Abstract

Knowledge of blood 1H2O T1 is critical for perfusion-based quantification experiments such as arterial spin labeling (ASL) and CBV-weighted MRI using vascular space occupancy (VASO). The dependence of blood 1H2O T1 on hematocrit fraction (Hct) and oxygen saturation fraction (Y) was determined at 7 Tesla using in vitro bovine blood in a circulating system under physiological conditions. Blood 1H2O R1 values for different conditions could be readily fitted using a two-compartment (erythrocyte and plasma) model which are described by a monoexponential longitudinal relaxation rate constant dependence. It was found that T1 = 2171±39 ms for Y = 1 (arterial blood) and 2010±41 ms for Y = 0.6 (venous blood), for a typical Hct of 0.42. The blood 1H2O T1 values in the normal physiological range (Hct from 0.35 to 0.45, and Y from 0.6 to 1.0) were determined to range from 1900 ms to 2300 ms. The influence of oxygen partial pressure (pO2) and the effect of plasma osmolality for different anticoagulants were also investigated. It is discussed why blood 1H2O T1 values measured in vivo for human blood may be about 10-20% larger than found in vitro for bovine blood at the same field strength.

Keywords: longitudinal relaxation; in vitro blood; 7T; hematocrit; oxygen saturation fraction; oxygen partial pressure; mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; plasma osmolality,

INTRODUCTION

The longitudinal relaxation time constant (T1) of blood water protons (1H2O) serves as an important MR parameter for a number of quantitative MRI applications, such as arterial spin labeling (ASL) for estimating cerebral blood flow (CBF) (1), and vascular space occupancy (VASO)-dependent MRI for detecting cerebral blood volume (CBV) weighted signal changes (2).

Whole blood is composed largely of erythrocytes (red blood cells, or RBCs) and plasma. Blood has two primary protein constituents, namely intracellular hemoglobin (mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration or MCHC of 33-34 g/dL, or ~5 mM (mmol Hb tetramer / L plasma in the erythrocyte)) and extracellular albumin with concentration of ~5 g/dL, or ~0.75 mM (mmol Alb / L plasma), respectively (3) (see Table 1 for unit conversions). The hematocrit fraction (Hct, erythrocyte volume fraction) is a major contributor to spin-lattice relaxation of blood: higher Hct decreases T1 (4,5). Hemoglobin oxygenation is not much of a factor at lower fields, but at fields above 1.5T, lower oxygen saturation fraction (Y) has been shown to reduce blood 1H2O T1 (1.5T, (6); 3.0T: (7); 4.7T: (8)). Under conditions of 100% O2 in a perfusion system, excessive O2 (a weak paramagnetic molecule) is dissolved into the plasma, leading to elevated oxygen partial pressure (pO2) and decreased blood 1H2O T1 (8).

Table 1.

Protein concentrations within plasma and erythrocyte used in this paper.

| molecular weight (kDa or g/mmol) |

conversion factor (mmol/g · dL/L) |

concentration (g/dL) |

concentration (mmol/L) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albumin, or Alb (Plasma) |

66.463 | 0.1505 | 5 | 0.75 |

| Hemoglobin, or Hb (Erythrocyte) |

16.425 (monomer) |

0.6088 | 33.86 | 20.60 (monomer) |

| 65.700 (tetramer) |

0.1522 | 5.15 (tetramer) |

Blood 1H2O T1 values have previously been reported at 1.5T (2,6,9-11), 3T (7,12-15), 4.7T (8,16,17), 7T (11,17), 9.4T (17), and 11.7T (18) and, similar to other tissues, increase with field strength (11,19). Although 7T instruments have been widely adopted for pre-clinical imaging of small animals, and are increasingly becoming available for human research, only limited reports of blood 1H2O T1 values are available, either with a narrow range of Hct and Y (17) or without these physiology parameters reported (11). In this work, we quantified blood 1H2O T1 at 7T for a wide range of conditions to account for the effects of Hct, Y, pO2, and plasma osmolality at physiological temperature and pH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Blood Preparation

