recruited through schools in and around a southwestern metropolitan area. Criteria for participation were as follows: (1) mothers were of Mexican origin; (2) a 7th grader was living in the home and not learning disabled; (3) an older sibling was living in the home (in all but two cases, the older sibling was the next oldest child in the family); (4) biological mothers and biological or long-term adoptive fathers lived at home (all non-biological fathers had been in the home for a minimum of 10 years); and (5) fathers worked at least 20 hours/week. Most fathers (i.e., 93%) also were of Mexican origin.

To recruit families, letters and brochures describing the study (in both English and Spanish) were sent to families, and follow-up telephone calls were made by bilingual staff to determine eligibility and interest in participation. Families’ names were obtained from junior high schools in five school districts and from five parochial schools. Schools were selected to represent a range of socioeconomic situations, with the proportion of students receiving free/reduced lunch varying from 8% to 82% across schools. Letters were sent to 1,856 families with a Hispanic 7th grader who was not learning disabled; however, for 396 families (21%), the contact information was incorrect and repeated attempts to find updated information were unsuccessful. Eligible families (n = 421) represented 23% of the initial rosters (n = 1856), 29% of those we were able to contact (n = 1460), and 32% of those we were able to contact and screen (n = 1314). Of those eligible, 284 agreed to participate (67% of eligible families), 95 refused (23% of eligible families), and 42 moved between the initial screening and schedule call and no updated contact information was available (10% of eligible families). Interviews were completed by 246 families (of the 284 who agreed to participate). We did not complete interviews with 38 families (13% of the families who agreed to participate) because they were not locatable at the time of scheduling or were unwilling to participate or not home (repeatedly) when the interview team arrived at their home. Because the target sample size (N = 240) was surpassed, the latter group was not pursued.

Families represented a range of education and income levels, from poverty to upper class. The percentage of families that met federal poverty guidelines was 18.3%, a figure similar to the 18.6% of two-parent Mexican American families living in poverty in the county from which the sample was drawn (U.S. Census, 2000). Median family income was $40,000 (for two parents and an average of 3.39 children). Mothers and fathers had completed an average of 10 years of education (M = 10.34; SD = 3.74 for mothers, and M = 9.88; SD = 4.37 for fathers). Sixty-six percent of mothers and 68% of fathers completed the interview in Spanish. Most parents had been born outside the U.S. (71% of mothers and 69% of fathers). Older siblings were 50% female and 15.70 years of age (SD = 1.6; range 13 to 21 years of age; modal age was 15; 16% were in 8th grade, 31% were in 9th grade, 20% were in 10th grade, 16% were in 11th grade, 9% were in 12th grade, and 2% were beyond high school). Forty seven percent had been born outside the U.S, and 82% were interviewed in English. The present analyses focused only on older siblings because there was little variability in younger siblings’ sexual intentions.

Procedures

Data were collected during home interviews and a series of telephone interviews. Home interviews lasted an average of two hours for adolescents. Parents reported on background characteristics and adolescents reported on their family relationships and cultural orientations and values. Interviews were conducted individually using laptop computers by bilingual interviewers. Questions were read aloud due to variability in family members’ reading levels.

During the weeks following the home interview, 7 nightly telephone interviews were conducted (5 weekday nights and 2 weekend nights). Participants reported on their daily activities based on a cued recall strategy (McHale, Crouter, & Bartko, 1992). From these data, time spent with parents was calculated.

Measures

All measures were forward- and back-translated for local Mexican dialect according to a procedure developed by Foster and Martinez (1995).

Sexual intentions

Adolescents reported on their intentions to engage in sexual intercourse (e.g., “How likely is it that you will have sexual intercourse in the next year?”) using the average score of a 5-item measure with response options ranging from 1 (very unlikely/very unsure) to 5 (very likely/very sure). Four items were used from East (1998) and an additional item was included to appropriately represent boys’ sexual intentions (i.e., “How likely is it that you would try to persuade someone to have sex with you?”). Cronbach’s alphas were .88 for English-speaking and .92 for Spanish-speaking youth. Higher scores represented greater sexual intentions.

Anglo and Mexican orientation

Adolescents rated their Anglo and Mexican orientations using the ARSMA-II (Cuéllar, Arnold, & Maldonado, 1995). The ARSMA-II includes two subscales capturing orientations to Anglo (13 items) and Mexican (17 items) culture. Participants responded to items using a 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely often or almost always) on each subscale. A sample item for the Anglo orientation scale is “I like to identify myself as an Anglo American,” and a sample item for the Mexican orientation scale is “My family cooks Mexican food.” Cronbach’s alphas were .75 and .90 for English-speaking youth and .85 and .84 for Spanish-speaking youth for the Anglo and Mexican orientation subscales, respectively. Higher scores represented greater cultural orientations on these average scale scores.

