Background: An ELISA was developed to determine the role of apoE/Aβ on soluble Aβ accumulation.

Results: In AD transgenic mouse brain and human synaptosomes and CSF, levels of soluble apoE/Aβ are lower and oligomeric Aβ levels are higher with APOE4 and AD.

Conclusion: Isoform-specific apoE/Aβ levels modulate soluble oligomeric Aβ levels.

Significance: ApoE/Aβ and oligomeric Aβ represent a mechanistic approach to AD biomarkers.

Keywords: Alzheimer Disease, Apolipoprotein Genes, Biomarkers, Protein Complexes, Synaptosomes, Biomarker, Amyloid-β, ApoE/Aβ Complex, Apolipoprotein E, Oligomeric Aβ

Abstract

Human apolipoprotein E (apoE) isoforms may differentially modulate amyloid-β (Aβ) levels. Evidence suggests physical interactions between apoE and Aβ are partially responsible for these functional effects. However, the apoE/Aβ complex is not a single static structure; rather, it is defined by detection methods. Thus, literature results are inconsistent and difficult to interpret. An ELISA was developed to measure soluble apoE/Aβ in a single, quantitative method and was used to address the hypothesis that reduced levels of soluble apoE/Aβ and an increase in soluble Aβ, specifically oligomeric Aβ (oAβ), are associated with APOE4 and AD. Previously, soluble Aβ42 and oAβ levels were greater with APOE4 compared with APOE2/APOE3 in hippocampal homogenates from EFAD transgenic mice (expressing five familial AD mutations and human apoE isoforms). In this study, soluble apoE/Aβ levels were lower in E4FAD mice compared with E2FAD and E3FAD mice, thus providing evidence that apoE/Aβ levels isoform-specifically modulate soluble oAβ clearance. Similar results were observed in soluble preparations of human cortical synaptosomes; apoE/Aβ levels were lower in AD patients compared with controls and lower with APOE4 in the AD cohort. In human CSF, apoE/Aβ levels were also lower in AD patients and with APOE4 in the AD cohort. Importantly, although total Aβ42 levels decreased in AD patients compared with controls, oAβ levels increased and were greater with APOE4 in the AD cohort. Overall, apoE isoform-specific formation of soluble apoE/Aβ modulates oAβ levels, suggesting a basis for APOE4-induced AD risk and a mechanistic approach to AD biomarkers.

Introduction

APOE4 is the primary genetic risk factor for Alzheimer disease (AD),5 although APOE2 reduces risk compared with APOE3. Although the mechanism(s) by which apolipoprotein E (apoE) and amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) affect the pathogenesis of AD remains unclear (1, 2), apoE isoform-specific physical interactions with Aβ (apoE/Aβ) may modulate the levels of Aβ. These interactions appear to consist of two types, which may or may not be “on pathway” to amyloid deposition as follows: apoE isoform-specific effects on plaque development and apoE isoform-specific effects on the levels of soluble, oligomeric aggregates of Aβ (oAβ). For this study, an apoE/Aβ ELISA was developed to determine the effect of the APOE genotype on the levels of soluble apoE/Aβ and Aβ.

The amyloid hypothesis posits that deposition of extracellular amyloid is central for producing the neurodegenerative processes characteristic of AD (3). In the landmark 1992 paper, Wisniewski and Frangione (4) proposed that apoE was a “pathological chaperone,” based on the co-localization of apoE with Aβ in amyloid plaques as detected via immunohistochemistry (IHC). Thus, apoE was thought to facilitate the process of Aβ deposition as amyloid. Biochemical analyses validate IHC measures, as the levels of apoE and Aβ are equivalent in the insoluble extraction fraction from brains of transgenic mice expressing familial AD (FAD) mutations (FAD-Tg), specifically the 5×FAD-Tg mice (5). The association of APOE4 with AD risk was first described in 1993 (6, 7), leading to research efforts focused on the effects of the APOE genotype on plaque burden and the structural relationship between apoE and amyloid. IHC analysis demonstrates that plaque deposition is greater with APOE4 compared with APOE3 in AD and nondemented controls (8, 9) and that a higher proportion of Aβ within a plaque is associated with apoE4 than with apoE3 (10). Biochemical analysis confirms that the levels of apoE and Aβ are also higher with APOE4 compared with APOE3 in the insoluble extraction fraction from brains of FAD-Tg mice (11). Thus, APOE4 not only facilitates amyloid deposition but also forms a greater amount and/or more stable form of apoE4/amyloid than apoE3/amyloid.

The amyloid hypothesis has been revised, as plaque burden does not correlate with the dementia that is characteristic of AD (12, 13). However, soluble Aβ and oAβ do correlate with cognitive decline and disease severity in humans (14). oAβ is also detected in FAD-Tg mice and is associated with memory decline (14). Thus, the structure-function relationship of soluble Aβ and oAβ is an area of intense research. However, unlike amyloid, which refers to a specific parallel β-sheet structure, oAβ refers to a number of assemblies defined by a variety of detection methods (14). This makes interpretation and comparison of results problematic, particularly with in vivo data. We recently developed an oAβ ELISA and demonstrated that in EFAD-Tg mice soluble Aβ42 and oAβ are greater in E4FAD mice, compared with E2FAD and E3FAD (15). Aβ clearance also appears to be decreased with APOE4 (16), suggesting that soluble apoE/Aβ may modulate soluble Aβ and oAβ levels.

Research efforts to determine apoE/Aβ levels, particularly soluble complex levels, have been hindered by a lack of quantitative detection methods. A variety of techniques have produced results that can be inconsistent and difficult to interpret (7, 17–27). Even the initial biochemical characterizations of the molecular interactions between apoE and Aβ were problematic, primarily because of two parameters. The first variable was the lipidation state of apoE. Using purified protein, apoE4 bound Aβ with a higher affinity than apoE3 (28, 29). However, this result is reversed using physiologically relevant, lipidated apoE; levels of the apoE3/Aβ complex are significantly greater than the apoE4/Aβ complex (21, 28, 29). Second, the definition of an apoE/Aβ is primarily operational, with assay stringency the primary variable (7, 17–27, 30). For example, apoE3/Aβ levels are greater than apoE4/Aβ as determined by Western analysis of SDS-PAGE (21), but by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis, the levels of the apoE3/Aβ complex are comparable with apoE4/Aβ (31). Although these data are consistent with an SDS-stable apoE3/Aβ complex (32), and an apoE4/Aβ complex that is disrupted by SDS, the total amount of apoE/Aβ cannot be quantified by Western analysis of SDS-PAGE. The first goal of this study was to define biochemically generated apoE/Aβ in the context of a single quantitative and potentially high throughput method that would also define both total and detergent (SDS)-stable apoE/Aβ, providing a platform for comparison among apoE isoforms and across methods. Thus, a new apoE/Aβ ELISA was developed and optimized biochemically. In vitro, total complex levels were equivalent among the apoE isoforms, although the apoE3/Aβ complex was more SDS-stable than the apoE4/Aβ complex but was less SDS-stable than apoE2/Aβ. These results are consistent with previous results utilizing several methods that suggest the levels of apoE3/Aβ and apoE4/Aβ complex are comparable in the absence of SDS but that SDS-stable apoE3/Aβ complex levels are greater than apoE4/Aβ (18, 21, 22, 27).

