Abstract

Purpose

Skin metastases of breast cancer remain a therapeutic challenge. Toll-like receptor 7 agonist imiquimod is an immune response modifier and can induce immune-mediated rejection of primary skin malignancies when topically applied. Here we tested the hypothesis that topical imiquimod stimulates local anti-tumor immunity and induces the regression of breast cancer skin metastases.

Methods

A prospective clinical trial was designed to evaluate the local tumor response rate of breast cancer skin metastases treated with topical imiquimod, applied 5 days/week for 8 weeks. Safety and immunological correlates were secondary objectives.

Results

Ten patients were enrolled and completed the study. Imiquimod treatment was well tolerated, with only grade 1-2 transient local and systemic side effects consistent with imiquimod's immunomodulatory effects. Two patients achieved a partial response (20%; 95% CI 3% - 56%). Responders showed histological tumor regression with evidence of an immune-mediated response, demonstrated by changes in the tumor lymphocytic infiltrate and locally produced cytokines.

Conclusion

Topical imiquimod is a beneficial treatment modality for breast cancer metastatic to skin/chest wall and is well tolerated. Importantly, imiquimod can promote a pro-immunogenic tumor microenvironment in breast cancer. Preclinical data generated by our group suggest even superior results with a combination of imiquimod and ionizing radiation and we are currently testing in patients whether the combination can further improve anti-tumor immune and clinical responses.

Keywords: imiquimod, toll-like receptor, breast cancer, chest wall recurrence, skin metastases

INTRODUCTION

Skin metastases of solid tumors remain a therapeutic challenge. Breast cancer is the second most common tumor, after melanoma, to metastasize to the skin [1, 2]. Breast cancer skin recurrence most frequently manifest after mastectomy and can present as firm nodules, diffuse infiltration or ulcerative lesions, often in proximity of the mastectomy scar. Initial management of recurrences usually includes resection and radiation, but skin metastases tend to recur and herald diffuse metastatic spread. Furthermore, cutaneous metastases affect quality of life and become a debilitating experience for the patient as progression of disease leads to chest wall ulceration, bleeding and super-infection. Therefore, novel treatment approaches are warranted.

Imiquimod is a synthetic imidazoquinoline and Toll-like receptor (TLR)-7 agonist [3]. TLRs are highly conserved pattern recognition receptors that alert the host to invading pathogens, thereby activating an innate immune response directly and an adaptive immune response, secondarily. TLR7 is located on endosomal membranes of antigen-presenting cells, including myeloid (mDCs) and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), monocytes, and macrophages. TLR7 activation induces secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, predominantly interferon (IFN)-α, interleukin (IL)-12, and tumor necrosis factor-α, and enhances DC maturation and antigen presentation [4]. This immunostimmulatory ability can be harnessed to promote anti-tumor immunity, either by applying the TLR agonist locally onto cancers or administering it as an adjuvant for cancer vaccines. Therefore TLR agonists are included in the ranked National Cancer Institute (NCI) list of immunotherapeutic agents with the highest potential to cure cancer [5, 6]. Imiquimod is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in a topical 5% formulation for the treatment of external genital warts, superficial basal cell carcinoma, and actinic keratosis. Topically applied, imiquimod exerts profound immunomodulatory effects on the tumor microenvironment leading to immune-mediated clearance of primary skin and mucosal malignancies [7, 8].

Based on imiquimod's efficacy in primary skin tumors and encouraged by anecdoctal reports of anti-tumor efficacy in skin metastases of melanoma and breast cancer [9, 10], we tested the hypothesis that treatment with topical imiquimod could induce the regression of breast cancer skin metastases. In a prospective phase II trial topical imiquimod 5% was applied to all cutaneous metastases and local anti-tumor activity and toxicity were measured after an 8-week treatment course. Tumor punch-biopsies were obtained before and after imiquimod treatment from each patient to study the immunological changes in the tumor microenvironment.

METHODS

Patient eligibility

Women ≥18 years of age with biopsy-proven breast cancer and measurable skin metastases (chest wall recurrence or skin metastases) not suitable for definitive surgical resection and/or radiotherapy, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 to 1, adequate bone marrow and organ function were eligible. Concurrent systemic cancer therapy (hormones, biologics or chemotherapy) was allowed to continue only if, on a stable regimen for ≥12 weeks, skin metastases did not respond. The trial required completion of prior radiotherapy and hyperthermia to the target area >4 weeks and >10 weeks respectively, prior to study entry. Systemic disease assessment by CT/PET-CT imaging pre- and post-treatment was not required by protocol and was left to the discretion of the treating physician. All patients provided a written informed consent for participation in this IRB-approved study (clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT00899574).

Trial design

The primary objective of this trial was to determine the local anti-tumor effect of topical TLR7 agonist imiquimod 5% cream in breast cancer patients with skin metastases. Secondary objectives were to assess toxicity and to study the immunological effects in the tumor microenvironment induced by imiquimod treatment. The trial was designed as an open label, single arm study to test the null hypothesis that the local anti-tumor effect (CCR and PR) was P≤0.05 versus the alternative that P≥0.20. An optimal two-stage Simon design was used, in which 10 patients were to be enrolled in stage one, with an expansion to stage 2 with an additional 19 patients if there was at least one responder in stage 1. The overall alpha level for this design was 0.047 with power of 0.801. At study entry, patient demographic and tumor characteristics (pathology, grade of differentiation, hormone receptor and human epidermal growth factor receptor (Her)-2 status), metastatic sites and treatment history were collected.