Bovine blood, obtained from a local slaughterhouse, was used because it has similar water permeability as human blood (20) and is readily available. Fresh blood samples were treated with 25 mM trisodium citrate to prevent coagulation, stored at 4°C, and used within 8 days. Erythrocytes and plasma were prepared by centrifuging the whole blood at 10,000 rpm for 15 min, and recombined to make blood samples with a range of Hct values (0.31, 0.45, 0.56, 0.63, 0.75). Erythrocyte sedimentation rates (as a measure of how quickly RBCs settle in a test tube in one hour) of normal blood are in the range of 10-30 mm/hr (3). In order to avoid sedimentation of erythrocytes, blood samples (~350 ml) were pumped into a loop at a flowing speed of about 30 ml/min (~0.5 cm/s). The circulation pump was only stopped during the T1 measurements to minimize flow artifacts (~ 2.5 min for the whole blood experiment; ~ 3.1-3.8 min for the plasma experiment, for TR = 16s versus 20s, respectively. Details are described below). For each experiment, T1 measurement started right after the pump was stopped. During the 2.5 min after stopping the circulation pump for the whole blood experiment, the effect of precipitation of RBCs is relatively small (Figure 1 of (10)). For whole blood at each Hct, four different Y-values ranging between 0.45 or 0.5 and 0.9 were reached by bubbling nitrogen and oxygen gas into a mixing chamber that was part of a closed circulation loop. Blood was sampled right before and after the MR measurements, and Hct and oxygenation (both Y and pO2) were determined using a blood gas analyzer (Radiometer, ABL700). Note that Hct value reported by the blood gas analyzer was calculated using an empirical formula: Hct = 0.0485 (L plasma in erythrocyte / mmol Hb monomer) ctHb (mmol Hb monomer / L blood) + 0.0083 for the Hb monomer (ctHb: the concentration of hemoglobin in blood and ctHb = MCHC · Hct). This corresponds to a standardized MCHC of 33.86 g/dL, or 20.6 mM (mmol Hb monomer / L plasma in erythrocyte) using a hemoglobin mass of 16.425 (g/mmol) for the monomer (Table 1). Temperature of the circulating blood inside the magnet was maintained at approximately 37°C by water bath. The temperature was calibrated using a fiber-optic thermo-sensor (Oxford Optronix) before the experiments and pO2 was monitored during the experiments by a fiber-optic pO2-sensor (Oxford Optronix) placed outside of the RF coil. The 1 cm-diameter, 10 cm-long sample tube (middle part of the circulation loop) was vertically positioned through a hard foam fixed inside the coil. Two saline bags were put above the foam to load the RF coil. The procedure and setup are similar to previous experiments performed in our lab (7,21).

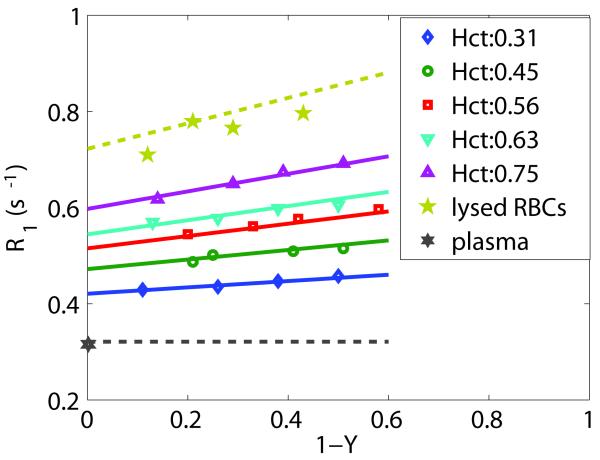

Figure 1.

Longitudinal relaxation rate constant (R1,blood) at five hematocrit fractions and four deoxygenation levels (1-Y) were fitted using the two-compartment model in the fast-exchange-limit condition of Eqs. [2]-[4] (solid lines). The fitted R1 values for erythrocyte water show a linear dependence on (1-Y), while plasma was assumed constant through (1-Y) (black dashed lines). The resulting R1,ery(Y) (chartreuse dashed line) and R1,plasma compare well to results from separate experiments on lysed RBCs (pentagrams) with 4 different oxygenations, and plasma (hexagram) with pO2 of 87 mmHg. The experimental data point for plasma was arbitrarily placed at 1-Y = 0.

Plasma sample was also measured. By bubbling nitrogen gas into the mixing chamber, the plasma pO2 level was adjusted from about 160 mmHg (21% of atmospheric pressure at sea level) down to about 60-110 mmHg, which is the normal pO2 range in the systemic arterial blood (3).

In order to estimate the intrinsic relaxation time constants of water within an erythrocyte, samples of lysed blood were prepared: 300 ml of packed blood cells at different oxygenation levels were lysed in aliquots of 100 ml by sonication on ice for 6 min. with an amplitude of 45% in cycles of 10 sec ”on” and 5 sec “off”, using a flat tip horn by Branson Ultrasonics (Danbury, CT, USA). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 15 min at 4°C, and the cell lysate was immediately used for NMR measurements. The concentration of hemoglobin in lysed blood was in the range of 33.0-34.6 g/dl, i.e. similar to the concentration of hemoglobin in an erythrocyte (~34 g/dL). It was important to keep the time between cell lysis and data acquisition as short as possible, because of increased formation of paramagnetic methemoglobin in lysed blood. Cell lysis triggers mechanisms that significantly slow down natural methemoglobin reduction to oxygen-carrying hemoglobin (22) and this effect is even greater in bovine blood. Measured metHb levels in lysed blood were between 1.8-2.4% (23). Four different oxygenation levels between 0.5 and 0.9 were achieved to allow measurements of the T1 dependence on deoxygenation (1-Y).

