Abstract

Rationale

cAMP is an important regulator of myocardial function, and regulation of cAMP hydrolysis by cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases (PDEs) is a critical determinant of the amplitude, duration, and compartmentation of cAMP–mediated signaling. The role of different PDE isozymes, particularly PDE3A versus PDE3B, in the regulation of heart function remains unclear.

Objective

To determine the relative contribution of PDE3A versus PDE3B isozymes in the regulation of heart function and to dissect the molecular basis for this regulation.

Methods and Results

Compared to wild-type (WT) littermates, cardiac contractility and relaxation were enhanced in isolated hearts from PDE3A−/−, but not PDE3B−/−, mice. Furthermore, PDE3 inhibition had no effect on PDE3A−/− hearts but increased contractility in WT (as expected) and PDE3B−/− hearts to levels indistinguishable from PDE3A−/−. The enhanced contractility in PDE3A−/− hearts was associated with cAMP-dependent elevations in Ca2+ transient amplitudes and increased SR Ca2+ content, without changes in L-type Ca2+ currents (ICa,L) of cardiomyocytes, as well as with increased SR Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA2a) activity, SR Ca2+ uptake rates, and phospholamban (PLN) phosphorylation in SR fractions. Consistent with these observations, PDE3 activity was reduced ~8-fold in SR fractions from PDE3A−/− hearts. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments further revealed that PDE3A associates with both SERCA2a and PLN in a complex which also contains AKAP-18, PKA-RII and PP2A.

Conclusion

Our data support the conclusion that PDE3A is the primary PDE3 isozyme modulating basal contractility and SR Ca2+ content by regulating cAMP in microdomains containing macromolecular complexes of SERCA2a-PLN-PDE3A.

Keywords: cAMP, PDE3A Knock-out mice (PDE3A−/−), SERCA2a, calcium regulation, contractility

INTRODUCTION

Heart function is tightly regulated by the sympathetic-driven beta-adrenergic system, via alterations in the activity of cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA)1. The effects of PKA are finely tuned through AKAPs (A-kinase anchoring proteins) which recruit PKA into multi protein complexes containing many signaling molecules including 3′,5′-cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases (PDEs) and protein phosphatases, as well as end-effector molecules1, 2. PDEs are a unique class of enzymes responsible for the degradation of cAMP, the primary molecule regulating PKA. PDEs are divided into 11 gene families, with many of the 21 individual PDE genes producing multiple protein products via alternative mRNA splicing or utilization of different transcription initiation sites. Recent studies have established that PDEs assemble in an isoform-specific manner into specialized macromolecular complexes within discrete functional compartments, thereby allowing for precise spatiotemporal control of cAMP/PKA-signalling3, 4.

Murine hearts express genes from several PDE families. Although PDE8A was recently shown to regulate the acute actions of β-receptor stimulation5, PDE3 and PDE4 isoforms have traditionally been considered as the primary PDEs involved in regulation of cardiac contractility in mice and other species6. In murine myocardium both PDE3 and PDE4 activity regulate baseline Ca2+ transients and myocardial contractility by modulating cAMP/PKA-dependent SR Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA2a pump) activity in microdomains that do not contain ryanodine receptors or L-type Ca2+ channels7-9. Studies in humans have also established that PDE3 inhibitors markedly enhance myocardial contractility, relaxation, and diastolic function6, 10 which have been linked to β-receptor-dependent and cAMP/PKA-dependent increases in SR Ca2+ uptake11 via PKA-dependent phosphorylation of phospholamban (PLN)12, although β-receptor-dependent effects on L-type Ca2+ channels have also been reported in rats13. These observations are consistent with a model wherein cAMP compartmentalization and Ca2+ transients are regulated by PDE3 enzymes within microdomains containing SERCA2a as well as possibly other regulatory proteins2-4, 14. Although PDE3 inhibitors provide short-term benefit in heart transplant patients and end-stage heart failure patients, particularly when responses to β-adrenergic receptor agonists are lacking, chronic administration of PDE3 inhibitors increase mortality15, 16. Despite these cardiovascular side-effects, PDE3 inhibitors (such as cilostazol) are nevertheless used for treating intermittent claudication, a peripheral vascular disease17.

The molecular basis for the myocardial effects of PDE3 inhibitors remains unclear with different studies suggesting the major cardiac PDE3 isozyme is either PDE3A18 or PDE3B19. Since currently available PDE3 inhibitors do not discriminate between PDE3A and PDE3B, it has been challenging to dissect the relative roles for PDE3A or PDE3B in the myocardium. In this study, we used PDE3A−/− 20 and PDE3B−/−21 mice to better characterize the isoform-dependence for the regulation of myocardial contractility by PDE inhibitors. Our studies establish that PDE3A, not PDE3B, regulates baseline contractility in murine myocardium by cAMP-dependent modulation of Ca2+ transients, SR Ca2+ ATPase activity and PLN phosphorylation in SERCA2a-containing SR microdomains of ventricular cardiomyocytes.

METHODS

Animal

Age-matched (8~16 weeks old) WT and PDE3A−/− littermates on a C57BL6/J background20 were used for experiments in this report. For some experiments age-matched WT C57BL6 mice were purchased from Jackson labs. Protocols for mouse generation and maintenance were approved by the NHLBI Animal Care and Use Committee and the Canadian Council of Animal Care. The animal experimental protocols are in accordance with “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (NIH Publication, revised 1996, No.86-23).

Detailed methods for the experiments presented and discussed in this report are included in the Online Data Supplement at http://circres.ahajournals.org.

