Abstract

Osteoporosis often results in fractures, deformity and disability. A rare but potentially challenging complication of osteoporosis is a sternal insufficiency fracture. This case report details a steroid-induced osteoporotic male who suffered a sternal insufficiency fracture after minimal trauma. Prompt diagnosis and appropriate management resulted in favourable outcome for the fracture, though a sequalae involving a myocardial infarction ensued with his osteoporosis and complex health history. The purpose of this case report is to heighten awareness around distinct characteristics of sternal fractures in osteoporotic patients. Discussion focuses on the incidence, mechanism, associated factors and diagnostic challenge of sternal insufficiency fractures. This case report highlights the role primary contact practitioners can play in recognition and management of sternal insufficiency fractures related to osteoporosis.

Keywords: sternal fracture, osteoporosis, insufficiency fracture

Abstract

L’ostéoporose cause souvent des fractures, des difformités et l’invalidité. Une complication rare, mais potentiellement grave, de l’ostéoporose est la fracture par insuffisance osseuse du sternum. Ce rapport décrit en détail le cas d’un mâle atteint d’ostéoporose causée par les stéroïdes et qui a subi une fracture par insuffisance osseuse du sternum après un traumatisme minime. Grâce à un diagnostic rapide et une gestion appropriée, on a obtenu de bons résultats pour la fracture, mais des séquelles ont été laissées sous forme d’un infarctus du myocarde en raison de ses antécédents médicaux complexes. Le but de cette étude de cas est de sensibiliser sur les caractéristiques distinctes des fractures du sternum chez les patients ostéoporotiques. La discussion porte sur l’incidence, le mécanisme, les facteurs associés et la difficulté de diagnostic des fractures par insuffisance osseuse du sternum. Cette étude de cas met en évidence le rôle que peuvent jouer les chiropraticiens qui offrent des soins primaires dans le diagnostic et la gestion des fractures par insuffisance osseuse du sternum liées à l’ostéoporose.

Keywords: fracture du sternum, ostéoporose, fracture par insuffisance osseuse

Introduction

Osteoporosis affects approximately 1.4 million Canadians, mainly postmenopausal and elderly individuals.1 Patients with one or more vertebral fractures are 4–5 times more likely to have a subsequent vertebral fracture.2 There is also significant risk for fractures at the hip3–4 and wrist5, leading to further disability and increased economic burden to society. Authors have proposed that sternal fractures, a rare complication of osteoporosis, are not well understood.6–8 Pathogenesis of this condition in osteoporotic patients, and its impact on subsequent fracture risk and overall health, is unclear. Although the clinical presentation and management of isolated sternal fractures are well known in the general population9,10, they may have distinct characteristics in those with osteoporosis, making it difficult for recognition and management among primary contact providers.

This case report (event timeline outlined in Table 1) describes a steroid-induced osteoporotic patient, with a history of multiple vertebral compression fractures, suffering a sternal insufficiency fracture, and later experiencing a complex sequalae involving a myocardial infarction (MI) related to his osteoporosis and co-morbidities. The incidence, mechanism, associated factors and diagnostic characteristics of sternal fractures in the osteoporotic population will be discussed. In light of the MI that occurred in this patient’s long-term follow-up, the case also discusses the potential relationship between MI and low bone mineral density (BMD) with osteoporosis.

Table 1:

Timeline of Events

| Week | Event |

|---|---|

| 1 | Two-stage kyphoplasty for new compression fractures (T12-L5) |

| 8 | Onset of chest pain after reaching into refrigerator |

| 10 | Diagnosis of sternal insufficiency fracture (confirmed on radiographs) Treatment with pain medication and monitoring |

| 26 | Resolution of symptoms related to sternal insufficiency fracture Diagnosis of new compression fractures (T7-T8) |

| 27 | Kyphoplasty for compression fractures (T7-T8) |

| 33 | Onset of left rib pain and recurrence of upper thoracic pain Treatment with pain medications and monitoring |

| 35 | Onset of chest pain radiating to left arm – sent to emergency Diagnosis of ST-elevated myocardial infarction Treatment with medication; discharge 2 days later in stable condition |