Familism

Familism values were assessed using the familism subscale of the Mexican American Cultural Values Scale (Knight et al., 2010). Three conceptual domains were assessed on this 16-item measure: (1) support and emotional closeness (e.g., “Family provides a sense of security because they will always be there for you”); (2) obligations (e.g., “A person should share his/her home if a relative needs a place to stay”); and (3) family as referent (e.g., “Children should be taught to always be good because they represent the family.”). Adolescents responded on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) scale. Five items were adapted from Sabogal, Marín, Otero-Sabogal, Vanoss Marín, and Perez-Stable (1987) and the remaining items were developed through focus groups with Mexican American families. The 16 items were averaged to create a scale score with higher scores indicating higher familism values. Cronbach’s alphas for adolescents’ familism values were .89 for English-speaking youth and .93 for Spanish-speaking youth.

Parent-adolescent acceptance

Acceptance with mothers and fathers was rated by adolescents using an 8-item acceptance subscale of the Children’s Reports of the Parent Behavior Inventory measure (Schwarz, Barton-Henry, & Pruzinsky, 1985) at separate points in the interview. Adolescents evaluated acceptance with parents on a 5-point scale (1 = almost never to 5 = almost always) and the items were averaged. A sample item is, “My mother/father speaks to me in a warm and friendly voice.” In the present study, Cronbach’s alphas for English-speaking youth were .90 for youth and mothers and .93 for youth and fathers. Cronbach’s alphas for Spanish-speaking youth were .92 for youth and mothers and .85 for youth and fathers. Higher scores indicated greater acceptance.

Time spent with parents

Parent-adolescent shared time (i.e., time adolescents spent with both mothers and fathers) was collected during the series of seven nightly phone interviews. During phone interviews, adolescents reported on the durations (in minutes) and the companions (e.g., siblings, parents, peers) of 86 daily activities. The number of minutes that adolescents reported spending with mothers and fathers was aggregated across the seven nightly phone interviews to measure total time spent with mothers and fathers (regardless of the presence of others in the activities). Mothers’ and fathers’ time spent with adolescents was highly correlated (r = .72, p < .001); therefore, time spent with both parents was used. That is, the time spent with parents variable includes the proportion of time spent with both mothers and fathers (i.e., time spent with mothers and fathers divided by total time adolescents reported across the seven phone calls). Further, adolescents’ reports were used because they participated in all seven calls, whereas parents only participated in four calls. Correlations between adolescents’ and parents’ reports of time spent together for the 4 phone calls that both participated in were .86 for mothers and youth and .83 for fathers and youth. Eating meals and watching television were the most frequent activities for adolescents to engage in with both their mothers and fathers.

Results

Overview

The analyses are organized around the two study goals. First, we examine how adolescents’ cultural orientations/familism values were linked to Mexican-origin adolescents’ intentions to engage in sexual intercourse. Second, we investigate the moderating roles of mothers’ and fathers’ acceptance and time spent with parents on these associations, examine the moderating role of sex, and explore the 3-way interactions between cultural orientations/familism values, parent-adolescent relationship qualities, and adolescent sex in predicting sexual intentions. Initially, descriptive statistics and correlations for study variables were conducted to assess normality of the data, describe the sample, and examine bivariate relationships, separately for boys and girls (see Table 1). With regard to missing data, two adolescents did not have data on the sexual intentions variable and there was incomplete phone data for 12 adolescents (i.e., adolescent refused to participate in phone interviews); these adolescents were excluded from the analyses.

Table 1.

Correlations and Descriptive Statistics For All Study Variables Separately For Boys (Above Diagonal; n = 123) and Girls (Below Diagonal, n = 123).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | -- | .35* | −.04 | −.12 | −.46* | −.05 | −.10 | .03 |

| 2. Sexual intentions | .39* | -- | −.15 | −.19* | −.15 | −.07 | .19* | −.11 |

| 3. Maternal acceptance | −.07 | −.40* | -- | .45* | .03 | .17 | .04 | .27* |

| 4. Paternal acceptance | −.16 | −.17 | .53* | -- | .26* | .04 | .26* | .42* |

| 5. Parental time | −.39* | −.31* | .19* | .23* | -- | −.04 | .10 | .07 |

| 6. Anglo orientation | −.21* | .02 | .19* | .20* | −.04 | -- | −.33* | .04 |

| 7. Mexican orientation | −.05 | −.12 | .10 | .08 | .15 | −.48* | -- | .11 |

| 8. Familism values | −.13 | −.17 | .28* | .24* | .17 | .07 | .25* | -- |

|

| ||||||||

| M Girls Only | 15.81 | 1.63 | 4.00 | 3.54 | .15 | 3.87 | 3.83 | 4.24 |

| SD | 1.64 | .80 | .81 | 1.02 | .11 | .77 | .76 | .50 |

|

| ||||||||

| M Boys Only | 15.59 | 2.68 | 3.91 | 3.63 | .14 | 3.97 | 3.58 | 4.21 |

| SD | 1.44 | 1.14 | .78 | .96 | .11 | .65 | .77 | .69 |

Note. Parental time is a proportion score that was calculated as time with parents divided by total time reported in all activities to represent the percentage of girls’ and boys’ time spent with parents and to control for individual differences in the total amount of time reported (N = 116 for boys; N = 118 for girls).

p < .05.