In contrast to biochemical analysis, the number of in vivo reports on soluble apoE/Aβ is limited. ApoE/Aβ complex has been detected in the soluble fraction of human brain (33) and in human cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (30, 34), although the data were primarily produced using Western analysis of SDS-PAGE. By IHC, apoE also co-localizes with Aβ at the synapse (35), and insoluble apoE/Aβ complexes appear to form preferentially with apoE4 compared with apoE3 (36). However, the effect of the APOE genotype on soluble synaptic apoE/Aβ levels remains unclear (37–40). Thus, the new apoE/Aβ ELISA was used in vivo to determine the levels of soluble apoE/Aβ and the effect of the APOE genotype. In EFAD transgenic mice, previous data demonstrated that with APOE4 the soluble Aβ42 and oAβ levels were greater (15), and in the data presented herein, soluble apoE4/Aβ complex levels were lower and less stable compared with apoE3/Aβ and apoE2/Aβ levels. In human synaptosome preparations and CSF, apoE/Aβ levels were lower in AD compared with controls and with APOE4 compared with APOE3 in the AD cohort. Importantly, in human CSF, although total Aβ42 levels decreased in AD patients compared with controls, oAβ levels increased and were greater with APOE4 in the AD cohort. Taken together, the low levels of the soluble apoE4/Aβ complex and high levels of the soluble oAβ suggest an impaired clearance mechanism for the soluble forms of Aβ and a potential basis for APOE4-induced AD risk, as well as a mechanistic approach to CSF biomarkers for AD.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

High bind plates (MaxisorpTM) and low bind plates (MicrowellTM) were purchased from NUNC, Rochester, NY. Anti (α)-Aβ antibodies used were as follows: 6E10 (Covance Labs, Madison, WI); 4G8 (Senetek, Maryland Height, MD), and MOAB-2 (41) (LaDu Laboratory and available from Abcam, Cambridge, MA; Biosensis, Temecula, CA; Millipore, Bilerica, MA; Novus, Littleton, CO; and Cayman, Ann Arbor MI). Goat α-apoE antibodies were from Calbiochem, Meridian (Memphis, TN), and Millipore (Billerica, MA). Recombinant apoE3 was from BioVision (Milpitas, CA), and synthetic Aβ peptides were from California Peptide (Napa, CA).

HEK-ApoE

ApoE from HEK-293 cells stably transfected with human cDNA encoding apoE2, apoE3, or apoE4 was prepared as described previously (21, 42, 43). Briefly, serum-free conditioned media were concentrated ∼50-fold (Centriprep, Amicon, Inc.) and fractionated by size exclusion chromatography. The resulting fractions containing apoE particles were pooled and the concentration of apoE quantified.

Amyloid-β (Aβ) Peptide

Aβ peptides were prepared as described previously (44–46). 1,1,1,3,3,3-Hexafluoro-2-propanol-treated Aβ was dissolved in DMSO to 5 mm and then to 100 μm in phenol red-free F-12 media (BioSource, Camarillo, CA) for unaggregated and oAβ or 10 mm HCl for fibrillar Aβ. Unaggregated Aβ was freshly prepared just prior to use; oAβ42 preparations were aged for 24 h at 4 °C and fibrillar Aβ42 preparations for 24 h at 37 °C.

ApoE/Aβ Complex Standard Development and Biochemical Characterization

ApoE/Aβ Complex Formation

HEK-apoE or recombinant apoE and Aβ were incubated at the indicated concentrations for 2 h at room temperature, pH 7.4, with SDS (Sigma) or vehicle at the indicated concentrations. The pH profile for apoE/Aβ levels was conducted as described (21).

ELISA Curve Fitting

In the absence of SDS, the EC50 value for Aβ and apoE was calculated using the four-parameter logistic Equation 1,

|

Top and bottom represents the apoE/Aβ levels at the plateaus. EC50 is the concentration of Aβ or apoE that produces 50% maximal response. X is the concentration of the variable i.e. Aβ or apoE.

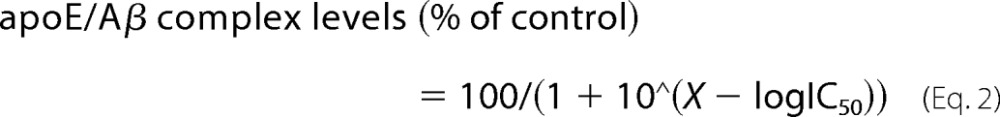

In the presence of SDS, the IC50 value for SDS was calculated according to Equation 2,

|

IC50 is the effective concentration of SDS that produces 50% response. X corresponds to the concentration of SDS.

Analysis was conducted for each individual experiment, and data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's post hoc analysis GraphPad Prism Version 5 for Macintosh was used for all curve-fitting analyses.

ApoE/Aβ Complex ELISA

Biochemical ELISA Development

To accurately quantify total and SDS-stable levels of apoE/Aβ, a specific ELISA was developed. The apoE/Aβ complex formed between HEK-apoE and unaggregated Aβ42 was utilized for ELISA development. To minimize nonspecific binding of apoE and Aβ and to maximize apoE/Aβ detection, a number of antibody combinations were screened as capture or detection antibodies on NUNC MaxisorpTM (high bind) or MicrowellTM (low bind) plates (supplemental Fig. 1). Results demonstrated the following. 1) Nonspecific binding of Aβ to high and low bind plates precludes the use of α-Aβ antibodies for detection. 2) Nonspecific binding of HEK-apoE prevents the use of high bind plates (supplemental Fig. 1A). 3) ApoE/Aβ complex, but not apoE or Aβ, is detected on low bind plates using α-apoE capture and α-Aβ detection antibodies (supplemental Fig. 1B). 4) α-Aβ (MOAB-2) capture and α-apoE (Calbiochem) detection antibodies produce the highest signal/background ratio compared with other antibodies tested (supplemental Fig. 1, C and D). Thus, the optimal reagents/conditions for specific HEK-apoE/Aβ detection by ELISA were low bind 96-well plates with α-Aβ (MOAB-2) capture and α-apoE (Calbiochem) detection antibodies.

ApoE/Aβ ELISA

For protocol 1, low bind plates were coated with MOAB-2 at 6.25 μg/ml in carbonate coating buffer overnight at 4 °C. Plates were washed (three times in PBS), blocked (4% BSA, 1.5 h, 37 °C), washed again (three times in PBS), and incubated with samples overnight. The plates were then washed (three times in PBS), incubated with a 200-fold dilution of α-apoE (Calbiochem) (1.5 h, 37 °C), washed, and incubated with HRP-conjugated antibodies (1.5 h, RT, 1:5000 dilution, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). Following a final wash step (three times in PBS), 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine liquid substrate Superslow (Sigma) was added, and absorbance was measured at A620. For protocol 2, all steps were identical to protocol 1, with the exception that high bind plates were utilized (see ELISA analysis of human CSF).

Soluble ApoE/Aβ Complex Detection in EFAD Mice

EFAD Transgenic Mice

Experiments follow the UIC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocols. EFAD mice (15) are the result of crossing 5×FAD mice, which co-express five FAD mutations (APP K670N/M671L, I716V, and V717I and PS1, M146L and L286V) under the control of the Thy-1 promoter with apoE-targeted replacement mice. Details on the production, breeding, genotyping, and genetic background of these mice are described in Ref. 15.

Tissue Preparation

Brain tissue isolation and serial protein extraction were conducted as described previously (5, 15). Briefly, 6-month-old male EFAD mice were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg) and transcardially perfused (PBS plus protease inhibitors (Calbiochem, set 3)), and brains were removed and dissected at the midline. Right hemi-brains were dissected on ice into cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum, immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until use. The dissected tissue was homogenized in 15 volumes (w/v) of TBS; samples were centrifuged (100,000 × g, 1 h at 4 °C), and the TBS (soluble) fraction was aliquoted prior to freezing in liquid nitrogen and storage at −80 °C.

ApoE/Aβ Complex

The apoE/Aβ levels were measured using a 4-fold sample dilution of the TBS extraction fraction from the hippocampus of EFAD mice according to apoE/Aβ ELISA protocol 1. The standard curve used a fixed HEK-apoE concentration of 140 nm (apoE concentration in the TBS extraction of EFAD mice at 6 months for all APOE genotypes) and varied Aβ concentrations. Data were normalized to protein concentration in each sample.