Case Report

A 56 year-old steroid-induced osteoporotic male presented to his orthopaedic surgeon for post-operative follow-up. Ten weeks prior to this follow-up appointment, he had recurrent back pain diagnosed as vertebral compression fractures, for which he received two-stage kyphoplasty to T12, L1 and L4 (first stage), and L2, L3 and L5 (second stage), completed two days apart. The patient reported immediate improvement in pain and was discharged the next day after an uneventful post-operative course. He was given oxycodone/acetaminophen and scheduled for follow-up in 6–8 weeks. His medical history was remarkable for asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple previous chest infections and previous compression fractures (treated with kyphoplasty at T9, T10, and T11). His long-standing use of medications consisted of methylprednisone for rheumatoid arthritis (4 mg once daily, patient titrated as needed); albuterol (four puffs 4 times daily, and every 2 hours as needed), budesonide (two puffs 2 times daily), budesonide/formoterol inhaler (two puffs 2 times daily), and ipratropium bromide inhaler (two puffs 4 times daily) for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; a course of alendronic acid/colecalciferol (had completed course of teriparatide), calcium and vitamin D for osteoporosis. The patient was a non-smoker with no personal/family history of coronary artery disease.

At follow-up with the orthopaedic surgeon, his pain from compression fractures was significantly reduced, but he was now presenting with anterior midline chest and upper thoracic pain of two weeks’ duration that started after reaching into the refrigerator. Presenting after minimal trauma, the pain was localized to mid-sternum and midline upper thoracic spine. No neurological symptoms were reported. At this time, the patient was not taking any medication for the pain. On physical examination, severe anterior head carriage and thoracic kyphosis was noted, visually estimated to be 70–80 degrees of thoracic kyphosis with the curve apex at the mid-thoracic spine level. The patient used a cane minimally and was slow in ambulation due to postural imbalances related to his severe kyphosis. Light palpation of mid-sternum in the anterior-to-posterior direction revealed crepitation and reproduced the chest pain. Sternal radiographs revealed a fracture subluxation with slight step deformity in mid-portion of the sternum, corresponding to the painful area clinically (Figure 1). Thoracic radiographs revealed no new fractures in the upper thoracic spine (Figure 2). Since the sternal fracture was evident on radiograph and clinically correlated with his symptoms, a diagnosis of sternal fracture was given and no additional tests were ordered at the time. The isolated sternal fracture was managed conservatively with oxycodone (1–2 tablets every 4–6 hours as needed), acetylsalicylic acid (325 mg once daily for 30 days, then 81 mg once daily) and monitoring.

Figure 1:

Lateral spot-view radiograph of the sternum reveals fracture of the sternal body. There is interval development of a new fracture in the proximal portion of the sternal body (arrow).

