Abstract

Tuberculous uveitis is an underdiagnosed form of uveitis. Absence of pulmonary signs and symptoms does not rule out the disease. In an era of reduced immunity from human immunodeficiency virus and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, the disease is becoming more prevalent. This review discusses the common manifestations of tuberculous uveitis, pointing out helpful diagnostic criteria in suspicious cases of uveitis. Physicians need to be aware that ocular manifestations of tuberculosis may be independent of systemic disease.

Keywords: tuberculous uveitis, ocular manifestations, tuberculosis

Introduction

Tuberculosis is a chronic bacterial infection caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis.1 It affects about a third of the world population, with Nigeria, India, China, Pakistan, Indonesia, Bangladesh, and South Africa contributing about 80% of the burden.2 Extrapulmonary tuberculosis, including tuberculosis of the eye, is reemerging as a major challenge all across the globe.3

Tuberculosis is acquired by droplet infection. The organism gets lodged in the alveoli where epitheloid cells of the immune response may contain it in resistant hosts. It can gain access to lymphatics and blood vessels and become disseminated to distant sites such as the eyes. Reactivation of the dormant organism is a common cause of infection in adults.

Anterior segment manifestations of tuberculosis include lid vulgaris, conjunctivitis, scleritis, episcleritis, corneal phlycten, interstitial keratitis, and granulomatous uveitis. Other manifestations include orbital granuloma, panophthalmitis, and optic nerve involvement. Intracranial involvement may lead to meningitis, cranial nerve palsies, and raised intracranial pressure.

Tuberculous uveitis

Tuberculosis is an underdiagnosed etiological agent in uveitis.4 Anterior tuberculous uveitis is granulomatous, and the diagnosis should be considered in all cases of chronic granulomatous anterior uveitis. The absence of clinically evident pulmonary tuberculosis does not rule out the possibility of ocular tuberculosis, because approximately 60% of patients with extrapulmonary tuberculosis have no evidence of pulmonary tuberculosis.5

