Abstract

Purpose

Teenage girls in low-income urban settings are at elevated risk for HIV, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and unintended pregnancies. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of a sexual risk-reduction intervention, supplemented with post-intervention booster sessions, targeting low-income, urban, sexually active teenage girls.

Method

Randomized controlled trial in which sexually-active urban adolescent girls (n=738) recruited in a mid-size, northeastern U. S. city were randomized to a theory-based, sexual risk reduction intervention or to a structurally-equivalent health promotion control group. Assessments and behavioral data were collected using ACASI at baseline, then at 3, 6 and 12-months post-intervention. Both interventions included four small group sessions and two booster sessions.

Results

Relative to girls in the control group, girls reciving the sexual risk-reduction intervention were more likely to be sexually abstinent; if sexually active, they showed decreases in (a) total episodes of vaginal sex at all followups, (b) number of unprotected vaginal sex acts at 3 and 12-months, and (c) total number of sex partners at 6 months. Medical record audits for girls recruited from a clinical setting (n=322) documented a 50% reduction in positive pregnancy tests at 12-months.

Conclusions

Theory-based, behavioral interventions tailored to adolescent girls can help to reduce sexual risk and may also reduce unintended pregnancies. Although sexually active at enrollment, many of the girls receiving the intervention were more likely to practice secondary abstinence. Continued refinement of sexual risk-reduction interventions for girls are needed to ensure they are feasible, appealing, and effective.

Keywords: Adolescent girls, HIV prevention, sexual risk, intervention, randomized controlled trial

INTRODUCTION

Many adolescents engage in sexually risky behaviors increasing their chances of acquiring HIV and STIs [1]. Recently, 39% of sexually active adolescents reported no condom use during last intercourse [2]. Nationally, more than 10% of girls, 15–19, reported intercourse with multiple partners [1]. Concurrency or brief intervals between partners was reported as common [3]. Teenage girls, particularly in low-income urban settings, are at elevated risk for HIV, STIs, and unintended pregnancies [4]. Among teens, nearly 90% heterosexually-acquired HIV cases occur in girls [5], and among the estimated 19-million cases of STIs occurring annually in the U.S. [6], girls 15–19 have the highest rates of gonorrhea and chlamydia relative to similarly-aged boys and women. African-American women and girls account for 57% of HIV infections among all U.S. women [7]. Because adolescents in low-income urban settings often become sexually active at early ages [8], targeted sexual risk-reduction interventions can help curb STIs and unintended pregnancies in vulnerable youth [9, 10].

Several teen interventions [9–12], grounded in social-cognitive models, including the Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills model [13], targeted adolescents, finding short-term risk reduction [14]. Encouraging findings were noted in a 6-session intervention targeting African-American teens recruited from community-based organizations in northeastern cities. Participants showed increases in condom use over 3, 6, and 12 month intervals compared to teens not receiving the intervention [11]. HIV-stigma is identified as a barrier to safer sexual activities especially among those belonging to racial or ethnic minorities [15]. In a skill-based intervention of 1654 African-American adolescents, HIV knowledge was shown to decrease stigma in teens[16]. Despite traditional sex roles and power imbalances observed in heterosexual relationships [17], few interventions are tailored specifically for adolescent girls [10].

Refinement of female-tailored interventions and promotion of the maintenance of intervention gains are needed. One such intervention was developed for African-American girls, 14–18, in a large southeastern city. Small groups attended four 4-hour weekly sessions in clinical settings. Increases in condom use, decreased pregnancy, and decreased new sex partners at 6 and 12-months were reported [10]. Subsequently, a chlamydia-prevention intervention targeting African-American girls, 15–21, with a diagnosis of STIs [18] consisted of: (a) two 4-hour meetings, (b) vouchers for partners for STI testing and treatment, and (c) four motivational phone calls over 12-months. At 12-months, fewer cases of chlamydia were noted, and girls reported more condom-protected sex acts and use at last intercourse.

Despite these positive findings, there is limited work addressing initiation of sexual risk-reduction activities in girls and long-term maintenance [19, 20]. Following initial intervention-loading dose, part of our tailoring included booster sessions to address behavioral patterns of girls that are expected to occur as they age. Girls often have multiple partners, brief relationships, and practice serial monogamy [1, 3] suggesting needs for boostering over time. Booster sessions, particularly with adults, can promote maintenance of gains observed with health-behavior interventions [21, 22]. Given the importance of long-term maintenance of behavior change, this strategy warrants further study.

The current study evaluated the efficacy of a sexual risk-reduction (SRR) intervention supplemented with booster sessions, with a sample of low-income, urban, sexually-active adolescent girls. We hypothesized that compared to girls in an attention-matched control condition, girls in the SRR intervention would reduce: total vaginal sex exposures, unprotected vaginal sex, and number of partners. With exploratory analyses, we examined whether the intervention would be associated with fewer unintended pregnancies.