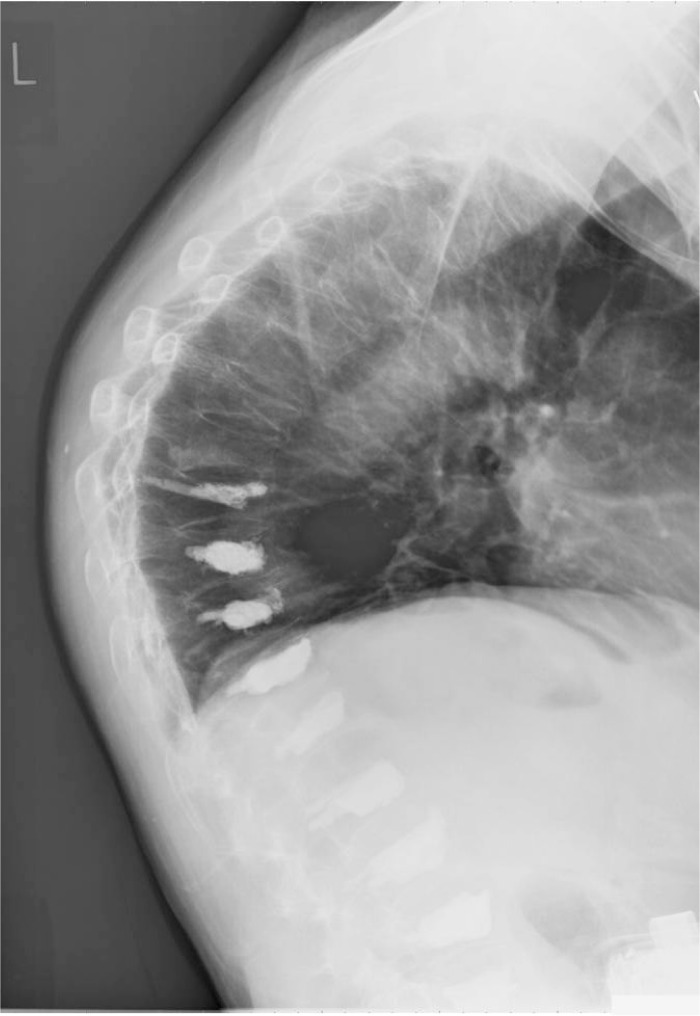

Figure 2:

Lateral thoracolumbar radiograph reveals previous kyphoplasty procedures at T9, T10, T11, T12, L1, L2, L3, L4 and L5. Contrast agents are confined to the vertebral bodies with no significant leaks. Old compression fractures suspected at T7 and T8. There is generalized decrease in bone density and multilevel degenerative changes.

With monitoring, the sternal fracture pain improved with pain medication and clinically resolved after 16–17 weeks. However, the patient experienced recurrent back pain, confirmed as new compression fractures at T7 and T8 at visits with the orthopaedic surgeon, and the pain decreased significantly after kyphoplasty to these segments. Six weeks after kyphoplasty, the patient presented with diffuse pain in the left mid ribs and a recurrence of upper thoracic pain, and watchful waiting was decided upon.

Long-Term Follow-up:

Two weeks later, the patient reported midline chest pain 40–60 minutes prior to his arrival to the emergency department, of 8/10 in severity that radiated to his left arm. There was no nausea, vomiting, shortness of breath or diaphoresis. One week prior, the patient went to a walk-in clinic for recurrent left shoulder and arm pain and received pain medication. On examination, the patient was alert, oriented, in no acute distress and able to complete full sentences. Cardiovascular, respiratory, abdominal and neurological examinations were normal. The patient had distal pulses positive and cool extremities bilaterally, but no tender calves or significant edema.

Laboratory results revealed troponin at less than 0.01 and creatine kinase of 36. Chest radiographs found no obvious consolidation or sternal fracture. Echocardiogram and coronary angiography revealed an inferior ST-elevated MI, a 100% occlusion (< 1 mm) of a small distal pulmonary venous branch of right coronary artery and mild inferior hypokinesis. Due to the small occlusion size, the ST-elevated MI was managed with clopidogrel bisulfate, acetylsalicylic acid, heparin, antibiotics and a refill of respiratory medications, while respiratory status was monitored in the coronary care unit. On discharge 2 days later, the patient was neurologically intact, in stable condition and was to continue post-MI management at home with follow-up from his medical doctor, specialists and community care services.

Discussion

Incidence:

Sternal fractures are rare, with a reported incidence of 0.5% of all bony fractures6, and often by major trauma like motor vehicle accidents. Of all sternal fractures presenting to emergency in a 6.5-year timeframe, 92.3% of 272 cases were related to motor vehicle accidents and 7.7% were due to direct sternal trauma.9 Few reports have documented a sternal fracture in an osteoporotic individual, known as an insufficiency or fragility fracture, which is a stress fracture in bones with decreased mineralization and elastic resistance.7 In a retrospective survey of all insufficiency fractures except spinal fractures, only one sternal fracture (1.1%) was identified among 91 insufficiency fractures.8 In a recent review, most sternal insufficiency fractures were due to some form of high or low degree of trauma, such as a fall from standing.7 However, the sternal fracture in our case was from reaching into a refrigerator, which is considered minimal trauma, occurring 10 weeks after kyphoplasty was performed for multiple compression fractures. This warrants a closer investigation on the role osteoporosis may have on the sternum.