Treatment

Imiquimod 5% cream (Aldara™) was donated by Graceway Pharmaceuticals, LLC (Bristol, TN). The cream was self-applied by patients to all clinically apparent skin metastases for 5 days/week for 8 weeks (one cycle). Additional treatment cycles were left to the discretion of patient and treating physician. The cream was thinly spread onto the lesions, remained on the skin for approximately 8 hours overnight, and was washed off the following morning. One single use packet (containing 250 mg of the cream) was used to cover areas up to 100 cm2; another packet was used for each additional treatment area of 100cm2, up to a maximum of 6 packets per day. These dose determinations were based on extrapolation from clinical experience with dosing of up to 6 packets per application in patients with actinic keratoses [11, 12]. Imiquimod application was recorded by means of patient diaries and compliance was encouraged and monitored by weekly phone calls of study personnel to patients.

Response evaluation

Tumor assessment was performed by physical examination at baseline and after the 8-week treatment course; visible and/or palpable cutaneous metastases were outlined on transparent film and uploaded into the Image J computer program (version 1.42q, provided by the National Institutes of Health, USA) for digital calculation of the affected surface area (ROI, region of interest). Computer-aided image analysis of the ROI was compared before and after treatment to assess response. As chest wall/skin lesions can be multifocal, confluent and highly irregular, response criteria for this study were chosen based on criteria established for chest wall tumors by the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) modified from assessment of Kaposi's sarcoma skin lesions [13]. These response criteria are defined as follows: complete clinical response (CCR, absence of any detectable residual disease), partial response (PR, residual disease less than 50% of original tumor size), stable disease (SD, 50-99% of original tumor size), no response (NR, 100-124% of original tumor size) and progressive disease (PD, 125% or greater of original tumor size or new skin lesions).

Tumor biopsies and immune analyses

Tumor biopsies (4mm diameter punch) were obtained at baseline and after imiquimod treatment (3-5 days after completing an 8 week treatment cycle) from each patient. Each biopsy specimen was bisected; one half was processed into paraffin-embedded tissue for subsequent immunohistochemical staining and the other half was cultured for analysis of tumor supernatant as well as for characterization of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed on formalin fixed, paraffin embedded tumor tissues. Tissue sections (thickness 4 micron) were deparaffinizied and rinsed in distilled water. Heat induced epitope retrieval was performed in 10mM citrate buffer pH 6.0. CD3, CD4 and CD8 antibodies (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ) were ready to use and undiluted; Forkhead Box Protein P3 antibody (FoxP3, Ebiosciences, San Diego, CA) was diluted 1:100 and incubations were performed at 37°C or overnight, respectively. Detection was carried out on a NEXes instrument (Ventana Medical Systems) using the manufacturer's reagent buffer and detection kits. Upon completion, slides were washed in distilled water, counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated and mounted with permanent media. Appropriate positive and negative controls were included with the study sections. IHC-positive cells were counted manually in 5 representative high-power fields (HPF, 400×), to derive the average number per HPF, by a pathologist blinded to the treatment assignment.

Luminex

To assess the intratumoral immune milieu, cytokines were measured in the tumor supernatant by Luminex 200 (Luminex Corp., Austin, TX). Tumor samples were minced and placed in a 4 mL tube with 1 mL media (10% FBS/RPMI 1640 [Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY]) at a constant tissue weight/mL. After incubation in a 5% CO2 incubator for 24 hours, supernatant was collected by centrifugation (2,000 rpm, 10 min, 4°C), divided in several aliquots and stored in polypropylene tubes at -80°C until analysis. IFN-γ, IFN-α2, IL-1b, regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES), IL-6, IL-10 and IL17) were measured by Luminex assay, performed in duplicate with the appropriate panel of cytokines (Human Cytokine/Chemokine Panel, Premixed 14 Plex, Millipore, Billerica, MA) following manufacturer's instructions.

Lymphocyte phenotyping

Breast cancer tissue from biopsies before and after imiquimod treatment was cultured in 1ml RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS, gentamicin and IL-2 (10ng/mL) in 24-well plates at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator, IL-2 media was replenished every 2 to 3 days. For comparison, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were purified from the blood of the same patient in parallel, drawn on the same day as the biopsy and cultured in the same culture conditions except that they were plated in 96-well-plates at 105 cells/100μL/well. Once TIL cultures were successfully established, cells were collected at various days of culture and subjected to immune phenotyping using multi-parameter flow cytometry. Cells were surface stained with the following antibodies: CD3-PerCP-Cy5.5, CD4-Alexa700 or PE, CD8-Pacific blue, CD25-PE, CD45RO-APC (Biolegend, San Diego, CA), CCR7-FITC (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and CCR6-biotin with Streptavidin-APC (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). For FoxP3 staining, surface staining was followed by intracellular staining using the FoxP3 Staining buffer set (Ebiosciences) and FoxP3-Alexa488 antibody (Biolegend). For intracellular cytokine staining, cells were stimulated for 5 hours at 37°C with PMA 20ng/mL and Ionomycin 500ng/mL (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) and Golgistop (BD Biosciences). Cells were then fixed and permeabilized using the same FoxP3 Staining buffer set (eBioscience) and stained with IFNγ-PeCy7 and IL-4-APC (Ebiosciences). Stained samples were acquired on an LSRII flow cytometer (BD Pharmingen). Flow cytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo software (version 8.8.7, Tree-Star Inc., Ashland, OR).

