Summary

Gene regulation by cytokine-activated transcription factors of the signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) family requires serine phosphorylation within the transactivation domain (TAD). STAT1 and STAT3 TAD phosphorylation occurs upon promoter binding by an unknown kinase. Here, we show that the cyclin-dependent kinase 8 (CDK8) module of the Mediator complex phosphorylated regulatory sites within the TADs of STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5, including S727 within the STAT1 TAD in the interferon (IFN) signaling pathway. We also observed a CDK8 requirement for IFN-γ-inducible antiviral responses. Microarray analyses revealed that CDK8-mediated STAT1 phosphorylation positively or negatively regulated over 40% of IFN-γ-responsive genes, and RNA polymerase II occupancy correlated with gene expression changes. This divergent regulation occurred despite similar CDK8 occupancy at both S727 phosphorylation-dependent and -independent genes. These data identify CDK8 as a key regulator of STAT1 and antiviral responses and suggest a general role for CDK8 in STAT-mediated transcription. As such, CDK8 represents a promising target for therapeutic manipulation of cytokine responses.

Highlights

► CDK8 phosphorylates STAT transactivation domains in cytokine responses ► The findings implicate CDK8 as a broad regulator of STATs and cytokine responses ► CDK8 selectively regulates IFN-γ target-gene expression ► The CDK8 module is required for IFN-inducible antiviral responses

Introduction

The immune system is controlled by cytokine-mediated communication that is dependent on the Janus kinase (JAK)- signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) signaling pathway and downstream changes in gene expression (Levy and Darnell, 2002). Failures in cytokine responses can result in disorders including immunodeficiency, autoimmunity, or hematopoietic cancer. The transcription factors of the STAT family translate cytokine signals into changes in gene expression patterns. Upon phosphorylation of a tyrosine (around residue 700) by cytokine-receptor-associated JAKs, STAT homodimers or heterodimers translocate to the nucleus, bind DNA, and regulate transcription. STATs can be posttranslationally modified on residues other than tyrosine, and the best characterized is phosphorylation of serine in the C-terminal transactivation domain (TAD), originally described for S727 of STAT1 and STAT3 by the Darnell laboratory (Wen et al., 1995).

TAD phosphorylation fulfills several independent functions that are still incompletely understood. TAD phosphorylation has been most intensively studied in the canonical JAK-STAT pathway, referred to as the cytokine-elicited signaling cascade, causing STAT phosphorylation on both tyrosine and serine (Decker and Kovarik, 2000; Li, 2008). Noncanonical TAD serine phosphorylation of STATs occurs without concomitant tyrosine phosphorylation. Most studies, including those of gene-targeted animals, propose that canonical TAD serine phosphorylation increases transcriptional activity of STAT1, STAT3, STAT4, and STAT5 (Friedbichler et al., 2010; Kovarik et al., 2001; Morinobu et al., 2002; Shen et al., 2004; Varinou et al., 2003; Wen et al., 1995).

The identity of the kinases responsible for canonical serine phosphorylation has so far not been sufficiently clarified. We recently reported that IFN-induced TAD phosphorylation on S727 of STAT1 occurs only on promoter-bound STAT1 (Sadzak et al., 2008). Similar results were subsequently reported for IL-6-induced S727 phosphorylation of STAT3 (Yang et al., 2010). This chromatin-associated signaling suggests that cytokine-induced TAD serine phosphorylation is accomplished by components of the general transcription machinery, assembled at the promoter.

The human Mediator complex acts as a general transcription factor that is broadly required for the regulation of RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) activity and RNAPII-dependent transcription (Meyer et al., 2010; Taatjes, 2010; Takahashi et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2005). A four-subunit CDK8 module, consisting of cyclin-dependent kinase 8 (CDK8), cyclin C (CynC), MED12, and MED13, reversibly associates with Mediator and regulates transcription initiation and reinitiation by controlling RNAPII-Mediator interactions (Elmlund et al., 2006; Knuesel et al., 2009a). The fundamental importance of CDK8 is reflected in its requirement for embryonic development in flies and mice (Loncle et al., 2007; Westerling et al., 2007). The kinase activity of CDK8 appears essential for its biological function. For example, CDK8 was identified as a colon cancer oncogene, and oncogenesis was dependent upon kinase activity (Firestein et al., 2008; Morris et al., 2008). Although only a few CDK8 targets have been identified, each, such as transcription factors and histone H3, can be considered as chromatin associated (Taatjes, 2010).

Here, we show that CDK8 phosphorylates S727 of the STAT1 TAD in response to IFN-γ. In vitro kinase assays and cell-based gene-silencing experiments demonstrate that CDK8, but not other chromatin-associated kinases such as CDK7 (TFIIH) or CDK9 (P-TEFb), is a STAT1 S727 kinase in the canonical IFN-γ-induced signaling pathway. Furthermore, CDK8 phosphorylates the TADs of other STAT family members. CDK8 is recruited to IFN-γ-regulated promoters in a STAT1-dependent fashion, and CDK8 occupancy correlates with STAT1 S727 phosphorylation. Microarray analyses indicate that phosphorylation of STAT1 S727 has different effects at different IFN-γ-induced genes: some genes show decreased expression and others show increased expression in STAT1 S727A mutant cells. IFN-γ-induced genes that are sensitive to STAT1 S727 phosphorylation show altered RNAPII occupancy that correlates with expression. Interestingly, expression of approximately half of IFN-γ-induced genes is not altered by S727 phosphorylation, despite evidence for occupancy of S727-phosphorylated STAT1 at the promoter after IFN-γ stimulation. CDK8-silencing experiments employing transcriptome-wide expression analysis demonstrate a generally positive role for CDK8 in IFN-γ responses. Cell-based virus-infection experiments reveal a requirement for CDK8 in IFN-γ-mediated establishment of antiviral responses, thereby further underlining a fundamental role for CDK8 in IFN biology. Together, the data show that CDK8 acts to regulate IFN-γ responses with gene-selective effects on STAT1 function. These findings also suggest a general role for CDK8 in cytokine signaling as a TAD kinase for other STATs.

Results

A Nuclear CDK Mediates Canonical TAD Serine Phosphorylation of STAT1 and Other STATs

Recent studies by us and others have revealed that cytokine-induced S727 phosphorylation of STAT1 and STAT3 TADs is restricted to promoter-bound transcription factors (Sadzak et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2010). These findings suggest that TAD phosphorylation is catalyzed by a nuclear kinase in a chromatin-associated signaling event. CDK7, CDK8, and CDK9 are nuclear kinases directly involved in the regulation of transcription by RNAPII (Egloff and Murphy, 2008). To begin to assess whether CDK7, CDK8, and/or CDK9 might mediate STAT1 phosphorylation, we probed STAT1 S727 phosphorylation levels in response to flavopiridol, a CDK inhibitor with increased specificity for CDK8 and CDK9 (Chao and Price, 2001; Rickert et al., 1999). Flavopiridol blocked IFN-γ- and IFN-β-induced S727 phosphorylation of STAT1 in murine bone-marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) (Figure 1A). Similar effects were observed in mouse fibroblasts treated with IFNs (Figure S1A, available online), as well as in human HepG2 cells treated with IFN-γ or IL-6 (Figure 1B), indicating tissue- and organism-independent involvement of a nuclear CDK. The CDK inhibitors roscovitine and olomoucine, which inhibit CDK functioning in the cell cycle (Alessi et al., 1998), did not diminish IFN-induced S727 phosphorylation (Figure 1C). Importantly, flavopiridol inhibited only the canonical (i.e., IFN-induced) S727 phosphorylation, shown by the fact that the noncanonical LPS-induced p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-driven S727 phosphorylation (Kovarik et al., 1999) was not altered by the inhibitor (Figure 1D). Similarly, treatment of fibroblasts with the stress inducer anisomycin resulted in STAT1 S727 phosphorylation that was refractory to flavopiridol (Figure S1B). Inhibition of IFN-γ-induced S727 phosphorylation by flavopiridol was dose dependent (Figure S1C).

Figure 1.

Canonical Cytokine-Induced TAD Phosphorylation of STAT1, STAT3, STAT4, and STAT5 Is Inhibited by Flavopiridol

(A) BMDMs were stimulated for 40 min with IFN-γ or IFN-β after pretreatment or control treatment for 15 min with flavopiridol (FP) (500 nM). Cell extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against phosphorylated STAT1 at S727 (pS727-STAT1) or Y701 (pY701-STAT1) and against total STAT1. Note the presence of two bands detected by the pY701-STAT1 antibody; they represent pY701 of STAT1α and STAT1β isoforms, which are both expressed in BMDMs. STAT1β has Y701 but lacks the TAD (including S727).

