Abstract

Networks of brain regions having synchronized fluctuations of the blood oxygen level-dependent functional magnetic resonance imaging (BOLD fMRI) time-series at rest, or “resting state networks” (RSNs), are emerging as a basis for understanding intrinsic brain activity. RSNs are topographically consistent with activity-related networks subserving sensory, motor, and cognitive processes, and studying their spontaneous fluctuations following acute drug challenge may provide a way to understand better the neuroanatomical substrates of drug action. The present within-subject double-blind study used BOLD fMRI at 3T to investigate the functional networks influenced by the non-benzodiazepine hypnotic zolpidem (Ambien®). Zolpidem is a positive modulator of γ-aminobutyric acidA (GABAA) receptors, and engenders sedative effects that may be explained in part by how it modulates intrinsic brain activity. Healthy participants (n= 12) underwent fMRI scanning 45 min after acute oral administration of zolpidem (0, 5, 10, or 20 mg), and changes in BOLD signal were measured while participants gazed at a static fixation point (i.e., at rest). Data were analyzed using group independent component analysis (ICA) with dual regression and results indicated that compared to placebo, the highest dose of zolpidem increased functional connectivity within a number of sensory, motor, and limbic networks. These results are consistent with previous studies showing an increase in functional connectivity at rest following administration of the positive GABAA receptor modulators midazolam and alcohol, and suggest that investigating how zolpidem modulates intrinsic brain activity may have implications for understanding the etiology of its powerful sedative effects.

Keywords: BOLD fMRI, resting state, functional connectivity, zolpidem, hypnotic, GABAA

1. Introduction

The measurement of spontaneous task-independent fluctuations in the blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signal during functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is a means for improving our understanding of intrinsic brain function. Although low-frequency fluctuations of the BOLD time series at rest originally were believed to arise from physiological and technical noise, this activity has been shown to be organized within neural networks that may provide insight into the functional relatedness or connectivity among the brain regions within those specified networks (see reviews by Fox and Raichle, 2007 and Rogers et al., 2007). These so-called “resting state networks” (RSNs) are topographically consistent with activity-related networks subserving sensory, motor, and cognitive processes (Smith et al., 2009), and a number of them can be differentiated reliably on the basis of their hemodynamic-independent electrophysiological correlates (Britz et al., 2010; Mantini et al., 2007). Because RSNs are consistent across individuals (Damoiseaux et al., 2006), resting state fMRI is emerging as a potential clinical tool for characterizing neuropsychiatric disease states (reviewed in Auer, 2008 as well as in Greicius, 2008), brain injury (Cauda et al., 2009; Voss and Schiff, 2009), aging (Andrews-Hanna et al., 2007; Damoiseaux et al., 2008; Li et al., 2009; Stevens et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2007), and the acute pharmacological actions of drugs (Esposito et al., 2010; Greicius et al., 2008; Hong et al., 2009; Kelly et al., 2009; Khalili-Mahani et al., 2011; Kiviniemi et al. 2005; Li et al., 2000; Rack-Gomer et al., 2009).

Resting state fMRI may be a particularly useful tool for identifying the neurobiological substrates of drug action. One prominent reason for this is the relative ease with which this imaging paradigm can be implemented. Evaluating the brain at rest not only requires little from study participants, but assessments are not confounded by drug effects on activity or task performance (e.g., attention; see discussion in Licata et al., 2011a). Moreover, as the understanding grows regarding how RSNs represent functional neuronal systems (Smith et al., 2009), examining drug effects on functional connectivity may reveal important mechanistic information about drug action. A recent study showed that morphine and alcohol produced distinct effects on resting state functional connectivity in healthy volunteers (Khalili-Mahani et al., 2011). The observed effects on connectivity were consistent with previously demonstrated drug-induced changes in receptor binding and/or cerebral metabolism within regions that had been implicated in mediating the distinct physiological and subjective effects of morphine and alcohol (Khalili-Mahani et al., 2011). Similarly, a recent rodent study showed that acute challenge with d-amphetamine or fluoxetine caused functionally connected brain regions to respond in patterns consistent with known activity in the dopaminergic or serotonergic neurotransmitter systems, respectively (Schwarz et al., 2007). These findings suggest that such changes in resting state activity are likely related to drug-associated changes in synaptic activity, and they may provide a neurobiological proxy or marker that can be used to characterize psychoactive drug effects across individuals.

The present study employed BOLD fMRI to investigate the modulation of RSNs by zolpidem in healthy volunteers as a means for beginning to reveal the neurobiological correlates of sedative/hypnotic action. Zolpidem (Ambien®) is a positive allosteric modulator of γ-aminobutyric acidA (GABAA) receptors, and it is one of the most frequently prescribed sleep aids in the United States (Morlock et al., 2006). Zolpidem’s interaction with GABAA receptors underlies its clinical effectiveness as a hypnotic (Lloyd and Zivkovic, 1988), but this mechanism of action alone does not provide sufficient explanation for zolpidem’s superiority in the treatment of insomnia. Other drugs including the antidepressant trazodone (Stahl, 2009) and the melatonin agonist ramelteon (Pandi-Perumal et al., 2009) are used successfully for addressing sleep problems, but they work primarily through other pharmacological systems. Resting state fMRI following acute challenge with various doses of zolpidem presented a unique opportunity to explore the substrates of sedative/hypnotic action, particularly because little is known about how this drug acts within the brain. The limited existing literature regarding its neurometabolic effects (e.g., Finelli et al., 2000; Gillin et al., 1996; González-Pardo et al., 2006) in conjunction with the known distribution of zolpidem-sensitive GABAA receptors (Heldt and Ressler, 2007; Wisden et al., 1992; Zezula et al., 1988), together led us to hypothesize that drug action would be observed primarily in sensory, motor, and limbic networks.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Participants

Twelve healthy male (6) and female (6) volunteers between the ages of 21–35 (mean ± SD age was 24.2 ± 2.3 years) and with approximately 17 years of education (mean ± SD education was 16.6 ± 1.7 years) completed the study. Right-handed non-smoking volunteers who reported ≤10 lifetime recreational experiences with drugs of abuse other than alcohol, had no family history of alcoholism, were never diagnosed with a DSM-IV Axis I or neurological disorder, were not taking regular medications, had no scanning contraindications, and tolerated the high dose of zolpidem during a pilot laboratory visit (i.e., did not vomit or report nausea following acute oral administration of 20 mg zolpidem), were invited to participate in the study. Participants were instructed not to eat breakfast and they were required to abstain from alcohol and caffeine for at least 12 hr prior to all study visits. Upon arriving at the laboratory on each visit, participants were screened for drug use (QuickTox® urine screen kits, Branan Medical Corporation; Irvine, CA) and breath alcohol level (AlcoSensor, Intoximeter; Saint Louis, MO). Female participants underwent a QuPID® urine pregnancy test (Stanbio Laboratory; Boerne, TX); pregnancy was a contraindication in this study. Any participant who tested positive on any screen would have been rescheduled and sent home (although none were). A standard breakfast was provided to all participants to control for stomach contents on the rate of drug absorption. Round-trip taxicab transportation was provided for all participants on each study day. This study was reviewed and approved by the McLean Hospital Institutional Review Board, and it was in accord with the Declaration of Helsinki. All volunteers provided informed consent and were compensated for their participation.