Statistical analysis

Characteristics of patients are summarized using descriptive statistics including median and ranges for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables. Response rates (CCR+PR) were estimated at the conclusion of the first stage of the trial along with exact 95% confidence intervals. Safety data was summarized by body system and type and most severe Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE version 3.0) grade of individual events at the patient level. Changes in tumor supernatant cytokine values from pre-treatment to post-treatment were evaluated using Wilcoxon non-parametric signed rank tests (2-sided).

RESULTS

Ten women enrolled and completed the first stage of this two stage study. The median age was 50 years. Demographic and tumor characteristics as well as treatment history are shown in Table 1. Seven women presented with a chest wall recurrence, and 3 women presented with skin involvement of a large primary breast cancer in the setting of systemic metastases. All women had failed prior treatment for metastatic/recurrent disease, ranging from 1-3 lines of hormonal therapy (average 2) and 1-5 lines of chemotherapy (average 2.5). Based on the skin area involved, six patients applied 1 packet per day, whereas 4 applied more than 1 packet per day. A second treatment cycle was administered in 2 patients.

Table 1.

Patient demographics, tumor characteristics at baseline and treatment history (n=10)

| Number of patients (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Caucasian Asian Black Other |

6 (60%) 2 (20%) 1 (10%) 1 (10%) |

| Age | Range Median |

44-71 years 50 years |

| Menopausal status | Premenopausal Postmenopausal |

2 (20%) 8 (80%) |

| Pathology | Invasive ductal Invasive lobular |

9 (90%) 1 (10%) |

| HR status | Positive Negative |

8 (80%) 2 (20%) |

| Her2 status at entry | Positive Negative |

6 (60%) 4 (40%) |

| Grade | Poorly differentiated Moderately differentiated |

8 (80%) 2 (20%) |

| Disease presentation | Chest wall recurrence Skin involvement of locally advanced breast cancer with distant metastases |

7 (70%) 3 (30%) |

| Site of metastases | Chest wall/skin only Also extracutaneous metastases: -- Bone/lymph nodes -- Lung/pleura/adrenal |

2(20%) 5 (50%) 3(30%) |

| Prior treatments for recurrent or metastatic disease | Yes -- Chemotherapy +/- anti Her2 (n=7) -- Bevacizumab (n=4) -- Hormonal therapy +/- anti Her2 (n=8) -- Surgery (n=4) -- Radiotherapy (n=5) -- Hyperthermia (n=2) -- Investigational compounds (n=2) |

10 (100%) |

| Concurrent therapy (without prior response) | None Chemotherapy +/- anti Her2 Hormonal +/- anti Her2 |

3 (30%) 2 (20%) 5 (50%) |

HR: hormone receptor, Her2: human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

Patient compliance, defined as the number of administered applications divided by the number of prescribed applications during the entire study period, was excellent with 4 patients not missing any doses, and 6 patients having a compliance score of 95% or greater (1-2 missed doses).

Safety

The treatment was well tolerated, with transient mild to moderate local and systemic adverse events (AEs) consistent with the expected immunomodulatory effects of imiquimod. There were no serious, life-threatening or severe grade AEs and no patient required permanent treatment discontinuation due to AEs. Systemic AEs occurred in 4 of 10 patients (40%), with flu-like symptoms being the most frequent (Table 2). One patient who received 6 packets/day experienced fever, fatigue and depression on treatment, similar to symptoms observed with systemic interferon alpha treatment [14]. The increase of intratumoral as well as circulating IFN-α2 concentrations (from 7 to 19 pg/ml in plasma) with imiquimod treatment in this patient suggests a systemic spillover effect of locally induced cytokines.

Table 2.

Numbers of patients with one or more possibly, probably or definitely related adverse events (only highest grade per patient shown)

| Adverse event | CTCAE v 3.0 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3/4 | |

| Dermatologic (local at tumor site) | |||

| Local pain | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Inflammation/redness | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Infection | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Itching | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Burning | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Desquamation/ulceration with oozing | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Summary of patients with 1 or more dermatologic adverse events | 5 | 2 | 0 |

| Systemic (constitutional, mood, gastrointestinal) | |||

| Depressed mood | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Myalgias | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Arthralgias | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Fever/chills | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Dehydration | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Summary of patients with 1 or more systemic adverse events | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Summary of patients with 1 or more adverse event of any type | 4 | 4 | 0 |

The most frequently observed AEs were local, at the application site, and were experienced by 7 of 10 patients (Table 2). Symptoms included itching, burning and pain at the target site while signs included erythema, desquamation and infection. Topical antibiotics were administered for superficial infection at the treatment site, as indicated. Patient discomfort due to local or systemic AEs, regardless of grade, was successfully managed with temporary dosing interruptions (one patient for 3 weeks) and subsequent reduction of the application frequency from 5x to 3x per week (three patients).