(B) Human HepG2 cells were stimulated for 30 min with IFN-γ or IL-6 after a 15 min pretreatment with FP. Cell extracts were analyzed as in (A).

(C) BMDMs were stimulated for 40 min with IFN-γ after a 15 min pretreatment with FP, olomoucine (Olo), or roscovitine (Rosc). Cell extracts were analyzed as in (A).

(D) BMDMs were stimulated for 40 min with LPS or IFN-γ after a 15 min pretreatment with FP. Cell extracts were analyzed as in (A).

(E) Sequence alignment of STAT C termini comprising the TADs of STAT1, STAT3, STAT4, and STAT5a. The conserved P(M)SP motif containing the serine residue phosphorylated upon cytokine stimulation is highlighted.

(F) BMDMs were stimulated for 40 min with LPS, IFN-β, or IL-10 after pretreatment or control treatment for 15 min with FP. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with antibodies against STAT3 and were subsequently analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against phosphorylated STAT3 at S727 (pS727-STAT3) or Y705 (pY705-STAT3) and against total STAT3.

(G) Mouse splenocytes were stimulated for 40 min with IL-12 or IFN-β after pretreatment or control treatment for 15 min with FP. Cell extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against phosphorylated STAT4 at S722 (pS722-STAT4) or Y694 (pY694-STAT4) and against total STAT4.

(H) BMDMs were stimulated for 40 min with GM-CSF after pretreatment or control treatment for 15 min with FP. Cell extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against STAT5a phosphorylated at S725 (corresponding to S730 in STAT5b) or Y694 (Y699 in STAT5b) and against total STAT5.

See also Figure S1.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays confirmed that flavopiridol-dependent reduction of S727 phosphorylation did not result from diminished STAT1 promoter binding (Figure S1D). Flavopiridol is known to globally inhibit transcription by RNAPII at 300 nM or higher (Chao and Price, 2001). Because we used flavopiridol at 500 nM, we asked whether a general blockade of RNAPII-dependent transcription was responsible for the inhibition of IFN-γ-induced phosphorylation. Treatment of cells with the transcription inhibitor actinomycin D demonstrated that IFN-γ-induced S727 phosphorylation was independent of ongoing transcription (Figure S1E).

Canonical cytokine-induced serine phosphorylation of STAT1, STAT3, STAT4, and STAT5 occurs on conserved motifs located in otherwise divergent TADs (Figure 1E). Phosphorylation of STAT1 on S727, STAT3 on S727, and STAT4 on S721 occurs in a PMSP motif (Morinobu et al., 2002; Wen et al., 1995). The corresponding phosphorylated serines are S725 in STAT5a and S730 in STAT5b, and both are in a PSP motif (Friedbichler et al., 2010). The sequence similarities and the requirement for chromatin binding of both STAT1 and STAT3 in cytokine-induced TAD phosphorylation suggest that STAT TAD phosphorylation might occur by a conserved mechanism.

We examined the role of nuclear CDKs in the canonical phosphorylation of other STATs by employing flavopiridol. Flavopiridol inhibited both IFN-β- and IL-10-induced S727 phosphorylation of STAT3 in BMDMs (Figure 1F). Importantly, only the cytokine-induced (i.e., canonical) S727 phosphorylation was inhibited by flavopiridol, whereas the LPS-induced MAPK-driven phosphorylation (Kovarik et al., 2001) remained unchanged (Figure 1F). Similarly, IL-12- and IFN-β-induced S721 phosphorylation of STAT4 in splenocytes was sensitive to flavopiridol (Figure 1G). STAT5 TAD phosphorylation was assessed by treatment with granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). GM-CSF-induced S725 phosphorylation of STAT5a (and the corresponding S730 in STAT5b) in BMDMs was inhibited by flavopiridol (Figure 1H), thereby resembling canonical TAD phosphorylation of other STATs.

Together, these findings reveal that in cytokine-induced (canonical) responses—conditions causing STAT phosphorylation on both tyrosine and TAD serine—the STAT TAD serine kinase(s) is a flavopiridol-sensitive nuclear kinase. Consistently, noncanonical TAD phosphorylation, which is known to depend on MAPKs and occurs without concomitant tyrosine phosphorylation, was not impaired by flavopiridol treatment.

CDK8 Phosphorylates S727 in STAT1 TAD in Response to IFN-γ and Is a TAD Kinase of Other STATs

To further characterize the STAT1 TAD kinase, we silenced genes for the known flavopiridol-sensitive nuclear kinases CDK7, CDK8, and CDK9 in fibroblasts by using siRNA (Figure 2A). Silencing of Cdk8, but not Cdk7, resulted in a reduction of IFN-γ-induced STAT1 S727 phosphorylation (Figure 2B). Silencing of Cdk9 also resulted in a reduction of S727 phosphorylation, although it was less pronounced that that of Cdk8 (Figure 2B and Figure S2A). Compared to silencing of Cdk8 alone, simultaneous silencing of both Cdk8 and Cdk9 did not result in a further decrease in IFN-γ-induced S727 phosphorylation (Figure S2B). Because CDK9 physically and functionally interacts with the CDK8 module (Donner et al., 2010; Ebmeier and Taatjes, 2010), decreased S727 phosphorylation in Cdk9-silenced cells might reflect their functional interdependence.

Figure 2.

CDK8 Phosphorylates S727 of STAT1 in IFN-γ Response

(A) Treatment of mouse fibroblasts with siRNA to Cdk7, Cdk8, and Cdk9 resulted in the reduction of the corresponding protein levels. Control siCtrl (Ctrl) had no effect. Fibroblasts were treated for 48 hr with their respective siRNA, and the protein amounts of CDK7, CDK8, or CDK9 were subsequently detected by immunoblotting. Antibodies against ERK1 and ERK2 (panERK) were used for the loading control.

(B) Silencing of Cdk8 reduced IFN-γ-induced STAT1 S727 phosphorylation. Fibroblasts silenced for the expression of Cdk7, Cdk8, or Cdk9 were treated for 40 min with IFN-γ or were left untreated. Cell extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against phosphorylated STAT1 at S727 (pS727-STAT1) or Y701 (pY701-STAT1) and against total STAT1.

(C and D) The CDK8 module phosphorylated the STAT1 TAD in vitro at S727.

(C) Kinase assays using the CDK8 module, TFIIH, and P-TEFb kinase complexes with STAT1 TAD (STAT1 WT), STAT1 TAD with the S727A alteration (STAT1 S727A), or RNAPII C-terminal domain (Pol II CTD) as substrates. Note that all kinase substrates have an N-terminal GST tag. The autorad image and silver-stained loading reference are shown for each substrate.

(D) Quantitation of kinase activity for the CDK8 module (CDK8), TFIIH, and P-TEFb against STAT1 WT and STAT1 S727A. All activities were standardized to the CDK8 STAT1 WT autorad signal (100). Asterisks denote signals that could not be integrated above the background signal; these were given a relative activity of zero. Shown are representative data from two independent experiments for each kinase. All quantitation was done with ImageJ.

(E) Silencing of Cdk8 with siCdk8 (left panel) and Ccnc with CycC (right panel) resulted in a similar reduction of IFN-γ-induced STAT1 S727 phosphorylation. siCdk8- or siCycC-silenced mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) or control (ctrl)-silenced cells were treated for 20 or 40 min with IFN-γ or were left untreated. Cell extracts were analyzed as in (B).

(F) Kinase assays using the CDK8 module, TFIIH, and P-TEFb complexes against substrates STAT3 TAD (S3 WT), S727A STAT3 TAD (S3 S727A), STAT5a TAD (S5 WT), S725A STAT5a TAD (S5 S725A), S779A STAT5a TAD (S5 S779A), and S725A-S779A STAT5a TAD (S5 S725/S779A). All kinase substrates have an N-terminal GST tag. The autorad image and silver-stained loading reference are shown for each substrate.

(G) Quantitation of kinase activity (obtained with ImageJ) for the CDK8 module against STAT3 and STAT5a TADs and the corresponding mutants described in (F). The activities were standardized at 100% for STAT3 WT or STAT5a WT. Error bars represent SDs (n = 3).

