Abstract

This study used an observational measure to examine how individual children’s engagement with teachers, peers, and tasks was associated with gains in self-regulation. A sample of 341 preschoolers was observed and direct assessments and teacher reports of self- regulation were obtained in the fall and spring of the preschool year.

Research Findings

Children’s positive engagement with teachers was related to gains in compliance/executive function and children’s active engagement with tasks was associated with gains in emotion regulation across the year. Engaging positively with teachers or peers was especially supportive of children’s gains in task orientation and reductions in dysregulation.

Practice & Policy

Results are discussed in relation to Vygotsky’s developmental theory, emphasizing that psychological processes are developed in the context of socially embedded interactions. Systematically observing how a child interacts with peers, teachers, and learning tasks in the preschool classroom holds potential to inform the creation of professional development aimed at supporting teachers in fostering individual children’s development within the early education environment.

The gap in early learning skills between children at-risk for school failure and their more advantaged peers widens over time and occurs for a variety of reasons (Jacobson-Chernoff, Flanagan, McPhee, & Park, 2007; Johnson, 2002; National Center for Education Science [NCES], 2000). Early self-regulation processes differ significantly between children and are a critical component of school readiness (Blair, 2002; McClelland, Morrison, & Holmes, 2000). Expanding our understanding of factors that account for differences in children’s self-regulation is essential for designing effective interventions to help close the school readiness gap (Anthony, Lonigan, Driscoll, Phillips, & Burgess, 2003; Crosnoe, Leventhal, Wirth, Pierce, & Pianta, 2010; Martin, Ryan, & Brooks-Gunn, 2010). Over the last ten years, there has been a marked increase in research defining, measuring, and exploring the mechanisms through which self-regulation develops (e.g., Eisenhower, Baker, & Blacher, 2007; Rimm-Kaufman, Curby, Grimm, Nathanson, & Brock, 2009). The purpose of this study was to examine how children’s engagement with teachers, peers, and tasks in preschool classrooms is related to their development of self-regulation.

Development of Self-Regulation

Disagreement exists over the definition of self-regulation, but it can be conceptualized as one’s own ability to focus attention, manage emotions, and control behaviors to cope effectively with environmental demands (Baumeister & Vohs, 2004; Blair & Razza, 2007; Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2009; Calkins & Williford, 2009). Children at this age dramatically increase their abilities to attend to activities, manage emotions, comply with adult demands and directives, delay engagement in specific activities, and engage in goal-directed behavior (Campbell & von Stauffenberg, 2008; Kuczynski & Kochanska, 1995). The preschool period is marked by both substantial development of as well as increasing expectations for children’s self-regulation, particularly in the areas of emotion, behavior, and cognition.

Emotion regulation

Emotion regulation processes refer to skills and strategies that serve to manage, modulate, inhibit, and enhance emotional arousal in a way that supports adaptive social and non-social responses (Calkins, 1997; Kopp 1989; Thompson, 1994). Children’s emotion regulation includes both external aids (e.g., comforting gestures from another) and internal strategies for managing emotional stimulation (Thompson & Lagattuta, 2006). Considerable research on emotion regulation demonstrates that successful regulation of affect influences children’s functioning in behavioral, academic, and social domains (Blair, Denham, Kochanoff, Blair Peters, & Granger; 2004; & Whipple, 2004; Eisenberg, Fabes, Nyman, Bernzweig, & Pinuelas, 1994; Thompson, 1994). Thus, children’s emotion regulation has been shown to be critical in supporting children’s development of social-emotional skills.

Behavior regulation

Behavior regulation is the ability to manage or control one’s own behavior, including compliance to adult demands and directives, the ability to control impulsive responses, delay engagement in specific activities, and monitor one’s own behavior (Kopp, 1982; Kuczynski & Kochanska, 1995). The ability to regulate one’s behavior (e.g., sit quietly and listen to a story, walk instead of run inside) predicts higher academic skills (e.g., emergent literacy, vocabulary, math) within the preschool year (McClelland et al., 2007; Miller, Gouley, Seifer, Disckstein, & Sheilds, 2004), and through second grade (McClelland, Acock, & Morrison, 2006). In contrast, children who are persistently emotionally and behaviorally dysregulated receive less instruction from teachers and have fewer opportunities to interact with peers (McClelland & Morrison, 2003). Research also suggests a link between children’s early behavioral regulation and later behavioral competence and social skills (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2000; Howse, Calkins, Anastopoulos, Keane, & Shelton, 2003). Overall, research suggests that behavioral regulation plays an important role in the development of children’s academic and behavioral competence.

Cognitive regulation

Cognitive regulation, often called cognitive control or executive functioning, encompasses a number of cognitive factors including working memory (the ability to mentally hold and manipulate information) and inhibitory control (the ability to resist the temptation to do something). Executive functioning involves the use of planfulness, control, reflection, competence, and independence when completing tasks (Paris & Newman, 1990). The ability to focus and attend to an activity or task (i.e., evidence good inhibitory control and attention) in preschool has been linked with higher kindergarten achievement (Blair & Razza, 2007). Further, effortful control of attention has been linked to socially appropriate behavior in the context of emotionally challenging situations (Kieras, Tobin, Graziano, & Rothbart, 2005).

Thus, children’s self-regulation of emotion, behavior, and cognition have been repeatedly linked to their concurrent and future functioning in social and academic domains (e.g., Alloway et al., 2005; Blair, Denham, Kochanoff, & Whipple, 2004; Eisenberg et al., 2000; Eisenburg, Valiente, & Eggum; 2010; Howse, Calkins, Anastopoulos, Keane, & Shelton, 2003; Kochanska, et al, 2000). However, children vary in the degree to which they enter kindergarten with adequate self-regulation skills (Rimm-Kaufman, Pianta, & Cox, 2000; Zhou, Hofer, Eisenberg, Reiser, Spinrad, & Fabes, 2007), and some children are at particular risk of starting school with poor self-regulation. Children from low-income families, compared with their more advantaged peers, are significantly more likely to have lower behavioral regulation in pre-kindergarten and kindergarten (Evans & Rosenbaum, 2008; Mistry, Benner, Biesanz, Clark, & Howes, 2010). This may be due to the fact that disadvantaged children may have fewer opportunities to interact with materials and tasks, and in social contexts with teachers and peers, in ways that allow them to practice their regulatory skills (Sektnam et al., 2010).

Hispanic children are disproportionately likely to come from low-income families (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008), and concerns have been raised about their school readiness (Galindo & Fuller, 2010). Research suggests that Hispanic children from low-income families may be particularly at-risk for disparities in social competence. Two recent studies suggest that Hispanic children from low-income families display lower levels of behavioral regulation than their middle income counterparts (Galindo & Fuller, 2010; Wanless, McClelland, Tominey, & Acock, 2011).

However, not all at-risk children have difficulty with self-regulation. Children who experience multiple social and environmental risks can have positive developmental outcomes despite the challenges that they face (Doll & Lyon, 1998). The early childhood classroom presents an environment that holds promise for encouraging self-regulation abilities in children that will enhance their success in later years (Blair & Diamond, 2008). In the present study, we examined the links between the quality of children’s engagement within the early childhood classroom and their development of self-regulation skills during preschool.

Self-Regulation within the Early Classroom Environment

The benefits of experiencing high quality interactions with teachers, peers, and learning tasks in preschool settings are well documented: children who experience higher quality interactions show greater academic and social development in preschool, particularly for children from home environments with multiple social and environmental risks (e.g., Burchinal, Peisner-Feinberg, Bryant & Clifford, 2000; Mashburn et al., 2008). Although much of research examining the association between young children’s interactions with teachers and peers and their development of self-regulation has hypothesized that self-regulation predicts children’s quality of interactions (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2010; Rudasill, 2011), there is an emerging body of literature that documents the importance of the classroom context in fostering the development of children’s self-regulation (e.g., Eisenhower et al., 2007; Noble, Norman, & Farah; 2005; Raver et al., 2010). For example, classroom quality in the fall of kindergarten has been linked to children’s greater self-control and work habits in the spring of kindergarten (Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2009). However, individual children within the same preschool classroom may have disparate preschool experiences (Pintrich et al., 1994; Shearer et al., 2008). For example, children within a single classroom may be differentially exposed to high quality interactions with their teacher (e.g., Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Howes, 2000). These individual experiences predict school adjustment over and above the general quality of the classroom’s relational environment (Birch & Ladd, 1997). The majority of children spend substantial time in preschool prior to kindergarten entry (Adams, Tout, & Zaslow, 2007), so a better understanding of how these early classroom experiences either facilitate or impede the development of children’s self-regulation is warranted.

