Abstract

Anthracyclines and taxanes are cytotoxic agents that are commonly used for the treatment of breast cancer, including in the adjuvant, neoadjuvant, and metastatic setting. Each drug class of is associated with cumulative and potentially irreversible toxicity, including cardiomyopathy (anthracyclines) and neuropathy (taxanes). This may either limit the duration of therapy for advanced disease, or prevent retreatment for recurrence if previously used as component of adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy. Several classes of cytotoxic agents have been evaluated in patients with anthracycline and taxane-pretreated metastatic breast cancer (MBC), including other antitubulins (vinorelbine, ixabepilone, eribulin), antimetabolites (capecitabine, gemcitabine), topoisomerase I inhibitors (irinotecan), platinum analogues (cisplatin, carboplatin), and liposomal doxorubicin preparations. No trials have shown an overall survival advantage for combination chemotherapy in this setting, indicating that single cytotoxic agents should usually be used, expect perhaps in patients with rapidly progressive disease and/or high tumor burden.

Keywords: Metastatic breast cancer, MBC, Chemotherapy, Cytotoxic agents, Anthracycline, Taxane, Pretreated, Systemic cytotoxic therapy, Drug resistance

Introduction

Anthracyclines and taxanes are the two most active classes of cytotoxic agents for early and advanced stage breast cancer, and are thus commonly used as a component of either adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy1, and/or in patients with metastatic breast cancer (MBC).2 Anthracyclines are generally not used for metastatic disease if previously used for adjuvant therapy because of the potential for cumulative cardiac toxicity, although liposomal anthracyclines may be safely used in patients with a history of prior anthracyclines exposure.3 Anthracyclines are also often not considered even if there has been no prior adjuvant exposure because they are generally less effective than taxanes as first line therapy4,5, and because there are often other alternatives for second-line therapy or beyond. The purpose of this review is to summarize available information about cytotoxic agents that have been evaluated specifically in patients with anthracycline and taxane pretreated metastatic breast cancer (MBC), with a focus on pivotal phase II or III trials which contributed to drug approval or provided important information that has informed the use of commonly used cytotoxic agents in this setting.

Goals of Systemic Cytotoxic Therapy

Cytotoxic therapy is generally reserved for patients with “triple negative” cancers, estrogen-receptor (ER)-positive cancers that have become resistant to endocrine therapy, or cancers that are rapidly progressive and/or associated with high visceral tumor burden. Cytotoxic therapy is commonly used in combination with anti-HER2 directed therapy in patients with HER2/neu overexpressing disease because it has been shown to improve survival compared with chemotherapy alone. 6 For patients with hormone receptor positive disease, however, concurrent use of chemotherapy plus endocrine therapy is not more effective chemotherapy alone.7 Virtually all patients with MBC will receive chemotherapy during some point in their course, expect perhaps the very elderly, frail, or infirm.

Although patients with distant metastatic disease are generally regarded as incurable, systemic cytotoxic therapy improves survival, delays the progression of disease, and may result in symptom palliation. 8,9,10 Moreover, up to 10% of patients with MBC may survive beyond 10 years or longer, particularly if there has been an objective response to cytotoxic therapy.11 Of the hundreds of phase III trials in MBC that have been performed over the past three decades, survival for the experimental arm was significantly improved in only of handful.6,12–14 Despite difficulty in demonstrating improved survival in individual trials, population-based studies suggest that patients with MBC are now surviving modestly longer than in the past.15–17 The improvement observed in population-based studies may be due to the increased availability of drugs which when used individually have no or minimal effect in prolonging survival, but when used sequentially can produce modest survival gains. On the other hand, other studies suggest this improved survival in recent years for patients who relapse after adjuvant chemotherapy may be evident only in patients with a short relapse free interval, suggesting that this effect may be attributable to the availability of anti-HER2 directed in more recent years rather than the availability of new cytotoxic agents.18

Resistance to Cytotoxic Therapy

Although most patients experience objective response or some period of disease stabilization after cytotoxic therapy for metastatic disease, resistance invariably develops. Although there is no accepted standardized definition of resistance, some very large phase III trials have provided very specific definitions used to select patients for inclusion in the trials. 19,20 Resistance is not synonymous with pretreatment. For the purpose of this review, “pretreatment” is defined as prior exposure to an agent as a component of therapy in the adjuvant, neoadjuvant, or metastatic setting. “Resistance” is defined as disease progression during therapy for metastatic disease, or relapse during our to 6–12 months after completing adjuvant therapy, a definition that has correlated with lower response rates and shorter time to disease progression when cytotoxic therapy is used in the second-line or beyond.21 Patients who relapse beyond 12 months after completing adjuvant chemotherapy exhibit comparable clinical benefit when retreated with to same regimen as those not pretreated. 22,23

Mechanisms of Drug Resistance

There are several mechanism of drug resistance that have been identified, including P-glycoprotein mediated drug resistance (MDR-1 or MRP) that may influence sensitivity to multiple agents, or mechanisms associated with resistance to specific agents or drug classes, such as topoisomerase II gene amplification (anthracyclines) or alterations in glutathione levels (alkylating agents) or beta-tubulin isoform expression (antitubulins). Use of cytotoxic agents in combination is a strategy that has been used for overcoming resistance to therapy. 24 The use of agents to reverse drug resistance, such as P-glycoprotein modifying agents, have been ineffective.25 There are no clinically validated assays that define drug resistant tumors.