(H) Silencing of Cdk8 reduced IFN-β-induced STAT3 S727 phosphorylation. Cdk8-silenced fibroblasts were treated for 40 min with IFN-β or were left untreated. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with STAT3 antibodies and analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against phosphorylated STAT3 at S727 (pS727-STAT3) or Y705 (pY701-STAT3) and against total STAT3.

See also Figure S2.

To more definitively assess whether CDK7, CDK8, and/or CDK9 were phosphorylating STAT1 S727, we completed a series of in vitro kinase assays. Purified TFIIH (containing active CDK7), CDK8 module (containing active CDK8), and P-TEFb (containing active CDK9) were used (Figure S2C). The kinase substrate included recombinantly expressed wild-type (WT) or S727A mutant STAT1 TAD. The C-terminal domain (CTD) of the large subunit of RNAPII was included as a positive control because all three kinases are each known to phosphorylate the RNAPII CTD in vitro (Knuesel et al., 2009b; Wada et al., 1998; Yankulov and Bentley, 1997). The CDK8 module was capable of phosphorylating WT STAT1 TAD (Figures 2C and 2D), but not the S727A STAT1 mutant, indicating CDK8 specificity for this site (Figures 2C and 2D).

To further assess the role of CDK8 in IFN-γ-induced S727 phosphorylation, we silenced Ccnc, encoding CycC (Figure S6D), a regulatory subunit of CDK8 (Donner et al., 2010). Compared with Cdk8-silenced cells, Ccnc-silenced cells exhibited a similar and, over time, stable reduction of IFN-γ-induced S727 phosphorylation (Figure 2E). Noncanonical S727 phosphorylation was not influenced by Cdk8 silencing (Figure S2D). These results indicate a key role for CDK8 in IFN-γ-induced S727 phosphorylation.

We next asked whether CDK8 plays a more general role in JAK-STAT signaling, i.e., by phosphorylating the TADs of other STATs. First, we employed kinase assays by using recombinantly expressed TADs of WT STAT3, S727A mutant STAT3, WT STAT5a, S725A mutant STAT5a, S779A mutant STAT5a, and S725A-S779A double-mutant STAT5a. The STAT5a TAD contains two serines (S725 and S779) that can be phosphorylated in cells, but only S725 is conserved in STAT5a and STAT5b, whereas S779 occurs only in STAT5a (Friedbichler et al., 2010). The S725 residue is located in a PSP sequence that resembles the conserved PMSP motif found in STAT1, STAT3, and STAT4 (Figure 1E), whereas S779 is located within a distinct LSP motif. The CDK8 module phosphorylated only the TADs of WT STAT3, WT STAT5a, and S779A mutant STAT5a, but not those of S727A mutant STAT3, S725A mutant STAT5, or S725A-S779A double mutant STAT5 (Figures 2F and 2G), indicating that S727 of STAT3 and S725 of STAT5a are CDK8 substrates. TFIIH and P-TEFb did not phosphorylate the STAT3 or STAT5a TADs (Figure 2F), thereby revealing the same specific nature of the CDK8-mediated phosphorylation as observed for the STAT1 TAD (Figures 2C and 2D). Silencing experiments confirmed CDK8-mediated phosphorylation of S727 within the STAT3 TAD in vivo (Figure 2H).

In summary, these results demonstrate a general role for CDK8 in phosphorylation of TADs within the STAT family.

Recruitment of CDK8 to IFN-γ Target Genes Requires STAT1 and Depends upon STAT1 S727 Phosphorylation

Our previous finding that IFN-γ-induced S727 phosphorylation occurred only on promoter-bound STAT1 (Sadzak et al., 2008) prompted us to examine recruitment of CDK8 to the STAT1-regulated Irf1 promoter. Upon IFN-γ treatment, CDK8 gradually associated with the Irf1 transcription start site (TSS) and peaked after 30 min (Figure 3A, left panel). CDK8 recruitment was STAT1 dependent because the CDK8 signal did not increase in equally treated STAT1-deficient cells (Figure 3A, right panel). Further, CDK8 was not increased 8 kb downstream of the Irf1 TSS (Figure S3E), consistent with the association between CDK8 and the promoter-bound Mediator complex. STAT1 recruitment at Irf1 initiated with a sharp increase 5 min after IFN-γ treatment and peaked at 20 min (Figure 3B, left panel), slightly before maximal accumulation of CDK8. The IFN-γ-induced appearance of S727-phosphorylated STAT1 at the Irf1 promoter was not clearly detectable earlier than 20 min after IFN-γ stimulation; thus, it followed promoter recruitment of STAT1 and CDK8 with an approximately 10–15 min delay (Figure 3B, right panel). These results indicate that STAT1 is required for CDK8 recruitment to Irf1 and further support CDK8 as the STAT1 S727 kinase.

Figure 3.

CDK8 Recruitment to IFN-γ Target Genes Requires STAT1 and Depends on S727

(A) CDK8 recruitment is dependent on IFN-γ (left panel) and STAT1 (right panel). WT MEFs (left panel) or WT and Stat1−/− MEFs (right panel) were treated with IFN-γ, and CDK8 recruitment to the Irf1 TSS was determined by ChIP. CDK8 was slowly recruited with peak appearance after 30 min of stimulation (left panel). No increase of CDK8 was detected at Irf1 in Stat1−/− MEFs (right panel). Immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by qPCR for the Irf1 TSS. Signals were normalized to input DNA. Error bars represent SDs (n = 3).

(B) STAT1 recruitment (left panel) and slower increase in S727-phosphorylated STAT1 occupancy at the Irf1 promoter (right panel). WT MEFs were treated with IFN-γ, and STAT1 (left panel) or S727-phosphorylated STAT1 (right panel) at the Irf1 promoter was determined by ChIP. Signals were normalized to input DNA. Error bars represent SDs (n = 3).

(C) CDK8 was recruited to Irf1 (left panel) and Gbp2 (right panel); the STAT1 S727A alteration reduced CDK8 recruitment to both genes. STAT1 WT and STAT1 S727A MEFs were treated with IFN-γ. The association between CDK8 and the Irf1 and Gbp2 TSSs was examined by ChIP. Signals were normalized to input DNA. Error bars represent SDs (n = 3).

(D) The STAT1 WT and the S727A mutant were similarly recruited to the IFN-γ-regulated promoters. WT and S727A MEFs were treated for 1 hr with IFN-γ or were left untreated. The association between STAT1 and the Irf1 and Gbp2 promoters was examined by ChIP. Immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by qPCR for the Irf1 and Gbp2 promoters (comprising the GAS elements). Signals were normalized to input DNA. Error bars represent SDs (n = 3).

(E) CDK8 was less efficiently recruited by STAT1β than by STAT1α. MEFs derived from mice expressing solely STAT1α or STAT1β were treated with IFN-γ. The association between CDK8 and the Irf1 and Gbp2 TSSs was examined by ChIP as in (C). Error bars represent SDs (n = 3).

See also Figure S3.

Whereas IFN-γ-induced expression of Gbp2 and Tap1 is sensitive to the STAT1 S727A alteration, expression of Irf1 is not (Kovarik et al., 2001; Varinou et al., 2003). ChIP assays demonstrated that S727-phosphorylated STAT1 accumulated at the Gbp2 and Tap1 promoters (Figures S3A and S3C, right panels) with a 10–15 min delay after STAT1 recruitment (Figures S3A and S3C [left panels] and Figures S3B and S3D); this delay was the same as that observed for the Irf1 promoter (Figure 3B). The plateau of association between S727-phosphorylated STAT1 and chromatin was reached after approximately 60 min of IFN-γ treatment (Figure S3F). A similar accumulation of S727-phosphorylated STAT1 at the S727-sensitive (i.e., Gbp2 and Tap1) and -insensitive (i.e., Irf1) promoters established that the chromatin-associated STAT1 TAD phosphorylation occurred independently of its downstream effects on transcription. These results also indicate that the S727 kinase CDK8 was recruited to both types of genes. To ascertain this, we compared CDK8 occupancy at the Irf1 and Gbp2 promoters in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) derived from WT and S727A mice. CDK8 was recruited to both genes, but the S727A alteration resulted in a decreased CDK8 occupancy (Figure 3C). Recruitment of the S727A STAT1 mutant was not lower than that of WT STAT1 at Irf1 or Gbp2, confirming that the reduced CDK8 recruitment in S727A cells did not result from altered STAT1 promoter binding (Figure 3D).

