Abstract

Lentiviral vectors are efficient gene delivery vehicles for therapeutic and research applications. In contrast to oncoretroviral vectors, they are able to infect most nonproliferating cells. In the liver, induction of cell proliferation dramatically improved hepatocyte transduction using all types of retroviral vectors. However, the precise relationship between hepatocyte division and transduction efficiency has not been determined yet. Here we compared gene transfer efficiency in the liver after in vivo injection of recombinant lentiviral or Moloney murine leukemia viral (MoMuLV) vectors in hepatectomized rats treated or not with retrorsine, an alkaloid that blocks hepatocyte division and induces megalocytosis. Partial hepatectomy alone resulted in a similar increase in hepatocyte transduction using either vector. In retrorsine-treated and partially hepatectomized rats, transduction with MoMuLV vectors dropped dramatically. In contrast, we observed that retrorsine treatment combined with partial hepatectomy increased lentiviral transduction to higher levels than hepatectomy alone. Analysis of nuclear ploidy in single cells showed that a high level of transduction was associated with polyploidization. In conclusion, endoreplication could be exploited to improve the efficiency of liver-directed lentiviral gene therapy.

Pichard and colleagues examine the relationship between lentiviral transduction efficiency and the hepatocyte cell cycle. They demonstrate that in vivo retrorsine treatment, which blocks cells in interphase, combined with partial hepatectomy leads to a significant increase in lentiviral transduction in rats compared with hepatectomy alone. Subsequent analysis of nuclear ploidy in single cells revealed that high levels of transduction were associated with polyploidization.

Introduction

Recombinant lentiviruses are powerful vectors in the transfer of genes to a large variety of cells. One advantage of this viral vector is its ability to integrate into the genome of infected host cells. This ensures long-term expression of the transgene, in particular when the target cells are dividing cells. Another advantage of lentivirus-based vectors, in contrast to other retroviral vectors such as Moloney murine leukemia virus (MoMuLV) vectors, is their ability to infect nonproliferating cells in addition to dividing cells (Naldini et al., 1996; Zufferey et al., 1997). However, some exceptions may exist and, as an example, lentiviral vectors pseudotyped with a vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV)-G envelope gene do not easily transduce G0-arrested hematopoietic cells such as quiescent lymphocytes or macrophages (Zack et al., 1990; Kootstra et al., 2000).

Regarding the adult liver, in which hepatocytes are in G0, large amounts of lentiviral vectors are required to achieve transduction of a significant proportion of transduced hepatocytes in vivo in rodents after intravenous injection. Lentiviral transduction in quiescent mouse livers was studied by infusing various doses of a phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK)-nuclear localization signal (nls)-LacZ lentiviral vector into the portal vein of C57BL/6 mice (Park et al., 2000). At low doses of LacZ lentiviral vectors, a small proportion (<0.1%) of hepatocyte nuclei was positive for 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) whereas at higher doses the figure rose by more than 20-fold. In the same way, in another study we showed that the results of injection of recombinant lentiviral vectors carrying a green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter into mice aged 10 weeks were highly dependent on the amount of virus injected (Pichard et al., 2012). Although quiescent adult liver is poorly transduced by lentiviral vectors, a number of previous studies have shown that induction of cell proliferation dramatically improved liver transduction (Park et al., 2000). In C57BL/6 mice aged 6–8 weeks and injected with lentiviral vectors carrying the LacZ gene, there was a nearly 30-fold increase in X-Gal-positive hepatocytes in hepatectomized animals, compared with nonhepatectomized controls (Park et al., 2000). Similarly, the use of mitogenic compounds known to induce liver hyperplasia, such as 1,4-bis[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benzene (TCPOBOP), resulted in a 30-fold increase in hepatocyte transduction in young adult C57BL/6 mice (Ohashi et al., 2002). We have shown that phenobarbital, known as a weak inducer of hepatocyte proliferation, significantly increased hepatocyte transduction by 9-fold (Pichard et al., 2011). Finally, previous studies have revealed that lentiviral vector transduction efficiency was 10 times higher in young (3- to 4-week-old) and newborn rodents, in which the physiological turnover of hepatocytes is higher than in adult animals (Park et al., 2003; Nguyen et al., 2005, 2007). Therefore, although lentiviral transduction of hepatocytes is clearly improved by inducing liver regeneration by various stimuli, the actual relationship and kinetics between cell division and hepatocyte transduction remain ill-defined.