METHODS

Participants

We recruited girls aged 15–19 who could participate in an English-speaking intervention. Eligibility to ensure an at-risk sample included: unmarried, not pregnant, not given birth within the past 3-months, and sexually active within the past 3-months. Table I presents demographics for the sample, those attending groups, and by experimental condition. Participants (n=738) were predominantly low-income, African-American (69%) girls (M age=16.5 years). Randomization resulted in two groups with no differences in race, ethnicity and poverty (measured by "free lunch" status). Among consenters, mean age of first vaginal sex (M=14.43 years) was younger than reported age for first oral (M=15.24 years) or anal (M=15.74 years) sex. Girls reported older steady partners (M=18.69), and averaged concurrent partners (M=1.43) at baseline.

Table I.

Demographic characteristics of participants (total consenters, total group attendees sample and by experimental condition)

|

Categorical Variables |

Consented Attendees n (%) |

GRP Attendees n (%) |

SRR intervention Attendees n (%) |

Control Attendees n (%) |

χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | ||||||

| Black/African-American | 510 (69%) | 463 (73%) | 243 (74%) | 220 (71%) | ||

| White/Caucasian | 67 (9%) | 48 (8%) | 19 (6%) | 29(9%) | ||

| Mixed/multiracial | 79 (11%) | 71 (11%) | 43 (13%) | 28(9%) | ||

| Other | 82 (11%) | 57 (9%) | 24 (7%) | 33 (11%) | 7.26 | .064 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic | 125 (17%) | 101 (16%) | 57(17%) | 44 (14%) | ||

| Not Hispanic | 613 (83%) | 538 (84%) | 272 (83%). | 266 (86%) | 1.18 | .278 |

| Free Lunch | ||||||

| Free Lunch | 513 (69%) | 446 (70%) | 234 (72%) | 212 (69%) | ||

| No Free Lunch | 225 (31%) | 189 (30%) | 92 (28%) | 97 (31%) | .76 | .382 |

|

Continuous Variable |

Consented Attendees |

Total Attendees |

SRR intervention Attendees |

Control Attendees |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M | SD | n | M | SD | n | M | SD | n | M | SD | F | p | |

| Age (years) | 738 | 16.50 | 1.3 | 639 | 16.42 | 1.24 | 329 | 16.41 | 1.24 | 310 | 16.43 | 1.24 | .05 | .823 |

Procedures

Regulatory approvals

IRB approval from participating institutions was obtained. The IRBs waived parental consent because recruitment occurred in healthcare settings where adolescents could be seen without parental consent. A Federal Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained and the trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT 00161343).

Recruitment

Girls were recruited from youth development centers, adolescent health services, and school-based centers in upstate New York. Prospective participants were screened by age and interest, then verbally consented to more thorough private screenings at the intervention site, providing informed consent and tracking information. Consent was verified by an independent participant advocate.

Randomization

Block randomization was used to assign participants to intervention condition. Condition assignment was known only to the project director until each group was filled and facilitators assigned.

Baseline assessment

Participants completed an audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI). ACASIs have demonstrated validity of socially-sensitive behavior reporting, and allow persons with lower literacy to participate [23]. Participants reported demographics and health behaviors including sexual behavior using items adapted from previous research [24–26]. These included age at first vaginal, oral, and anal sex; age of steady sexual partner; number of current male sexual partners; and episodes of protected and unprotected vaginal and anal sex (past 3-months) with steady and non-steady partners. Responses were summed to determine episodes of protected and unprotected sex (vaginal, anal) with all partners, and number of current male partners [27]. Participants provided urine specimens that were tested for Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (GC) (Becton Dickinson BD ProbeTecET Amplified DNA assay kit) then told the time and date of group meetings, and received $10 for data collection.

Interventions

Both interventions consisted of four, weekly, 120-minute sessions and two 90-minute booster (“reunion”) sessions at 3 and 6 months post-intervention. Groups comprised 6–9 girls who received $15 for each session attended.

Fifteen women diverse in age, race, ethnicity, discipline, and experience were trained to facilitate the manualized intervention. From this pool, we selected new randomized pairings of facilitators for each of the more than 100 cohorts receiving the intervention.

The SRR intervention was guided by the Information – Motivation – Behavioral Skills (IMB) Model [28]. The intervention (a) provided HIV information, (b) increased readiness to reduce risk behaviors (motivation), and (c) instructed, modeled, and allowed girls to practice interpersonal and self-management skills facilitating SRR and condom use. The intervention addressed concerns of girls, such as how to persuade a partner to use a condom, obtaining condoms and how fertility could be jeopardized by risky sexual behavior. The communication skills components have shown success in reducing sexual risk behaviors in adolescent girls [29].

The structure and content of the intervention included developmentally appropriate strategies such as games, interactive group activities, and skits. Initial sessions involved practicing basic skills. As sessions progressed, scenarios became more challenging and drew upon participants’ experiences. Booster sessions at 3 and 6 months post-intervention provided additional reinforcement of intervention components.

