Abstract

Background

Although several studies have characterized the hygiene habits of college students, few have assessed the determinants underlying such behaviors.

Objectives

Our study sought to describe students' knowledge, practices, and beliefs about hygiene and determine whether there is an association between reported behaviors and frequency of illness.

Methods

A sample of 299 undergraduate students completed a questionnaire assessing demographics, personal and household hygiene behaviors, beliefs and knowledge about hygiene, and general health status.

Results

Variation in reported hygiene habits was noted across several demographic factors. Women reported “always” washing their hands after using the toilet (87.1%) more than men (65.3%, P = .001). Similarly, freshmen reported such behavior (80.4%) more than sophomores (71.9%), juniors (67.7%), or seniors (50%, P = .011). Whereas 96.6% of participants thought that handwashing was either “very important” or “somewhat important” for preventing disease, smaller proportions thought it could prevent upper respiratory infections (85.1%) or gastroenteritis (48.3%), specifically. There was no significant relationship between reported behaviors and self-reported health status.

Conclusion

The hygiene habits of college students may be motivated by perceptions of socially acceptable behavior rather than scientific knowledge. Interventions targeting the social norms of incoming and continuing students may be effective in improving hygiene determinants and ultimately hygiene practices.

Keywords: Health behaviors, Handwasing, Student health

A causal link between hand hygiene and rates of infectious illness has been established in the literature.1,2 A recent meta-analysis of 30 hand hygiene studies found that improvements in handwashing reduced the incidence of upper respiratory tract infections by 21% and gastrointestinal illnesses by 31%.3 Poor adherence to hand hygiene practices has been described among students in the university setting.4,5 Deficiencies in hand hygiene have been associated with outbreaks of viral gastroenteritis,6 upper respiratory tract infections,7,8 and group B streptococcal colonization9 in this setting. Given this relationship between personal hygiene and health, we hypothesize that the knowledge and beliefs underlying a student's hygiene practices may be important determinants of his or her health. Although the morbidity and mortality associated with viral respiratory and gastrointestinal illnesses among college students are relatively low, these infections contribute to absenteeism that may, in turn, affect academic productivity and performance.10 Furthermore, such illnesses may strain student health services during outbreaks and may contribute to inappropriate use of antibacterial agents.

Whereas several studies have addressed the hand hygiene practices of college students, few have described the students' knowledge and beliefs surrounding these practices.4–8,11 Such factors are likely shaped by a variety of determinants including the practices modeled by family members and peers, as well as those portrayed in the media and educational system. These practices may also vary according to individual experience and interests. Previous research has demonstrated more frequent hand hygiene among women compared with men and science majors compared with non-science majors.4 It is unclear whether such variations arise out of differing beliefs about hand hygiene itself or out of differing tendencies to practice socially acceptable behavior. The aims of this study were to (1) describe the knowledge, practices, and beliefs about personal and home hygiene held by college students and (2) determine whether there is an association between reported hygiene habits and the frequency of illness. A more comprehensive understanding of hygiene determinants among college students may improve our ability to design and implement effective hygiene interventions in the university setting.

METHODS

Sample and setting

We performed a cross-sectional survey of hygiene beliefs, attitudes, and practices among undergraduate students at Columbia University in New York City. During the spring 2011 semester, study participants were recruited at the John Jay dining hall, the larger of 2 dining facilities serving undergraduates. All students presenting to the dining hall were eligible to participate in the study. Columbia University freshmen are required to purchase a university-sponsored meal plan and therefore utilize the dining hall on a regular basis. As such, the sample of first-year students included in the study mimics the larger freshman population. Smaller numbers of upper-year students participate in the meal plan and are consequently less represented among dining hall patrons. Upper class students with individualized eating habits (raw vegans, Hilal students, and those with severe food allergies) may be more likely to opt out of the voluntary meal plan and are potentially less represented in our study. Because 95% of Columbia undergraduates live in student housing, our sample has strong external validity to the larger undergraduate population at the university. This research was conducted with the collaboration of Columbia University Student Health Services, Housing Services, and Dining Services. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University Medical Center.