RESULTS

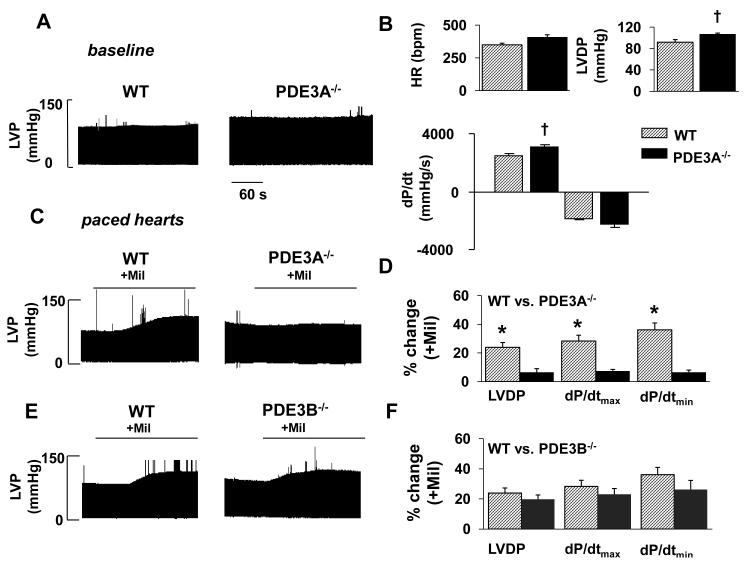

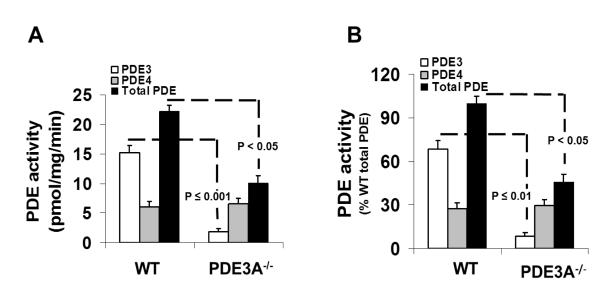

We started by measuring cardiac contractility in isolated ex vivo Langendorff hearts because PDE3 inhibition affects vascular resistance which complicates the assessment of intrinsic cardiac function in intact mice22, 23. As summarized in Figure 1 (A&B) and Online Table I, isolated hearts from PDE3A−/− mice showed elevated (p<0.05, n=5) left ventricular developed pressure (LVDP=106.5±2.6 mmHg) and contractility as assessed by the maximum (positive) time derivative of LVDP (+dP/dtmax=3080±193 mmHg/s) compared to WT (2499±101 mmHg/s). We next explored the effects of PDE3A inhibition on contractility. Because PDE3 inhibition elevates heart rate in WT mice6, which can influence contractility, we performed these studies on externally paced isolated hearts (via right atria) at rates (8Hz) that were slightly above the HRs observed (6.6±0.4Hz) after PDE3 inhibition. Treatment with 10μmol/L milrinone (Mil), which selectively inhibits both PDE3A and PDE3B22, had no effect on LVDP (P=0.71, n=5) or +dP/dtmax (P=0.55, n=5) in paced PDE3A−/− hearts, but increased (p<0.001, n=5) these parameters in WT hearts (Figure 1C,D Online Table I). Milrinone also had no effect on LVDP and +dP/dtmax in unpaced PDE3A−/− hearts. By contrast, LVDP and +dP/dtmax in PDE3B−/− hearts was indistinguishable from WT (P>0.477) before or after Mil treatment (Figure 1E,F). These functional studies support the conclusion that PDE3A is the primary PDE3 isozyme regulating baseline cardiac contractility. Consistent with this conclusion, Figure 2 shows that total PDE3 activity is ~8-fold lower in SR fractions from mice lacking PDE3A (i.e. 1.8±1.3 pmol/mg/min in PDE3A−/− SR fractions compared to 15.1±1.8 pmol/mg/min in WT) which is similar to results in heart homogenates20. Moreover, the absolute differences in specific PDE3 activity were indistinguishable (P=0.493) from the absolute differences in total PDE activity between these groups (10.1±1.2 pmol/mg/min in PDE3A−/− versus 22.5±1.1 pmol/mg/min in WT). While it is possible that the loss of PDE3A leads to compensatory changes in other PDE isoforms24, no changes in PDE4 activity (another major cardiac PDE in mice) were observed between PDE3A−/− and WT SR fractions (Figure 2).

Figure 1. PDE3A deficient hearts exhibit increased LVDP and dP/dtmax, but are not responsive to PDE3 inhibition with Milrinone.

A) Baseline left ventricular pressure measurements (after 20 min equilibration period) in WT and PDE3A−/− hearts. B) Mean data comparing baseline cardiac function between WT (n=5) and PDE3A−/− (n=5) hearts. C) Pressure recordings in paced WT and PDE3A-deficient hearts during milrinone (Mil) infusion. D) Cardiac function changes in paced WT (n=5) and PDE3A −/− (n=5) hearts induced by Mil. E) Pressure measurements in paced WT and PDE3B-deficient hearts during Mil infusion. F) Cardiac function changes in paced WT (n=3) and PDE3B −/− (n=3) hearts following milrinone treatment. Paced was introduced at frequencies that were just above the HRs achieved following Mil treatment (8Hz). HR = intrinsic heart rate, LVDP = left ventricular developed pressure, dP/dtmax = maximum rate of change of pressure development and dP/dtmin = min rate of change of pressure development. *P<0.05 vs. baseline conditions, †P<0.05 vs. WT control.

Figure 2. Total PDE and PDE3 activities are decreased in SR microsomes isolated from PDE3A−/− hearts.

PDE activity in WT and PDE3A−/− cardiac SR fractions, expressed as (A) specific activity (pmol cAMP hydrolyzed/min/mg) or (B) a percentage of the total PDE activity in WT hearts. Total PDE activity was determined in 3 independent SR microsomal preparations using cilostamide to inhibit PDE3, rolipram to inhibit PDE4 and IBMX to inhibit total PDE activity. *p<0.001 vs WT, **p<0.05 vs WT total PDE activity.