2.2 Study design

There were four separate fMRI scanning visits in this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, within-subject study (for a total of 48 scanning sessions). Participants were administered one of four treatments (0, 5, 10, or 20 mg zolpidem) approximately 45 min (46.28 ± 6.18 min, mean ± SD) prior to the beginning of the BOLD resting state scan. All scanning sessions began at 10:30 am. The resting state scan preceded a passive visual stimulation scan as well as a key press task scan, both of which were reported on previously (Licata et al., 2011a).

Prior to beginning all BOLD scans participants were engaged in conversation to ensure they were awake; they were instructed to remain awake and not to engage in active thought, but instead, to relax and focus their gaze upon a static black asterisk presented on a uniform gray background. This fixation point was displayed at the center of the screen throughout the scan. An eyes-open resting state paradigm was chosen in lieu of an eyes-closed paradigm due to the potential soporific effects of zolpidem. This paradigm aimed to increase the likelihood that participants uniformly would not have succumbed to the potential hypnotic effects of drug treatment although there was risk of reducing the overall amplitude of spontaneous BOLD fluctuations (e.g., McAvoy et al., 2008). Employing the fixation may be construed as involving an attentional component in our “resting state”, however, a recent study demonstrated that resting functional connectivity was equivalent between paradigms requiring participants to keep their eyes open regardless if they viewed a fixation or gazed toward a blank screen (Van Dijk et al., 2010). Importantly, our study aimed to assess the differences in RSN function attributed to drug treatment, thereby obviating the subtle differences between the specific paradigms that could be used. The fixation point was presented using a rear-projection system running Presentation® software (Version 11.0; Neurobehavioral Systems, Inc.; Albany, CA).

2.3 Magnetic resonance imaging

Scans were performed on a 3 Tesla Siemens Trio MR imaging system (Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany). A 3-plane scout scan (conventional FLASH sequence with isotropic voxels of 2.8 mm) was acquired and used for prescription of the fMRI image stack. All functional MRI data were acquired using gradient echo EPI, TR/TE= 3000/30 ms, 224 × 224 mm FOV, 41 3.5-mm interleaved axial slices starting from the spinal cord covering the whole brain, no gap, AP readout, 64 × 64 pixel, full k-space acquisition, no SENSE acceleration; pulse sequence-enhanced version of the Siemens epibold, yielding isotropic 3.5 mm voxels. The spontaneous resting state BOLD scan (200 TRs) lasted approximately 10 min. Automatic second order shimming was performed over the fMRI imaging volume prior to acquisition. A conventional T1 scan was performed on the same functional prescription; therefore it had identical susceptibility distortion ("matched-warped"; identical geometry to the fMRI scans except for 256 × 256 pixels). A standard T1 weighted MP-RAGE3D scan (FOV= 256 × 256 × 170 mm, 256 × 256 × 128) also was collected for registration of the data to standard space.

2.4 Heart Rate Monitoring

Heart rate data were collected using MRI-compatible equipment (In Vivo Research; Orlando, FL). This measure was collected every second throughout the scan, and computed as 1-min averages over the 10-min resting state scan. Heart rate was analyzed using two-way repeated measures ANOVAs examining the within-subjects factors of treatment by time.

2.5 Data Pre-Processing

Except where noted, data processing was performed with FSL release 4.1 (FMRIB Analysis Group; Oxford University, United Kingdom). Pre-processing procedures included nonlinear de-spiking filtering (using an in-house program), motion correction with MCFLIRT (Jenkinson et al., 2002), brain extraction using BET (Smith, 2002), spatial smoothing with a Gaussian kernel of full-width half-maximum 6 mm and high-pass temporal filtering with Gaussian-weighted least-squares straight-line fitting with σ= 100 s. Functional MRI data were aligned with the matched-warped scan with six degrees of freedom, which then was aligned to the high-resolution MPRAGE scan with 12 degrees of freedom. In the final registration step, the MPRAGE scan was aligned with the MNI152 standard brain with 12 degrees of freedom. Rendering of the functional results in MNI space was performed once, following concatenation of the three alignments into a single matrix. A summary of this registration was monitored for each run of each participant (no registration errors were found). Finally, the data were re-sampled to (2 mm3) resolution.

2.6 Statistical Modeling

2.6.1 Independent component analysis (ICA)

Pre-processed data were analyzed using MELODIC (c.f., Beckmann and Smith, 2004), which implemented a temporal concatenation ICA. This method decomposes the data from all 48 scans into a set of spatial maps displaying the spatial pattern associated with that component as it is distributed over the brain, as well as a set of corresponding temporal waveforms that describes the time progression of each component. Both are composites over all scans and participants. Together, these spatio-temporal patterns are the underlying “hidden” signals that comprise the BOLD fMRI time series, and they correspond to underlying RSNs and artifactual processes that give rise to the BOLD signals. The ICA is superior to seed-based correlation for probing large-scale RSNs for our purposes because it is much more robust to cardiovascular confounds and motion artifacts (Cole et al., 2010), and it permits investigation of all RSNs simultaneously.

Automatic dimensionality estimation yielded 58 independent components that were estimated by the ICA. For visualization purposes to facilitate identification of brain networks, these independent component (IC) maps are maps of z-values assessing a voxel’s membership in the IC “network” (common to the set of participants). They were thresholded from z= 3–10, which is approximately what the threshold was using a mixture modeling approach for statistical assessment of the IC maps (Beckmann et al., 2004). At this threshold, a number of known networks were split into sub-components as compared to component spatial patterns that were consistent with the literature for the most frequently reported major RSNs (Beckmann et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2009) and intrinsic connectivity networks identified from task-activation studies (Laird et al., 2011). Thus, the number of components was reduced to 40, which yielded several of the major RSNs in a spatial configuration consistent with the literature. However, to ensure stable convergence of the ICA, the ICA was run eight times and followed by a meta-level ICA fed by all of the spatial maps from the eight decompositions following the procedures used in Smith et al. (2009), all at a dimensionality of 40. The networks of interest were only those RSNs involved in sensory, motor, and limbic function. Given that there were only 40 maps, these RSNs were easily identified by visual inspection as those consistent with brain networks reported previously (Laird et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2009). While similar to other resting state studies during which participants’ thoughts were unconstrained during a task-free experimental paradigm, the presence of a pharmacologic drug challenge could alter the spatial configuration of observable networks. However, given the overlap of RSNs with the intrinsic connectivity networks (ICNs) associated with task performance (identified by Smith et al. (2009) and Laird et al. (2011)), we refer to the networks identified as RSNs for sake of simplicity.

2.6.2 Dual Regression

The multi-session temporal concatenation ICA employed here yielded one spatial map and one time course for each group IC, as a composite for all participants and scans. To identify alterations in RSN connectivity between conditions, the individual subject-specific spatial maps and time courses corresponding to each group independent component, which reflect the variability associated with the different drug conditions, were estimated using the dual regression procedure (Beckmann et al., 2009; Filippini et al., 2009). In the first stage of the dual regression, all 40 unthresholded IC spatial maps were used as spatial regressors in a whole-brain multivariate multiple regression against each participant’s fMRI dataset. This yielded 40 scan-specific time courses, one for each group IC. By including all of the independent components in the multiple regression, any voxel with contributions from multiple signal sources (for example, from coupling with a RSN and from motion effects) will have these effects “partialled out” into their separate contributions by the multiple regression. In addition, because all 40 ICs were used in the multiple regression, “noise” components corresponding to, for example, white matter and cerebral spinal fluid also were represented in the subject-specific general linear models (GLMs). Therefore they were accounted for at the individual participant level dual regression. This process is similar to traditional seed-based connectivity analyses that also include confound regressors in the model to account for these noise signals, the difference being that ICA is a model-free approach to deriving the confound regressors. The subject-specific time courses were normalized to unit variance and then used in a second multiple regression against the individual participant’s dataset in order to identify voxels correlated with each RSN time course, thus identifying the spatial map corresponding to each RSN that was unique to the participant. These maps of partial regression coefficients reflect both the strength of an individual voxel’s time course relative to the independent time course (e.g., amplitude), as well as the correlation between the individual voxel’s time course and the IC time course, or the degree of integration of that voxel into the network. Conversion of the t-statistic maps output from the second stage of the dual regression to partial correlations using r = t/{sqrt(t^2 + residual DF)}, DF = degrees of freedom of the multiple regression, will result in spatial maps that reflect a more pure measure of correlation that provides a second metric of within-network functional connectivity and is informative of the spatial topography of the RSN. Preliminary findings from previous work suggest correlation coefficients are more sensitive to alterations in synchrony of BOLD timecourses than the partial regression coefficients that are the standard output of the dual regression implemented in FSL (Nickerson et al., 2010). Prior to estimation and inference, correlation maps were Fisher z-transformed using: ztransr = 0.5*{ln[(1+r)/(1−r)]}*DF.

