Abstract

Cognitive impairment has a major impact on the lives of people with multiple sclerosis (MS). Yet it is often underdiagnosed, and more-effective assessment methods are needed. In particular, brief measures that focus on cognitive functioning in daily life situations, are sensitive to modest change over time, and do not require a highly skilled assessor merit exploration. The purpose of this exploratory study was to investigate the performance of individuals with MS on three relatively new measures—the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Cognitive Concerns and Abilities Scales and the Everyday Problems Test (EPT)—and to compare scores on these measures with scores on neurocognitive performance measures typically used to assess cognitive functioning in people with MS. Twenty-nine individuals with MS who reported cognitive concerns participated in the study. Most were non-Hispanic white women with relapsing-remitting MS that was diagnosed approximately 18 years previously. All three measures yielded reliability coefficients of 0.80 or above and also demonstrated sensitivity to change following an educational intervention. Scores on the Revised EPT (EPT-R) were moderately correlated with scores on five standard neuropsychological measures. Compared with scores on the PROMIS Cognitive Concerns Scale, those on the self-reported PROMIS Cognitive Abilities Scale tended to correlate more highly with the neurocognitive performance measures, although the correlations were generally small. While results of this exploratory study are promising, future research should be conducted with larger and more diverse samples of people with MS to determine the broader utility of these measures.

Impairments in cognitive abilities are among the most disturbing side effects of multiple sclerosis (MS). Benedict et al.1 estimated that approximately half of people diagnosed with MS have cognitive deficits, particularly in the areas of processing speed and episodic memory. These deficits affect all areas of life and frequently preclude employment.2–4 Because cognitive impairment may occur early in the course of MS,5 timely assessment of cognitive functioning in clinical settings is critical. As Benedict and colleagues6 pointed out, however, cognitive impairment in people with MS has been underdiagnosed, and more-effective assessment methods are needed.

Multiple measures, including both self-report and performance-based tests, have been used to assess cognitive functioning in people with MS. One of the most widely accepted neuropsychological assessment batteries is the Minimal Assessment of Cognitive Function in Multiple Sclerosis (MACFIMS).1 The MACFIMS battery7 is based on recommendations from an international MS consensus conference. It consists of seven well-established neuropsychological tests covering five cognitive domains (language, spatial processing, new learning and memory, processing speed and working memory, and executive function). Although there is strong evidence to support the reliability and validity of the MACFIMS,7 the battery is costly, because the tests must be administered by highly trained testers and take approximately 2 hours to complete. Moreover, the MACFIMS assesses functioning in a highly controlled testing situation and may be less useful in reflecting day-to-day cognitive functioning outside the standardized testing environment: “There is the question of the extent to which the laboratory ability and processing tasks traditionally studied by psychologists represent the mechanics underlying the pragmatic tasks of daily living.”8(p69) It is also not clear that the neuropsychological tests used to diagnose impairment are sensitive to the change that might result from psychoeducational interventions designed to build cognitive skills to improve the daily lives of people with MS. Consequently, performance measures that focus on cognitive functioning in daily life situations, are sensitive to modest change over time, and do not require a highly skilled assessor or specialized equipment merit investigation. One such measure is the Everyday Problems Test (EPT),9 which was developed to test cognitive abilities in daily living situations among older adults.

In addition to performance measures that can be easily administered and reflect everyday activities, brief and psychometrically sound self-report measures of perceived cognitive functioning are needed to complement performance tests. Such measures are particularly useful for rapid screening in clinical settings. Although a number of self-report measures exist and have been used with individuals with MS (eg, Multiple Sclerosis Neuropsychological Screening Questionnaire [MSNQ],6 Perceived Deficits Questionnaire10), more recent measures have capitalized on contemporary advances in psychometric theory to produce relatively short instruments that discriminate well throughout the underlying cognitive abilities continuum. Two such “new generation” self-report measures are the Cognitive Concerns and Cognitive Abilities Scales derived from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS).11 Therefore, the purpose of this exploratory study was to investigate the performance of individuals with MS on the PROMIS Scales and the EPT, and to compare scores on these measures with scores on neuropsychological performance tests typically used to assess cognitive functioning in people with MS.

Methods

Recruitment

Following institutional review board approval of the study, participants were recruited from among those who had recently participated in a cognitive rehabilitation intervention study and had agreed to participate in future studies. They had been enlisted via notices on the research page of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society website and contacts with local neurologists.12 To be eligible for the study, participants had to have physician confirmation of their MS diagnosis and had to have been diagnosed at least 6 months previously. In addition, participants had to score at least 20 on the Perceived Deficits Questionnaire,10 which was administered in a telephone screening.