To test whether STAT1 fully devoid of the TAD was able to recruit CDK8, we employed MEFs expressing solely the STAT1α isoform or the natural splice variant lacking the TAD (STAT1β). Compared to STAT1α, the STAT1β isoform displayed reduced CDK8 recruitment (Figure 3E). Similarly, the occupancy of the Mediator complex (generally needed for CDK8 recruitment [Elmlund et al., 2006; Knuesel et al., 2009a]) and RNAPII at Irf1 were also reduced in STAT1β cells (Figure S3G). Thus, both the S727A alteration and the complete lack of the TAD resulted in diminished CDK8 recruitment.

The STAT1 S727A Alteration Positively or Negatively Controls Expression of IFN-γ-Regulated Genes

The S727A alteration was previously reported to reduce expression of several IFN target genes (Kovarik et al., 2001; Varinou et al., 2003), whereas the contribution of CDK8 to IFN-γ responses was unknown. To determine the transcriptome-wide effect of STAT1 TAD phosphorylation on IFN-γ-regulated gene expression and the role of CDK8 therein, we conducted microarray-based analysis by using WT and S727A STAT1 MEFs treated with Cdk8 siRNA (siCdk8) or with control siRNA (siCtrl). Gene expression was analyzed in MEFs stimulated with IFN-γ for 0 and 4 hr. We first evaluated the effect of S727 phosphorylation by examining the microarray data from siCtrl cells. The analysis of the effect of Cdk8 silencing is described later. Microarray data are accessible at the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE40728.

Among 256 genes (p value < 0.05) whose expression was induced by IFN-γ at least 2-fold in WT MEFs (Table S4), we identified genes that displayed at least 2-fold higher expression in WT MEFs than in S727A MEFs (Tables S1–S4). Expression of 61 genes was less induced in S727A MEFs (Figure 4A and Table S1), expression of 48 genes was higher in S727A MEFs than in WT MEFs (Figure 4A and Table S2), and expression of 147 genes was not significantly different between S727A cells and WT cells (Figure 4A and Table S3). The microarray results were validated by qRT-PCR analysis for a subset of IFN-γ-induced genes (Figure 4B). In total, the absence of IFN-γ-induced S727 phosphorylation resulted in altered expression of more than 40% of IFN-γ-regulated genes. Importantly, the absence of S727 phosphorylation resulted not only in decreased expression of some IFN-γ-regulated genes but also, unexpectedly, increased expression of others.

Figure 4.

CDK8-Mediated STAT1 S727 Phosphorylation Is Required for Balanced Induction of IFN-γ-Regulated Genes

(A) Out of 256 IFN-γ-induced genes, 61 were less expressed and 48 were more expressed in the absence of S727 phosphorylation. WT and S727A MEFs were stimulated for 4 hr with IFN-γ or were left untreated. mRNA from three biological replicates was analyzed with microarrays. First, genes significantly (p value < 0.05) induced at least 2-fold by IFN-γ were selected. Expression of these genes was compared between WT and S727A cells. At least 2-fold different expression (p value < 0.05) was found for 109 genes, 61 of which displayed lower expression and 48 of which higher expression in S727A cells.

(B) qRT-PCR validation of microarray data. WT and S727A MEFs were stimulated for 2 and 4 hr with IFN-γ or were left untreated. mRNA of Irf1, Tap1, Gbp2, Irf8, and Isg15 was analyzed by qRT-PCR. Irf1 was equally expressed, expression of Tap1, Gbp2, and Irf8 was reduced, and Isg15 expression was higher in S727A cells. Error bars display SDs of biological replicates (n = 3).

See also Tables S1–S4.

The so-called primary IFN-γ-induced genes depend solely on STAT1 for their expression, whereas secondary IFN-γ-induced genes require cooperation of STAT1 with additional transcription factors, particularly IFN regulatory factor (IRF) family members, which are themselves regulated by IFN (Levy and Darnell, 2002). Primary Irf1, Wars (also known as Ifp-53), and Ifi47 are each regulated by binding of the STAT1 homodimer to the IFN-γ-activated sequence (GAS) in the promoter (MacMicking et al., 2003; Pine et al., 1994; Strehlow et al., 1993). These are the genes whose expression upon IFN-γ stimulation was not significantly affected by the S727A alteration (Tables S3 and S4). Genes that were less expressed in S727A cells than in WT cells include Gbp2, Gbp4, Tap1, and Ccl2 (Tables S1 and S4); each of these genes contains other DNA regulatory elements, most importantly IFN-stimulated response elements (ISREs), in addition to GAS elements (Lew et al., 1991; MacMicking, 2004). On the other hand, Irf8 was less expressed in S727A cells (Figure 4 and Tables S1 and S4), yet its induction by IFN-γ was mediated by a GAS element, but not ISREs (Kantakamalakul et al., 1999). The group of genes upregulated by IFN-γ in S727A MEFs compared to WT MEFs includes Isg15, Ifi203, and Ifi204 (Tables S2 and S4). These genes are principally regulated by ISREs rather than by GAS elements (Kubosaki et al., 2010; Mamane et al., 2002). As these examples demonstrate, no good correlation exists between the effects of the S727A alteration and primary or secondary IFN-γ target-gene expression, although secondary genes appear to be more sensitive to S727 phosphorylation.

The STAT1 S727A Alteration and the RNAPII Transcription Rate

To determine whether the STAT1 S727A alteration might impact the rate of transcription, we measured RNA synthesis at different time points after stimulation with IFN-γ by employing 4-thiouridine (4sU) metabolic labeling of newly transcribed RNA (Dölken et al., 2008). We added 4sU to the cells either simultaneously with IFN-γ or 60 or 210 min after IFN-γ stimulation or without IFN-γ treatment. The metabolic labeling was performed for 30 min. Given that the mRNA half-lives were higher than the 30 min labeling interval (Figure S4A), the amount of labeled RNA was proportional to the RNA transcribed during each interval. The 4sU-labeled RNA fraction was separated from total RNA. Aliquots of total RNA were saved before separation. The amount of total mRNA of Irf1, Tap1, Gbp2, Irf8, and Isg15 (Figure S4B) was similar to mRNA levels determined in a standard experiment (i.e., no 4sU) (Figure 4B), demonstrating the consistency of both methods. Analysis of the labeled fractions revealed that the rate of mRNA synthesis in the 30 min labeling periods (Figure 5) reflected the amount of total mRNA in both WT and S727A cells (Figure S4B) for all analyzed genes except for Irf1. The amount of labeled Irf1 mRNA was reduced by approximately one-third in S727A cells compared to WT cells. Such differences were not reflected in total RNA measurements as a result of permanent mRNA turnover. Primary transcript measurements confirmed that the effects of the S727A alteration resulted from changes in transcription (Figure S4C). These data demonstrate a gene-selective role for STAT1 S727 phosphorylation in controlling the transcription rate.

Figure 5.

Detection of IFN-γ-Induced Gene Expression in WT and S727A Cells by Analysis of Newly Transcribed RNA

4sU was added to the cell-culture medium simultaneously with IFN-γ, 60 and 210 min after IFN-γ stimulation, or without IFN-γ treatment. Labeling was performed in WT and S727A MEFs for 30 min and was followed by RNA isolation and separation for the collection of the 4sU-labeled RNA fractions and total RNA fractions. The labeled RNA fractions represented RNA that was synthesized during a 30 min interval before stimulation of cells, as well as in the periods 0–30 min, 60–90 min, and 210–240 min after IFN-γ treatment. The amount of Irf1, Tap1, Gbp2, Irf8, and Isg15 mRNA was measured in the labeled (i.e., newly synthesized) fractions by qRT-PCR. ActB was used for normalization. Error bars represent SDs (n = 3).

See also Figure S4.

Gene-Selective Role of STAT1 S727 Phosphorylation on RNAPII

To better understand the gene-specific role of CDK8-mediated STAT1 S727 phosphorylation on the transcription of IFN-γ-induced genes, we selected Irf1, a GAS-driven IFN-γ target gene, as well as the GAS- and ISRE-controlled IFN-γ target genes Gbp2 and Tap1, for detailed analysis (Figure S5A). We examined the recruitment of RNAPII at the TSSs of Irf1, Gbp2, and Tap1 in WT and S727A MEFs. RNAPII was recruited to the Irf1 TSS equally well in IFN-γ-treated WT and S727A cells (Figure 6A, left panel). By contrast, occupancy of RNAPII at the Tap1 and Gbp2 TSSs was lower in S727A cells than in WT controls (Figure 6A, middle and right panels). These data are in agreement with the diminished IFN-γ-induced expression of Gbp2 and Tap1 but unchanged Irf1 expression in S727A MEFs (Figure 4B).