Tumor response

Local tumor response after an 8 week cycle of imiquimod treatment was observed in 2 patients (20%; exact 95% CI 3% - 56%), both of whom achieved a clinical PR at the chest wall (Table 3). Five patients maintained SD, 1 had a NR, and 2 had PD (development of new cutaneous lesions outside of the treatment field during the study). The decision to close the single agent trial, even though the criterion for moving to the second stage was met with a response rate of 20% in stage one, was based on the fact that a new combination trial of imiquimod and local radiotherapy was designed, reflecting promising pre-clinical findings of a combination of imiquimod and local radiotherapy (companion manuscript submitted). The decision to conclude the trial after stage one was supported by the NYUCI Data Safety Monitoring Committee because the achieved response rate of 20% with its 95%CI was reassuring that imiquimod as single agent has efficacy.

Table 3.

Local anti-tumor response. Percentage change in ROI after 8-week imiquimod treatment (n=10).

| Response | ROIchange = (ROIpost-treatment/ROIpre-treatment) × 100% | Patients (%) |

|---|---|---|

| CCR | Absence of any detectable residual disease | none |

| PR | >0 - <50% | 2 (20%) |

| SD | ≥50 - <100% | 5 (50%) |

| NR | ≥100 – <125% | 1 (10%) |

| PD | ≥125% or new skin lesions | 2 (20%) |

ROI: region of interest, CCR: complete clinical response, PR: partial response, SD: stable disease, NR: no response, PD: progressive disease

Interestingly, two of the 10 patients treated in the present study (both with local SD on study) experienced a complete clinical remission upon treatment with a subsequent systemic regimen (fulvestrant). In both women the complete remission in the skin lesion was associated with a systemic complete response (pulmonary and osseous in one patient, mediastinal lymph node and adrenal metastases in the second patient) and have been maintained for over one year (details are being reported separately).

Immune correlates

To monitor the immune response at the tumor site, we examined TILs in paraffin-embedded tissue sections (Figure 1) and in vitro cultures as well as local cytokines in tumor supernatants (Figure 2). Viable tumor punch biopsies were successfully obtained from all patients before and after treatment. The supernatant after 24 hour ex vivo culture was obtained from all samples, and TIL cultures were successfully grown from 7/20 punch biopsy specimens.

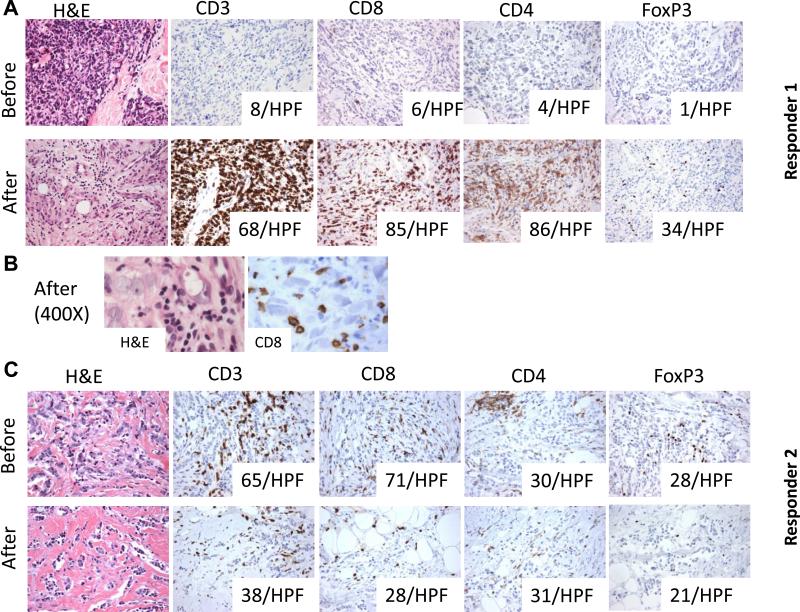

Figure 1. In situ immune changes with imiquimod treatment in the two responders.

A (responder 1): In situ TILs analysis by IHC shows minimal T cell infiltrate before treatment but a marked increase in CD8+ and CD4+ T cells infiltrating the tumor cell nests post-treatment and histological evidence of tumor regression after 8 weeks of topical imiquimod treatment (H&E stain and IHC for CD3, CD4, CD8 and FoxP3, 200×). Numbers in the boxes indicate the number of cells positive for the indicated marker in one HPF (average of 5 HPF, 400×). B: High power microphotographs showing lymphocytes, many positive for CD8, in close contact with cancer cells in the post-treatment biopsy. C (responder 2): In situ TILs analysis by IHC shows a moderate T cell infiltrate before imiquimod treatment. After an 8 week imiquimod treatment course, there is a reduction in CD8+T cells and FoxP3+ T cells while CD4+ T cells remain unchanged (H&E stain and IHC for CD3, CD4, CD8 and FoxP3, 200×). Numbers in the boxes indicate the number of cells positive for the indicated marker in one HPF (average of 5 HPF, 400×).