The health promotion condition had the same number of sessions and was led by the same facilitators to reduce the chance that intervention effects could be attributed to factors such as total contact time, group interaction or support, or facilitator attention. This control group consisted of general health promotion topics (nutrition, breast health, anger management). As with the SRR group, the IMB constructs were used as determinants of general health behaviors; these groups provided information, motivational strategies to change specific behaviors, and assertive communication and negotiation skills exercises.

Sessions were audiotaped and rated with respect to manual adherence and motivational approach. A review of every session for the first month of study was conducted; then a random selection of 25% from both groups were reviewed to determine intervention fidelity. Independent raters scored group facilitators at 97% fidelity to content and process.

Follow-up assessments

Three, six, and twelve months post-intervention, participants returned to complete an ACASI; at 6 and 12 months, participants provided a urine sample for CT and GC testing receiving $20 for each follow-up. At the end of the study, data from girls’ medical charts were abstracted from participating medical health clinics by RAs blinded to condition to identify additional infections, and positive pregnancy tests outside of those documented by our testing protocol. Participants received treatment for all positive results through a health care provider unrelated to the research study so that counseling and contact referrals could remain private.

Data Analyses

We followed intent-to-treat principle and included all girls randomized to groups in the analyses. Analyses controlled for age, ethnicity, race, and poverty as well as baseline status of the dependent measure.

To test the study hypotheses, we used regression analyses. Zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP) regression analyses were used for count data (frequency of sexual behavior) with substantial numbers of zeroes. For ZIP models, two regression equations were estimated simultaneously: (a) a logistic regression model to predict whether specific types of sexual behavior occurred (e.g., reported protected vaginal sex), and (b) a Poisson regression model to predict the values of episodes of that sexual activity. ZIP models allowed for the possibility that different variables may predict whether a girl had participated in a sexual behavior as well as frequency.

We analyzed impact of the intervention on number of sex partners. We classified number of partners into three categories: 0 partners, 1 partner, and 2 or more partners. These categorical data were then modeled using generalized logit regression, assessing differences between those girls with: (a) 0 partners and 1 partner, and (b) 0 partners and 2 or more partners. Prior to assessing the primary hypotheses, cases with missing data were evaluated to assess potential biases on the outcomes. The ZIP model was evaluated with 3, 6, and 12 month post-intervention data for each outcome, controlling for the baseline value of the variable and six covariates: age, white race, multi-racial, other ethnicity, Hispanic, free lunch, and treatment condition. We modeled each follow-up visit separately.

RESULTS

Figure 1 illustrates participant flow. Of 1778 girls who were screened, 765 (43%) did not meet eligibility criteria (71% reporting no sex within 3 months, 23% were pregnant or recently gave birth). Among eligible participants, 738 consented (most who declined cited lack of time due to work or school) and 639 attended the SRR (n=329, 51%) or the control group (n=310, 49%). Group assignment was not associated with attrition at 12-months (b=.000, p=.17). The only baseline characteristic associated with attrition was age, that is, older girls were more likely than younger girls (b=.160, p=.05) to be lost to follow-up.

Figure 1.

Consort table on Participant Recruitment and Retention

Intervention Efficacy

Table II presents the results for each outcome by condition.

Table II.

Baseline and follow-up sexual frequency measures (by condition) ; zero-inflated Poisson regression analyses of intervention effects

| Sexual Risk Reduction Intervention | Control | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Episodes | # of Episodes | Any Episodes | # of Episodes | # of Episodes | Number of times | |||||

| n | Yes (%) | Mean | SD | n | Yes (%) | Mean | SD | b1 (SE) | b2 (SE) | |

| Vaginal sex (total) | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 3243 | 292 (90.1) | 15.94 | 19.49 | 309 | 283 (91.6) | 14.68 | 16.87 | .114 (.280) | .081 (.021)*** |

| 3 Months | 278 | 229 (82.4) | 10.94 | 12.65 | 259 | 221 (85.3) | 13.13 | 14.39 | .225 (.241) | −.150 (.026)*** |

| 6 Months | 284 | 219 (77.1) | 10.76 | 13.56 | 262 | 229 (87.4) | 13.56 | 15.64 | .786 (.241)** | −.137 (.025)*** |

| 12 Months | 249 | 206 (82.7) | 14.54 | 17.70 | 235 | 198 (84.3) | 16.02 | 18.45 | .123 (.253) | −.140 (.024)*** |

| Unprotected vaginal sex | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 324 | 216 (66.7) | 6.68 | 9.95 | 309 | 211 (68.3) | 6.37 | 9.31 | .043 (.173) | .067 (.032)* |

| 3 Months | 278 | 162 (58.3) | 4.47 | 7.03 | 259 | 162 (62.5) | 5.17 | 7.49 | .205 (.187) | −.085 (.041)* |

| 6 Months | 284 | 154 (54.2) | 5.13 | 8.26 | 262 | 176 (67.2) | 6.10 | 8.83 | .622 (.187)*** | .035 (.037) |