In the present study, we asked whether a complete cycle of cell division is required for optimal hepatocyte transduction in vivo. To answer this question, we used the antimitotic action of retrorsine, a member of the pyrrolizidine alkaloid family. In Fischer rats, administration of retrorsine after a regenerative stimulus such as partial hepatectomy or CCl4-induced liver injury results in inhibition of hepatocyte division (Laconi et al., 1999; Gordon et al., 2000a; Best and Coleman, 2010). Instead of hepatocyte mitotic figures, megalocytosis appears early in this setting (Laconi et al., 1999). Eventually, the liver mass is recovered through the emergence and expansion of a population of small hepatocyte-like progenitor cells (SHPCs) that progressively replaces megalocytic hepatocytes (Gordon et al., 2000b; Pichard and Ferry, 2008; Pichard et al., 2009). Megalocytosis, has long been thought to result from endoreplication of resident cells, which are able to undergo several rounds of DNA replication but cannot proceed through mitosis. Nuclear ploidy of up to 32n and 64n has been reported in rat liver exposed to retrorsine (White et al., 1973). Other studies showed that most megalocytes present in the liver of retrorsine-treated animals were unable to proceed through DNA synthesis (White et al., 1973; Laconi et al., 1999; Gordon et al., 2000a; Picard et al., 2003; Pitzalis et al., 2005). Although the exact mechanism of action of retrorsine remains unclear, these studies have shown that retrorsine inhibits hepatocyte division and induces blockade in interphase of the cell cycle (G1, S, and/or late G2).

In the present study, to better understand the relationship between lentiviral transduction efficiency and the cell cycle, hepatocytes were blocked in vivo in interphase of the cell cycle by retrorsine and then transduced by recombinant lentiviruses after (or not after) a partial hepatectomy to trigger cell division. We show that recombinant lentiviruses efficiently infected hepatocytes that gave rise to megalocytes, indicating that full mitosis is not necessary for lentiviral transduction of hepatocytes.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Fischer 344 rats were used in this study. All surgical procedures were conducted according to the guidelines of the French Ministère de l'Agriculture. Rats were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation (3%, v/v) and maintained under a 12-hr light–dark illumination cycle with food and water ad libitum. Hepatectomies were performed according to the procedure of Higgins and Anderson (1931).

Recombinant lentiviral vectors (4.3×109 transducing units [TU]/kg) and amphotropic MoMuLV recombinant retroviral vectors (3×109 TU/kg) were injected into the penile vein in a final volume of 3.2 ml.

Retrorsine was added to distilled water at 10 mg/ml and titrated to pH 2.5 with 1 N HCl to achieve complete dissolution. Subsequently, the solution was neutralized with 1 N NaOH, and NaCl was added to a final concentration of 6 mg/ml retrorsine and 0.15 mol/liter NaCl (pH 7). Retrorsine was administered by intraperitoneal injection.