ApoE/Aβ Detection in Human Synaptosomes

Brain samples of parietal cortex (A7, A39, and A40) were obtained at autopsy for cases followed by the Alzheimer disease research centers at UCLA, University of California at Irvine, and University of Southern California (supplemental Table 1); the last clinical diagnosis and full neuropathological report and diagnosis were available for all cases. Control samples included normal cases and pathological controls. Immediately upon receipt, samples (∼0.3–5 g) were minced in 0.32 m sucrose with protease inhibitors (2 mm EDTA, 2 mm EGTA, 0.2 mm PMSF, 1 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 5 mm NaF, 10 mm Tris) and then stored at −70 °C until homogenization. The P-2 (crude synaptosome; synaptosome-enriched fraction) was prepared as described previously (42); briefly, tissue was homogenized in ice-cold buffer (0.32 m sucrose, 10 mm Tris, pH 7.5, plus protease inhibitors: pepstatin (4 mg/ml), aprotinin (5 mg/ml), trypsin inhibitor (20 mg/ml), EDTA (2 mm), EGTA (2 mm), PMSF (0.2 mm), leupeptin (4 mg/ml)). The homogenate was first centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min; the resulting supernatant was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 min to obtain the crude synaptosomal pellet. Aliquots of P-2 were routinely cryopreserved in 0.32 m sucrose and banked at −70 °C until the day of the experiment. On the day of the experiment, cryopreserved human P-2 aliquots were defrosted at 37 °C, resuspended in PBS with protease inhibitors, sonicated, and centrifuged for 4 min at 6000 rpm. Supernatant was collected, and total protein concentration was defined using BCA protein assay (Pierce). ApoE/Aβ complex levels were measured using a 5-fold sample dilution according to apoE/Aβ ELISA protocol 1. The standard curve used a fixed HEK-apoE concentration of 14 nm (apoE concentration in the synaptosomes) and varied Aβ concentrations. Human data were normalized according to total protein concentration in each sample.

ELISA Analysis of Human CSF

CSF samples were obtained at autopsy at the Alzheimer Disease Center at the University of Kentucky (supplemental Table 2). Diagnoses of AD and non-AD were performed at a consensus conference of the AD Center Neuropathology and Clinical Cores and were based upon evaluation of both cognitive status, i.e. Clinical Dementia rating and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores, as well as neuropathology, i.e. Braak stages that rate the extent of neurofibrillary pathology into the neocortex and the NIAReagan Institute neuropathology classification, which includes counts of both neuritic senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles and provides a likelihood staging of AD neuropathological diagnosis (47, 48). For ELISA analysis, Aβ42, total Tau (T-Tau), and phosphorylated Tau 181 (p-Tau-181) levels were measured using Innotest® ELISA kits (Innogenetics, Gent, Belgium) according to the manufacturer's protocol; apoE levels were measured using α-apoE (Millipore) as capture and α-apoE (Meridian) as detection as described (11). oAβ levels were measured using MOAB-2 capture (5) and biotinylated MOAB-2 as detection antibody as described previously (15). ApoE/Aβ complex levels were measured using a 2-fold sample dilution according to apoE/Aβ ELISA protocol 2, with a standard curve of 5 μg/ml recombinant apoE (reported CSF apoE concentration) and varied Aβ concentrations.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc analysis (Figs. 2, A and B, and 3–5) or by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc analysis (Fig. 2C). Correlation analysis was conducted using Spearman's correlation (Fig. 5, E and F). All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 5 for Macintosh, and p < 0.05 was considered significant. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves (Fig. 6) were constructed for each marker using the pROC package in R (49, 50). Areas under the curves were compared by the method of DeLong et al. (51).

FIGURE 2.

ApoE/Aβ complex levels and stability in soluble brain extracts from EFAD mice. A, standardization and control for apoE/Aβ levels in the soluble (TBS) extraction fraction from the hippocampus and cerebellum of E3FAD mice at 6 months. B, apoE/Aβ complex in the soluble extraction fraction from the hippocampus of E2FAD, E3FAD, and E4FAD mice at 6 months. C, soluble apoE/Aβ stability in 0.02% and 0.2% SDS in samples as described for B. Standard curve for apoE/Aβ ELISA, 140.0 nm HEK-apoE3 with 0.15–50.0 nm unaggregated Aβ42. For all experiments n = 8 with duplicate samples. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. and were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc analysis (B), or by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc analysis (C). *, p < 0.05.

FIGURE 3.

Soluble apoE/Aβ levels and stability in synaptosome-enriched extracts from human cortex. A and B were measured in age-matched control subjects (APOE3/3 and APOE4/X) and Alzheimer disease (AD) patients (APOE3/3 and APOE4/X). Description of sample groups is shown in supplemental Table 1. A, apoE/Aβ complex levels in cortical synaptosomes (P-2 fraction). Controls, n = 10 APOE3/3, n = 7 APOE4/X; AD, n = 9 APOE3/3, n = 7 APOE4/X. B, apoE/Aβ complex stability in 0.02% SDS. Standard curve for apoE/Aβ ELISA in human synaptosome-enriched extracts: 14.0 nm HEK-apoE3 with 0.86–450.0 nm unaggregated Aβ42. Controls, n = 5 APOE3/3, n = 5 APOE4/X; AD, n = 6 APOE3/3, n = 5 APOE4/X. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E., analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison post hoc analysis. *, p < 0.05.

FIGURE 4.

Oligomeric Aβ in human CSF compared with Aβ42, T-Tau, and p-Tau-181. A, standard curve for oligomeric Aβ ELISA: 0–500 ng/ml oligomeric, fibrillar, and unaggregated Aβ42 preparations. B–E were measured in the CSF from age-matched control subjects (APOE3/3) and AD patients (APOE3/3 and APOE4/4). Description of sample groups is shown in supplemental Table 2. B, oAβ. C, Aβ42. D, T-Tau; E, p-Tau-181. Innotest® kits by Innogenetics for Aβ42, T-Tau, and p-Tau-181. For all experiments n = 10 with duplicate samples. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E., analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison post hoc analysis. *, p < 0.05. L.O.D. = limit of detection.

FIGURE 5.

ApoE/Aβ complex levels in human CSF. A, standard curve for apoE/Aβ ELISA in human CSF, 5 μg/ml recombinant apoE3 with 0.15–50.0 ng/ml unaggregated Aβ42. B, specific apoE/Aβ detection by ELISA in control human APOE3/3 CSF. The standards and CSF samples were diluted 2–16-fold, and apoE/Aβ levels were measured. C, apoE/Aβ complex; D, apoE levels were measured in age-matched control subjects (APOE3/3) and AD patients (APOE3/3 and APOE4/4). Description of sample groups is shown in supplemental Table 2. For all experiments, n = 10 with duplicate samples. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E., analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison post hoc analysis. *, p < 0.05. L.O.D. = limit of detection. Spearman's correlation analysis between apoE/Aβ and apoE (E) or Aβ42 (F) in CSF of AD patients (APOE3/3 and APOE4/4).

FIGURE 6.

AD prediction by Aβ42, oAβ, apoE/Aβ, T-Tau, and p-Tau-181 in human CSF using ROC curves. ROC curves for Aβ42, oAβ, apoE/Aβ, T-Tau, and p-Tau-181 in control and AD patients with the APOE3/3 genotype in human CSF are shown. ROC curves represent the predicted probabilities of being an AD case using marginal logistic regression models. Specificity (true negative rate, the proportion of AD controls correctly predicted) is plotted on the x axis and sensitivity (the proportion of AD cases correctly predicted) is plotted on the y axis, as calculated based on each subject's predicted case probability being above or below the varying threshold, respectively.

