Abstract

Purpose

Revision total knee arthroplasty (rTKA) is a complex procedure. Depending on the degree of ligament and bone damage, either primary or revision implants are used. The purpose of this study was to compare survival rates of primary implants with revision implants when used during rTKA.

Methods

A retrospective comparative study was conducted between 1998 and 2009 during which 69 rTKAs were performed on 65 patients. Most common indications for revision were infection (30 %), aseptic loosening (25 %) and wear/osteolysis (25 %). During rTKA, a primary implant was used in nine knees and a revision implant in 60.

Results

Survival of primary implants was 100 % at one year, 73 % [95 % confidence interval (CI) 41–100] at two years and 44 % (95 % CI 7–81) at five years. Survival of revision implants was 95 % (95 % CI 89–100) at one year, 92 % (95 % CI 84–99) at two years and 92 % (95 % CI 84–99) at five years. Primary implants had a significantly worse survival rate than revision implants when implanted during rTKA [P = 0.039 (hazard ratio = 4.56, 95 % CI 1.08–19.27)].

Conclusions

Based on these results, it has to be considered whether primary implants are even an option during rTKA.

Introduction

Over the past two decades, there has been an increase in the number of primary total knee arthroplasties (TKAs) performed [1, 2]. Despite good results of primary TKA, the number of revision TKAs (rTKAs) is rising [3], and a further increase in revision procedures in the future is predicted [4]. The demand for rTKA is expected to double by 2015, and a growth of 601 % is predicted for the United States between 2005 and 2030 [4]. A similar trend is expected for other Western countries.

Primary implants differ from revision implants in type of insert (constraint) and absence of stems and augmentations. During rTKA, the surgeon faces greater bone loss and more ligament damage, which may lead to instability of the knee joint [5, 6]. To overcome these problems, an implant with more constraint is recommended, and augmentations are commonly used to compensate for bone defects [7]. Although a posterior cruciate-retaining (PCR) or posterior stabilised (PS) prosthesis is generally implanted during primary TKA [8], most of the time, an rTKA requires a PS type [9]. Condylar-constrained knee (CCK) and rotating-hinge knee (RHK) types are also commonly used in rTKA [8–10]. When all ligaments are intact and of good quality and bone defects are limited, use of a PCR prosthesis will be sufficient. When only the posterior cruciate is damaged, a PS type is needed. A CCK is chosen when one or both collateral ligaments are inadequate. If medial and/or lateral collaterals and cruciate ligaments are compromised or when a severe deformity exists, an RHK is required [7, 8, 11, 12]. The consequence of using one of these types of revision prosthesis, however, is greater constraint. Higher constraint has negative effects on implant interfaces and is usually counteracted by press-fit stems [8, 13]. Hence, the choice of implant type is based on accurate assessment of ligament quality, bone loss and component fixation; the least degree of constraint necessary is recommended [8, 10, 14–16].

In handling bone defects, the classification of the Anderson Orthopaedic Research Institute is a useful guide [17]. In type 1 defects, primary prostheses may be used, whereas type 2 or 3 defects necessitate revision implants. Reasons to opt for a primary implant may also be greater surgeon experience and availability of revision components during the operation when encountering defects and the costs. However, theoretical advantages of using primary implants, such as ease of use, less time and cost savings, may be lost when inadequate reconstruction leads to early loosening.

Previous research has shown that compared with primary TKA, survival following rTKA is poorer [18–20]. The object of this study was to investigate whether there are differences in survival rates between primary and revision implants when implanted during rTKA.

Materials and methods

Study design and data collection

A retrospective comparative study was conducted. Data on 171 rTKAs performed between January 1998 and December 2009 at our institution were collected retrospectively. The cases were divided into two groups: knees that received a primary implant and knees that received a revision implant. Primary implants were defined as PCR and PS types without the use of stems or augmentations. Revision implants were defined as PS types with the use of stems or augmentations and CCK and RHK types. Survivorship and reason for any reoperation were documented. A telephone call to obtain this information was made to the patients, or to their general practitioner or surviving relative when a patient had died. The study was conducted in accordance with the regulations of the local medical ethical committee.