Questionnaire

The survey instrument, which required approximately 10 minutes to complete, included 60 questions that were a combination of multiple choice, Likert scale, and open-ended items. Questions were grouped broadly into 5 categories: (1) student demographics and living situation (age, gender, school year, academic concentration, number of roommates/suitemates, and dormitory style, ie, traditional hall vs suite), (2) personal hygiene (frequency of handwashing and bathing, personal hygiene practices, and types of products used including alcohol-based sanitizers), (3) household hygiene (frequency of household cleaning, and persons responsible for household cleaning), (4) beliefs and knowledge about hygiene (perception of infection risk, ranking of own hygienic practices relative to others, beliefs about the efficacy of personal and household hygiene, and sources of infection control information), and (5) general health status (chronic conditions, symptoms of illness, school days missed, medical care sought, and antibiotics taken in the past month). To protect subject privacy, no personal identifying information was collected. As such, verification of self-reported health status with data from student health services was not possible. Previous research has found self-reported health status to be an acceptable proxy for observed medical measures in select populations.12 Survey questions were adapted from a previously validated hygiene measure.13 The questionnaire was pretested on Columbia University graduate students (N = 10) for clarity and validity. Based on this feedback, select questions were edited or eliminated.

Data collection

Members of the research team were stationed at the entrance to the university's main dining hall over weeknight dinnertimes in the spring 2011 semester. Upon entering the dining hall, students were notified of the study. Any student interested in learning about the research aims and methods was provided with information about the study. Prospective participants were asked to provide verbal consent prior to initiation of the questionnaire. Study subjects were then asked to complete the survey while present in the dining hall. Participants were compensated $10 for their time. All data were collected in an anonymous fashion, and no information linked an individual's questionnaire to his or her identity.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with SPSS software (PASW Statistics 18.0; IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY). Categorical data from multiple choice questions were analyzed using χ2 or Fisher's exact test. Statistical significance was defined as α less than or equal to .05. For evaluation of overall personal hygiene, a composite score was created from answers to 6 questions regarding opportunities for hand hygiene. In these questions, participants were asked how often they washed their hands in specific scenarios and were awarded a point for responding “always.” All other answer choices, ranging from “most of the time” to “never,” were given 0 points. The composite personal hygiene score ranged from 0 to 6 with higher values representing more frequent hand hygiene. Similarly, a composite household hygiene score was created from 7 questions pertaining to the cleaning of various dormitory room surfaces. Responses were scored 0 for “never,” 1 for “once per year,” 2 for “once per semester,” 3 for “once per month,” and 4 for “once per week.” The household hygiene composite score ranged from 0 to 28, with higher scores reflecting more frequent household cleaning. See Table 1 for questions that comprised the personal and household hygiene composite scores. Correlation between the composite personal hygiene score and the composite household hygiene score was calculated with a linear regression analysis.

Table 1.

Items included in composite scores

| Mean scores (range) | |

|---|---|

| Personal hygiene composite score | |

| 1. Upon getting home, do you wash your hands? | 0.15 (0–1) |

| 2. Upon finishing a workout at a gym facility, do you wash your hands? | 0.33 (0–1) |

| 3. After touching a pet or other animal, do you wash your hands? | 0.25 (0–1) |

| 4. Before eating, do you wash your hands? | 0.14 (0–1) |

| 5. Before preparing food, do you wash your hands? | 0.65 (0–1) |

| 6. After using the toilet, do you wash your hands? | 0.75 (0–1) |

| Total personal hygiene composite score | 2.27 (0–6) |

| Household hygiene composite score | |

| 1. How often is your computer keyboard cleaned by you or someone else? | 1.42 (0–4) |

| 2. How often are your bookshelves/storage bins cleaned by you or someone else? | 1.44 (0–4) |

| 3. How often is your desk surface cleaned by you or someone else? | 2.34 (0–4) |

| 4. How often is your television remote control cleaned by you or someone else? | 0.81 (0–4) |

| 5. How often is your overhead light switch cleaned by you or someone else? | 0.77 (0–4) |

| 6. How often is your dish/cup/mug cleaned by you or someone else? | 3.35 (0–4) |

| 7. How often is your refrigerator handle cleaned by you or someone else? | 1.09 (0–4) |

| Total household hygiene composite score | 11.22(0–28) |

NOTE. The personal hygiene composite score was created from answers to 6 questions regarding opportunities for hand hygiene. Participants were given 1 point for responding that they “lways” wash their hands in a particular setting. The summation of the points ranged from 0 to 6, with higher values representing more frequent hand hygiene. The composite household hygiene score was created from 7 questions pertaining to the cleaning of various dormitory room surfaces. Responses were scored 0 for “never,”1 for “once per year,” 2 for “once per semester,” 3 for “once per month,” and 4 for “once per week.” Similarly, the sum of points ranged from 0 to 28, with higher scores representing more frequent home hygiene.