Experimental design

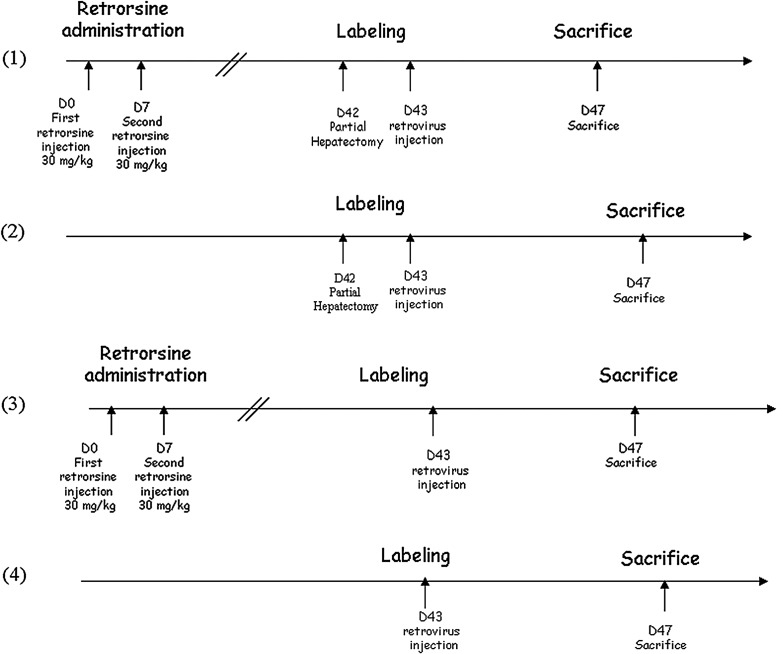

A first cohort of rats (group 1; n=4) aged 7 weeks received two doses of retrorsine 15 days apart. Five weeks after the second injection, rats were hepatectomized and 24 hr later they were injected intravenously with recombinant MoMuLV or lentiviral vectors. A second cohort of rats (group 2; n=4) aged 13 weeks received vectors 24 hr after a two-thirds partial hepatectomy without previous treatment with retrorsine. A third cohort of rats (group 3; n=4) was treated with retrorsine and 5 weeks after the second administration were injected with recombinant retroviral vectors but without partial hepatectomy. Finally, a cohort of control rats (group 4; n=4) aged 13 weeks was injected with vectors with no previous treatment. All rats were killed 4 days after retroviral injection. It is noteworthy (as shown in Fig. 1) that all animals received the viral vectors at the same age (13–14 weeks) to preclude any age-related variability of lentiviral vector transduction efficiency.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the experimental protocol, in which four groups of animals were used.

Lentiviral vectors

High-titer lentiviral vector stocks were generated by calcium phosphate-mediated transient transfection of 293T cells (2×108 cells) in 10-chamber Corning CellSTACK large culture vessels (Corning Life Sciences, Tewksbury, MA) with the recombinant vector plasmid, the packaging plasmid psPAX2, and the vesicular stomatitis virus G protein (VSV-G) envelope protein-coding plasmid pMD2G. Cells were transiently transfected at 70% confluence and, 24 hr after transfection, fresh medium containing 2 mM glutamine and antibiotics (penicillin, 100 IU/ml; streptomycin, 100 mg/ml) was added. Viral supernatant was collected at 24-hr intervals for two consecutive days. Viruses were concentrated by high-speed centrifugation in a JA-10 rotor (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) at 10,000 rpm for 16 hr at 4°C and the viral pellet was resuspended in culture medium. Concentrated vector aliquots were snap-frozen and stored at −80°C.

These vectors harbored the GFP gene under the control of a liver-specific murine transthyretin (mTTR) promoter formed with the mTTR promoter fused to a synthetic hepatocyte-specific enhancer. They contained four copies of a perfectly matched miR142-3p target sequence (kindly provided by L. Naldini, San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy, Milan, Italy) to decrease immune response (Brown et al., 2007; Schmitt et al., 2010). They also harbored the posttranscriptional regulatory element from the woodchuck hepatitis virus (WPRE), and a matrix attachment region to increase transgene expression.

To determine the titers of GFP-transducing vectors, serial dilutions of vector stock were used to transduce HeLa cells in 6-well plates. DNA was extracted and vector titers were determined by real-time quantitative PCR. Vector titers were routinely 5×109 TU/ml.

MoMuLV recombinant retroviral vectors

Amphotropic MoMuLV recombinant retroviral vectors contained the Escherichia coli nls-LacZ gene encoding β-galactosidase coupled to the nuclear localization signal from simian virus 40 (SV40) large T antigen was used (Cosset et al., 1995). Reporter gene transcription was under the control of the retroviral long terminal repeat (LTR). A 24-hr recombinant retroviral supernatant was harvested from confluent producer cells and filtered through a 0.45-μm (pore size) membrane. Titers were determined by end-point dilution, using Te671 target cells and counting of the resulting number of blue colonies after X-Gal staining. The titers obtained from the packaging cell lines were 108 transducing particles/ml.

Histological analysis and immunohistochemistry

Liver samples were formalin-fixed, embedded in paraffin, and cut in 5-μm sections. The presence of β-galactosidase- and GFP-positive hepatocytes was assessed by immunohistochemistry on formalin-fixed/paraffin-embedded sections, using anti-GFP (Clontech, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France) or anti-β-Gal antibodies (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA). Sections were dewaxed and rehydrated. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubation for 10 min in a 3% H2O2 solution in methyl alcohol. Blocking of nonspecific activity was carried out by incubation for 90 min in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Monoclonal primary rabbit anti-GFP antibody was applied for 2 hr at room temperature. Polyclonal primary mouse anti-β-Gal antibody was applied overnight. The dilutions were 1:200 for anti-GFP and 1:1000 for anti-β-Gal antibodies diluted in PBS containing 2% bovine serum albumin and 0.1% Tween 20. Positive cells were revealed with biotinylated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin and streptavidin–peroxidase, using diaminobenzidine as a substrate. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin.