Mechanism and Associated Factors:

While the etiology of sternal insufficiency fractures is not well understood, generalised bone changes in osteoporosis plays an important role. Trabecular bone changes during osteoporosis have been shown to increase risk for subsequent fractures. Known as the fracture cascade phenomenon of osteoporosis11, this may occur in sites other than the spine, but to a lesser extent. For example, a vertebral fracture also increases the risk of subsequent hip fracture by 3-fold.3 Histomorphometric bone analyses from iliac crest have reportedly found anistrophic trabecular changes in individuals with osteoporotic vertebral fractures, including fewer trabeculae, greater trabecular spacing, lower osteocyte density and reduced cortical thickness.11 Since the sternum is a flat bone comprised of two thin layers of compact bone surrounding trabecular bone, it may be susceptible to such microarchitectural disruption.

Biomechanical factors may compound trabecular effects and increase fracture risk. Some propose that increased thoracic kyphosis from compression fractures transfer axial force loads from spine to sternum and increases fracture risk.6,7,12,13 A recent dynamic systems model describes multidimensional risk factors to osteoporotic fractures, including altered bone quality and density, local and global spine changes, and aberrant biomechanics.12 While load transference in biomechanics is discussed in this model, its impact on bony structures anteriorly, such as the sternum, is not considered; the model is limited to changes along the spine and paraspinal musculature. This case report sheds further light on this cascade and may suggest the need for a broader anatomical perspective when considering altered biomechanics and trabecular changes in osteoporosis.

In this patient, a number of factors may have contributed to the sternal fracture. In addition to his severe thoracic kyphosis and longstanding osteoporosis, the patient had a two-stage kyphoplasty procedure 10 weeks prior to the sternal insufficiency fracture, where he laid prone on a surgical table that supported the weight of his chest through a padded horizontal chest bolster across the sternum. In subsequent kyphoplasties, the placement of bolsters on the surgical bed was changed to two vertical bolsters from the iliac crest to the shoulders to prevent direct pressure on his sternum. For patients undergoing kyphoplasty and had previously suffered a sternal insufficiency fracture, this simple, no-cost repositioning of the surgical table bolsters may be indicated to decrease pain and risk of further complications at the sternal fracture site.

Clinical Presentation and Significance:

The variable clinical presentation of sternal fractures can be a diagnostic challenge in differentiating it from other conditions. Chen reported that in 7 cases of sternal insufficiency fractures, 2 buckling fractures were asymptomatic while 5 non-buckling fractures were painful.13 However, Min and Sung reported that 5 of 7 patients with buckling sternal fracture had chest pain.14 Two previous cases also presented with such severe anterior chest pain that they were suspected as myocardial infarctions.7 Our patient complained of moderately intense anterior chest pain of two weeks duration, noted as local tenderness and crepitation during sternal palpation. A clinical index of suspicion for sternal fracture allowed for appropriate management, which involved sternal radiographs to confirm the diagnosis. Although sternal fractures as a complication of osteoporosis are relatively rare, it should be recognized that clinical presentation can range from asymptomatic to severe pain and should be a differential diagnosis for osteoporotic patients with chest pain.

Literature is mixed regarding prognosis and calls for differentiation between traumatic and insufficiency fractures. In traumatic cases, it has been suggested that computed tomography should follow radiographs to evaluate the extent of sternal and episternal injuries.10 However, isolated sternal fractures, likely in the case of insufficiency fractures, have a very good outcome15, as sternal fractures alone are reportedly not indicative of significant myocardial, mediastinal or thoracic aorta damage9. Our patient’s sternal insufficiency fracture was successfully managed with pain medication, and appeared to have healed within 16–17 weeks from onset.

Long-Term Sequalae of this Case:

Despite the favourable outcome of the sternal insufficiency fracture, the patient had complications related to his osteoporosis and complex health history. Two weeks after his sternal fracture appeared to have healed, he suffered a ST-elevated MI, which required immediate reperfusion therapy to avoid cardiogenic shock, especially within 12 hours of symptom onset and without contraindications.16 In this case, the recurrent anterior chest pain in our patient was not dismissed as residual pain from the preceding sternal fracture; instead, thorough investigation was conducted to rule out MI. The prompt diagnosis and management within 1 hour of symptom onset enabled the MI to be successfully managed medically with favourable short-term outcome.

