ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Typically, chronic disease self-management happens in a family context, and for African American adults living with diabetes, family seems to matter in self-management processes. Many qualitative studies describe family diabetes interactions from the perspective of adults living with diabetes, but we have not heard from family members.

OBJECTIVE

To explore patient and family perspectives on family interactions around diabetes.

DESIGN

Qualitative study using focus group methodology.

PARTICIPANTS & APPROACH

We conducted eight audiotaped focus groups among African Americans (four with patients with diabetes and four with family members not diagnosed with diabetes), with a focus on topics of family communication, conflict, and support. The digital files were transcribed verbatim, coded, and analyzed using qualitative data analysis software. Directed content analysis and grounded theory approaches guided the interpretation of code summaries.

RESULTS

Focus groups included 67 participants (81 % female, mean age 64 years). Family members primarily included spouses, siblings, and adult children/grandchildren. For patients with diabetes, central issues included shifting family roles to accommodate diabetes and conflicts stemming from family advice-giving. Family members described discomfort with the perceived need to police or “stand over” the diabetic family member, not wanting to “throw diabetes in their [relative’s] face,” perceiving their communications as unhelpful, and confusion about their role in diabetes care. These concepts generated an emergent theme of “family diabetes silence.”

CONCLUSION

Diabetes silence, role adjustments, and conflict appear to be important aspects to address in family-centered diabetes self-management interventions. Contextual data gathered through formative research can inform such family-centered intervention development.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2230-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: family interactions, type 2 diabetes, qualitative research, African Americans

INTRODUCTION

African Americans have some of the highest rates of diabetes and obesity.1,2 Over the last two decades, diabetes prevalence has increased significantly among adult non-Hispanic blacks3 to a level that is nearly double that of non-Hispanic whites. Fueling some of this increase are the high rates of obesity among African Americans, particularly among women. Today, about one in two African American women is classified as obese, compared to the national rate of about one in three.2 This context of high diabetes and obesity prevalence among African Americans challenges researchers to identify treatment approaches and interventions to prevent secondary complications.

Sufficient research already exists demonstrating the effectiveness of lifestyle and self-management interventions in the treatment of overweight/obesity and diabetes.4–6 In the management of diabetes, there is evidence of proven effectiveness of family-based interventions for families of children with diabetes.7 Studies show that family interactions among adults with diabetes also affect diabetes self-management.8–10 Moreover, recent studies show aspects of family functioning can influence weight loss success among African Americans.11

This evidence has raised interest in intervention research focused on the behaviors and interactions of adults in families living with diabetes.12–14 In the case of African American adults living with diabetes, qualitative studies with patients have described family members’ influence on diabetes self-management.15–17 While these qualitative studies have focused on family roles and interactions from the perspective of persons with diabetes, little to no attention has been given to understanding the views of non-diabetic family members (not just limited to spouses) who live or regularly interact with diabetic family members. By exploring family diabetes interactions from the perspective of adult family members not diagnosed with diabetes, we potentially gain a broader view of the interactions that may impact diabetes management in African American families. Moreover, understanding the interactions of family members who are themselves at risk for diabetes could provide important information about family-centered approaches to diabetes prevention.

With a focus on designing a family-based behavioral lifestyle intervention for overweight/obese African Americans with diabetes that would address both diabetes self-management and diabetes prevention (for family members), we conducted this formative research to guide intervention development. To this end, we conducted qualitative research to gather information from adults living with type 2 diabetes and family members not diagnosed with diabetes. Hearing from both family members and patients on issues such as family communication, conflict, and support would offer a unique opportunity to expand our understanding of how African American families interact in diabetes management. Also important was exploring how diabetes changes family life and family members’ reactions to these changes. We pursued both lines of inquiry to gain valuable information for developing family-focused intervention components.