| 12 Months | 249 | 170 (68.3) | 7.03 | 11.13 | 235 | 171 (72.8) | 8.09 | 11.04 | .292 (.208) | −.100 (.034)** |

| Unprotected vaginal sex With steady partner |

||||||||||

| Baseline | 324 | 206 (63.6) | 6.55 | 10.56 | 309 | 190 (61.5) | 6.16 | 9.99 | −.125 (.167) | .019 (.032) |

| 3 Months | 277 | 148 (53.4) | 4.52 | 8.07 | 257 | 152 (59.1) | 5.32 | 8.67 | .247 (.184) | −.087 (.041)* |

| 6 Months | 284 | 147 (51.8) | 5.45 | 9.81 | 258 | 166 (64.3) | 6.61 | 11.05 | .585 (.186)** | .007 (.036) |

| 12 Months | 243 | 154 (63.4) | 6.71 | 10.73 | 231 | 160 (69.3) | 7.60 | 10.64 | .330 (.202) | −.067 (.036)a |

| Unprotected vaginal sex With non-steady partner(s) |

||||||||||

| Baseline | 321 | 41 (12.8) | .36 | 1.31 | 308 | 47 (15.3) | .44 | 1.37 | .202 (.241) | −.148 (.151) |

| 3 Months | 278 | 33 (11.9) | .35 | 1.21 | 257 | 32 (12.5) | .29 | 1.09 | .203 (.306) | .236 (.185) |

| 6 Months | 283 | 21 (7.4) | .20 | .94 | 262 | 36 (13.7) | .35 | 1.20 | .963 (.333)** | .413 (.237)a |

| 12 Months | 244 | 29 (11.9) | .30 | 1.01 | 235 | 36 (15.3) | .48 | 1.54 | .163 (.288) | −.373 (.194)a |

Unstandardized coefficient from logistic regression component of ZIP model.

Unstandardized coefficient from Poisson regression component of ZIP model.

n represents number of consenters who actually participated

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

SE = standard error.

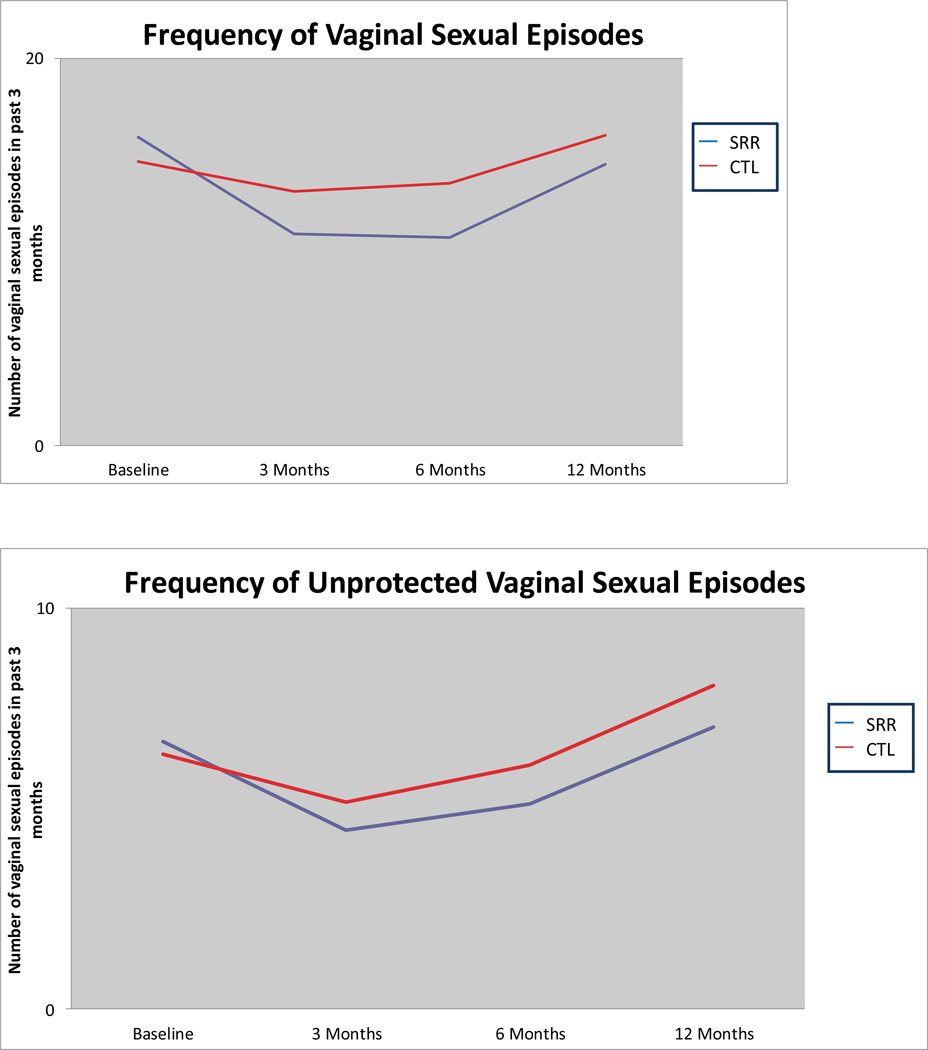

Total Vaginal Sex Episodes (protected and unprotected)