RESULTS

Biochemical Development of ApoE/Aβ Complex ELISA

Initially, biochemical analysis using HEK-apoE and synthetic Aβ preparations (Fig. 1) (45) was conducted to validate the apoE/Aβ ELISA and to determine the effect of apoE isoform on soluble apoE/Aβ levels and stability.

FIGURE 1.

Biochemical characterization of apoE/Aβ ELISA with HEK-apoE and synthetic Aβ. A, total apoE/Aβ levels for each apoE isoform with HEK-apoE fixed at 30.0 nm and unaggregated Aβ42 varied from 0.15 to 150.0 nm. B, total level of apoE/Aβ for each apoE isoform with unaggregated Aβ42 fixed at 3.0 nm and HEK-apoE varied from 1.5 to 1500.0 nm. C, stability of apoE/Aβ in the presence of SDS from 0–2%. D, stability of apoE/Aβ at varied pH. For all experiments n = 5 with duplicate samples. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E., analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison post hoc analysis. *, p < 0.05 compared with apoE3;#, p < 0.05 compared with apoE2.

Total ApoE/Aβ Complex Levels Are Not Affected by ApoE Isoform

Total complex levels were measured in samples containing a fixed apoE concentration (30 nm) and a varied concentration of unaggregated Aβ42 (0.15–150 nm) (Fig. 1A) or using varied apoE concentration (0–1500 nm) and a fixed Aβ concentration (3 nm) (Fig. 1B). Overall, apoE/Aβ levels were saturable and dependent on apoE and Aβ concentrations but not apoE isoform. Indeed, when these data were analyzed using a four-parameter logistic equation, which is appropriate for analyzing ELISA saturation curves (52), there were no differences between the calculated EC50 values among the apoE isoforms (∼3 nm for Aβ in Fig. 3A and ∼30 nm for apoE in Fig. 1B). Total apoE/Aβ levels were also equivalent for apoE2, apoE3, and apoE4 with unaggregated Aβ40, oAβ42, and fibrillar Aβ42 (data not shown). Thus, apoE isoform does not determine total apoE/Aβ levels biochemically.

ApoE2/Aβ and ApoE3/Aβ Complex Exhibits Greater Stability than ApoE4/Aβ Complex

As apoE isoform did not affect total complex levels when assessed by ELISA, SDS was added to samples as a measure of stability (Fig. 1C). ApoE and Aβ were incubated for 2 h at concentrations that correspond to the EC50 values identified for total apoE/Aβ levels, specifically 3 nm Aβ42 and 30 nm apoE, and then SDS was added over a range of concentrations (up to 2%). Complex stability from highest to lowest was apoE2/Aβ > apoE3/Aβ > apoE4/Aβ. This was evident as the SDS IC50 value was 1.5-fold higher for apoE2/Aβ complex and 3-fold lower for the apoE4/Aβ complex compared with the apoE3/Aβ complex. In addition to SDS, the apoE4/Aβ complex was less stable at mildly acidic pH (5) than apoE2/Aβ and apoE3/Aβ complex (Fig. 1D). Therefore, apoE/Aβ levels were not determined by the apoE isoform; however, the apoE4/Aβ complex is less stable, and the apoE2/Aβ is more stable than the apoE3/Aβ complex.

Soluble ApoE/Aβ Complex Levels in EFAD Mice

To determine the effect of APOE genotype on soluble apoE/Aβ levels, the tractable EFAD mouse model was utilized. For this study, apoE/Aβ levels were measured in the soluble hippocampal homogenates from EFAD mice at 6 months (Fig. 2), an age where soluble oAβ levels are greater in E4FAD (APOE4) compared with E2FAD (APOE2) and E3FAD (APOE3) mice (15).

ApoE/Aβ Complex ELISA Optimization in EFAD Mice

Initially, soluble apoE/Aβ detection by ELISA was validated using E3FAD mice at 6 months (Fig. 2A). For a quantitative standard to enable cross-plate comparisons, the complex formed between HEK-apoE3 at a fixed concentration of 140 nm, which corresponds to soluble apoE levels in EFAD mice at 6 months, and a varied concentration of unaggregated Aβ42 was utilized. Specific soluble apoE/Aβ levels were detected by ELISA as follows. 1) Soluble hippocampal apoE/Aβ was only detected using MOAB-2 as a capture antibody, as no signal was seen when using a nonspecific IgG2b isotype-matched capture antibody. 2) Complex levels decreased with increased sample dilution. 3) There were no detectable soluble complex levels in the cerebellum, a region spared of Aβ pathology in EFAD mice. These data validate soluble apoE/Aβ detection in vivo by ELISA.

Soluble ApoE/Aβ Complex Levels Are Lower and Less Stable with APOE4

Next, the effect of APOE genotype on soluble apoE/Aβ levels and stability was determined. ApoE/Aβ complex levels were 50% lower in E4FAD mice compared with E2FAD and E3FAD mice (Fig. 2B). For apoE/Aβ stability (Fig. 2C), complex levels were measured from the same sample in the presence of 0, 0.02, or 0.2% SDS. Complex levels were normalized to the 0% SDS control for each paired samples set. The addition of SDS reduced apoE/Aβ levels, in an APOE genotype-specific manner. With 0.02% SDS, apoE4/Aβ complex levels were reduced by ∼60%, apoE3/Aβ complex levels by ∼50%, and apoE2/Aβ complex levels by ∼30%. The addition of 0.2% SDS further lowered complex levels in E3FAD and E4FAD mice but not E2FAD mice. These data demonstrate that soluble hippocampal apoE/Aβ levels are lower and less SDS-stable in E4FAD mice compared with E3FAD and E2FAD mice and that the apoE2/Aβ complex is more stable than the apoE3/Aβ complex.

Soluble ApoE/Aβ Complex in Synaptosomes

To determine the effect of AD and APOE genotype on soluble synaptic apoE/Aβ levels, cortical synaptosomes were isolated from control (APOE3/3 and APOE4/X) and AD patients (APOE3/3 and APOE4/X) (Fig. 3).

ApoE/Aβ Complex Levels Were Lower in AD Patients Compared with Controls and with APOE4 in the AD Cohort

In the absence of SDS (Fig. 3A), the data are normalized to APOE3/3 controls. In the control individuals, there was no significant difference between apoE/Aβ levels in the APOE3/3 and APOE4/X. In the AD patients, apoE/Aβ levels were significantly lower, i.e. 70% lower for APOE3/3 AD patients compared with APOE3/3 controls and 90% lower in APOE4/X AD patients compared with APOE4/X controls (Fig. 3A). In addition, within the AD cohort, total apoE/Aβ levels were 66% lower with APOE4/X compared with APOE3/3.

To address the SDS stability of the apoE/Aβ (Fig. 3B), complex levels were measured from the same sample in the presence of 0 or 0.02% SDS. ApoE/Aβ complex levels were then normalized to the 0% SDS control for each paired sample set. In the control individuals, the addition of SDS results in a significant decrease in apoE/Aβ levels with APOE4/X compared with APOE3/3. ApoE/Aβ complex stability was not significantly different in the APOE4/X AD patients compared with APOE3/3 AD patients. This is primarily due to the very low levels of complex present in APOE4/X AD samples in the absence of SDS (Fig. 3A); thus, after the addition of SDS, any further reduction results in values for the complex that are at the limit of detection for this ELISA. Again, this results from the pairwise comparison between apoE/Aβ levels in APOE4/X AD patients in the absence of SDS (for example Fig. 3A), where the levels of apoE/Aβ are already low, and apoE/Aβ levels in the presence of SDS (Fig. 3B).

ApoE/Aβ Complex in Human CSF

The CSF is as an indication of the concentration of soluble proteins in the brain parenchyma. Therefore, the hypothesis that reduced levels of soluble apoE/Aβ and an increase in soluble oAβ levels are associated with AD and APOE4 was tested in post-mortem CSF samples from control (APOE3/3) and AD patients (APOE3/3 and APOE4/4).