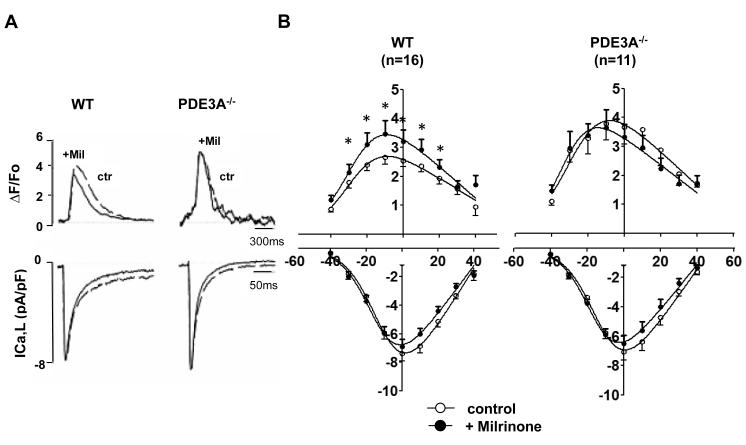

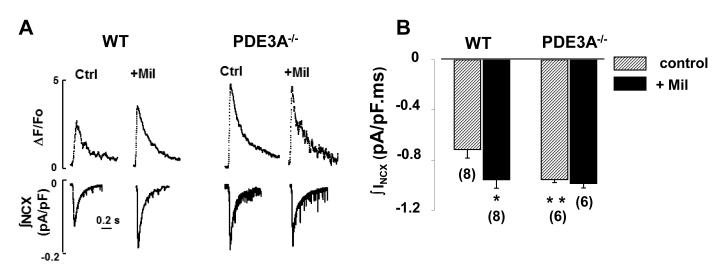

To determine the cellular mechanisms mediating the effects of PDE3A on cardiac contractility, we simultaneously recoded Ca2+transients and L-type Ca2+channel currents (ICa,L) in isolated cardiomyocytes. Consistent with our isolated heart studies, Figure 3 and Online Table II establish that Ca2+ transients (ΔF/FO=3.6 ± 0.6) were elevated in PDE3A−/− cardiomyocytes (P<0.05) along with trends towards faster (P=0.08) decay (τ=142±4.4 ms, n =9) compared to WT (ΔF/FO=2.5±0.2 and τ=158±9.7 ms, n=16). By contrast, ICa,L properties (maximal conductance (Gmax), the half-maximal activation voltage (V1/2), or inactivation kinetics of ICa,L) did not differ between PDE3A−/− and WT cardiomyocytes (Online Table II) even after maximal activation of cAMP/PKA25 using a combination of 100nmol/L isoproterenol plus 100μmol/L IBMX (Online Figure I). Increased Ca2+ transients without ICa,L alterations in the PDE3A−/− cardiomyocytes were observed at all voltages (Figure 3), demonstrating that PDE3A ablation enhances excitation-contraction coupling efficiency26 at all voltages (Online Figure II). Importantly, Mil increased (P<0.001, n=16) Ca2+ transients and accelerated (P=0.026, n=16) their decay in WT, but not in PDE3A−/−, cardiomyocytes (P=0.219, n=9), without effecting ICa,L in either group (Figure 3B, Online Table II). A definitive role for cAMP in the differences between WT and PDE3A−/− cardiomyocytes was established by dialyzing myocytes with the selective cAMP antogonist, Rp-cAMPS, which had no affect (p=0.117, n=7) on Ca2+ transients in WT cardiomyocytes, but reduced the amplitudes (P<0.001, n=7) and prolonged the relaxation times (P<0.05, n=7) of Ca2+ transients in PDE3A−/− cardiomyocytes to the levels indistinguishable from the amplitudes (p=0.151) and relaxation times (P=0.635) in WT cardiomyocytes, with or without Rp-cAMPS dialysis (Online Figure III, Online Table II). To establish whether the cAMP-dependent elevations in Ca2+ transients originated from altered SR Ca2+ levels, we measured time-integrated Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) currents (∫INCX) and [Ca2+]i (ΔF/FO) in response to rapid perfusion with 20 mmol/L caffeine, as done previously27. Both ∫INCX and [Ca2+]i were increased (p<0.001, n=6) in PDE3A−/− cardiomyocytes compared to WT (Figure 4, Online Table II). Furthermore, Mil had no effect (P=0.284, n=6) on SR Ca2+ content in PDE3A−/− cardiomyocytes while increasing (P<0.05, n=8) SR Ca2+ content in WT (i.e. from −0.71± 0.07 to −0.96 ± 0.07 pA/pF), to the same levels (P=0.49, n=6) measured in PDE3A−/− cells.

Figure 3. Effects of PDE3A ablation on Ca2+ transients and ICaL.

A) Raw traces of simultaneous Ca2+ transients (top) and ICa,L (bottom) measured at 0mV. The holding potential was −85 mV and a 200 millisecond depolarization ramp to −45mV was added before the depolarization step to 0 mV. The measurements were made 8 minutes after membrane rupture to permit full equilibration of the Fluo-3 dye. Either milrinone (Mil) or vehicle (Ctrl) was added for an additional 8 minutes before measurements of ICaL and Ca2+ transients were made. B) Mean data illustrating effects of PDE3A ablation on Ca2+ transient amplitudes (top) and ICaL densities (bottom) in WT (n=16) and PDE3A−/− (n=9) cardiomyocytes with protocols as in Panel A, except depolarizations were varied from –40mV to +30mV (see Online Methods). *p<0.05 versus control in same group; †p<0.05 between groups.

Figure 4. PDE3A ablation increases SR Ca2+ content and SERCA2a function.

A) Representative traces depicting Ca2+ release from the SR (transients at the top) and accompanying INCX (bottom) induced by application of 20mmol/L caffeine to WT and PDE3A−/− cardiomyocytes, and then following perfusion with 10 μmol/L milrinone. B) Average data illustrating the effects of PDE3 inhibition with 10μmol/L milrinone (+Mil) or PDE3A ablation on SR Ca2+ content as gauged by integrating INCX (n-values indicated). *p<0.05 versus WT control.

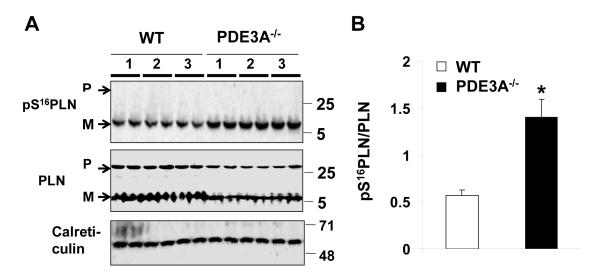

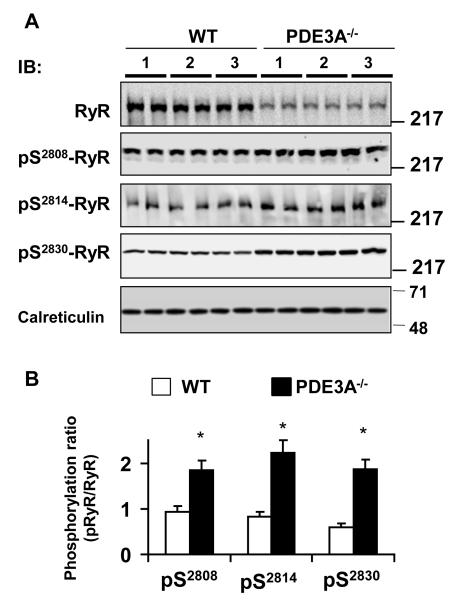

To identify the potential downstream molecular targets mediating the cAMP-dependent changes in Ca2+ homeostasis of myocardium from PDE3A−/− mice, we measured phospholamban (PLN) and SR Ca2+ release channel (RyR2) phosphorylation levels. As seen in Figure 5, PLN phosphorylation at the PKA-dependent site, Ser-16, was elevated 2.1- fold (P<0.001, n=3) in PDE3A−/− myocardium compared to WT, without differences (P=0.940; Online Figure IV) in PLN phosphorylation at Thr-17, the Ca2+-calmodulin kinase II (CaMKII)-dependent site. RyR2 phosphorylation was also elevated (P<0.01) at both PKA-dependent site (Ser-2808 and Ser-2030) as well as the CaMKII-dependent site (Ser-2814) in PDE3A−/− myocardium compared to WT (Figure 6). PDE3A−/− hearts also showed elevated phosphorylation levels of several other PKA targets including the cAMP-dependent transcriptional factor, CREB, which could underlie the changes in SERCA2a and RyR2 expression seen in PDE3A−/− myocardium28 (Online Figure V).