Figure 6.

STAT1 S727 Phosphorylation Controls Chromatin Recruitment of RNAPII and S2-Phosphorylated RNAPII in a Gene-Specific Manner

(A) Association between RNAPII and the TSSs of Irf1, Tap1, and Gbp2 in WT and S727A MEFs treated for 1 and 2 hr with IFN-γ was examined by ChIP with RNAPII antibodies. Immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by qPCR for the Irf1, Gbp2, and Tap1 TSSs. Signals were normalized to input DNA. Error bars represent SDs (n = 3).

(B and C) Association between RNAPII and S2-phosphorylated RNAPII and the gene body (intron 8) of Irf1 (B) and the gene body (intron 5) of Tap1 (C) in WT and S727A MEFs treated for 1 and 2 hr with IFN-γ was examined by ChIP with antibodies against RNAPII (left panels) and pS2-RNAPII (middle panels). Immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by qPCR for Irf1 intron 8 and Tap1 intron 5. Signals were normalized to input DNA. Error bars represent SDs (n = 3). Right panels depict the ratios of pS2-RNAPII to total RNAPII.

See also Figure S5.

Relative abundance of S2-phosphorylated RNAPII (i.e., after normalization to total RNAPII) in the gene bodies of transcribed genes provides a robust estimate of transcription elongation. We analyzed the presence of RNAPII and S2-phosphorylated RNAPII at the gene bodies of Irf1 (intron 8) and Tap1 (intron 5), i.e., at positions approximately 5.6 kb and 4.2 kb, respectively, downstream of their respective TSSs (Figure S5A). RNAPII was present at comparable amounts in WT and S727A cells, and S2-phosphorylated RNAPII was slightly reduced by the S727A alteration (Figure 6B). After normalization to total RNAPII, the reduction of S2-phosphorylated RNAPII in the Irf1 gene body in S727A cells became more apparent (Figure 6B, right panel), which is in line with the slower rate of RNA synthesis detected by 4sU labeling (Figure 5A). In the case of Tap1, both RNAPII and S2-phosphorylated RNAPII associated with the gene body in S727A cells to a much lesser extent than in WT cells (Figure 6C). The lower abundance of S2-phosphorylated RNAPII within Tap1 remained pronounced in the S727A cells after normalization to the total RNAPII (Figure 6C, right panel). The data are consistent with the strong effect of S727 phosphorylation on Tap1 mRNA levels and the lack of such an effect in the case of Irf1. As expected, comparison of the ratios of S2-phosphorylated RNAPII to total RNAPII showed lower relative occupancy of S2-phosphorylated RNAPII at the TSS relative to the gene body for both Irf1 and Tap1 (Figure S5B). Collectively, these data demonstrate that despite general recruitment of CDK8 and the subsequent presence of S727-phosphorylated STAT1 at IFN-γ target promoters, the precise downstream effects on RNAPII recruitment and RNAPII phosphorylation are gene specific.

CDK8 Is a Broad Regulator of IFN-γ-Induced Gene Expression and Is Required for Antiviral Response

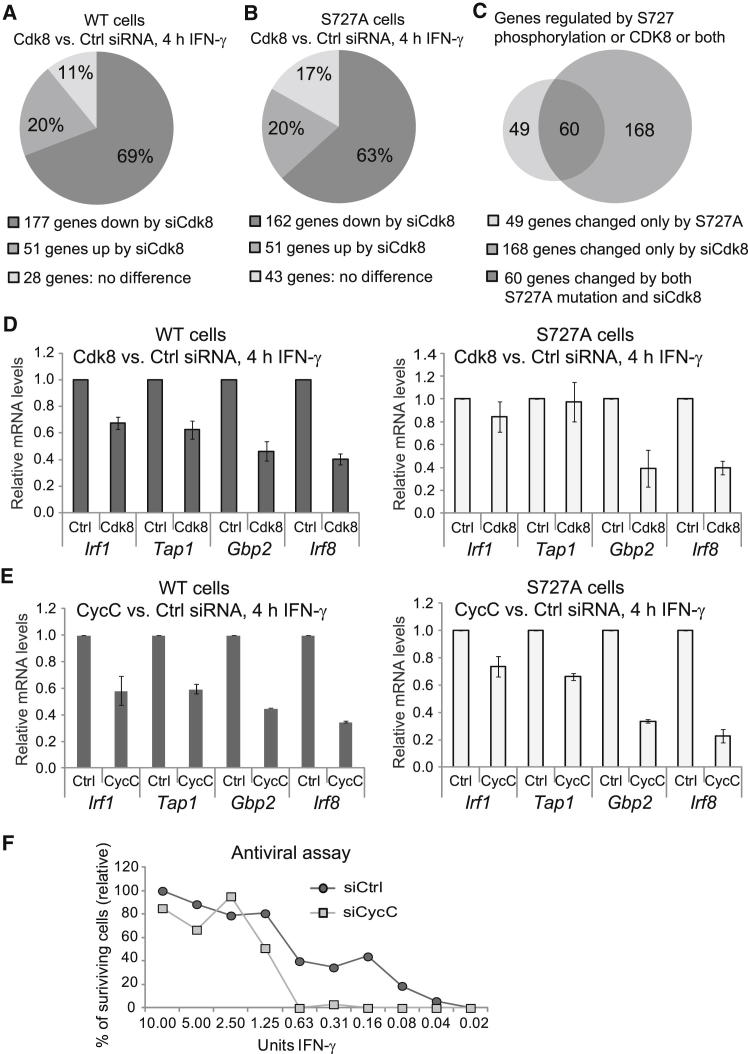

CDK8 can positively or negatively impinge on transcription by acting as both a kinase and a structural component within the Mediator complex (Taatjes, 2010). To further confirm the role of CDK8 in controlling IFN-γ responses via STAT1 S727 phosphorylation, we silenced Cdk8 expression and compared IFN-γ-induced gene expression in STAT1 WT and S727A cells by using microarrays. Cells were treated with siCdk8 or siCtrl and were subsequently stimulated with IFN-γ for 4 hr. Silencing efficiency was approximately 90% in both WT and S727A cells (Figure S6A). Importantly, the siRNA transfection procedure did not itself result in any changes in Cdk8 expression (Figure S6B). IFN-γ-induced gene expression profiles revealed that in STAT1 WT cells, Cdk8 silencing resulted in downregulation of 69% of IFN-γ-stimulated genes (Figure 7A and Table S4, column 8). Similar effects were observed in STAT1 S727A cells (Figure 7B and Table S4, column 9). As expected, the microarray experiment identified IFN-γ-induced gene expression changes shared by S727A cells and Cdk8-silenced cells (Figure 7C and Table S5). The overlap, which represents 55% of all S727-regulated genes and includes Tap1, Gbp2, and Irf8, contained 60 genes, of which 43 were downregulated and 17 were upregulated (Table S5).

Figure 7.

The CDK8 Module Regulates Most IFN-γ-Induced Genes and Impairs Antiviral Response

(A and B) Most IFN-γ-induced genes were downregulated by Cdk8 silencing in both STAT1 WT and S727A cells. STAT1 WT (A) or S727A (B) MEFs were treated with siCdk8 or siCtrl and were stimulated for 4 hr with IFN-γ or were left untreated. mRNA from three biological replicates was analyzed with microarrays. Out of 256 IFN-γ-induced genes, 177 (69%) were less expressed in WT STAT1 cells treated with siCdk8 than in siCtrl treated cells (A). In STAT1 S727A cells, 162 genes (63%) were less expressed by siCdk8 (B). The numbers were extracted from Table S4.

(C) Overlap of genes similarly regulated by S727 phosphorylation and CDK8. The left circle shows IFN-γ-induced genes that were significantly changed (upregulated or downregulated) in S727A cells. The right circle shows IFN-γ-induced genes that changed (upregulated or downregulated) upon Cdk8 silencing in WT cells. The overlap depicts genes (60 in total) that were either downregulated or upregulated by both the S727A alteration and Cdk8 silencing. The numbers were extracted from Table S4.