PARTICIPANTS, DESIGN, AND APPROACH

Participants

Study participants included adults who self-described as African American. The study recruited adults with diagnosed diabetes and family members in regular contact or living with someone with type 2 diabetes. These two sets of participants were recruited separately, such that family member participants were not necessarily related to participants with diabetes. Persons with diabetes were eligible if they: 1) were 21 years of age or older; 2) self-reported a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and were currently under the care of a physician or other health care provider; 3) self-reported as being overweight/obese (BMI ≥ 27); and 4) spoke English. Persons with diabetes who lived alone and had no regular interactions with family members were ineligible. Inclusion criteria for family members were: 1) 21 years of age or older; 2) not diagnosed with type 2 diabetes; 3) living with or married to (≥ 1 year) an African American adult diagnosed with diabetes or in regular contact with an African American with diabetes self-described as a blood relative; 4) self-reported overweight/obesity (BMI ≥ 27); and 5) English-speaking.

Design and Approach

This study used focus group methodology. Participants were identified by four community recruiters who were well respected in their communities and had previously worked with the research team. We asked each recruiter to recruit one to two groups of 8–12 persons per group. Using recruitment flyers and information about eligibility criteria, recruiters collected names and phone contact information from potential participants. Study staff then made all follow-up contacts. The recruiters also identified community sites in which to hold the focus group(s), and scheduled groups based on convenient times for participants. Recruiters received a small stipend, and each site representative received minor reimbursement for costs associated with making the space available. The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board approved protocols for recruitment and conduct of the focus groups.

Data Collection and Analysis

We conducted eight 90-min focus groups (four among persons with diabetes and four among family members) between February and April 2008. Participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire and provided written informed consent before each group. Each participant received a $20 cash incentive and standard (American Diabetes Association, National Diabetes Education Program) materials on diabetes self-management or prevention.

All groups were moderated and audiotaped by a trained and experienced African American moderator (CSH). Questions and probes elicited descriptions of family interactions, with a particular focus on communication, conflict, and support (see sample questions in Appendix 1, available online). In developing the moderator’s guide, we reviewed family and diabetes research8,10,12–17 to identify family factors related to diabetes self-management. Digital files were transcribed verbatim and uploaded to Atlas.ti (Scientific Software Development, Berlin), a software program that facilitates qualitative data analysis.

We created a code dictionary (codes with definitions) for each type of focus group (family members and persons with diabetes). To refine our coding system, two reviewers first coded one transcript, using this exercise to add and revise codes. All transcripts were then independently coded by two to three coders who were either African American (CSH, CT, CC), medical providers caring for patients with diabetes (CC, LC), or family members of persons with diabetes (CC, CT). Coding discrepancies were resolved through consensus. Using summary documents (code frequency tables and quotation summaries) created for each set of transcripts, we met to discuss quote interpretation, group codes into themes, and compare thematic content within and across focus groups.

Because the purpose of this research was to inform intervention design and not to develop theory, our analytic approach relied primarily on directed content analysis, in which we derived initial codes from existing research that guided development of the discussion guide.18 We also used an inductive approach consistent with conventional content analysis and grounded theory, using the focus group data to guide interpretation and description of emergent themes. Qualitative researchers often use triangulation to enhance the trustworthiness or credibility of a study’s interpretation and findings, gathering multiple perspectives to reduce the risk of systematic bias.19 We relied primarily on triangulating multiple researcher perspectives and theories during analysis and interpretation.

RESULTS

A total of 67 African American adults (35 persons with diabetes and 32 family members) participated in eight focus groups, comprised of 3–12 participants. Seven focus groups were held in church fellowship halls and one in the private residence of a community member. Table 1 shows the characteristics of each set of focus group participants. Participants with diabetes were on average 65 years of age and diagnosed for 8 years, with most (49 %) treated with oral hypoglycemic agents only. Family members were on average 62 years of age and included mostly spouses, siblings, and adult children or grandchildren. Most (56 %) reported providing three to four types of support to their diabetic family members.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Persons with diabetes (N = 35) | Family members (N = 32) | |