Figure 5. Increased levels of PKA dependent phosphorylation of phospholamban in PDE3A−/− hearts.

Western blots of WT and PDE3−/− heart lysates (40 μg), illustrating the effect of PDE3A ablation on phosphorylation of PLN at PKA-dependent site Serine 16 (S16). A) PDE3A ablation increased phosphorylation of PLN (pPLN), with respect to total PLN at residue serine 16. Calreticulin was used as indicator of equal loading conditions. B) Bar graph summarizing p Ser16PLN/PLNtotal ratios in WT and PDE3A −/− hearts; ~2 fold increase in PDE3−/− lysates,*p< 0.01 versus WT (n=3 independent experiments, each with duplicate samples from 3 WT and 3 PDE3−/− heart lysates). In some experiments as a result of the protein samples heating, PLN run on a SDS-PAGE gel in its monomeric (5kDa) and pentameric forms (25kDa). Total PLN was used for the analyses.

Figure 6. Increased levels of PKA and CaMKII dependent phosphorylation of SR Ca2+ release channels in PDE3A−/− hearts.

A) Western blots of WT and PDE3−/− heart lysates (50 μg/lane), illustrating the effect of PDE3A ablation on phosphorylation of SR Ca2+ release channel (RyR2) at PKA-dependent sites Serine 2808(pS2808, Abcam 59225), Serine 2030 (pS230, Badrilla A010-32) and CaMKII dependent site serine 2814 (pS2814, Badrilla A010-31). Calreticulin was used to confirm equal loading between the samples. B) Bar graph summarizing pRyR2/RyR2 ratios in WT and PDE3A−/− hearts. ~2 fold increase in PDE3−/− lysates at all three sites.*p< 0.01 versus WT (n=2 independent experiments, each with duplicate samples from 3 WT and 3 PDE3−/− heart lysates).

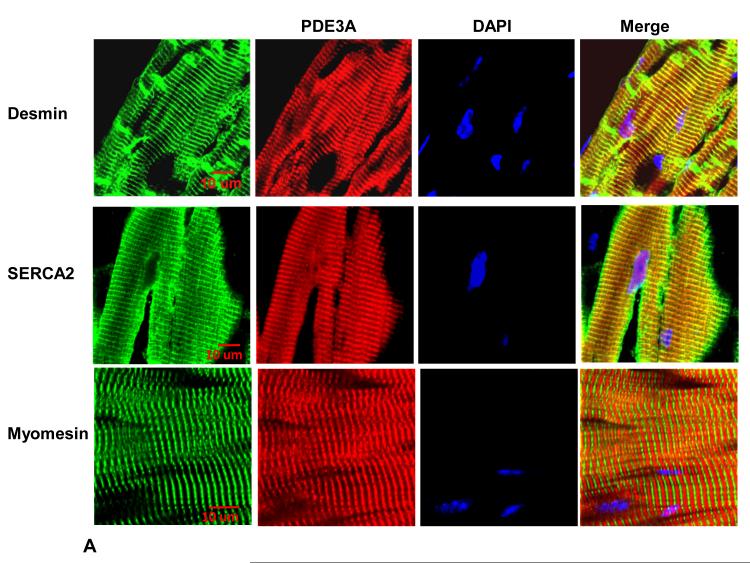

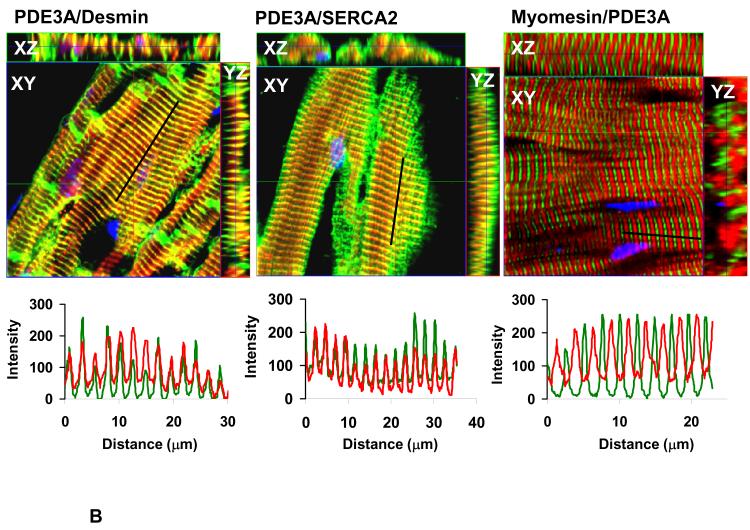

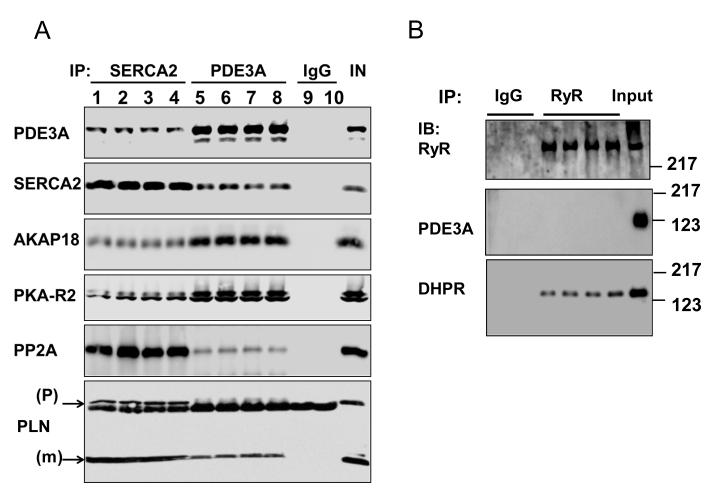

Since PKA-dependent modulation of SR Ca2+ uptake requires SERCA2a/PLN/AKAP18 molecular complexes14, we investigated whether PDE3A might also be part of this complex. Figure 7 established that PDE3A colocalizes with SERCA2a, and Figure 8 demonstrates that PDE3A interacts with SERCA2a, phospholamban, AKAP-18, PKA-RII and PP2A but not with RyR2. The presence of PDE3A and SERCA2a in these immunoprecipitates was verified by LC-MS\MS analysis (Online Figure VI). Interactions between these proteins were also detected using discontinuous sucrose gradient centrifugation studies of WT mouse cardiac membranes (Online Figure VII), which showed that PDE3A, SERCA2a, and phospholamban co-fractionate.

Figure 7. PDE3A belongs to the SERCA2a/PLN macromolecular complex.