In a separate experiment, effects of pO2 and plasma osmolality on blood 1H2O T1 were investigated. Three blood samples (Hct = 0.44) were prepared with different anticoagulants: 52 Units/mL lithium heparin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO); 25 mM trisodium citrate (as above); 50 mM trisodium citrate. For each blood sample, two to three oxygenation levels were achieved that simulated the deoxygenated blood (Y ~ 0.7, pO2 ~ 40 mmHg), oxygenated blood (Y = 1.0) with physiological pO2 (60-110 mmHg) and with much elevated pO2 (250-300 mmHg). Sodium concentration and the plasma osmolality of each sample were determined using the blood gas analyzer.

MR Methods

The MR experiments were conducted on a 7T whole-body scanner (Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands), using a quadrature head coil for both RF transmission and reception. Conventional inversion recovery sequence was performed for T1 measurement using a non-selective adiabatic inversion pulse (hyperbolic secant pulse (24), length 8.6 ms, peak power 15 μT, and bandwidth 1500 Hz). A total of 10 inversion delay times (TI = [100, 400, 700, 1000, 1400, 1900, 2500, 4000, 6000, 9000] ms) were sampled. To minimize possible radiation damping effects (7,25,26), a small dephasing gradient (0.6 mT/m) was applied continuously during the inversion delay time. Axial slice-selective excitation pulse (slice thickness = 10 mm) was utilized to only obtain signals from a central region of the tubing where relatively homogeneous B0 field and B1 field were expected. A local volume covering the slice of interest was shimmed. At 7T, T2* of venous blood has been reported to be about 10 ms or less (27). To reduce signal loss from the small T2*, 1D gradient-echo profile acquisition at the shortest possible TE was employed (FOV = 64 mm, 2 mm acquisition resolution in the axial plane with 32 read-out points acquired, TE = 2 ms). Right after image acquisition, a constant recovery time (12 s for whole blood; 16 s or 20 s for plasma) was inserted before the next inversion pulse to ensure a return to equilibrium magnetization (~5 T1). The total measurement time was about 2.5 min for each specific Hct, Y, and pO2 condition of the whole blood, and 3.8 min for each pO2 condition of the plasma experiment.

Data Analysis

Matlab 7.0 (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA) was used for data processing. Averages of the magnitude intensities at the center of the slice profiles were fitted as a function of TI using a 3-parameter model that applies at long TR:

| [1] |

The equilibrium magnetization S0, the constant C (related to inversion efficiency and recovery time), and the blood 1H2O T1 were fitted using a nonlinear-least-squares algorithm of Matlab (lsqcurvefit).

A model of two compartments (erythrocyte/plasma) in which the contributing relaxation rates are volume averaged was used to express the longitudinal relaxation rate constant (R1) of whole blood as a function of Hct. Notice that this volume averaging is mathematically equivalent to a “fast exchange” solution, which is allowed because the difference in longitudinal relaxation rates R1,ery - R1,plasma, (also called the shutter speed (28,29)) is much smaller than the exchange rate between the two compartments (See appendix). It is important to point out that this fast exchange for longitudinal relaxation is not the same as for transverse relaxation, which relates to resonance averaging in the NMR spectrum. Here, depending on oxygenation level and field strength, the transverse relaxation situation may vary between fast and intermediate exchange. Thus, for some oxygenations the intracellular and extracellular water signals may have separate but partially overlapping resonances that cannot be visually separated in the NMR spectrum due to their linewidths. However, experimental results and theory (Appendix) indicate that the inversion recovery experiment can be described by a single rate constant for blood corresponding to the volume averaged contribution over plasma and erythrocyte water. Thus:

| [2] |

R1,ery and R1,plasma are the compartmental R1 values. fery,water is the fraction of water in the whole blood that resides inside erythrocytes. Under physiological conditions, water content in the erythrocytes has been measured to be about 70% (30). Hemoglobin volume fraction has also been approximated as 30% of the interior cell volume (31). Water volume fraction in plasma was taken to be 94-95% (8,10). In line with this, we assumed that 70% of erythrocyte volume and 95% of plasma is water, and used the following Equation to relate fery,water with Hct (8,10,31):

| [3] |

Deoxyhemoglobin is a weak paramagnetic contrast agent, and R1,ery can be approximated to be linearly related to the deoxygenation fraction (1-Y) with r1,deoxyHb as the molar relaxivity (s−1 · L plasma in erythrocyte / mmol Hb tetramer) of the agent (8,16):

| [4] |

where [Hb] is the MCHC in (mmol Hb tetramer / L plasma in erythrocyte).