2.7 Estimation and Inference

To assess within-network functional connectivity differences between the different drug conditions, subject-specific spatial maps from stage two of the dual regression were probed in a voxel-wise manner using a linear model contrast in a multiple regression GLM framework. We assessed group functional connectivity differences by comparing both RSN within-network correlation and amplitude using the partial correlation and regression coefficient spatial maps from stage two of the dual regression. For both metrics, the subject-specific spatial maps corresponding to each of the networks of interest were collected across participants into two separate 4-dimensional files (one per original component map, with the fourth dimension being participant/condition for a total of 48 3-D volumes concatenated into each file for a given component). To model the effects of placebo and three doses of zolpidem, we implemented a one-factor four-levels repeated measures ANOVA using the design matrix as recommended on the FSL website (http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/FEAT/UserGuide). RSNs were assessed for group differences in within-network functional connectivity using threshold-free cluster enhancement (TFCE; Smith and Nichols, 2009; height parameter= 2, extent parameter= 0.5) in combination with permutation testing (FSL Randomise; Nichols and Holmes, 2002; Smith et al., 2004), which is necessary given the unknown distribution of the TFCE statistic. FSL Randomise was used for permutation testing. The repeated measures ANOVA model was implemented in Randomise by specifying an exchangeability block to indicate the subject blocks over which to permute data in order to preserve the covariance structure (http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/Randomise). The F-tests revealed significant effects in many of our networks of interest. Consequently, post hoc contrasts were performed to assess the differences between the 20 mg dose of zolpidem relative to placebo. This contrast was examined specifically because the 20 mg dose engendered measurable behavioral effects unequivocally in these participants relative to the other two doses (Licata et al., 2011b). For this paired contrast, we applied a novel permutation-based correction to correct for the number of tests across both voxels and components. Permutations among doses within the same participant were performed to maintain exchangeability, for a total of 5000 permutations. Control of family-wise error (FWE) across the number of voxels and components tested was achieved using outputs of FSL Randomise in the following manner: 1) for each component, the same seed was set in the call to Randomise to ensure that the permutations would be identical for all 5000 permutations for every component, 2) the output text files for all thirteen components, each containing a 5000-element long vector of the maximum TFCE statistic over all voxels obtained for each permutation (used to control the family-wise error over all voxel), were loaded into Matlab (The Mathworks, Natick, MA), 3) a maximum of the maximums data matrix (a vector containing 5000 values) was created by recording for each permutation, the max(TFCE) across components, and 4) the resulting data matrix was the probability density function for the maximum TFCE across voxels and components. This information then was used to control the FWE across voxels and components at p< 0.05 by identifying the threshold corresponding to the 95th percentile.

Between-network functional connectivity differences also were assessed using the FSLNets toolbox (http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/FSLNets). Briefly, the partial correlation coefficients (Pearson's r) between the individual participant time courses for each of the RSNs of interest that were generated by the first stage of the dual regression procedure were calculated. These correlation coefficients were then Fisher z-transformed and paired t-tests were conducted to compare between-network connectivity. Permutation testing was used to infer between-network differences in functional connectivity (20 mg vs. placebo), accounting for FWE by correcting for multiple tests with the significance set at p< 0.05.

3. Results

3.1 ICA

RSNs of interest in the current study were those that comprised sensory, motor, and limbic networks that have been reported previously (Laird et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2009). We identified a number of these networks, and they are shown in axial slices covering the whole brain in the Supplemental Material. Sensory networks included five occipital and occipito-temporal cortical RSNs comprised of brain regions likely involved in visual processes and two temporal RSNs that may be related to auditory processing (Supp. Fig. 1). Occipital networks included one comprised of peripheral areas V1 and V2, one containing central field representation of areas V1 and V2, a lateral occipito-temporal network, a network comprised of right temporal and fusiform regions, and a network comprised of occipito-temporal and medial temporal regions. Temporal networks included one comprised of the middle and superior temporal gyri, and another containing primary auditory cortex, Heschl’s gyrus, and parietal operculum. Networks likely to be related to motor function (Supp. Fig. 2) included one comprised of somatosensory cortex and supramarginal gyrus, somatosensory cortex with precentral and postcentral gyri, a network containing the precentral gyrus, and another containing the cerebellum. Eight other networks were obtained from the ICA. Four contained midbrain regions and four included primarily prefrontal areas (Supp. Fig. 3). These networks included RSNs comprised of the basal ganglia, a network containing hippocampus, amygdala, orbitofrontal cortex, and insula, an orbitofrontal/ventrolateral prefrontal cortex and insula-containing network, another comprised of anterior cingulate, posterior cingulate/precuneus, and posterior occipito-parietal regions, a medial prefrontal cortex network, both left and right fronto-parietal networks, and a ventromedial prefrontal cortex.