Approach to the Patient with Anthracycline and Taxane-Pretreated Metastatic Breast Cancer

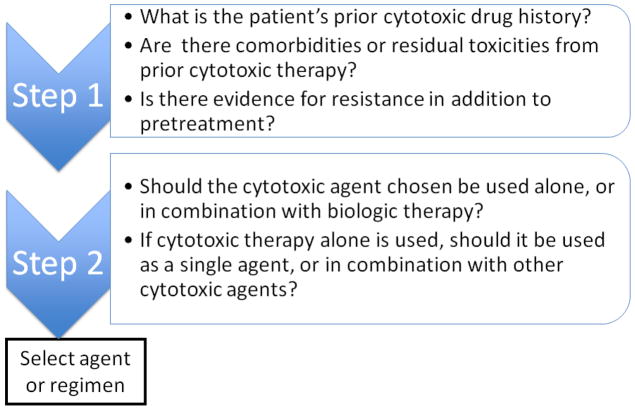

In approaching a patient in this scenario, the following questions should be considered in formulating a treatment plan for an individual patient, as shown in Figure 1. First, what is the patient’s prior cytotoxic drug history? This will influence the selection of agents for defining a “menu” of potentially suitable agents. Second, are there comorbidities or residual toxicities from prior cytotoxic therapy? This may limit the menu of potentially suitable agents that were initially defined in reviewing the treatment history. Third, is there evidence for resistance in addition to pretreatment? Fourth, should the cytotoxic agent chosen be used alone, or in combination with biologic therapy? Patients with HER2/neu overexpressing disease should almost always receive anti-HER2 directed therapy in combination with cytotoxic therapy because of evidence that concurrent therapy improves clinical outcomes compared with cytotoxic therapy alone. 6,26 Fifth, if cytotoxic therapy alone is used, should it be used as a single agent, or in combination with other cytotoxic agents? Single cytotoxic agents should be suitable in most cases, although combination therapy may be considered in patients with rapidly progressive disease, high visceral tumor burden, or impaired performance status that is often associated with the former.

Figure 1.

Algorithm for selecting chemotherapy regimen

Cytotoxic Agents Commonly Used for Anthracycline and Taxane-Pretreated Metastatic Breast Cancer

There are currently three cytotoxic drugs approved for anthracycline and taxane-pretreated MBC, including capecitabine, ixabepilone and eribulin. Some are approved as monotherapy only (eribulin), whereas others are approved either as monotherapy or in combination (capecitabine, ixabepilone). Other agents that are not specifically approved for this indication but are commonly used in clinical practice either alone or in combination with other cytotoxic agents and/or biologics include antimetabolites (gemcitabine), platinum analogues (cisplatin, carboplatin), antitubulins (vinorelbine, docetaxel), topoisomerase I inhibitors (irinotecan), liposomal anthracyclines (pegylated liposomal anthracyclines), and other agents that are rarely used because of their toxicity profile (mitomycin-C). The mechanism of action are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selected cytotoxic agents that have activity in patients with anthracycline- and taxane-pretreated metastatic breast cancer

| Drug Class | Agent | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Antimetabolites | Capecitabine | Inhibits thymidylate synthetase |

| Gemcitabine | Inhibits processes required for DNA synthesis | |

| Antitubulins | ||

| Ixabepilone (Epothilone B analog) | Stabilize microtubules by inhibiting both growth and shortening of microtubules | |

| Eribulin (Halichondrin B analog) | Stabilizes microtubules by suppressing microtubule growth (with no effect on microtubule shortening) and sequestering tubulin into nonfunctional aggregates | |

| Vinorelbine (vinca alkaloid) | Inhibits microtubule formation by Inhibiting the polymerization of tubulin dimmer | |

| Platinum analogues | ||

| Carboplatin | DNA adduct formation | |

| Cisplatin | DNA adduct formation | |

| Anthracyclines | ||

| Doxorubicin | DNA intercalation, Topoisomerase II inhibitor | |

| Camptotehcin | ||

| Irinotecan | Topoisomerase I inhibitor |

Capecitabine

Capecitabine is an orally available prodrug that is enzymatically converted to the antimetabolite 5-flourouracil (5-FU). It was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) based upon activity observed in phase II trials in patients with anthracycline and taxane pretreated MBC.27 Using a capecitabine dose and schedule of 1250 mg/m2 PO BID for 14 days of every 21 days in 163 patients with MBC who had 2–3 prior chemotherapy regimens for MBC, the objective response rate was 20%, median response duration was 8.1 months, and median overall survival was 12.8 months. The most common grade 3–4 side effects included diarrhea (14%) and hand-foot syndrome (10%), and dose reductions for toxicity were common. Clinicians typically use lower doses (1000 mg/m2 PO BID) and different schedules (1 week on/1 week off), which appear to improve tolerability without compromising efficacy 28,29 Although the drug is available in 500 mg and 150 mg tablets, most clinicians round the dose to the nearest 500 mg, resulting in greater patient convenience. Capecitabine monotherapy is also commonly as first-line therapy for MBC because it is not produce alopecia or myelosuppression.