Children’s ability to regulate their own behavior, emotions, and thinking varies according the demands of and available supports within the preschool classroom. Yet too little is known about the processes that facilitate the development of young children’s self-regulatory skills in the early childhood education environment. Children’s engagement with teachers, peers, and tasks in the classroom may be one factor associated with the development of self-regulatory skills.

The Development of Self-Regulation within Context

Vygotsky’s developmental theory stresses that psychological processes such as self-regulation are developed through interactions with adults, peers, and the learning context (Stetsenko & Vianne, 2009) and so provides a guiding framework to explore how the preschool classroom can support children’s development. Children develop self-regulating abilities as they engage in informal interactions with peers and adults (Vygotsky, 1978). Before children are able to self-regulate their behaviors, they gain control through “other-regulation” where their behavior is guided by others as they learn to initiate desired behaviors and refrain from negative behaviors (Bodrova & Leong, 2006). Development and learning do not only occur through access to high quality learning materials, but it is the use of the materials or curriculum in the context of a meaningful social interchange between the child and his or her teachers and/or peers that is necessary (Morrison et al., 2010). Below we summarize the research supporting specific links between children’s engagement with teachers, peers, and tasks in the early childhood education setting and development of self-regulation.

Children’s positive and supportive relationships with their teachers are associated with children’s academic, social-emotional, and self-regulation development (e.g., Birch & Ladd, 1997; Pianta, 1999; Trentacosta & Izard, 2007). When teachers describe their relationships with children as warm and close, young children show better emotion regulation skills (Shields et al., 2001), more social competence, and fewer problem behaviors (Mashburn et al., 2008). Conversely, teacher-child interactions characterized by high negativity, disagreement, and/or conflict are associated with lower levels of children’s self-directedness and cooperative participation in the classroom (Birch & Ladd, 1997). Thus, when children interact with teachers who establish positive emotional bonds with and meet the behavioral and regulatory needs of their students, this creates an environment that should be especially supportive for children’s ability to self-regulate. Although relationships between children and teachers are bi-directional with both teacher and child characteristics influencing the quality of the relationship (Birch & Ladd, 1998), there is growing empirical evidence suggesting that the quality of the teacher-child relationship longitudinally predicts children’s behavior (e.g., Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Meehan, Hughes, & Cavell, 2003; Pianta & Stuhlman, 2004). For example, researchers found that after controlling for children’s initial problem behaviors, teacher-child relationship quality significantly predicted children’s later social-emotional adjustment. Although the magnitude of the effects of teacher-child relationships on children’s outcomes is greater for concurrent ratings of relational quality (Pianta, Nimetz, & Bennett, 1997; Pianta & Stuhlman, 2004), research suggests that teacher-child relationship quality is predictive of longitudinal outcomes.

The importance of relationships for developing regulation skills and gaining social-emotional competence extends to the peer network. Children who have positive peer relationships characterized by sharing, appropriate communication, play, and acceptance are more likely to be successful at school (Downer & Pianta, 2006; Ladd & Burgess, 2001). Vygotsky (1978) theorized that play, specifically make-believe play, was particularly important for the development of self-regulation, as children have the opportunity to practice being regulated by, and also regulating peers’ as well as their own behavior. Emerging research supports this theory and suggests that classroom interactions with peers during play are associated with children’s self-regulation (e.g., Elias & Berk, 2002; Mendez, Fantuzzo, & Cicchetti, 2001). For example, Fantuzzo, Sekino, and Cohen (2004) found that children who exhibited low levels of disruptive play behaviors had higher levels of emotion regulation, whereas disruptive and disconnected peer play behaviors were associated with negative emotional and behavioral adjustment. Similarly, Elias & Berk (2002) observed three- and four-year-olds in the classrooms and found that complex socio-dramatic play predicted increases in on-task behavior. Children’s engagement with classroom task and activities is another aspect of the classroom context that can support their development of behavior regulation.

Positive task engagement is characterized by children’s enthusiastic, self-directed, and active involvement with classroom activities (Downer, Booren, Lima, Luckner, & Pianta, 2010; Fantuzzo, Perry, & McDermott, 2004). Children’s ability to participate and persist in classroom activities and learning tasks has been linked to the development of school readiness skills (Hughes & Kwok, 2006; McClelland et al., 2007; McClelland et al., 2000). Studies suggest that preschool children’s positive engagement with tasks and activities is associated with better attention and impulse control (Bierman, Torres, Domitrovich, Welsh, & Gest, 2009; Chang & Burns, 2005). Further, it has been suggested that interest and engagement in an activity strengthens inhibitory and attentional control during the activity (Pessoa, 2009). However, as Vygotsky’s theory emphasizes, children do not engage in classroom tasks and activities in isolation of their social relationships.

Birch and Ladd (1996, 1997) assert that children’s relationships with teachers and peers can serve as either supports or stressors that may facilitate or impede children’s classroom adaptation and participation. As outlined above, positive engagement with teachers and peers serve as a support to children and are associated with the development of self-regulation. Vygotsky theorizes that the optimal development of self-regulation occurs within a context where children are regularly provided with relational resources (e.g., positive relationships with teachers and peers), combined with stimulating classroom activities and tasks and activities (Bodrova & Leong, 2003). Thus, a Vygotskian perspective and the supportive research suggest that children must engage in both social exchanges and learning tasks and activities for psychological processes such as self-regulation to develop most optimally. In the current study, we explicitly examine the moderation of children’s engagement with peers and teachers with their engagement in tasks and activities to predict gains in self-regulation during the preschool year.

The Present Study

Recently, scholars have cited the need for research on how proximal classroom processes are associated with children’s self-regulation (Sektnam et al., 2010). Engagement with teachers, peers, and tasks have all been shown to facilitate or impede the development of young children’s regulation. However, we found no published research that concurrently examines these aspects of classroom engagement to identify their relative independent contributions to children’s self-regulation, and further, how aspects of engagement interact to influence children’s regulation skills. Furthermore, studies often use observational tools that have been designed to measure overall classroom quality (e.g., Caregiver Interaction Scale, Arnett, 1989; ECERS-R, Harms, Clifford, & Cryer, 2005; CLASS, Pianta, LaParo, & Hamre, 2008), rather than using measures that assess individual children’s experiences within the classroom context (e.g., the Emerging Academic Snapshot, Ritchie, Howes, Kraft-Sayre, & Weiser, 2001 and the ASPI, Shearer et al., 2008). Composite ratings of teachers’ engagement may miss important aspects of an individual child’s experiences within the classroom. The current study used a validated observation tool to capture individual children’s engagement with teachers, peers, and learning tasks and activities in the classroom.

Finally, this sample includes a large proportion of low-income Hispanic children (67%), a group who has been understudied, particularly with respect to classroom interactions and their social-emotional development. Limited research suggests that Hispanic children from low-income families may be more likely to experience low levels of behavioral regulation and social competence (Galindo & Fuller, 2010; Wanless et al., 2011). However, research also suggests that high-quality interactions with teachers, peers, and tasks, can benefit Dual Language Learners’ academic and social-emotional development (Castro, Páez, Dickinson, & Frede, 2011; Downer, López, Grimm, Hamagami, Pianta, & Howes, in press; Goldenberg, 2008). The largely Hispanic sample allows us to better understand the processes underlying the development of behavioral regulation for this growing population of children.

In a predominantly low-income Hispanic sample, we examined whether children’s engagement with teachers, peers, and tasks was linked with gains in their self-regulatory behaviors from fall to spring. We expected that children’s positive engagement with teachers, positive engagement with peers, and active engagement with classroom tasks and activities would be associated with greater gains in their self-regulation skills during preschool. We hypothesized that children who were more positively engaged with teachers or more positively engaged with peers and who were also more positively engaged with classroom tasks and activities would evidence the greatest gains in self-regulation during the preschool period. Additionally, we expected that the negative association of being less actively engaged with classroom tasks and activities on children gains in self-regulation would be minimized for children who tended to be positively engaged with teachers or peers.