A) As described in methods, WT hearts (frozen sections) were incubated with rabbit anti-PDE3A-CT, anti desmin, anti-SERCA2, and anti-myomesin primary antibodies, followed by alexafluor® 488- or 594-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies, and imaged with Zeis LSM510 laser scanning confocal microscopy. Green stains for desmin (Z-lines) or SERCA2 while PDE3A is red and nuclei are blue (DAPI). Bar=10μm. B) Merged images from stack of 6-8 sections (with 1μm intervals) reveal co-localization of PDE3A, with desmin and SERCA2 but not with myomesin (labeling M-line green). X–Y (center), above X–Z (top) and Y–Z (right) planes are at indicated positions.

Figure 8. PDE3A co-immunoprecipitates with SERCA2 in murine cardiac tissue.

A) Representative Western blots from 2 way co-immunoprecipitation experiments, illustrating that PDE3A interacts with SERCA2a, PLN, PKA-RII and AKAP-18. As described in methods, precleared total WT heart lysates (1 mg) were incubated with anti-PDE3A (C terminal epitope) (3 μg) and anti-SERCA2a (3 μg) antibodies overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with protein G beads (2h, 4°C). Immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted from the beads, and subjected to SDS PAGE/Western immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. This experiment was representative of 3 independent experiments, (1heart/lane). B) Representative Western blots illustrating that PDE3A does not co-immunoprecipitate with the SR Ca2+ release channel (RyR2). Again, as described above, precleared total heart WT lysates (1mg) were incubated with anti-RyR antibodies, and immunuprecipitated proteins were subjected to SDS PAGE/Western immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. This experiment was representative of 2 independent experiments, (1heart/lane).

Taken together, our findings support the conclusion that PDE3A regulates excitation-contraction coupling, Ca2+ transients and contractility under basal conditions by modulating cAMP levels and PLN phosphorylation in SR microdomains containing the SR Ca2+ ATPase complexed with its regulatory partners. However, since CREB phosphorylation is also increased in PDE3A−/− hearts, it is conceivable that changes in the expression levels of Ca2+ handling proteins might also contribute to the functional alterations observed in PDE3A−/− mice. Indeed, as summarized in Online Figure V, the expression of SERCA2a was increased in PDE3A−/− myocardium compared to WT, which was associated with increases (P<0.05) in both the maximal rate (Vmax) of SERCA2a activity (56.8 ± 3.4 nmol Pi/mg/min) and the Ca2+ uptake rates (170.5 ± 9 nmol Ca2+/mg/3min) in SR vesicles isolated from PDE3A−/− myocardium compared to WT (33.05 ± 4.5 nmol Pi/mg/min and 81 ± 3.7 nmol Ca2+/mg/3min). Note that no differences (P=0.568) in Ca2+ sensitivity (Km) of the SERCA2a activity was observed between the groups between the groups, which is expected when cAMP is absent29 (Online Figure V). At first glance, SERCA2a elevations seem inconsistent with the observation that Ca2+ transients in the PDE3A−/− cardiomyocytes are normalized to WT levels by Rp-cAMPS dialysis. However, RyR2 expression levels was also markedly reduced in the PDE3A−/− myocardium (Online Figure V), which is predicted to reduce SR Ca2+ release, despite the elevated SR Ca2+ load, in PDE3A−/− cardiomyocytes.

DISCUSSION

It has been long established that PDE3 plays an important role in regulating intracellular cAMP levels and myocardial contractility in human hearts6, 10, 16. Accordingly, PDE3 inhibitors have been assessed in clinical trials for the treatment of heart failure. Unfortunately, chronic inhibition of PDE3 increases the incidence of ventricular arrhythmias and mortality15. Consequently, PDE3 inhibitors are only used to provide short-term inotropic support in conjunction with β-adrenergic blockers30, 31 in acutely decompensating cardiac patients. Although some previous studies have suggested that PDE3A is the predominant PDE3 isozyme expressed in the myocardium32, and is important in regulating myocardial function10, 16, 33, PDE3B has also been reported to be a major regulator of murine myocardial contractility via its association with PI3Kγ19.

Our studies establish that PDE3A is the isoform responsible for mediating the positive inotropic effects associated with the acute inhibition of PDE3s. Specifically, the loss of PDE3A (but not PDE3B) increases baseline myocardial contractility and eliminates the positive iontropic effects of milrinone in isolated Langendorff hearts. These effects of PDE3A ablation on cardiac contractility were associated with cAMP-dependent elevations of Ca2+ transients without affecting L-type Ca2+ channels, thereby leading to enhancements in the excitation-contraction coupling (ECC) gain. Although many factors could contribute to elevated Ca2+ cycling following PDE3A ablation, we found that PDE3A−/− myocardium had increased SR Ca2+ loading (measured via Ca2+ transients and integrated INCX in response to caffeine), which is a major regulator of ECC gain26. Moreover, milrinone had no effect in PDE3A−/− myocytes but elevated Ca2+ transients and SR Ca2+ load (but not ICa,L) in WT myocytes, establishing that PDE3A underlies the PDE-dependent changes in baseline cardiac contractility, Ca2+ transients and SR Ca2+ load.

The increased Ca2+ transients andSR Ca2+ loading in the PDE3A−/− myocardium occurred in association with enhanced SERCA activity (increased Vmax) and Ca2+uptake rates, elevated PLN phosphorylation levels (at the PKA-dependent site, S-16), increased SERCA2a expression levels, elevated RyR2 phosphorylation34 and reduced RyR2 expression. The changes in PLN and RyR2 phosphorylation suggest, as expected from compartmentation of PDE activity35, 36, that PDE3A regulates cAMP locally in subcellular SR regions of cardiomyocytes, thereby controlling both PLN and RyR2 phosphorylation. Our co-immunoprecipitation studies further demonstrate that PDE3A associates with SERCA2a and PLN as well as several other proteins previously reported to assemble into macromolecular complex with SERCA2a, including the PKA regulatory subunit (PKA-RII), the A-kinase anchoring protein (AKAP18 or AKAP 15/18δ), and protein phosphatase PP2A14. Remarkably, despite the increased RyR2 phosphorylation in PDE3A−/− myocardium, associations between PDE3A and RyR2 were not detected, suggesting the regulation of cAMP levels by PDE3A at the levels of SERCA2a may have “spillover effects” in the vicinity of RyR2 channels24, 37. Moreover, we also have found in human myocardial SR fractions that PDE3 inhibition increased the effects of cAMP on Ca2+ uptake, and that PDE3A co-immunoprecipitated with SERCA2a, PLN, AKAP18,PKA-RII, and PP2A (Ahmad, F. et al., unpublished observations). Collectively these results support the conclusion that PDE3A regulates cAMP levels within a microdomain of the SR containing a macromolecular complex comprised of SR Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA2a) and its major regulatory partners14.