Next, a series of hierarchical regressions were performed to analyze associations between adolescents’ cultural orientations and familism values and their sexual intentions. Regressions were run separately for Anglo orientation, Mexican orientation, and familism values and for each moderator (i.e., maternal acceptance, paternal acceptance, and time spent with parents) predicting youths’ sexual intentions. The models included four steps illustrated here with Anglo orientation and maternal acceptance as the predictor and moderator, respectively. In the first step of all models, age was entered as a control variable because older youth are more likely to be sexually active than younger youth (Guttmacher Institute, 2006). In the second step, main effects of adolescent sex, Anglo orientation, and maternal acceptance were included. In the third step, all 2-way interactions were entered (e.g., Adolescent sex × Anglo orientation, Adolescent sex × Maternal acceptance, Anglo orientation × Maternal acceptance) and in the fourth step, the 3-way interaction (e.g., Anglo orientation × Maternal acceptance × Adolescent sex) was included. Moderation was tested using procedures established by Baron and Kenny (1998). All variables were centered before being entered into regression equations and follow up tests were conducted for significant interactions according to procedures suggested by Aiken and West (1991). To correct the Type I error that may result from the number of regression models, a Šidàk-Bonferroni correction was made (Šidàk, 1967). This correction is a modification of the Bonferroni technique, but has less impact on statistical power (Keppel & Wickens, 2004). According to this correction, it was appropriate to use p < .05 as the significance level.

The regression analyses below are described in the following order: Anglo orientation, Mexican orientation, and familism values. Within each section, the regressions for mothers’ and fathers’ acceptance and time spent with parents are described separately.

Anglo Orientation

Parent-adolescent acceptance

In this model (see Table 2), sexual intentions were predicted from adolescents’ reports of their Anglo orientation and acceptance with mothers. The first step was significant, revealing that older adolescents reported greater intentions for sex than did younger adolescents. For the remaining regression models, the first step was always significant; therefore, the discussion of the models will begin with the second step. The second step, which included adolescent sex, Anglo orientation, and maternal acceptance, was significant. Boys reported greater sexual intentions than girls; this effect was significant in all of the regression analyses and will not be discussed in the remaining analyses. Contrary to our hypothesis, Anglo orientation was not positively associated with youths’ sexual intentions. Further, higher levels of maternal acceptance were associated with lower levels of sexual intentions. The third step in the model including the 2-way interactions did not account for a significant increase in the variance explained beyond the second step. The final step in the model, which included the 3-way interaction between adolescent sex, Anglo orientation, and maternal acceptance was significant and accounted for a significant increase in variance.

Table 2.

Hierarchical Regressions Predicting Youths’ Sexual Intentions from Anglo Orientation, Sex, and a Moderator.

| Moderators | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Maternal Acceptance (N = 244) | Paternal Acceptance (N = 244) | Time Spent with Parents (N = 232) | ||||

| β | SE β | β | SE β | β | SE β | |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Adolescent Age | .31* | .04 | .31* | .04 | .29* | .05 |

| F (1, 243) = 20.6, p < .01, R2 = .07 | F (1, 243) = 20.6, p < .01, R2 =.07 | F (1, 231) = 17.9, p < .01, R2 = .07 | ||||

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Anglo | .13 | .11 | .09 | .11 | .09 | .11 |

| Moderator | −.24* | .10 | −.09 | .09 | −.10 | .87 |

| Sex1 | .46* | .12 | .49* | .12 | .48* | .12 |

| F (4, 240) = 33.2, p < .01, R2 = .34 | F (4, 240) = 29.9, p < .01, R2 = .32 | F (4, 228) = 25.4, p < .01, R2 = .29 | ||||

| Step 3 | ||||||

| Anglo × Moderator | −.03 | .12 | −.03 | .12 | −.03 | .98 |

| Anglo × Sex | −.10 | .17 | −.10 | .17 | −.10 | .18 |

| Moderator × Sex | .09 | .15 | −.05 | .12 | .05 | 1.12 |

| F (7, 237) = 19.8, p < .01, R2 = .35 | F (7, 237) = 17.4, p < .01, R2 = .32 | F (7, 225) = 14.7, p < .01, R2 = .29 | ||||

| Step 4 | ||||||

| Anglo × Moderator × Sex | .15* | .20 | .04 | .18 | .02 | 1.50 |

| F (8, 236) = 18.3, p < .01, R2 = 36 | F (8, 236) = 15.3, p < .01, R2 = .32 | F (8, 224) = 12.8, p < .01, R2 = .29 | ||||

Note. The β weights are for each step in the analysis.

p < .05.

Boys = 1.