Method

Participants

Participants were 341 preschool children enrolled in 100 preschool classrooms located in a large urban region in the southwestern United States. In terms of recruitment, permission was first secured from center directors, followed by full informed consent obtained from participating teachers. All parents in the classrooms were invited to participate and given an informed consent form and short family demographic survey, which they completed and returned to their child’s preschool teacher. The consent rate per classroom ranged from 8% to 100% (M = 37%, n = 667). From the children with parental consent, four children (two boys and two girls when possible) in each classroom were randomly selected to participate (consented children were ordered alphabetically according to last name and a random number generator list was used to select children). Because the goal of the larger study was to examine classroom engagement in a sample of typically developing preschoolers, children were excluded from selection if parents indicated that their child had an existing active Individualized Education Plan in the fall of the preschool year (5% of consented children). The average child age was 46.9 months (SD = 6.6 months). Fifty percent of the children were female, 67% were Hispanic. English was spoken in the majority of homes (61%), but Spanish was also a commonly used home language (65%). The sample was predominantly low income; the average income-to-needs ratio (computed by taking the family income, exclusive of federal aid, and dividing this by the federal poverty threshold for that family) was 1.7 (SD = 1.5) with 48% of households having ratios lower than one (below the poverty line) and 69% of families having ratios lower than two. Additional demographic information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Statistics for the Study Participants and Variables (N = 341)

| Frequency (%) | Range | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Min | Max | |||

| Control Variables | ||||||

| Child age (months) | 46.9 | 6.6 | 32 | 61 | ||

| Child ethnicity | Hispanic | 222 (67%) | ||||

| White | 50 (15%) | |||||

| Asian | 21 (6%) | |||||

| Black | 11 (3%) | |||||

| Native American | 4 (1%) | |||||

| Other/Multi | 22 (7%) | |||||

| Languages spoken at home* | English | 209 (63%) | ||||

| Spanish | 207 (63%) | |||||

| Other | 19 (6%) | |||||

| Maternal education (yrs) | 13.0 | 3.1 | 8 | 20 | ||

| Family income | $37,500 | $30,561 | $2,500 | $87,500 | ||

| Predictor Variables: Children’s Engagement in the Classroom | ||||||

| Positive Engagement w/ Teachers | 2.15 | 0.53 | 1.21 | 4.33 | ||

| Positive Engagement w/ Peers | 2.46 | 0.52 | 1.33 | 4.62 | ||

| Positive Engagement w/Tasks | 3.48 | 0.57 | 2.13 | 5.36 | ||

| Negative Classroom Engagement | 1.64 | 0.35 | 1.00 | 3.06 | ||

| Outcome Variables: Children’s Regulation | ||||||

| Task orientation (teacher report) | Fall | 3.61 | 0.96 | 1.00 | 5.00 | |

| Spring | 3.79 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 5.00 | ||

| Compliance/EC (direct assessment) | Fall | 0.00 | 0.86 | −1.37 | 2.19 | |

| Spring | −0.01 | 0.86 | −1.58 | 1.56 | ||

| Emotion Regulation (teacher report) | Fall | 3.13 | 0.80 | 1.63 | 4.00 | |

| Spring | 3.18 | 0.57 | 1.63 | 4.00 | ||

| Observed Dysregulation (assessor report) | Fall | −0.00 | 0.66 | −1.21 | 2.91 | |

| Spring | −0.00 | 0.67 | −1.13 | 3.68 | ||

Note.

Parents may report more than one language spoken at home

All preschool classrooms met for half days only. Thirty-one percent had Head Start funding with the remaining centers being a mix of state and privately funded centers. The lead teacher in each classroom completed surveys describing demographic characteristics of the classroom. On average, 19 children per classroom were enrolled at the start of the school year (SD = 4), with 67% of children being of Hispanic origin, 15% White, non-Hispanic, and 18% of another ethnicity. Thirty three percent of children in their classes had limited English proficiency. All but two teachers were female, with 64% reporting Hispanic and 19% White race/ethnicity and 17% of other ethnicity. The average age of the teachers was 41 years old (SD = 10.82) with nearly 10 years of experience working professionally with children ages four and under (SD = 6.69). Thirty-seven percent of teachers reported a bachelor’s degree or beyond as their highest level of education (36% reported having an associate’s degree and 27% reported some post secondary training but no degree). Seventy three percent reported a degree in education or a related field with 29% of those majoring in early childhood education.

Procedures

Child observations and assessments

Lead preschool teachers allowed for access to their classroom for observations, direct assessment of children, and completed teacher (fall), classroom (fall), and child (fall and spring) surveys. At least two visits were made to each classroom, once in the fall and once in the spring. Observation visits were scheduled at the teachers’ discretion and lasted for roughly four hours. On each observation day, observers watched each of the four participating children in a series of alternating 15-minute cycles resulting in an average of four observation cycles per child in each classroom in the fall and spring. Observations continued across all activity settings, so data collectors recorded relevant setting information, such as the type of activity (e.g., large group, free choice, etc.), during each cycle.

Observations were conducted and teacher report of children’s behavior was collected for the entire sample in the fall and spring (except where children were unavailable in the spring due to withdrawal from the center or repeated absence). After completing observations in the fall, data collectors directly assessed two randomly selected children (one boy and one girl when possible). This resulted in a sub-sample of 197 children in the fall. Sixteen children could not be assessed in the spring due to attrition or absenteeism, so an additional 13 were selected from the original sample for a total sample of 210 children who were administered the direct assessments at either time point. These 210 children were similar to the full sample on all of the child and family demographics except that children in the subsample tended to come from families with higher incomes (t(317) = 2.63, p ≤ .001). Children were assessed in a quiet, private area of the preschool and administered a battery of assessments that lasted approximately 40 minutes. Data collectors were bilingual and administered the behavior regulation assessments in the language in which the child was most proficient (English or Spanish) based upon comparison of the child’s score on a test of receptive vocabulary administered in both languages.

Data collectors provided teachers a packet of questionnaires (teacher/classroom demographics and child rating scales) during the classroom visit in the fall and spring. Teachers mailed the completed packets to the research office and received $25 for their participation.

Data collector training

Data collectors attended a 2-day training session on the observation measure and were required to code and pass five reliability clips independently before observing live in the field. A passing score on the reliability clips was defined as scoring within one point of a master code on 80% of their scores. Data collectors completed an additional two days of didactic training on the administration of the direct child assessments and child ratings of self-regulation and were then assessed during live practice with four-year-olds to ensure that test administration and scoring skills were reliable and standardized prior to administering assessments in the field.

Measures

Demographic information

The parent survey provided information about their child’s gender, race/ethnicity, maternal education, family income, and languages spoken in the home.

Observation of children’s classroom engagement

The Individualized Classroom Assessment Scoring System (inCLASS; Downer et al., 2010) is an observational assessment of children’s classroom interactions, comprised of 10 dimensions: 1) Positive Engagement with the Teacher (attunement to the teacher, proximity seeking, and shared positive affect), 2) Teacher Communication (initiates conversations with the teacher, sustains conversations, and uses speech for varied purposes), 3) Teacher Conflict (aggression, noncompliance, negative affect, and attention-seeking directed toward the teacher), 4) Peer Sociability (proximity seeking, shared positive affect, popularity, perspective-taking, and cooperation), 5) Peer Assertiveness (positive initiations with peers, leadership, and self-advocacy), 6) Peer Communication (initiates conversations with peers, sustains conversations, and uses speech for varied purposes), 7) Peer Conflict (aggression, confrontation, negative affect, and attention-seeking directed toward peers), 8) Engagement with Tasks (sustained attention and active engagement), 9) Self-Reliance (personal initiative, independence, persistence, an self-direct learning), and 10) Behavior Control (patience, activity level matches classroom expectations, and physical awareness).

Each dimension is rated on a seven-point scale (guided by descriptors of behaviors that indicate low, medium, and high quality engagement) with higher ratings indicating higher quality and/or more frequent positive engagement within a dimension (except for Teacher and Peer Conflict where higher ratings indicate lower quality interactions). Exploratory factor analysis of these dimensions in an initial validity study (Downer et al., 2010) identified four domains of engagement which were used in the current study: positive engagement with teachers (Positive Engagement, Communication; r = .69), positive engagement with peers (Sociability, Assertiveness, Communication; r = .63 to. 75), positive engagement with tasks (Engagement, Self-Reliance; r =.44), and negative classroom engagement (Teacher Conflict, Peer Conflict, Behavior Control (reversed) r = .40 to 61). Children’s dimension scores were averaged across cycles to produce a domain score. Scores across the fall and spring were combined to form domain scores representing children’s engagement across the preschool year. For most children, the inCLASS subscale scores were based upon eight observation cycles (four in the fall and four in the spring) across a range of activity settings. Internal consistencies for the four domains using this study’s data in the fall, spring, or the Pre-K year combined were as follows: positive engagement with teachers (fall, α = .74; spring, α = .68; Pre-k year, α = .75); positive engagement with peers (fall, α = .83; spring, α = .77; Pre-k year, α = .83); positive engagement with tasks (fall, α = .72; spring, α = .69; Pre-k year, α = .72); and negative classroom engagement (fall, α = .74; spring, α = .77; Pre-k year, α = .79).