Although the link between the changes in heart function and the cAMP-dependent increases in basal SR Ca2+-ATPase activity induced by the loss of PDE3A is straightforward, the functional consequences of increased RyR2 phosphorylation and reduced RyR2 expression are less obvious. Single channel studies have established that RyR2 phosphorylation by PKA (and by CaM II kinase) increases RyR2 channel open probability which, in principle, could have competing effects on Ca2+ transients and contractility27, 38. Specifically, increased RyR2 channel open probabilities can not only lead to enhanced SR Ca2+ transients but also causes elevated Ca2+ leak which can deplete SR Ca2+ stores, thereby reducing Ca2+ transients39. Since the loss of PDE3A was associated with elevated SR Ca2+ loads, it is reasonable to conclude that RyR2 phosphorylation did not lead to excessive Ca2+ leak which is consistent with the absence either of increased Ca2+ sparks in PDE3A−/−cardiomyocytes or of cardiac dysfunction in PDE3A−/−mice up to 6 months of age (data not shown). These observations support the conclusion that elevated RyR2 phosphorylation associated with PDE3A ablation contributes to the increased Ca2+ transients and cardiac contractility by enhancing RyR2 openings and SR Ca2+ release. Enhanced RyR2 openings can also help explain the rather modest acceleration of Ca2+ transient relaxation rates in PDE3A−/− cardiomyocytes, despite large elevations in SERCA2a activity. Specifically, enhanced RyR2 opening could lead to prolonged SR Ca2+ release thereby counteracting the enhanced relaxation expected with accelerated SR Ca2+ uptake by SERCA2a27. Interestingly, although the phosphorylation levels of RyR2 channels were increased, RyR2 protein expression was reduced in PDE3A−/− myocardium, which is expected to reduce SR Ca2+ release. These changes in RyR2 expression might represent a compensatory response to limit the extent of Ca2+ transient elevations and these changes could be mediated by the increases in CREB phosphorylation. Clearly, more studies are warranted to more fully assess the consequences of altered RyR2 phosphorylation and RyR2 expression on Ca2+ homeostasis when PDE3 activity is inhibited. Examining the effects of PDE3 inhibition or PDE3A ablation in myocardium lacking either PLN or SERCA2a could be helpful in dissecting the relative consequences of PLN-SERCA2a versus other molecular targets in mediating the functional consequences of PDE3/PDE3A inhibition.

Previous clinical investigations have established that chronic treatment of heart failure patients with PDE3 inhibitors is associated with increased mortality. Consequently, these agents are contraindicated in the chronic treatment of cardiac patients15. Although the mechanism for the increased mortality seen in cardiac patients treated with PDE3 inhibitors is likely complex in model systems, chronic inhibition of PDE3 activity induces sustained elevations in the expression of the transcription repressor ICER, which is linked to increased cardiomyocyte apoptosis, via an autoregulatory positive-feedback loop40,41. These studies suggest that PDE3A−/− hearts might show long-term deterioration of cardiac function. However, despite evidence of the increased CREB phosphorylation typical of AngII- and ISO-induced HF, both hearts and isolated cardiomyocytes from PDE3A−/− mice showed enhanced cardiac function. Thus, it would appear that depletion of PDE3A alone is insufficient to induce cardiac dysfunction in mice under normal physiologic conditions and additional cardiac stresses or further ageing are necessary to observe the detrimental effects of the loss of PDE3A function.

In PDE3A−/− mice, the absence of effects of milrinone on heart and myocyte function, at doses that are expected to selectively inhibit both PDE3A and PDE3B activities 22, establishes that PDE3B plays a minor role in the regulation of basal heart function. Although these observations are consistent with previous studies concluding that PDE3B activity in the heart is associated with non-myocardial cells such as vascular smooth muscle cells, fibroblasts, adipocytes and blood cells32, 33, 42, another study suggested that PDE3B is present in cardiomyocytes, where it regulates myocardial cAMP levels and serves to acutely protect the heart following biomechanical stress19. If PDE3B activity is important primarily under conditions of cardiac stress, then the toxicity observed in the failed clinical trials using milrinone might be related predominantly to PDE3B inhibition, making it plausible that a selective PDE3A inhibitor might be a useful strategy for providing positive inotropic activity to heart failure patients. Clearly more studies will be required to dissect the relative roles of PDE3A versus PDE3B in normal and diseased myocardium.

Our results demonstrate that the loss of PDE3A leads to adaptive changes in the myocardial protein expression levels (SERCA2a, RyR2) possibly via CREB activation. However, these changes in expression do not fully explain the functional changes observed between PDE3A−/− and WT hearts. Indeed, pressure, Ca2+ transients, and SR Ca2+ levels in the myocardium of WT mice were elevated by PDE3 inhibitors to the levels seen in PDE3A−/− mice while these parameters were only affected by inhibition of PKA with Rp-cAMPS in cardiomyocytes from PDE3A−/− mice. It is conceivable that these differences between the groups could be related to compensatory changes in expression or activity of other PDE isozymes43. However, we found that the activity of PDE4, the other major murine cardiac PDE isozyme24, 37, 44, which also regulates Ca2+ transients and myocardial contractility9, was unaffected by PDE3A ablation.

In summary, we demonstrated that PDE3A is the major PDE3 isozyme involved in the regulation of baseline myocardial contractile function by modulating PKA-dependent PLN phosphorylation and thus both SR Ca2+ loads and Ca2+ transients, without affecting L-type Ca2+ currents. This regulation by PDE3A occurs via selective regulation of cAMP levels in SR microdomains containing macromolecular complexes comprising PDE3A plus other constituents of the SR Ca2+ ATPase complex (including SERCA2a, PLN, PKA, PP2A and AKAP18). Since PDE3B may be essential and protective in response to cardiac stress19, it is conceivable that selective inhibition of PDE3A might be a useful strategy for reversing the reduced contractile function observed in heart disease, although their use may be limited by proarrhythmic effects associated with RyR2 phosphorylation38, 39.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What is Known?

Phosphodiesterases (PDEs) catalyze the breakdown of cAMP and are thereby critical regulators of cardiac function.

Many different PDE isozymes are present in heart and their individual function remains unclear

What New information Does this Article Provide?