Individual questions on health status were used to create a composite binary health score. Students who reported symptoms (upper respiratory complaints, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea) missed classes because of illness, physician visits, or antibiotic use for 3 or more days in the preceding month were given a health score of 0. Students who did not experience these events or experienced them for 2 or fewer days in the preceding month were given a health score of 1. To assess the relationship between reported behaviors and health status, correlations between the composite personal and household hygiene scores with the binary health score were calculated with a logistic regression analysis.

RESULTS

Demographics

A total of 299 students completed the study survey. Mean age was 19.2 years (range, 17–28), with 60.1% of participants in their first year of college. Demographic factors mirrored the larger student body, with 55% men and a wide distribution of academic interests (44% science majors, 36% humanities majors, 18% undecided). According to study design, all participants lived in university housing. Living environment varied by style of housing (59.1% in hall-style dormitories, 40.9% in suite-style dormitories) and number of roommates (51.3% in single rooms, 48.7% in doubles or more). Of study participants, 95.6% described their health as “excellent” or “good,” and 81.6% reported no chronic medical conditions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographics of study participants

| Demographic variable | Number (percentage) |

|---|---|

| Age, yr | Mean, 19.2; range, 17–28 |

| Gender | 167 (55.9) Men |

| 132 (44.1) Women | |

| Academic concentration | 132 (44.6) Science majors |

| 108 (36.5) Humanities majors | |

| 54 (18.2) Undecided | |

| 2 (0.7) Double major | |

| Class year | 179 (59.9) Freshmen |

| 64 (21.4) Sophomores | |

| 31 (10.4) Juniors | |

| 24 (8) Seniors | |

| Dormitory style | 176 (59.1) Hall |

| 122 (40.9) Suite | |

| Room style | 153 (51.3) Single |

| 145 (48.7) Double (or more) | |

| Reported health status | 285 (95.6) Excellent or good |

| 13 (4.4) Fair or poor | |

| Reported medical history | 244 (81.6) No medical history |

| 55 (18.4) One or more medical issues |

Personal hygiene

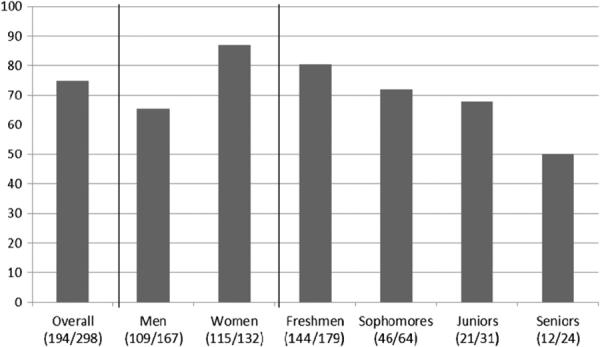

Nearly half of all study participants (47.5%) reported that they washed their hands at least 5 times per day. This observation varied by gender, with women reporting greater frequency of hand hygiene compared with men (55.3% of women wash ≥5 times/day vs 41.3% of men, P =.012). The most commonly utilized product for hand hygiene was liquid soap (83.3% of respondents), although use of alcohol-based hand sanitizer was noted by nearly half (49.5%) of study subjects. Duration of handwashing showed variability, with 49% of respondents reporting less than 15 seconds per wash, 41.6% reporting 15 to 29 seconds per wash, and 9.4% reporting greater than 30 seconds per wash; 74.9% of study participants reported that they “always” wash their hands after using the toilet, with smaller proportions reporting “most of the time” (17.4%) and “sometimes” (7.7%). This observation varied on several demographic factors. Women reported “always” (87.1%) more than men (65.3%, P =.001). Science and humanities majors reported “always” (78% and 75%, respectively) more than undecided students (66.7%, P = .047). Furthermore, freshmen reported “always” (80.4%) more than sophomores (71.9%), juniors (67.7%), and seniors (50%, P = .011, Fig 1). The majority of respondents reported daily showers (65.7%) and twice daily tooth brushing (65.2%). Students living in suite-style residences reported “greater than once daily showering” (20.7%) more than students living in traditional hall-style residences (8.0%, P = .01). A minority of students reported sharing personal hygiene products with others (17.1% hand towel, 7.7% bath towel, 10.0% bar soap, 5.4% hairbrush, 2.0% toothbrush).

Fig 1.

Percentage of study subjects who report “always” washing their hands after using the toilet. Women reported “always” washing their hands after using the toilet (87.1%) more than men (65.3%, P = .001). Furthermore, freshmen reported “always” (80.4%) more than sophomores (71.9%), juniors (67.7%), and seniors (50%, P = .011).

