Abstract

The discovery in archaea of an alternative proteasome based on Cdc48 provides insights into theevolution of protein degradation machines.

Selective protein degradation in eukaryote is mediated primarily by the ubiquitin-proteasome system, in which the small protein ubiquitin is covalently attached to a target protein to signal its degradation by the 26S proteasome (1). The ubiquitin-proteasome system may include as many as1000 distinct gene products, thus constituting one of the broadest regulatory systems in nature. Recent work, including a report by Barthelme and Sauer on page 843 of this issue (2), has shed light on how this baroque pathway may have evolved and raises some unexpected possibilities for the mechanism by which proteins are delivered to proteasomes for their destruction.

Although no prokaryote has a bona fide version of the eukaryotic ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, various archaea and bacteria contain adenosine triphosphate (ATP)–dependent proteases that are of the same basic design (3, 4). For example, many archaea have a proteasome-like complex known as PAN (3, 4). PAN is composed of a hollow, 28-subunit proteolytic core particle (the 20S core particle), in which proteins are degraded, and a 6-subunit adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) complex (the PAN cap). The PAN cap activates the core particle by opening up a channel and translocating in substrates while unfolding their globular domains. Ancestral variants of ubiquitin are also found in archaea, although the most prominent of these are not used to tag proteins for degradation (5). Nonetheless, ubiquitination-like protein conjugation systems linked to protein degradation have been found in archaea and some bacteria (6, 7).

Among the curiosities of the eukaryotic ubiquitin-proteasome system is an ATPase complex known as Cdc48 (sometimes called p97 or VCP) (8). Its subunits form a six-membered ring, similar to the proteasomal ATPases, but their amino acid sequences are only distantly related. Cdc48 is involved in a range of cellular functions that involve ubiquitin but not always protein degradation. Mechanistically, Cdc48 appears to work in two different modes. One is to serve as a ubiquitin chain editing platform by interacting with factors that recognize ubiquitinated substrates, and with enzymes that add or remove ubiquitin (8, 9). The other is to extract ubiquitinated proteins from membranes or complex structures such as chromatin and deliver them to proteasomes in the cytosol (8,10,11). Thus, Cdc48 seems to prepare substrates for the proteasome in various ways—handing them to the proteasome's ATPase caps (called 19S caps in eukaryotes), which then feed them into the proteolytic core. Oddly, the 19S caps (1) have functions similar to Cdc48. They also bind to ubiquitin and to enzymes that add or remove ubiquitin, and they can unfold stable proteins and disassemble complexes (12). Could a substrate bypass the 19S caps on the way to degradation?

The C terminus of Cdc48 contains the distinctive HbYX motif (2), which had been identified in archaeal PAN (3) and was shown to mediate PAN's binding to the core particle. The motif is also highly conserved in the eukaryotic 19S caps (2,3), where it again mediates interaction with the core particle. Thus, its appearance also in Cdc48 has been a persistent mystery. To address this, Barthelme and Sauer astutely focused on archaea rather than eukaryotes. They noticed that the core particle is found in all archaea but that PAN is missing in some, which suggested the presence of an unidentified ATPase cap. Given the HbYX motifs of Cdc48, they tested whether archaeal Cdc48 could be this missing cap. Indeed, archaeal Cdc48 bound the core particle, predominantly through the HbYX motif, and was capable of injecting substrates into the core particle cavity.

What do these findings tell us about the origin of the eukaryotic protein degradation system and its overall design? There are two principal interpretations (see the figure). The more conservative model 1 posits that in archaea, PAN and Cdc48 function in parallel as core particle activators. As the eukaryotic system evolved, Cdc48 was pushed aside to function upstream of the proteasome rather than as a part of it, and no longer docks onto the core particle. In this model, Cdc48 became deeply entrenched in the ubiquitin pathway even as it lost its direct connection to the core particle, as evidenced by its association with a large number of ubiquitin receptors that bring substrates to it (8, 13). Also, many proteins require Cdc48 for degradation (8). This model fails to account for the conservation of Cdc48's HbYX motifs in eukaryotes, although there may be alternative explanations for this (14, 15). Moreover, it is puzzling that an enzyme complex pre-adapted to degrade ubiquitin conjugates in the eukaryotic lineage would have been passed over for this role. A possible rationale would be that, as Cdc48 evolved into a broadly acting factor for extracting proteins from membranes and complexes, tight coupling to the core particle and thus degradation became a liability.