Test Procedure

All procedures were approved by the university institutional review board. Measures were administered in a university research setting. The tests were administered according to the standardized protocols provided by the instrument developers. The tester was trained to administer the neuropsychological tests by an experienced neuropsychologist and his licensed psychological associate. The instrument battery took 90 minutes on average to administer.

Instruments

Developed in a longitudinal study of older adults, the 42-item EPT assesses the cognitive ability to reason and solve problems encountered in daily living.9 Performance is assessed in seven areas: Meal Preparation/Nutrition, Medications, Phone Use, Shopping, Financial Management, Transportation, and Household Management. The person being tested is presented with directions, charts, or forms, and asked written questions about how to use them. Separate norms are provided for men and women in different age and education levels. Internal consistency reliability coefficients exceeding 0.80 and a test/retest correlation of 0.83 have been reported in samples of older adults. Construct validity was established by comparing scores to actual performance of household tasks (0.67), and convergent validity was established by comparing EPT performance with performance on other self-report measures of functioning. Significant performance differences were found between elders diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease and those who were not.

The Cognitive Concerns and Cognitive Abilities Scales were derived from the PROMIS. An initiative of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), PROMIS is intended to capitalize on recent advances in measurement theory to develop a dynamic and valid patient-reported outcomes system (http://www.nihpromis.org). PROMIS, based on the World Health Organization framework of physical, mental, and social health, consists of a large item bank that provides researchers with a common item repository that can be administered in print or as computerized adaptive tests. Nearly 7000 items available from patient-reported outcome measures in areas such as pain, emotional distress, and physical functioning were reviewed. The items were subjected to quantitative analysis using Item Response Theory and qualitative analysis using cognitive interviewing procedures.11 A key feature of PROMIS has been the addressing of accessibility for people with disabilities in its development. The PROMIS Cognitive Abilities Scale consists of eight items, such as “My thinking has been as fast as usual.” The PROMIS Cognitive Concerns Scale is also an eight-item scale, with items such as “I have had to work harder than usual to keep track of what I was doing.” Items on both scales utilize 5-point rating scales from “not at all” to “very much.” Items are summed to create a total score.

Scores on the EPT, Cognitive Concerns, and Cognitive Abilities measures were compared with scores on the following five tests from the MACFIMS battery. These tests have been used extensively to diagnose cognitive impairment in people with MS:

Controlled Oral Word Association Test. The Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT) assesses verbal fluency and word finding.13 The numbers of correct words on three 1-minute word-naming trials are combined to yield a total score.

California Verbal Learning Test. The California Verbal Learning Test, second edition (CVLT-II), assesses verbal memory.14 Examiners read 16 words and ask participants to repeat as many words as possible. After a 25-minute interval, participants are asked to recall the information again without further exposure. Scores on this measure include total recall across the five trials and delayed recall.

Brief Visuospatial Memory Test–Revised. The Brief Visuospatial Memory Test–Revised (BVMT-R) tests nonverbal learning and memory.15 Participants are asked to reproduce a page with six figures they are shown for 10 seconds on three separate trials. Designs are scored based on accuracy and location scoring criteria. The three free-recall trials are summed and followed by a 25-minute delayed recall trial.

Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test. The Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test (PASAT) assesses auditory information processing speed and flexibility as well as calculation abilities.16 One of the most commonly used and most sensitive measures of cognitive function in MS, the PASAT includes 60 trials presented at inter-stimulus intervals of 3 and 2 seconds, as recommended by Rao et al.17 The total numbers of correct responses for 3- and 2-minute intervals are reported separately.

Symbol Digit Modalities Test. The Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) assesses complex scanning and visual tracking.18 Participants are presented with a series of symbols and digits and instructed to then verbalize the digit associated with each symbol. The number of correct responses in 90 seconds constitutes the score.

Results

After data entry was double-checked, data analyses were conducted using SPSS, version 19 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics and correlations were then computed.