3.2 Group Differences in RSN Functional Connectivity

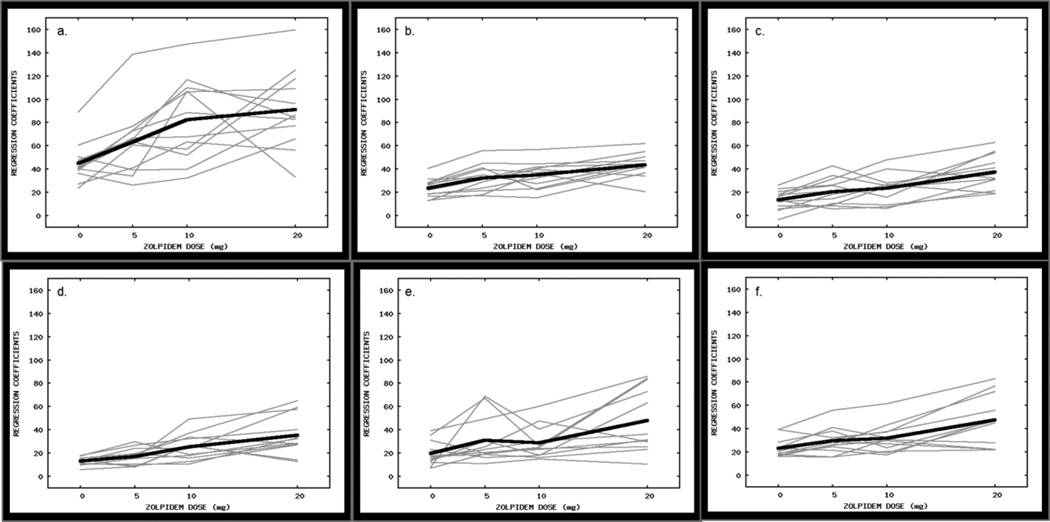

In Figs. 1–4, a single orthogonal view of each RSN (shown in green, overlaid on the MNI-152 2 mm standard brain) is shown in each column. Voxels with significant differences in functional connectivity between 20 mg zolpidem and placebo are shown in red-yellow (FWE p< 0.05, corrected). Fig. 1 shows group differences in functional connectivity in what appears to be visual RSNs. There were statistically significant group differences in the within-network functional connectivity in each of these networks. Similarly, Figs. 2–4 depict the group differences seen in auditory-, motor-, and limbic-related networks, respectively. Our focus on the 20 mg zolpidem versus placebo contrast was based on the reliable subjective drug effects engendered by that dose (Licata et al. 2011b), and obviated the issue surrounding multiple comparisons. However, plots of the regression coefficients averaged over voxels for which functional connectivity was statistically greater at 20 mg than placebo are shown for all four doses in Figs. 5 and 6 to illustrate potential dose-dependent trends in the response. Statistical analysis confirmed that the trends observed in these components were linear in nature vs. non-linear. All components exhibited statistically significant linear trends (p< 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Group differences (red-yellow) within occipital and occipito-temporal cortical RSNs (green) including: a) peripheral areas V1 and V2, b) central field representation of areas V1 and V2, c) lateral occipito-temporal regions, d) right temporal/fusiform regions, and e) occipito-temporal and medial temporal regions. Each network shows increased within-network functional connectivity following zolpidem (20 mg) relative to placebo (FWE corrected for multiple comparisons across voxels and components, p< 0.05).

Fig. 4.

Group differences (red-yellow) in functional connectivity within midbrain and prefrontal RSNs (green) including: a) basal ganglia, b) hippocampus, amygdala, orbitofrontal cortex, and insula, c) orbitofrontal and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, and insula. Networks (a) and (c) exhibit increased within-network functional connectivity following zolpidem (20 mg) relative to placebo (FWE corrected for multiple comparisons across voxels and components, p< 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Group differences (red-yellow) in functional connectivity within two temporal RSNs (green) including: a) middle and superior temporal gyri, and b) primary auditory cortex, Heschl’s gyrus, and parietal operculum. Network shown in (a) exhibits increased within-network functional connectivity following zolpidem (20 mg) relative to placebo (FWE corrected for multiple comparisons across voxels and components, p< 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Plots show the PEs averaged over significant voxels, across dose, within each RSN exhibiting group differences (thin gray lines). Panels (a–e) correspond to those networks depicted in Fig. 1, while panel (f) corresponds to the network depicted in Fig. 2a. The values were averaged across all participants (thick black lines).

Fig. 6.

Plots show the PEs averaged over significant voxels, across dose, within each RSN exhibiting group differences (thin gray lines). Panels (a–c) correspond to those networks depicted in Fig. 3, while panels (d, e) correspond to those networks depicted in Fig. 4a, c. The values were averaged across all participants (thick black lines).

The maps shown in Figs. 1–4 are those for the comparisons of amplitude; the comparisons of z-transformed correlations exhibited effects in overlapping regions that were not as robust against the correction for multiple voxels and components (e.g., of smaller spatial extent in most networks). However, given that the differences in amplitude and correlation overlapped for nearly all of these networks, we are unable to ascribe our group differences to either amplitude or correlation changes alone. Thus, for simplicity, we will hereafter refer to the group differences as alterations in functional connectivity (where amplitude and correlation are different aspects of connectivity). As seen in the figures, there were alterations in almost every network, suggesting that the highest dose of zolpidem has a widespread effect on local functional connectivity. There were no statistically significant group differences (p< 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons) in the between-network functional connectivity of any of the RSNs as assessed by the correlation of each network's time course with other network time courses. In order to ensure that these effects on connectivity were not a reflection only of the global noise unaccounted for by the dual regression procedure, post-hoc exploratory (corrected only for multiple tests across voxels, not components) analyses of the connectivity for all the components were undertaken to determine if differential effects existed depending on the networks examined. Indeed, patterns of functional connectivity differences that were not increases in within-network connectivity as observed in our primary networks of interest were observed in other networks (for which we had no a priori hypotheses). For instance, in a network containing the medial prefrontal cortex (shown in Supp. Fig. 3e), no drug-induced within- or between-network changes in connectivity were observed. Similarly, the left frontoparietal network (shown in Supp. Fig. 3g) also was unchanged, while the right frontoparietal network (shown in Supp. Fig. 3f) exhibited a focal increase in connectivity between the network and the insula without any within-network changes. That the effects observed in these executive control- and attention-related networks (Seeley et al., 2007; Vincent et al., 2008) were different from those in the sensory networks supports the conclusion that the widespread effects on local within-network functional connectivity without large-scale between-network changes are zolpidem-specific effects rather than just physiological noise.

3.3 Heart Rate Measurements

Full sets of heart rate data (i.e., data for all four treatment conditions) from the scanning session were collected for only eight participants due to equipment failures. Heart rate varied slightly by zolpidem dose such that the average (mean ± SEM) number of beats per minute for placebo was 67.15 ± 2.05 while it was 73.17 ± 2.13 at the highest dose of 20 mg. However, there was no significant treatment effect. There was an effect of time [F(3,316)= 2.18, p= 0.04] such that heart rate during the seventh minute (72.96 ± 0.96) of the scan was higher than that during the second minute (67.51 ± 0.96) of the scan (p= 0.008). However, because this one finding did not survive correction for multiple comparisons (p< 0.05/45= 0.001), the effect of heart rate during the scan may have been spurious. Moreover, the relatively small number of complete heart rate datasets precluded considering change in heart rate in our models due to inadequate power.

4. Discussion

The present results demonstrate that acute oral administration of the GABAergic drug zolpidem increased functional connectivity within a number of sensory, motor, and limbic RSNs. More specifically, the highest dose of zolpidem (20 mg) increased the correlation and/or amplitude of BOLD signal fluctuations within networks comprised of primary motor cortex, pre- and post-central gyri, the supplemental motor area, and basal ganglia, a somatomotor network, and somatosensory areas. Connectivity also was enhanced in medial and lateral visual cortical regions, auditory networks, and language areas including the superior temporal gyrus. In association with the limbic system, zolpidem increased connectivity in networks containing the basal ganglia, hippocampus, amygdala, orbitofrontal cortex, and prefrontal cortical areas. The overall increase in resting state connectivity appears intuitive given the increases in “rest” observed following challenge with other sedating drugs such as midazolam and alcohol (Esposito et al., 2010; Greicius et al., 2008; Khalili-Mahani et al., 2011; Kiviniemi et al., 2005). Specifically, the benzodiazepine midazolam enhanced BOLD signal synchrony within visual, auditory, and motor cortices during conscious sedation (Greicius et al., 2008; Kiviniemi et al., 2005), while alcohol also enhanced connectivity primarily in sensory and motor areas with large effects observed within auditory, somatosensory, sensorimotor, cerebellar, and visual RSNs (Esposito et al., 2010; Khalili-Mahani et al., 2011). These results also are consistent with reports of decreased RSN activity after stimulant administration to healthy volunteers (Li et al., 2000; Rack-Gomer et al., 2009).