The mitosis counts were assessed histologically after hematoxylin and eosin staining (Auvigne et al., 2002; Begay and Gandolfi, 2003).

The number of cells in metaphase and GFP- or β-Gal-positive cells were determined by random evaluation of 10 fields for nontreated animals and 30 fields for retrorsine-treated animals at ×40 magnification (corresponding approximately to 3000 hepatocytes).

In situ detection of ploidy

Three-micrometer-thick tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylene and after rehydration were boiled (three times, 5 min each) in citrate buffer (10 mmol/liter, pH 6.2) in a microwave oven. Immunohistochemistry was performed as described below. Plasma membranes were labeled with anti-β-catenin antibody (diluted 1:50; BD Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY). Hoechst 33342 (0.2 μg/ml) was used to stain and quantify DNA in each nucleus. Images were taken with an Eclipse E600 microscope with ×40 magnification, 1.4–0.7 NA Plan Apo objectives, a DXM1200 cooled CCD camera, and ACT-1 software (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Automatic quantitative image analysis was performed with IPLab Spectrum software (IPLab, Fairfax, VA). Nuclei were assigned as mono- or binucleated hepatocytes by comparing fluorescence and membrane labeling images. Other liver cell types (defined by their morphological characteristics), overlapping nuclei, and debris were eliminated interactively. Parameters such as integrated fluorescence intensity (IntF) were stored in computer files for analysis as described previously (Guidotti et al., 2003). A minimum of 300 hepatocytes was studied, observed on 8 to 12 separate fields; these observations concerned specimens from 4 animals for each point analyzed. This number of hepatocytes was within the range covered by other imaging-based studies.

Statistical analysis

All results were compared statistically by Mann–Whitney test, using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). p<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Cellular effects of retrorsine

In retrorsine-treated and hepatectomized rats (group 1), and in hepatectomized rats (group 2), liver histology was analyzed at the time of sacrifice. After hematoxylin–eosin staining of liver sections, we calculated a mitotic index of 0.02±0.001% in hepatectomized rats. No mitosis was recorded in retrorsine-treated and hepatectomized rats. Moreover, megalocytosis was clearly visible in group 1 animals whereas in liver sections from group 2 animals the size of hepatocytes was normal (Fig. 2A). We also analyzed ploidy in both groups of animals (Fig. 2B). In group 2 animals, hepatocyte nuclei were mainly tetraploid (53.9±2.9%) with a lower proportion of octaploid nuclei (6.5±3.6%). In contrast, in retrorsine-treated and hepatectomized rats, hepatocyte nuclei shifted to higher ploidy levels. Indeed, the percentage of octaploid nuclei was 24.3±0.8%, and 7.1±2.2% of the nuclei had a ploidy higher than 8C.

FIG. 2.

Liver cell polyploidization: A pivotal role for binuclear hepatocytes in retrorsine-treated/partially hepatectomized rats (group 1) and in partially hepatectomized rats (group 2). (A) Representative sections of group 1 and 2 animals 5 days after partially hepatectomy. Black arrows show the level of ploidy of hepatocytes. Hematoxylin and eosin (original magnification, ×400). (B) Evaluation of hepatocyte ploidy levels in groups 1 and 2 (n=4). Data are represented as means±SD. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare ploidy levels between groups 1 and 2. *The difference between two groups was considered to be significant when the p value was less than 0.05. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/hum