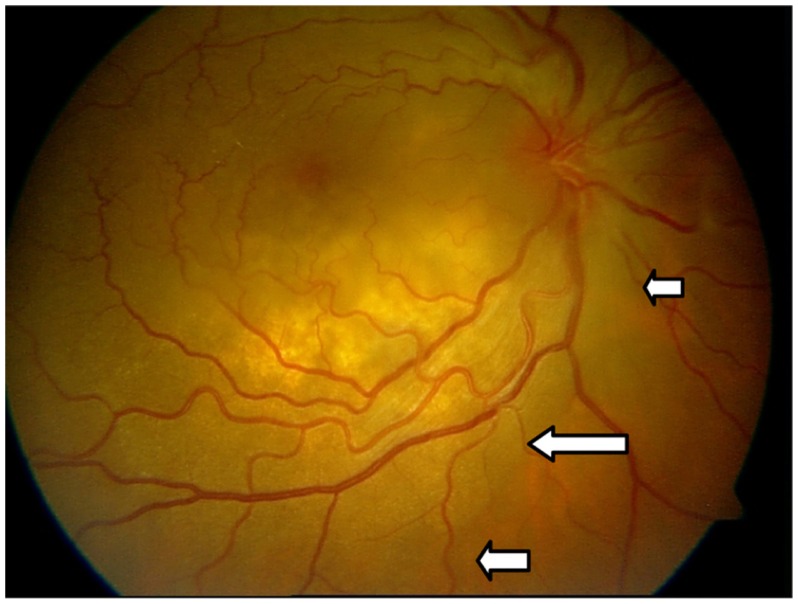

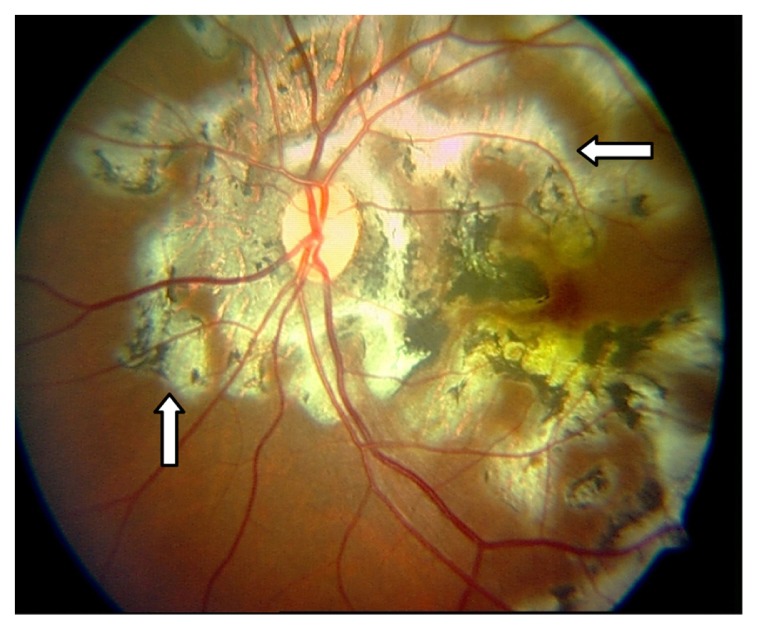

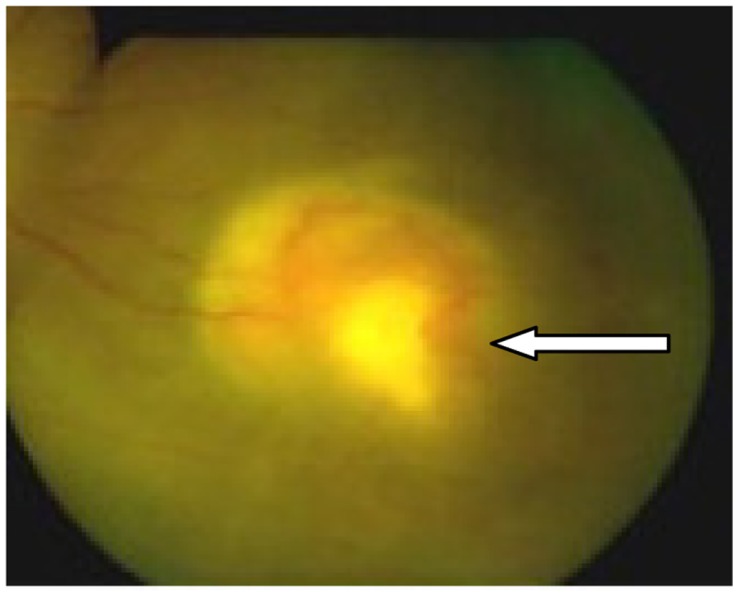

The common manifestations of tuberculous uveitis include a choroidal mass with or without obvious inflammatory signs (34%), choroiditis/chorioretinitis (27%), vitritis (24%), iridocyclitis/anterior chamber reaction (13%), and panophthalmitis (11%). Other findings include solitary choroidal granuloma or tuberculoma (Figure 1), multifocal choroidal tubercles, endophthalmitis, serpiginous-like choroiditis (Figure 2), subretinal abscess (Figure 3), neuroretinitis, and retinal vasculitis.6

Figure 1.

Choroidal granuloma presenting as a subretinal mass with disc involvement in a 45-year-old woman (arrows showing edge of mass).

Photograph courtesy of Dhanjay Shukla.

Figure 2.

Serpiginous choroidopathy with snake-like chorioretinal involvement (arrows) in a 45-year-old man.

Photograph courtesy of Dhanjay Shukla.

Figure 3.

Subretinal abscess (arrow) in an immunocompromised 27-year-old woman with tuberculosis on highly active antiretroviral therapy.