As depicted in Figure 2 and Table II, girls in the SRR group had fewer episodes of vaginal sex at each follow-up time point (all ps < 0.0001). The SRR intervention reduced the mean frequency of all episodes of vaginal sex (protected and unprotected) for the SRR participants compared to the control group. Compared to controls, the reduction in frequency of vaginal sex from baseline was 14% at 3-months, 12% at 6-months, and 23%, at 12-months.

Figure 2.

Frequency of vaginal sex

Unprotected Vaginal Sex

Similar findings emerged for any unprotected vaginal sex (Figure 2 and Table II). Although SRR participants reported having more unprotected sex episodes than the control participants at baseline, the Poisson model indicated they had fewer episodes at 3 (p<0.05) , 6 and 12 months (p< 0.005) follow-up. The SRR intervention reduced the mean frequency of unprotected vaginal sex for participants, compared to control participants, by an amount of 8% at 3-months and 9% at 12-months. Although episodes were fewer in the SRR intervention group at 6-months, the outcome was not statistically significant.

Unprotected Vaginal Sex with Steady Partners

The SRR group had a significant reduction in amount of unprotected sex with steady partners at 3-months (p<.05); with reductions also observed at 12-months (although not statistically significant) (p=0.06). The intervention reduced the frequency of unprotected vaginal sex with steady partners for the SRR intervention, as compared to controls, by 8% at 3-months and 6% at 12-months.

Unprotected Vaginal Sex with Non-Steady Partners

No difference emerged from the Poisson model. At 12-months SRR girls reported less unprotected sex with non-steady partners than did controls (p=.05), however, the low baseline rate of sex with non-steady partners reduced the power of the analysis.

Abstinence

The effect of the SRR intervention was significant for the logistic model (to predict whether any sexual activity occurred) at 6-months (p=0.0011); thus, a higher proportion of girls were abstinent in the SRR group than in the control group, with an odds ratio of 2.19 (log OR=0.7859, CI: [1.37, 3.52]). For girls reporting sex with a steady partner at baseline, more SRR girls reported not having sex with a steady partner at the 6-month follow-up than did girls in the control group (OR=1.79, CI: [1.25, 2.58]). Although the intervention effect did not reach statistical significance, more girls in the intervention group reported abstinence than those in the control group at 3 and 12 months.

Number of Sexual Partners

Table III presents number of partners by condition and unstandardized coefficients from the generalized logit model at 3, 6 and 12 month follow-up. In this model, having no sexual partners was selected as the referent level; we modeled the probability of having one partner versus this referent level as well as the probability of having two or more partners versus this referent level. Consequently, there were two coefficients for each follow-up outcome. Data indicated that SRR participants had fewer sex partners than those in the control condition; this effect was significant at the 6-month follow-up. At 6 months, the chance of participants having a sexual partner was reduced by one-half (OR=0.536), and the odds of having two or more partners was reduced by one-third (OR=0.368).

Table III.

Baseline and follow-up number of sexual partners (by condition; generalized logit analyses of intervention effects

|

Sexual Risk Reduction intervention |

Control | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | b (SE) | OR | 95% CI OR | ||

| Baseline | ||||||

| Total | 325 | 309 | ||||

| 0 partners | 25 (7.7) | 14 (4.5) | ||||

| 1 partner | 207 (63.7) | 197 (63.8) | 0 vs. 1 | −.465 (.352) | .628 | .315 – 1.251 |

| 2 or more partners | 93 (28.6) | 98 (31.7) | 0 vs. 2 or more | −.604 (.367) | .547 | .266 – 1.123 |

| 3 Months | ||||||

| Total | 278 | 259 | ||||

| 0 partners | 39 (14.0) | 26 (10.0) | ||||

| 1 partner | 186 (66.9) | 178 (68.7) | 0 vs. 1 | −.313 (.278) | .731 | .424 – 1.261 |

| 2 or more partners | 53 (19.1) | 55 (21.2) | 0 vs. 2 or more | −.279 (.332) | .757 | .395 – 1.451 |

| 6 Months | ||||||

| Total | 284 | 262 | ||||

| 0 partners | 46 (16.2) | 23 (8.8) | ||||

| 1 partner | 195 (68.7) | 183 (69.8) | 0 vs. 1 | −.623 (.278)* | .536 | .311 – .926 |

| 2 or more partners | 43 (15.1) | 56 (21.4) | 0 vs. 2 or more | −1.001 (.333)** | .368 | .191 – .706 |

| 12 Months | ||||||

| Total | 249 | 236 | ||||

| 0 partners | 31 (12.4) | 23 (9.7) | ||||

| 1 partner | 173 (69.5) | 164 (69.5) | 0 vs. 1 | −.242 (.303) | .785 | .434 – 1.421 |

| 2 or more partners | 45 (18.1) | 49 (20.8) | 0 vs. 2 or more | −.336 (.352) | .715 | .359 – 1.424 |