(D) Validation of microarray data. WT or S727A MEFs treated with siCdk8 or siCtrl were stimulated for 4 hr with IFN-γ or were left unstimulated, and mRNA for Irf1, Tap1, Gbp2, and Irf8 was analyzed by qRT-PCR. For each gene, mRNA was normalized to Hprt mRNA and standardized to 1.0 for the siCtrl-treated samples. Error bars display SDs of biological replicates (n = 3).

(E) The effect of Ccnc silencing (with siCycC) on IFN-γ-regulated genes was similar to that of Cdk8 silencing. WT or S727A MEFs treated with siCycC or siCtrl were stimulated for 4 hr with IFN-γ or were left unstimulated. mRNA for Irf1, Tap1, Gbp2, and Irf8 was analyzed by qRT-PCR. For each gene, mRNA was normalized to Hprt mRNA and standardized to 1.0 for the siCtrl-treated samples. Error bars represent SDs (n = 3).

(F) Silencing of Ccnc with siCycC resulted in increased sensitivity of cells to VSV infection. STAT1 WT cells were treated with siCycC or siCtrl and were incubated with IFN-γ at the indicated concentrations. After 24 hr of IFN-γ treatment, cells were infected with vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) (multiplicity of infection = 0.1) for 39 hr. Cell survival was then evaluated with crystal-violet staining. Mean crystal-violet values of duplicate experiments are shown.

Validation of the microarray data (Figure S6C) confirmed that the physical presence of CDK8 was generally required for full expression of both STAT1-S727-phosphorylation-dependent (Tap1, Gbp2, and Irf8) and -independent (Irf1) genes (Figure 7D). The STAT1-TAD-phosphorylation-independent contribution of CDK8 to IFN-γ-induced gene expression was gene specific (Figure 7D, right panel). Ccnc silencing reproduced the Cdk8-silencing experiment, although the differences were slightly bigger for Ccnc siRNA (siCycC) than for siCdk8 (Figure 7E). This is likely due to a reproducibly higher silencing efficiency obtained for Ccnc (98%) than for Cdk8 (Figures S6A and S6D). Controls revealed that silencing of Ccnc did not affect the expression of Cdk8 (Figure S6B).

The broad effect of CDK8 on IFN-γ-induced gene expression prompted us to test the biological role of the CDK8 module in IFN-γ responses by using vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) infection. We infected siCycC- and siCtrl-silenced cells pretreated with serial dilutions of IFN-γ. Because of a better silencing efficiency, Ccnc, rather than Cdk8, was chosen (Figures S6A and S6D). Ccnc silencing resulted in higher sensitivity to VSV and 10-fold higher IFN-γ requirement for efficient protection against VSV (Figure 7F). Control experiments demonstrated no effect of siRNA transfection on the sensitivity to VSV (Figure S6E). These findings establish that CDK8 function is required for IFN-γ-inducible antiviral responses.

Discussion

The identity of the chromatin-associated kinase that targets STAT1 S727 has long remained unknown; in this study, we established CDK8 as a STAT1 S727 kinase and a key component of the IFN-γ signaling pathway. Remarkably, CDK8-dependent STAT1 S727 phosphorylation was stimulus specific and restricted to canonical IFN-γ signaling, evident by the fact that noncytokine stimuli (e.g., LPS or anisomycin) were not sensitive to CDK8. CDK8 involvement in IFN-γ signaling resulted in downstream effects on transcription. These effects were gene specific; some genes were upregulated, and others were downregulated, providing an additional layer of control and modulation of IFN-γ-regulated gene expression. Indeed, these varied and selective CDK8 inputs appear to be required for the establishment of a functional antiviral response.

Our study established that CDK8-mediated STAT1 S727 phosphorylation regulates the expression of over 40% of IFN-γ-induced genes in MEFs. Surprisingly, the IFN-γ-induced gene expression was both positively and negatively modulated by STAT1 S727 phosphorylation. Expression of Irf1, Wars, and Ifi47, regulated primarily by STAT1 binding to GAS elements, was not sensitive to S727 phosphorylation. By employing metabolic labeling of newly transcribed RNA, however, we observed subtle effects of S727 phosphorylation on the rate of Irf1 transcription, suggesting that the impact of S727 phosphorylation on transcription does not exclude GAS-driven genes. This is further supported by the markedly reduced expression of the GAS-controlled Irf8 in the absence of S727 phosphorylation. Gbp2, Gbp4, Tap1, and Ccl2, which require STAT1 and IRF1 and depend on GASs and ISREs, needed S727 phosphorylation for full IFN-γ-induced expression. This, however, did not allow a general conclusion with regard to regulation by S727 phosphorylation given that Gbp5, which also contains ISREs and GAS elements (Nguyen et al., 2002), was not affected by the S727A alteration. Finally, genes primarily regulated by ISREs also displayed variable sensitivity to the S727A alteration; for example, expression of Isg15 was upregulated, whereas Oas1 expression was unchanged.

Collectively, the gene expression data reveal no direct correlation between the effects of STAT1 S727 phosphorylation and gene regulation by GASs, ISREs, or both DNA elements. This most likely reflects the presence of gene-specific coactivators or corepressors that differentially rely on STAT1 S727 phosphorylation for their recruitment and/or activity. One candidate-gene-selective coregulator is the Mediator complex, whose activity is regulated in various ways upon transcription factor binding (Ebmeier and Taatjes, 2010; Taatjes, 2010). The CDK8 module reversibly associates with Mediator on a genome-wide scale (Kagey et al., 2010; Knuesel et al., 2009a), and Mediator is generally recruited to regulatory loci by DNA-binding transcription factors. We observed a correlation between STAT1 S727 phosphorylation and CDK8 occupancy at IFN-γ-regulated genes. In fact, the effects of complete loss of the STAT1 TAD on CDK8 recruitment were similar to those of the S727A alteration. The dependence of CDK8 occupancy on STAT1 phosphorylation parallels the ELK-1 transcription factor, for which stimulus-specific ELK-1 phosphorylation enhanced Mediator occupancy at its target genes (Balamotis et al., 2009). Future studies could explore the mechanisms by which CDK8-dependent STAT1 phosphorylation regulates Mediator or other gene-specific coregulators at select target genes.

Consistent with its role as both a general and gene-selective regulator of transcription, CDK8 can regulate IFN-γ responses independently of STAT1 S727 phosphorylation. This was evident from comparative gene expression analyses, in which we observed significant, but not complete, overlap among genes impacted by Cdk8 silencing versus the STAT1 S727A alteration. Such results were not unexpected given the stark difference between physical loss of CDK8 and modification of a single CDK8 substrate (STAT1 S727). A total of 60 genes (55% of all STAT1-S727-regulated genes) were similarly impacted by Cdk8 silencing and the STAT1 S727A alteration. These genes are most likely directly regulated by the S727-targeted CDK8 activity. Genes that were differentially affected in the Cdk8-silencing and STAT1-S727A experiments probably depend on the physical presence of CDK8 or require CDK8 to act upon substrates other than STAT1 for normal IFN-γ-induced expression. Moreover, at least some genes differentially affected in Cdk8-silenced cells will result from indirect effects of CDK8 (e.g., elevated expression of a gene-selective STAT1 corepressor). A small number of S727A-regulated genes (15 in total) appeared unaltered by Cdk8 silencing. It remains possible that a distinct kinase, perhaps even the CDK8 paralog CDK19, might be acting at these genes.

STAT1 adds to the growing number of CDK8 substrates in Metazoa; these include CDK8 itself, cyclin H, MED13, histone H3, and the transcription factors E2F1, Notch, SMAD1/SMAD3, and SREBP (Akoulitchev et al., 2000; Alarcón et al., 2009; Fryer et al., 2004; Knuesel et al., 2009b; Meyer et al., 2008; Morris et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2012). Phosphorylation of SREBP or Notch by CDK8 and phosphorylation of Smads by CDK8 and/or CDK9 result in an increased turnover of these factors as a result of proteolytic degradation (Alarcón et al., 2009; Fryer et al., 2004; Zhao et al., 2012). STAT1 is not regulated in this way given that we observed that inhibition of S727 phosphorylation by flavopiridol or by the S727A alteration did not change the amount of promoter-bound STAT1.