Capecitabine has also been evaluated in combination with biological agents. In HER2/neu overexpressing disease, the combination of the HER2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor lapatinib was shown to be more effective than capecitabine alone in patients with disease resistant to trastuzumab plus taxane therapy, and is an approved combination. In predominantly HER2 non-expressing disease, a phase III trial found that although the addition of bevacizumab to capecitabine improved the response rate (19.8% vs. 9.1%; P = .001) in patients with anthracycline and taxane-pretreated MBC, there was no improvement in progression-free survival (the primary study endpoint) or overall survival.30

Ixabepilone Alone or in Combination with Capecitabine

The epothilones bind to tubulin and stabilize microtubules similar to the taxanes, but are active in taxane-resistant cell lines.31,32 Ixabepilone is a semisynthetic analogue of epothilone B, a natural product derived from the myxobacterium Sorangium cellulosum. It is approved as a single agent in patients with anthracycline, taxane, and capecitabine-resistant disease, and in combination with capecitabine in patients with anthracycline and taxane-resistant disease. Patients were required to meet strict pretreatment and resistance definitions for inclusion in the trials. In addition, patients were not eligible if there was grade 2 or higher neuropathy.

The first trial that supported regulatory approval of ixabepilone evaluated it as monotherapy (40 mg/m2 IV over 3 hours every 3 weeks) in 126 women with anthracycline, taxane, and capecitabine-resistant disease. 33 Resistance was defined as disease progression during or within 8 weeks of the last dose of therapy for metastatic disease, recurrence within 6 months of the last dose of adjuvant or neoadjuvant anthracyclines and/or taxanes therapy, or recurrence after prior trastuzumab (in the 7% of patients who had HER2 overexpressing disease). The response rate by central radiographic review in 113 evaluable patients was 12.4% (95% confidence intervals [CI] 6.9, 19.9%), and the investigator-assessed response in 126 evaluable patients was 18.3% (95% CI 11.0, 26.1%). The most common grade 3–4 treatment-related adverse events occurring in at least 10% of patients included neutropenia (54%), sensory peripheral neuropathy (14%), and fatigue/asthenia (13%).

The second trial which supported the regulatory approval of ixabepilone was a phase III trial of ixabepilone (40 mg/m2 IV over 3 hours every 3 weeks) plus capecitabine (1000 mg/m2 BID days 1–14) compared with capecitabine alone (1250 mg/m2 BID on days 1–14) in 752 patients with MBC resistant to anthracyclines and taxanes (Table 2). 19,20 Anthracycline and taxane resistance was defined as tumor progression during treatment or within 4 months of last dose in the metastatic setting, or recurrence within 12 months in the neoadjuvant or adjuvant setting. All patients were required to have measurable disease. Median progression-free survival (PFS) based upon a central radiology review was significantly prolonged by the combination compared with capecitabine monotherapy (5.8 vs. 4.2 months, p<0.0001), the primary study endpoint. The combination was also associated with a significantly improved response rate (35% vs. 14%; P < .0001) but not overall survival (OS). Grade 3–4 adverse events occurring in at least 10% of patients were more common in the combination arm, including neutropenia (68% vs. 11%), sensory neuropathy (21% vs. 0%), and fatigue (16% vs. 4%). In addition, the toxic death rate was higher in the combination arm (3% vs. 1%). All deaths within 30 days of last dose in the combination arm were related to neutropenia, and the risk was greatest in those who had a baseline grade 2 or higher elevation in liver chemistries; 5 of 16 such patients (31%) died, compared with 7 of 353 patients (2%) with no or grade 1 liver dysfunction, leading to a study protocol amendment excluding those with grade 2 or higher liver dysfunction at baseline.

Table 2.

Selected randomized trials in patients with anthracycline- and taxane-pretreated metastatic breast cancer

| Author | Experimental vs. Standard Arm | No. | Prior Anthracycline/Taxane | Prior Chemotherapy for Metastases | Primary Trial Endpoint | Median/PFS (mo.) | Objective Response Rate | Median OS (mo.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thomas et al. [19] | Ixabepilone+Capecitabine vs. Capecitabine | 752 | 97%/97% | 92% | PFS | 5.8 vs. 4.2 HR 0.75 P=0.0003 |

35% vs. 14% P<0.001 |

12.9 vs. 11.1 |

| Sparano et al. [20] | Ixabepilone+Capecitabine vs. Capecitabine | 1221 | 100%/100% | 80% | OS | 6.2 vs. 4.4 HR 0.79 P=0.005 |

43% vs. 29% P<0.001 |

16.4 vs. 15.6 |

| Cortes et al. [37] | Eribulin vs. Physician’s Choice | 762 | 99%/99% | 100% | OS | 3.7 vs. 2.2 | 12% vs 7% P=0.002 |

13.1 vs. 10.6 HR 0.81 P=0.04 |

| Martin et al. [41] | Gemcitabine+vinorelbine vs. vinorelbine | 252 | 100%/100% | 82% | PFS | 6.0 vs. 4.0 HR 0.66, P=0.003 |