|---|---|---|

| N (%)* | N (%)* | |

| Age, mean (SE), y | 64.8 (2.80) | 62.2 (2.47) |

| Gender, Female, % | 28 (80) | 26 (81) |

| Educational attainment, mean (SE), y | 12.2 (0.40) | 12.2 (0.37) |

| Employed | 10 (29) | 11 (34) |

| Household income (annual)*: | ||

| < $30,000 | 14 (58) | 13 (45) |

| $30,000–< $50,000 | 7 (29) | 8 (28) |

| ≥ $50,000 | 3 (13) | 8 (28) |

| Persons with diabetes | ||

| Years diagnosed, mean (SE), y | 8.2 (1.24) | |

| Treatment: | 17 (49) | |

| Oral hypoglycemic agent(s) only | 15 (43) | |

| Insulin (± oral hypoglycemic agent(s)) No diabetes medication | 3 (9) | |

| Perceived blood glucose control, mean (SE)† | 3.4 (0.19) | |

| Adult family members in household: (N = 34) 1 or more | 24 (71) | |

| Children (< 18 years of age) in household: 1 or more | 8 (24) | |

| Family members | ||

| Relationship to person with diabetes‡: | ||

| Spouse | 8 (25) | |

| Sibling | 7 (22) | |

| Child/Grandchild | 10 (31) | |

| Other | 14 (44) | |

| Type of support given to person with diabetes‡: | ||

| Diabetes medication(s) | 14 (44) | |

| Doctor’s visits | 15 (47) | |

| Food/Meals | 20 (63) | |

| Diabetes information | 14 (44) | |

| Emotional/coping | 16 (50) | |

| Other diabetes care | 11 (34) | |

| Number of support types provided: | ||

| 1–2 | 8 (25) | |

| 3–4 | 18 (56) | |

| 5–6 | 6 (19) | |

*Data are n (%) unless otherwise indicated. Sum of percentages may not = 100 due to rounding. Missing data for household income: persons with diabetes, N = 24 (missing = 11); family members, N = 29, (missing = 2)

†Scale (analog) of 1 = not very good to 5 = very good control

‡Multiple responses allowed if regular contact with more than one family member with diabetes

Codes and Concepts—Persons with Diabetes

The main concepts from the persons with diabetes groups centered around diabetes’ impact on individuals, family roles, and family conflict (Table 2). These concepts are described below, along with representative quotes.

Table 2.

Summary of Codes and Concepts from Focus Groups Among Persons with Diabetes and Family Members

| Code category | Concepts |

|---|---|

| Persons with diabetes | |

| Diabetes impact | Diabetes as ‘expected’ and the norm, with no place to talk about diabetes |

| Diabetes-related role changes | Shifting roles and role reversals within families |

| Diabetes-related conflict | Family conflicts as misdirected attempts by family to be helpful |

| Family members | |

| Diabetes interactions | Food policing, ‘standing over’ and watching person with diabetes |

| Diabetes-related conflict | Role conflict and confusion |

| Family balance | Not wanting to ‘throw diabetes in their face’ |

| Family needs | Need for family diabetes education |

| Diabetes communication | Talking doesn’t help |

No Place to Talk About Diabetes

Participants described diabetes as an expected condition for African Americans. According to this view, because African American families expect that they will have to “deal with” diabetes, it has become a common background condition that is not worth talking about relative to other problems, stressors, and challenges. According to one participant, “It’s always something…so you just go on with it.”

“You know diabetes has been in us [as a race]… And then things would happen, it’s like poor circulation, you’d lose a leg…you just took care of it and went on. It was not like you would call [someone] and say, ‘How you doing today?’ You know how people say ‘Well, I called her, and she went to complaining about what was wrong. I don’t want to call her ‘cause I don’t want to hear that. I’m already stressed myself.’”

Shifting Family Roles and Role Reversals

Diabetes affects the family life of persons with diabetes by changing family roles. Discussions highlighted what happens when, for example, adult children take on the role of telling parents what they should be doing to take care of their diabetes, or when a spouse assumes the decision-making role for what and how foods are prepared for the person with diabetes. Participants also commented that roles change when traditional roles (especially food preparation) are seen as inconsistent with diabetes self-management. Having to change or make a shift in these roles may be accompanied by guilt.