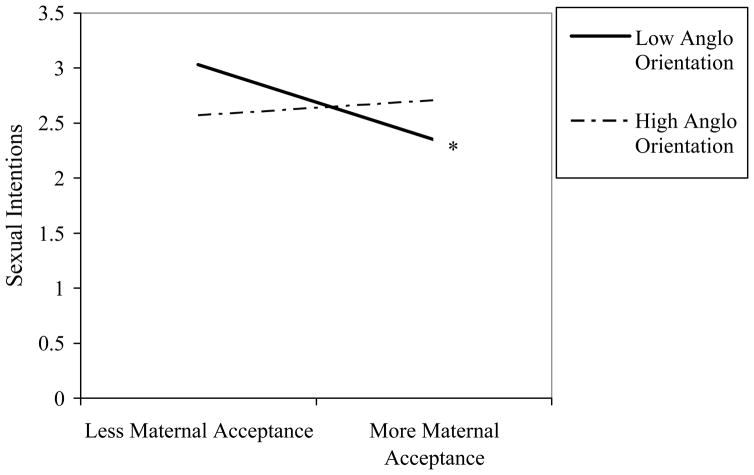

To follow-up on the significant 3-way interaction, interactions between Anglo orientation and maternal acceptance were conducted separately for boys and girls. When maternal acceptance was included as the moderator, the follow-up tests were not significant. However, when Anglo orientation was included as the moderator, follow-up tests revealed that there was a negative relationship between maternal acceptance and sexual intentions when boys reported less orientation to Anglo culture, t (120) = −2.54, p < .05, but not when boys reported more orientation to Anglo culture, t (120) = .49, ns (see Figure 1). Thus, boys who were less Anglo-oriented reported fewer intentions to have sex in the presence of acceptance from mothers. This finding did not support our hypothesis. The interaction was not significant for girls.

Figure 1.

Interaction between maternal acceptance and Anglo orientation predicting boys’ sexual intentions.

Turning to adolescents’ reports of fathers’ acceptance as a moderator (also show in Table 2), the second step in the model predicting sexual intentions from Anglo orientations and fathers’ acceptance was significant, with only adolescent sex as a significant predictor. Further, the 2-and 3-way interactions were not significant.

Time spent with parents

In the model predicting sexual intentions from Anglo orientation, adolescent sex, and time spent with parents, shared time was not a significant predictor and the 2- and 3-way interactions were not significant (see Table 2).

Mexican Orientation

Parent-adolescent acceptance

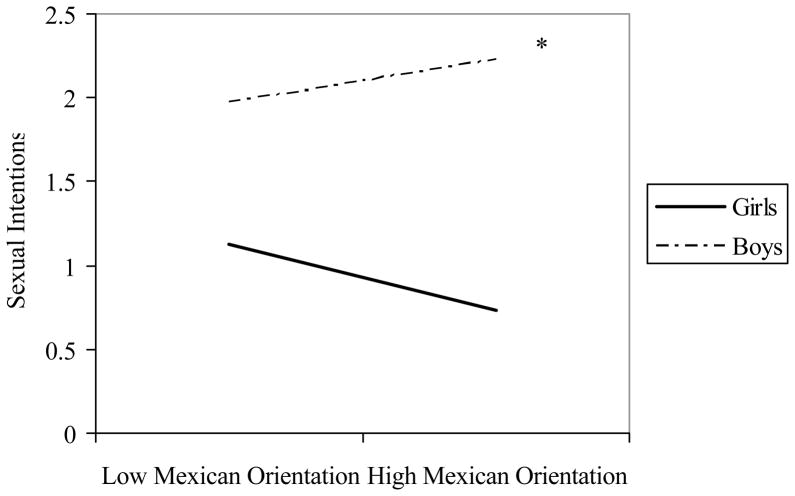

For acceptance with mothers (see Table 3), the second step in the model predicting sexual intentions from Mexican orientation and acceptance, was significant, revealing that mothers’ acceptance was negatively related to adolescents’ sexual intentions. Contrary to our hypothesis, Mexican orientation was not negatively related to youths’ intentions for sex. The third and fourth steps also were significant and accounted for a significant increase in variance. Supporting our hypothesis, there was a significant Mexican orientation × Adolescent sex × Maternal acceptance in the fourth step. Follow up t-tests revealed that for boys reporting high (but not low) maternal acceptance, there was a positive relation between Mexican orientation and sexual intentions, t (207) = 1.92, p = .06 (see Figure 2). Thus, for boys with high levels of acceptance from mothers, greater orientations to Mexican culture were associated with greater intentions for sex, compared to boys with low levels of acceptance from mothers. The slope for girls was not significant, t (207) = −1.23, ns.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Regressions Predicting Youths’ Sexual Intentions from Mexican Orientation, Sex, and a Moderator.

| Moderators | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Maternal Acceptance (N = 244) | Paternal Acceptance (N = 244) | Time Spent with Parents (N = 232) | ||||

| β | SE β | β | SE β | β | SE β | |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Adolescent Age | .31* | .04 | .30* | .04 | .29* | .04 |

| F (1, 243) = 20.6, p < .01, R2 = .07 | F (1, 243) = 20.6, p < .01, R2 =.07 | F (1, 231) = 17.9, p < .01, R2 = .07 | ||||

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Mexican | −.06 | .11 | −.06 | .11 | −.08 | .11 |

| Moderator | −.23* | .10 | −.09 | .08 | −.11 | .86 |

| Sex1 | .50* | .12 | .52* | .12 | .49* | .12 |

| F (4, 240) = 27.4, p < .01, R2 = .35 | F (4, 240) = 31.1, p < .01, R2 = .33 | F (4, 228) = 26.1, p < .01, R2 = .30 | ||||

| Step 3 | ||||||

| Mexican × Moderator | .08 | .14 | .14 | .11 | .07 | 1.14 |

| Mexican × Sex | .21* | .15 | .25* | .15 | .23* | .16 |

| Moderator × Sex | .01 | .15 | −.09 | .13 | .03 | 1.11 |

| F (7, 237) = 21.1, p < .01, R2 = .37 | F (7, 237) = 20.7, p < .01, R2 = .36 | F (7, 225) = 16.5, p < .01, R2 = .32 | ||||

| Step 4 | ||||||

| Mexican × Moderator × Sex | −.17* | .19 | −.08 | .15 | −.05 | 1.54 |

| F (8, 236) = 19.3, p < .01, R2 = 38 | F (8, 236) = 18.2, p < .01, R2 = .36 | F (8, 224) = 14.5, p < .01, R2 = .32 | ||||

Note. The β weights are for each step in the analysis.

p < .05.