Sample Description

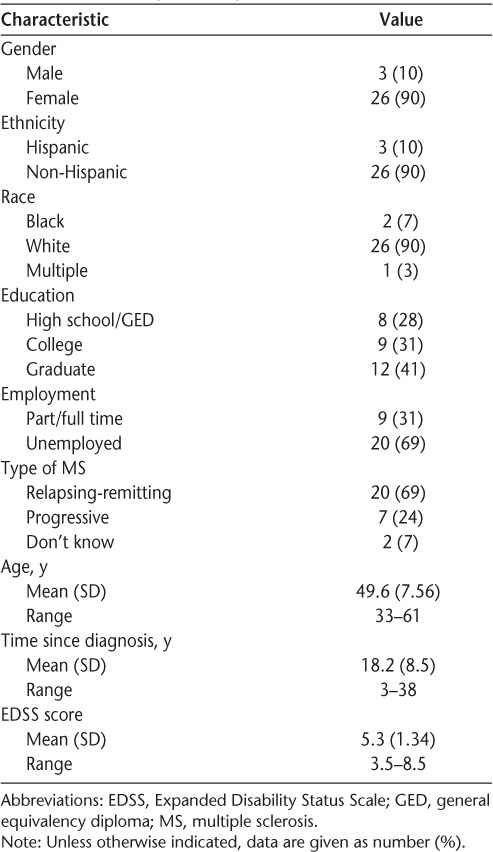

Twenty-nine individuals participated in this exploratory study. The sample was 90% female, and 83% indicated that they were nonminority white (Table 1). They had been diagnosed an average of 18 years previously. The average age was 50 years. Seventy-two percent had at least a college education. Thirty-one percent were working, but 48% reported being unemployed due to their disabilities. Sixty-nine percent indicated that they had relapsing-remitting MS. The average score on the Self-Administered Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS)19 was 5.3.

Table 1.

Study sample background characteristics (N = 29)

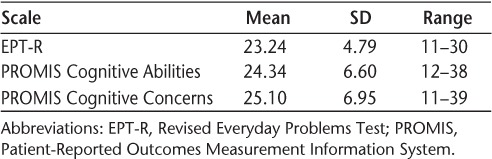

Characteristics of EPT, Cognitive Concerns, and Cognitive Abilities Scores

Means, standard deviations, and ranges for the EPT and the PROMIS Cognitive Concerns and Cognitive Abilities Scales are shown in Table 2. Scores were approximately normally distributed. Cronbach α coefficients for the PROMIS Cognitive Concerns and PRO-MIS Cognitive Abilities were each 0.94. Two-month test/retest correlations with a subset of the sample were 0.80 for Cognitive Abilities and 0.83 for Cognitive Concerns (n = 14). The correlation between Cognitive Concerns and Cognitive Abilities was −0.80.

Table 2.

Baseline descriptive statistics for the EPT-R and the PROMIS Cognitive Abilities and PROMIS Cognitive Concerns Scales (N = 29)

Initial internal consistency reliability analysis for the EPT revealed that several EPT item/total correlations were low or could not be computed because some items were answered correctly by all or nearly all respondents. Consequently, permission was granted by the instrument developer to create a shortened form of the EPT that eliminated 12 of the items (SL Willis, written communication, December 2011). The reliability coefficient for the revised 30-item version was 0.83 and the 2-month test/retest reliability was 0.86 for the 14 individuals tested a second time. The correlation between total scores on the original EPT and the Revised EPT was r = 0.99. The analyses presented here utilize the revised version of the EPT (the EPT-R).

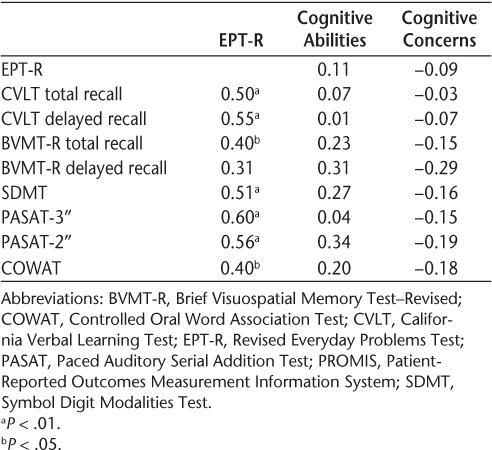

As shown in Table 3, scores on the EPT-R had moderately strong positive correlations with those of all the neuropsychological tests. The strongest correlations were between the EPT-R and the 3-second PASAT (r = 0.60) and 2-second PASAT (r = 0.56). The only correlation that did not reach the .05 level of statistical significance was between the EPT-R and the BVMT-R delayed recall (r = 0.31, P = .10). In contrast, EPT-R scores were not correlated with the self-report measures.

Table 3.

Correlations among EPT-R, PROMIS Cognitive Abilities, PROMIS Cognitive Concerns, and other cognitive tests (N = 29)

An interesting pattern emerges with respect to the PROMIS Scales. Scores on the PROMIS Cognitive Abilities Scale were somewhat more highly correlated than PROMIS Cognitive Concerns Scale scores with neuropsychological test performance, particularly the BVMT-R, the SDMT, and the 2-second PASAT.