PDE3A, but not PE3B, regulates baseline myocardial contractility by controlling the level of phospholamban phosphorylation and Ca2+ ATPase activity in microdomains of the sarcoplasmic reticulum

PDEs are critical determinants of cAMP–dependent signaling in myocardium. The role of different PDE isozymes, particularly PDE3A versus PDE3B, in regulating heart function remains unknown. We found that hearts from mice lacking PDE3A (PDE3A−/−), but not PDE3B, have elevated cardiac contractility and were unresponsive to pharmacologic PDE3 inhibition. The enhanced contractility in PDE3A−/− hearts was associated with cAMP-dependent elevations in Ca2+ transient amplitudes and SR Ca2+ content, without changes in L-type Ca2+ current (ICa,L). The loss of PDE3A eliminated >85% of the PDE3 activity and increased phospholamban (PLN) phosphorylation and SR Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA2a) activity as well as ryanodine receptor (RyR2) phosphorylation. PDE3A was found to associate with SERCA2a, PLN, AKAP-18, PKA-RII and PP2A in a macromolecular complex. These findings establish that PDE3A is the primary PDE3 isozyme modulating basal cardiac contractility and SR Ca2+ content by regulating cAMP in microdomains containing macromolecular complexes of SERCA2a-PLN-PDE3A. Since PDE3B may protect against cardiac stress, selective inhibition of PDE3A might be a useful therapeutic strategy for correcting the impaired contractility observed in heart disease, although this approach may be limited by proarrhythmic effects associated with RyR2 phosphorylation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank Dr. Matthew Movsesian (Utah) for his helpful discussions. We also acknowledge the professional skills and advice from Dr. Zu-Xi Yu (Patholgy Core Facility, NHLBI), and Dr Christian Combs and Dr. Daniela Malide (Microscopy Core Facility, NHLBI).

SOURCES OF FUNDING This work was supported by grants from Canadian Institutes of Health Research PHB (MOP-62954). VM, FA, JS, SH, YWC, and EM were supported by the NHLBI Intramural Research Program. PHB is a Career Investigator with the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario. SB held a postdoctoral fellowship from the Heart and Stroke Richard Lewar Centre of Excellence (HSRLCE), University of Toronto.