Boys = 1.

Figure 2.

Interaction between Mexican orientation and adolescent sex predicting sexual intentions for youth reporting high acceptance with mothers.

For acceptance with fathers, the second step in the model was significant, with adolescent sex as a significant predictor (see Table 3). The third step was also significant, revealing a significant 2-way interaction between Mexican orientation and sex; however, follow-up t-tests were not significant. The 3-way interaction was not significant.

Time spent with parents

For time spent with parents, the second step in the model was significant, with only adolescent sex as a significant predictor (see Table 3). The third step in the model was significant, revealing a 2-way interaction between Mexican orientation and sex, but the follow-ups were not significant. The 3-way interaction was not significant.

Familism values

Parent-adolescent acceptance

The second step in the model for acceptance with mothers was significant (see Table 4), such that mother-adolescent acceptance was negatively related to sexual intentions. The 2- and 3-way interactions were not significant predictors.

Table 4.

Hierarchical Regressions Predicting Youths’ Sexual Intentions from Familism Values, Sex, and a Moderator.

| Moderators | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Maternal Acceptance (N = 244) | Paternal Acceptance (N = 244) | Time Spent with Parents (N = 232) | ||||

| β | SE β | β | SE β | β | SE β | |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Adolescent Age | .30* | .04 | .30* | .04 | .29* | .04 |

| F (1, 243) = 20.6, p < .01, R2 = .07 | F (1, 243) = 20.6, p < .01, R2 =.07 | F (1, 231) = 17.9, p < .01, R2 = .07 | ||||

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Familism | −.02 | .17 | −.07 | .18 | −.17 | .19 |

| Moderator | −.22* | .11 | −.06 | .09 | −.09 | .85 |

| Sex1 | .49* | .12 | .51* | .12 | .49* | .12 |

| F (4, 240) = 33.2, p < .01, R2 = .34 | F (4, 240) = 30.4, p < .01, R2 = .32 | F (4, 228) = 26.0, p < .01, R2 = .30 | ||||

| Step 3 | ||||||

| Familism × Moderator | .03 | .23 | .06 | .17 | .17 | 1.37 |

| Familism × Sex | −.05 | .22 | .00 | .22 | .09 | .23 |

| Moderator × Sex | .07 | .16 | −.07 | .13 | .04 | 1.11 |

| F (7, 237) = 19.0, p < .01, R2 = .34 | F (7, 237) = 17.3, p < .01, R2 = .32 | F (7, 225) = 14.7, p < .01, R2 = .29 | ||||

| Step 4 | ||||||

| Familism × Moderator × Sex | −.05 | .27 | −.10 | .20 | −.18* | 1.69 |

| F (8, 236) = 16.6, p < .01, R2 = 34 | F (8, 236) = 15.2, p < .01, R2 = .32 | F (8, 224) = 13.5, p < .01, R2 = .30 | ||||

Note. The β weights are for each step in the analysis.

p < .05.

Boys = 1.

In the model predicting sexual intentions from familism values and acceptance, the second step was significant for fathers, with only adolescent sex as a significant predictor. Additionally, contrary to our hypothesis, familism values were not negatively related to youths’ intentions for sex. The interactions did not explain additional variance.

Time spent with parents

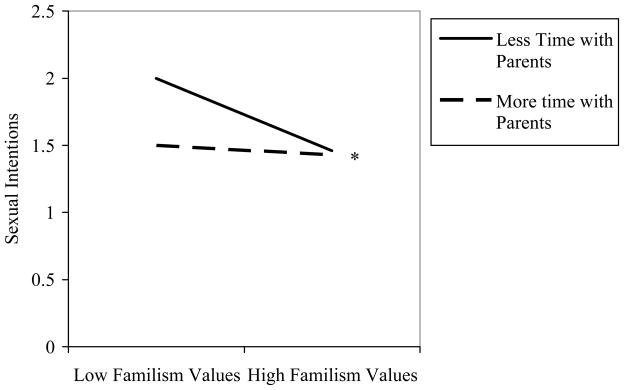

The second step predicting sexual intentions from adolescent sex, familism values, and time spent with parents was significant. The third and fourth steps also were significant. There was a significant 3-way interaction between familism values, adolescent sex, and time spent with parents (see Figure 3), such that there was a significant negative association between familism values and sexual intentions for girls who reported spending less time with parents, t (114) = −2.41, p < .05, as compared to girls who reported spending more time with parents t (114) = −.47, ns. Thus, for girls who were spending less time with parents, having greater familism values were associated with fewer intentions for sex compared to girls who were spending more time with parents. The interaction was not significant for boys.

Figure 3.