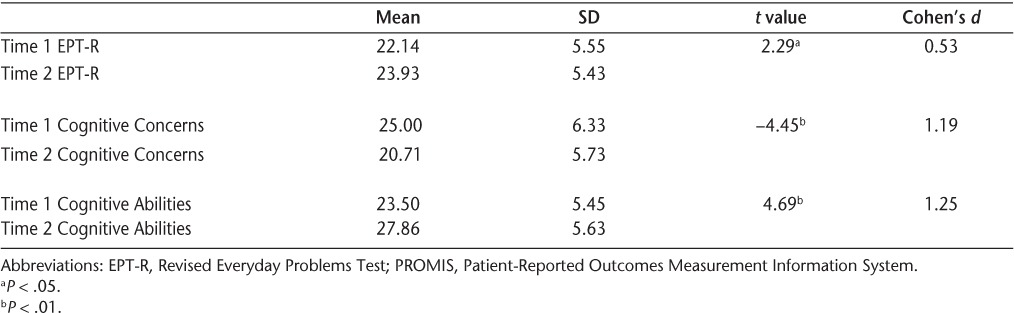

Sensitivity to Change

A subset of this sample (n = 14) was retested after using a computer program designed to build cognitive skills for 8 weeks. Paired t-test analyses revealed statistically significant change from pretest to posttest on the EPT-R and both PROMIS Scales (Table 4). The corresponding effect sizes were moderate to large (Cohen's d value of 0.53 for the EPT, 1.19 for PROMIS Cognitive Concerns, and 1.25 for PROMIS Cognitive Abilities). These changes should be interpreted cautiously, however, because of the small sample size.

Table 4.

Change in EPT-R, PROMIS Cognitive Concerns, and PROMIS Cognitive Abilities scores following computer practice (n = 14)

Discussion

Although previous research has examined the cognitive performance of people with MS using neuropsychological batteries such as the MACFIMS and self-report measures, such as the Multiple Sclerosis Neuropsychological Screening Questionnaire (MSNQ), to our knowledge, performance on the PROMIS and EPT among people with MS has not previously been reported. All three measures demonstrated acceptable psychometric properties in this sample of community-dwelling individuals with MS.

The results suggest that the EPT-R may complement the standard neuropsychological tests by assessing cognitive functioning in everyday activities in a simple-to-administer format. Although standard neuropsychological testing may still be needed to diagnose cognitive impairment, tools such as the EPT may prove to be useful adjuncts for assessing cognitive performance in day-to-day settings. The revised 30-item version of the EPT yielded reliability coefficients above 0.80 and was also moderately correlated with standard neuropsychological tests. The EPT-R takes less time to administer than a standard neuropsychological battery, thereby reducing the potential for patient fatigue. Other tests have been developed to evaluate individuals' ability to carry out basic day-to-day functional activities, such as the Direct Assessment of Functional Status or the Rivermead Behavioral Memory Test, but many require specialized equipment and trained administrators. The fact that the EPT-R is a paper-and-pencil test that can be administered with little formal training makes it feasible to administer in many settings where a more formal assessment is not needed.

Our ability to shorten the EPT by approximately 30% while retaining acceptable reliability and validity increases its feasibility as a clinical data-collection tool for MS patients. The original 42-item EPT took approximately half an hour on average to complete. Reducing its length by 30% may markedly shorten the administration, thereby lessening patient fatigue and burden.

The PROMIS Cognitive Abilities and Cognitive Concerns self-report measures also show “promise” as short, easy-to-administer measures of self-reported cognitive functioning. Their scores were correlated in the expected direction with the neurocognitive tests and show initial evidence of sensitivity to change following a computer intervention designed to build cognitive skills. The eight-item Cognitive Concerns and Cognitive Abilities measures demonstrate good reliability, reflecting the careful item calibration process underlying PRO-MIS. These scales provide researchers and clinicians alike with brief measures of self-reported cognitive function that minimize the data-collection burden on people with MS. Because they are part of the NIH PROMIS, using these scales enables comparisons with research investigating outcomes for patients with a variety of chronic conditions.

Although the results must be interpreted cautiously because of the small sample size, they do suggest that the EPT-R and the PROMIS Cognitive Abilities and Cognitive Concerns Scales may be sensitive to change following a cognitive intervention. This finding has great significance for researchers who require cognitive measures that can detect meaningful improvement in cognitive functioning following an intervention.