36% vs. 26% | 15.9 vs. 16.4 |

| O’Shaughnessy et al. [47] | Carboplatin/gemcitabine + iniparib vs. Carboplatin/gemcitabine + placebo | 519 | 72%/89% | 43% | PFS & OS | 5.1 vs. 4.1 | 34% vs. 30% | 11.8 vs. 11.1 |

| Keller et al. [56] | Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin vs. vinorelbine or mitomycin + vinblastine | 311 | 83%/100% | 96% | PFS | 2.9 vs. 2.5 | 10% vs. 12% | 10.4 vs. 9.0 |

Abbreviation: HR – hazard ratio (provided only when difference statistically significant); PFS – progression free survival; OS – overall survival

A second phase III study randomized 1221 patients with MBC to ixabepilone/capecitabine combination with capecitabine alone using the same doses, schedules, and dose modification criteria as the prior trial (Table 2). 19,20 In contrast to the prior trial, the primary endpoint was OS (rather than PFS), patients with non-measurable or measurable disease were eligible (rather than measurable disease only); in addition, although anthracycline and taxane pretreatment were also required, patients were not required to have resistant disease. The study was powered to detect a 20% reduction in the hazard ratio for death, but failed to show a significant OS benefit in the primary unadjusted analysis (median 16.4 versus 15.6 months, hazard ratio [HR] 0.9; 95% CI 078–1.03; P= 0.12) There was a benefit for the combination in the pre-specified analysis after adjustment for baseline covariates (HR= 0.85 [95% CI: 0.75, 0.98], P = 0.023). Similar to the previous trial, the combination arm had significantly improved median PFS (6.2 versus 4.2 months, HR, 0.79; P=0.0005) and objective response rate (43% vs 29%, P=0.0001) in patients with measurable disease. The toxicity patterns were similar in this trial compared with the prior phase III trial, although fewer patients treated with the combination died during therapy (3% vs 7%) in this study; in addition, the rate of treatment-associated deaths were similar in the two arms (0.7% versus 0.3%), which was attributed to the excluding patients with hepatic dysfunction in this trial. A combined analysis of both trials indicated that patients with impaired performance status (Karnofsky performance status 70–80) derive greater clinical benefit for the combination and did not exhibit excessive toxicity.34

Eribulin

Eribulin mesylate is a non-taxane microtubule dynamic inhibitor. It is a structurally simplified synthetic derivative of halichondrin B, a natural product derived from the marine sponge Halichonria okidai. It has a novel mode of action causing tubulin sequestration into nonfunctional aggregates. This suppresses microtubule polymerization and causes irreversible mitotic block, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis, and is active in paclitaxel-resistant cell lines.35 The principal dose limiting toxicity in phase I trials was neutropenia.

After several phase II trials identified clinical activity for single agent eribulin in patients with anthracycline and taxane pretreated disease 36,37,38, a phase III trial compared eribulin (1.4 mg/m2 IV over 3–5 minutes on days 1–8 every 21 days) with physicians’ choice of therapy in 762 patients with locally recurrent or MBC who had received between 2 and 5 previous regimens that included an anthracycline and a taxane (Table 2). Patients were also required to have received at least two agents for advanced disease, and have disease progression within 6 months of their last chemotherapy regimen. In contrast to prior trials with ixabepilone, patients with grade 2 neuropathy were eligible. 13 Patients were randomly assigned 2:1 to eribulin or treatment of physician’s choice, a discretionary selection of any monotherapy, which included vinorelbine (25%), gemcitabine (19%), capecitabine (18%) taxanes (15%), anthracyclines (24%), or other cytotoxic agents (9%) or endocrine therapy (4%). The primary endpoint was achieved with significantly improved median OS in the eribulin arm (13.1 vs 10.7 months, HR 0.81, 95% CI, 0.66, 0.99, P=0.041). 13 For patients with measurable disease, the overall response rate by independent review was also significantly higher for eribulin (12% versus 5%, P=0.005), although median PFS was not significantly improved (3.7 versus 2.2 months, HR 0.87; 95% CI, 0.71, 1.05; P=0.14). Sensitivity analysis by predefined exploratory subgroups showed consistent results for improved OS favoring eribulin by disease subtype (estrogen and/or progesterone receptor positive; HER2- positive, and triple-negative), number of organs involved, sites of disease, and prior capecitabine. The overall frequency of adverse events and serious adverse events were similar between the two arms. In the eribulin group, neutropenia was the most frequently reported grade 3–4 adverse event (45%), but febrile neutropenia occurred in only 5%, and hematologic toxicities resulted in discontinuation in less than 1%. Peripheral neuropathy was the most common adverse event leading to discontinuation from eribulin (5%). For those who developed grade 3–4 sensory neuropathy but continued treatment due to clinical benefit, it improved to grade 2 or better in later cycles following delays and dose reductions. A recently completed phase III trial comparing eribulin with capecitabine failed to show prolongation in median PFS or OS, the primary trial endpoints. 39