A growing body of work has characterized specific and replicable spatiotemporal patterns of brain activity that fluctuate spontaneously at low frequencies (0.01–0.1 Hz) in the absence of goal-directed or task-related activity (e.g., Damoiseaux et al., 2006; De Luca et al., 2006; Mantini et al., 2007). Although RSN activity is organized in patterns that are topographically similar to those of functional networks (Smith et al., 2009), it has not been shown definitively that these patterns of activity necessarily represent anatomical connectivity (De Luca et al., 2006). However, the strong correlation between BOLD fluctuations and hemodynamic-independent electroencephalographic (EEG) rhythms (Britz et al., 2010; Mantini et al., 2007) suggests that BOLD signal changes at rest are related to neuronal activity rather than just reflecting low-frequency physiological or vascular noise entirely (De Luca et al., 2006). Despite the slower temporal resolution of BOLD relative to that of EEG and the likelihood that the RSN-EEG relationship is generated by more than one frequency band (Britz et al., 2010; Mantini et al., 2007), neuronal oscillatory activity provides a context for framing the modulation of RSNs as presented here.

Generally, benzodiazepines and related drugs such as zolpidem have a characteristic effect on EEG frequency bands such that they decrease cortical alpha (~8–12 Hz) power while increasing power in the beta (~13–30 Hz) and gamma (> 30 Hz) frequency bands (de Haas et al., 2010; Feige et al., 1999; Hall et al., 2010; Jensen et al., 2005; Link et al., 1991; van Lier et al., 2004). The GABAergic origin of the beta and gamma rhythms (Bartos et al., 2007; Mandema et al., 1992; Muthukumaraswamy et al., 2009) coupled to their contribution to sensorimotor processing, conscious perception, and cognitive function (Engel and Singer, 2001; Fell and Axmacher, 2011; Paik and Glaser, 2010; Ribary, 2005; Sauvé, 1999), together are relevant to the known ability of benzodiazepine-type drugs to engender a range of sensory, motor, and cognitive effects including sedation, anxiolysis, muscle relaxation, and anterograde amnesia. Accordingly, a recent magnetoencephalography (MEG) study showed that benzodiazepines modulate beta and gamma frequency bands in a manner coincident with the spatial distribution of GABAA receptors (Hall et al., 2010).

The gamma band may be of particular relevance to RSN modulation by a GABAergic drug such as zolpidem because oscillations in this frequency range have been shown to increase with increasing concentrations of GABA (Muthukumaraswamy et al., 2009). Given that GABAergic neurons tend to synchronize in the gamma frequency bandwidth (Faulkner et al., 1998; Traub et al., 1996; Whittington et al., 1995), the enhanced connectivity here may reflect synchrony among large populations of neurons across the brain that is driven by a zolpidem-induced increase in gamma (Fingelkurts et al., 2004). Because we found significant correlation chnages within a variety of networks, but not between networks in the present study, it is more likely that these pharmacological alterations are driving widespread local synchrony rather than globally distributed synchrony. In the absence of empirical electrophysiological measurements we can only speculate about the relationship between zolpidem’s effect on frequency oscillations and the extensive drug-induced increased correlations of the BOLD signals observed here, but these results are consistent with previous EEG studies demonstrating benzodiazepine-induced enhancements of connectivity (Alonso et al., 2010; Fingelkurts et al., 2004; Sampaio et al., 2007).

Regardless of the electrophysiological underpinnings, the zolpidem-induced increased correlation of within-network BOLD signal fluctuations implies synchronization, albeit of an ambiguous nature, that is likely to have significance with respect to drug effects on communication within the brain. Synchrony can be thought of as an efficient and precise means for controlling information processing by enhancing salience and local communication within connected networks, and thus serving a facilitating role (see review by Fries, 2005). However, alterations in synchrony have been implicated as mechanisms contributing to movement disorders (Brown, 2007; Schnitzler and Gross, 2005) and the cognitive dysfunction in neurodevelopmental disorders (Uhlhaas et al., 2008; 2010), as synchrony also may give rise to pathological rigidity that impedes the transfer of information. Thus, enhanced functional connectivity within networks may not reflect a more highly organized state per se, particularly because the facilitation of information transfer requires not just coherence, but that neuronal oscillations are matched in both frequency and phase (Fries, 2005), neither of which can be discerned from the changes in BOLD connectivity here. Instead the connectivity may reflect some aberrant state that occurs at the expense of task-related function. Our data support this notion since here we show that visual RSNs exhibited increased connectivity, while previously we reported that in these same participants zolpidem reduced BOLD activation during visual stimulation (Licata et al., 2011a). Similarly, acute challenge with alcohol increased resting state correlations in a visual RSN (Esposito et al., 2010) while prior to that it had been shown to reduce BOLD signal activation in visual cortical areas during presentation of a stimulus (Levin et al., 1998; Calhoun et al., 2004). Given that intoxication generally results in sensory and behavioral impairments, and this dose of zolpidem increased self-reported ratings of intoxicating-like effects in these participants (see Licata et al., 2011b), the idea that drug-induced increases in functional connectivity reflect a disruption to the brain is plausible (Esposito et al., 2010), and may further suggest that the increase in connectivity is a reflection of hindered neuronal communication.

The increases in RSN activity seen here are consistent not only with the electrophysiological response to massive inhibition engendered by a high dose of zolpidem, but also with previous drug effects on brain metabolism. Global reductions in metabolism as well as regionally specific reductions within the thalamus and occipital cortex have been observed following benzodiazepine administration (Volkow et al., 1995; Wang et al., 1996). Similarly, zolpidem specifically reduced cerebral glucose metabolism (Gillin et al., 1996) and cerebral blood flow (CBF; Finelli et al., 2000) in a number of frontal regions including white matter and anterior cingulate, as well as basal ganglia, insula, and hippocampus. In rodents, zolpidem also decreased oxidative metabolism within various limbic structures including prelimbic cortex, anterior cingulate, thalamus, hippocampus, mammillary nuclei, and the amygdala (González-Pardo et al., 2006), and together these observations are consistent with the distribution of zolpidem-specific GABAA receptors (Heldt and Ressler, 2007; Wisden et al., 1992; Zezula et al., 1988). However, zolpidem also increased CBF in parietal and occipital cortices, parahippocampal gyrus, and cerebellum (Finelli et al., 2000), collectively cautioning against assuming a simple relationship between inhibition and receptor distribution (see discussion of Khalili-Mahani et al., 2011), and further underscoring the need for a multi-modal imaging paradigm. Specifically, a study design including arterial spin labeling would permit the quantitative measurement of the impact drug administration has on cerebral blood flow, thereby controlling at least one physiological variable contributing to the BOLD signal and providing a useful biomarker of drug action (Chen et al., 2011; O’Gorman et al., 2008).

5. Limitations

5.1 Study Design

As mentioned above, the uni-modal nature of the present exploratory study is a limitation in so far as the absence of an empirical measurement of zolpidem’s effects on vasomotor tone limits interpretation of the data (Iannetti and Wise, 2007). Vascular fluctuations are important to consider because drug-induced changes in baseline resting perfusion influence the sensitivity of the BOLD signal (Brown et al., 2003; Cohen et al., 2002; Kemna and Posse, 2001). However, a recent study evaluating caffeine’s effects on resting functional connectivity demonstrated that when drug-induced alterations in CBF were taken into account, the reductions in connectivity were unchanged (Rack-Gomer et al., 2009).