STAT1 is phosphorylated by CDK8 at a serine residue followed by proline, thereby resembling the proline-directed serine phosphorylation of SMAD1, SMAD3, and the RNAPII CTD (Alarcón et al., 2009; Fryer et al., 2004; Knuesel et al., 2009b). Phosphorylation of cyclin H and histone H3 does not occur in a proline-directed fashion, suggesting relaxed substrate specificity of CDK8 toward proteins other than transcription factors (Akoulitchev et al., 2000; Meyer et al., 2008). The conserved PMSP sequence motif at the serine-phosphorylated sites within different STAT TADs suggests that a single kinase might phosphorylate multiple STATs. The shared sensitivity of STAT1, STAT3, STAT4, and STAT5 TAD phosphorylation to inhibition by flavopiridol and the ability of the CDK8 module to phosphorylate STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5 TADs demonstrate a general role for CDK8 in STAT TAD phosphorylation and suggest that CDK8 regulates the transcriptional activity of other STATs in a similar way as established here for STAT1.

Given the fundamental roles for STAT transcription factors in human growth and development, immune response, and cancer (Levy and Darnell, 2002), this work also identifies CDK8 as a therapeutic target within the STAT pathway. Diminished CDK8 function resulted in an impaired antiviral response, establishing a general requirement for CDK8 in IFN-γ responses. The ability of the CDK8 module—but not other chromatin-associated kinase complexes such as P-TEFb or TFIIH—to phosphorylate important regulatory sites within the STAT transcription factor family suggests a conserved role in regulating STAT activity during cytokine responses. Similar to our observations with STAT1, CDK8 has been shown to differentially regulate expression of subsets of genes within the serum response and WNT/β-catenin pathways (Donner et al., 2010; Firestein et al., 2008). In SREBP-regulated lipogenesis, CDK8 acts as a negative regulator (Zhao et al., 2012). Thus, despite being a cofactor of the general transcription machinery, CDK8 emerges as a surprisingly pathway-specific regulator of transcriptional networks. CDK8 requirement in cellular protection against viral infection suggests that CDK8-associated defects might contribute to immune disorders. Our work highlights a central role for CDK8 in STAT-dependent cytokine responses and its increasingly recognized suitability for therapeutic exploitation.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Culture

Primary MEFs were isolated from mice expressing WT STAT1 or the S727A mutant (Varinou et al., 2003) (both on C57BL/6N) and were immortalized via the 3T3 method (Todaro and Green, 1963) for the attainment of STAT1 WT and STAT1 S727A MEFs, respectively. STAT1 WT and STAT1 S727A MEFs, MEFs from Stat1−/− mice (Durbin et al., 1996) and human hepatocarcinoma HepG2 cells (ATCC number HB-8065) were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). Mouse BMDMs were isolated from the femur and tibia bone marrow of 6- to 10-week-old C57BL/6N mice. Macrophages were cultivated in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS in the presence of L929-cell-derived CSF-1 as previously described (Kovarik et al., 1998). Mouse splenic cells were isolated from spleens of 6- to 10-week-old C57BL/6N mice. Spleens were removed and squeezed through a 100 μm cell strainer. The single-cell suspension was than treated with red blood cell lysis buffer. The cells were expanded for 3–5 days in medium composed of RPMI-1640 containing L-glutamine and supplemented with 10% FCS, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, nonessential amino acids, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 100 U/ml IL-2 (all Sigma-Aldrich).

Cytokines and Inhibitors

For stimulations of cells, the following reagents were used: 5 or 10 ng/ml mouse IFN-γ (eBioscience), 100 U/ml mouse IFN-β (Calbiochem-Merck), 100 ng/ml anisomycin (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 ng/ml LPS from E. coli (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 ng/ml mouse IL-10 (eBioscience), 10 ng/ml mouse IL-6 (R&D Systems), 10 ng/ml mouse IL-12 (R&D Systems), X-6310-cell-derived GM-CSF as 1:2 dilution in DMEM with 10% FCS, 10 ng/ml human IFN-γ (R&D Systems), and 10 nM human IL-6 (R6D Systems). Flavopiridol was obtained through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIH National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and was used in a final concentration of 500 nM if not stated otherwise. Roscovitine and olomoucin (both Calbiochem-Merck) were used in a concentration of 50 μM, and 5 μg/ml actinomycin D (Sigma-Aldrich) was used.

Acknowledgments

We thank Thomas Decker for providing gene-targeted mice expressing the S727A STAT1 mutant for MEF isolation and Michaela Prchal-Murphy for splenocyte preparation. We thank David Price for expression vectors for CDK9 and cyclin T1 and Richard Moriggl for STAT5a plasmids. Recombinant insect cell expression was completed by the Tissue Culture Shared Resource at the University of Colorado Cancer Center. This work was supported by Austrian Science Fund grants W1220-B09 DP (“Molecular Mechanisms of Cell Signaling”) and P22806-B11 to P.K. and SFB F28 to M.M., University of Vienna grant Initiativkolleg I031-B to P.K., and National Cancer Institute grant R01 CA127364 to D.J.T. Z.C.P. was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health Predoctoral Training Grant (T32 GM08759).

Published: January 24, 2013

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes six figures, five tables, and Supplemental Experimental Procedures, and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2012.10.017.

Accession Numbers

The microarray data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE40728.