“It’s good. I don’t complain. Sometimes I don’t want to eat what she cooks. I am like a child.”

“A lot of time I feel guilty if I don’t cook. I just like to cook sweets. So I just make a cake or something, and I end up eating a piece…most of it by myself. I’m not giving them some of the things like all the cake and stuff…I don’t need it, but I feel guilty.”

Diabetes Family Conflict

Conflicts between family members and the person with diabetes seem to revolve around uninvited and/or unwelcome advice-giving. Diabetic participants described family members telling them what to do (especially what they can and cannot eat), doing things for them that they can do for themselves, or being overprotective. Although indicating that they understood that family members were trying to help, these situations often appeared to leave the person with diabetes feeling powerless to make their own decisions.

“I think it depends on what level you’re at. If you are doing well, nothing particular bothering you, then they don’t take it serious. But if you get down and they think you will really get sick or something, that’s when they come in and want to be the doctor and tell you what to do.”

Codes and Concepts—Family Members

In the groups with family members, discussions centered on food policing, conflict and confusion about their role, attempts to not always focus on diabetes, needing to know more about diabetes, and family diabetes communication (Table 2).

Food Policing

Family members reported feeling the need to monitor the self-management behaviors of their family members living with diabetes. However, simply “standing over” or “watching” the behaviors of another adult appeared to be an uncomfortable position. Much family monitoring dealt with food-related behaviors, but it also included blood glucose self-testing.

“It’s just hard to deal with him because it’s like he’s in denial. I ask him all the time ‘Did you test your sugar?’ and he’d say ‘Yeah, it’s OK.’ It’s like he does not share information and I don’t want to stand over him. I don’t want to watch him, but I worry that it’s not under control.”

Role Conflict and Confusion

The conflict and confusion expressed by family members was in the form of questioning whose role it was to tell the patient with diabetes how to take care of their diabetes. Many expressed conflicts between their role as a spouse, child, or sibling, and the perceived need to help their relatives with diabetes take better care of themselves. Some expressed confusion about their role, and questioned whether they should be giving diabetes advice that might conflict with advice from doctors or other providers. Role confusion made decisions about what to do more difficult and sometimes resulted in unintended family conflict.

“I’m the wife, not the mother… He was under control and baking cakes every weekend. It didn’t go to the back of our minds that he was a diabetic, but we just let it go…because he said, ‘It’s under control.’ He is checking [his blood sugar], but it’s not like he’s sharing that information with me, and I get tired of nagging.”

Throwing Diabetes in Their Faces

One area of great difficulty mentioned by family members of adults with diabetes is the conflict that arises when family members want the person with diabetes to do a better job of self-management, but perceive it as cruel to “throw diabetes in their face” by reminding them of diabetes complications. This seemed to be especially true in families where diabetes was prevalent; in such cases, individuals with diabetes live with the fear of complications and memories of how diabetes has devastated their family. These views make it hard to communicate concerns about self-management behaviors. Other family members spoke of wanting balance, such that diabetes does not take over every aspect of family life and the person with diabetes does not feel “sick” all the time. The desire for balance may mean that diabetes is set aside at social events involving food, so that the person can have time away from diabetes. Additionally, some participants stated that foods brought into the home should not be selected based solely on the needs of the person with diabetes.

“I don’t have to remind him but, you know, his mother was a diabetic and she’s deceased and his brother was diabetic and he’s deceased. His mother, she went blind, and his brother lost a limb. And so you know…I know these things he goes through. I don’t throw it in his face because he knows it. I say, ‘You have to take care of yourself.’”

Need for Family Diabetes Education

Family members who want to support relatives with diabetes reported that they don’t know how to help provide information about diabetes self-management. They mentioned not knowing how to interpret when a family member was feeling badly (not knowing when it was/was not related to diabetes) or what information to give, especially about diet.