Inter-rater reliability was calculated across 22% of all cycles during live observations in the fall, and 10% of cycles in the spring, as two data collectors independently observed and rated the same children. Rater agreement within one point on the scale ranged from 87% to 100% across dimensions in the fall, and 92% to 99% in the spring; intraclass correlations averaged .85 (range .75–.93) in the fall and .73 (range .63–.86) in the spring. In terms of validity, previous analysis of the inCLASS found that the domain scores were significantly correlated with teacher ratings of children’s social and task-related skills (Downer et al., 2010).

Teacher report of children’s task orientation

The Task Orientation subscale of the Teacher-Child Rating Scale (TCRS; Hightower et al., 1986) was used as a teacher rating of children’s behavior and cognitive regulation within the classroom. The TCRS is a 38-item Likert-style rating scale with items rated on a five-point scale, with higher scores indicating that the item is more characteristic of the child. The Task Orientation subscale includes five items related to children’s approach to classroom activities: “completes work”, “well organized”, “functions well even with distractions”, “works well without adult support” and “a self starter”. A child’s ability to perform well on these items requires effortful control, behavioral inhibition, compliance of classroom rules and teacher commands, and inhibitory control in the classroom. In the current sample, Task Orientation showed high internal consistency in both the fall (α = .91) and spring (α = .91). The TCRS has been widely used to assess children in preschool and elementary school and has been related to measures of temperament, self-regulation, and children’s experiences in preschool (Gunnar, Tout, de Haan, Pierce, & Stansbury, 1997; Howes et al., 2008).

Teacher report of children’s emotion regulation

Teachers completed the Emotion Regulation Checklist (Shields & Cicchetti, 1997, 2001), which assesses the reporter’s perception of the child’s emotionality and regulation. This measure includes 23 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale from Never to Almost Always and includes two subscales—emotion regulation and negativity. The emotion regulation subscale was used in the current study and includes 8 items that assess aspects of emotion understanding and empathy and contains items such as “displays appropriate negative affect in response to hostile, aggressive or intrusive play” and “is a cheerful child.” Internal consistency of the subscale was good in the current sample (fall α = .75; spring α = .78).

Direct assessments of children’s compliance and executive control

Two regulation tasks from the Preschool Self-Regulation Assessment (PSRA) were used in this study (Smith-Donald, Raver, Hayes, & Richardson, 2007) - Pencil Tap and Toy Sort. These tasks have been used with young children and are related to teacher reports of classroom engagement, social skills, and academic achievement and have demonstrated measurement equivalence across ethnicity and gender (Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2009; Raver et al., 2008; see Smith-Donald et al., 2007). The Pencil Tap task was used to assess children’s executive functioning (Blair, 2002). Children were asked to tap a pencil on the table once when the tester tapped the table twice, and twice when the tester tapped the table once. Children were given three practice trials and 16 scored trials. Scores for this task represented the percent correct out of 16. The Toy Sort task was used to assess children’s compliance (NICHD, 1998). Children were asked to sort toys (cars, dinosaurs, bugs, and beads) into four bins without playing with them. Children were given two minutes to complete the sort before moving on to the next task. Scores for this task included latency (in seconds) for children to begin sorting and latency to complete sorting. Consistent with previously published work using is battery (Smith-Donald et al., 2007; Raver et al., 2008; Raver et al., 2011), a Compliance/Executive Control score was created by averaging the child’s standardized percent correct score on Pencil Tap and standardized reversed latency to complete the Toy Sort (fall r = .43; spring r = .46). Higher scores indicated greater regulation.

Data collector ratings of children’s dysregulation

At the conclusion of the assessment battery, data collectors rated children’s emotions, attention, and behavior, and confidence during the assessment battery using a likert survey that combined seven items from the Test Session Observations Checklist of the Woodcock Johnson-III Tests of Achievement (Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2001) as well as nine items from the PSRA Assessor report (Smith-Donald et al., 2007). Items were standardized and reverse scored (as needed) to be aggregated across the two sets of items. For this study, we used a subset of 9 items assessing children’s attention, emotion, and behavior dysregulation (excluding items assessing confidence). Example items included “level of activity (reversed)”, “attention and concentration (reversed)”, “negative response to difficult tasks”, “shows angry/irritable feelings or behavior”. Internal consistency of this subscale was good (fall α = .84; spring α = .83) with higher scores indicating greater dysregulation.

Data Analytic Approach

We fit a series of models to characterize how well children’s engagement with teachers, peers, and tasks predicted their development of self-regulation during the preschool year. Data were analyzed using Mplus Version 6.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010). Missing data for any one variable ranged between 3% and 20%. Analyses were run using maximum likelihood estimation so that data analyses using the teacher report as the outcome variable used data from all participants having some data (n = 341) and data analyses using direct assessments as the outcome variable used data from all participants who were selected for the direct assessments (n = 210). The hierarchical/organizational structure of the data where children (level 1) were nested within classrooms (level 2) was taken into account by using the COMPLEX command in Mplus. This approach adjusts the standard errors to take into account that children were clustered within classrooms. Models were fit using full information maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors. Each of the four self-regulation outcome variables was examined in a separate model. We used children’s spring self-regulation score as the outcome variable and controlled for the fall score by including it as a predictor variable. Demographic variables that have been linked to children’s self-regulation and have typically been included as control variables in the developmental literature were included as control variables— children’s ethnicity, whether English was spoken at home, maternal education, child gender, and child age (e.g. Moilanen, Shaw, Dishion, Gardner, & Wilson, 2020; Sektnan et al., 2010; Smith, Calkins, Keane, Anastopoulos, & Shelton, 2004; Wanless et al., 2011). Full models were fit which included covariates, the inCLASS dimension scores, the interactions between the inCLASS dimension scores, and the corresponding fall regulation score as predictors of children’s spring behavior regulation score. Covariate variables were coded as follows: for gender, boy = 1, girl = 0; for ethnicity, two variables were dummy coded, White, non-Hispanic = 1, and Other = 1 so that Hispanic served as the reference group; for home language, English spoken at home = 1, no English spoken at home = 0; maternal education and child age was centered at the grand mean. Interactions of continuous variables were plotted at +/− 1 SD from the mean (Aiken & West, 1991). We calculated effect sizes for the variables of interest by multiplying the coefficient with the standard deviation for the predictor, then dividing by the standard deviation for the self-regulation outcome (see Gutman, Sameroff, & Cole, 2003; Mashburn, Justice, Downer, and Pianta, 2009; NICHD ECCRN, & Duncan, 2003, for examples of using this approach to compute effect sizes in a multilevel modeling framework). However, it should be noted that there is not a single accepted method for calculating effect sizes in multi-level models (Roberts & Monoco, 2006; Snijders & Bosker, 1999).

Results

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics of predictor and outcome measures, all of which were adequately distributed and did not require transformations. Correlations between the predictor and outcome variables of interest are presented in Table 2. The results of the full hierarchical models examining the effects of children’s engagement with teachers, peers, and classroom tasks and activities on their development of self-regulation during preschool are presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix of Predictor and Outcome Variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Positive Engagement w/ Teachers | -- | .194 | .172 | .125 | .030 | .118 | .057 | .173 | .130 | .099 | .165 | −.017 |

| 2. Positive Engagement w/ Peers | -- | .447 | .081 | .076 | .082 | .232 | .243 | .173 | .183 | −.045 | −.048 | |

| 3. Positive Engagement w/ Tasks | -- | −.207 | .210 | .206 | .199 | .156 | .216 | .267 | −.139 | −.056 | ||

| 4. Negative Classroom Engagement | -- | −.224 | −.166 | −.092 | −.106 | −.119 | −.068 | .166 | .154 | |||

| 5. Fall Task Orientation | -- | .691 | .245 | .295 | .542 | .429 | −.333 | −.189 | ||||

| 6. Spring Task Orientation | -- | .287 | .199 | .444 | .598 | −.240 | −.140 | |||||

| 7. Fall Compliance/EC | -- | .621 | .180 | .307 | −.301 | −.223 | ||||||

| 8. Spring Compliance/EC | -- | .219 | .261 | −.304 | −.278 | |||||||

| 9. Fall Emotion Regulation | -- | .623 | −.089 | −.112 | ||||||||

| 10. Spring Emotion Regulation | -- | −.058 | −.063 | |||||||||

| 11. Fall Observed Dysregulation | -- | .348 | ||||||||||

| 12. Spring Observed Dysregulation | -- |

Note. Correlations in italics are significant at p <.05 and correlations in bold are significant at p < .01.