Study population

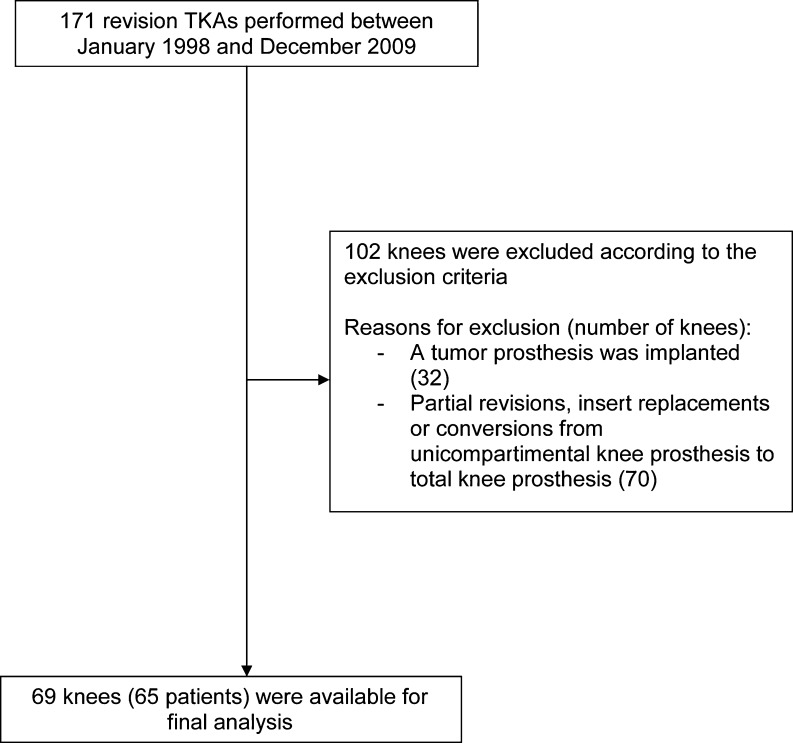

Patients with a primary total knee implant who underwent a total revision or reimplantation were included in the study. Excluded were partial revisions, insert replacements, conversions from a unicompartimental prosthesis to a total knee prosthesis and patients who received a tumour prosthesis during revision surgery. Eventually, 69 knees (65 patients) were available for final analysis (Fig. 1). The patient population consisted of 27 men and 38 women, with a mean age of 64.3 (range 30–85) years. Mean time between primary TKA and rTKA was 103.3 (range 2–276) months. The most common reasons for revision were infection (30 %), aseptic loosening of one or more components (25 %) and wear/osteolysis (25 %). During rTKA, nine knees received a primary implant and 60 knees received a revision implant. Of the nine knees receiving a primary implant, three received a NexGen Legacy posterior stabilised (NexGen PS; Zimmer, Warsaw, IN, USA), five an AGC PCR prosthesis (Biomet Inc., Warsaw, IN, USA) and one an LCS rotating platform (PS) prosthesis (Depuy Johnson & Johnson, Warsaw, IN, USA). Sixty revisions were performed with a NexGen revision implant with stems and augmentation. In 37 knees a PS insert was used, in 20 a semiconstrained insert (Legacy Condylar Constrained Knee, LCCK) and in three a rotating-hinge knee (RHK, NexGen).

Fig. 1.

Exclusion procedure

Surgical procedure

Revision TKA was performed by two senior orthopaedic surgeons (SKB and ALB) working at our institution. During rTKA, all components were removed and replaced by a primary or revision implant. The medial parapatellar approach was used in all procedures, and all femoral, tibial and patellar components were cemented. Stems were routinely uncemented but a press-fit was used. Infections were treated by two-stage revision. Postoperatively, all patients followed the same protocol, with early weight-bearing mobilisation permitted in cases with repair of contained defects. Otherwise, this was postponed to six to 12 weeks postoperatively, depending on individual situations.

Statistical analysis

Survival of primary implants used during rTKA was compared with survival of revision implants. The patient who was lost to follow-up was censored using the date of last contact at our hospital. Deceased patients were censored using the date of death. Kaplan–Meier survival analyses were performed to assess the survival of the two types of implant at one, two and five years. To study differences between groups and to adjust for potential confounders such as age, indication, sex and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, the Cox regression analysis was performed [21]. Additionally, variables of age, indication (septic or aseptic), sex and ASA classification were assessed for confounding. When the variable was a significant confounder, it was added to the Cox regression. The endpoint for survival following rTKA was defined as repeat revision when one or more component was removed or exchanged. Statistical analyses were performed using the PASW software package (version 18, SPSS, Chicago). A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