Analysis of lentiviral and oncoretroviral transduction

We next analyzed hepatocyte transduction in animals that were injected with recombinant MoMuLV vectors encoding β-galactosidase. In nonhepatectomized rats (groups 3 and 4), no cells expressing β-galactosidase were detected (Figs. 3A and 4A). In contrast, in hepatectomized rats (group 2), 6.8±1.3% of hepatocytes expressed the marker (Figs. 3A and 4B). This proportion of positive cells is in the range of the transduction level expected in this setting (Pichard et al., 2001, 2009). In retrorsine-treated and hepatectomized rats from group 1, only a small fraction of hepatocytes was transduced (0.62±0.1%) (Figs. 3A and 4C). Moreover, most of the transduced hepatocytes harboring a β-galactosidase-positive nucleus were small in size and few transduced megalocytes were recorded. Therefore we confirmed that full completion of mitosis is required to achieve efficient MoMuLV transduction as previously demonstrated. Finally, we analyzed transgene expression in animals that were injected with mTTR-GFP lentiviral vectors at a dose of 4.3×109 TU/kg. In nonhepatectomized rats (groups 3 and 4) no cells expressing GFP were detected (Figs. 3B and 4D). This confirmed that lentiviral vectors at low multiplicities of infection (MOIs) do not easily transduce differentiated adult hepatocytes that are in the G0 phase of the cell cycle. These results also showed that retrorsine per se did not improve lentiviral transduction in vivo. In contrast, in hepatectomized rats (group 2), 6.7±2.2% hepatocytes expressed GFP (Figs. 3B and 4E). This is in agreement with previous data from our laboratory (data not shown) and with previous studies showing that induction of cell proliferation by partial hepatectomy dramatically improved liver transduction (Park et al., 2000). More surprisingly, in retrorsine-treated and partially hepatectomized rats (group 1), we observed a significantly higher hepatocyte transduction efficiency (29.5±7.1%) (Figs. 3B and 4F).

FIG. 3.

Transduction efficacy in liver after injection of lentiviral vectors or oncoretroviral vectors in each group of rats (n=4). (A) Four days after oncoretrovirus injection, all rats were killed and the number of β-galactosidase-positive hepatocytes was scored on paraffin sections by immunohistochemistry. (B) All rats of each group received lentiviral vector encoding GFP and were killed on day 4 postinjection. The presence of GFP-positive hepatocytes in the liver was detected by immunohistochemistry. Data are represented as means±SD. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare levels of transduction between groups 1 and 2. *Significantly different (p<0.05).

FIG. 4.

Histochemical detection of transduced hepatocytes. (A–C) Representative sections from rats injected with oncoretroviral vectors encoding nuclear β-galactosidase are shown: (A) control (group 3); (B) partially hepatectomized rats (group 2); and (C) retrorsine-treated/partially hepatectomized rats (group 1). (D–F) Representative sections from rats injected with lentiviral vectors encoding GFP: (D) control (group 3); (E) partially hepatectomized rats (group 2); and (F) retrorsine-treated/partially hepatectomized rats (group 1). All sections were hematoxylin counterstained. All original magnifications: ×200.

To obtain further insight in the relationship between ploidy and lentiviral vector transduction, we analyzed ploidy of GFP expressing hepatocytes. First, we measured the percentage of binucleated hepatocytes in hepatectomized rats treated or not with retrorsine. Binucleated cell contingent are generated in the liver parenchyma during postnatal liver development due to incomplete cytokinesis (Margall-Ducos et al., 2007). We observed that the percentage of binucleated hepatocytes is not significantly different between the two groups (group 1, 5.5±1.4%; group 2, 4.3±1.9%). In nonhepatectomized rats, the rate of binucleation is 26.4±2.5%. As already observed by other groups, binucleated fraction is low in hepatectomized rodents. During regenerative process, growth pattern is switched to a nonbinucleating mode of growth (Celton-Morizur and Desdouets, 2010). We next analyzed nuclear ploidy profile. Nuclei area of transduced hepatocytes was calculated in animals from groups 1 and 2. Area and nuclei ploidy of transduced hepatocytes were calculated in animals from group 1 and 2. As shown in Fig. 5, in hepatectomized rat (group 2), GFP-positive hepatocytes had the same ploidy pattern than nonlabeled hepatocytes: 38% of GFP-positive hepatocytes had diploid nuclei and 56% tetraploid nuclei. In contrast in retrorsine-treated and hepatectomized rats (group 1), ploidy pattern of GFP-positive hepatocytes differed from that of nonlabeled hepatocytes. More than 70% of GFP-positive hepatocytes have ploidy equal to or greater than 8C. In contrast, diploid nuclei were poorly transduced (2.5%).

FIG. 5.