Note: SE = standard error; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Biological evidence of intervention efficacy was also assessed. Medical records of 323 participants (51%) were reviewed and rates of pregnancy and STI (gonorrhea or chlamydia) over the 12-month follow-up period were obtained. Logistic regression revealed that intervention condition was not associated with obtaining the medical record data (B=.057, p=.729, OR=1.059). However, girls reporting their race as “other” (B=1.161, p=.003, OR=3.192) were overrepresented in the medical record review while Hispanic girls (B=-.639, p=.042, OR=.528) were underrepresented. Neither baseline sexual activity (i.e., rates of sexual activity, rates of unprotected sexual) nor the interaction terms of sexual activity with intervention condition approached significance when predicting the presence or absence of medical record data.

The medical chart data revealed a cumulative difference in pregnancies over the 12-month follow-up period. Seventeen participants (6.3%) in the SRR group and 32 participants (12.9%) in the control group had a documented positive pregnancy test (B=−.823, p=.009, OR=.439). We also assessed differences in STI rates obtained by urine sample testing at baseline, 6 and 12 months post-intervention. There were no differences between groups in STI rates by direct testing of urine or chart audit. Post-intervention, 46 (15.6%) girls in the SRR intervention tested positive by urine analysis for STIs (either GC or CT) and 45 (16.4%) in the control group. Experimental condition was not related to these rates (B=−.067, p=.772, OR − .935). By chart audit, 19 additional STI cases were identified post baseline, 10 girls participating in the SRR intervention, and 9 girls in the control group. Again, experimental condition remained unrelated to the presence of STI post-intervention (B=−.063, p=.768, OR=.939).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that a female-tailored, theoretically-guided intervention helped girls reduce their sexual risk behavior over one year. Girls receiving the intervention were more likely to be sexually abstinent post-intervention, report less unprotected vaginal sex and fewer sexual acts; for those with a medical chart, fewer new pregnancies were documented. The latter is especially impressive given that the intervention did not specifically address pregnancy prevention or contraception. However, contrary to expectation, we did not observe any reduction in STI rates over the 12-month interval, but this may reflect (at least in part) low baserates of STIs in this sample. Overall, a conceptually guided approach to sexual risk-reduction showed promise in reducing sexual risk behavior and unintended pregnancy. Incorporating contraceptive content into the intervention could be expected to augment these effects.

Maintenance of initial risk reduction over time remains an important challenge for prevention science [30]. In this study, the largest reductions were observed at the 3-month follow-up, with subsequent assessments suggesting a return toward baseline levels for girls who remaining sexually active. Booster sessions at 3 and 6-months appeared to support maintenance of intervention gains at 3-months with slight increases of gains at 6-months (cf. Figure 2). Decay of intervention effect occurred over time but the frequency of sexual-risk behaviors still remained less than that of the control condition. At 12-months, which showed the largest increase in number of vaginal sexual episodes, there had been no booster sessions for 6-months suggesting a possible connection between maintaining intervention gains and timing of booster sessions. Increasing risk behavior is expected as teens mature into young adulthood [31–33] so it is possible that intervention benefits were cancelled by developmental increases. However, our data do not allow us to test this hypothesis. These results point out the need for improved maintenance strategies in the context of HIV, STI, and pregnancy prevention programs and investigating how long boosters can be expected to bolster an intervention’s effect over time.

This study is unique in that we recruited a predominantly African-American, sample of adolescent girls residing in a mid-size urban city. During the trial, we screened over 1700 girls and enrolled three-quarters of eligible adolescents. Even though the intervention required that adolescents arrange their own transportation to attend multiple sessions in community venues, attendance was strong. This, coupled with participants’ satisfaction ratings, provides evidence of intervention acceptability. Anecdotal comments from participants also suggest that the social support inherent in the groups was valued. Our findings add to a growing literature documenting the value of female-focused prevention programs [10, 18, 34] as well as to the larger literature of prevention programs for adolescents in general [14, 18, 35].

Sexual partnerships for adolescents tend to be relatively brief and, for girls, serial monogamy is common [36, 37]. Although we did not collect data about identities of partners, we suspect that many partnerships changed over time. Tracking the sexual partnerships and networks of youth is an emerging research area that can strengthen our understanding of the epidemiology of STIs [38–40]. Given the limits of our data, we cannot differentiate whether the changes in abstinence that we observed occurred with the same or a new partner and if this behavior was an active decision to practice secondary abstinence or was related to change in relationship status or fewer opportunities for sexual behavior. It is possible that girls who received the risk-reduction intervention were better able to negotiate abstinence at the onset of a new relationship; however, this hypothesis requires additional investigation.