Figure 2. Changes in the intratumoral cytokine milieu after imiquimod treatment and plasma IL10 levels in all patients.

A: Cytokine analysis of tumor supernatants before and after an 8-week imiquimod cycle is shown for all patients. Supernatants were obtained by 24 hour culture of the tumor samples in medium at a constant tissue mg/ml. Variability among patients is noticeable, as well as a marked increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines in responder 1 (red lines) and decrease of counter-regulatory cytokines in responder 2 (green lines). IFN-γ was only detectable in responder 1 after treatment; levels were below assay detection sensitivity for all other patients. IL-17 was not detectable in pre- and post-treatment supernatants of any patient. B: IL-10 levels in plasma are shown for all patients with detectable levels in only 4 of 10 patients.

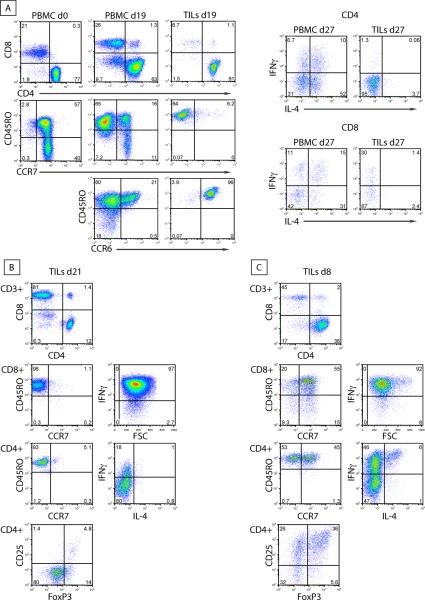

Histological evaluation revealed tumor involvement of skin for all patients before and after imiquimod treatment, with diffuse infiltration extending from the superficial dermis to the subcutis, and variable density of tumor cells occupying from 10 to 80% of the tissue examined. No significant differences were observed in vascularity or degree of apoptotic changes when pre-treatment biopsies were compared to post-treatment ones. Intratumoral T cell infiltrates were present in all specimens at baseline, varying from a sparse infiltrate (<5 CD3+ cells per HPF) to strong infiltration (65 CD3+ cells per HPF). While it was feasible to culture TILs from small tumor punch biopsy specimens, the rate of success in establishing ex vivo TIL cultures was related to lymphocyte density: 7 cultures were established from 14 tumors that had >12 CD3+ cells per HPF, while none could be grown from the 6 tumors with <12 CD3+ cells infiltrating the metastasis. TILs commonly displayed a CCR7-/CD45RO+ effector memory and CCR6+ phenotype compared to PBMC, as shown in an example (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Example of TILs profiles following ex vivo culture (from 3 patients).

A (patient with SD, post-treatment): Breast cancer biopsies and PBMCs (purified from the blood, drawn on the day of the tumor biopsy) were cultured in IL-2 containing media. Cells were collected at the indicated days of culture and subjected to immune phenotyping. FACS plots show the proportions of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in PBMCs and TILs, the different subsets of CD4+ T cells based on the surface expression of CD45RO, CCR7 and CCR6 (left panel) and the intracellular cytokine profile of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (right panel). B (responder 1, post-treatment): Phenotype of TILs. Cells were collected at the indicated days of culture in IL-2 and subjected to immune phenotyping. FACS plots show the percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, their expression of CCR7, CD45RO and FoxP3, as well as their intracellular cytokine profile. C (responder 2, pre-treatment): Phenotype of TILs. Cells were collected at the indicated days of culture in IL-2 and subjected to immune phenotyping. FACS plots show the percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, their expression of CCR7, CD45RO and FoxP3, as well as their intracellular cytokine profile.

Across all patients, quantitative assessment of TILs and pDCs by IHC in tumor sections failed to show a consistent trends pre and post-treatment. In addition, levels of IFN-γ, IFN-α2, IL-1b, RANTES, IL-6 and IL-10, as measured in tumor supernatants after 24 hr ex-vivo culture, did not show a significant change with imiquimod treatment (p>0.05, Figure 2A). Circulating IL-10 was only detectable in 4 of 10 patients (Figure 2B).

The two clinical responders, however, showed in situ changes consistent with an immune-mediated response. In responder 1, the minimal pre-treatment T cell infiltrate changed to a brisk infiltrate post-treatment, comprised of both CD4 and CD8 T cells (Figure 1A). Importantly, there was histological evidence of tumor regression with marked reduction in tumor cell density (from 60% to 15%) and CD8 T cells found in direct contact with tumor cells (Figure 1B). Consistent with the induced TILs infiltrate and the histological appearance of tumor rejection, TILs could be successfully cultured only post-treatment in this patient and were composed of Th1 and cytolytic T cells, of effector memory phenotype, capable of secreting IFN-γ (Figure 3B). IFN-α2 markedly increased in the tumor supernatants post-treatment, and IFN-γ became detectable, albeit at a low level (Figure 2A).