Analysis of the ploidy of GFP-expressing hepatocytes in retrorsine-treated/partially hepatectomized rats (group 1) and partially hepatectomized rats (group 2). (A) Image of a liver section after double staining with Hoechst (nuclear labeling, green) and GFP fluorescence (cytoplasmic labeling, red). Area of each transduced hepatocyte was calculated. (B) Evaluation of GFP-expressing hepatocyte ploidy levels in each group of rats (n=3). Data are represented as means±SD. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the ploidy of GFP-expressing hepatocytes between groups 1 and 2. *Significantly different (p<0.05).

Discussion

Many previous publications have shown that induction of cell proliferation either after partial hepatectomy or after mitogenic compounds administration, dramatically improved liver lentiviral transduction (Park et al., 2000; Ohashi et al., 2002). However, in contrast to murine oncoretroviral vectors, it is still not clear whether passage of the cell through mitosis is required to achieve such improvement. In the present study we used the antimitotic effect of retrorsine to get further insight in this issue.

Partial hepatectomy alone resulted in a similar increase in hepatocyte transduction when using either the lentiviral or MoMuLV vector. Indeed, no positive cells were recorded in the absence of partial hepatectomy whereas 6.8 and 6.7% β-galactosidase- or GFP-expressing cells were counted after partial hepatectomy and injection of MoMuLV or lentiviral vector, respectively. Although two different cassettes were present in the two vector types, we believe that the similar transduction levels indicate that after partial hepatectomy the limiting factor for retroviral transduction is the number of dividing cells at the time of vector injection. Surprisingly, administration of retrorsine before partial hepatectomy resulted in opposite effects on MoMuLV and lentiviral vector transduction. Indeed, MoMuLV transduction was decreased 10-fold (0.6 vs. 6.8% positive cells) whereas lentiviral transduction increased 4-fold (29 vs. 6.7% positive cells). It is important to note that the same batches of lentiviral or MoMuLV vector were used throughout the study. Therefore the differences observed cannot be ascribed to batch-to-batch variability of any of these vectors.

Retrorsine is known to block mitosis in hepatocytes (Gordon et al., 2000a). Because MoMuLV transduction is dependent mainly on mitosis, it is therefore not surprising that retrorsine treatment also directly impaired MoMuLV transduction. In contrast, the strong positive effect of retrorsine on lentiviral transduction was not expected. Indeed, although mitosis is not compulsory for efficient lentiviral transduction, it can enhance the number of transduced cells as evidenced after partial hepatectomy. Therefore, we would have expected a similar enhancement of lentiviral transduction in both the absence and presence of retrorsine treatment as compared with nonhepatectomized animals. Because retrorsine alone had no effect on hepatocyte transduction, we believe that polyploidization (and hence DNA synthesis) is responsible for the increase in liver transduction between hepatectomized and retrorsine-treated and hepatectomized animals. Indeed, when retrorsine was administered before partial hepatectomy, we observed an acute increase in polyploidy that was correlated with megalocytosis, consistent with previous studies in rats (Sigal et al., 1999). This pattern is typical of the antimitotic action of the pyrrolizidine alkaloid and of its metabolites on hepatocytes.

The exact mode of action of retrorsine is not yet fully understood. It has been postulated that the appearance of megalocytes with a significantly higher ploidy after retrorsine treatment and liver damage resulted from a block in the late S/G2 phase of the cell cycle (Samuel and Jago, 1975). However, other studies suggested that hepatocytes are blocked in G1/S after retrorsine treatment (Laconi et al., 1999; Picard et al., 2003). In these latter studies DNA synthesis and bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) labeling were decreased in rats treated with retrorsine. However, the authors admitted that a subpopulation of megalocytes was able to undergo repeated cycles of DNA synthesis because they have significantly higher ploidy. Interestingly, immunohistochemical studies showed that a large proportion of megalocytes exposed to retrorsine overexpressed cyclin D1 (Pitzalis et al., 2005). Cyclins D1 and D3 have a key role in promoting endomitosis (Zimmet et al., 1997). Therefore we believe that hepatocytes undergoing endoreplication are the actual target population for lentiviral transduction and that endoreplication is a facilitating factor for lentiviral transduction. More than 70% of GFP-positive hepatocytes had ploidy equal to or greater than 8C; in contrast, only 2.5% of diploid nuclei were transduced. Our results are in agreement with previous studies of the replication of HIV or lentiviral transduction in vitro (Groschel and Bushman, 2005; Zhang et al., 2006). Groschel and Bushman have shown that blocking embryonic kidney cells (293T) in the G1 phase resulted in a significant improvement in cell transduction with HIV (Groschel and Bushman, 2005). They showed that the arrest of cells in the G2 phase caused a similar effect but at a higher degree. Moreover, during wild-type HIV infection, it was shown that Vpr, an accessory protein, caused the arrest of cells in G2 to increase viral replication (He et al., 1995; Zhou and Ratner, 2000). Finally, the important role of the G2 phase in HIV-1 replication extends to third-generation lentiviral vectors. Indeed, Zhang and colleagues have shown that blocking of several cell types in vitro in the G2 phase of the cell cycle after genistein treatment significantly enhanced lentiviral recombinant transduction (Zhang et al., 2006). Overall, these studies showed that progression in the cell cycle up to the G2 phase is important for HIV replication or for transduction by a recombinant lentivirus.