The mean composite personal hygiene score for study participants was 2.27 with a range of 0 to 6. The individual components of this score, with average values, are listed in Table 1. Whereas men had a lower mean composite personal hygiene score (2.15) compared with women (2.44), this did not reach statistical significance (P = .12). Humanities majors had a lower mean score (2.02) than science majors (2.58, P = .008).

Household hygiene

Frequency of dorm room cleaning was markedly variable. Whereas 52.7% of students reported that their room was cleaned once per week, responses ranged from once per day (12.2%) to never (11.8%). There were no aggregate changes in cleaning habits when study respondents were ill (29% clean more often, 29.6% clean less often, 41.4% clean about the same), although many (40.9%) increased the frequency of cleaning when their roommate was sick. Disinfecting cleaners (vs nondisinfecting cleaners such as water, and others) were the most commonly reported products used by students for environmental cleaning. The mean composite household hygiene score for study participants was 11.22, with a range of 0 to 28. Table 1 shows the components of this score with the mean values for each element. Although the mean composite household hygiene score for men (10.1) was lower than for women (12.5, P =.006), there were no significant differences based on other demographic factors. The personal hygiene composite score correlated slightly with the household hygiene composite score in a liner regression model (parameter estimate, 1.614; r2 = 0.135; P ≤ .001).

Beliefs and knowledge

Most study participants reported that their personal hygiene was the same (57.4%) or better (38.9%) than their peers. Similarly, the majority believed their household hygiene was the same (54.4%) or better (31.9%) than others. These answer choices did not vary significantly by gender or other demographic factors. Nearly all students thought that hand hygiene was either “very important” (79.2%) or “somewhat important” (17.4%) in preventing disease. Disinfecting the living environment was seen as “very important” by 59.0% of respondents, “somewhat important” by 32.9% of respondents, and “unimportant” by 8.1% of respondents. Each of these responses varied by gender with 71.9% of men defining hand hygiene as “very important” compared with 88.5% of women (P = .001). Similarly, 44.8% of men characterized household disinfecting as “very important” compared with 55.2% of women (P ≤ .001). The importance of household disinfection also varied by class and residence type, with freshmen living in hall-style dormitories placing the greatest importance on disinfecting. Whereas 85.1% of study participants thought that handwashing could prevent the transmission of a cold or flu, only 48.3% felt that it could prevent the transmission of gastroenteritis. The specific sources of infection prevention knowledge (ie, formal teaching, television, new media, and others) were not assessed by this study. Of note, 59.9% of study participants considered university-produced health bulletins as a potential resource for medical information.

Health status

There was variability in the reported health status of participants. Although 17.5% of study participants reported illness for 1 or more weeks of the past month, only 27.2% noted no days of sickness. The majority of students (52.4%) reported between 1 and 6 days of illness. A subset of students (17.0 %) reported missed classes because of sickness with a cold, flu, or gastroenteritis. A similar number (16.4%) took antibiotics over the past month. 38.4% of participants reported no or minimal illness-related events over the past month and received a binary composite health score of 1; 61.6% reported at least 3 days of one or more health-related events (symptoms, missed class, health care visits, or antibacterial treatment) and received a score of 0. The personal hygiene composite score was not associated with the binary health status score in logistic regression analysis (odds ratio, 1.07, P = .33). Similarly, the household hygiene composite score did not show an association with the binary health status score in logistic regression analysis (odds ratio, 1.015; P = .33).

DISCUSSION

Because dormitories often reproduce many factors conducive to bacterial and viral transmission (close contact with numerous individuals, shared living spaces, variable hygiene habits of residents), college students are at particularly high risk for infectious diseases.4–11 Prior studies have shown that improved hygiene—particularly hand hygiene—provides a simple and cost-effective means for preventing the spread of infection in this population.1–3 Despite this, substantial evidence has shown that handwashing behavior is poor even when soap and water are available.14,15 If novel strategies are to be designed to improve adherence to safe hygiene practices, an understanding of the psychological and environmental factors underlying these behaviors is essential. Whereas several studies have evaluated the hygiene habits of college students in various settings, few have examined the psychological and social factors underlying such behaviors. Our study contributes to the understanding of these determinants by evaluating the hygiene-related beliefs and knowledge held by college students. Although our findings reinforce certain previously recognized epidemiologic determinants of reported hygiene, we also suggest novel risk factors for deficient hygiene behavior, illuminating certain subpopulations of college students who may benefit from targeted health education. Furthermore, our exploration of beliefs and knowledge surrounding reported hygiene behaviors may facilitate hypothesis-driven intervention strategies in the college setting.