Differential diagnosis

Patients with tuberculous uveitis present with chronic granulomatous uveitis. Most cases will be bilateral. Uveitis from toxoplasmosis is usually a unilateral disease with a characteristic active retinitis adjacent to an old scar. In immunocompromised patients, toxoplasmosis may present without the characteristic scar, making it a close differential diagnosis. A good history taken from a patient with suspected tuberculous uveitis may reveal previous contact with a person or persons with a chronic cough. A Mantoux test may be positive.

Sarcoidosis, a cause of chronic granulomatous uveitis, is a multisystemic disease and a close differential diagnosis. Presentation may be bilateral, with associated respiratory symptoms and signs. A chest X-ray is usually suggestive of the disease. Pointers to tuberculous uveitis include bilaterality, broad-based posterior synechiae, retinal vasculitis with or without choroiditis, and serpiginous-like choroiditis in patients with latent or manifest tuberculosis in tuberculosis-endemic areas.7 Other considerations include presence of multifocal choroidal tubercles and subretinal abscess. A multidisciplinary approach to management is warranted.

A combination of anterior uveitis signs, posterior synechiae, vitritis and retinal vasculitis with a positive mantoux test or demonstration of acid fast bacilli on ocular fluid with or without a therapeutic test of Izoniacid is highly suggestive of ocular tuberculosis.7

Abrams and Schlaegel reported that, of 18 patients with presumed tubercular uveitis, the chest X-ray showed no active or inactive evidence of tuberculosis in 17 cases, and that only nine patients had at least 5 mm of induration when evaluated with an intermediate-strength purified protein derivative test (5 tuberculin units), with five experiencing no reactivity.8 The isoniazid therapeutic test consists of isoniazid 300 mg/day for 3 weeks. A result is considered positive if there is dramatic improvement after 1–3 weeks of therapy. False negative results occur in the presence of drug resistance and in overwhelming human immunodeficiency virus infection.8

Treatment of tubercular uveitis

An infectious diseases consultation is mandatory. Multidrug treatment with pyrazinamide, ethambutol, isoniazid, and rifampin is recommended. The first two agents are stopped after 2–3 months, and treatment is continued for a further 9–12 months with isoniazid and rifampin.9 Response to treatment is evident within 2–4 weeks. Low-dose steroids for 4–6 weeks, concomitant with multidrug antituberculosis chemotherapy, may limit damage to ocular tissues from a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction. Topical steroids and cycloplegics should be given as treatment for anterior uveitis.

Conclusion

A high index of suspicion is needed in the diagnosis of tuberculous uveitis. Immunocompromised patients, malnourished children, and debilitated patients are at risk. A chest X-ray, Mantoux test, and clinical examination may be negative for tuberculosis. A therapeutic trial of isoniazid should be considered in suspicious cases. A multidisciplinary approach to management is advocated.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The author reports no conflict of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Case definitions for infectious conditions under public health surveillance. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1997;46:40–41. [No authors listed] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dye C, Scheele S, Dolin P, et al. Global burden of tuberculosis: estimated incidence, prevalence, and mortality by country. JAMA. 1999;282:667–686. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.7.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported Tuberculosis in the United States. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2002. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varma D, Anand S, Reddy AR, et al. Tuberculosis: an under-diagnosed aetiological agent in uveitis with an effective treatment. Eye. 2006;20:1068–1073. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alvarez S, McCabe WR. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis revisited: a review of experience at Boston City and other hospitals. Medicine (Baltimore) 1984;63:25–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demirici H, Shields CL, Shields JA, et al. Ocular tuberculosis masquerading as ocular tumors. Surv Ophthalmol. 2004;49:78–89. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta A, Bansal R, Gupta V, et al. Ocular signs predictive of tubercular uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149:562–570. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abrams J, Schlaegel TF. The role of the isoniazid therapeutic test in tuberculosis uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982;94:511–515. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(82)90245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patterson PE, Kimerling ME, Bailey WC, et al. Chemotherapy of tuberculosis. In: Schlossberg D, editor. Tuberculous and Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1999. [Google Scholar]