Data fitting to this model (Eqs. [2],[3],[4]) was performed using multivariate nonlinear-least-squares curve fitting method from Matlab (lsqnonlin) across four different deoxygenation fractions at each of the five Hct values (an overdetermined system with 20 data points and 3 unknowns: r1,deoxyHb, R1,ery(Y=1) and R1,plasma). In addition, the 95% confidence interval was calculated for each estimated parameter using a Matlab function (nlparci). In order to verify the fitting model, R1 values measured from plasma samples were compared to the fitted R1,plasma. Using the three fitted unknowns and their respective 95% confidence intervals, the uncertainties of other relaxation values that were calculated using above model (Eqs. [2],[3],[4]) were estimated based on the error propagation.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Figure 1 illustrates the measured linear dependency of blood R1 on deoxygenation (1-Y). Data for five Hct values (0.31, 0.45, 0.56, 0.63, and 0.75) were fitted together to Eqs. [2], [3], [4] using multivariate fitting (solid lines). The estimated parameters with corresponding 95% confidence intervals are listed in Table 2. These parameters were used to estimate the relaxation rate constant dependencies on deoxygenation for erythrocyte water and pure plasma, which are also displayed in Figure 1 (dashed lines):

| [5a] |

| [5b] |

These data estimated from the fitting compare well with measured R1s of lysed blood (with hemoglobin concentration similar to MCHC) at different deoxygenation levels (pentagram) and the measured R1,plasma of 0.322 (s−1) (hexagram) for a physiological condition with pO2 of 87 mmHg (Table 3).

Table 2.

Fitted Parameters from the Two-Compartment Model in the Fast-Exchange-Limit Condition of R1,biood at various Hct and Y.

| r1,deoxyHb (s−1 · L plasma in erythrocyte / mmol Hb tetramer ) |

R1,ery(Y=1) (s−1) |

R1,plasma (s−1) |

T1,ery(Y=1) (ms) |

T1,plasma (ms) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| estimated value | 0.052 | 0.722 | 0.321 | 1385 | 3114 |

| 95% confidence interval |

[0.045, 0.061] | [0.705, 0.739] | [0.312, 0.330] | [1352, 1417] | [3026, 3201] |

Table 3.

Effects of pO2 and Plasma Osmolality on T1 of Whole Blood and Plasma.

| Anticoagulant conc. |

Osmolality (mOsm·kg−1) |

Y | pO2 (mmHg) |

R1 (s−1) |

T1 (ms) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Blood (Hct = 0.45a) | ||||||

| Li+ heparin | 52 units/mL | 264 | 0.72 | 37 | 0.469 | 2133 |

| 1 | 62 | 0.456 | 2199 | |||

| 1 | 280 | 0.491 | 2037 | |||

| 3Na+ citrate | 25 mM | 381 | 0.74 | 42 | 0.473 | 2115 |

| 1 | 109 | 0.462 | 2163 | |||

| 1 | 273 | 0.499 | 2003 | |||

| 3Na+ citrate | 50 mM | 517 | 0.73 | 44 | 0.505 | 1979 |

| 1 | 262 | 0.527 | 1898 | |||

| Plasma | ||||||

| 3Na+ citrate | 25 mM | 374 | N/A | 87 | 0.322 | 3104 |

| N/A | 107 | 0.330 | 3028 | |||

| N/A | 167 | 0.339 | 2948 | |||

Hct value reported by the blood gas analyzer was based on a standardized MCHC of 33.86 g/dL. So it does not reflect the higher MCHC and the lower Hct expected with the higher plasma osmolality.

As summarized in a review paper on blood relaxation (4), T1 relaxation times of RBCs containing only oxyhemoglobin or plasma with albumin are affected largely by diamagnetic relaxation. However, it has to be realized that the presence of proteins still leads to faster relaxation of water protons because of increased rotational correlation times due to increased viscosity and the interaction (binding, magnetization transfer, exchange) of the water protons with the slow macromolecules. Slowed rotational motion leads to faster relaxation, as originally explained by Bloembergen et al. (32). The measured intrinsic relaxation rate constants of oxygenated erythrocytes and plasma, R1,ery(Y=1) = 0.722±0.017 s−1 and R1,plasma = 0.321±0.009 s−1 (T1: 1385±32 ms vs. 3114±87 ms), are therefore likely to be primarily influenced by the protein concentrations in each compartment through the relaxivity effects of macromolecular binding and concomitant slower tumbling, which can be expressed as (11):