Certain personal hygiene behaviors appeared to be universally strong among study participants, with the vast majority of respondents stating that they wash their hands “always” or “most of the time” after using the toilet. Despite this, other behaviors (ie, handwashing prior to eating a meal or after touching an animal) were rarely reported by study subjects. Such variability is evident in the components of the personal hygiene composite score as listed in Table 1. The heterogeneity of the individual behaviors comprising our metric potentially highlights the diverse understandings of “personal hygiene” held by study participants. Although the personal hygiene composite score reflects medically accepted opportunities for hand hygiene, individual study participants may not consider all elements as important health behaviors.

Consistent with previous research, women noted better personal hygiene than men.4 Interestingly, college freshmen reported better hygiene than sophomores, juniors, or seniors, suggesting a possible deterioration in personal hygiene over the college years. The accuracy of these responses relative to actual hygiene behavior being performed is uncertain because questionnaire data have been shown to overestimate handwashing, often by a factor of 2 to 3 times.15 Still, the results provide interesting insight into the behaviors that college students believe to be “morally” or “scientifically” correct or socially desirable. Indeed, the reported personal hygiene behaviors of study subjects were congruent with their underlying beliefs, with 96.6% of students surveyed stating that handwashing was either “very important” or “somewhat important” in preventing disease. Similar to their reported behavior, women and underclassmen defined handwashing as “very important” more often than men and upperclassmen, respectively. Interestingly, the knowledge informing such beliefs was variable. Whereas 85.1% of study participants were convinced that hand-washing could prevent the transmission of a cold or flu, only 48.3% believed it could prevent the transmission of gastroenteritis (nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea). Taken together, these data suggest that many college students “believe” that handwashing is important without being fully cognizant of the scientific reasons for its application.

Based on a review of 11 studies conducted in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, Curtis et al have put forth a characterization of hygiene behavior into 3 categories: habitual, motivated, and planned.16 Habitual hygiene relates to behaviors learned in early childhood, often through modeling and reinforcement by the primary caregiver. Motivational determinants include disgust over contamination, the wish to fulfill a social norm, the desire to care for one's child, or fear of an infectious threat. Planned hygiene, relating to the belief that handwashing can promote long-term health, is the least common behavior observed. Because habitual hygiene behaviors are learned well before adulthood, they are unlikely to be useful targets for improving handwashing among college students. Both motivated and planned hygiene activities do provide opportunities for intervention in the dormitory setting. The deterioration of reported personal hygiene over the 4 years of college suggests that underclassmen may wish to participate—or be perceived to be participating—in socially normative behaviors more than their upper-class counterparts. Given the incongruence between underlying knowledge of handwashing mechanisms and commonly held hand hygiene beliefs, it is less likely that “planned” hygiene is a substantial component of the behavior being reported in our study. Our data suggest that campaigns aimed at (1) establishing and sustaining social norms of good personal hygiene and (2) educating students on the biologic mechanisms by which handwashing prevents disease could be most useful to increase safe hygiene practices.

Household hygiene, as reflected by the frequency of cleaning various dormitory surfaces, showed significant variability in our study. Environmental cleaning frequencies ranged from “once per day” to “never,” with average values shown in Table 1. As with the personal hygiene measures noted above, men reported worse household hygiene habits compared with women. The underlying beliefs surrounding household hygiene were similarly congruent with reported behaviors; 59% of study subjects thought that disinfecting the living environment was “very important,” 20% less than those who place such importance on handwashing. Interestingly, a significant proportion of participants (40.9%) stated that they clean their room more frequently when their roommate is sick, suggesting “motivated” or “planned” behavior with the intent of reducing transmission of infection or improving health. Similar to personal hygiene, freshmen placed more importance on disinfecting the living environment to prevent disease compared with sophomores, juniors, or seniors. Again, this may relate to “motivated” behavior aimed at achieving social norms.