Table 3.

Effects of Interactions with Teachers, Peers, Tasks, and Conflict on Change in Children’s Behavioral Self-Regulation Skills during Preschool

| Task Orientation (teacher report) |

Compliance/ Executive Control (direct assessment) |

Emotion Regulation (teacher report) |

Dysregulation (assessor report) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | ||||||||

| Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | |

| Intercept | 3.93** | 0.09 | −0.04 | 0.10 | 3.17** | 0.05 | −0.24** | 0.07 |

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Fall Score | 0.57** | 0.06 | 0.49** | 0.09 | 0.58 | 0.06 | 0.35** | 0.09 |

| Age | 0.02** | 0.01 | 0.03** | 0.01 | 0.01* | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Gender (boy) | −0.18† | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.10 | −0.12* | 0.05 | 0.20* | 0.09 |

| English at home | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.14* | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.10 |

| Maternal Ed | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Other | −0.05 | 0.09 | −0.31* | 0.13 | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.12 |

| White | −0.18 | 0.14 | −0.41 | 0.16 | −0.05 | 0.09 | 0.23 | 0.18 |

| InCLASS | ||||||||

| Positive Engagement w/Teachers | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.27** | 0.10 | −0.03 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.09 |

| Positive Engagement w/Peers | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.07 | −0.19† | 0.11 |

| Positive Engagement w/Tasks | 0.11 | 0.09 | −0.07 | 0.10 | 0.12* | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.10 |

| Negative Classroom Engagement | −0.05 | 0.11 | −0.09 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.17 |

| InCLASS Interactions | ||||||||

| Positive Engagement w/Teachers* Positive Engagement w/Tasks |

0.31* | 0.12 | −0.33† | 0.19 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.17 |

| Positive Engagement w/Peers* Positive Engagement w/Tasks |

−0.24† | 0.12 | −0.08 | 0.11 | −0.03 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.11 |

| Positive Engagement w/Teachers* Negative Classroom Engagement |

−0.26 | 0.21 | 0.40† | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.18 | −0.67* | 0.29 |

| Positive Engagement w/Peers* Negative Classroom Engagement |

−0.59* | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.34 | −0.21 | 0.15 | 1.11** | 0.36 |

Note:

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01.

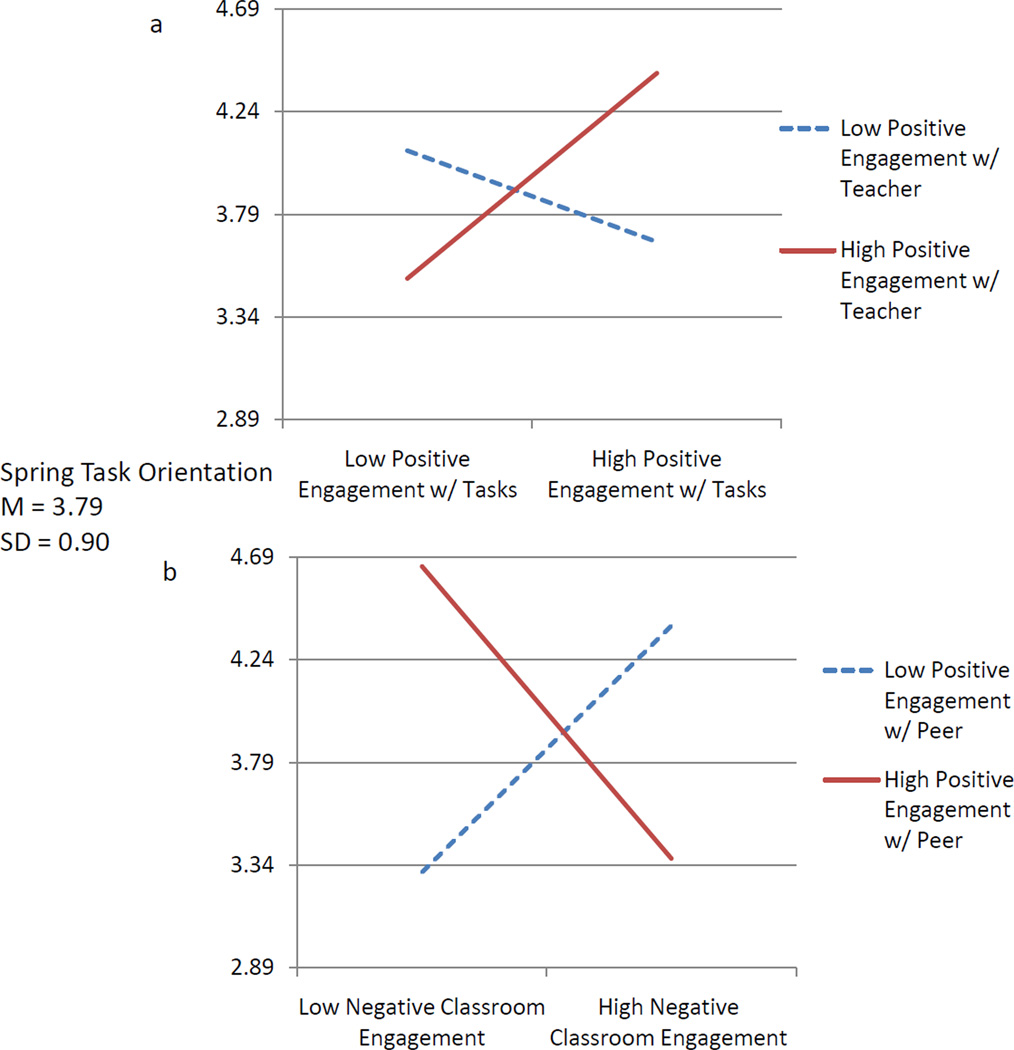

Task Orientation

Older children tended to evidence greater gains in task orientation during preschool as reported by their teachers (b = .02, SE = .01, p = .004). There were no significant main effects of the inCLASS domain scores on children’s task orientation. There were two significant interaction effects between the inCLASS domain scores. First, the interaction between positive engagement with teachers and positive engagement with task was associated with gains in teacher report of children’s task orientation. Specifically, when children’s positive engagement with teachers was high, children’s engagement with classroom tasks and activities was positively associated with gains in task orientation. In contrast, when children’s positive engagement with teachers was low, children’s engagement with classroom tasks and activities was negatively associated with gains in task orientation as reported by teachers (b = .31, SE = .12, p = .014; effect size = .11; see Figure 1a). Second, the interaction between positive peer engagement and negative classroom engagement was associated with gains in task orientation. When children’s positive engagement with peers was high, lower negative classroom engagement associated with greater gains in task orientation as reported by teachers. The opposite pattern held true when children positive engagement with peers was low—here, higher negative classroom engagement was associated with greater gains in task orientation (b = −.59, SE = .21, p = .005; effect size = .12; see Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Gains in children’s task orientation during the preschool year. (a) The effect of the interaction between children’s positive engagement with teachers and children’s positive engagement with tasks on children’s gains in task orientation. (b) The effect of the interaction between children’s positive engagement with peers and children’s negative classroom engagement on children’s gains in task orientation.

Compliance/Executive Control

Results indicated that after controlling the child’s fall score, older children tended to make greater gains in compliance/executive control during preschool (b = .03, SE = .01, p = .001) and children who were of minority ethnicity other than Hispanic made fewer gains in compliance/executive control compared to children who were Hispanic (b = −.31, SE = .13, p = .018) There was a main effect of positive engagement with teachers indicating that children who were more positively engaged with their teachers tended to make greater gains in compliance/executive control during the preschool year compared to children who were less positively engaged with their teachers (b = .27, SE = .10, p = .007; effect size = .17). Interaction effects between inCLASS domain scores were not predictive of gains in children’s compliance/executive control during preschool.

Emotion Regulation

Results indicated that after controlling the child’s fall score, older children (b = .012, SE = .01, p = .018), girls (b = −.12, SE = .05, p = .018), and children whose families spoke English at home (b = .14, SE = .06, p = .012) tended to make greater gains in emotion regulation as reported by teachers during preschool. There was a main effect of positive engagement with task indicating that children who were more actively engaged with classroom tasks and activities tended to make greater gains in emotion regulation during the preschool year compared to children who were less actively engaged with classroom tasks and activities (b = .12, SE = .06, p = .039; effect size = .12). Interaction effects between inCLASS domain scores were not predictive of gains in children’s emotion regulation during preschool.