Interaction between familism values and time spent with parents predicting girls’ sexual intentions.

Discussion

In general, research on Latino youths’ sexuality is focused on risky sexual behaviors and little is known about Latino youths’ normative sexual development (Raffaelli & Iturbide, 2009). This study provides insights into Mexican-origin youths’ normative sexual development by investigating the associations among culture, family relationships, and youths’ sexual intentions. Emerging from this cross-sectional study was the complex story of the interconnections among culture, family, and sex in predicting adolescents’ intentions to engage in sexual intercourse. Supporting cultural-ecological, sexual scripting, and risk and resilience perspectives, there was an interaction between adolescents’ Anglo orientations, perceptions of maternal acceptance, and adolescent sex in predicting intentions for sex. For boys, but not girls, higher levels of maternal acceptance were associated with lower sexual intentions when boys reported low involvement in Anglo culture. That is, maternal acceptance was associated with fewer sexual intentions for boys when they were less involved in US culture, and when boys had stronger ties to US culture, maternal warmth was not related to boys’ intentions to engage in sexual intercourse.

This pattern was contrary to our hypotheses. One potential explanation pertains to the nature of the measure of Anglo orientation, which is based on behaviors and involvement in Anglo culture. This measure assesses the frequency of hanging out with Anglo peers, watching television in English, and listening to music in English. Given that greater levels of acculturation are linked to involvement in sexual activity (Ford & Norris, 1993; Gilliam et al., 2007), being less involved in or exposed to Anglo culture and having a supportive mother may be beneficial to boys in that they report lower intentions for sex. It may be that under conditions of less exposure to mainstream culture, boys benefit from a close and supportive relationship with their mothers. In addition to emphasizing the importance of cultural orientations, these findings underscore the importance of mothers’ role when examining youths’ sexual intentions as mothers are significant socializing agents in youths’ lives (Thornton, Chatters, Taylor, & Allen 1990). The findings from the current study highlight the importance of Mexican-origin mothers as influential figures in their young adolescents’ lives, especially their sons.

The relationships between youths’ Mexican orientation, maternal acceptance, and adolescent sex also were complex. In support of our hypothesis, under conditions of high maternal acceptance, boys who were more oriented to Mexican culture reported greater intentions for sex than boys who were less oriented to Mexican culture. Within Latino culture, the importance of boys’ masculinity is highlighted through the gendered sexual script of machísmo that emphasizes traditional gender roles for men (e.g., men who have many sex partners are more masculine) and informs how they should behave sexually (Faulkner, 2003). Given that values are most likely to be transmitted from parent to child in the context of emotionally close relationships (Christopher, 2001), mothers may be encouraging their sons to be more masculine when they report stronger ties to Mexican culture. The findings of this study emphasize the need to highlight gender and gendered sexual scripts in future studies of Latino families and youth sexuality.

Turning to familism values and shared time, although shared time did not directly predict adolescents’ sexual intentions, we found that for Mexican-origin girls, but not boys, there was a negative association between familism values and sexual intentions for girls who spent less time with parents. When girls spent less time with their mothers and fathers, it appeared that familism values were protective. Latina adolescents who emphasize the importance of the family are more likely to delay sexual initiation to protect their families (Villarruel, 1998), and it appears that when adolescents spend less time with their parents, familism values may be preventing them from engaging in sexual intercourse. When girls spend more time with their mothers and fathers, familism values do not play a large role in determining their sexual intentions. Because they are spending time with their parents, they may have fewer opportunities to socialize with the opposite sex and engage in risky behaviors, such as early sexual intercourse (e.g., Fortenberry et al., 2006).

Limitations, Contributions, and Directions for Future Research

There were several limitations to the current study that provided directions for future research. First, the data were cross-sectional. Future studies should be longitudinal to examine how the cultural context and family factors are related to youths’ sexual intentions over time, and how these intentions (both to engage in sex and to engage in safe sex) are related to later sexual behaviors, including safe sex behaviors. Second, only adolescent self-reports were used. Other reporters or observational data on the parent-adolescent relationship will contribute to the literature on youth sexuality by giving diverse perspectives of relationship experiences (Furman, Jones, Buhrmester, & Adler, 1989) and reducing shared method variance. Third, our sample included Mexican-origin youth from two-parent families. Given previous empirical findings linking family structure and youth sexual outcomes (Upchurch, Aneshensel, Sucoff, & Levy-Storms, 1999), investigating these associations in diverse family structures is crucial. Fourth, we do not know how many of the youth in the study were already sexually active. In future studies, it will be important to discriminate among sexually active and sexually inactive youth when investigating these associations. Fifth, future studies should include larger sample sizes to increase the power to detect significant associations. By including these aspects in future studies of sexuality with Mexican-origin youth, researchers will gain a better understanding of normative sexual development among this population.