Oligomeric Aβ Levels Were Higher in AD Patients Compared with Controls and Significantly Greater with APOE4 within the AD Cohort

Recently, we described an oAβ ELISA that detects oAβ levels in EFAD mice (15), using a previously described oAβ preparation (53). For this study, a protocol characterized by our laboratory (46) was used to produce the oAβ standard and is shown compared with fibrillar and unaggregated Aβ42 preparations (Fig. 4A). As demonstrated in Fig. 4A, the oAβ ELISA demonstrates concentration-dependent detection of oAβ, with a significantly lower affinity for fibrillar Aβ42 and no detection of unaggregated Aβ42.

This ELISA was used to determine whether oAβ levels were influenced by AD diagnosis or APOE genotype. oAβ levels were significantly increased in AD patients compared with controls, and importantly, oAβ levels were significantly greater in APOE4/4 AD patients compared with APOE3/3 AD patients (Fig. 4B). For comparative purposes, the established AD biomarkers Aβ42 (Fig. 4C), total Tau (T-Tau) (Fig. 4D), and phosphorylated Tau 181 (p-Tau-181) (Fig. 4E) levels were measured by ELISAs (54) in the same samples as oAβ. As expected, Aβ42 levels were significantly lower, and p-Tau-181 levels significantly greater in both the AD groups (APOE3/3 and APOE4/4) compared with age-matched controls (APOE3/3). T-Tau levels were significantly greater in the APOE4/4 AD patients but not the APOE3/3 AD patients compared with the APOE3/3 controls. Of particular interest, in the AD group, APOE genotype did not affect the levels of Aβ42, T-Tau, or p-Tau-181, all established AD biomarkers. Thus, oAβ levels may play a role in AD progression, in an APOE genotype-specific manner.

ApoE/Aβ Complex ELISA Optimization for Human CSF

An important consideration for measuring specific proteins in the CSF by ELISA is a standard to allow quantification of samples used on different microplates, across studies, so as to allow future retrospective analysis. Although HEK-apoE is an important apoE source for biochemical studies, the relatively long sample preparation time, potential intra-laboratory differences in production quality, long term stability issues, and lack of commercialization hinders routine use as an apoE/Aβ standard. Therefore, apoE/Aβ formed between recombinant apoE3, at concentrations corresponding to those in human CSF (5 μg/ml), and varied unaggregated Aβ42 concentrations was used as a standard curve for the CSF samples (Fig. 5A). Specific apoE/Aβ detection by ELISA in human CSF (APOE3/3 control) was demonstrated by a high signal with capture antibody (MOAB-2) that decreased proportionately to sample dilution and no observed signal without a capture antibody, all using high bind plates to increase sensitivity (Fig. 5B).

ApoE/Aβ Complex Levels Were Lower in CSF from AD Patients Compared With Controls and, Importantly, Significantly Lower with APOE4 within the AD Cohort

ApoE/Aβ complex levels may modulate soluble oAβ levels in the CNS. The increased oAβ levels by AD and APOE4 raised the important question of what was the effect on apoE/Aβ levels. ApoE/Aβ complex levels were significantly lower in both AD cohorts compared with the control group (Fig. 5C). Importantly, complex levels were significantly lower in APOE4/4 AD patients compared with the APOE3/3 AD patients. Thus, APOE4 did affect the levels of oAβ (increased) and apoE/Aβ (decreased) in the AD cohort and did not affect the levels of Aβ42, T-Tau, or p-Tau-181, suggesting oAβ and apoE/Aβ levels may play a role in AD progression. Although apoE levels were lower in AD patients compared with controls (Fig. 5D), there was no correlation between apoE/Aβ levels and either apoE (Fig. 5E, Spearman's r value 0.27, p = 0.25) or Aβ42 (Fig. 5F, Spearman's r value 0.04, p = 0.87) levels in the AD patient sample set. This suggests that the levels of apoE/Aβ are independent of the values of its two components. Thus, apoE/Aβ levels are affected by both AD and APOE genotype.

oAβ and ApoE/Aβ Complex as AD Biomarkers

In addition to a potential mechanistic interpretation for AD progression, oAβ and apoE/Aβ levels may act as AD biomarkers. As APOE genotype affects oAβ and apoE/Aβ levels, the optimal method for assessing the diagnostic potential of these markers is analysis in control and AD patients with the APOE3/3 genotype. ROC curves were utilized to determine the predictive accuracy of each marker (Fig. 6). The ROC curves are constructed by varying the threshold to classify predicted AD cases and controls. Predicted probabilities of being an AD case are calculated from marginal logistic regression models, and sensitivity (the proportion of AD cases correctly predicted, y axis) and specificity (the proportion of AD controls correctly predicted, i.e. true negative rate, x axis) are calculated based on each subject's predicted case probability being above or below the varying threshold, respectively. The area under the curve (AUC) of the ROC curves is calculated, and an AUC of 0.5 demonstrates no information or diagnostic ability, whereas the higher the AUC is above 0.5, the greater the diagnostic accuracy of the biomarker. ROC analysis demonstrated the potential use of both oAβ and apoE/Aβ as AD biomarkers, with AUCs of 0.7 and 0.875, respectively. Next, the ROC AUCs of oAβ and apoE/Aβ were compared with the traditional AD biomarkers as follows: Aβ42, p-Tau-181, and T-Tau. Aβ42 was significantly more predictive of AD (p < 0.05) compared with the other markers except apoE/Aβ (p = 0.14). Both oAβ (p = 0.70) and apoE/Aβ (p = 0.41) complexes were as predictive for AD as p-Tau-181, and apoE/Aβ was more predictive than T-Tau (p < 0.012). Overall, in control and AD patients with the APOE3/3 genotype, the estimated predictive ability for AD based on the AUC values for each marker was Aβ42 (AUC = 0.98) ≥ apoE/Aβ (0.875) > p-Tau-181 (0.775) ≥ oAβ (0.7) > T-Tau (0.59).

DISCUSSION

For this study, a quantitative apoE/Aβ ELISA was developed and characterized biochemically and then applied in vivo to determine the effect of the APOE genotype and AD on soluble levels of apoE/Aβ complex and oAβ. Soluble levels of oAβ are higher, and apoE/Aβ are lower with AD and specifically APOE4.

Biochemical data using HEK-apoE demonstrate that the apoE isoform does not affect total levels of apoE/Aβ but that the apoE4/Aβ complex is less stable than the apoE3/Aβ complex. By measuring total and SDS-stable apoE/Aβ levels, these results resolve previous contradictory in vitro findings (21, 28, 30, 43). HEK-apoE has been utilized in numerous studies for apoE/Aβ formation (21, 28). Previous data have demonstrated that HEK-apoE3 but not HEK-apoE4 forms an SDS-stable apoE/Aβ as measured using Western analysis of SDS-PAGE (21, 28, 30, 43). However, a corresponding value for total complex levels was not possible by Western analysis. With this new ELISA, the apoE isoforms exhibit a comparable affinity for Aβ in the absence of SDS, defined here as total apoE/Aβ, consistent with previous reports using nonstringent conditions to measure the complex (31). The mechanism by which the apoE4/Aβ complex is less stable is unclear. ApoE4/Aβ disruption can occur by global effects on protein structure, disrupting the binding sites on the individual proteins, as well as local effects at the complex interface. ApoE4 has a lower stability and increased propensity to populate an intermediate molten globule conformation compared with the other isoforms (55, 56). The apoE4/Aβ complex exhibits the lowest stability under all denaturing conditions, potentially due to the greater susceptibility of the apoE4 tertiary structure to disruption. Therefore, specific effects on the complex interface cannot be separated from effects on the stability/structure of the individual components apoE and Aβ. An additional consideration for the stability of the apoE/Aβ is the effect of apoE isoform on lipoprotein lipidation. Increased lipoprotein lipidation increases the levels of SDS-stable apoE/Aβ, as determined by Western analysis of SDS-PAGE (21, 22, 30, 43, 57, 58). If glial cell-derived apoE4 is less lipidated than apoE3, the apoE4/Aβ complex would be less stable (59, 60). Thus, the biochemical development and characterization of the ELISA have resolved some of the inconsistencies in the apoE/Aβ literature. Having validated the ELISA in vitro, we used it in vivo to address the hypothesis that the levels of soluble apoE/Aβ isoform specially modulate oAβ levels.