In conclusion, our study shows that lentiviral vectors do not easily transduce G0-arrested hepatic cells. However lentiviral transduction can be enhanced in vivo through endoreplication. Therefore we believe that the use of agents able to induce cell cycle arrest may represent a potential strategy to improve gene transfer in the liver.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Association Française contre les Myopathies. The authors thank Tuan Huy Nguyen (U948 Nantes) and Sébastien Boni (U948 Nantes) for providing the lentiviral vector stocks.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Auvigne I. Pichard V. Aubert D., et al. In vivo cell lineage analysis in cyproterone acetate-treated rat liver using genetic labeling of hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2002;35:281–288. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.30696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begay C.K. Gandolfi A.J. Late administration of COX-2 inhibitors minimize hepatic necrosis in chloroform induced liver injury. Toxicology. 2003;185:79–87. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00594-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best D.H. Coleman W.B. Liver regeneration by small hepatocyte-like progenitor cells after necrotic injury by carbon tetrachloride in retrorsine-exposed rats. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2010;89:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown B.D. Gentner B. Cantore A., et al. Endogenous microRNA can be broadly exploited to regulate transgene expression according to tissue, lineage and differentiation state. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:1457–1467. doi: 10.1038/nbt1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celton-Morizur S. Desdouets C. Polyploidization of liver cells. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010;676:123–135. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6199-0_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosset F.L. Takeuchi Y. Battini J.L., et al. High-titer packaging cells producing recombinant retroviruses resistant to human serum. J. Virol. 1995;69:7430–7436. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7430-7436.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon G.J. Coleman W.B. Grisham J.W. Temporal analysis of hepatocyte differentiation by small hepatocyte-like progenitor cells during liver regeneration in retrorsine-exposed rats. Am. J. Pathol. 2000a;157:771–786. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64591-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon G.J. Coleman W.B. Hixson D.C. Grisham J.W. Liver regeneration in rats with retrorsine-induced hepatocellular injury proceeds through a novel cellular response. Am. J. Pathol. 2000b;156:607–619. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64765-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groschel B. Bushman F. Cell cycle arrest in G2/M promotes early steps of infection by human immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 2005;79:5695–5704. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5695-5704.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti J.E. Brégerie O. Robert A., et al. Liver cell polyploidization: A pivotal role for binuclear hepatocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:19095–19101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300982200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J. Choe S. Walker R., et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viral protein R (Vpr) arrests cells in the G2 phase of the cell cycle by inhibiting p34cdc2 activity. J. Virol. 1995;69:6705–6711. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6705-6711.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins G.M. Anderson R.M. Experimental pathology of the liver. I. Restoration of the liver of the white rat following partial surgical removal. Arch. Pathol. 1931;12:186–202. [Google Scholar]