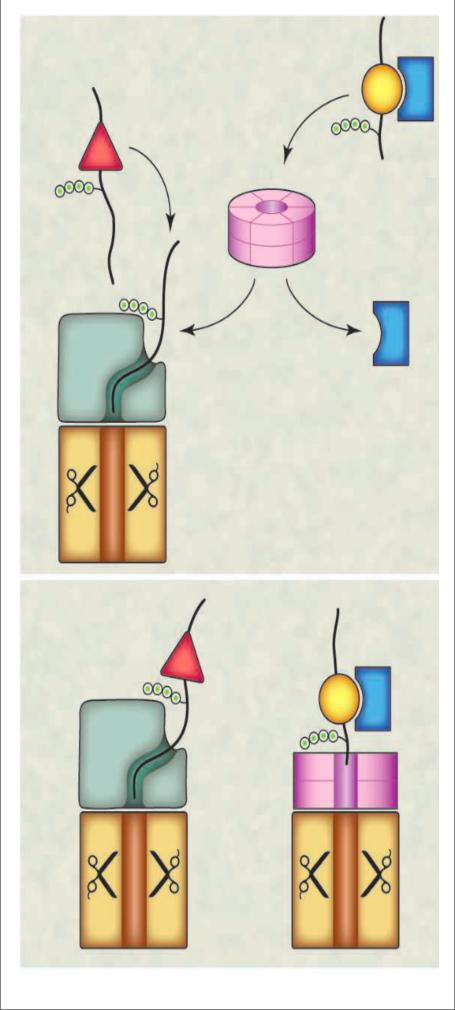

Figure. Two models of eukaryotic Cdc48 action.

(A) In model 1, Cdc48 has lost its ancient ability to interact directly with the core particle and functions as an accessory factor to deliver substrates to the 26S proteasome, which contains its own 19S caps. Cdc48 can disassemble protein complexes and serve as a ubiquitin editing platform.

(B) In model 2, Cdc48 retains its ability to associate with the proteasome core particle, and this allows two types of activated proteasome complexes with distinct ATPase caps to form. The different caps may be optimized for different subsets of proteasome substrates. Substrate interaction with the two proteasome particles in both models can be mediated by adaptors, which are not shown in the figure.

Model 2 asserts that Cdc48 functions similarly in both eukaryotes and archaea. Thus, in eukaryotes, the 19S cap and Cdc48 work in parallel to deliver substrates to the proteolytic core particle. This has good logic but conflicts with the long-standing paradigm of Cdc48 working upstream of the fully assembled proteasome (8). First, no eukaryotic Cdc48–core particle complex has ever been isolated or successfully reconstituted in eukaryotes, and not for a lack of trying. To identify an interaction between Cdc48 and the core particle in archaea, Barthelme and Sauer used an ATPase-defective mutant of Cdc48 because ATP hydrolysis weakens contacts at the Cdc48–core particle interface. Thus, the same trick may be necessary to detect an interaction in the eukaryotic system. The eukaryotic 26S proteasome is quite stable, but there is ample precedent for instability of activator–core particle complexes in bacteria. The second caveat is that, to our knowledge, no protein has been reported to require Cdc48 but not the 19S cap for proteasomal degradation. However, surprisingly few substrates have been tested for this (11), and perhaps the right proteins have not yet been examined.

If the 19S and Cdc48 caps both recognize substrates through ubiquitin, how might their functions differ? One possibility is that the Cdc48 and 19S caps unfold proteins by different mechanisms, such that each cap is best suited to unfolding a distinct subset of protein folds. Alternatively, the difference could lie in the step that follows the first recognition as the proteasome engages its substrates at initiation sequences. For example, in the 19S caps, the entrance to the degradation channel is somewhat occluded (16) so that it might be inaccessible to some sequences (17).

The potential new function of Cdc48 as a proteasome component would provide Cdc48 with a clearer role in the ubiquitin pathway and tighten the pathway's overall design. However, conceptual neatness has never been a good predictor of biology.

References

- 1.Finley D. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009;78:477. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.081507.101607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barthelme D, Sauer RT. Science. 2012;337:843. doi: 10.1126/science.1224352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith DM, et al. Mol. Cell. 2007;27:731. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang F, et al. Mol. Cell. 2009;34:473. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burroughs AM, Iyer LM, Aravind L. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012;832:15. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-474-2_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pearce MJ, Mintseris J, Ferreyra J, Gygi SP, Darwin KH. Science. 2008;322:1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1163885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Humbard MA, et al. Nature. 2010;463:54. doi: 10.1038/nature08659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer H, Bug M, Bremer S. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012;14:117. doi: 10.1038/ncb2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richly H, et al. Cell. 2005;120:73. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ye Y, Meyer HH, Rapoport TA. Nature. 2001;414:652. doi: 10.1038/414652a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jarosch E, et al. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002;4:134. doi: 10.1038/ncb746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verma R, McDonald H, Yates JR, 3rd, Deshaies RJ. Mol. Cell. 2001;8:439. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00308-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexandru G, et al. Cell. 2008;134:804. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao G, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:8785. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Böhm S, Lamberti G, Fernández-Sáiz V, Stapf C, Buchberger A. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2011;31:1528. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00962-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lander GC, et al. Nature. 2012;482:186. doi: 10.1038/nature10774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beskow A, et al. J. Mol. Biol. 2009;394:732. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]