Future investigations of these measures should be conducted with larger and more diverse samples of people with MS. This sample was recruited from individuals in one community, not a clinic population. Sixty-nine percent of participants reported that they had relapsing-remitting MS, and participants had been diagnosed an average of 18 years previously. Although everyone in this study self-reported at least some level of cognitive impairment, this volunteer sample of community-dwelling individuals may not be representative of people seeking medical treatment for cognitive impairment. It will also be important to examine the performance of these measures in a sample of individuals with more progressive forms of MS and those who are more recently diagnosed. Future studies might also incorporate additional exclusion criteria that could affect cognitive functioning, such as certain medications, psychiatric diagnoses, substance use, or other comorbid neurologic, medical, or orthopedic conditions. Moreover, future studies should investigate the sensitivity of the EPT-R and the Cognitive Abilities and Cognitive Concerns PROMIS measures to meaningful change in cognitive functioning following various interventions.

PracticePoints.

More-effective assessment methods are needed to evaluate cognitive impairment in people with MS.

The Revised Everyday Problems Test (EPT-R) and the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Cognitive Scales are psychometrically sound measures that are brief and feasible for administration in clinical settings.

The EPT-R and PROMIS Cognitive Scales demonstrate sensitivity to change following interventions designed to build cognitive skills in people with MS.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of HwaYoung Lee, Lynn Chen, Ana Todd, Marian Morris, Lauren Culp, Sherry Morgan, and Vicki Kullberg with data collection, data entry, and analysis.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research grant 1R21NR011076. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Nursing Research or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Benedict RH, Cookfair D, Gavett R et al. Validity of the Minimal Assessment of Cognitive Function in Multiple Sclerosis (MACFIMS) J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2006;12:549–558. doi: 10.1017/s1355617706060723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rao SM, Leo GJ, Ellington L, Nauertz T, Bernardin L, Unverzagt F. Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. II. Impact on employment and social functioning. Neurology. 1991;41:692–696. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.5.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amato MP, Ponziani G, Rossi F, Liedl CL, Stefanile C, Rossi L. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis: the impact of depression, fatigue and disability. Mult Scler. 2001;7:340–344. doi: 10.1177/135245850100700511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shevil E, Finlayson M. Perceptions of persons with multiple sclerosis on cognitive changes and their impact on daily life. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28:779–788. doi: 10.1080/09638280500387013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulz D, Kopp B, Kunkel A, Faiss JH. Cognition in the early stage of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2006;253:1002–1010. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benedict RH, Munschauer F, Linn R et al. Screening for multiple sclerosis cognitive impairment using a self-administered 15-item questionnaire. Mult Scler. 2003;9:95–101. doi: 10.1191/1352458503ms861oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benedict RH, Fischer JS, Archibald CJ et al. Minimal neuropsychological assessment of MS patients: a consensus approach. Clin Neuropsychol. 2002;16:381–397. doi: 10.1076/clin.16.3.381.13859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willis SL, Jay GM, Diehl M, Marsiske M. Longitudinal change and prediction of everyday task competence in the elderly. Res Aging. 1992;14:68–91. doi: 10.1177/0164027592141004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willis SL. Manual for the Everyday Problems Test. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sullivan JIL, Edgley K, DeHoux E. A survey of multiple sclerosis, part 1: perceived cognitive problems and compensatory strategy use. Can J Rehabil. 1990;4:99–105. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress on an NIH-Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care. 2007;45:S3–11. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stuifbergen AK, Becker H, Perez F, Morrison J, Kullberg V, Todd A. A randomized controlled trial of a cognitive rehabilitation intervention for persons with multiple sclerosis. Clin Rehabil. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Benton AL, Sivan AB, Hamsher KD, Varney NR, Spreen O. Contributions to Neuropsychological Assessment. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delis DC, Kaplan E, Kramer JH. California Verbal Learning Test Manual–Adult Version. 2nd ed. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benedict RH. Brief Visuospatial Memory Test–Revised: Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gronwall DM. Paced auditory serial-addition task: a measure of recovery from concussion. Percept Mot Skills. 1977;44:367–373. doi: 10.2466/pms.1977.44.2.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao SM, Leo GJ, Bernardin L, Unverzagt F. Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. I. Frequency, patterns, and prediction. Neurology. 1991;41:685–691. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.5.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith A. Symbol Digit Modalities Test Manual. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowen J, Gibbons L, Gianas A, Kraft GH. Self-administered Expanded Disability Status Scale with functional system scores correlates well with a physician-administered test. Mult Scler. 2001;7:201–206. doi: 10.1177/135245850100700311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]