Strengths of this study include (a) use of a RCT design with a structurally equivalent control condition that addressed important adolescent health concerns; (b) strong retention of participants over one year; (c) use of an intent-to-treat data analytic approach to allow a rigorous analysis of intervention impact; and (d) use of medical chart data to assess pregnancy impact. In addition we increased the external validity of the intervention by recruitment from multiple venues. We also used a diverse group of facilitators to provide the motivational intervention, demonstrating the intervention’s translatability into settings where employees are often diverse in race, ethnicity, age, and educational preparation.

Study limitations included (a) sampling from a single city, limiting generalizability to other population subgroups with different demographic characteristics; (b) use of self-report data, which are vulnerable to cognitive and social biases; (c) incomplete data on pregnancy due to community-based recruitment; (d) loss of follow-up ofgirls as they age; (e) insufficient sample to see changes in STIs; and (f) follow-ups limited to 12-months. Sampling bias was also an issue as the sample was comprised only of individuals who, meeting the criteria, voluntarily agreed to participate.

Continued refinement of gender-specific prevention interventions for adolescent girls remains paramount. Research should assess what is the minimal dose needed to produce positive outcomes, and determine critical components of effective interventions. Clarifying what tailoring is needed for interventions to be feasible, appealing, and effective for specific subpopulations of adolescent girls is an important next step in prevention science.

Acknowledgements

Dianne Morrison-Beedy received funding as PI and Xin M. Tu and Michael P. Carey as Co-Investigators from the National Institute of Nursing Research (R01 NR008194).

I affirm that everyone who has contributed significantly to this manuscript has been acknowledged.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTION

This sexual risk-reduction intervention tested in a RCT with 738 adolescent girls increased abstinence and decreased unprotected vaginal sex, number of partners, and unintended pregnancies. Results demonstrate the value of risk-reduction interventions tailored to girls, who at greater risk for STIs than boys.

Contributor Information

Dianne Morrison-Beedy, Senior Associate Vice President, USF Health Dean, College of Nursing, University of South Florida.

Sheryl H. Jones, School of Nursing, University of Rochester

Yinglin Xia, Research Assistant Professor, Department of Biostatistics and Computational Biology, University of Rochester Medical Center.

Xin Tu, Professor and Associate Chair, Department of Biostatistics and Computational Biology, Director, Statistical Consulting Service: Director, Division of Psychiatric Statistics, University of Rochester

Hugh F. Crean, Assistant Professor of Clinical Nursing, Center for Research & Evidence-Based Practice School of Nursing, University of Rochester

Michael P. Carey, Professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Professor of Behavioral and Social Sciences, and Director, Centers for Behavioral and Preventive Medicine, The Miriam Hospital and Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University.

References

- 1.Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance - United States, 2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2010 Jun 4;59(SS5):1–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance - United States, 2009. MMWR Surveillance Summaries. 2010 Jun 4;59(5):1–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenberg MD, Gurvey JE, Adler N, et al. Concurrent sex partners and risk for sexually transmitted diseases among adolescents. Sex Transm Dis. 1999 Apr;26(4):208–212. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199904000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 2004. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS surveillance in adolescents and young adults, slide 8. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2006 Disease Profile. Atlanta, GA: National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [cited 2011];HIV among women. 2011 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/women/index.htm.