Growing literature suggests a significant link between cardiovascular disease and low BMD, particularly between MI and future osteoporotic fracture risk. For instance, lower femoral neck and hip BMD has been significantly associated with increased risk of MI in both men and women, even after adjusting for smoking, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia and diabetes.17 Conversely, in a matched cohort study, a substantial increase in fracture risk (in all fracture sites) in survivors of MI was observed, a trend that has markedly increased over the past 3 decades.18 This population-based study noted an emerging association between MI and the risk of osteoporotic fracture in the community, a novel finding that was not observed in the general population.

Although there are possible confounders to the increased risk of fractures in MI survivors, recent literature suggests that these factors take a smaller role than previously thought. First, vitamin D and calcium supplements have been suggested to increase MI risk.19–21 Second, pharmacological agents could play a role, since MI patients often have comorbidities being managed pharmacologically.22–24 This includes medications for cardiovascular disease like heparin, oral anticoagulants and loop diuretics that can lead to drug-induced osteoporosis.25 However, the well-controlled 30-year longitudinal population-based study by Gerber et al still found a steady increase in osteoporotic fracture risk after MI, even after considering 19 serious comorbid conditions and stratifying for ST-elevated MI individuals who tend to be less frail and healthier.18 These analyses indirectly argue against the role of certain comorbidities and/or medications as primary explanations for the increase in fracture risk after MI, and emphasize the importance of considering a substantial fracture risk at all fracture sites in osteoporotic MI survivors.

It is important for chiropractors to be aware of potential complications associated with osteoporosis, particularly sternal insufficiency fractures and increased fracture risk after MI, as these patients may present on a monthly or annual basis. In 2010, in a combined online and mail survey of American chiropractors conducted by the National Board of Chiropractic Examiners with 3938 out of 9839 respondents (40% response rate), it was found that 3.7–3.8% of chief complaints from patients were related to chest pain.26 Although fractures were rarely (1–10x/year) seen by respondents in the past year, osteoporosis was more often seen by respondents, at a rate of 1–3x/month, where 70% of these cases were co-managed.26 Since sternal fractures in these patients may be biomechanically linked with high degrees of thoracic kyphosis, similar to previous sternal fracture cases with multiple compression fractures13, 27 and/or severe osteoporosis6,7, these individuals being seen by the chiropractor may be more frail, have more complex health conditions and require participation in secondary prevention programs and physical activity in preventing bone loss and falls28–30.

Conclusion

Although rare, sternal insufficiency fractures can present as challenges in the clinical setting, as they have variable clinical presentations and are often biomechanically linked to high degrees of thoracic kyphosis from multiple compression fractures in severe osteoporosis. This case report detailing a sternal insufficiency fracture in an osteoporotic male heightens awareness of their distinct characteristics in the osteoporotic population, aiding diagnosis and management by primary contact providers. In addition, this case report discusses the consideration of an increased fracture risk after a MI in osteoporotic patients, highlighting the integral role chiropractors can play in incorporating fracture prevention strategies in this patient population.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none

Consent: Patient gave written consent to use his file and images for the purpose of this case report. Approval for the case report was given by the Research Ethics Board at the Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College.