Soluble oAβ levels are thought to include the proximal neurotoxic Aβ assemblies in AD (61). Soluble oAβ assemblies are neurotoxic in vitro and in vivo (61), and both soluble Aβ and oAβ correlate with disease progression in AD patients (62–65). We previously demonstrated that soluble levels of total Aβ42 and oAβ were increased in E4FAD transgenic mice compared with E2FAD and E3FAD, although the levels of apoE were comparable, suggesting a functional difference between the isoforms. In this study, soluble apoE4/Aβ complex levels were lower than apoE2/Aβ and apoE3/Aβ complex levels in EFAD mice. These data indicate an inverse association between apoE/Aβ and oAβ levels and are consistent with previous publications that suggest that apoE/Aβ levels isoform-specifically modulate soluble Aβ (11, 15). Synapse degeneration is considered a proximal cause of cognitive deficits in AD. ApoE/Aβ complex levels may affect synaptic Aβ levels and function. At the synapse, as with the whole brain, apoE/Aβ appears to be present as an insoluble and soluble form. IHC co-localization of apoE and Aβ at the synapse is a measure of primarily insoluble apoE/Aβ (35, 36), and data demonstrate insoluble apoE/Aβ appears to form preferentially with apoE4 compared with apoE3 (36). Previous results have shown that the detergent and guanidine extraction pattern of mouse apoE parallels that of Aβ42 in 5×FAD mice (5), and the proportion of apoE/Aβ in insoluble fractions was increased in AD synaptosomes compared with controls.6 Importantly, insoluble apoE4/Aβ complex may accumulate in autophagic structures within synaptic terminals (66, 67). However, the effect of APOE genotype on soluble synaptic apoE/Aβ levels is less clear. Soluble Aβ, soluble oAβ, p-Tau, and SDS-stable p-Tau oligomers (37–39, 68) are detected in AD synaptosomes, and data presented herein also demonstrate the presence of soluble apoE/Aβ in AD synaptosomes, with levels reduced compared with controls. Soluble apoE/Aβ levels were also lower in synaptosomes from AD patients with APOE4 compared with APOE3. These data indicate a difference in apoE/Aβ solubility during disease progression, which may lead to alterations in synaptic Aβ trafficking or clearance.

Although the cellular process by which the apoE isoform modulates soluble Aβ pathology is unclear, a number of apoE/Aβ-based mechanisms have been proposed. Examples include effects on the following: 1) Aβ oligomerization (69, 70); 2) Aβ clearance via glia (71–74), neurons (75, 76), and/or the blood-brain barrier (77, 78); 3) enzymatic degradation (57); and 4) drainage via the interstitial fluid (ISF) (16) or perivasculature (79). Furthermore, the dynamic compartmentalization of Aβ in the CNS has been identified as an important factor in regulating the level of soluble Aβ (80), which may be affected by and/or affect apoE/Aβ. Importantly, the levels of Aβ in each compartment affect the equilibrium between compartments, again with further modulation by the apoE isoforms. To understand this process, new techniques have been developed to determine apoE and Aβ turnover via stable isotope-labeling kinetics (81) and microdialysis of ISF (80). In addition, Hong et al. (80) have recently identified Aβ in biochemically distinct compartments in the brain, including an ISF pool, a TBS-extractable pool, an SDS-extractable pool, and an insoluble or plaque pool. In FAD-Tg mice with a high plaque burden, ISF Aβ appears to be rapidly sequestered in a TBS-soluble pool (80). Overall, the majority of Aβ in the ISF originates from a less soluble parenchymal Aβ pool rather than from production (80). ApoE isoform-specific apoE/Aβ levels could affect the dynamic compartmentalization of Aβ through the mechanisms discussed above. For example, with APOE3, high levels of soluble apoE/Aβ may reduce soluble and oAβ levels via clearance. With APOE4, low levels of soluble apoE/Aβ may result in increased soluble Aβ levels, particularly oAβ. Alternatively, if apoE is acting as a pathological chaperone for soluble Aβ, reducing the level or stability of apoE/Aβ may decrease oAβ levels (24, 82). As described herein, the ability to detect apoE isoform-specific differences in the levels of soluble oAβ and apoE/Aβ levels in vivo is a critical step in identifying the mechanism by which the apoE isoforms modulate soluble Aβ pathology.

As with human synaptosomes, in human CSF levels of soluble oAβ were greater and apoE/Aβ lower with APOE4 compared with APOE3 in the AD cohort. The ability of both oAβ and apoE/Aβ to distinguish between APOE3/3 and APOE4/4 AD patients is consistent with the increased risk and earlier age of disease onset with APOE4, highlighting the potential for these markers to track disease progression. In addition, apoE/Aβ and oAβ may represent novel CSF biomarkers, an important focus for AD research (54). In control and AD patients with the APOE3/3 genotype, both oAβ and apoE/Aβ diagnosed AD with the same accuracy as p-Tau-181, a currently accepted AD biomarker. Furthermore, as oAβ and apoE/Aβ are based on potential mechanisms of AD progression, both represent biomarkers to assess therapeutic efficacy in vivo and in clinical trials. Currently, drug trials targeting oAβ and apoE/Aβ are either in the preclinical phase or underway. For Aβ, therapies include both passive and active Aβ immunotherapy, β-secretase inhibitors, γ-secretase inhibitors, and γ-secretase modulators. Aside from measures of cognition, neuroimaging for amyloid with Pittsburgh compound B and CSF biomarkers such as Aβ42 and p-Tau levels are the only biomarkers available to determine drug efficacy (83). Given that amyloid plaques appear not to correlate with dementia and may not represent the ideal target, and it is unclear whether low CSF Aβ42 levels will be reversible with long term treatment, the relevance of these biomarkers for therapeutic trials is unclear. oAβ levels represent a novel biomarker to monitor drug efficacy. For apoE/Aβ, therapies are in development that disrupt (24, 82) or increase (84) apoE/Aβ levels. Examples include retinoid X receptor, liver X receptor, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ agonists, which increase the levels and lipidation state of apoE (57, 84–86), apoE structural correctors (87), and Aβ12–28P that blocks apoE/Aβ interactions (24, 82). However, there are no data on whether these drugs will affect apoE/Aβ levels in vivo, and more importantly, the effects of these therapeutic interventions on the human apoE isoforms are unknown. The data presented here indicate that increasing soluble levels of apoE/Aβ is a therapeutic target, as it will reduce oAβ levels. Importantly the efficacy of therapeutic treatments targeting soluble levels of oAβ and apoE/Aβ can now be determined using the ELISAs described herein.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Human post-mortem samples were obtained from the Alzheimer's Disease Research Center Neuropathology Cores of the University of Southern California (supported by National Institutes of Health Grant 050 AG05142 from NIA), UCLA (supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P50 AG 16970 from NIA), and University of California at Irvine (supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P50 AG016573 from NIA). Human CSF samples were obtained from the University of Kentucky Alzheimer's Disease Research Center (supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P30 AG028383 from NIA). We also gratefully acknowledge Maria Corrada and Claudia Kawas and the 90+ Study for providing tissue (University of California at Irvine).