- 8.Siebold C. Factors influencing young women's sexual and reproductive health. Contemp Nurse. 2011 Feb;37(2):124–136. doi: 10.5172/conu.2011.37.2.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basen-Engquist K, Coyle KK, Parcel GS, et al. Schoolwide effects of a multicomponent HIV, STD, and pregnancy prevention program for high school students. Health Education and Behavior. 2001 Apr;28(2):166–185. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Harrington KF, et al. Efficacy of an HIV prevention intervention for African American adolescent girls: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004 Jul 14;292(2):171–179. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jemmott JB, 3rd, Jemmott LS, Fong GT, et al. Effectiveness of an HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention for adolescents when implemented by community-based organizations: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2010 Apr;100(4):720–726. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morrison-Beedy D, Carey MP, Kowalski J, et al. Group-based HIV risk reduction intervention for adolescent girls: evidence of feasibility and efficacy. Research in Nursing and Health. 2005 Feb;28(1):3–15. doi: 10.1002/nur.20056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bryan ADFJ, Fisher WA, Murray DM. Understanding condom use among heroin addicts in methadone maintenance using the information-motivation-behavioral skills model. Subst Use Misuse. 2000;2000(35):451–471. doi: 10.3109/10826080009147468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson BT, Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Huedo-Medina TB, Carey MP. Interventions to reduce sexual risk for human immunodeficiency virus in adolescents: A meta-analysis of trials, 1985–2008. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2011;165:77–84. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darrow WW, Montanea JE, Gladwin H. AIDS-Related Stigma Among Black and Hispanic Young Adults. AIDS Behav. 2009 Dec;13(6):1178–1188. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9601-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barker DH, Swenson RR, Brown LK, et al. Blocking the Benefit of Group-Based HIV-Prevention Efforts during Adolescence: The Problem of HIV-Related Stigma. AIDS Behav. 2012 Apr;16(3):571–577. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0101-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Application of the theory of gender and power to examine HIV-related exposures, risk factors, and effective interventions for women. Health Educ Behav. 2000 Oct;27(5):539–565. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Rose ES, et al. Efficacy of sexually transmitted disease/human immunodeficiency virus sexual risk-reduction intervention for african american adolescent females seeking sexual health services: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2009 Dec;163(12):1112–1121. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Huedo-Medina TB, Warren MR, et al. Efficacy of Behavioral Interventions to Increase Condom Use and Reduce Sexually Transmitted Infections: A Meta-Analysis, 1991 to 2010. Jaids. 2011 Dec;58(5):489–498. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31823554d7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrison-Beedy D, Carey MP, Crean HF, et al. Risk Behaviors Among Adolescent Girls in an HIV Prevention Trial. West J Nurs Res. 2011 Aug;33(5):690–711. doi: 10.1177/0193945910379220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenberg JHM, MacGowan R, Celentano D, Gonzales V, Van Devanter N, Lifshay J. Modeling intervention efficacy for high-risk women. The WINGS Project. Eval Health Prof. 2000;23(2):123–148. doi: 10.1177/016327870002300201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schinke SPST, Fang L. Longitudinal outcomes of an alcohol abuse prevention program for urban adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(5):451–457. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanable PA, Carey MP, Brown JL, et al. Test-retest reliability of self-reported HIV/STD-related measures among African-American adolescents in four U.S. cities. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009 Mar;44(3):214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carey MP, Braaten LS, Maisto SA, et al. Using information, motivational enhancement, and skills training to reduce the risk of HIV infection for low-income urban women: a second randomized clinical trial. Health Psychology. 2000 Jan;19(1):3–11. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carey MP, Carey KB, Maisto SA, et al. HIV risk behavior among psychiatric outpatients: association with psychiatric disorder, substance use disorder, and gender. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2004 Apr;192(4):289–296. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000120888.45094.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carey MP, Maisto SA, Kalichman SC, et al. Enhancing motivation to reduce the risk of HIV infection for economically disadvantaged urban women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997 Aug;65(4):531–541. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.4.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schroder KE, Carey MP, Vanable PA. Methodological challenges in research on sexual risk behavior: I. Item content, scaling, and data analytical options. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003 Oct;26(2):76–103. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2602_02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1992 May;111(3):455–474. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morrison-Beedy D. Communication Strategies to Facilitate Difficult Conversations about Sexual Risk in Adolescent Girls. Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management. 2012;19(2):69–74. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calsyn DA, Crits-Christoph P, Hatch-Maillette MA, et al. Reducing sex under the influence of drugs or alcohol for patients in substance abuse treatment. Addiction. 2010 Jan;105(1):100–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02812.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Costello EJ, Sung M, Worthman C, et al. Pubertal maturation and the development of alcohol use and abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007 Apr;88(Suppl 1):S50–S59. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sales JM, Brown JL, Diclemente RJ, et al. Age Differences in STDs, Sexual Behaviors, and Correlates of Risky Sex Among Sexually Experienced Adolescent African-American Females. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011 Sep 20; doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steinberg L. A dual systems model of adolescent risk-taking. Dev Psychobiol. 2010 Apr;52(3):216–224. doi: 10.1002/dev.20445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jaworski BC, Carey MP. Effects of a brief, theory-based STD-prevention program for female college students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001 Dec;29(6):417–425. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00271-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson BT, Carey MP, Marsh KL, et al. Interventions to reduce sexual risk for the human immunodeficiency virus in adolescents, 1985–2000: a research synthesis. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2003 Apr;157(4):381–388. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.4.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown RT, Cromer BA. The pediatrician and the sexually active adolescent. Sexual activity and contraception. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1997 Dec;44(6):1379–1390. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70565-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silverman JG, McCauley HL, Decker MR, et al. Coercive forms of sexual risk and associated violence perpetrated by male partners of female adolescents. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011 Mar;43(1):60–65. doi: 10.1363/4306011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Foulkes HB, Pettigrew MM, Livingston KA, et al. Comparison of sexual partnership characteristics and associations with inconsistent condom use among a sample of adolescents and adult women diagnosed with Chlamydia trachomatis. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009 Mar;18(3):393–399. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.0840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gorbach PM, Drumright LN, Holmes KK. Discord, discordance, and concurrency: comparing individual and partnership-level analyses of new partnerships of young adults at risk of sexually transmitted infections. Sex Transm Dis. 2005 Jan;32(1):7–12. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000148302.81575.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee JK, Jennings JM, Ellen JM. Discordant sexual partnering: a study of high-risk adolescents in San Francisco. Sex Transm Dis. 2003 Mar;30(3):234–240. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200303000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]