Talking Doesn’t Seem to Help

Many family members reported feeling compelled to say something when their relative was not caring well for their diabetes. They suggested, however, that well-meaning words either had no impact or had unintended negative consequences. Many felt torn between not saying anything (so as not to “nag”), and wanting to say something to show that they care. The prevailing view was that talking did not help, but they didn’t know what else to do.

“It’s just negative, now that I think about it. He doesn’t care for it. It gets on his nerves. He knows I’m trying to help, but it doesn’t benefit him.”

Themes and Relational Interpretations

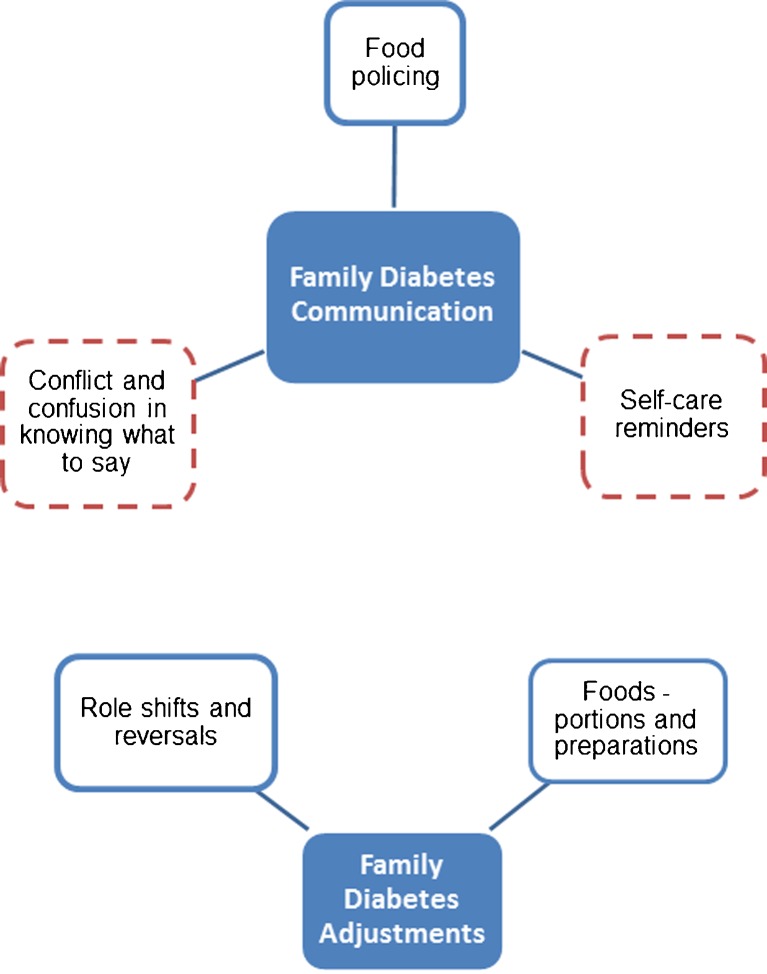

Combining the perspectives of family members and persons living with diabetes resulted in two major themes: family diabetes communication and family adjustments. Figure 1 shows the relationship of discussion concepts to these themes. Family diabetes communications from both patient and family member perspectives mainly revolve around food policing or communications described by family members as self-management reminders. The category of communication conflict and confusion captures the concepts described earlier, namely “throwing diabetes in their face,” not knowing what to say, needing diabetes education, role confusion, conflict arising from diabetes communication, and the feeling that “talking doesn’t seem to help.”

Figure 1.

Family diabetes communications and adjustments. * Communication concepts from both focus groups; solid border = both groups; dashed = family members only.

Both sets of participants suggested that families make two types of adjustments to living with diabetes: adjustments related to family roles, and adjustments related to the family food environment (Fig. 1). In the family roles category, persons with diabetes discussed giving up traditional roles and accepting new roles assumed by family members (e.g., adult children and spouses giving advice and making decisions about food). For family members, role changes had to do with trying to help the relative with diabetes. Contributing to the food-specific adjustments was the concept of “balance” mentioned by some family members.