The current study offers several contributions to the literature on adolescent sexuality. This was one of the few studies to examine Mexican-origin youth sexuality using an ethnic-homogeneous design. This work reveals the diversity within this Mexican-origin youth sample and highlights the significance of focusing on adolescent adjustment within a cultural context. The present investigation further extended work on the role of culture by measuring how adolescents’ cultural orientations and familism values were related to their sexuality. In addition, to our knowledge, this is the first study to quantitatively assess how youths’ familism values are related to their sexual intentions. Finally, given the unique roles of parents in youths’ lives (Crockett et al., 2007; Parke & Buriel, 1998), the associations among adolescents’ relationships with both mothers and fathers and their intentions to engage in sexual intercourse were investigated. The implications of our findings for HIV prevention are important. For instance, boys experiencing warm relationships with mothers and reporting a high orientation to Mexican culture may be particularly at risk. In these contexts, mothers may be encouraging their sons to be more masculine (e.g., have numerous sexual partners; Faulkner, 2003), and, as a result, their sons may be at risk for contracting sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV. Targeting HIV prevention efforts at youth who are particularly at risk may be important. Overall, our study revealed that adolescents’ relationships with parents served as both risk and protective factors. Understanding how family and cultural characteristics may pose different risks and benefits for girls versus boys is informative for future preventive interventions.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the families and youth who participated in this project, and to the following schools and districts who collaborated: Osborn, Mesa, and Gilbert school districts, Willis Junior High School, Supai and Ingleside Middle Schools, St. Catherine of Sienna, St. Gregory, St. Francis Xavier, St. Mary-Basha, and St. John Bosco. We thank Susan McHale, Ann Crouter, Mark Roosa, Nancy Gonzales, Roger Millsap, Ji-Yeon Kim, Jennifer Kennedy, Lorey Wheeler, Devon Hageman, Melissa Delgado, Emily Cansler and Lilly Shanahan, for their assistance in conducting this investigation and Sandra Simpkins and Adriana Umaña-Taylor for their comments on this paper. Funding was provided by NICHD grant R01HD39666 (Kimberly Updegraff, Principal Investigator, Ann C. Crouter and Susan M. McHale, co-principal investigators, Mark Roosa, Nancy Gonzales, and Roger Millsap, co-investigators) and the Cowden Fund to the School of Social and Family Dynamics at ASU.

Contributor Information

Sarah E. Killoren, Colorado State University

Kimberly A. Updegraff, Arizona State University

F. Scott Christopher, Arizona State University.

References

- Adam MB, McGuire JK, Walsh M, Basta J, LeCroy C. Acculturation as a predictor of onset of sexual intercourse among Hispanic and White teens. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159:261–265. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.3.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala J. Confianza, consejos, and contradictions: Gender and sexuality lessons between Latino adolescent daughters and their mothers. In: Denner J, Guzmán BL, editors. Latína girls: Voices of adolescent strength in the United States. New York, NY: New York University Press; 2006. pp. 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Azmitia A, Brown JR. Latino immigrant parents’ beliefs about the “path of life” of their adolescent children. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States: Current research and future directions. Westport, CT: Praeger Press; 2002. pp. 77–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bámaca MY, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Shin N, Alfaro EC. Latino adolescents’ perceptions of parenting behaviors and self-esteem: Examining the role of neighborhood risk. Family Relations. 2005;54:621–632. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Domenech-Rodriguez M. Latino families: Myths and realities. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States: Current research and future directions. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2002. pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance, Surveillance Summaries, June 6 2008. MMWR 2008. 2008;57(SS-4) [Google Scholar]

- Christopher FS. To dance the dance: A symbolic interactional exploration of premarital sexuality. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Crockett LJ, Brown J, Russell ST, Shen Y. The meaning of good parent-child relationships for Mexican American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17:639–668. [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC, Head MR, McHale SM, Tucker CJ. Family time and the psychosocial adjustment of adolescent siblings and their parents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:147–162. [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar I, Arnold B, Maldonado R. Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans -II: A Revision of the Original ARSMA Scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1995;17:275–304. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM, Savin-Williams RC. Adolescent sexuality. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology, Vol. 1: Individual bases of adolescent development. 3. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2009. pp. 479–523. [Google Scholar]

- East PL. Racial and ethnic differences in girls’ sexual, marital, and birth expectations. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:150–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East PL, Khoo ST, Reyes BT. Risk and protective factors predictive of adolescent pregnancy: A longitudinal, prospective study. Applied Developmental Science. 2006;10:188–199. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner SL. Good girl or flirt girl: Latinas’ definitions of sex and sexual relationships. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2003;25:174–200. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ford K, Norris AE. Urban Hispanic adolescents and young adults: Relationship of acculturation to sexual behavior. Journal of Sex Research. 1993;30:316–323. [Google Scholar]

- Fortenberry JD, Katz BP, Blythe MJ, Juliar BE, Tu W, Orr DP. Factors associated with time of day of sexual activity among adolescent women. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster SL, Martinez CR. Ethnicity: Conceptual and methodological issues in child clinical research. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1995;24:214–226. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Tseng V, Lam M. Attitudes toward family obligations among American adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European backgrounds. Child Development. 1999;70:1030–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Jones L, Buhrmester D, Alder T. Children’s, parents’ and observers’ perspectives on sibling relationships. In: Zukow PG, editor. Sibling interaction across cultures: Theoretical and methodological issues. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag Publishing; 1989. pp. 165–183. [Google Scholar]