Gemcitabine

Gemcitabine is a pyrimidine nucleoside analogue that inhibits DNA polymerization and RNA synthesis. 40 There has only be one phase III trials evaluated gemcitabine n patients with anthracycline and taxane pretreated disease (Table 2). The study included 252 women with locally recurrent or MBC pretreated with anthracyclines and taxanes and who were randomly assigned vinorelbine (30 mg/m2 IV on days 1 and 8 every 3 weeks) alone or in combination with gemcitabine (1200 mg/m2 IV on days 1 and 8 every 3 weeks). 41 Median PFS was significantly improved for the combination (6.0 versus 4.0 months, HR 0.66, 95% CI 0.50–0.88, P=0.003). There was a numerically higher response rate for the combination arm (36% vs. 26%, p=0.093), but no difference in OS (15.9 vs. 16.4 months). There was more grade 3–4 neutropenia (61% vs. 44%) and febrile neutropenia (11% vs. 6%) for the combination arm, but comparable non-hematologic toxicity.

Platinum analogues plus gemcitabine

Cisplatin and carboplatin are platinum complexes that binds preferentially to the N-7 position of guanine and adenine that produce DNA interstrand cross links. Carboplatin has a similar mechanism of action, although it requires a higher drug concentration and longer incubation time in vitro in order to produce a comparable effect. Both drugs undergo renal elimination. Relative to cisplatin, carboplatin produces less nausea and vomiting, nephrotoxicity, and neuropathy, but more thrombocytopenia and neutropenia.42 Both drugs are effective in patients with MBC associated with germline BCRA mutations.43 For unselected patients who largely have sporadic breast cancer, the platinum agents are also active when used as first line therapy, but are relatively ineffective when used as second line therapy.44,45 Two randomized trials evaluating the role of the poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitor iniparib provide some information about the efficacy of the carboplatin-gemcitabine combination in patients with anthracycline and taxane pretreated metastatic triple negative breast cancer (TNBC). The first was a randomized phase II trial including 116 patients receiving first or second-third line therapy which included carboplatin (AUC 2 IV) plus gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2 IV on days 1 and 8 every 3 weeks) alone or in combination with iniparib.46 The iniparib arm was associated with significantly higher response rate, median PFS, and overall survival, and thereby providing some information about the effectiveness of the carboplatin-gemcitabine combination in this population. A confirmatory phase III trial failed to show a benefit for the addition of iniparib to the same carboplatin/gemcitabine regimen in 519 patients with metastatic TNBC, of whom 222 (43%) received it as second or third-line therapy in patients who were largely anthracycline and taxane-pretreated. 47 The trial failed to meet its co-primary endpoints of improving PFS (median 5.1 vs. 4.1 months) and OS (11.8 vs. 11.1 months), and response rates were also similar in the two arms (34% vs. 30%) (Table 2). In addition, although iniparib was initially thought to exert its primary mechanism of action by inhibiting PARP, it was subsequently found to be a relatively weak PARP inhibitor, and induced its antitumor effects by inducing cell cycle arrest in the G2-M phase, promoting double strand DNA damage, and potentiatiating cell cycle arrest induced by carboplatin and gemcitabine. 47

Irinotecan

Irinotecan and its active metabolite, SN-38, interacts with cellular topoisomerase I–DNA complexes and has S-phase-specific cytotoxicity by preventing religation of the DNA strand, resulting in double-strand DNA breakage and cell death.48 A randomized phase II study in 103 patients with MBC who had progressive disease after one to three lines of chemotherapy compared irinotecan given IV in a 3 weekly (240 mg/m2 IV every 3 weeks) or weekly schedule (100 mg/m2 IV for 4 of 6 weeks). The weekly regimen was associated with more favorable response rate (23% vs. 14%) and median PFS (2.8 vs.1.9 months).49 A polymer-containing formulation of SN-38 (etirinotecan pegol) which produces sustained SN-38 blood levels has demonstrated activity in MBC.50 A phase III trial has been initiated comparing etirinotecan pegol (145 mg/m2 IV every 3 weeks) with physician’s choice of therapy in patients with MBC who have been previously treated with an anthracycline, taxane, and capecitabine (ClinicalTrials.Gov identifier NCT0149210).

Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin

Liposomes are closed vesicular structures initially described in the 1960’s that are capable of enveloping water-soluble molecules and may serve as a vehicle for delivering cytotoxic agents more specifically to tumor and limiting exposure of normal tissues.51 Current preparations of liposomes fall into two broad classes based upon their recognition by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS). One class of liposomes are readily recognized and phagocytised by the MPS due to binding of plasma proteins to the liposome surface, thereby inducing uptake by macrophages in the liver, spleen, lungs, and bone marrow, minimizing exposure of normal tissues, and thus diminishing some acute and chronic toxicities.52,53 A second class of agents includes liposomes that are designed to avoid detection by the MPS system. One example is pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD), which circulates in the plasma for a relatively long period compared with conventional doxorubicin and non-pegylated liposomal formulations. 54 The rationale for their development and use in breast cancer has been extensively reviewed.55