References

- 1.Goree R, O’Brien B, Pettitt D, et al. An assessment of the burden of illness due to osteoporosis in Canada. J Soc Obstet Gynaecol Can. 1996;18:15. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cauley JA, Hochberg MC, Lui LY, et al. Long-term risk of incident vertebral fractures. JAMA. 2007;298:2761e7. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.23.2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black DM, Arden NK, Palermo L. Prevalent vertebral deformities predict hip fractures and new vertebral deformities but not wrist fractures. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:821–828. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.5.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papadimitropouos EA, Coyte PC, Josse RG, Greenwood CE. Current and projected rates of hip fracture in Canada. Can Med Assoc J. 1997;158:870–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hodsman AB, Leslie WD, Tsang JF, Gamble GD. 10-year probability of recurrent fractures following wrist and other osteoporotic fractures in a large clinical cohort: an analysis from the Manitoba bone density program. Arch Intern Med. 2010;168(20):2261–2267. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.20.2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown SM, Chew FS. Osteoporotic manubrial fracture following a fall. Radiology Case Reports. 2006;1(4):116–119. doi: 10.2484/rcr.v1i4.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horikawa A, Miyakoshi N, Kodama H, Shimada Y. Insufficiency fracture of the sternum simulating myocardial infarction: case report and review of the literature. Exp Med. 2007;211:89–93. doi: 10.1620/tjem.211.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soubrier M, Dubost JJ, Boisgard S, Sauvezie B, Gaillard P. Insufficiency fracture: a survey of 60 cases and review of the literature. Joint Bone Spine. 2003;70:209–218. doi: 10.1016/s1297-319x(03)00024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brookes JG, Dunn RJ, Rogers IR. Sternal fractures: a retrospective analysis of 272 cases. J Trauma. 1993;35:46–54. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199307000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kehdy F, Richardson JD. The utility of 3-D CT scan in the diagnosis and evaluation of sternal fractures. J Trauma. 2006;60(3):635–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000204938.46034.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Briggs AM, Greig AM, Wark JD. The vertebral fracture cascade in osteoporosis: a review of aetiopathogenesis. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:575–584. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0304-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tyndyk MA, Barron V, McHugh PE. Effect of osteoporosis on the biomechanics of the thoracolumbar spine: finite element study. European Cells and Materials. 2005;10(3):73. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen C, Chandnani V, Kang HS, et al. Insufficiency fractures of the sternum caused by osteopenia: plain film findings in seven patients. Ann J Roentgenol. 1990;154:1025–1027. doi: 10.2214/ajr.154.5.2108537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Min JK, Sung MS. Insufficiency fractures of the sternum. Scand J Rheumatol. 2003;32:179–180. doi: 10.1080/03009740310002533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright SW. Myth of the dangerous sternal fracture. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22(10):1589–92. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)81265-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell-Scherer DL, Green LA. ACC/AHA guideline update for the management of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. American Family Physician. 2009;79(12):1080–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiklund P, Nordstrom A, Jansson JH, et al. Low bone mineral density is associated with increased risk for myocardial infarction in men and women. Osteoporos Int. 2011 Apr; doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1631-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerber Y, Melton LJ, Weston SA, Roger VL. Association between myocardial infarction and fractures: an emerging phenomenon. Circulation. 2011;124:297–303. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.007195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reid IR, Bolland MJ, Grey A. Effect of calcium supplementation on hip fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:1119–1123. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0563-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanders KM, Stuart AL, Williamson EJ, et al. Annual high-dose oral vitamin D and falls and fractures in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;303:1815–1822. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bolland MJ, Avenell A, Baron JA, et al. Effect of calcium supplements on risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular events: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c3691. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yeh RW, Sidney S, Chandra M, Sorel M, Selby JV, Go AS. Population trends in the incidence and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2155–2165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gandhi GY, Roger VL, Bailey KR, Palumbo PJ, Ransom JE, Leibson CL. Temporal trends in prevalence of diabetes mellitus in a population-based cohort of incident myocardial infarction and impact of diabetes on survival. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:1034–1040. doi: 10.4065/81.8.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Setoguchi S, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Mittleman MA, Levin R, Winkelmayer WC. Improvements in long-term mortality after myocardial infarction and increased use of cardiovascular drugs after discharge: a 10-year trend analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1247–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazziotti G, Canalis E, Giustina A. Drug-induced osteoporosis: mechanisms and clinical implications. Am J Med. 2010;123:877–884. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Board of Chiropractic Examiners Practice Analysis of Chiropractic 2010. Accessed March 8 2012: http://www.nbce.org/publication/practice-analysis.html.

- 27.Verwimp W. Images in clinical radiology: sternal insufficiency fracture. JBR-BTR. 2008;91:174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Witt BJ, Jacobsen SJ, Weston SA, Killian JM, Meverden RA, Allison TG, Reeder GS, Roger VL. Cardiac rehabilitation after myocardial infarction in the community. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:988–996. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ades PA. Cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:892–902. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra001529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vincent KR, Vincent HK. Resistance training for individuals with cardiovascular disease. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2006;26:207–216. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200607000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]