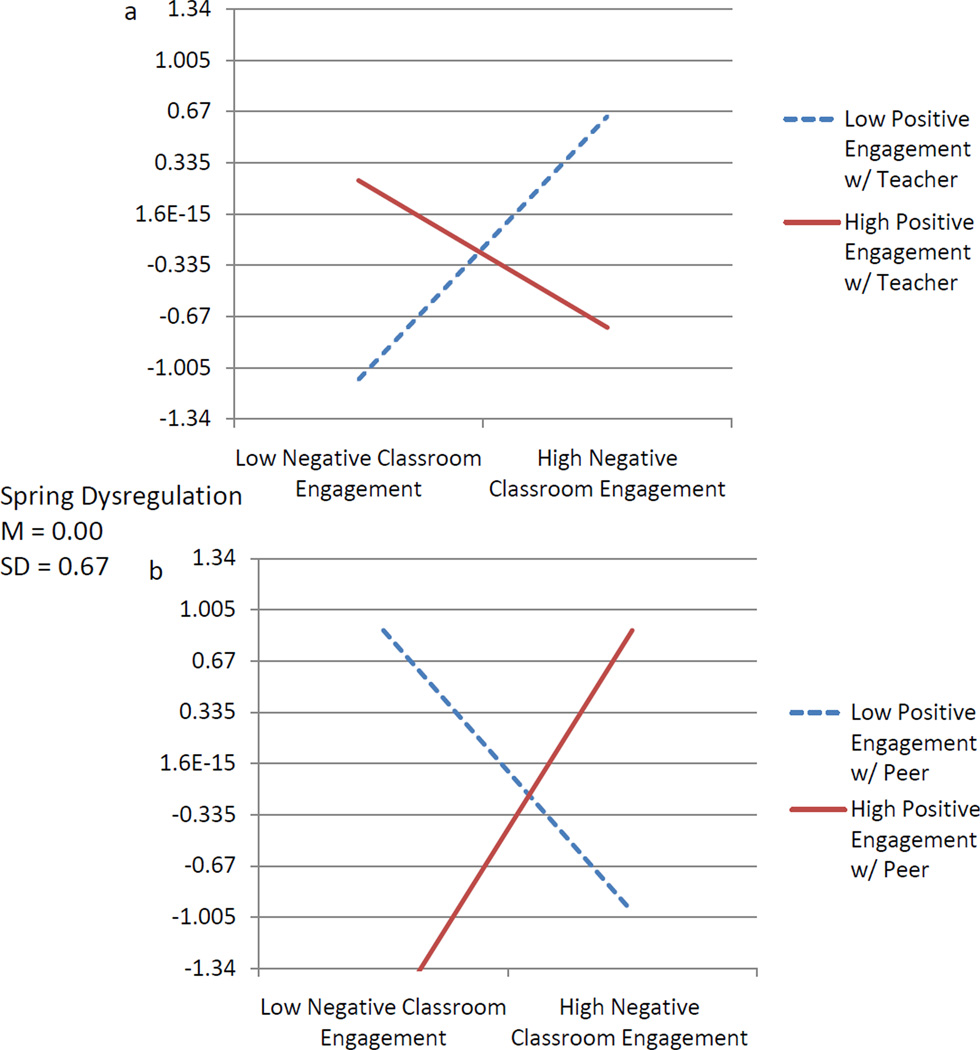

Dysregulation

Girls tended to evidence greater reduction in dysregulation during preschool as observed and rated by assessors (b = .20, SE = .09, p = .027). There were no significant main effects of the inCLASS domain scores on children’s dysregulation. There were two significant interaction effects between the inCLASS domain scores. First, the interaction between positive engagement with teachers and negative classroom engagement was associated with reductions children’s dysregulation. When children’s negative classroom engagement was high, children’s positive engagement with teachers was positively associated with reductions in dysregulation during preschool. However, the opposite was true when children’s negative classroom engagement was low. Here, children’s positive engagement with teachers was negatively associated with their reductions in dysregulation (b = −.67, SE = .29, p = .022; effect size = .21; see Figure 2a). Second, the interaction between positive engagement with peers and negative classroom engagement was associated with reductions in children’s dysregulation. When children’s negative classroom engagement was low, children’s positive engagement with peers was associated with greater reductions in dysregulation. However, when children’s negative classroom engagement was high, children’s positive engagement with peers was associated with smaller reductions in dysregulation (b = 1.11, SE = .36, p = .002; effect size = .30; see Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Reductions in children’s dysregulation during the preschool year. (a) The effect of the interaction between children’s positive engagement with teachers and children’s negative classroom engagement on children’s reductions in dysregulation. (b) The effect of the interaction between children’s positive engagement with peers and children’s negative classroom engagement on children’s reductions in dysregulation.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine how preschool children’s individual engagement with teachers, peers, and classroom tasks and activities related to their development of self-regulation skills during the preschool year in a predominantly Hispanic sample of children from low-income families. We expected that positive engagement with teachers, peers, and tasks in the classroom would be linked with greater increases in children’s regulatory skills during preschool. And, in accordance with Vygotsky’s theory of development within the sociocultural context we expected that being positively and prosocially engaged with teachers or peers in combination with active engagement in classroom tasks and activities and low negative classroom engagement would be especially supportive of children’s gains in regulation during preschool. The results were supportive of our hypotheses in that we found that some combination of children’s engagement with teachers, peers, and/or tasks during preschool was associated with their development of self-regulation across all outcome measures.

We found that children’s positive interactions with teachers—high emotional connection, expressed positive emotions, and adaptive communication with teachers— were related to gains in compliance/executive control. We also found that children who were actively and positively engaged in classroom tasks and activities made gains in emotion regulation skills during preschool. These significant main effects are consistent with prior research (e.g., Bierman et al., 2009; Raver et al., 2011; Trentacosta & Izard, 2007) and provide support that children’s engagement in the preschool classroom is associated with the development of self- regulation. However, we did not find a significant main effect of children’s engagement with peers and gains in their self-regulation.

In accordance with Vygotsky’s theory of development within the sociocultural context we expected that being positively and prosocially engaged with teachers or peers in combination with active engagement in classroom tasks and activities and low negative classroom engagement would be especially supportive of children’s gains in regulation during preschool.

We found support for several of our hypotheses regarding interactions between types of classroom engagement and children’s self-regulation outcomes, particularly for task orientation and dysregulation. These moderation results were partially supportive of the emphasis that Vygotsky placed on the context or environment for learning and development and for his view that learning occurs through shared engagement with other individuals. Specifically, children made gains in task orientation when they were more actively and positively engaged in classroom tasks and activities while also being positively engaged with teachers. There was also a significant interaction effect for engagement with peers and negative engagement in the classroom such that children made gains in task orientation when they were highly positively engaged with peers, and had low negative classroom engagement.

We also found that for children who tended to engage more negatively within the classroom, higher positive teacher engagement was associated with greater reductions in dysregulation. In addition, we found children evidenced reductions in dysregulation during preschool when they were less negatively engaged in the classroom while also being more positively engaged with peers. Vygotsky asserted that a child’s ability to stay on task and engage successfully within the learning environment (in other words, to regulate one’s self) depends upon the positive and active engagement with teachers and peers and that interdependence and reliance on others are fundamental to the development of self-regulation (Stetsenko & Vianne, 2009).

These results are also consistent with research indicating that teacher-child classroom interactions facilitate their development of school readiness skills (Hamre & Pianta, 2005; Mashburn, et al., 2008). Unfortunately, observational studies of preschool classrooms indicate wide variability in the quality of children’s interactions with teachers, peers, and learning materials across programs. The overall quality of these interactions measured at the classroom level is often mediocre or low, especially with respect to teachers’ instructional interactions with teachers rarely expanding children’s thinking, understanding, and/or language (Burchinal et al., 2008; Pianta et al., 2005). Thus, children’s interactions in the early childhood setting should be a central focus of both investigation and intervention efforts in early childhood education (Pianta, Mashburn, Downer, Hamre, & Justice, 2008; Raver et al., 2008). By using an observational measure that examined teacher-child interactions at the individual child level rather than assessing teacher-child interactions as the classroom level, we have added to the literature.