Of the three phase III trials evaluating PLD for MBC, two have included patients with anthracycline and/or taxane pretreated disease (Table 2). The first study included 301 patients who had disease progression following first or second-line taxane-containing regimen for metastatic disease. Patients were randomized to either PLD (50 mg/m2 every 4 weeks) or a comparator of physician’s choice, which included vinorelbine (30 mg/m2 weekly) in 85% or mitomycin C (10 mg/m2 day 1 and every 4 weeks) plus vinblastine (5 mg/m2 day 1, day 14, day 28, and day 42) every 6 to 8 weeks in the remainder.56 Results were similar between PLD and the comparator for PFS (median 2.9 versus 2.5 months) and OS (median 11.0 versus 9.0 months). The most frequently reported adverse events were nausea (23% vas. 31%), vomiting (17% vs. 20%), and fatigue (9% versus 20%) and were similar among treatment groups. PLD-treated patients experienced more HFS (37%; 18% grade 3, 1 patient grade 4) and stomatitis (22%; 5% grades 3–4). Neuropathy (11%), constipation (16%), and neutropenia (14%) were more common with vinorelbine. Alopecia was low in both the PLD and vinorelbine groups (3% and 5%). The second study compared docetaxel (75 mg/m2 IV every 3 weeks) alone or in combination with PLD (30 mg/m2 IV) in 751 patients with MBC who had relapsed at least one year after prior adjuvant doxorubicin-containing therapy.3 The combination arm was associated with significantly improved median TTP (median 9.8 vs. 7.0 months, HR=0.65; 95% CI 0.55–0.77, P=0.0001), which was the primary study endpoint. The combination was also associated with improved response rate (35% vs. 26%, P=0.009) but similar OS. Importantly, there was no excess cardiac toxicity in the PLD arm, providing proof of principle that PLD may be safety used after prior adjuvant anthracycline therapy. As in prior studies with PLD, the most common toxicities included HFS, stomatitis, and rash.

Conclusions

Anthracyclines and taxanes are effective cytotoxic agents that improve the potential for cure when used as adjuvant therapy, and prolong survival and palliate symptoms when used for the treatment of metastatic disease. Resistance invariably develops when used for metastatic disease, however, and contributes to recurrence in early stage disease. Several classes of cytotoxic agents produce response or disease stabilization in a modest proportion of patients who have progressive disease after prior anthracycline and taxane therapy, and have differing toxicity profiles. There are no predictive factors that are useful in guiding which agents to select for an individual patient. A systematic approach may be helpful in identifying which agents may be potentially used, which includes: (1) reviewing the patients prior antineoplastic drug history, (2) identifying comorbidities or residual toxicities from prior cytotoxic therapy that may limit the menu of potentially suitable agents, (3) identify agents for a history of resistance to the drug or class of agents, (4) determine whether there is an indication for concurrent administration with biologic therapy (eg, HER2 positive disease) or combination cytotoxic therapy (eg, rapidly progressive visceral disease). Fifth, if cytotoxic therapy alone is used, should it be used as a single agent, or in combination with other cytotoxic agents? Single cytotoxic agents should be suitable in most cases, although combination therapy may be considered in patients with rapidly progressive disease or high visceral tumor burden. The choice of a treatment regimen must be individualized based upon careful consideration of all of these factors.

Footnotes

Disclosure E. Andreopoulou: none; J.A. Sparano: consultant to Johnson & Johnson and Eisai; member of a speakers bureau for Bristol-Myers Squibb; and member of the data monitoring committee for Genenetech/Roche.

Contributor Information

Eleni Andreopoulou, Email: eandreop@montefiore.org, Assistant Professor Medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Department of Oncology, Section of Breast Medical Oncology, Montefiore Medical Center, 1825 Eastchester Road, 2South Rm 60, Bronx, New York 10461, Phone 718-904-2900, Fax 718-904-2890.

Joseph A. Sparano, Email: jsparano@montefiore.org, Professor Medicine of Medicine Women’s Health, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Department of Oncology, Chief, Section of Breast Medical Oncology, Montefiore Medical Center, 1825 Eastchester Road, 2South, Rm 48, Bronx, New York 10461, Phone 718-903-2555, Fax 718-904-2892.