| [6a] |

| [6b] |

R1’ is the relaxation rate constant for pure saline at physiological temperature and equals 0.222 s−1 (T1’ = 4500 ms) (33). With typical hemoglobin concentration of 5.15 mM (mmol Hb tetramer / L plasma in erythrocyte) and typical albumin concentration of 0.75 mM (mmol Alb / L plasma) (Table 1), the corresponding molar relaxivities for macromolecular site are r1,Hb = 0.097±0.003 s−1(mmol Hb tetramer / L plasma in erythrocyte) −1 and r1,Alb = 0.132±0.012 s−1 (mmol Alb /L plasma)−1, respectively. These two macromolecular site relaxivities are close, as expected, given that hemoglobin tetramer and albumin have similar size and molecular weight (Table 1). It is worth noting that in some pathological conditions such as anemia, protein concentrations in blood may change significantly or other protein levels may be elevated remarkably. A higher protein concentration within the RBCs can itself enhance the relaxation of the whole blood, without the change of Hct.

The slope describing the oxygenation dependence of R1,ery(Y) at 7T is 0.265±0.040 s−1 (Eq. [5a]). When using the hemoglobin concentration of 5.15 mM (mmol Hb tetramer / L plasma in erythrocyte), this gives a molar relaxivity for deoxyhemoglobin, r1,deoxyHb, of 0.0515±0.008 s−1(mmol deoxyHb tetramer / L plasma in erythrocyte) −1 (Eq. [4]). At 4.7T, the slope of R1,ery(Y) was fitted to be 0.6 s−1 (8) and corresponding to 0.117 s−1(mmol deoxyHb tetramer / L plasma in erythrocyte)−1. Another study at 4.7T performed at room temperature reported r1,deoxyHb as 0.20 s−1(mmol deoxyHb tetramer / L plasma in erythrocyte)−1 (16). As expected, the molar relaxivity of deoxyhemoglobin was slightly lower at 7T than at 4.7T. Based on the molar relaxivity of Gadolinium-based contrast agents measured at 7T with a range of 3-6 s−1·mM−1 (34) and the molar relaxivities of hemoglobin and albumin calculated above for macromolecular binding, it can be concluded that deoxyhemoglobin is a very mild paramagnetic T1 relaxation agent.

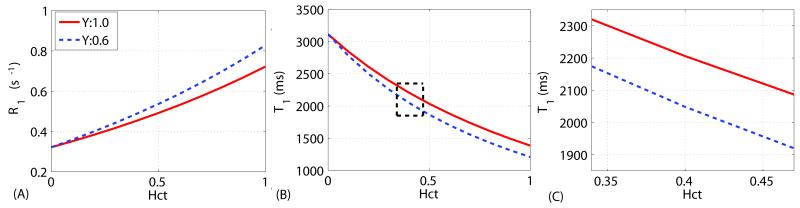

To visualize the Hct dependence of blood R1 at 7T, R1 values at Y = 1 (arterial) and Y = 0.6 (venous) with varying Hct can be calculated from the data in Table 2:

| [7] |

| [8] |

These dependencies are shown in Figure 2A. For convenience, the T1 (inverse R1) curves with regard to Hct are shown in Figure 2B, and zoomed out in Figure 2C for a 0.34 to 0.47 physiological Hct range (3). For Y=1 (arterial oxygenation), blood 1H2O T1s are estimated to be 2298±43 ms and 2119±38 ms for Hct = 0.35 and 0.45. At a typical human Hct of 0.42, the arterial and venous T1s are 2171±39 ms and 2010±41 ms. At this high field strength, the arterial-venous T1 difference (161 ms) is getting close to the T1 difference over the Hct range from 0.35 – 0.45 (179 ms), which was not the case at lower fields (≤ 3T).

Figure 2.

(A) Dependence of the longitudinal relaxation rate constant (R1,blood) on Hct: Eq. [7] for Y = 1 (arterial blood) and Eq. [8] for Y = 0.6 (venous blood), respectively. (B) Corresponding plots for T1,blood. (C) Zoomed display of the T1,blood curves within the possible physiological range of Hct.

Blood 1H2O T1 results for various pO2 and plasma osmolality are reported in Table 3. In all three samples with different concentration of anticoagulant, blood 1H2O T1 values were the highest at Y = 1.0, compared to both the deoxygenated condition (Y ~ 0.73) and the oxygenated condition with Y = 1.0 and pO2 in the 250-300 mmHg range). As well known, the oxygen-hemoglobin dissociation curve, Y (y axis) related to pO2 (x axis), follows a sigmoidal shape (3). Hemoglobin's affinity for oxygen (Y) increases with higher pO2 until it reaches the plateau part of the curve, where the hemoglobin is fully saturated with oxygen (Y = 1). For Y < 1, the enhanced longitudinal relaxation is largely due to the paramagnetic effect of deoxyhemoglobin and a function of (1-Y); At Y = 1, it is primarily influenced by the paramagnetic oxygen molecule dissolved in blood plasma and is linearly dependent on pO2 (8). Similarly (Table 3), the plasma T1 values were lower with higher pO2.