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants P01AG030128 from NIA (to M. J. L. and S. E.), AG27465 (to K. H. G.), and G18879 (to C. A. M.). This work was also supported by Alzheimer's Association Grant ZEN-08-899000 (to M. J. L.), University of Illinois at Chicago Center for Clinical and Translational Science Grant UL1RR029879 (to M. J. L.), and an Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation Grant (to M. J. L. and S. E.).

This article was selected as a Paper of the Week.

This article contains supplemental Fig. S1 and Tables 1 and 2.

K. H. Gylys, unpublished observations.

- AD

- Alzheimer disease

- Aβ

- amyloid-β

- apoE

- apolipoprotein E

- AUC

- area under the curve

- CSF

- cerebrospinal fluid

- FAD

- familial AD

- FAD-Tg

- transgenic mice expressing FAD mutations

- IHC

- immunohistochemistry

- 5×FAD mice

- FAD-Tg that co-express five FAD mutations

- oAβ

- oligomeric amyloid-β

- ROC

- receiver operating characteristic curves

- Tg

- transgenic

- T-Tau

- total Tau

- p-Tau-181

- phosphorylated Tau at residue 181

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- ISF

- interstitial fluid.

REFERENCES

- 1. Verghese P. B., Castellano J. M., Holtzman D. M. (2011) Apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer's disease and other neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 10, 241–252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bu G. (2009) Apolipoprotein E and its receptors in Alzheimer's disease. Pathways, pathogenesis, and therapy. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 333–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hardy J. A., Higgins G. A. (1992) Alzheimer's disease. The amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science 256, 184–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wisniewski T., Frangione B. (1992) Apolipoprotein E. A pathological chaperone protein in patients with cerebral and systemic amyloid. Neurosci. Lett. 135, 235–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Youmans K. L., Leung S., Zhang J., Maus E., Baysac K., Bu G., Vassar R., Yu C., LaDu M. J. (2011) Amyloid-β42 alters apolipoprotein E solubility in brains of mice with five familial AD mutations. J. Neurosci. Methods 196, 51–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Strittmatter W. J., Saunders A. M., Goedert M., Weisgraber K. H., Dong L. M., Jakes R., Huang D. Y., Pericak-Vance M., Schmechel D., Roses A. D. (1994) Isoform-specific interactions of apolipoprotein E with microtubule-associated protein Tau. Implications for Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 11183–11186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Strittmatter W. J., Saunders A. M., Schmechel D., Pericak-Vance M., Enghild J., Salvesen G. S., Roses A. D. (1993) Apolipoprotein E. High avidity binding to β-amyloid and increased frequency of type 4 allele in late-onset familial Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 1977–1981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Drzezga A., Grimmer T., Henriksen G., Mühlau M., Perneczky R., Miederer I., Praus C., Sorg C., Wohlschläger A., Riemenschneider M., Wester H. J., Foerstl H., Schwaiger M., Kurz A. (2009) Effect of APOE genotype on amyloid plaque load and gray matter volume in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 72, 1487–1494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grimmer T., Tholen S., Yousefi B. H., Alexopoulos P., Förschler A., Förstl H., Henriksen G., Klunk W. E., Mathis C. A., Perneczky R., Sorg C., Kurz A., Drzezga A. (2010) Progression of cerebral amyloid load is associated with the apolipoprotein E ϵ4 genotype in Alzheimer's disease. Biol. Psychiatry 68, 879–884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jones P. B., Adams K. W., Rozkalne A., Spires-Jones T. L., Hshieh T. T., Hashimoto T., von Armin C. A., Mielke M., Bacskai B. J., Hyman B. T. (2011) Apolipoprotein E. Isoform-specific differences in tertiary structure and interaction with amyloid-β in human Alzheimer brain. PloS ONE 6, e14586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bales K. R., Liu F., Wu S., Lin S., Koger D., DeLong C., Hansen J. C., Sullivan P. M., Paul S. M. (2009) Human APOE isoform-dependent effects on brain β-amyloid levels in PDAPP transgenic mice. J. Neurosci. 29, 6771–6779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Haass C., Selkoe D. J. (2007) Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration. Lessons from the Alzheimer's amyloid β-peptide. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 101–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hardy J. (2006) Alzheimer's disease. The amyloid cascade hypothesis. An update and reappraisal. J. Alzheimers Dis. 9, 151–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Larson M. E., Lesne S. E. (2012) Soluble Aβ oligomer production and toxicity. J. Neurochem. 120, Suppl. 1, 125–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Youmans K. L., Tai L. M., Nwabuisi-Heath E., Jungbauer L., Kanekiyo T., Gan M., Kim J., Eimer W. A., Estus S., Rebeck G. W., Weeber E. J., Bu G., Yu C., Ladu M. J. (2012) APOE4-specific changes in Aβ accumulation in a new transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 41774–41786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Castellano J. M., Kim J., Stewart F. R., Jiang H., DeMattos R. B., Patterson B. W., Fagan A. M., Morris J. C., Mawuenyega K. G., Cruchaga C., Goate A. M., Bales K. R., Paul S. M., Bateman R. J., Holtzman D. M. (2011) Human apoE isoforms differentially regulate brain amyloid-β peptide clearance. Sci. Transl. Med. 3, 89ra57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aleshkov S., Abraham C. R., Zannis V. I. (1997) Interaction of nascent ApoE2, ApoE3, and ApoE4 isoforms expressed in mammalian cells with amyloid peptide β(1–40). Relevance to Alzheimer's disease. Biochemistry 36, 10571–10580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bentley N. M., Ladu M. J., Rajan C., Getz G. S., Reardon C. A. (2002) Apolipoprotein E structural requirements for the formation of SDS-stable complexes with β-amyloid-(1–40). The role of salt bridges. Biochem. J. 366, 273–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Golabek A., Marques M. A., Lalowski M., Wisniewski T. (1995) Amyloid β-binding proteins in vitro and in normal human cerebrospinal fluid. Neurosci. Lett. 191, 79–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Golabek A. A., Soto C., Vogel T., Wisniewski T. (1996) The interaction between apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer's amyloid β-peptide is dependent on β-peptide conformation. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 10602–10606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. LaDu M. J., Falduto M. T., Manelli A. M., Reardon C. A., Getz G. S., Frail D. E. (1994) Isoform-specific binding of apolipoprotein E to β-amyloid. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 23403–23406 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. LaDu M. J., Lukens J. R., Reardon C. A., Getz G. S. (1997) Association of human, rat, and rabbit apolipoprotein E with β-amyloid. J. Neurosci. Res. 49, 9–18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pillot T., Goethals M., Vanloo B., Lins L., Brasseur R., Vandekerckhove J., Rosseneu M. (1997) Specific modulation of the fusogenic properties of the Alzheimer β-amyloid peptide by apolipoprotein E isoforms. Eur. J. Biochem. 243, 650–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sadowski M., Pankiewicz J., Scholtzova H., Ripellino J. A., Li Y., Schmidt S. D., Mathews P. M., Fryer J. D., Holtzman D. M., Sigurdsson E. M., Wisniewski T. (2004) A synthetic peptide blocking the apolipoprotein E/β-amyloid binding mitigates β-amyloid toxicity and fibril formation in vitro and reduces β-amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Am. J. Pathol. 165, 937–948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yamauchi K., Tozuka M., Hidaka H., Nakabayashi T., Sugano M., Kondo Y., Nakagawara A., Katsuyama T. (2000) Effect of apolipoprotein AII on the interaction of apolipoprotein E with β-amyloid. Some apo(E-AII) complexes inhibit the internalization of β-amyloid in cultures of neuroblastoma cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 62, 608–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yang D. S., Smith J. D., Zhou Z., Gandy S. E., Martins R. N. (1997) Characterization of the binding of amyloid-β peptide to cell culture-derived native apolipoprotein E2, E3, and E4 isoforms and to isoforms from human plasma. J. Neurochem. 68, 721–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhou Z., Smith J. D., Greengard P., Gandy S. (1996) Alzheimer amyloid-β peptide forms denaturant-resistant complex with type ϵ3 but not type ϵ4 isoform of native apolipoprotein E. Mol. Med. 2, 175–180 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. LaDu M. J., Pederson T. M., Frail D. E., Reardon C. A., Getz G. S., Falduto M. T. (1995) Purification of apolipoprotein E attenuates isoform-specific binding to β-amyloid. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 9039–9042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Strittmatter W. J., Weisgraber K. H., Huang D. Y., Dong L. M., Salvesen G. S., Pericak-Vance M., Schmechel D., Saunders A. M., Goldgaber D., Roses A. D. (1993) Binding of human apolipoprotein E to synthetic amyloid β-peptide. Isoform-specific effects and implications for late-onset Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 8098–8102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. LaDu M. J., Munson G. W., Jungbauer L., Getz G. S., Reardon C. A., Tai L. M., Yu C. (2012) Preferential interactions between ApoE-containing lipoproteins and Aβ revealed by a detection method that combines size exclusion chromatography with nonreducing gel-shift. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1821, 295–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Morikawa M., Fryer J. D., Sullivan P. M., Christopher E. A., Wahrle S. E., DeMattos R. B., O'Dell M. A., Fagan A. M., Lashuel H. A., Walz T., Asai K., Holtzman D. M. (2005) Production and characterization of astrocyte-derived human apolipoprotein E isoforms from immortalized astrocytes and their interactions with amyloid-β. Neurobiol. Dis. 19, 66–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Manelli A. M., Stine W. B., Van Eldik L. J., LaDu M. J. (2004) ApoE and Aβ1–42 interactions. Effects of isoform and conformation on structure and function. J. Mol. Neurosci. 23, 235–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Russo C., Angelini G., Dapino D., Piccini A., Piombo G., Schettini G., Chen S., Teller J. K., Zaccheo D., Gambetti P., Tabaton M. (1998) Opposite roles of apolipoprotein E in normal brains and in Alzheimer's disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 15598–15602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhou Z., Relkin N., Ghiso J., Smith J. D., Gandy S. (2002) Human cerebrospinal fluid apolipoprotein E isoforms are apparently inefficient at complexing with synthetic Alzheimer's amyloid-β peptide (Aβ1–40) in vitro. Mol. Med. 8, 376–381 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Arold S., Sullivan P., Bilousova T., Teng E., Miller C. A., Poon W. W., Vinters H. V., Cornwell L. B., Saing T., Cole G. M., Gylys K. H. (2012) Apolipoprotein E level and cholesterol are associated with reduced synaptic amyloid β in Alzheimer's disease and apoE TR mouse cortex. Acta Neuropathol. 123, 39–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Koffie R. M., Hashimoto T., Tai H. C., Kay K. R., Serrano-Pozo A., Joyner D., Hou S., Kopeikina K. J., Frosch M. P., Lee V. M., Holtzman D. M., Hyman B. T., Spires-Jones T. L. (2012) Apolipoprotein E4 effects in Alzheimer's disease are mediated by synaptotoxic oligomeric amyloid-β. Brain 135, 2155–2168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Henkins K. M., Sokolow S., Miller C. A., Vinters H. V., Poon W. W., Cornwell L. B., Saing T., Gylys K. H. (2012) Extensive p-Tau pathology and SDS-stable p-Tau oligomers in Alzheimer's cortical synapses. Brain Pathol. 22, 826–833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gylys K. H., Fein J. A., Yang F., Wiley D. J., Miller C. A., Cole G. M. (2004) Synaptic changes in Alzheimer's disease. Increased amyloid-β and gliosis in surviving terminals is accompanied by decreased PSD-95 fluorescence. Am. J. Pathol. 165, 1809–1817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fein J. A., Sokolow S., Miller C. A., Vinters H. V., Yang F., Cole G. M., Gylys K. H. (2008) Co-localization of amyloid β and Tau pathology in Alzheimer's disease synaptosomes. Am. J. Pathol. 172, 1683–1692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gylys K. H., Fein J. A., Yang F., Miller C. A., Cole G. M. (2007) Increased cholesterol in Aβ-positive nerve terminals from Alzheimer's disease cortex. Neurobiol. Aging 28, 8–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Youmans K. L., Tai L. M., Kanekiyo T., Stine W. B., Jr., Michon S. C., Nwabuisi-Heath E., Manelli A. M., Fu Y., Riordan S., Eimer W. A., Binder L., Bu G., Yu C., Hartley D. M., LaDu M. J. (2012) Intraneuronal Aβ detection in 5×FAD mice by a new Aβ-specific antibody. Mol. Neurodegeneration 7, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Munson G. W., Roher A. E., Kuo Y. M., Gilligan S. M., Reardon C. A., Getz G. S., LaDu M. J. (2000) SDS-stable complex formation between native apolipoprotein E3 and β-amyloid peptides. Biochemistry 39, 16119–16124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. LaDu M. J., Stine W. B., Jr., Narita M., Getz G. S., Reardon C. A., Bu G. (2006) Self-assembly of HEK cell-secreted ApoE particles resembles ApoE enrichment of lipoproteins as a ligand for the LDL receptor-related protein. Biochemistry 45, 381–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dahlgren K. N., Manelli A. M., Stine W. B., Jr., Baker L. K., Krafft G. A., LaDu M. J. (2002) Oligomeric and fibrillar species of amyloid-β peptides differentially affect neuronal viability. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 32046–32053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stine W. B., Jr., Dahlgren K. N., Krafft G. A., LaDu M. J. (2003) In vitro characterization of conditions for amyloid-β peptide oligomerization and fibrillogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 11612–11622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stine W. B., Jungbauer L., Yu C., LaDu M. J. (2011) Preparing synthetic Aβ in different aggregation states. Methods Mol. Biol. 670, 13–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. The National Institute on Aging, and Reagan Institute Working Group on Diagnostic Criteria for the Neuropathological Assessment of Alzheimer's Disease (1997) Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging 18, S1–S2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nelson P. T., Braak H., Markesbery W. R. (2009) Neuropathology and cognitive impairment in Alzheimer disease. A complex but coherent relationship. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 68, 1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Robin X., Turck N., Hainard A., Tiberti N., Lisacek F., Sanchez J. C., Müller M. (2011) pROC. An open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. R Development Core Team (2012) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria: ISBN 3–900051-07-0 [Google Scholar]