Supplemental Information

References

- Akoulitchev S., Chuikov S., Reinberg D. TFIIH is negatively regulated by cdk8-containing mediator complexes. Nature. 2000;407:102–106. doi: 10.1038/35024111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarcón C., Zaromytidou A.I., Xi Q., Gao S., Yu J., Fujisawa S., Barlas A., Miller A.N., Manova-Todorova K., Macias M.J. Nuclear CDKs drive Smad transcriptional activation and turnover in BMP and TGF-beta pathways. Cell. 2009;139:757–769. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessi F., Quarta S., Savio M., Riva F., Rossi L., Stivala L.A., Scovassi A.I., Meijer L., Prosperi E. The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors olomoucine and roscovitine arrest human fibroblasts in G1 phase by specific inhibition of CDK2 kinase activity. Exp. Cell Res. 1998;245:8–18. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balamotis M.A., Pennella M.A., Stevens J.L., Wasylyk B., Belmont A.S., Berk A.J. Complexity in transcription control at the activation domain-mediator interface. Sci. Signal. 2009;2 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.1164302. ra20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao S.H., Price D.H. Flavopiridol inactivates P-TEFb and blocks most RNA polymerase II transcription in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:31793–31799. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102306200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker T., Kovarik P. Serine phosphorylation of STATs. Oncogene. 2000;19:2628–2637. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dölken L., Ruzsics Z., Rädle B., Friedel C.C., Zimmer R., Mages J., Hoffmann R., Dickinson P., Forster T., Ghazal P., Koszinowski U.H. High-resolution gene expression profiling for simultaneous kinetic parameter analysis of RNA synthesis and decay. RNA. 2008;14:1959–1972. doi: 10.1261/rna.1136108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donner A.J., Ebmeier C.C., Taatjes D.J., Espinosa J.M. CDK8 is a positive regulator of transcriptional elongation within the serum response network. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:194–201. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin J.E., Hackenmiller R., Simon M.C., Levy D.E. Targeted disruption of the mouse Stat1 gene results in compromised innate immunity to viral disease. Cell. 1996;84:443–450. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81289-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebmeier C.C., Taatjes D.J. Activator-Mediator binding regulates Mediator-cofactor interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:11283–11288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914215107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egloff S., Murphy S. Cracking the RNA polymerase II CTD code. Trends Genet. 2008;24:280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmlund H., Baraznenok V., Lindahl M., Samuelsen C.O., Koeck P.J., Holmberg S., Hebert H., Gustafsson C.M. The cyclin-dependent kinase 8 module sterically blocks Mediator interactions with RNA polymerase II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:15788–15793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607483103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firestein R., Bass A.J., Kim S.Y., Dunn I.F., Silver S.J., Guney I., Freed E., Ligon A.H., Vena N., Ogino S. CDK8 is a colorectal cancer oncogene that regulates beta-catenin activity. Nature. 2008;455:547–551. doi: 10.1038/nature07179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedbichler K., Kerenyi M.A., Kovacic B., Li G., Hoelbl A., Yahiaoui S., Sexl V., Müllner E.W., Fajmann S., Cerny-Reiterer S. Stat5a serine 725 and 779 phosphorylation is a prerequisite for hematopoietic transformation. Blood. 2010;116:1548–1558. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-258913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer C.J., White J.B., Jones K.A. Mastermind recruits CycC:CDK8 to phosphorylate the Notch ICD and coordinate activation with turnover. Mol. Cell. 2004;16:509–520. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagey M.H., Newman J.J., Bilodeau S., Zhan Y., Orlando D.A., van Berkum N.L., Ebmeier C.C., Goossens J., Rahl P.B., Levine S.S. Mediator and cohesin connect gene expression and chromatin architecture. Nature. 2010;467:430–435. doi: 10.1038/nature09380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantakamalakul W., Politis A.D., Marecki S., Sullivan T., Ozato K., Fenton M.J., Vogel S.N. Regulation of IFN consensus sequence binding protein expression in murine macrophages. J. Immunol. 1999;162:7417–7425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knuesel M.T., Meyer K.D., Bernecky C., Taatjes D.J. The human CDK8 subcomplex is a molecular switch that controls Mediator coactivator function. Genes Dev. 2009;23:439–451. doi: 10.1101/gad.1767009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knuesel M.T., Meyer K.D., Donner A.J., Espinosa J.M., Taatjes D.J. The human CDK8 subcomplex is a histone kinase that requires Med12 for activity and can function independently of mediator. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009;29:650–661. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00993-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovarik P., Stoiber D., Novy M., Decker T. Stat1 combines signals derived from IFN-gamma and LPS receptors during macrophage activation. EMBO J. 1998;17:3660–3668. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.13.3660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovarik P., Stoiber D., Eyers P.A., Menghini R., Neininger A., Gaestel M., Cohen P., Decker T. Stress-induced phosphorylation of STAT1 at Ser727 requires p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase whereas IFN-gamma uses a different signaling pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:13956–13961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovarik P., Mangold M., Ramsauer K., Heidari H., Steinborn R., Zotter A., Levy D.E., Müller M., Decker T. Specificity of signaling by STAT1 depends on SH2 and C-terminal domains that regulate Ser727 phosphorylation, differentially affecting specific target gene expression. EMBO J. 2001;20:91–100. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubosaki A., Lindgren G., Tagami M., Simon C., Tomaru Y., Miura H., Suzuki T., Arner E., Forrest A.R., Irvine K.M. The combination of gene perturbation assay and ChIP-chip reveals functional direct target genes for IRF8 in THP-1 cells. Mol. Immunol. 2010;47:2295–2302. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.05.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy D.E., Darnell J.E., Jr. Stats: transcriptional control and biological impact. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;3:651–662. doi: 10.1038/nrm909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew D.J., Decker T., Strehlow I., Darnell J.E. Overlapping elements in the guanylate-binding protein gene promoter mediate transcriptional induction by alpha and gamma interferons. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1991;11:182–191. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.1.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W.X. Canonical and non-canonical JAK-STAT signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:545–551. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loncle N., Boube M., Joulia L., Boschiero C., Werner M., Cribbs D.L., Bourbon H.M. Distinct roles for Mediator Cdk8 module subunits in Drosophila development. EMBO J. 2007;26:1045–1054. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMicking J.D. IFN-inducible GTPases and immunity to intracellular pathogens. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:601–609. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMicking J.D., Taylor G.A., McKinney J.D. Immune control of tuberculosis by IFN-gamma-inducible LRG-47. Science. 2003;302:654–659. doi: 10.1126/science.1088063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamane Y., Sharma S., Grandvaux N., Hernandez E., Hiscott J. IRF-4 activities in HTLV-I-induced T cell leukemogenesis. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2002;22:135–143. doi: 10.1089/107999002753452746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K.D., Donner A.J., Knuesel M.T., York A.G., Espinosa J.M., Taatjes D.J. Cooperative activity of cdk8 and GCN5L within Mediator directs tandem phosphoacetylation of histone H3. EMBO J. 2008;27:1447–1457. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K.D., Lin S.C., Bernecky C., Gao Y., Taatjes D.J. p53 activates transcription by directing structural shifts in Mediator. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:753–760. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morinobu A., Gadina M., Strober W., Visconti R., Fornace A., Montagna C., Feldman G.M., Nishikomori R., O’Shea J.J. STAT4 serine phosphorylation is critical for IL-12-induced IFN-gamma production but not for cell proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:12281–12286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182618999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris E.J., Ji J.Y., Yang F., Di Stefano L., Herr A., Moon N.S., Kwon E.J., Haigis K.M., Näär A.M., Dyson N.J. E2F1 represses beta-catenin transcription and is antagonized by both pRB and CDK8. Nature. 2008;455:552–556. doi: 10.1038/nature07310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T.T., Hu Y., Widney D.P., Mar R.A., Smith J.B. Murine GBP-5, a new member of the murine guanylate-binding protein family, is coordinately regulated with other GBPs in vivo and in vitro. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2002;22:899–909. doi: 10.1089/107999002760274926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine R., Canova A., Schindler C. Tyrosine phosphorylated p91 binds to a single element in the ISGF2/IRF-1 promoter to mediate induction by IFN alpha and IFN gamma, and is likely to autoregulate the p91 gene. EMBO J. 1994;13:158–167. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickert P., Corden J.L., Lees E. Cyclin C/CDK8 and cyclin H/CDK7/p36 are biochemically distinct CTD kinases. Oncogene. 1999;18:1093–1102. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadzak I., Schiff M., Gattermeier I., Glinitzer R., Sauer I., Saalmüller A., Yang E., Schaljo B., Kovarik P. Recruitment of Stat1 to chromatin is required for interferon-induced serine phosphorylation of Stat1 transactivation domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:8944–8949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801794105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Schlessinger K., Zhu X., Meffre E., Quimby F., Levy D.E., Darnell J.E., Jr. Essential role of STAT3 in postnatal survival and growth revealed by mice lacking STAT3 serine 727 phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:407–419. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.1.407-419.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strehlow I., Seegert D., Frick C., Bange F.C., Schindler C., Böttger E.C., Decker T. The gene encoding IFP 53/tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase is regulated by the gamma-interferon activation factor. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:16590–16595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taatjes D.J. The human Mediator complex: a versatile, genome-wide regulator of transcription. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2010;35:315–322. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H., Parmely T.J., Sato S., Tomomori-Sato C., Banks C.A., Kong S.E., Szutorisz H., Swanson S.K., Martin-Brown S., Washburn M.P. Human mediator subunit MED26 functions as a docking site for transcription elongation factors. Cell. 2011;146:92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todaro G.J., Green H. Quantitative studies of the growth of mouse embryo cells in culture and their development into established lines. J. Cell Biol. 1963;17:299–313. doi: 10.1083/jcb.17.2.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varinou L., Ramsauer K., Karaghiosoff M., Kolbe T., Pfeffer K., Müller M., Decker T. Phosphorylation of the Stat1 transactivation domain is required for full-fledged IFN-gamma-dependent innate immunity. Immunity. 2003;19:793–802. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00322-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada T., Takagi T., Yamaguchi Y., Watanabe D., Handa H. Evidence that P-TEFb alleviates the negative effect of DSIF on RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription in vitro. EMBO J. 1998;17:7395–7403. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G., Balamotis M.A., Stevens J.L., Yamaguchi Y., Handa H., Berk A.J. Mediator requirement for both recruitment and postrecruitment steps in transcription initiation. Mol. Cell. 2005;17:683–694. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Z., Zhong Z., Darnell J.E., Jr. Maximal activation of transcription by Stat1 and Stat3 requires both tyrosine and serine phosphorylation. Cell. 1995;82:241–250. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerling T., Kuuluvainen E., Mäkelä T.P. Cdk8 is essential for preimplantation mouse development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:6177–6182. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01302-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Huang J., Dasgupta M., Sears N., Miyagi M., Wang B., Chance M.R., Chen X., Du Y., Wang Y. Reversible methylation of promoter-bound STAT3 by histone-modifying enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:21499–21504. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016147107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yankulov K.Y., Bentley D.L. Regulation of CDK7 substrate specificity by MAT1 and TFIIH. EMBO J. 1997;16:1638–1646. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Feng D., Wang Q., Abdulla A., Xie X.J., Zhou J., Sun Y., Yang E.S., Liu L.P., Vaitheesvaran B. Regulation of lipogenesis by cyclin-dependent kinase 8-mediated control of SREBP-1. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:2417–2427. doi: 10.1172/JCI61462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.