Normal sodium levels in plasma are about 135-145 mM, which corresponds to a normal plasma osmolality for blood of 300 mOsm/kg (3). Higher plasma sodium concentrations draw water out of the erythrocytes via osmosis, causing shrinkage of the red blood cells, and leading to the serious clinical condition of “hypernatremia” (3). In our in vitro blood relaxation studies, we usually add 20-25 mM trisodium citrate into the fresh bovine blood to prevent coagulation. In Table 3, no significant changes of blood 1H2O T1 were found between blood added with lithium heparin and with 25 mM trisodium citrate. The higher plasma osmolality (517 mOsm/kg) induced by the higher concentration of sodium ions (50 mM trisodium citrate) decreased blood 1H2O T1 (Table 3). For blood with the two trisodium citrate concentrations (25 and 50 mM, respectively), the R1 values at Y ~ 0.73 and Y = 1 with pO2 ~ 270 mmHg give about 0.030 s−1 difference per 25 mM. At the Y = 1 with pO2 ~ 100 mmHg (arterial blood condition), the R1 value of blood without any addition of anticoagulant can be extrapolated to 0.432 s−1 vs 0.462 s−1 (25 mM trisodium citrate), when assuming a linear dependence. With regard to T1 values, this would correspond to 2315 ms without anticoagulant, instead of 2163 ms with 25 mM trisodium citrate, about 150 ms larger.

The blood 1H2O T1 values in the normal physiological range (Hct from 0.35 to 0.45, and Y from 0.6 to 1.0) determined in this study, 1900 ms to 2300 ms (Figure 2C), are close to the value of 2212 ms (Hct ~ 0.43, Y ~ 0.79) reported in (17), which is not surprising in view of the similar experimental setups (bovine blood phantom in a circulating system maintained at 37°C). In another report at 7T, T1 measured in sagittal sinus of normal male subjects was about 2600 ms (11), about 15-20% larger than what we report here. This result compares well with our findings at 3T, where blood 1H2O T1 values measured in vivo in humans were also about 10-20% larger than found in vitro for bovine blood (14). The amount of anticoagulant added to the blood when harvesting it may in part explain this difference, as explained above. Other factors that could potentially cause this discrepancy are not obvious, but probably also related to the differences between human and bovine blood or the way the hematocrit is reported. The blood analyzer employed in our experiments assumes a standardized MCHC of 33.86 g/dL, which is the one for human blood. The MCHC values reported for bovine blood range from 29 to 33 g/dL (35,36) and use of a higher MCHC by the blood gas analyzer would produce artificially lower Hct values for our data. If the actual bovine Hct were higher, the T1-Hct curves shown in Fig. 2(c) would shift to the right. Human Hct values at the same MCHC would be lower and thus have a higher T1. On the other hand, as reported above, the shrinkage of the RBCs due to additional sodium citrate would enhance T1 relaxation with higher protein concentration or lower water content inside the cells. This could explain part of the larger T1 found in vivo in humans. When using T1 of blood for determining CBF with ASL or the nulling time for VASO, it may be advisable to use values somewhat larger than these phantom experiments. Using a 15% increase, this would be 1913 ms at 3T and 2537 ms at 7T for blood of Hct ~ 0.4 and Y = 1.

In conclusion, we have measured the dependence of T1 on Hct and oxygenation for bovine blood at 7T, which fitted well to a two-compartment model under conditions of volume averaging of longitudinal relaxation rate constants. Within the physiological Hct range of 0.35-0.45, the blood 1H2O T1s spanned from 1900 ms to 2300 ms, with the oxygenation dependence between arterial and venous blood close to the Hct dependence over this range. The knowledge of these effects on blood 1H2O T1s is useful for quantitative perfusion and functional MRI applications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Joseph Gillen and Dr. Michael Schar (Philips) for experimental assistance. Dr. van Zijl is a paid lecturer for Philips Medical Systems. Dr. van Zijl is the inventor of technology that is licensed to Philips. This arrangement has been approved by Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies. This project was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering of the National Institutes of Health through Grant Number P41 EB015909.

Grant support from NIH P41 EB015909

APPENDIX

Time fractions and volume fractions for water

Exchange averaging is generally described in terms of lifetimes and time fractions. When using a two-compartment system, such time fractions are directly related to the volume fractions of the compartments due to mass balance requirements. For water in blood:

| [A1] |

in which keryis the unidirectional exchange constant for water leaving the erythrocyte and M is the magnetization. The magnetization is proportional to the water volume fraction in each compartment (see Eq. [3]) and the exchange rate is related to the lifetime.

| [A2] |

| [A3] |

The fraction of time that a water molecule spends in the erythrocyte is

| [A4] |

Combining equations [A1] – [A4], it can be derived that:

| [A5] |

Due to this equivalence of the time and volume fractions, we do not use the superscripts “time” and “vol” in the paper.