Although both cardiac (Shmueli et al., 2007) and respiratory (Birn et al., 2008) fluctuations contribute to changes in the BOLD signal at rest, only heart rate data were collected during the scanning session, thus limiting the ability to determine the extent of physiological artifacts. However, statistical analyses in the present report revealed negligible effects of zolpidem on heart rate and previous laboratory studies failed to detect zolpidem-induced changes in respiration relative to placebo (Evans et al., 1990; McCann et al., 1993), suggesting that this omission was not of vital importance.

Another potentially limiting factor in our design was the use of an eyes-open resting state paradigm. Previous work has shown that keeping one’s eyes open in the resting state can reduce spontaneous activity (see Logothetis et al., 2009; McAvoy et al., 2008). While this may reduce baseline activity, the effect should be comparable across all doses, and our findings suggest that differences are readily detectable using an eyes-open paradigm.

5.2 Analysis

A particular limitation associated with our choice of using ICA to investigate alterations in functional connectivity is the inherent difficulty of making an a priori choice about dimensionality, which is necessary for “tuning” the ICA. Tuning the dimensionality depends upon identification of networks having the configuration that we expect based on those reported previously in the literature. Here we were interested in large-scale brain networks similar to those reported in Beckmann et al. (2005), Laird et al. (2011), and Smith et al. (2009). While our focus was on sensory, motor, and limbic networks, our observed spatial configurations were similar to networks observed in those previous studies, which were similar to one another as well. However, there were a few networks here that have not been reported previously, further underscoring the importance of showing all of the networks obtained in this kind of analysis.

Another factor to consider here with respect to assessing the similarity between the observed spatial configuration of components and those reported previously, is that this is a subjective step in the analysis procedure. Moreover, the ability to assess the generalizability of results may be influenced by the pharmacological challenge because the drug itself may cause alterations in the configuration of a network output from the group ICA, making it appear different from those previously reported networks. While we have shown all of the identifiable networks we obtained to mitigate this limitation, it is important to bear in mind that because participants were scanned while under the influence of a psychoactive drug, the observable resting state may not be identical to that observed in the absence of any pharmacological manipulation.

Finally, this exploratory report was restricted to the findings in networks of primary interest with respect to the well-known general sedative-like effects of zolpidem. It should be noted that work is in progress to undertake a more focused investigation of specific intoxication-related subjective effects of zolpidem and their relationship to alterations in functional connectivity within limbic networks. Overall, there are alterations in the shape of these networks (e.g., the specific spatial configuration), which were not observed in the sensory and motor networks reported in this work. Therefore, the effects observed in the sensory and motor networks are likely specific effects associated with the general sedation-like state.

6. Conclusions

We have shown that much like challenge with benzodiazepines (Greicius et al., 2008; Kiviniemi et al., 2005), zolpidem induces increased correlation in the BOLD signal time series within a number of RSNs rather than reducing functional coupling of brain regions or causing otherwise functional connections to deactivate (Fingelkurts et al., 2004; Sampaio et al., 2007). Zolpidem’s previously demonstrated effects on electrophysiology (e.g., van Lier et al., 2004) plus the zolpidem-induced alterations in within-network functional connectivity described here suggest that if zolpidem’s actions serve to synchronize oscillatory activity (Fingelkurts et al., 2004), it may be in a way that hinders neuronal communication thereby contributing to zolpidem’s generally sedative-like behavioral effects. While future pharmacological fMRI-EEG studies should determine this empirically, the present results demonstrate that not only is resting state fMRI complementary to task-dependent imaging, but it is an informative approach for understanding drug effects at the circuit or network level.

Supplementary Material

Fig. 3.

Group differences (red-yellow) in functional connectivity within RSNs consistent with motor cortical regions (green) including: a) somatosensory cortex and supramarginal gyrus, b) somatosensory cortex, precentral and postcentral gyri, and c) precentral gyrus. Each network exhibits increased within-network functional connectivity following zolpidem (20 mg) relative to placebo (FWE corrected for multiple comparisons across voxels and components, p< 0.05).

Highlights.

Synchronized BOLD fluctuations contain information about functional connectivity.

We challenged spontaneous brain activity using the GABAergic hypnotic zolpidem.

Zolpidem increased functional connectivity in sensory, motor, and limbic networks.

Effects were consistent with other GABA-related increases in BOLD signal synchrony.

Functional connectivity may reveal network substrates of sedative drug effects.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Tom Nichols for helpful discussions regarding the approach used to correct for multiple comparisons across voxels and components. This study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse grants K01 DA023659 (SCL) and R21 DA032257 (LDN). The funding source had no role in the study design, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, in the writing of this report, or in the decision to submit the report for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alonso JF, Mananas MA, Romero S, Hoyer D, Riba J, Barbanoj MJ. Drug effect on EEG connectivity assessed by linear and nonlinear couplings. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2010;31:487–497. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand A, Li Y, Wang Y, Wu J, Gao S, Bukhari L, Mathews VP, Kalnin A, Lowe MJ. Antidepressant effect on connectivity of the mood-regulating circuit: an FMRI study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1334–1444. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews-Hanna JR, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Lustig C, Head D, Raichle ME, Buckner RL. Disruption of large-scale brain systems in advanced aging. Neuron. 2007;56:924–935. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auer DP. Spontaneous low-frequency blood oxygenation level-dependent fluctuations and functional connectivity analysis of the ‘resting’ brain. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2008;26:1055–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartos M, Vida I, Jonas P. Synaptic mechanisms of synchronized gamma oscillations in inhibitory interneuron networks. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:45–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann CF, Smith SM. Probabilistic independent component analysis for functional magnetic resonance imaging. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2004;23:137–152. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2003.822821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann CF, DeLuca M, Devlin JT, Smith SM. Investigations into resting-state connectivity using independent component analysis. Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. B. 2005;360:1001–1013. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann CF, Mackay CE, Filippini N, Smith SM. Group comparison of resting-state fMRI data using multi-subject ICA and dual regression. NeuroImage. 2009;47(Suppl 1):S148. [Google Scholar]