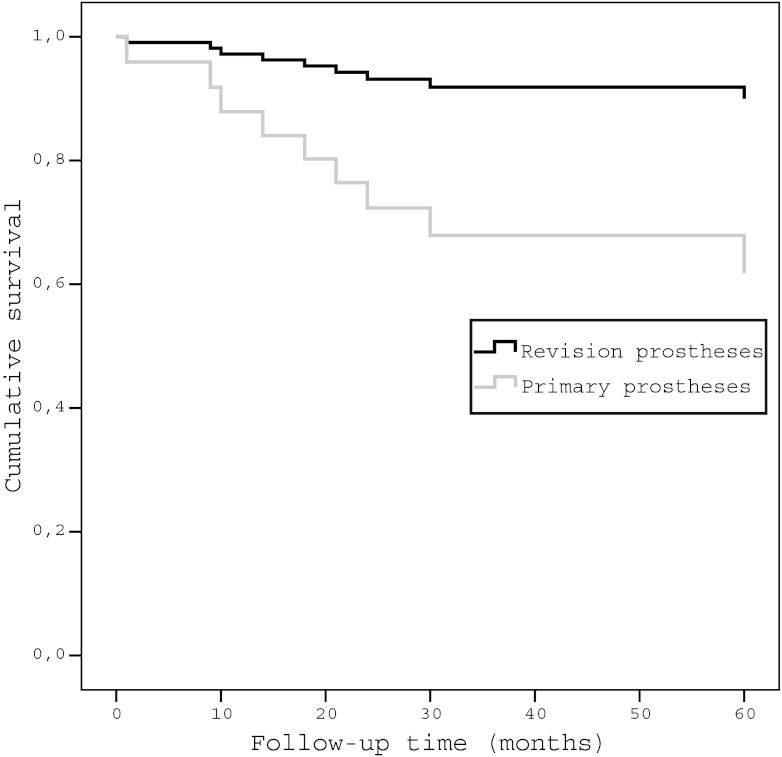

Mean survival of all rTKAs was 58.6 (range 1–161) months. Overall survival of both primary and revision implants was 96 % [95 % confidence interval (CI) 91–100] at one year, 89 % (95 % CI 82–97) at two years and 85 % (95 % CI 75–94) at five years. Survival of primary implants was 100 % at one year, 73 % (95 % CI 41–100) at two years and 44 % (95 % CI 7–81) at five years. Survival of revision implants was 95 % (95 % CI 89–100) at one year, 92 % (95 % CI 84–99) at two years and 92 % (95 % CI 84–99) at five years. The use of a revision implant during revision surgery had a significantly better survival rate than the primary implant [p 0.008; hazard ratio (HR) = 5.87, 95 % CI 1.57–21.90]. The variables of age, ASA classification and sex were not significant confounders. The variable of indication for rTKA because of sepsis appeared to be a significant confounder. After adding this confounder into the Cox regression analysis, use of a revision implant during rTKA showed a significantly better survival rate than implantation of a primary implant (p 0.039; HR = 4.56, 95 % CI 1.08–19.27) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Survival of revision implants. Implants were divided into two groups: primary implants and revision implants. Covariate septic or aseptic indication for revision was added in this Cox regression analysis

A total of nine re-operations were assessed in this study. Four primary implants underwent a re-rTKA. Indications were aseptic loosening in two cases and infection in two cases. Five revision implants underwent re-operation. Three re-rTKAs, one amputation and one arthrodesis were performed. Indications for re-rTKA were aseptic loosening, infection and instability in one case each. Indication for amputation was chronic pain, and infection was the reason for arthrodesis.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate survival of primary and revision implants. Over the past two decades, there has been an increase in rTKAs [3] performed, and a further increase is predicted [4]. This has heightened the interest in rTKA and factors that influence the outcome of this procedure. During rTKA, primary and revision implants are used to restore the knee joint. However, little is known about the survival rate of both types of implants following rTKA and whether implanting a primary implant during rTKA is a good option. This study was conducted to compare survival rates of primary implants with revision implants when implanted during rTKA. Our results show that a primary implant used during rTKA suffers a significantly worse survival rate compared with a revision implant during the revision operation. Overall survival of implants, with repeat rTKA defined as the endpoint, was 96 % at one year, 89 % at two years and 85 % at five years. These results are comparable with rTKA survival in Finland between 1990 and 2002, which showed rates of 95 % at two years, 89 % at five years and 79 % at ten years [18]. Other, generally older, studies report failure rates or poor results of 19–63 % for follow-up periods of five years or more [22–25].

In this study, five of the 60 revision implants and four of the nine primary implants underwent a further rTKA. For revision implants, one of the five further rTKAs was performed for aseptic loosening. For primary implants, two of the four additional rTKAs were performed because of aseptic loosening. Several clinical studies suggest that more constraint leads to earlier aseptic loosening because of more implant–cement–bone stress [8, 13]. A characteristic of a revision implant is more constraint; hence, one might expect a higher rate of aseptic loosening. However, in this study, the frequency of aseptic loosening was significantly higher in the group that received a primary implant. Indications for using a primary implant in rTKA are minimal ligament and bone damage. It is possible that these two factors are underestimated in this group of patients. When a primary implant is implanted and more constraint and augmentations are required, this may lead to diminished fixation of prosthesis components to bone, earlier aseptic loosening and thus re-revision. Therefore, it may be questionable whether using a primary implant should be even an option in rTKA, as bone and ligament damage are usually extensive. Which type of revision implant should be advised for what degree of bone and ligament damage is a subject for further study.

Several investigators report that results of septic rTKAs are inferior to aseptic revision [26–30]. In five of the nine revisions where primary implants were used, the reason for revision was infection. In the group of revision implants in our study, 16 of the 60 were done because of an infection; therefore, corrections were made during the survival analysis for septic or aseptic indication.

A strong point of this study is that it adds new knowledge to the scarce literature on survival of primary implants in revision arthroplasty. However, this study also has some limitations. Firstly, a selection bias must be present. Restoration of a knee joint with major ligamental damage and bone loss is a complex procedure. In these cases, a revision implant is always performed. When bone loss and ligamental damage are limited, i.e. cases of Anderson Orthopaedic Research Institute (AORI) type I defects [31], the surgical procedure is less complex, and one can choose between either a primary or revision implant. Consequently, primary implants are always used in less complex revision operations, whereas revision implants are also commonly used in more difficult procedures. Secondly, with respect to Cox regression analyses, it is assumed that observations are independent of each other. However, four patients in this study underwent bilateral rTKA, and survival analyses were carried out without taking bilaterality into account. Robertsson et al. reported that the effect of not accounting for bilaterality in knee revision surgery is minute and that the risk of revision of knee implants can be analysed without consideration for subject dependency [32]. Finally, it can be argued that a limited number of patients was available. Revision surgery is a difficult procedure, and this type of surgery is only performed in specialised centres. Therefore, implant survival at one, two and five years has a wide confidence interval. Because a growing number of rTKAs is expected, future studies with larger series are necessary to gain more insight into long-term survival and factors that influence rTKA outcome.

Overall, it can be concluded that despite the relatively small number of patients in this study, primary implants implanted during rTKA have a significantly worse survival rate than revision implants. Choosing the right type of implant in rTKA is a challenging task. Based on results of this study, it has to be considered whether primary implants are even an option during rTKA.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

Drs. A.L. Boerboom is a paid consultant for Zimmer GmbH for training in knee arthroplasty and computer-assisted surgery. The department receives research institutional support from Stryker and Zimmer. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Kurtz S, Mowat F, Ong K, Chan N, Lau E, Halpern M. Prevalence of primary and revision total hip and knee arthroplasty in the united states from 1990 through 2002. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1487–1497. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Widmer M, Maravic M, et al. International survey of primary and revision total knee replacement. Int Orthop. 2011;35:1783–1789. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1235-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nevalainen J, Keinonen A, Mäkelä A, Pentti A (2003) The 2002–2003 implant yearbook on orthopaedic endoprostheses: Finnish arthroplasty register. helsinki, finland: National agency for medicines. www.nam.fi/uploads/julkaisut/Orthopaedic_endoprostheses_2003_v.pdf