References

Papers of particular interest have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Sparano JA, Wang M, Martino S, et al. Weekly paclitaxel in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2008;358:1663–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carrick S, Parker S, Thornton CE, Ghersi D, Simes J, Wilcken N. Single agent versus combination chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD003372. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003372.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3*.Sparano JA, Makhson AN, Semiglazov VF, et al. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin plus docetaxel significantly improves time to progression without additive cardiotoxicity compared with docetaxel monotherapy in patients with advanced breast cancer previously treated with neoadjuvant-adjuvant anthracycline therapy: results from a randomized phase III study. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:4522–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5013. Demonstrated cardiac safety for pegylated liposomal doxorubicin after prior exposure to adjuvant anthracycline therapy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan S, Friedrichs K, Noel D, et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus doxorubicin in patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2341–54. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sledge GW, Neuberg D, Bernardo P, et al. Phase III trial of doxorubicin, paclitaxel, and the combination of doxorubicin and paclitaxel as front-line chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer: an intergroup trial (E1193) J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:588–92. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6**.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. The New England journal of medicine. 2001;344:783–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101. Demonstrated that trastuzumab improves survival when added to chemotherapy as first line therapy for HER2/neu overexpression metastatic breast cancer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kardinal CG, Perry MC, Weinberg V, Wood W, Ginsberg S, Raju RN. Chemoendocrine therapy vs chemotherapy alone for advanced breast cancer in postmenopausal women: preliminary report of a randomized study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1983;3:365–71. doi: 10.1007/BF01807589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:220–41. doi: 10.3322/caac.21149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cardoso F, Di LA, Lohrisch C, Bernard C, Ferreira F, Piccart MJ. Second and subsequent lines of chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer: what did we learn in the last two decades? Ann Oncol. 2002;13:197–207. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Shaughnessy J. Extending survival with chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer. Oncologist. 2005;10 (Suppl 3):20–9. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-90003-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenberg PA, Hortobagyi GN, Smith TL, Ziegler LD, Frye DK, Buzdar AU. Long-term follow-up of patients with complete remission following combination chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2197–205. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.8.2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nabholtz JM, Senn HJ, Bezwoda WR, et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus mitomycin plus vinblastine in patients with metastatic breast cancer progressing despite previous anthracycline-containing chemotherapy. 304 Study Group. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1999;17:1413–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.5.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13**.Cortes J, O’Shaughnessy J, Loesch D, et al. Eribulin monotherapy versus treatment of physician’s choice in patients with metastatic breast cancer (EMBRACE): a phase 3 open-label randomised study. Lancet. 2011;377:914–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60070-6. Demonstrated that eribulin improved survival when comapred with physician’s choice of another monotherapy regimen in patients with extensively pretreated metastatic breast cancer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Shaughnessy J, Miles D, Vukelja S, et al. Superior survival with capecitabine plus docetaxel combination therapy in anthracycline-pretreated patients with advanced breast cancer: phase III trial results. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20:2812–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giordano SH, Buzdar AU, Smith TL, Kau SW, Yang Y, Hortobagyi GN. Is breast cancer survival improving? Cancer. 2004;100:44–52. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chia SK, Speers CH, D’Yachkova Y, et al. The impact of new chemotherapeutic and hormone agents on survival in a population-based cohort of women with metastatic breast cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:973–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dawood S, Broglio K, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Buzdar AU, Hortobagyi GN, Giordano SH. Trends in survival over the past two decades among white and black patients with newly diagnosed stage IV breast cancer. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:4891–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tevaarwerk AJ, Gray RJ, Schneider BP, et al. Survival in patients with metastatic recurrent breast cancer after adjuvant chemotherapy: Little evidence of improvement over the past 30 years. Cancer. 2012 doi: 10.1002/cncr.27819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas ES, Gomez HL, Li RK, et al. Ixabepilone plus capecitabine for metastatic breast cancer progressing after anthracycline and taxane treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5210–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.6557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20**.Sparano JA, Vrdoljak E, Rixe O, et al. Randomized phase III trial of ixabepilone plus capecitabine versus capecitabine in patients with metastatic breast cancer previously treated with an anthracycline and a taxane. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:3256–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.4244. Phase III trial which showed that the ixabepilone-capecitabine combination improved response and progression free survival compared with capecitabine alone in anthracycline and taxane-pretreated breast cancer, the combination did not improve survival. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21*.Pivot X, Asmar L, Buzdar AU, Valero V, Hortobagyi G. A unified definition of clinical anthracycline resistance breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:529–34. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.0958. Proposed definitions for anthracycine and taxane pretreatment versus resistance. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castiglione-Gertsch M, Tattersall M, Hacking A, et al. Retreating recurrent breast cancer with the same CMF-containing regimen used as adjuvant therapy. The International Breast Cancer Study Group. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:2321–5. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)10011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo X, Loibl S, Untch M, et al. Re-Challenging Taxanes in Recurrent Breast Cancer in Patients Treated with (Neo-)Adjuvant Taxane-Based Therapy. Breast Care (Basel) 2011;6:279–83. doi: 10.1159/000330946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Longley DB, Johnston PG. Molecular mechanisms of drug resistance. The Journal of pathology. 2005;205:275–92. doi: 10.1002/path.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fojo T, Coley HM. The role of efflux pumps in drug-resistant metastatic breast cancer: new insights and treatment strategies. Clin Breast Cancer. 2007;7:749–56. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2007.n.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geyer CE, Forster J, Lindquist D, et al. Lapatinib plus capecitabine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2733–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27**.Blum JL, Dieras V, Lo Russo PM, et al. Multicenter, Phase II study of capecitabine in taxane-pretreated metastatic breast carcinoma patients. Cancer. 2001;92:1759–68. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011001)92:7<1759::aid-cncr1691>3.0.co;2-a. Demonstrated efficacy for capecitabine monotherapy in anthracycline and taxane-pretreated metastatic breast cancer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bajetta E, Procopio G, Celio L, et al. Safety and efficacy of two different doses of capecitabine in the treatment of advanced breast cancer in older women. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2155–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Traina TA, Theodoulou M, Feigin K, et al. Phase I study of a novel capecitabine schedule based on the Norton-Simon mathematical model in patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1797–802. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.8388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller KD, Chap LI, Holmes FA, et al. Randomized phase III trial of capecitabine compared with bevacizumab plus capecitabine in patients with previously treated metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:792–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee FY, Borzilleri R, Fairchild CR, et al. BMS-247550: a novel epothilone analog with a mode of action similar to paclitaxel but possessing superior antitumor efficacy. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1429–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goodin S, Kane MP, Rubin EH. Epothilones: mechanism of action and biologic activity. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2015–25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perez EA, Lerzo G, Pivot X, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Ixabepilone (BMS-247550) in a Phase II Study of Patients With Advanced Breast Cancer Resistant to an Anthracycline, a Taxane, and Capecitabine. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3407–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.3849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34*.Roche H, Conte P, Perez EA, et al. Ixabepilone plus capecitabine in metastatic breast cancer patients with reduced performance status previously treated with anthracyclines and taxanes: a pooled analysis by performance status of efficacy and safety data from 2 phase III studies. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2011;125:755–65. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1251-y. Pooled analysis of 2 phase III trials indicating a survival benefit for the ixabepilone-capecitabine combination compared with capecitabine alone in patients with a Karnofsky performance status of 70–80, but not 90–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Towle MJ, Salvato KA, Wels BF, et al. Eribulin induces irreversible mitotic blockade: implications of cell-based pharmacodynamics for in vivo efficacy under intermittent dosing conditions. Cancer Res. 2011;71:496–505. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vahdat LT, Pruitt B, Fabian CJ, et al. Phase II study of eribulin mesylate, a halichondrin B analog, in patients with metastatic breast cancer previously treated with an anthracycline and a taxane. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2954–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cortes J, Vahdat L, Blum JL, et al. Phase II study of the halichondrin B analog eribulin mesylate in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer previously treated with an anthracycline, a taxane, and capecitabine. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3922–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.8467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aogi K, Iwata H, Masuda N, et al. A phase II study of eribulin in Japanese patients with heavily pretreated metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1441–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eribulin301. 2012 http://www.eisai.com/news/enews201244pdf.pdf.