- Birn RM, Murphy K, Bandettini PA. The effect of respiration variations on independent component analysis results of resting state functional connectivity. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2008;29:740–750. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britz J, Van De Ville D, Michel CM. BOLD correlates of EEG topography reveal rapid resting-state network dynamics. NeuroImage. 2010;52:1162–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P. Abnormal oscillatory synchronization in the motor system leads to impaired movement. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2007;17:656–664. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun VD, Altschul D, McGinty V, Shih R, Scott D, Sears E, Pearlson GD. Alcohol intoxication effects on visual perception: an fMRI study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2004;21:15–26. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauda F, Micon BM, Sacco K, Duca S, D’Agata F, Geminiani G, Canavero S. Disrupted intrinsic functional connectivity in the vegetative state. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2009;80:429–431. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.142349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Wan HI, O’Reardon JP, Wang DJ, Wang Z, Korczykowski M, Detre JA. Quantification of cerebral blood flow as biomarker of drug effect: arterial spin labeling phMRI after a single dose of oral citalopram. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011;89:251–258. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen ER, Ugurbil K, Kim SG. Effect of basal conditions on the magnitude and dynamics of the blood oxygenation level-dependent fMRI response. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:1042–1053. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200209000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DM, Smith SM, Beckmann CF. Advances and pitfalls in the analysis and interpretation of resting-state FMRI data. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2010;4 doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2010.00008. Article 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damoiseaux JS, Rombouts SA, Barkhof F, Scheltens P, Stam CJ, Smith SM, Beckmann CF. Consistent resting-state networks across healthy subjects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:13848–13853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601417103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damoiseaux JS, Beckmann CF, Arigita EJ, Barkhof F, Scheltens P, Stam CJ, Smith SM, Rombouts SA. Reduced resting-state brain activity in the “default network” in normal aging. Cereb. Cortex. 2008;18:1856–1864. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Haas SL, Schoemaker RC, van Gerven JM, Hoever P, Cohen AF, Dingemanse J. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationship of zolpidem in healthy subjects. J. Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:1619–1629. doi: 10.1177/0269881109106898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca M, Beckmann CF, De Stefano N, Matthews PM, Smith S. fMRI resting state networks define distinct modes of long-distance interactions in the human brain. NeuroImage. 2006;29:1359–1367. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel AK, Singer W. Temporal binding and the neural correlates of sensory awareness. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2001;5:16–25. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01568-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito F, Pignataro G, Di Renzo G, Spinali A, Paccone A, Tedeschi G, Annunziato L. Alcohol increases spontaneous BOLD signal fluctuations in the visual network. NeuroImage. 2010;53:534–543. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SM, Funderburk FR, Griffiths RR. Zolpidem and triazolam in humans: behavioral and subjective effects and abuse liability. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1990;255:1246–1255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner HJ, Traub RD, Whittington MA. Disruption of synchronous gamma oscillations in the rat hippocampal slice: a common mechanism of anaesthetic drug action. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;125:483–492. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feige B, Voderholzer U, Riemann D, Hohagen F, Berger M. Independent sleep EEG slow-wave and spindle band dynamics associated with 4 weeks of continuous application of short-half-life hypnotics in healthy subjects. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1999;110:1965–1974. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(99)00147-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fell J, Axmacher N. The role of phase synchronization in memory processes. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011;12:105–118. doi: 10.1038/nrn2979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippini N, MacIntosh BJ, Hough MG, Goodwin GM, Frisoni GB, Smith SM, Matthews PM, Beckmann CF, Mackay CE. Distinct patterns of brain activity in young carriers of the APOE-epsilon 4 allele. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:7209–7214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811879106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finelli LA, Landolt HP, Buck A, Roth C, Berthold T, Borbély AA, Achermann P. Functional neuroanatomy of human sleep states after zolpidem and placebo: a H215O- PET study. J. Sleep Res. 2000;9:161–173. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2000.00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingelkurts AA, Fingelkurts AA, Kivisaari R, Pekkonen E, Ilmoniemi RJ, Kähkönen S. Enhancement of GABA-related signaling is associated with increase of functional connectivity in human cortex. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2004;22:27–39. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MD, Raichle ME. Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:700–711. doi: 10.1038/nrn2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries P. A mechanism for cognitive dynamics: neuronal communication through neuronal coherence. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2005;9:474–480. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillin JC, Buchsbaum MS, Valladares-Neto DC, Hong CC-H, Hazlett E, Langer SZ, Wu J. Effects of zolpidem on local cerebral glucose metabolism during non-REM sleep in normal volunteers: A positron emission tomography study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;15:302–313. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Pardo H, Conejo NM, Arias JL. Oxidative metabolism of limbic structures after acute administration of diazepam, alprazolam and zolpidem. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2006;30:1020–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius M. Resting-state functional connectivity in neuropsychiatric disorders. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2008;21:424–430. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328306f2c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Kiviniemi V, Tervonen O, Vainionpää V, Alahuhta S, Reiss AL, Menon V. Persistent default-mode network connectivity during light sedation. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2008;29:839–847. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SD, Barnes GR, Furlong PL, Seri S, Hillebrand A. Neuronal network pharmacodynamics of GABAergic modulation in the human cortex determined using pharmaco-magnetoencephalography. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2010;31:581–594. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldt SA, Ressler KJ. Forebrain and midbrain distribution of major benzodiazepine-sensitive GABAA receptor subunits in the adult C57 mouse as assessed with in situ hybridization. Neuroscience. 2007;150:370–385. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong LE, Gu H, Yang Y, Ross TJ, Salmeron BJ, Buchholz B, Thaker GK, Stein EA. Association of nicotine addiction and nicotine’s actions with separate cingulate cortex functional circuits. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2009;66:431–441. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannetti GD, Wise RG. BOLD functional MRI in disease and pharmacological studies: room for improvement? Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2007;25:978–988. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasinski DR. Assessment of the abuse potential of morphine-like drugs (methods used in man) In: Martin WR, editor. Drug Addiction I. 45/1. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 1977. pp. 197–258. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. NeuroImage. 2002;17:825–841. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)91132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen O, Goel P, Kopell N, Pohja M, Hari R, Ermentrout B. On the human sensorimotor-cortex beta rhythm: sources and modeling. NeuroImage. 2005;26:347–355. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly C, de Zubicaray G, Di Martino A, Copland DA, Reiss PT, Klein DF, Castellanos FX, Milham MP, McMahon K. L-dopa modulates functional connectivity in striatal cognitive and motor networks: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:7364–7378. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0810-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemna LJ, Posse S. Effect of respiratory CO(2) changes on the temporal dynamics of the hemodynamic response in functional MR imaging. NeuroImage. 2001;14:642–649. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalili-Mahani N, Zoethout RM, Beckmann CF, Baerends E, de Kam ML, Soeter RP, Dahan A, van Buchem MA, van Gerven JM, Rombouts SA. Effects of morphine and alcohol on functional brain connectivity during “resting state”: A placebo-controlled crossover study in healthy young men. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2011;33:1003–1018. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiviniemi VJ, Haanpää H, Kantola JH, Jauhiainen J, Vainionpää V, Alahuhta S, Tervonen O. Midazolam sedation increases fluctuation and synchrony of the resting brain BOLD signal. Magn. Reson Imaging. 2005;23:531–537. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird AR, Fox PM, Eickhoff SB, Turner JA, Ray KL, McKay DR, Glahn DC, Beckmann CF, Smith SM, Fox PT. Behavioral interpretations of intrinsic connectivity networks. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2011;23:4022–4037. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin JM, Ross MH, Mendelson JH, Kaufman MJ, Lange N, Maas LC, Mello NK, Cohen BM, Renshaw PF. Reduction in BOLD fMRI response to primary visual stimulation following alcohol ingestion. Psychiatry Res. 1998;82:135–146. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(98)00022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SJ, Biswal B, Li Z, Risinger R, Rainey C, Cho JK, Salmeron BJ, Stein EA. Cocaine administration decreases functional connectivity in human primary visual and motor cortex as detected by functional MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 2000;43:45–51. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(200001)43:1<45::aid-mrm6>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Moore AB, Tyner C, Hu X. Asymmetric connectivity reduction and its relationship to “HAROLD” in aging brain. Brain Res. 2009;1295:149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licata SC, Lowen SB, Trksak GH, MacLean RR, Lukas SE. Zolpidem reduces the blood oxygen level-dependent signal during visual system stimulation. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2011a;35:1645–1652. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licata SC, Mashhoon Y, MacLean RR, Lukas SE. Modest abuse-related subjective effects of zolpidem in drug-naïve volunteers. Behav. Pharmacol. 2011b;22:160–166. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328343d78a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link CG, Leigh TJ, Fell GL. Effects of granisetron and lorazepam, alone and in combination, on the EEG of human volunteers. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1991;31:93–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1991.tb03863.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd KG, Zivkovic B. Specificity within the GABAA receptor supramolecular complex: a consideration of the new omega 1-receptor selective imidazopyridine hypnotic zolpidem. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1988;29:781–783. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90206-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logothetis NK, Murayama Y, Augath M, Steffen T, Werner J, Oeltermann A. How not to study spontaneous activity. NeuroImage. 2009;45:1080–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandema JW, Kuck MT, Danhof M. Differences in intrinsic efficacy of benzodiazepines are reflected in their concentration-EEG effect relationship. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1992;105:164–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantini D, Perrucci MG, Del Gratta C, Romani GL, Corbetta M. Electrophysiological signatures of resting state networks in the human brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:13170–13175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700668104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAvoy M, Larson-Prior L, Nolan TS, Vaishnavi SN, Raichle ME, d’Avossa G. Resting states affect spontaneous BOLD oscillations in sensory and paralimbic cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 2008;100:922–931. doi: 10.1152/jn.90426.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann CC, Quera-Salva MA, Boudet J, Frisk M, Barthouli P, Borderies P, Meyer P. Effect of zolpidem during sleep on ventilation and cardiovascular variables in normal subjects. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 1993;7:305–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1993.tb00244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morlock RJ, Tan M, Mitchell DY. Patient characteristics and patterns of drug use for sleep complaints in the United States: analysis of National Ambulatory Medical Survey Data, 1997–2002. Clin. Ther. 2006;28:1044–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthukumaraswamy SD, Edden RAE, Jones DK, Swettenhan JB, Singh KD. Resting GABA concentration predicts peak gamma frequency and fMRI amplitude in response to visual stimulation in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:8356–8361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900728106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols TE, Holmes AP. Nonparametric permutation tests for functional neuroimaging: a primer with examples. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2002;15:1–25. doi: 10.1002/hbm.1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson LD, Smith SM, Ongür D, Beckmann CF. Investigation of multi-subject ICA and dual regression for group comparisons of resting state networks. Proceedings of the 16th Annual Meeting of the Organization for Human Brain Mapping; Barcelona Spain. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- O’Gorman RL, Mehta MA, Asherson P, Zelaya FO, Brookes KJ, Toone BL, Alsop DC, Williams SC. Increased cerebral perfusion in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is normalized by stimulant treatment: a non-invasive MRI pilot study. NeuroImage. 2008;42:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.04.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paik SB, Glaser DA. Synaptic plasticity controls sensory responses through frequency-dependent gamma oscillation resonance. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2010;6:ii. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000927. e1000927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandi-Perumal SR, Srinivasan V, Spence DW, Moscovitch A, Hardeland R, Brown GM, Cardinali DP. Ramelteon: a review of its therapeutic potential in sleep disorders. Adv. Ther. 2009;26:613–626. doi: 10.1007/s12325-009-0041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rack-Gomer AL, Liau J, Liu TT. Caffeine reduces resting-state BOLD functional connectivity in the motor cortex. NeuroImage. 2009;46:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribary U. Dynamics of thalamo-cortical network oscillations and human perception. Prog. Brain Res. 2005;150:127–142. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)50010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers BP, Morgan VL, Newton AT, Gore JC. Assessing functional connectivity in the human brain by fMRI. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2007;25:1347–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio I, Puga F, Veiga H, Cagy M, Piedaded R, Ribeiro P. Influence of bromazepam on cortical interhemispheric coherence. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2007;65:77–81. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2007000100017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauvé K. Gamma-band synchronous oscillations: recent evidence regarding their functional significance. Conscious Cogn. 1999;8:213–224. doi: 10.1006/ccog.1999.0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzler A, Gross J. Normal and pathological oscillatory communication in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005;6:285–296. doi: 10.1038/nrn1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz AJ, Gozzi A, Reese T, Bifone A. In vivo mapping of functional connectivity in neurotransmitter systems using pharmacological MRI. NeuroImage. 2007;34:1627–1636. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmueli K, van Gelderen P, de Zwart JA, Horovitz SG, Fukunaga M, Jansma JM, Duyn JH. Low-frequency fluctuations in the cardiac rate as a source of variance in the resting-state fMRI BOLD signal. NeuroImage. 2007;38:306–320. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2002;17:143–155. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TEJ, Johansen-Berg H, Bannister PR, De Luca M, Drobnjak I, Flitney DE, Niazy RK, Saunders J, Vickers J, Zhang Y, De Stefano N, Brady JM, Matthews PM. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. NeuroImage. 2004;23(Suppl 1):S208–S219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Fox PT, Miller KL, Glahn DC, Fox PM, Mackay CE, Filippini N, Watkins KE, Toro R, Laird AR, Beckmann CF. Correspondence of the brain’s functional architecture during activation and rest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:1304–13045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905267106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Nichols TE. Threshold-free cluster enhancement: addressing problems of smoothing, threshold dependence and localization. NeuroImage. 2009;44:83–98. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl SM. Mechanism of action of trazodone: a multifunctional drug. CNS Spectr. 2009;14:536–546. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900024020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens MC, Pearlson GD, Calhoun VD. Changes in the interaction of resting-state neural networks from adolescence to adulthood. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2009;30:2356–2366. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub RD, Whittington MA, Stanford IM, Jeffreys JG. A mechanism for generation of long-range synchronous fast oscillations in the cortex. Nature. 1996;383:621–624. doi: 10.1038/383621a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlhaas PJ, Haenschel C, Nikolić D, Singer W. The role of oscillations and synchrony in cortical networks and their putative relevance for the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2008;34:927–943. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlhaas PJ, Roux F, Rodriquez E, Rotarska-Jagiela A, Singer W. Neural synchrony and the development of cortical networks. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2010;14:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk KRA, Hedden T, Venkataraman A, Evans KC, Lazar SW, Buckner RL. Intrinsic functional connectivity as a tool for human connectomics: theory, properties, and optimization. J. Neurophysiol. 2010;103:297–321. doi: 10.1152/jn.00783.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Lier H, Drinkenburg WH, van Eeten YJ, Coenen AM. Effects of diazepam and zolpidem on EEG beta frequencies are behavior-specific in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:163–174. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent JL, Kahn I, Snyder AZ, Raichle ME, Buckner RL. Evidence for a frontoparietal control system revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:3328–3342. doi: 10.1152/jn.90355.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Hitzemann R, Fowler JS, Pappas N, Lowrimore P, Pascani K, Overall J, Wolf AP. Depression of thalamic metabolism by lorazepam is associated with sleepiness. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1995;12:123–132. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(94)00068-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss HU, Schiff ND. MRI of neuronal network structure, function, and plasticity. Prog. Brain Res. 2009;175:483–496. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(09)17532-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GJ, Volkow ND, Overall J, Hitzemann RJ, Pappas N, Pascani K, Fowler JS. Reproducibility of regional brain metabolic responses to lorazepam. J. Nucl. Med. 1996;37:1609–1613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittington MA, Traub RD, Jeffreys JGR. Synchronized oscillations in interneuron networks driven by metabotropic glutamate receptor activation. Nature. 1995;373:612–615. doi: 10.1038/373612a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittington MA, Faulkner HJ, Doheny HC, Traub RD. Neuronal fast oscillations as a target site for psychoactive drugs. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000;86:171–190. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(00)00038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisden W, Laurie DJ, Monyer H, Seeburg PH. The distribution of 13 GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in the rat brain. I. Telencephalon, diencephalon, mesencephalon. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:1040–1062. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-03-01040.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T, Zang Y, Wang L, Long X, Li K, Chan P. Normal aging decreases regional homogeneity of the motor areas in the resting state. Neurosci. Lett. 2007;423:189–193. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zezula J, Cortés R, Probst A, Palacios JM. Benzodiazepine receptor sites in the human brain: autoradiographic mapping. Neuroscience. 1988;25:771–795. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90036-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.