Our study failed to show an association between reported hygiene behaviors and health outcomes. Because previous evidence has shown a conclusive relationship between hand hygiene and decreased incidence of upper respiratory infections and gastroenteritis, our negative finding likely relates to study design limitations.1–3,15 It is possible that our sample size was not sufficiently powered to detect a difference in health outcomes based on the limited variability in hand hygiene behavior reported. More likely, our lack of correlation between hygiene and health relates to the imprecision of questionnaire data in predicting actual hygiene habits. As noted above, numerous studies have shown that self-reported data substantially overestimate true hygiene habits.15,16 It is likely that our data suffer from similar reporting biases that undermine their ability to truly reflect the actual behavior of study participants. This inability to accurately categorize true behavior consequently impairs our ability to demonstrate a significant relationship between personal or household hygiene and health status. However, the apparent congruence between underlying beliefs and self-reported hygiene habits allows for determination of specific demographic factors associated with the “motivation” to attain safe hygiene behaviors. Students who show a desire to fulfill particular social expectations of personal and household hygiene are likely to be most responsive to a norms-based message. Based on our data, interventions targeting the social norms of incoming students may be effective in improving hygiene motivation and ultimately hygiene practices. Similarly, efforts to cultivate social expectations of safe hygiene in the residence halls of upperclassmen may prove effective as well.

University students represent a population uniquely situated to benefit from hygiene interventions. As college students transition into independent adulthood, they are likely to develop a foundation of personal behaviors that may persist for decades to come. Considering their elevated risk of infection, this population is an important target for novel strategies aimed at promoting safe hygiene practices. Although several studies have addressed this issue, few have considered the psychological determinants of such behavioral change. Through attaining an understanding of the beliefs and knowledge underlying the hygiene habits of college students, we will be better suited to develop fresh approaches to this important public health problem.

Acknowledgments

Supported by “Training in Interdisciplinary Research to Reduce Antimicrobial Resistance (TIRAR),” NIH T90 NR010824 at Columbia University School of Nursing, and by The Clorox Company.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None to report.

References

- 1.Aiello AE, Larson EL. What is the evidence for a causal link between hygiene and infection? Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:103–10. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00184-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiello AE, Larson EL. Causal inference: the case of hygiene and health. Am J Infect Control. 2002;60:503–10. doi: 10.1067/mic.2002.124585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aiello AE, Coulborn RM, Perez V, Larson EL. Effect of hand hygiene on infectious disease risk in the community setting: a meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1372–81. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.124610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson JL, Warren CL, Perez E, Louis RI, Phillips S, Wheeler J, et al. Gender and ethnic differences in hand hygiene practices among college students. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36:361–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Surgeoner BV, Chapman BJ, Powell DA. University students' hand hygiene practice during a gastrointestinal outbreak in residence: what they say they do and what they actually do. J Environ Health. 2009;72:24–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moe CL, Christmas WA, Echols LJ, Miller SE. Outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis associated with Norwalk-like virus in campus setting. J Am Coll Health. 2001;50:57–66. doi: 10.1080/07448480109596008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White C, Kolble R, Carlson R, Lipson N. The impact of a health campaign on hand hygiene and upper respiratory illness among college students living in residence halls. J Am Coll Health. 2005;53:175–81. doi: 10.3200/JACH.53.4.175-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White C, Kolble R, Carlson R, Lipson N, Dolan M, Ali Y, et al. The effect of hand hygiene on illness rates among students in university residence halls. Am J Infect Control. 2003;31:364–70. doi: 10.1016/s0196-6553(03)00041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bliss SJ, Manning SD, Tallman P, Baker CJ, Paerlman MD, Marrs CF, et al. Group B Streptococcus colonization in male and nonpregnant female university students: a cross-sectional prevalence study. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:184–90. doi: 10.1086/338258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American College Health Association . American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment II: Reference Group Executive Summary fall 2010. American College Health Association; Linthicum [MD]: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor JK, Basco R, Zaied A, Ward C. Hand hygiene knowledge of college students. Clin Lab Sci. 2010;23:89–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miilunpalo S, Vuori L, Pekka O, Pasanen M, Urponen H. Self-rated health status as a health measure: the predictive value of self-reported health status on the use of physician services and on mortality in the working-age population. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:517–28. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stevenson RJ, Case TI, Hodgson D, Porzig-Drummond R, Barouei J, Oaten MJ. A scale for measuring hygiene behavior: development, reliability and validity. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37:557–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Judah G, Aunger R, Schmidt WP, Michie S, Granger S, Cutris V. Experimental pretesting of hand-washing interventions in a natural setting. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:S405–11. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.164160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curtis V, Schmidt W, Luby S, Florez R, Touré O, Biran A. Hygiene: new hopes, new horizons. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:312–21. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70224-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curtis V, Danquah L, Aunger R. Planned, motivated, and habitual hygiene behavior: an eleven country review. Health Ed Res. 2009;24:655–73. doi: 10.1093/her/cyp002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]