Non-standard Abbreviations

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine triphosphate

- PDE3A

Phosphodiesterase type 3A

- PKA

cAMP-dependent protein kinase type A

- AKAP

A-Kinase Anchoring Protein

- MIL

milrinone, PDE3 family specific phosphodiesterase inhibitor

- SERCA2a

sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase type 2a

- RyR2

cardiac ryanodine receptor

- PLN

phospholamban

- pPLN

phosphorylated phospholamban

- ICaL

L-type calcium current

- LVP

left ventricular pressure

- LVDP

left ventricular developed pressure

- EDP

end diastolic pressure

- dP/dtmax

first positive derivative of the maximum pressure development

- dP/dtmin

first negative derivative of the maximum pressure development

- TAC

trans-aortic constriction

- pCREB

phosphorlyated CREB

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES None

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bers DM. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 2002;415:198–205. doi: 10.1038/415198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michel JJ, Scott JD. Akap mediated signal transduction. Annu.Rev.Pharmacol.Toxicol. 2002;42:235–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.083101.135801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinberg SF, Brunton LL. Compartmentation of g protein-coupled signaling pathways in cardiac myocytes. Annu.Rev.Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:751–773. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaccolo M, Movsesian MA. Camp and cgmp signaling cross-talk: Role of phosphodiesterases and implications for cardiac pathophysiology. Circ.Res. 2007;100:1569–1578. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.106.144501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patrucco E, Albergine MS, Santana LF, Beavo JA. Phosphodiesterase 8a (pde8a) regulates excitation-contraction coupling in ventricular myocytes. J.Mol.Cell Cardiol. 2010;49:330–333. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osadchii OE. Myocardial phosphodiesterases and regulation of cardiac contractility in health and cardiac disease. Cardiovasc.Drugs Ther. 2007;21:171–194. doi: 10.1007/s10557-007-6014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerfant BG, Gidrewicz D, Sun H, Oudit GY, Penninger JM, Backx PH. Cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release and load are enhanced by subcellular camp elevations in pi3kgamma-deficient mice. Circ.Res. 2005;96:1079–1086. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000168066.06333.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kerfant BG, Rose RA, Sun H, Backx PH. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma regulates cardiac contractility by locally controlling cyclic adenosine monophosphate levels. Trends Cardiovasc.Med. 2006;16:250–256. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerfant BG, Zhao D, Lorenzen-Schmidt I, Wilson LS, Cai S, Chen SR, Maurice DH, Backx PH. Pi3kgamma is required for pde4, not pde3, activity in subcellular microdomains containing the sarcoplasmic reticular calcium atpase in cardiomyocytes. Circ.Res. 2007;101:400–408. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.156422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colucci WS. Cardiovascular effects of milrinone. Am Heart J. 1991;121:1945–1947. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(91)90829-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yano M, Kohno M, Ohkusa T, Mochizuki M, Yamada J, Hisaoka T, Ono K, Tanigawa T, Kobayashi S, Matsuzaki M. Effect of milrinone on left ventricular relaxation and ca(2+) uptake function of cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Am.J.Physiol Heart Circ.Physiol. 2000;279:H1898–H1905. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.4.H1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacLennan DH, Kranias EG. Phospholamban: A crucial regulator of cardiac contractility. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:566–577. doi: 10.1038/nrm1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rochais F, Abi-Gerges A, Horner K, Lefebvre F, Cooper DM, Conti M, Fischmeister R, Vandecasteele G. A specific pattern of phosphodiesterases controls the camp signals generated by different gs-coupled receptors in adult rat ventricular myocytes. Circ.Res. 2006;98:1081–1088. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000218493.09370.8e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lygren B, Carlson CR, Santamaria K, Lissandron V, McSorley T, Litzenberg J, Lorenz D, Wiesner B, Rosenthal W, Zaccolo M, Tasken K, Klussmann E. Akap complex regulates ca2+ re-uptake into heart sarcoplasmic reticulum. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:1061–1067. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Packer M, Carver JR, Rodeheffer RJ, Ivanhoe RJ, DiBianco R, Zeldis SM, Hendrix GH, Bommer WJ, Elkayam U, Kukin ML. Effect of oral milrinone on mortality in severe chronic heart failure. The promise study research group. N.Engl.J Med. 1991;325:1468–1475. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199111213252103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Movsesian M, Stehlik J, Vandeput F, Bristow MR. Phosphodiesterase inhibition in heart failure. Heart Fail.Rev. 2009;14:255–263. doi: 10.1007/s10741-008-9130-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mangiafico RA, Fiore CE. Current management of intermittent claudication: The role of pharmacological and nonpharmacological symptom-directed therapies. Curr.Vasc.Pharmacol. 2009;7:394–413. doi: 10.2174/157016109788340668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun B, Li H, Shakur Y, Hensley J, Hockman S, Kambayashi J, Manganiello VC, Liu Y. Role of phosphodiesterase type 3a and 3b in regulating platelet and cardiac function using subtype-selective knockout mice. Cell Signal. 2007;19:1765–1771. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patrucco E, Notte A, Barberis L, Selvetella G, Maffei A, Brancaccio M, Marengo S, Russo G, Azzolino O, Rybalkin SD, Silengo L, Altruda F, Wetzker R, Wymann MP, Lembo G, Hirsch E. Pi3kgamma modulates the cardiac response to chronic pressure overload by distinct kinase-dependent and -independent effects. Cell. 2004;118:375–387. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masciarelli S, Horner K, Liu C, Park SH, Hinckley M, Hockman S, Nedachi T, Jin C, Conti M, Manganiello V. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase 3a-deficient mice as a model of female infertility. J.Clin.Invest. 2004;114:196–205. doi: 10.1172/JCI21804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi YH, Park S, Hockman S, Zmuda-Trzebiatowska E, Svennelid F, Haluzik M, Gavrilova O, Ahmad F, Pepin L, Napolitano M, Taira M, Sundler F, Stenson Holst L, Degerman E, Manganiello VC. Alterations in regulation of energy homeostasis in cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase 3b-null mice. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3240–3251. doi: 10.1172/JCI24867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sutherland FJ, Shattock MJ, Baker KE, Hearse DJ. Mouse isolated perfused heart: Characteristics and cautions. Clin.Exp.Pharmacol.Physiol. 2003;30:867–878. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2003.03925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Endoh M, Hori M. Acute heart failure: Inotropic agents and their clinical uses. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2006;7:2179–2202. doi: 10.1517/14656566.7.16.2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Houslay MD, Adams DR. Pde4 camp phosphodiesterases: Modular enzymes that orchestrate signalling cross-talk, desensitization and compartmentalization. Biochem.J. 2003;370:1–18. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Arcangelis V, Soto D, Xiang Y. Phosphodiesterase 4 and phosphatase 2a differentially regulate camp/protein kinase a signaling for cardiac myocyte contraction under stimulation of beta1 adrenergic receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:1453–1462. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.049718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ginsburg KS, Bers DM. Modulation of excitation-contraction coupling by isoproterenol in cardiomyocytes with controlled sr ca2+ load and ca2+ current trigger. J Physiol. 2004;556:463–480. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.055384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sah R, Ramirez RJ, Backx PH. Modulation of ca(2+) release in cardiac myocytes by changes in repolarization rate: Role of phase-1 action potential repolarization in excitation-contraction coupling. Circ.Res. 2002;90:165–173. doi: 10.1161/hh0202.103315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayr B, Montminy M. Transcriptional regulation by the phosphorylation-dependent factor creb. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:599–609. doi: 10.1038/35085068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wuytack F, Raeymaekers L, Missiaen L. Molecular physiology of the serca and spca pumps. Cell Calcium. 2002;32:279–305. doi: 10.1016/s0143416002001847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lowes BD, Simon MA, Tsvetkova TO, Bristow MR. Inotropes in the beta-blocker era. Clin.Cardiol. 2000;23:III11–III16. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960231504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shakar SF, Abraham WT, Gilbert EM, Robertson AD, Lowes BD, Zisman LS, Ferguson DA, Bristow MR. Combined oral positive inotropic and beta-blocker therapy for treatment of refractory class iv heart failure. J.Am.Coll.Cardiol. 1998;31:1336–1340. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reinhardt RR, Chin E, Zhou J, Taira M, Murata T, Manganiello VC, Bondy CA. Distinctive anatomical patterns of gene expression for cgmp-inhibited cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases. J.Clin.Invest. 1995;95:1528–1538. doi: 10.1172/JCI117825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maurice DH, Palmer D, Tilley DG, Dunkerley HA, Netherton SJ, Raymond DR, Elbatarny HS, Jimmo SL. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase activity, expression, and targeting in cells of the cardiovascular system. Mol.Pharmacol. 2003;64:533–546. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.3.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bridge JH, Savio-Galimberti E. What are the consequences of phosphorylation and hyperphosphorylation of ryanodine receptors in normal and failing heart? Circ Res. 2008;102:995–997. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.176172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Georget M, Mateo P, Vandecasteele G, Lipskaia L, Defer N, Hanoune J, Hoerter J, Lugnier C, Fischmeister R. Cyclic amp compartmentation due to increased camp-phosphodiesterase activity in transgenic mice with a cardiac-directed expression of the human adenylyl cyclasetype 8 (ac8) FASEB J. 2003;17:1380–1391. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0784com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mongillo M, McSorley T, Evellin S, Sood A, Lissandron V, Terrin A, Huston E, Hannawacker A, Lohse MJ, Pozzan T, Houslay MD, Zaccolo M. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based analysis of camp dynamics in live neonatal rat cardiac myocytes reveals distinct functions of compartmentalized phosphodiesterases. Circ.Res. 2004;95:67–75. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000134629.84732.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Houslay MD. Underpinning compartmentalised camp signalling through targeted camp breakdown. Trends Biochem.Sci. 2010;35:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shan J, Betzenhauser MJ, Kushnir A, Reiken S, Meli AC, Wronska A, Dura M, Chen BX, Marks AR. Role of chronic ryanodine receptor phosphorylation in heart failure and beta-adrenergic receptor blockade in mice. J.Clin.Invest. 2010;120:4375–4387. doi: 10.1172/JCI37649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lehnart SE, Wehrens XH, Reiken S, Warrier S, Belevych AE, Harvey RD, Richter W, Jin SL, Conti M, Marks AR. Phosphodiesterase 4d deficiency in the ryanodine-receptor complex promotes heart failure and arrhythmias. Cell. 2005;123:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yan C, Miller CL, Abe J. Regulation of phosphodiesterase 3 and inducible camp early repressor in the heart. Circulation Research. 2007;100:489–501. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000258451.44949.d7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yan C, Ding B, Shishido T, Woo CH, Itoh S, Jeon KI, Liu W, Xu H, McClain C, Molina CA, Blaxall BC, Abe J. Activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 reduces cardiac apoptosis and dysfunction via inhibition of a phosphodiesterase 3a/inducible camp early repressor feedback loop. Circ.Res. 2007;100:510–519. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000259045.49371.9c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Omori K, Kotera J. Overview of pdes and their regulation. Circ.Res. 2007;100:309–327. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000256354.95791.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pokreisz P, Vandenwijngaert S, Bito V, Van den Bergh A, Lenaerts I, Busch C, Marsboom G, Gheysens O, Vermeersch P, Biesmans L, Liu X, Gillijns H, Pellens M, Van Lommel A, Buys E, Schoonjans L, Vanhaecke J, Verbeken E, Sipido K, Herijgers P, Bloch KD, Janssens SP. Ventricular phosphodiesterase-5 expression is increased in patients with advanced heart failure and contributes to adverse ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction in mice. Circulation. 2009;119:408–416. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.822072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller CL, Yan C. Targeting cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase in the heart: Therapeutic implications. J.Cardiovasc.Transl.Res. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s12265-010-9203-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.