- Gilliam ML, Berlin A, Kozloski M, Hernandez M, Grundy M. Interpersonal and personal factors influencing sexual debut among Mexican-American young women in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;41:495–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillmore MR, Archibald ME, Morrison DM, Wilsdon A, Wells EA, Hoppe MJ, Nahom D, Murowchick E. Teen sexual behavior: Applicability of the theory of reasoned action. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:885–897. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Knight GP, Morgan-Lopez A, Saenz D, Sirolli A. Acculturation and the mental health of Latino youths: An integration and critique of the literature. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States: Current research and future directions (pp 45–74) Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Graber JA, Brooks-Gunn J, Galen BR. Betwixt and between: Sexuality in the context of adolescent transitions. In: Jessor R, editor. New perspectives on adolescent risk behavior. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1998. pp. 270–316. [Google Scholar]

- Guttmacher Institute. Facts on American Teens’ Sexual and Reproductive Health. New York: Author; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Huerta-Franco R, Malacara JM. Factors associated with the sexual experiences of underprivileged Mexican American adolescents. Adolescence. 1999;34:389–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan CP, Napoles-Springer A, Steward SL, Perez-Stable E. Smoking acquisition among adolescents and young Latinas. The role of socioenvironmental and personal factors. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26:531–550. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppel G, Wickens TD. Design and analysis: A researcher’s handbook. 4. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Gonzales NA, Saenz DS, Bonds DD, Germán M, Deardorff J, Roosa MW, Updegraff KA. The Mexican American cultural values scale for adolescents and adults. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2010;30:444–481. doi: 10.1177/0272431609338178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longmore MA. Symbolic interactionism and the study of sexuality. Journal of Sex Research. 1998;35:44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Marín G, Marín BV. Research with Hispanic populations. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Best KM, Garmezy N. Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Development and Psychopathology. 1990;2:425–444. [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Crouter AC, Bartko WT. Traditional and egalitarian patterns of parental involvement: Antecedents, consequences, and temporal rhythms. In: Featherman D, Lerner R, Perlmutter M, editors. Life-span development and behavior, Vol. II. New York: Erlbaum; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. Changing demographics in the American population: Implications for research on minority children and adolescents. In: McLoyd VC, Steinberg L, editors. Studying minority adolescents: Conceptual, methodological, and theoretical issues. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1998. pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- National Vital Statistics Report. Revised Birth and Fertility Rates for the 1990’s and New Rates for Hispanic populations, 2000 and 2001: United States. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics; 2005. Retrieved September 10, 2005 from. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr51/nvsr51_12/.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbu JU. Origins of human competence: A cultural-ecological perspective. Child Development. 1981;52:413–429. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan LF, Meyer-Bahlburg HFL. African-American and Latina inner-city girls’ reports of romantic and sexual development. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2003;20:221–238. [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Buriel R. Socialization in the family: Ethnic and ecological perspectives. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. 3. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 463–552. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins DF, Villarruel FA. An ecological risk-factor examination of Latino adolescents’ engagement in sexual activity. In: Montero-Sieburth M, Villarruel FA, editors. Making invisible Latino adolescents visible (pp 83–106) New York, NY: Falmer Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli M, Iturbide MI. Sexuality and sexual risk taking behaviors among Latino adolescents and youth adults. In: Villarruel FA, Carlo G, Contreras Grau JM, Azmitia M, Cabrera NJ, Chahin TJ, editors. Handbook of US Latino psychology: Developmental and community based perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. pp. 399–413. [Google Scholar]

- Roosa MW, Morgan-Lopez AA, Cree WK, Specter MM. Ethnic culture, poverty, and context: Sources of influence on Latino families and children. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States: Current research and future directions. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2002. pp. 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan S, Franzetta K, Manlove J. Hispanic teen pregnancy and birth rates: Looking behind the numbers (Publication #2005-01) Child Trends Research Brief. 2005 Available at www.childtrends.org.

- Sabogal F, Marín G, Otero-Sabogal R, Vanoss Marín B, Perez-Stable EJ. Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn’t? Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9:397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz JC, Barton-Henry ML, Pruzinsky T. Assessing child-rearing behaviors: A comparison of ratings made by mother, father, child, and sibling on the CRPBI. Child Development. 1985;56:462–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šidàk Z. Rectangular confidence region for the means of multivariate normal distributions. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1967;62:626–633. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton MC, Chatters L, Taylor RJ, Allen W. Sociodemographic and environmental correlates to racial socialization by black parents. Child Development. 1990;61:401–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. The Hispanic population in the United States: 2000. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000. (PC Publication No. P25-535) [Google Scholar]

- Upchurch DM, Aneshensal CS, Mudgal J, McNeely CS. Sociocultural contexts of time to first sex among Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:1158–1169. [Google Scholar]

- Upchurch DM, Aneshensel CS, Sucoff CA, Levy-Storms L. Neighborhood and family contexts of adolescent sexual activity. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1999;61:920–933. [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, McHale SM, Whiteman SD, Thayer SM, Delgado MY. Adolescent sibling relationships in Mexican American families: Exploring the role of familism. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:512–522. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarruel AM. Cultural influences on the sexual attitudes, beliefs, and norms of young Latina adolescents. Journal of the Society of Pediatric Nurses. 1998;3:69–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.1998.tb00030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]