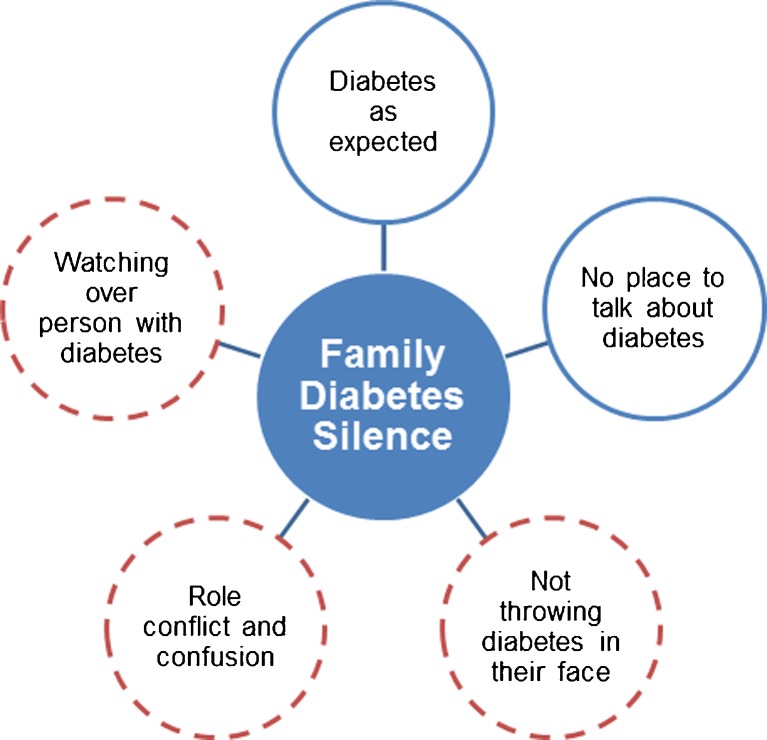

Emerging from the combined perspectives of both sets of focus group participants is the theme of “family diabetes silence” (Fig. 2). Given the high prevalence of diabetes, both family members and patients with diabetes described diabetes as an expected “background” condition that did not warrant frequent discussion relative to other daily challenges or life events. The theme of “diabetes silence” also emerged from family members’ comments about being concerned but not knowing what to say, feeling conflicted or confused about their role in diabetes care, or not wanting to mention diabetes for fear of eliciting negative thoughts and feelings about living with diabetes. All of these issues lead to family members remaining silent about diabetes, even though there are things they want to communicate (in words) to the family member living with diabetes.

Figure 2.

Contributors to family diabetes 'silence' theme. * Concepts from both groups contributing to family diabetes silence; solid border = both groups; dashed = family members only.

DISCUSSION

This qualitative study of African American families living with diabetes provides two perspectives on interactions between persons living with diabetes and their family members. When both perspectives are combined, the emergent themes of family diabetes ‘silence’ and ‘adjustments’ offer new ways of conceptualizing the behavioral context for diabetes management in African American families. Family diabetes silence, in particular, presents a complex and interesting view of how issues related to communication, conflict, roles, and support are connected to create a behavioral environment that undoubtedly impacts diabetes self-management. The purpose of this formative research was to inform the design of a behavioral lifestyle intervention for African American adults living with diabetes. Our findings provide culturally relevant information that helps to identify important intervention components, especially when integrated with what’s already known about family-based interventions for chronic disease management12,20,21 and family diabetes interactions.14,22–25 Designing a behavioral lifestyle intervention for African American families living with diabetes based on these findings suggests the following:

Enhance communication and conflict management skills – The theme of family diabetes silence revolved mainly around issues of communication and conflict. Thus, enhancing family communication skills could potentially prevent some conflicts affecting family interactions and, ultimately, family diabetes management. Improving communication skills would also mean including opportunities for intervention participants to learn and practice active listening. Addressing conflict directly, although challenging, might include strategies for managing emotions (and stress) and problem-solving training. The contributors to family diabetes silence shown in Figure 2 could be used as discussion prompts, adding meaningful context to skill-building activities. Better communication skills may be essential to improve family members’ ability to offer effective support to relatives with diabetes. Our results suggest that unhelpful words and silence can have equally harmful consequences.