Fast and slow exchange terminology for T1 and T2

Fast exchange is generally thought of in terms of averaging of resonances of two exchanging sites due to the fact that the exchange rate of spins between the sites is much larger than the frequency difference between the resonances. However, this is just how fast exchange with respect to the difference of resonance frequencies and transverse relaxation is reflected in NMR spectra. A more general understanding of a fast exchange limit does not depend on the frequency difference between two resonances and can occur for situations where resonances are separated. Basically the requirement is that the exchange rate (inverse of the lifetime) is faster than the absolute difference between the relaxation rates for the individual compartments (37), also called the shutter speed by Springer et al. (28,29). In such a case, the ratio of the populations of the two compartments is never allowed to deviate from equilibrium and the two compartments relax as a unit with a common relaxation time. For blood, the interesting situation exists that the exchange regime for transverse relaxation can vary from fast to intermediate or to slow depending on the oxygenation fraction and the magnetic field strength used. The exchange regime for longitudinal relaxation, however, is in the fast limit under all of these conditions.

Using a lifetime of about 8 ms for water in the erythrocyte (based on the range τery ~ 6–9.6 ms in (38)), the lifetimes for water in plasma at multiple Hct values can be calculated using:

| [A6] |

>These range from 25 ms for Hct = 0.3 to 3.6 ms for Hct = 0.75. The lifetime for the two-compartment system is defined as:

| [A7] |

and thus ranges from 6.8 to 2.5 ms for Hct values of 0.3 to 0.75, respectively. Because the corresponding exchange rates (kexch = 1/τexch) of 147 and 400 Hz are much faster than the difference |R1,ery – R1,plasma| (< 1 Hz), the assumption of the fast exchange limit applies to the two compartment blood system with respect to the measurement of longitudinal relaxation rate constants. Notice however, that this does not mean that the water resonances for the erythrocyte and the plasma are indistinguishable. That visibility is determined by the relationship between the transverse relaxation time and the frequency difference between these two resonances, which depends on oxygenation and field strength.