We acknowledge that certain interaction patterns present in these moderation results were not hypothesized and were difficult to interpret. For example, we found that for children who had low levels of negative classroom engagement, positive engagement with teachers was not associated with reductions in dysregulation. It appears that these children are already evidencing good emotional and behavioral regulation in their day-to-day classroom interactions and so may not need extra support from teachers to develop these regulation skills. With regard to children’s peer engagement, we found that for children who tended to display higher negative classroom engagement, positive peer interactions were not supportive of their self-regulation development (these children made few gains in task orientation and few reductions in dysregulation during preschool). Perhaps positive peer interactions need to occur in the context of positive classroom engagement in order to be supportive of self-regulation development. For example, it may be that peer play must be combined with activities that require negotiation of social interactions (e.g. sharing, taking turns) in order to facilitate their ability to regulate their own behavior and emotions. Less research has examined the effect of how children’s engagement with peers during the preschool day may facilitate development of children’s regulation. There is some research that indicates that peer play interactions supports children’s development of problem solving, reasoning, and perspective taking skills (Diamond, Barnett, Thomas, & Monro, 2007). For example, work by Fantuzzo, Sekino, and Cohen (2004) found that children attending Head Start who demonstrated high levels of interactive peer play behaviors early during the year evidenced greater social-emotional skills at the end of the year. In contrast, disruptive and disconnected peer play was associated with negative emotional and behavioral outcomes. Positive peer interactions may be supportive of children’s self-regulatory behavior when they are carefully scaffolded by a teacher. However, in our study, positive peer engagement and positive teacher engagement were not highly correlated (r = .19) indicating that teachers were not often engaging with children when they were engaging with their peers. Thus, teachers were likely not providing the needed scaffolding that would allow for children’s overall classroom engagement to be adaptive enough that their peer interactions would be supportive of children’s self-regulation. Future research should examine explicitly whether the positive impacts of peer interactions need to occur within the context of positive teacher support/facilitation in order to have benefits for children’s development of self-regulation.

Taken as a whole, the results of this study, indicating that children’s engagement with teachers, peers, and classroom tasks and activities is associated with changes in their self-regulation skills during preschool, are consistent with recent interventions that have been designed to foster children’s self-regulation skills by promoting engagement with teachers and peers, in concert with children’s engagement with learning activities. Specific curricula have been designed to increase children’s interactions with peers in the classroom as a way to enhance their behavioral regulation. In a study implemented by Webster-Stratton and colleagues, children who engaged in teacher-implemented activities that were specifically designed to improve socials skills evidenced greater increases in emotional and behavioral regulation skills (Webster-Stratton, Reid, & Hammond, 2004). As another example, in Tools of the Mind, an early childhood curriculum developed by Bodrova and Leong (2007) that is based on Vygotskian theory, teacher-structured peer interactions are encouraged in order to enhance learning. These interactions include having an “expert” peer work with a “novice” peer on a joint task or on interrelated tasks where each peer has a specific role (Bodrova & Leong, 2007). A randomized controlled trial of Tools of the Mind showed that children in Tools classrooms scored higher on behavioral regulation compared to children not in the program (Diamond et al., 2007). This research suggests that children’s engagement with teachers and peers in the context of classroom tasks and activities can have an influence on the development of their self-regulatory skills.

Limitations

This study adds to the literature base on how the quality of children’s preschool experience is associated with young children’s gains in self-regulation during the preschool year. However, several limitations deserve attention. Although this was a short-term longitudinal study, it was correlational in nature and so it is not possible to infer a causal relationship. The associations between children’s engagement in the classroom and development of self-regulation are almost certainly transactional in nature—that is, children’s experiences in the early childhood classroom impact their self-regulation skills (Gunnar, 2003; Noble et al., 2005; Raver et al., 2011) and the children’s increased self-regulation skills influence their classroom experiences (Eisenberg et al., 2010; Phillips, Fox, & Gunnar, 2011). More frequent engagement in positive interactions with teachers and peers and active engagement in classroom tasks and activities may contribute to greater development of behavioral control. Alternatively, one would expect that children with better behavioral regulation skills would be more successful at staying focused on tasks and activities and display behaviors such as the ability to maintain physical awareness and to share toys that will allow them to maintain more positive engagement with teachers and peers. Additional longitudinal research in this area is needed to tease apart the directionality of these important relations.

We also acknowledge that our models were not fully predictive and that there are other important aspects of the classroom environment not assessed in this study that may have also predicted children’s regulation. Future studies should include measures of global classroom quality, classroom resources, and the specific types of experiences that teachers provide for children. A strength of this study was the use of a multi-method, multi-informant assessment of children’s self-regulation. However, it is not possible to determine whether the differing patterns of how children’s engagement with teachers, peers, and tasks was associated with their gains in self-regulation was due to different child interactions being more or less important for different aspects of self-regulation (e.g. positive teacher teacher-child interactions are particularly important for the development of compliance and executive control) versus differences in measurement methods (e.g., direct assessment versus teacher report). Thus, replication of these results is necessary.

Generalizability

Finally, the generalizability of our results are limited to urban, predominantly Hispanic children from low-income families—a population of children that is growing and with whom more research is needed. There is almost no research on the development of children’s social-emotional competencies in Hispanic children. The research that does exist suggests that there are moderate disparities between Hispanic and White children with regards to the social competence, but these findings are largely accounted for by socioeconomic status (Galindo & Fuller, 2010; Wanless et al., 2011). Further research is needed to examine the developmental trajectories of Hispanic children’s social competence, and results should be disaggregated by sub-groups with this population (e.g., social class, home language, etc.).

In addition, recent research indicates that the quality of children’s early experiences matters most for at-risk children (Burchinal, Ramey, Reid, & Jaccard, 1995; McCartney, 2010), and there is evidence that the quality of teacher-child interactions is predictive of children’s outcomes in classrooms with large proportions of Hispanic children (Downer et al., in press). However, research is needed on whether there are specific classroom interactions that may be particularly important in supporting the development of Hispanic children’s social competence. Future research should focus on exploring whether there are cultural differences in pathways leading to the development of behavioral self-regulation skills.

Conclusion

Self-regulation has been conceptualized as a core feature of school readiness—one that underlies the skills of successful school achievement (Blair, 2002). Failures of early self-regulation are considered to be both core features of childhood psychological problems and factors that constrain subsequent development and the child’s response to later developmental challenges, such as the transition to school, establishing positive peer relationships, and academic achievement (Calkins & Fox, 2002; Calkins & Williford, 2009; Keenan, 2000). Children’s behavioral control develops substantially during the preschool years and prior research has indicated that self-regulation is influenced by exposure to preschool and teachers’ classroom interactions and teacher implemented interventions (Mashburn et al, 2008; Shields et al., 2001; Webster-Stratton, Reid, & Stoolmiller, 2008). Our results indicated that children’s positive engagement within the early childhood classroom was associated with gains in their behavioral regulation skills during the preschool year. Systematically observing how a child interacts with other children, teachers, and learning activities in the preschool classroom holds potential to inform the creation of professional development aimed at supporting teachers in fostering an individual child’s development within the early education classroom environment.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the Interagency Consortium on Measurement of School Readiness through Grant R01 HD051498 to the University of Virginia. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent views of the funders. We extend our gratitude to the teachers, parents, and children who invited us into their classrooms.

References

- Adams G, Tout K, Zaslow M. Early care and education for children from low-income families: Patterns of use, quality, and potential policy implications. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alloway T, Gathercole S, Adams A, Willis C, Eaglen R, Lamont E. Working memory and phonological awareness as predictors of progress towards early learning goals at school entry. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2005;23:417–426. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony JL, Lonigan CJ, Driscoll K, Phillips BM, Burgess SR. Phonological sensitivity: A quasi-parallel progression of word structure units and cognitive operations. Reading Research Quarterly. 2003;38(4):470–487. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett J. Caregivers in day-care centers: Does training matter? Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1989;10:541–522. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Vohs KD. Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications. New York: Guilford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL, Torres MM, Domitrovich CE, Welsh JA, Gest SD. Behavioral and cognitive readiness for school: Cross-domain associations for children attending Head Start. Social Development. 2009;18(2):305–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00490.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch SH, Ladd GW. Interpersonal relationships in the school environment and children's early school adjustment: The role of teachers and peers. Social motivation: Understanding children's school adjustment. In: Juvonen J, Wentzel K, editors. Social motivation: Understanding children's school adjustment, Cambridge studies in social and emotional development. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 199–225. [Google Scholar]