Strengthen family support mechanisms – Family members want to support relatives with diabetes but sometimes don’t know what to do or say. Likewise, persons living with diabetes may not clearly communicate the support they desire. To achieve effective support, family-focused interventions may need to strengthen diabetic individuals’ ability to enlist family support that improves disease management while upholding autonomy (an important part of feeling motivated to engage in chronic disease management).26,27

Clarify roles for family members – For family members to play a more productive role in supporting diabetes management, they may need to know what role(s) they should play, and what adjustments to previous roles may be needed. In the context of an intervention, discussions of family roles can be integrated in topics related to communication, support, and conflict or stress management. Additionally, focusing on what roles family members can play by engaging in healthful lifestyle behaviors (and not just in what they say), may be another approach to more productive family interactions that support diabetes management.

To operationalize these behavioral strategies, it may be necessary to collaborate with experts in psychology and family and marital system dynamics. Such expertise should lead to appropriately designed family-focused interventions that fit the context of African American families living with diabetes. Because our findings provide culturally relevant “stories” that are likely to be familiar to African Americans, our formative research can frame and contribute to this collaborative process of developing family-focused diabetes interventions. Beyond the value to intervention design, these findings also have implications for health care providers. It may be important for providers to talk with patients about the nature of family interactions around diabetes and move beyond simple inquiries about the presence or absence of family support. Family members may also need additional information that helps them understand their role in supporting the patient with diabetes.

Although we’ve described the value of this qualitative research, some limitations should be noted. The study’s convenience sample of older, lower-socioeconomic-status African Americans living in the south means our findings cannot be generalized to all African Americans living with diabetes. Additionally, we focused on family members without diabetes, which limits the extent to which these data can inform intervention designs focused on interactions between family members who both live with diabetes. These data are best used to further our understanding of diabetes self-management in African American family contexts so that we can translate that understanding into effective family-focused interventions.

CONCLUSION

This qualitative study with a relatively large sample of African Americans took a novel approach of focusing on the views of family diabetes interactions held by adult family members not diagnosed with diabetes, while also gathering perceptions from patients living with diabetes. The emergent theme of “family diabetes silence” broadens our contextual understanding of factors that shape family diabetes interactions and potentially influence the behaviors of persons living with diabetes. This formative research provides important guidance to inform the design of family-based interventions for adult African Americans with type 2 diabetes. Designing intervention components that address family diabetes silence, role adjustments, and conflict offer potentially new approaches to facilitate improvements in diabetes self-management. Additionally, our findings expand what we currently know of the family diabetes context, thus filling a gap in African American family-focused diabetes research. The important contribution of this research to the existing literature lies in exposing the perspectives of family members in their interactions with diabetes self-management. This exposure creates opportunities for informing new intervention approaches to address both risk reduction and enhanced diabetes self-management support in African American families living with diabetes.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOC 51 kb)

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant K01DK080079. Dr. Cené’s work on this project was supported by award number KL2RR025746 from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. We are indebted to the community recruiters and participants from Durham, Raleigh, Siler City, Magnolia, and Fuquay Varina, NC who took the time to share their views of families living with diabetes. The authors also acknowledge the editorial assistance of Dr. Claire Viadro.

A portion of this study was presented in oral abstract form at the International Society for Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity annual meeting in Melbourne, Australia, 15–18 June, 2011.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Fact Sheet: national estimates and general information on diabetes and prediabetes in the United States, 2011. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011. Available at: http://diabetes.niddk.nih.gov/dm/pubs/statistics/#Diagnosed20. Accessed 3 September 2012.