Footnotes

Prepared for submission as a note in Magnetic Resonance in Medicine

REFERENCE

- 1.Detre JA, Leigh JS, Williams DS, Koretsky AP. Perfusion Imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1992;23(1):37–45. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910230106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu H, Golay X, Pekar JJ, van Zijl PCM. Functional magnetic resonance Imaging based on changes in vascular space occupancy. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50(2):263–274. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chanarin I, Brozovic M, Tidmarsh E, Waters D. Blood and its disease. Churchill Livingstone; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks RA, Dichiro G. Magnetic-Resonance-Imaging of Stationary Blood - a Review. Medical Physics. 1987;14(6):903–913. doi: 10.1118/1.595994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryant RG, Marill K, Blackmore C, Francis C. Magnetic-Relaxation in Blood and Blood-Clots. Magn Reson Med. 1990;13(1):133–144. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910130112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stefanovic B, Pike GB. Human whole-blood relaxometry at 1.5T: Assessment of diffusion and exchange models. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52(4):716–723. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu H, Clingman C, Golay X, van Zijl PCM. Determining the Longitudinal Relaxation Time (T1) of Blood at 3.0 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52(3):679–682. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silvennoinen MJ, Kettunen MI, Kauppinen RA. Effects of hematocrit and oxygen saturation level on blood spin-lattice relaxation. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49(3):568–571. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barth M, Moser E. Proton NMR relaxation times of human blood samples at 1.5 T and implications for functional MRI. Cellular and molecular biology (Noisy-le-Grand, France) 1997;43(5):783–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spees WM, Yablonskiy DA, Oswood MC, Ackerman JJH. Water proton MR properties of human blood at 1.5 Tesla: Magnetic susceptibility, T-1, T-2, T-2* and non-Lorentzian signal behavior. Magn Reson Med. 2001;45(4):533–542. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rooney WD, Johnson G, Li X, Cohen ER, Kim SG, Ugurbil K, Springer CS., Jr Magnetic field and tissue dependencies of human brain longitudinal 1H2O relaxation in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57(2):308–318. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanisz GJ, Odrobina EE, Pun J, Escaravage M, Graham SJ, Bronskill MJ, Henkelman RM. T-1, T-2 relaxation and magnetization transfer in tissue at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54(3):507–512. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu WC, Jain V, Li C, Giannetta M, Hurt H, Wehrli FW, Wang J. In Vivo Venous Blood T1 Measurement Using Inversion Recovery True-FISP in Children and Adults. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64(4):1140–1147. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qin Q, Strouse JJ, van Zijl PC. Fast measurement of blood T(1) in the human jugular vein at 3 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65(5):1297–1304. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varela M, Hajnal JV, Petersen ET, Golay X, Merchant N, Larkman DJ. A method for rapid in vivo measurement of blood T1. NMR Biomed. 2011;24(1):80–88. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer ME, Yu O, Eclancher B, Grucker D, Chambron J. Nmr Relaxation Rates and Blood Oxygenation Level. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34(2):234–241. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dobre MC, Ugurbil K, Marjanska M. Determination of blood longitudinal relaxation time (T-1) at high magnetic field strengths. Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;25(5):733–735. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin AL, Qin Q, Zhao X, Duong TQ. Blood longitudinal (T1) and transverse (T2) relaxation time constants at 11.7 Tesla. MAGMA. 2012;25(3):245–249. doi: 10.1007/s10334-011-0287-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomori JM, Grossman RI, Yuip C, Asakura T. Nmr Relaxation-Times of Blood - Dependence on Field-Strength, Oxidation-State, and Cell Integrity. Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography. 1987;11(4):684–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benga G, Borza T. Diffusional water permeability of mammalian red blood cells. Comp Biochem Physiol B-Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;112(4):653–659. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(95)00116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao JM, Clingman CS, Narvainen MJ, Kauppinen RA, van Zijl PCM. Oxygenation and Hematocrit dependence of transverse relaxation rates of blood at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58(3):592–597. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Power GG, Bragg SL, Oshiro BT, Dejam A, Hunter CJ, Blood AB. A novel method of measuring reduction of nitrite-induced methemoglobin applied to fetal and adult blood of humans and sheep. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103(4):1359–1365. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00443.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith JE, Beutler E. Methemoglobin formation and reduction in man and various animal species. The American journal of physiology. 1966;210(2):347–350. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1966.210.2.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silver MS, Joseph RI, Hoult DI. Highly Selective Pi/2 and Pi-Pulse Generation. J Magn Reson. 1984;59(2):347–351. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bloembergen N, Pound RV. Radiation Damping in Magnetic Resonance Experiments. Phys Rev. 1954;95:8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou J, Mori S, van Zijl PC. FAIR excluding radiation damping (FAIRER) Magn Reson Med. 1998;40(5):712–719. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910400511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yacoub E, Shmuel A, Pfeuffer J, Van De Moortele PF, Adriany G, Andersen P, Vaughan JT, Merkle H, Ugurbil K, Hu X. Imaging brain function in humans at 7 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2001;45(4):588–594. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yankeelov TE, Rooney WD, Li X, Springer CS., Jr Variation of the relaxographic "shutter-speed" for transcytolemmal water exchange affects the CR bolus-tracking curve shape. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50(6):1151–1169. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li X, Huang W, Morris EA, Tudorica LA, Seshan VE, Rooney WD, Tagge I, Wang Y, Xu J, Springer CS., Jr Dynamic NMR effects in breast cancer dynamic-contrast-enhanced MRI. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(46):17937–17942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804224105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kageyama K, Onoyama Y, Kogawa H, Goto E, Tanabe K. The maximum and minimum water content and cell volume of human erythrocytes in vitro. Biophysical chemistry. 1989;34(1):79–82. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(89)80044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gillis P, Peto S, Moiny F, Mispelter J, Cuenod CA. Proton Transverse Nuclear Magnetic-Relaxation in Oxidized Blood - a Numerical Approach. Magn Reson Med. 1995;33(1):93–100. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910330114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bloembergen N, Purcell EM, Pound RV. Relaxation Effects in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Absorption. Phys Rev. 1948;73(7):679–712. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zaharchuk G, Martin AJ, Rosenthal G, Manley GT, Dillon WP. Measurement of cerebrospinal fluid oxygen partial pressure in humans using MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2005;54(1):113–121. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noebauer-Huhmann IM, Szomolanyi P, Juras V, Kraff O, Ladd ME, Trattnig S. Gadolinium-based magnetic resonance contrast agents at 7 Tesla: in vitro T1 relaxivities in human blood plasma. Investigative radiology. 2010;45(9):554–558. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181ebd4e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rich GT, Sha'afi RI, Barton TC, Solomon AK. Permeability studies on red cell membranes of dog, cat, and beef. The Journal of general physiology. 1967;50(10):2391–2405. doi: 10.1085/jgp.50.10.2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jain NC. Essentials of Veterinary Hematology. Wiley-Blackwell; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 37.McLaughlin AC, Leigh JS., Jr Relaxation-Times in Systems with Chemical Exchange - Approximate Solutions for Nondilute Case. J Magn Reson. 1973;9(2):296–304. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herbst MD, Goldstein JH. A Review of Water Diffusion Measurement by Nmr in Human Red Blood-Cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;256(5):C1097–C1104. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1989.256.5.C1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]