- Birch SH, Ladd GW. The teacher-child relationship and children’s early school adjustment. Journal of School Psychology. 1997;35:61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Birch SH, Ladd GW. Children’s interpersonal behaviors and the teacher-child relationship. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:934–946. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.5.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C. School readiness: Integrating cognition and emotion in a neurobiological conceptualization of child functioning at school entry. American Psychologist. 2002;57:111–127. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.57.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair KA, Denham SA, Kochanoff A, Whipple B. Playing it cool: Temperament, emotion regulation, and social behavior in preschoolers. Journal of School Psychology. 2004;42:419–443. [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, Razza RP. Relating effortful control, executive function, and false belief understanding to emerging math and literacy ability in kindergarten. Child Development. 2007;78:647–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodrova E, Leong DJ. Learning and development of preschool children from a Vygotskian perspective. In: Kozulin A, Gindis B, Ageyev V, Miller S, editors. Vygotky’s Educational Theory in Cultural Context. NY: Cambridge University Press; 2003. pp. 156–176. [Google Scholar]

- Bodrova E, Leong DJ. Self-regulation as a key to school readiness: How early childhood teachers can promote this critical competency. In: Zaslow M, Martinez-Beck I, editors. Critical issues in early childhood professional development. Baltimore, MD: Brookes; 2006. pp. 203–224. [Google Scholar]

- Bodrova E, Leong DJ. Tools of the mind: The Vygotskian approach to early childhood education. second edition. Columbus, OH: Pearson; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bulotsky-Shearer RJ, Fanuzzo JW, McDermott PA. An investigation of classroom situational dimensions of emotional and behavioral adjustment and cognitive and social outcomes for Head Start children. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:139–154. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal M, Howes C, Pianta RC, Bryant D, Early D, Clifford R, et al. Predicting child outcomes at the end of kindergarten from the quality of pre-kindergarten teacher-child interactions and instruction. Applied Developmental Science. 2008;12:140–153. [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal MR, Peisner-Feinberg E, Bryant DM, Clifford R. Children's social and cognitive development and child-care quality: Testing for differential associations related to poverty, gender, or ethnicity. Applied Developmental Science. 2000;4(3):149–165. [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal MR, Ramey SL, Reid MK, Jaccard J. Early child care experiences and their association with family and child characteristics during middle childhood. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 1995;10(1):33–61. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD. Cardiac vagal tone indices of temperamental reactivity and behavioral regulation in young children. Developmental Psychobiology. 1997;31:125–135. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2302(199709)31:2<125::aid-dev5>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD. The emergence of self-regulation: Biological and behavioral control mechanisms supporting toddler competencies. In: Brownell C, Kopp C, editors. Socioemotional development in the toddler years: Transitions and transformations. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Fox NA. Self-regulatory processes in early personality development: A multilevel approach to the study of childhood social withdrawal and aggression. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:477–498. doi: 10.1017/s095457940200305x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Williford AP. Taming the terrible twos: Self-regulation and school readiness. In: Barbarin OA, Wasik BH, editors. Handbook of child development and early education: Research to practice. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 172–198. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, von Stauffenber C. Child characteristics and family processes that predict behavioral readiness for school. In: Crouter A, Booth A, editors. Early disparities in school readiness: How families contribute to transitions into school. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2008. pp. 225–258. [Google Scholar]

- Castro DC, Páez MM, Dickinson DK, Frede E. Promoting language and literacy in young dual language learners: Research, practice, and policy. Child Development Perspectives. 2011;5:15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Chang F, Burns BM. Attention in Preschoolers: Associations With Effortful Control and Motivation. Child Development. 2005;76(1):247–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements DH, Sarama J. Experimental evaluation of the effects of a research-based preschool mathematics curriculum. American Educational Research Journal. 2008;45(2):443–494. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R, Leventhal T, Wirth RJ, Pierce KM, Pianta RC. Family socioeconomic status and consistent environmental stimulation in early childhood. Child Development. 2010;81:972–987. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01446.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson BA, Williams SA. The impact of language status as an acculturative stressor on internalizing and externalizing behaviors among Latino/a children: A longitudinal analysis from school entry through third grade. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37:399–411. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A, Barnett WS, Thomas J, Munro S. Preschool program improves cognitive control. Science. 2007;318:1387–1388. doi: 10.1126/science.1151148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll B, Lyon MA. Risk and resilience: Implications for the delivery of educational and mental health services in schools. School Psychology Review. 1998;2:348–363. [Google Scholar]

- Domitrovich CE, Greenberg MT. Preventive Interventions with young children: Building on the foundation of early intervention programs. Early Education and Development. 2004;15(4):365–370. [Google Scholar]

- Downer JT, Booren LM, Lima OK, Luckner AE, Pianta RC. The Individualized Classroom Assessment Scoring System (inCLASS): Preliminary reliability and validity of a system for observing preschoolers’ competence in classroom interactions. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2010;25(1):1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downer JT, López ML, Grimm K, Hamagami A, Pianta RC, Howes C. Observations of teacher-child interactions in classrooms serving Latinos and Dual Language Learners: Applicability of the Classroom Assessment Scoring System in diverse settings. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Downer J, Pianta RC. Academic and cognitive functioning in first grade: Associations with earlier home and child care predictors and with concurrent home and classroom experiences. School Psychology Review. 2006;35(1):11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Guthrie IK, Fabes RA, Shepard S, Losoya S, Murphy BC, et al. Prediction of elementary school children's externalizing problem behaviors from attention and behavioral regulation and negative emotionality. Child Development. 2000;71:1367–1382. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Karbon M, Murphy BC, Wosinski M, Polazzi L, et al. The relations of children's dispositional prosocial behavior to emotionality, regulation, and social functioning. Child Development. 1996;67:974–992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Nyman M, Bernzweig J, Pinuelas A. The relations of emotionality and regulation to children's anger-related reactions. Child Development. 1994;65:109–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Guthrie IK, Fabes RA, Shepard S, Losoya S, Murphy BC, et al. Prediction of elementary school children's externalizing problem behaviors from attention and behavioral regulation and negative emotionality. Child Development. 2000;71:1367–1382. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Valiente C, Eggum ND. Self-regulation and school readiness. Early Education and Development. 2010;21:681–698. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2010.497451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhower AS, Baker BL, Blacher J. Early student-teacher relationships of children with and without intellectual disability: Contributions of behavioral, social, and self-regulatory competence. Journal of School Psychology. 2007;45:363–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias C, Berk LE. Self-regulation in young children: Is there a role for sociodramatic play? Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2002;17(2):216–238. [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Rosenbaum J. Self-regulation and the income-achievement gap. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2008;23:504–514. [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzo J, Perry M, McDermott P. Preschool approaches to learning and their relationship to other relevant classroom competencies for low-income children. School Psychology Quarterly. 2004;19(3):212–230. [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzo J, Sekino Y, Cohen H. An examination of the contributions of interactive peer play to salient classroom competencies for urban Head Start children. Psychology in the Schools. 2004;41(3):323–336. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo C, Fuller B. The social competence of Latino kindergartners and growth in mathematical understanding. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:579–592. doi: 10.1037/a0017821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg C. Teaching English Language Learners: What the research does-and does not-say. American Educator. 2008;32:8–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR. Integrating neuroscience and psychological approaches in the study of early experiences. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;1008:238–247. doi: 10.1196/annals.1301.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Tout K, de Haan M, Pierce S, Stansbury K. Temperament, social competence, and adrenocortical activity in preschoolers. Developmental Psychobiology. 1997;1:65–85. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2302(199707)31:1<65::aid-dev6>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman LM, Sameroff AJ, Cole R. Academic growth curve trajectories from 1st grade to 12th grade: Effects of multiple social risk factors and preschool child factors. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:777–790. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.4.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamre BK, Pianta RC. Early teacher-child relationships and the trajectory of children’s school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Development. 2001;72:625–638. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamre BK, Pianta RC. Can instructional and emotional support in the first grade classroom make a difference for children at risk of school failure? Child Development. 2005;76(5):949–967. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms T, Clifford RM, Cryer D. Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale – Revised Edition. New York, NY: Teachers College Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hightower AD, Work WC, Cowen EL, Lotyczewski BS, Spinell AP, Guare JC. The teacher-child rating scale: A brief objective measure of elementary chidlren’s school problem behaviors and competencies. School Psychology Review. 1986;15:393–409. [Google Scholar]

- Howes C. Social-emotional classroom climate in child care, child–teacher relationships and children's second grade peer relations. Social Development. 2000;9(2):191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Howes C, Burchinal M, Pianta R, Bryant D, Early D, Clifford R, Barbarin O. Ready to learn? Children’s pre-academic achievement in pre-Kindergarten programs. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2008;23:27–50. [Google Scholar]