In contrast, responder 2 displayed a substantial T cell infiltrate pre-treatment. TILs evaluated by IHC included CD8+ T cells, and an approximately equal number of CD4+ and FoxP3+ T cells (Figure 1C). TILs were successfully cultured only pre-treatment and included a large percentage of CD4+ T cells co-expressing CD25 and FoxP3, consistent with a regulatory T cell phenotype as well as a subset of IL-4-producting CD4+ T cells (Figure 3C). Post-treatment IHC sections demonstrated a reduction in tumor cell density (from 40 to 20%) accompanied by an overall reduction in T cells. Interestingly, post-treatment tumor supernatants showed decreased concentrations of IL-6 and IL-10, suggesting the reversal of an immune-suppressive milieu (Figure 2A). Overall, these data suggest that the response to imiquimod may be achieved by activation of Th1 and Tc1 T cell responses, and/or by decrease in immunoregulatory cells/cytokines, depending on the pre-existing tumor microenvironment.

DISCUSSION

This is the first report on the efficacy of topical imiquimod in breast cancer skin metastases in patients studied in a prospective trial. Despite the fact that the 10 women accrued were heavily pretreated and had refractory breast cancer skin metastases, the response rate was 20%, with a partial response was achieved in two patients. Imiquimod 5% was applied 5x per week, the dosing frequency used for the treatment of superficial basal cell carcinoma (sBCC) and in a report of two breast cancer patients who experienced a CR at 6 months [9]. Our trial demonstrated feasibility and excellent compliance with self-administration of imiquimod. The safety profile of imiquimod was consistent with the previously published experience in the treatment of sBCC, mainly limited to transient application site reactions and flu-like symptoms.

Immunohistochemical and gene expression analyses suggest that imiquimod-induced regression in primary skin tumors (melanoma, BCC, squamous cell carcinoma) is characterized by significant up-regulation of IFN-α and IFN-γ signaling, enhanced Th1 skewing and CD8 T cell homing to the tumor, reversal of T regulatory cell (Treg) function and modulation of the vasculature facilitating cellular infiltration, although the direct induction of apoptosis in superficial tumors as well as mDC and pDC mediated toxicity have also been described [7, 15-20]. Until now, data from cutaneous metastases treated in prospective studies with topical imiquimod alone were lacking. In the current study, pre-existing lymphocytic infiltrates within the cutaneous metastases were highly variable and ranged from sparse to diffuse. Biopsies after an 8 week treatment course of imiquimod showed lack of consistent quantitative changes of the infiltrate. Furthermore, no increases in pDCs were seen post-treatment (not shown). These observations are in contrast to both our prior study showing that percutaneous stimulation of TLR7 via imiquimod in healthy skin (without immune cell infiltrates pre-treatment) attracts pDCs and induces an inflammatory infiltrate mainly composed of T cells [21], and to the results of a recent study of preoperative imiquimod treatment of primary malignant melanoma demonstrating an increase in T cell infiltrates [15]. Effects of imiquimod may depend on the pre-existing tumor microenvironment, although the timing of biopsy in our trial compared to the other two studies (after 8 weeks versus 1-2 weeks of imiquimod application) might also have contributed to the difference.

The biopsied metastases of the two responders displayed post-treatment changes highly suggestive of a local anti-tumor immune response induced by imiquimod, even though the tumors greatly differed in the extent of the pre-existing lymphocytic infiltrate and local cytokine milieu as well as in their response to treatment with imiquimod. In responder 1 without a pre-existing lymphocytic infiltrate, imiquimod treatment was associated with development of a Th1-polarized immune response. In responder 2 with a baseline lymphocytic infiltrate including a substantial percentage of Treg and evidence of Th2 polarization, imiquimod response was associated with a reduction in immunosuppression. The extent of chest wall involvement and bone and lymph node metastases was similar in the two patients, only tumor histology was different: responder 1 had an infiltrating ductal carcinoma (IDC) while responder 2 had an infiltrating lobular carcinoma (ILC, Supplementary Table 1). This difference may have contributed to the disparate response, as we have previously observed differences between IDC and ILC in their interaction with the local immune system [22]. Overall, the variability of TILs infiltrate (Supplemental Figure 1) and local cytokine milieu among all patients after and even before treatment points to the complexity of the interactions between tumor and host immune system in the setting of skin metastases. Genetic features of the patient may contribute to the differential response. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms have been described for TLR7 including alleles that are associated with treatment outcomes for viral infections [23]. Likewise, a TLR4 loss-of-function allele has been shown to impact outcome of breast cancer patients post-treatment [24], suggesting that genetic variation might account for the diverse response to TLR agonists.

Limitations of this study are the small number of patients which precludes the identification of significant differences between responders and non-responders, the single arm design without a comparator group as well as the option for patients to continue on a systemic regimen concurrently (if no prior response in skin), which may have affected the immunological response.