- 51. DeLong E. R., DeLong D. M., Clarke-Pearson D. L. (1988) Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves. A nonparametric approach. Biometrics 44, 837–845 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Findlay J. W., Dillard R. F. (2007) Appropriate calibration curve fitting in ligand binding assays. AAPS J. 9, E260–E267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Moore B. D., Rangachari V., Tay W. M., Milkovic N. M., Rosenberry T. L. (2009) Biophysical analyses of synthetic amyloid-β(1–42) aggregates before and after covalent cross-linking. Implications for deducing the structure of endogenous amyloid-β oligomers. Biochemistry 48, 11796–11806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Shoji M. (2011) Biomarkers of the dementia. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2011:564321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Morrow J. A., Hatters D. M., Lu B., Hochtl P., Oberg K. A., Rupp B., Weisgraber K. H. (2002) Apolipoprotein E4 forms a molten globule. A potential basis for its association with disease. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 50380–50385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Morrow J. A., Segall M. L., Lund-Katz S., Phillips M. C., Knapp M., Rupp B., Weisgraber K. H. (2000) Differences in stability among the human apolipoprotein E isoforms determined by the amino-terminal domain. Biochemistry 39, 11657–11666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Jiang Q., Lee C. Y., Mandrekar S., Wilkinson B., Cramer P., Zelcer N., Mann K., Lamb B., Willson T. M., