Abstract

Carrying objects requires coordination of manual action and locomotion. This study investigated spontaneous carrying in 24 13-month-old walkers and 26 13-month-old crawlers during 1-hour, naturalistic observations in infants’ homes. Carrying was more common in walkers, but crawlers also carried objects. Typically, walkers carried objects in their hands whereas crawlers multitasked by using their hands simultaneously for holding objects and supporting their bodies. Locomotor experience predicted frequency of carrying in both groups, suggesting that experienced crawlers and walkers perceive their increased abilities to handle objects while in motion. Despite additional biomechanical constraints imposed by holding an object, carrying may actually improve upright balance: Crawlers rarely fell while carrying an object and walkers were more likely to fall without an object in hand than while carrying. Thus, without incurring additional risk of falling, spontaneous carrying may provide infants with new avenues for combining locomotor and manual skills and for interacting with their environments.

Keywords: infant locomotion, object exploration, load carriage

For nearly 100 years, researchers have studied infants’ acquisition of manual and locomotor skills. The literature is replete with descriptions of infant reaching, grasping, and object manipulation, and the development of crawling and walking (Adolph & Berger, 2006; Bertenthal & Clifton, 1998). Despite rich descriptive work on the separate developmental progressions of infants’ manual and locomotor skills, researchers know surprisingly little about how manual and locomotor skills are combined. This study focused on carrying objects, a skill that involves the coordination of manual actions and locomotion.

Carrying Objects in Crawling, Cruising, and Walking Postures

Developmental changes in locomotion pose unique opportunities and challenges for carrying objects. By the time infants begin walking, they have acquired several months of practice reaching, grasping, and manipulating objects (Adolph & Berger, 2006; Bertenthal & Clifton, 1998). Motivation to transport objects is presumably high. Toddlers frequently carry objects to share them with their caregivers (Karasik, Tamis-LeMonda, & Adolph, in press) and researchers routinely encourage infants to carry small objects to elicit walking from one point to another (e.g., Schmuckler & Gibson, 1989). But what about carrying before infants can walk or in the first weeks after walking onset when infants can barely keep balance?

Traditionally, researchers have considered object transport in terms of the availability of the hands, meaning that carrying should emerge after walking onset when hands are no longer required for supporting the body during locomotion. Infants’ first success at mobility is likely to be crawling or cruising (Adolph, Berger, & Leo, in press) where the hands are engaged in locomotion, making object transport a challenge. In a crawling posture, the hands are occupied with supporting the body and propelling it forward. Similarly, when infants hoist themselves into an upright “cruising” posture, the hands and arms serve supporting functions—to hang onto the edge of the coffee table or couch for support. Only after infants can take independent walking steps are the hands freed from supporting the body, providing new opportunities to use the hands for carrying objects. Indeed, many anthropologists consider object transport as a fortuitous byproduct of the evolution of bipedalism (Videan & McGrew, 2002) and some even argue that carrying was a selective impetus in the evolution of walking (Hewes, 1961; reviewed in Stanford, 2003).

During the development of locomotion, the benefits of using the hands for object transport compete with the exigencies of maintaining balance. The development of walking poses new challenges for carrying objects. Although infants’ hands are no longer needed for supporting the body, their arms may be required to keep balance: Newly walking infants hold their arms rigidly in a high-guard position like tight rope walkers (Kubo & Ulrich, 2006; Ledebt, 2000; McGraw, 1945). Because balance is shaky, infants’ gait is notoriously clumsy and falls are commonplace (Adolph, Komati, Garciaguirre, Badaly, & Sotsky, 2011; Adolph, Vereijken, & Shrout, 2003). Carrying objects may exacerbate new walkers’ already precarious balance by adding mass to the body and displacing the location of the center of gravity (Garciaguirre, Adolph, & Shrout, 2007; Vereijken, Pedersen, & Storksen, 2009). Thus, transporting objects while crawling and cruising may be easier than in early stages of walking. In crawling and cruising postures, infants’ weight is distributed over four rather than two limbs, making balance steadier, and infants may be better able to adjust their movements to accommodate an object in hand. Moreover, during the same period when infants crawl and cruise, they also locomote with a variety of hitching movements in a sitting position (Robson, 1984; Trettien, 1900), thereby freeing up the hands for carrying objects.

Load Carriage versus Carrying Objects

Previous work with infants has focused on load carriage, not object carrying. Rather than observing whether and how infants coordinate locomotion with carrying objects in their hands, load carriage was imposed by adding mass to infants’ bodies. Researchers strapped lead-weighted packs to infants’ shoulders, waists, or ankles and then encouraged them to walk repeatedly along the same path so as to observe changes in their posture and gait (Adolph & Avolio, 2000; Garciaguirre, et al., 2007; Schmuckler, 1993; Vereijken, et al., 2009). Previous work did not examine infants’ spontaneous selection of objects for transport during the course of everyday play.

Nonetheless, findings from load carriage studies raise several intriguing speculations about infants’ spontaneous transport of objects. First, imposed load carriage disrupts infant walking. Gait patterns while loaded are more immature than when infants are not loaded and infants are more likely to misstep and fall (Garciaguirre, et al., 2007; Vereijken, et al., 2009). In fact, while carrying 15% of their body weight in shoulder packs, infants exhibited a four-fold increase in gait disruptions compared with feather-weight packs. Second, walking experience helps infants to cope with imposed loads. Less experienced walkers are more disrupted by imposed loads than more experienced walkers (Garciaguirre, et al., 2007; Vereijken, et al., 2009). Thus, newly walking infants may fall more during self-initiated object carrying and may be more reticent to carry objects than more experienced walkers. Third, asymmetrical loads to the front, side, or back of the body are more challenging than symmetrical loads distributed evenly around the body (Garciaguirre, et al., 2007). Unlike adults, infants do not compensate for asymmetrical loads by leaning in the direction opposite to the load. Thus, spontaneous object carrying may be especially challenging because it primarily involves asymmetrical loads—typically carrying objects in both hands to the front of the body or in one hand to the side of the body.

A final intriguing finding is that infants show prospective awareness of their altered abilities during imposed load carriage. New walkers sometimes refuse to move with loads strapped to their bodies, but experienced walkers carry their loads back and forth on dozens of trials (Vereijken, et al., 2009). By 14 months of age, infants perceive that imposed loads diminish their ability to keep balance while walking down slopes and they correctly treat the same degree of slope as risky while loaded with 25% of their body weight but as safe when their shoulder packs are filled with feather-weight polyfill (Adolph & Avolio, 2000). Thus, during everyday play, infants may be aware that carrying an object alters the biomechanics of gait and changes the affordances for locomotion; accordingly, they may select objects to carry that are least likely to disrupt their gait. Indeed, when experimenters offered infants various objects to carry, they were less likely to walk if the object was large or heavy (Bushnell, Baxter, Fitzgerald, & Clearfield, 2009).

Unfortunately, previous work on imposed load carriage is missing some of the most important psychological functions and developmental challenges of carrying objects. In everyday life, infants must select an appropriate object for transport from the array of objects naturally available to them by recognizing the relevant object properties—size, weight, and number of objects. Second, they must determine a destination and purpose of transport, even if goals change mid-route. Finally, to move while holding an object in their hands, they must modify their locomotor and manual actions to accomplish the carrying task successfully without dropping the object or falling. In previous studies of imposed load carriage, infants had no choice about what objects to carry, loads were uniform, and experimenters determined the destination (typically, the end of a walkway). Because previous work focused exclusively on walking infants in laboratory settings, we do not know whether or how infants carry objects in a crawling or cruising posture during their everyday activities at home.

Current Study

The current study addresses some of the gaps of the previous work. We observed infants in their homes during normal everyday routines. Carrying was spontaneous not imposed. We tested 13-month-olds to capitalize on individual differences in infants’ locomotor posture and experience. By 13 months of age, some infants have begun walking, but others are still crawling. While holding age constant, we asked whether infants’ locomotor status (crawler or walker) and locomotor experience (days of crawling and walking) were related to the frequency and quality of spontaneous carrying.

In contrast to previous studies of imposed load carriage, infants chose what to carry, how to coordinate manual and locomotor actions so as to minimize mishaps, and the destination of the transport. We assessed infants’ object selection in terms of the type, size, and quantity of objects. We examined manual-locomotor coordination in terms of infants’ position while carrying (walking, crawling, cruising, hitching in a sitting position, and holding mother’s hand for support), whether objects were carried in the hands, arms, mouth, or pushed along the floor, and whether objects were distributed symmetrically (in both hands to each side of the body) or asymmetrically (in one hand to the front or side of the body or both hands to the front of the body). We coded the outcome of the carrying bouts based on whether infants dropped the object or fell. We assessed the destination in terms of carrying objects to mothers, bringing the carried object to another object, and stopping to explore the surroundings or play with the object in hand.

If using the hands to support the body precludes object transport, then carrying should be rare in a crawling posture. If hands are required to maintain balance in early stages of walking, then carrying should increase over weeks of walking experience. Based on previous studies of imposed load carriage, we expected that infants would select small objects and distribute them symmetrically by carrying an object in each hand. Falls should be more frequent while carrying than not and in the least experienced infants. Previous work on object sharing suggests that walkers should choose mothers as a destination more frequently than crawlers (Karasik, et al., in press).

Method

Participants and Procedure

Fifty 13-month-old (SD = 0.25 months) healthy, term infants participated. Families were recruited from the greater New York City metropolitan area via purchased mailing lists, brochures, referrals, and parenting websites. Most infants were white (74%) and from middle-class families. To obtain a basic description of infants’ home environments, an experimenter walked through each residence while panning a video camera. Homes ranged from 3 to 13 rooms (M = 4.8 rooms); 40 lived in single-floor apartments, 8 in houses with stairs, and 2 lived in large lofts. Twelve infants had siblings. Twenty-four infants had toy chests. Infant toys were visible in 54% of the rooms in infants’ homes. Families received photo albums of their infants as souvenirs for participation.

Twenty-six infants (12 girls, 14 boys) were crawlers and 24 (12 girls, 12 boys) were walkers. Twenty-five crawlers moved on hands and knees and one hitched on his bottom. None could walk 3 m independently, but 11 could take 1–3 independent walking steps and 24 could cruise. Infants crawled or walked over a 16-foot mat to verify their locomotor status. During daily activities, all of the walkers frequently reverted to crawling.

Mothers reported infants’ locomotor experience in the context of a structured interview (Adolph, et al., 2003). They reported the first day that they witnessed infants crawling on hands-and-knees (3 m, typically the length of a room or hallway), cruising along furniture (1.5 m, the length of a couch), and walking independently (3 m), consulting baby books and calendars to aid their memory. Locomotor experience was calculated as the number of days between onset and test date.

Most crawlers were experienced at crawling (M = 3.90 months, range = 2.54 –5.75 months) and most walkers were novices at walking (M = 1.00 month, range = 2 days – 2.01 months). Crawlers had 4 times more crawling experience than walkers had walking experience, t(48) = 12.66, p < .05. However, crawlers and walkers had equivalent amounts of crawling experience, (M = 3.89 and 3.54, SD = 1.00 and 1.00, respectively, p > .05). Boys and girls began crawling and walking at similar ages and had equivalent amounts of crawling and walking experience (all ps > .05). The infant who hitched in a sitting position never crawled or cruised and his experience data were not considered in the relevant analyses. Experience data from a second crawler were unavailable.

Infants were videotaped for 1 hour in their homes at a time when they were not napping or being fed a meal. During taping, the experimenter remained in the background and offered minimal responses to infants and mothers. Mothers were told to go about their normal daily routines and were not told that the focus of the study was on objects or carrying. Objects were those normally available in the home.

Data Coding

Behavioral data were scored from video files using a computerized video coding system, OpenSHAPA (www.OpenSHAPA.org) that records the frequencies and durations of specific behaviors (Sanderson, et al., 1994). A primary coder scored every variable. A second coder scored 33%–50% of the data to ensure inter-rater reliability. Inter-rater reliability ranged from 91.4%–99.4% (all κ values p < .001). Correlations for continuous variables were r = .96–.98, p < .001. Disagreements between coders were resolved through discussion.

The primary coder scored the frequency and duration of carrying bouts—moving forward while holding an object. A conservative criterion was used to eliminate steps in place: Coders only scored bouts with at least 4 consecutive forward steps (separated by < 0.5 s with limbs on the floor at rest). Steps were defined in terms of forward leg movements for crawling, cruising, and walking. For hitching in a sitting position, each forward scoot counted as a step. Duration of carrying began with the first frame infants moved forward and ended when they stopped moving (paused in place for ≥ .5 s), dropped the object, or fell. The criterion for scoring a pause was derived from the literature on infant walking: double support phases in continuous walking are < 0.5 s (e.g., Bril & Breniere, 1989; Garciaguirre, et al., 2007), meaning that longer pauses are actual disruptions in continuous walking.

To assess object characteristics, the coder scored object type (toys, books, food, and household objects such as kitchen gadgets, office supplies, and remote controls) and object size (estimated relative to infants’ body). Small objects were the size of infants’ hand or smaller; medium objects were larger than infants’ hand but smaller than their heads; and large objects were at least the size of infants’ heads. We scored object number (1, 2, etc.), hand use (one hand or both hands), and object position (front or side of body) to obtain a crude index of load distribution: symmetrical carrying with an object in each hand to the sides of the body and asymmetrical carrying using one hand to carry a single object to the side or front of the body or two hands carrying one or two objects to the front (see Figure 1). To assess modifications in locomotor posture (Figure 1), the coder scored infants’ carrying posture (crawling, walking, cruising, hitching, holding mother’s hand). To assess the destination and outcome of each bout, the coder noted whether infants carried objects in the direction of their mother, carried objects to another object or place, or stopped with no clear destination (stood still while holding the object or stopped to play with object). Object drops and infant falls were also coded. Drops were coded when infants lost grip on the object while still in motion; falls were coded when infants lost balance while upright or crawling and their bodies dropped to the floor. To determine whether carrying affected the frequency of falling, falls during bouts of walking without carrying were also noted.

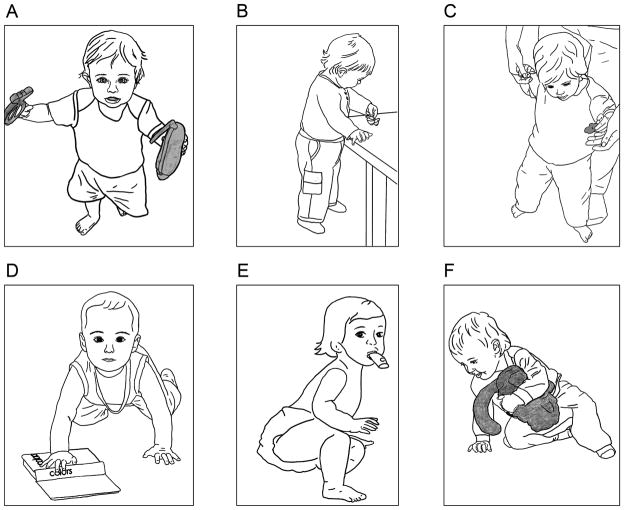

Figure 1.

Line drawings from video files illustrating some of the ways infants coordinated manual and locomotor actions to carry objects. A) Walking upright carrying an object in each hand to each side of the body so that the load is relatively symmetrical; B) Cruising sideways while gripping furniture for support and holding the object asymmetrically to one side of the body; C) Walking while holding caregiver’s hand and the object; D) Crawling on hands and knees and pushing the object along the floor; E) Hitching in a sitting position while carrying the object in the mouth; F) Crawling and clutching the object under one arm.

Results

Effects of Locomotor Status and Experience

Almost all infants (90%) carried objects. All of the walkers carried objects at least once. To our surprise, most crawlers (81%) also carried objects. Five crawlers never carried objects. These infants did not differ from the rest of the sample in terms of crawling onset age or locomotor experience. They were not considered in subsequent analyses.

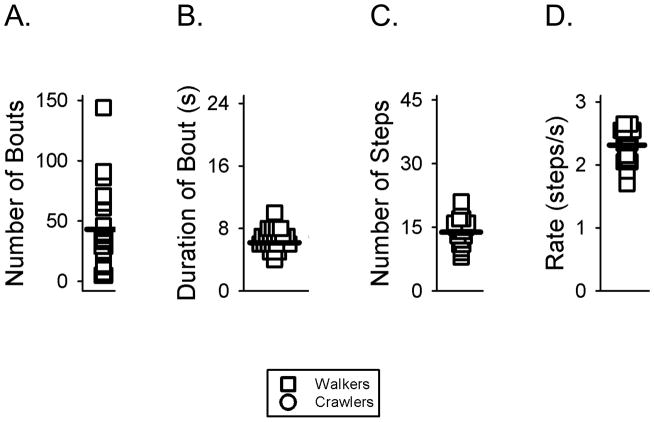

Walkers carried more frequently than crawlers. The frequency of carrying bouts ranged from 5 to 144 (M = 43.1) for walkers and from 1 to 25 (M = 6.3) for the 21 crawlers who carried (Figure 2A). Put another way, walkers carried an object every 1.4 minutes and crawlers carried every 9.5 minutes. The busiest walker transported an object every 25 seconds. The time between carrying bouts was generally long for both groups (M = 2.4 min for walkers, SD = 2.8 and M = 5.9 min for crawlers, SD = 4.8). Most pauses between bouts (90%) were greater than 3 s, and 75% of pauses were greater than 5 s, suggesting that carrying bouts were distinct events rather than continuous treks interrupted by trivial pauses in ongoing locomotion.

Figure 2.

The frequency and quality of object carrying. (A) Number of carrying bouts accumulated over the observation hour, (B) average duration of carrying bouts, (C) average number of steps taken within carrying bouts, (D) average rate of carrying. Squares and circles represent data from individual walking and crawling infants. Horizontal lines depict group means.

The duration of carrying bouts was similarly brief for walkers (M = 6.18 s, SD = 1.30) and crawlers (M = 6.91 s, SD = 4.27), see Figure 2B. However, as shown in Figure 2C–D, walkers tended to take more steps per bout (M = 13.85, SD = 3.14) than crawlers (M =10.50, SD = 7.61), and they took more steps per second (M = 2.31, SD = 0.27) than crawlers (M = 1.58, SD = 0.34), suggesting that they also covered more ground with each carrying bout.

In 9 infants, we were able to compare carrying while walking and crawling. These infants sometimes carried objects while crawling on hands and knees, so that we could compare the frequency and quality of their movements when carrying in the two postures. Confirming the between-group differences in walkers and crawlers, infants carried more frequently while walking (M = 31.3, SD = 21.0) than crawling (M = 6.2, SD = 10.0). Moreover, when carrying in a walking posture they took more steps (M = 14.4 steps, SD = 2.4) and took more steps per second (M = 2.3 steps/sec, SD = 0.2) than when carrying in a crawling posture (Ms = 9.0 steps and 1.7 steps/sec, SDs = 4.0 and 0.5, respectively; paired ts = 4.32, 4.07, ps < .05, for steps and steps/sec respectively.

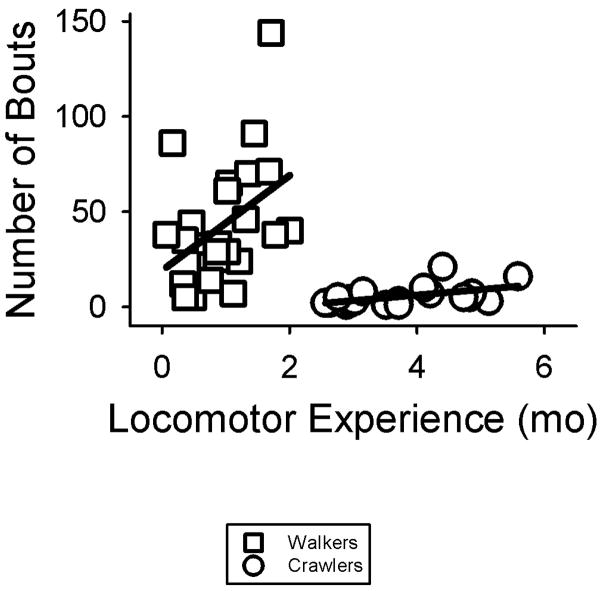

As shown by the scatter of symbols within each locomotor group in Figure 3, locomotor experience predicted individual differences in carrying frequency. The least experienced walker (2 days of walking experience) carried objects 38 times per hour, considerably more than the 16 bouts displayed by the most experienced crawler (170 days of crawling experience). More experienced walkers (square symbols) carried more frequently, Pearson r(22) = .41, p < .05, as did more experienced crawlers (circular symbols), Pearson r(17) = .52, p < .05. For walkers, average step frequency while carrying was correlated with walking experience, Pearson r(22) = .50, p < .05, but for crawlers, it was not.

Figure 3.

Bivariate association between locomotor experience and frequency of carrying bouts. Walking experience predicted the frequency of carrying bouts in walkers and crawling experience predicted the frequency of carrying bouts in crawlers.

Selecting Objects

Infants carried single objects (M = 89% of carry bouts, SD = 18%) more frequently than multiple objects (M = 11%, SD = 18%), meaning that they were more likely to carry objects asymmetrically than symmetrically. However, of the bouts when infants carried multiple objects, walkers (M = 16% of carry bouts, SD = 18%) were more likely than crawlers (M = 4%, SD = 17%) to carry symmetrically (an object in each hand positioned to each side of the body), and more experienced walkers were more likely to carry symmetrically than less experienced walkers, r(22) = .47, p < .05. Only two crawlers carried objects symmetrically; they averaged 5.36 months of crawling experience, the two most experienced infants in the crawler group.

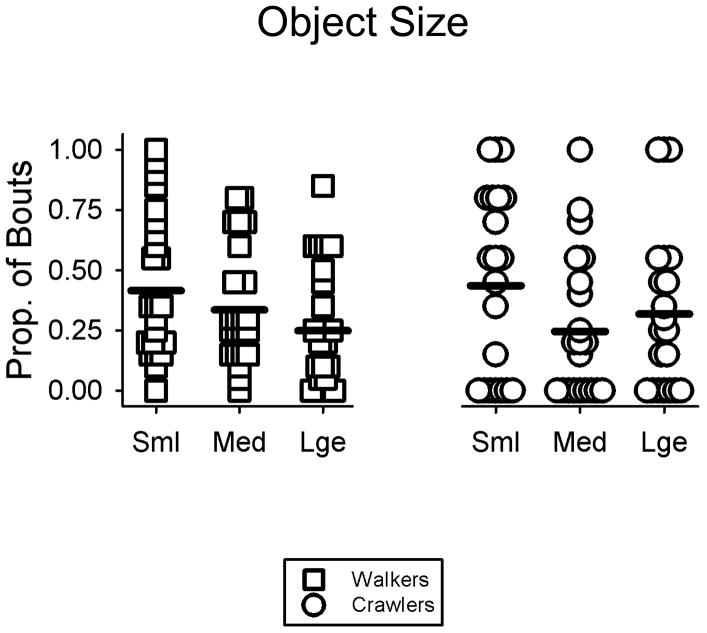

On average, more carrying bouts involved small objects (M = 42.5% of carry bouts, SD = 33.6%) than medium (M = 29.4%, SD = 26.7%) or large objects (M = 28.2%, SD = 29.2%) (Figure 4). Large objects (e.g., board book, photo album, baby doll, roll of paper towels, computer keyboard, bin of toys) were more ungainly, typically held with two hands, with infants clutching the object to their chests or pushing the object along the floor with their hands. More carrying bouts involved toys (M = 53% of carry bouts, SD = 34%) than books (M = 10%, SD = 19%), food (M = 7%, SD = 17%), or household items (M = 19%, SD = 25%). Object type and size were not related to locomotor experience and did not affect the distance infants traveled or their step frequency.

Figure 4.

Frequency of selecting objects of different sizes represented as a proportion of carrying bouts. Squares and circles represent data from individual walking and crawling infants. Horizontal lines depict group means.

Carrying Posture

As illustrated in Figure 1, various ways of coordinating manual and locomotor postures were possible for carrying objects. However, infants primarily carried objects in their hands (M = 90% of carry bouts, SD = 23.7%). More rarified methods included pushing objects along the floor (M = 9%, SD = 23.5%), carrying objects in the mouth (M = 1%, SD = 4.6%), or gripping objects under an arm (M = 0.3%, SD = 1.4%). Five walkers and 6 crawlers pushed objects, all in crawling positions. Four infants carried objects in their mouth: one crawler in a hitching position, two walkers in crawling positions, and one walker while upright. Two infants gripped objects under their arms.

Walkers used fewer locomotor postures than crawlers to transport objects. Walkers carried while walking on M = 94.3% of carry bouts (SD = 12.7%), whereas crawlers only carried while crawling on M = 54.0% of carry bouts (SD = 42.3%). Nine walkers and 9 crawlers used more than 1 posture to carry. Walkers with more walking experience solely carried while walking and walkers with less experience used more than 1 posture; conversely, crawlers with more crawling experience, used more than 1 posture to carry, whereas crawlers with less experience simply crawled. A 2 (walker/crawler) × 2 (single vs. multiple postures) ANOVA on months of locomotor experience confirmed a significant locomotor status by posture interaction, F(1, 39) = 10.67, p < .05.

Destination

Most frequently, infants transported objects with no apparent object-related or mother-related destination. On M = 56% of carry bouts (SD = 24%), they carried objects several feet and then stood there looking around or plopped down to play with the object. On M = 24% (SD = 23%), they used the carried object to interact with another object at the new location and on M = 20% of bouts (SD = 22%), they carried objects to their mothers. Walkers had fewer object-related destinations (M = 16%, SD = 11%) than crawlers (M = 33%, SD = 29%), t(42) = 2.68, p < .05, but the groups did not differ in mother-related destinations (Ms = 22% and 18%, SDs = 12% and 31%, for walkers and crawlers, respectively) or simply stopping with no known destination (Ms = 62% and 49%, SDs = 14% and 31%, for walkers and crawlers, respectively). A 2 (walker/crawler) × 3 (destination) ANOVA on the proportion of bouts confirmed a main effect for destination, F(2, 86) = 21.70, p < .001 and a destination by locomotor group interaction, F(2, 86) = 3.78, p < .05. Post hoc paired t-tests showed more stops with no known destinations than carrying toward objects or mothers, p < .001, and more object-related destinations for crawlers.

The distances infants traveled differed by destination. Walkers took more steps carrying objects to the middle of the room (M = 14.1, SD = 4.5) or to mother (M = 15.0, SD = 8.3) than to object-related destinations (M = 11.0, SD = 6.1). Crawlers took more steps traveling to the middle of the room (M = 8.9, SD = 9.0) or object-related destinations (M = 10.3, SD = 14.0) than to mothers (M = 3.2, SD = 5.0). A (walker/crawler) × 3 (destination) ANOVA on the number of steps per bout revealed a significant interaction between locomotor status and destination, F(2, 86) = 6.69, p < .01 and confirmed a main effect for locomotor status. For walkers, post hoc paired t-tests confirmed fewer steps to object-related destinations; for crawlers, post hoc paired-tests confirmed fewer steps to mother, ps < .05.

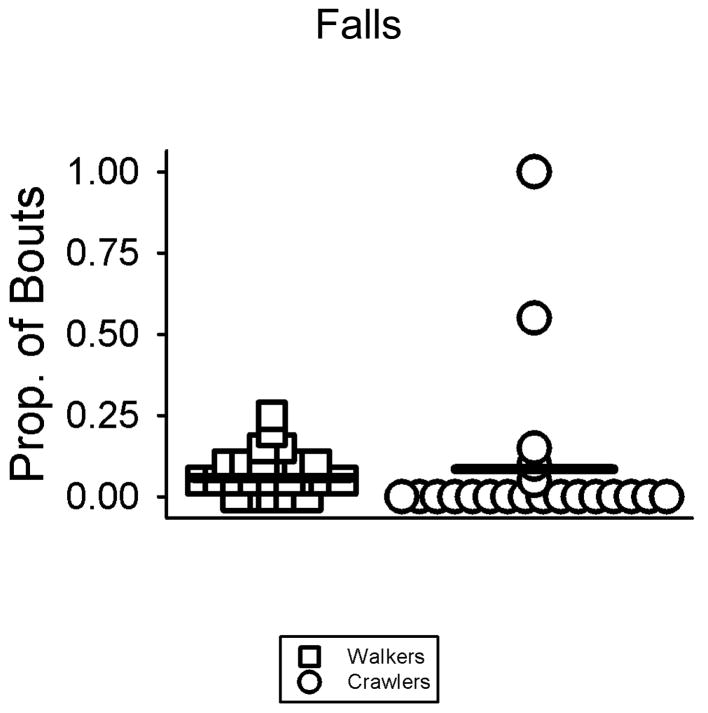

Drops and Falls

Most walkers fell (79% of infants) or dropped an object (63%) at least once, whereas most crawlers never fell (76%) or dropped the object (76%). However, most carrying bouts were completed successfully: The overall fall and drop rates were less than 10% for both groups (Figure 5). Walkers took more steps before falling (M = 16.9, SD = 21.6) or dropping the object (M = 6.1, SD = 5.6) compared with crawlers, who took only M = 3.7 steps (SD = 10.4) before falling and 2.5 steps before dropping (SD = 5.3). For walkers, the proportion of carry bouts that ended in falls was negatively correlated with walking experience, Pearson r(22) = −.45, p < .05, but for crawlers, proportion of falls was not related to crawling experience due the restricted range of falling. Experience was not related to dropping in either group.

Figure 5.

Frequency of falls represented as a proportion of carrying bouts. Squares and circles represent data from individual walking and crawling infants. Horizontal lines depict group means.

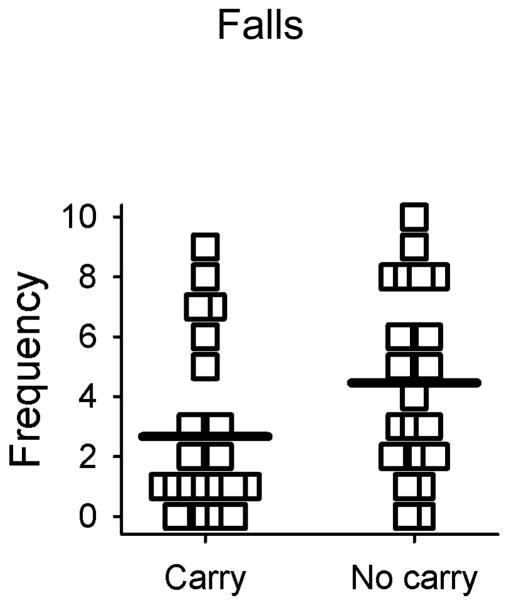

To our surprise, falling was less, not more, prevalent while walkers carried objects compared with falling without objects in hand (Figure 6). Most walkers fell (83.3%) at least once when not carrying objects, and they were nearly twice more likely to incur falls when not carrying (M = 4.5 falls, SD = 3.31) than when carrying objects (M = 2.7, SD = 2.8), paired t(23) = 2.41, p < .05.

Figure 6.

Frequency of falls for walkers when carrying objects and when not carrying. Squares represent data from individual walking infants. Horizontal lines depict group means.

Discussion

By the middle of their first year, infants can pick up objects and hold them in hand. By the beginning of their second year, infants can locomote from one place to another by crawling or walking. The current study described how infants coordinate manual and locomotor skills to hold and transport objects in the course of locomotion. In contrast to previous research, we focused on spontaneous carrying in the home rather than imposed load carriage in the lab. Of special interest were the effects of locomotor status (whether infants were crawlers or walkers) and locomotor experience (days of crawling or walking) on the frequency of carrying, selection of objects, adaptations in posture, destination, and success at carrying objects without dropping the object or falling.

Infants Carry Objects

Carrying was common: Overall, infants averaged 24 bouts of spontaneous carrying per hour. To put these numbers into perspective, for every hour of free play, 13-month-olds exhibit 41 bouts of object play (Karasik, et al., in press), generate 156 bouts of walking, travel an accumulated distance of 676 m, and fall 19 times (Adolph, et al., 2011). Thus, the combination of manual and locomotor skills involved in carrying objects represents about half of all contacts with objects and 15% of all bouts of locomotion. Although previous work on imposed load carriage showed that walking gait is more disrupted by heavier loads and asymmetrical loads, in the current study, infants appeared indifferent to object size and to the additional balance constraints involved in carrying objects to the front or side of their bodies. Possibly, when given the freedom to select objects of their own choosing, most selections were relatively light and inconsequential relative to loads in laboratory studies, but occasionally, we observed infants attempting some heavy lifting such as carrying large photo albums and step stools. Infants carried toys more frequently than other types of objects—probably because toys were the most prevalent objects strewn around the floor and reachable surfaces.

The act of carrying may be intrinsically rewarding. Parents often report that infants happily run around with objects in hand, and researchers frequently exploit infants’ love of carrying to induce them to walk back and forth in repeated trials in locomotor tasks (e.g., Schmuckler & Gibson, 1989). Despite the fact that walkers have a higher vantage point than crawlers that allows upright infants to see more of the room (Franchak, Kretch, Soska, & Adolph, in press), the goal for infants in both groups is carrying, not carrying toward a destination. Indeed, more than half of all carrying bouts ended with infants stopping in their tracks rather than transporting objects to a particular destination—another object or their mothers.

Hands Can Multi-task

One of the most important findings was that crawlers can and do carry objects. The longstanding assumption that crawlers do not carry objects because of their reliance on the hands for balance and propulsion and the evolutionary argument that carrying objects requires hands to be free are not supported by these infant data.

Infants can carry objects without using their hands: Infants tucked objects under their arms and carried objects in their mouths like a dog. Moreover, the hands can be free and used for transport in positions other than upright walking. For example, infants can locomote in a sitting position by scooting on their bottoms and several infants carried in this manner. The infant who bottom-shuffled instead of crawling on hands and knees accumulated 25 bouts of carrying, the highest rate of all non-walking infants.

Finally, the hands can multi-task: Infants crawled on hands and knees with objects held in their hands, they pushed objects along the ground while supporting their body weight on their hands, and they cruised hanging onto furniture while gripping objects in hand. They distributed the transport and support functions of the hands and devised alternative ways to move the body forward to compensate for the added object.

Although crawlers can carry objects, not surprisingly, the rate of object transport was dramatically higher in walkers, and 5 crawlers never carried. The surprise is the high rate of carrying in even the least experienced walkers who typically walk with their arms raised as if for balance (Ledebt, 2000) and who were most perturbed by imposed loads in previous research (Garciaguirre, et al., 2007; Vereijken, et al., 2009). In fact, the least experienced walker spontaneously carried more than twice as often as the most experienced crawler.

How might we reconcile the fact that an upright hands-free posture is not necessary for carrying objects yet carrying is more prevalent at all stages of walking compared with crawling? Upright walking is a more efficient means of locomotion than crawling, and possibly transporting objects comes along for the ride. Novice walkers move twice as fast, take twice the number of steps, and travel three times the distance in their first weeks of walking as experienced crawlers do in their last weeks of crawling (Adolph, 2008; Adolph et al., 2011). After infants can string together a series of consecutive walking steps, the ability to walk provides them with a more time-efficient mode of travel than crawling or bum shuffling. Indeed, when we compared the quality of carrying in the same infants who carried while walking and sometimes while crawling, infants took more steps and took more steps per second when carrying in their new walking posture than in their more familiar crawling posture.

Costs of Carrying

Both crawlers and walkers were highly successful in carrying. Less than 10% of carrying bouts ended with infants falling while carrying the object. However, previous studies of imposed load carriage found a substantial increase in gait disruptions: 25% to 60% of trials when loaded with weights compared to 6% to 14% with no weights (Garciaguirre, et al., 2007; Vereijken, et al., 2009). The discrepancy between falling during spontaneous carrying at home and imposed load carriage in the lab may be due to differences in the amount of the loads (15%–25% of body weight in the lab studies) or the location of loads on infants’ bodies (shoulders, hips, and ankles in the lab studies).

An unexpected finding was that falls were more frequent while not carrying objects than while carrying. Walkers fell twice as often with no objects in hand than while carrying objects. One possibility is that walkers are more careful when engaged in an attention-demanding task such as carrying objects. Studies with adults show that when performing an attention-demanding task, posture becomes more stable (Stoffregen, Pagulayan, Bardy, & Hettinger, 2000). Perhaps infants show improved balance control when attending to an object while locomoting. Another possibility is that holding onto something while locomoting may have given infants the confidence to take independent steps. This effect is similar to a newly walking infant barely grazing the surface of furniture or caregiver’s finger in the chance of a fall; just a mere iota of support is enough to sustain upright balance (Chen, Metcalfe, Jeka, & Clark, 2007). In a wonderful historical anecdote, Trettien (1900) described how G. Stanley Hall’s child was inspired to walk by holding her father’s shirt cuffs in each hand. Much to her father’s surprise, while holding the cuffs, she walked proudly, but without the cuffs, she refused to take a single step. The cuffs served as a temporary crutch for the child; after two days of walking only with cuffs in hand, she eventually built up the confidence to walk without them.

Locomotor Experience Facilitates Carrying

Crawling and walking experience was related to the frequency of object carrying, adaptations in posture for carrying, and rate of falling while carrying. More experienced crawlers and walkers carried objects more frequently. These findings are consistent with laboratory studies of imposed load carriage (Garciaguirre, et al., 2007; Vereijken, et al., 2009): Over weeks of walking, infants were less likely to refuse to walk while carrying loads and increasingly managed to walk across the walkway successfully.

Locomotor experience was also associated with how infants coordinated manual and locomotor actions to carry objects. More experienced crawlers used a variety of postural strategies, frequently adjusting their locomotor posture to carry objects. These findings are consistent with previous studies showing that experienced crawlers invent alternative ways when crossing risky ground and often explore a variety of locomotor possibilities before settling on the most optimal strategy (Adolph, 1997; Kretch, Karasik, & Adolph, 2009, October). The opposite pattern was revealed for walkers. Walkers using a single walk-only strategy were, on average, more experienced than walkers using multiple strategies, suggesting that less experienced walkers may have been forced to revert to alternative methods of locomotion. A related possibility is that gains in walking experience may be related to a decrease in locomotor variability. Indeed, other researchers have found that novice walkers frequently revert to crawling in the context of spontaneous locomotion (Badaly & Adolph, 2008).

As expected, duration of walking experience was related to the rate of falling in the walkers. As in previous work, less experienced walkers fell more frequently. However, it was not the objects that induced the falls, rather the opposite: Infants fell more frequently without an object in hand than while carrying objects. Locomotor experience appears to facilitate infants’ control over their bodies so infants fall less with gains in experience. Object carrying may serve the same function in the short term. Carrying objects may help infants to focus attention, stabilize balance, and minimize falls when they first begin to walk.

Conclusions

Laboratory experiments tell us what infants can do and home observations tell us what infants actually do. By observing spontaneous carrying in infants’ homes rather than imposed load carriage in the lab, we discovered that the coordination of manual and locomotor skills begins in early stages of mobility, before infants can walk upright. Object transport is frequent and appears to come without incurring increased risk of falling. Although loads by definition alter the biomechanical constraints on balance, and ostensibly make balance more difficult, spontaneous object transport appeared to stabilize infants’ balance regardless of size and symmetry of the object’s position. This is a good thing in terms of development. Carrying provides opportunities for learning about object properties and their affordances and for engaging in new kinds of interactions with the world (Gibson, 1988; Karasik, et al., in press).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NICHD Grant R37-HD33486 to KEA and NICHD R01-HD42697 to KEA and CTL. We thank the NYU Infant Action Lab for their assistance and for comments on earlier versions of this draft. We gratefully acknowledge the efforts of the parents and infants who participated in this study.

References

- Adolph KE. Learning in the development of infant locomotion. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1997;62(3) doi: 10.2307/1166199. Serial No. 251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolph KE. The growing body in action: What infant locomotion tells us about perceptually guided action. In: Klatzy R, Behrmann M, MacWhinney B, editors. Embodiment, ego-space, and action. Mahwah: Erlbaum; 2008. pp. 275–321. [Google Scholar]

- Adolph KE, Avolio AM. Walking infants adapt locomotion to changing body dimensions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2000;26:1148–1166. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.26.3.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolph KE, Berger SE. Motor development. In: Kuhn D, Siegler RS, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 2. Cognition, perception, and language. 6. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2006. pp. 161–213. [Google Scholar]

- Adolph KE, Berger SE, Leo AJ. Developmental continuity? Crawling, cruising, and walking. Developmental Science. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.00981.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolph KE, Komati M, Garciaguirre JS, Badaly D, Sotsky RB. How do you learn to walk? Thousands of steps and hundreds of falls per day. 2011 doi: 10.1177/0956797612446346. Manuscript under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolph KE, Vereijken B, Shrout PE. What changes in infant walking and why. Child Development. 2003;74:474–497. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.7402011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badaly D, Adolph KE. Walkers on the go, crawlers in the shadow: 12-month-old infants’ locomotor experience. Poster presented at the International Conference on Infant Studies; Vancouver, Canada. 2008. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Bertenthal BI, Clifton RK. Perception and action. In: Kuhn D, Siegler RS, editors. Handbook of Child Psychology, Vol. 2: Cognition, Perception, and Language. 5. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1998. pp. 51–102. [Google Scholar]

- Bril B, Breniere Y. Steady-state velocity and temporal structure of gait during the first six months of autonomous walking. Human Movement Science. 1989;8:99–122. doi: 10.1016/0167-9457(89)90012–2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bushnell E, Baxter K, Fitzgerald J, Clearfield MW. New walkers’ responses to the challenges of carrying objects. Paper presented at the meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Denver, CO. 2009. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Chen L-C, Metcalfe JS, Jeka JJ, Clark JE. Two steps forward and one back: Learning to walk affects infants’ sitting posture. Infant Behavior & Development. 2007;30:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchak JM, Kretch KS, Soska KC, Adolph KE. Infants’ view of the world: What head-mounted eye-tracking reveals about infants’ natural encounters with obstacles, objects, and people. Child Development in press. [Google Scholar]

- Garciaguirre JS, Adolph KE, Shrout PE. Baby carriage: Infants walking with loads. Child Development. 2007;78:664–680. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson EJ. Exploratory behavior in the development of perceiving, acting, and the acquiring of knowledge. Annual Review of Psychology. 1988;39:1–41. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.39.020188.000245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hewes G. Food transport and the origin of hominid bipedalism. American Anthropologist. 1961;63:687–710. doi: 10.1525/aa.1962.64.3.02a00110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karasik LB, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Adolph KE. Transition from crawling to walking and infants’ actions with objects and people. Child Development. 2011;82:1199–1209. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01595.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretch KS, Karasik LB, Adolph KE. Cliff or step: Posture-specific learning at the edge of a drop-off. Paper presented at the meeting of the International Society for Developmental Psychobiology; Chicago. 2009. Oct, [Google Scholar]

- Kubo M, Ulrich B. A biomechanical analysis of the ’high guard’ position of arms during walking in toddlers. Infant Behavior & Development. 2006;29:509–517. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledebt A. Changes in arm posture during the early acquisition of walking. Infant Behavior & Development. 2000;23:79–89. doi: 10.1016/S0163-6383(00)00027-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw MB. The neuromuscular maturation of the human infant. New York: Columbia University Press; 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Robson P. Prewalking locomotor movements and their use in predicting standing and walking. Child: Care, health, and development. 1984;10:317–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.1984.tb00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson PM, Scott JJP, Johnston T, Mainzer J, Wantanbe LM, James JM. MacSHAPA and the enterprise of Exploratory Sequential Data Analysis (ESDA) International Journal of Human-Computer Studies. 1994;41:633–681. doi: 10.1006/ijhc.1994.1077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmuckler MA. Perception-action coupling in infancy. In: Savelsbergh GJP, editor. The development of coordination in infancy. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 1993. pp. 137–173. [Google Scholar]

- Schmuckler MA, Gibson EJ. The effect of imposed optical flow on guided locomotion in young walkers. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 1989;7:193–206. [Google Scholar]

- Stanford CB. Upright: The evolutionary key to becoming human. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffregen TA, Pagulayan RJ, Bardy BB, Hettinger LJ. Modulating postural control to facilitate visual performance. Human Movement Science. 2000;19:203–220. doi: 10.1016/S0167–9457(00)00009-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trettien AW. Creeping and walking. The American Journal of Psychology. 1900;12:1–57. doi: 10.2307/1412427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vereijken B, Pedersen AV, Storksen JH. Early independent walking: A longitudinal study of load perturbation effects. Developmental Psychobiology. 2009;51:374–383. doi: 10.1002/dev.20377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Videan EN, McGrew WC. Bipedality in chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) and bonobo (Pan paniscus): Testing hypotheses on the evolution of bipedalism. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 2002;118:184–190. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.10058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]