- Kootstra N.A. Zwart B.M. Schuitemaker H. Diminished human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcription and nuclear transport in primary macrophages arrested in early G1 phase of the cell cycle. J. Virol. 2000;74:1712–1717. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.4.1712-1717.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laconi S. Curreli F. Diana S., et al. Liver regeneration in response to partial hepatectomy in rats treated with retrorsine: A kinetic study. J. Hepatol. 1999;31:1069–1074. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80320-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margall-Ducos G. Celton-Morizur S. Couton D., et al. Liver tetraploidization is controlled by a new process of incomplete cytokinesis. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120:3633–3639. doi: 10.1242/jcs.016907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naldini L. Blömer U. Gallay P., et al. In vivo gene delivery and stable transduction of nondividing cells by a lentiviral vector. Science. 1996;272:263–267. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T.H. Bellodi-Privato M. Aubert D., et al. Therapeutic lentivirus-mediated neonatal in vivo gene therapy in hyperbilirubinemic Gunn rats. Mol. Ther. 2005;12:852–859. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.06.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T.H. Aubert D. Bellodi-Privato M., et al. Critical assessment of lifelong phenotype correction in hyperbilirubinemic Gunn rats after retroviral mediated gene transfer. Gene Ther. 2007;14:1270–1277. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi K. Park F. Kay M.A. Role of hepatocyte direct hyperplasia in lentivirus-mediated liver transduction in vivo. Hum. Gene Ther. 2002;13:653–663. doi: 10.1089/10430340252837242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park F. Ohashi K. Chiu W., et al. Efficient lentiviral transduction of liver requires cell cycling in vivo. Nat. Genet. 2000;24:49–52. doi: 10.1038/71673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park F. Ohashi K. Kay M.A. The effect of age on hepatic gene transfer with self-inactivating lentiviral vectors in vivo. Mol. Ther. 2003;8:314–323. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard C. Lambotte L. Starkel P., et al. Retrorsine: A kinetic study of its influence on rat liver regeneration in the portal branch ligation model. J. Hepatol. 2003;39:99–105. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichard V. Ferry N. Origin of small hepatocyte-like progenitor in retrorsine-treated rats. J. Hepatol. 2008;48:368–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichard V. Aubert D. Ferry N. Efficient retroviral gene transfer to the liver in vivo using nonpolypeptidic mitogens. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;286:929–935. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichard V. Aubert D. Ferry N. Direct in vivo cell lineage analysis in the retrorsine and 2AAF models of liver injury after genetic labeling in adult and newborn rats. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichard V. Boni S. Baron W., et al. Priming of hepatocytes enhances in vivo liver transduction with lentiviral vectors in adult mice. Hum. Gene Ther. 2012;23:8–17. doi: 10.1089/hgtb.2011.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitzalis S. Doratiotto S. Greco M., et al. Cyclin D1 is up-regulated in hepatocytes in vivo following cell-cycle block induced by retrorsine. J. Hepatol. 2005;43:485–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel A. Jago M.V. Localization in the cell cycle of the antimitotic action of the pyrrolizidine alkaloid, lasiocarpine and of its metabolite, dehydroheliotridine. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1975;10:185–197. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(75)90112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt F. Remy S. Dariel A., et al. Lentiviral vectors that express UGT1A1 in liver and contain miR-142 target sequences normalize hyperbilirubinemia in Gunn rats. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:999–1007. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.008. 1007.e1001–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigal S.H. Rajvanshi P. Gorla G.R., et al. Partial hepatectomy-induced polyploidy attenuates hepatocyte replication and activates cell aging events. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;276:G1260–G1272. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.5.G1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White I.N. Mattocks A.R. Butler W.H. The conversion of the pyrrolizidine alkaloid retrorsine to pyrrolic derivatives in vivo and in vitro and its acute toxicity to various animal species. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1973;6:207–218. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(73)90048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zack J.A. Arrigo S.J. Weitsman S.R., et al. HIV-1 entry into quiescent primary lymphocytes: Molecular analysis reveals a labile, latent viral structure. Cell. 1990;61:213–222. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90802-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S. Joseph G. Pollok K., et al. G2 cell cycle arrest and cyclophilin A in lentiviral gene transfer. Mol. Ther. 2006;14:546–554. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y. Ratner L. Phosphorylation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr regulates cell cycle arrest. J. Virol. 2000;74:6520–6527. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.14.6520-6527.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmet J.M. Ladd D. Jackson C.W., et al. A role for cyclin D3 in the endomitotic cell cycle. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:7248–7259. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.7248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zufferey R. Nagy D. Mandel R.J., et al. Multiply attenuated lentiviral vector achieves efficient gene delivery in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 1997;15:871–875. doi: 10.1038/nbt0997-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]