- 2.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cowie CC, Rust KF, Ford ES, et al. Full accounting of diabetes and pre-diabetes in the US population in 1988–1994 and 2005–2006. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:287–294. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wadden TA, Butryn ML, Wilson C. Lifestyle modification for the management of obesity. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2226–2238. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of typ 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wadden TA, West DS, Neiberg R, et al. One-year weight losses in the Look AHEAD Study: factors associated with success. Obesity. 2009;17:713–722. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armour TA, Norris SL, Jack L, Jr, et al. The effectiveness of family interventions in people with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Diabetes Med. 2004;22:1295–1305. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chesla CA, Fisher L, Mullan JT, et al. Family and disease management in African-American patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2850–2855. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.12.2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fisher L, Chesla CA, Bartz RJ, et al. The family and type 2 diabetes: a framework for intervention. Diabetes Educ. 1998;24:599–607. doi: 10.1177/014572179802400504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bell RA, Summerson JH, Konen JC. Racial differences in psychosocial variables among adults with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Behav Med. 1995;21:69–73. doi: 10.1080/08964289.1995.9933745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samuel-Hodge CD, Gizlice Z, Cai J, Brantley PJ, Ard JD, Svetkey LP. Family functioning and weight loss in a sample of African Americans and whites. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40:294–301. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9219-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosland AM, Piette JD. Emerging models for mobilizing family support for chronic disease management: a structured review. Chronic Illn. 2010;6:7–21. doi: 10.1177/1742395309352254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cole I, Chesla CA. Interventions for the family with diabetes. Nurs Clin N Am. 2006;41:625–639. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosland AM, Heisler M, Choi HJ, Silveira MJ, Piette JD. Family influences on self-management among functionally independent adults with diabetes or heart failure: do family members hinder as much as they help? Chronic Illn. 2010;6:22–33. doi: 10.1177/1742395309354608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samuel-Hodge CD, Headen SW, Skelly AH, et al. Influences on day-to-day self-management of type 2 diabetes among African-American women” spirituality, the multi-caregiver role, and other social context factors. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:928–933. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carter-Edwards L, Skelly AH, Cagle CS, et al. “They care but don’t understand”: family support of African American women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2004;30:493–501. doi: 10.1177/014572170403000321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones RA, Utz SW, Williams IC, et al. Family interactions among African Americans diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2008;34:318–326. doi: 10.1177/0145721708314485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guidelines for Critical Review Form: Qualitative Studies (Version 2.0) by Letts L, Wilkins S, Law M, Stewart D, Bosch J, & Westmorland M, 2007. Available at: http://www.srs-mcmaster.ca/Portals/20/pdf/ebp/qualguidelines_version2.0.pdf. Accessed 3 September 2012.

- 20.Hartmann M, Bazner E, Wild B, Eisler I, Herzog W. Effects of interventions involving the family in the treatment of adult patients with chronic diseases: a meta-analysis. Psychother Psychosom. 2010;79:136–148. doi: 10.1159/000286958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martire LM, Lustig AP, Schulz R, Miller GE, Helgeson VS. It is beneficial to involve a family member? A meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for chronic illness. Health Psychol. 2004;23:599–611. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.6.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samuel-Hodge CD, Skelly AH, Headen S, Carter-Edwards L. Familial roles of older African-American women with type 2 diabetes: testing of a new multiple caregiving measure. Ethn Dis. 2005;15:436–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher L, Chesla CA, Skaff MM, Mullan JT, Kanter RA. Depression and anxiety among partners of European-American and Latino patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1564–1570. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.9.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fisher L, Chesla CA, Skaff MM, et al. The family and disease management in Hispanic and European-American patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:267–272. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosland AM, Kieffer E, Isreal B, et al. When is social support important? The association of family support and professional support with specific diabetes self-management behaviors. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1992–1999. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0814-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams GC, McGregor HA, Zeldman A, Freedman ZR, Deci EL. Testing a self-determination theory process model for promoting glycemic control through diabetes self-management. Health Psychol. 2004;23:58–66. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams GC, Patrick H, Niemiec CP, et al. Reducing the health risks of diabetes: how self-determination theory may help improve medication adherence and quality of life. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35:484–492. doi: 10.1177/0145721709333856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC 51 kb)