As mentioned two patients who had SD on imiquimod and were subsequently switched to fulvestrant, an estrogen receptor antagonist, had a complete clinical response to that regimen. Since CRs were rarely seen in a phase III trial of fulvestrant (only 4 of 362 women) [25], it is reasonable to hypothesize that immune effects of imiquimod may have contributed to their outcome. Unexpectedly higher response rates to chemotherapy have been reported in several solid tumors, when chemotherapy was preceded by cancer vaccination [26-30]. Recent evidence that anti-tumor immunity contributes to the response to chemotherapy [24] raise the possibility that immunotherapy may condition the host immune system to achieve an anti-tumor effect synergistic with at least some cytocidal treatments.

Activation of TLRs not only induces inflammatory cytokines but can also trigger negative regulatory circuits, for example by promoting the secretion of IL-10 [31, 32], as recently demonstrated in the neu-transgenic mouse model of breast cancer in which IL-10 upregulation was shown to limit imiquimod's therapeutic effect [33]. In our series, local levels of IL-10, as measured in tumor supernatants, did not show a significant change with imiquimod treatment, although a decrease was seen in two patients including responder 2 (Figure 2A). Circulating IL-10 was detectable in 4 of 10 patients, but there was no trend to increase with imiquimod treatment (Figure 2B).

In summary, we have shown that topical imiquimod can be a useful treatment modality for breast cancer metastatic to skin or chest wall. Importantly, data indicate that imiquimod is able to promote a pro-immunogenic tumor microenvironment in metastatic breast cancer. To improve the efficacy of topical imiquimod, we have studied a combinatorial approach with local radiotherapy in the TSA murine model of breast cancer with cutaneous involvement. Radiotherapy is a frequently used treatment modality for chest wall recurrences and has been shown to synergize with immunotherapies [34, 35]. In this preclinical model, the combination with topical imiquimod and local RT showed synergistic anti-tumor efficacy, with complete regressions, prolonged survival and improved systemic tumor control. A combination clinical trial is ongoing (clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT01421017).

Supplementary Material

TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE.

Skin metastases of solid tumors remain a therapeutic challenge. After melanoma, breast cancer is the most common tumor to metastasize to the skin. The toll-like receptor 7 agonist imiquimod, a FDA-approved imidazoquinoline is highly effective in inducing immune-mediated rejection of primary skin malignancies when topically applied. Here we show in a prospective trial of refractory breast cancer that topical imiquimod can also stimulate local anti-tumor immunity within treated metastases and induce their regression. As treatment is easy to apply, well tolerated and can promote a pro-immunogenic tumor microenvironment in metastases, imiquimod can be easily combined with other treatment modalities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all participating patients and research teams at the New York University and Bellevue Cancer Centers.

FUNDING

The work was supported by the National Cancer Institute: 5P30 CA16087-31 (NYUCI Center Support Grant), K23CA125205P50 (S.A.), NIH 5PCA016087-29 (Translational Pilot grant, S.A.), NIH R01 CA113851 (S.D.) and in part by a grant from the CTSI grant-NCRR-NIH 1UL1RR029893 and The Chemotherapy Foundation (S.D.).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: Tze-Chiang Meng is a consultant for, and was previously an employee of, Graceway Pharmaceuticals, the manufacturer of imiquimod 5% cream.