- 4.Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the united states from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:780–785. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryan RS, Rand JA. Revision total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;170:116–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whiteside LA. Cementless revision total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;286:160–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hwang SC, Kong JY, Nam DC, Kim DH, Park HB, Jeong ST, Cho SH. Revision total knee arthroplasty with a cemented posterior stabilized, condylar constrained or fully constrained prosthesis: a minimum 2-year follow-up analysis. Clin Orthop Surg. 2010;2:112–120. doi: 10.4055/cios.2010.2.2.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morgan H, Battista V, Leopold SS. Constraint in primary total knee arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13:515–524. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200512000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peters CL, Hennessey R, Barden RM, Galante JO, Rosenberg AG. Revision total knee arthroplasty with a cemented posterior-stabilized or constrained condylar prosthesis: a minimum 3-year and average 5-year follow-up study. J Arthroplasty. 1997;12:896–903. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(97)90159-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scuderi GR. Revision total knee arthroplasty: how much constraint is enough? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;392:300–305. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200111000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pour AE, Parvizi J, Slenker N, Purtill JJ, Sharkey PF. Rotating hinged total knee replacement: use with caution. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1735–1741. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sculco TP. The role of constraint in total knee arthoplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:54–56. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2006.02.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartford JM, Goodman SB, Schurman DJ, Knoblick G. Complex primary and revision total knee arthroplasty using the condylar constrained prosthesis: an average 5-year follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:380–387. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(98)90002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Callaghan JJ, O’Rourke MR, Liu SS. The role of implant constraint in revision total knee arthroplasty: not too little, not too much. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:41–43. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuckler JM. Revision total knee arthroplasty: how much constraint is necessary? Orthopedics. 1995;18(932–3):936. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19950901-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gustke KA. Preoperative planning for revision total knee arthroplasty:avoiding chaos. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:37–40. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulhall KJ, Ghomrawi HM, Engh GA, Clark CR, Lotke P, Saleh KJ. Radiographic prediction of intraoperative bone loss in knee arthroplasty revision. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;446:51–58. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000214438.57151.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheng PY, Konttinen L, Lehto M, Ogino D, Jamsen E, Nevalainen J, Pajamaki J, Halonen P, Konttinen YT. Revision total knee arthroplasty: 1990 through 2002. A review of the finnish arthroplasty registry. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1425–1430. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meding JB, Wing JT, Ritter MA. Does high tibial osteotomy affect the success or survival of a total knee replacement? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:1991–1994. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1810-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ranawat CS, Flynn WF, Jr, Deshmukh RG. Impact of modern technique on long-term results of total condylar knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;309:131–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc Series B. 1972;34:182–202. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rand JA, Bryan RS. Revision after total knee arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 1982;13:201–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldberg VM, Figgie MP, Figgie HE, 3rd, Sobel M. The results of revision total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;226:86–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cameron HU, Hunter GA. Failure in total knee arthroplasty: mechanisms, revisions, and results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;170:141–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanssen AD, Rand JA. A comparison of primary and revision total knee arthroplasty using the kinematic stabilizer prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70:491–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barrack RL, Engh G, Rorabeck C, Sawhney J, Woolfrey M. Patient satisfaction and outcome after septic versus aseptic revision total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15:990–993. doi: 10.1054/arth.2000.16504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deehan DJ, Murray JD, Birdsall PD, Pinder IM. Quality of life after knee revision arthroplasty. Acta Orthop. 2006;77:761–766. doi: 10.1080/17453670610012953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang CJ, Hsieh MC, Huang TW, Wang JW, Chen HS, Liu CY. Clinical outcome and patient satisfaction in aseptic and septic revision total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2004;11:45–49. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0160(02)00094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mortazavi SM, Molligan J, Austin MS, Purtill JJ, Hozack WJ, Parvizi J. Failure following revision total knee arthroplasty: infection is the major cause. Int Orthop. 2011;35:1157–1164. doi: 10.1007/s00264-010-1134-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zywiel MG, Johnson AJ, Stroh DA, Martin J, Marker DR, Mont MA. Prophylactic oral antibiotics reduce reinfection rates following two-stage revision total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2011;35:37–42. doi: 10.1007/s00264-010-0992-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Engh GA, Ammeen DJ. Bone loss with revision total knee arthroplasty: defect classification and alternatives for reconstruction. Instr Course Lect. 1999;48:167–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robertsson O, Ranstam J. No bias of ignored bilaterality when analysing the revision risk of knee prostheses: analysis of a population based sample of 44,590 patients with 55,298 knee prostheses from the national Swedish Knee Arthroplasty register. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2003;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]