- 40.Plunkett W, Huang P, Xu YZ, Heinemann V, Grunewald R, Gandhi V. Gemcitabine: metabolism, mechanisms of action, and self-potentiation. Semin Oncol. 1995;22:3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martin M, Ruiz A, Munoz M, et al. Gemcitabine plus vinorelbine versus vinorelbine monotherapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer previously treated with anthracyclines and taxanes: final results of the phase III Spanish Breast Cancer Research Group (GEICAM) trial. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:219–25. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Go RS, Adjei AA. Review of the comparative pharmacology and clinical activity of cisplatin and carboplatin. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:409–22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Narod SA. BRCA mutations in the management of breast cancer: the state of the art. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7:702–7. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Decatris MP, Sundar S, O’Byrne KJ. Platinum-based chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer: current status. Cancer Treat Rev. 2004;30:53–81. doi: 10.1016/S0305-7372(03)00139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carrick S, Ghersi D, Wilcken N, Simes J. Platinum containing regimens for metastatic breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004:CD003374. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003374.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O’Shaughnessy J, Osborne C, Pippen JE, et al. Iniparib plus chemotherapy in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:205–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ledford H. Drug candidates derailed in case of mistaken identity. Nature. 2012;483:519. doi: 10.1038/483519a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu LF, Desai SD, Li TK, Mao Y, Sun M, Sim SP. Mechanism of action of camptothecin. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;922:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb07020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49*.Perez EA, Hillman DW, Mailliard JA, et al. Randomized phase II study of two irinotecan schedules for patients with metastatic breast cancer refractory to an anthracycline, a taxane, or both. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2849–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.047. Demonstrated efficacy of irinotecan in patients with extenstively pretreated metastatic breast cancer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gale S, Croasdell G. 28th Annual JPMorgan Healthcare Conference--Exelixis and Nektar Therapeutics. IDrugs. 2010;13:139–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bangham AD, Horne RW. Negative Staining of Phospholipids and Their Structural Modification by Surface-Active Agents as Observed in the Electron Microscope. J Mol Biol. 1964;8:660–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(64)80115-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kanter PM, Bullard GA, Pilkiewicz FG, Mayer LD, Cullis PR, Pavelic ZP. Preclinical toxicology study of liposome encapsulated doxorubicin (TLC D-99): comparison with doxorubicin and empty liposomes in mice and dogs. In Vivo. 1993;7:85–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kanter PM, Bullard GA, Ginsberg RA, et al. Comparison of the cardiotoxic effects of liposomal doxorubicin (TLC D-99) versus free doxorubicin in beagle dogs. In Vivo. 1993;7:17–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gabizon A, Shmeeda H, Barenholz Y. Pharmacokinetics of pegylated liposomal Doxorubicin: review of animal and human studies. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:419–36. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Robert NJ, Vogel CL, Henderson IC, et al. The role of the liposomal anthracyclines and other systemic therapies in the management of advanced breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2004;31:106–46. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Keller AM, Mennel RG, Georgoulias VA, et al. Randomized phase III trial of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin versus vinorelbine or mitomycin C plus vinblastine in women with taxane-refractory advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3893–901. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]