REFERENCES

- 1.Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis: a meta-analysis of data. South Med J. 2003;96:164–167. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000053676.73249.E5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228–236. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70173-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hemmi H, Kaisho T, Takeuchi O, Sato S, Sanjo H, Hoshino K, et al. Small anti-viral compounds activate immune cells via the TLR7 MyD88-dependent signaling pathway. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:196–200. doi: 10.1038/ni758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takeda K, Akira S. TLR signaling pathways. Semin Immunol. 2004;16:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheever MA. Twelve immunotherapy drugs that could cure cancers. Immunol Rev. 2008;222:357–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams S. Toll-like receptor agonists in cancer therapy. Immunotherapy. 2009;1:949–964. doi: 10.2217/imt.09.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panelli MC, Stashower ME, Slade HB, Smith K, Norwood C, Abati A, et al. Sequential gene profiling of basal cell carcinomas treated with imiquimod in a placebo-controlled study defines the requirements for tissue rejection. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R8. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-1-r8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schon MP, Schon M. TLR7 and TLR8 as targets in cancer therapy. Oncogene. 2008;27:190–199. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hengge UR, Roth S, Tannapfel A. Topical imiquimod to treat recurrent breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;94:93–94. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-7017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heber G, Helbig D, Ponitzsch I, Wetzig T, Harth W, Simon JC. Complete remission of cutaneous and subcutaneous melanoma metastases of the scalp with imiquimod therapy. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7:534–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2009.07038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harrison LI, Skinner SL, Marbury TC, Owens ML, Kurup S, McKane S, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of imiquimod 5% cream in the treatment of actinic keratoses of the face, scalp, or hands and arms. Arch Dermatol Res. 2004;296:6–11. doi: 10.1007/s00403-004-0465-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Del Rosso JQ, Sofen H, Leshin B, Meng T, Kulp J, Levy S. Safety and Efficacy of Multiple 16-week Courses of Topical Imiquimod for the Treatment of Large Areas of Skin Involved with Actinic Keratoses. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:20–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kouloulias VE, Dardoufas CE, Kouvaris JR, Gennatas CS, Polyzos AK, Gogas HJ, et al. Liposomal doxorubicin in conjunction with reirradiation and local hyperthermia treatment in recurrent breast cancer: a phase I/II trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:374–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirkwood JM, Bender C, Agarwala S, Tarhini A, Shipe-Spotloe J, Smelko B, et al. Mechanisms and management of toxicities associated with high-dose interferon alfa-2b therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3703–3718. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Narayan R, Nguyen H, Bentow JJ, Moy L, Lee DK, Greger S, et al. Immunomodulation by Imiquimod in Patients with High-Risk Primary Melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2011 doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wenzel J, Uerlich M, Haller O, Bieber T, Tueting T. Enhanced type I interferon signaling and recruitment of chemokine receptor CXCR3-expressing lymphocytes into the skin following treatment with the TLR7-agonist imiquimod. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:257–262. doi: 10.1111/j.0303-6987.2005.00297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark RA, Huang SJ, Murphy GF, Mollet IG, Hijnen D, Muthukuru M, et al. Human squamous cell carcinomas evade the immune response by down-regulation of vascular E-selectin and recruitment of regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2221–2234. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schon M, Bong AB, Drewniok C, Herz J, Geilen CC, Reifenberger J, et al. Tumor-selective induction of apoptosis and the small-molecule immune response modifier imiquimod. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1138–1149. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drobits B, Holcmann M, Amberg N, Swiecki M, Grundtner R, Hammer M, et al. Imiquimod clears tumors in mice independent of adaptive immunity by converting pDCs into tumor-killing effector cells. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:575–585. doi: 10.1172/JCI61034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stary G, Bangert C, Tauber M, Strohal R, Kopp T, Stingl G. Tumoricidal activity of TLR7/8-activated inflammatory dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1441–1451. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adams S, O'Neill DW, Nonaka D, Hardin E, Chiriboga L, Siu K, et al. Immunization of malignant melanoma patients with full-length NY-ESO-1 protein using TLR7 agonist imiquimod as vaccine adjuvant. J Immunol. 2008;181:776–784. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta R, Babb JS, Singh B, Chiriboga L, Liebes L, Adams S, et al. The numbers of FoxP3+ lymphocytes in sentinel lymph nodes of breast cancer patients correlate with primary tumor size but not nodal status. Cancer Invest. 2011;29:419–425. doi: 10.3109/07357907.2011.585193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schott E, Witt H, Neumann K, Bergk A, Halangk J, Weich V, et al. Association of TLR7 single nucleotide polymorphisms with chronic HCV-infection and response to interferona-based therapy. J Viral Hepat. 2008;15:71–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Tesniere A, Obeid M, Ortiz C, Criollo A, et al. Toll-like receptor 4-dependent contribution of the immune system to anticancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Nat Med. 2007;13:1050–1059. doi: 10.1038/nm1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Di Leo A, Jerusalem G, Petruzelka L, Torres R, Bondarenko IN, Khasanov R, et al. Results of the CONFIRM phase III trial comparing fulvestrant 250 mg with fulvestrant 500 mg in postmenopausal women with estrogen receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4594–4600. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.8415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiappori AA, Soliman H, Janssen WE, Antonia SJ, Gabrilovich DI. INGN-225: a dendritic cell-based p53 vaccine (Ad.p53-DC) in small cell lung cancer: observed association between immune response and enhanced chemotherapy effect. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2010;10:983–991. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2010.484801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wheeler CJ, Das A, Liu G, Yu JS, Black KL. Clinical responsiveness of glioblastoma multiforme to chemotherapy after vaccination. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5316–5326. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gribben JG, Ryan DP, Boyajian R, Urban RG, Hedley ML, Beach K, et al. Unexpected association between induction of immunity to the universal tumor antigen CYP1B1 and response to next therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4430–4436. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radfar S, Wang Y, Khong HT. Activated CD4+ T cells dramatically enhance chemotherapeutic tumor responses in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2009;183:6800–6807. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arlen PM, Gulley JL, Parker C, Skarupa L, Pazdur M, Panicali D, et al. A randomized phase II study of concurrent docetaxel plus vaccine versus vaccine alone in metastatic androgen-independent prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1260–1269. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saraiva M, O'Garra A. The regulation of IL-10 production by immune cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:170–181. doi: 10.1038/nri2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bogunovic D, Manches O, Godefroy E, Yewdall A, Gallois A, Salazar AM, et al. TLR4 engagement during TLR3-induced proinflammatory signaling in dendritic cells promotes IL-10-mediated suppression of antitumor immunity. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5467–5476. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu H, Wagner WM, Gad E, Yang Y, Duan H, Amon LM, et al. Treatment failure of a TLR-7 agonist occurs due to self-regulation of acute inflammation and can be overcome by IL-10 blockade. J Immunol. 2010;184:5360–5367. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Demaria S, Kawashima N, Yang AM, Devitt ML, Babb JS, Allison JP, et al. Immune-mediated inhibition of metastases after treatment with local radiation and CTLA-4 blockade in a mouse model of breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:728–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Formenti SC, Demaria S. Systemic effects of local radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:718–726. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70082-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.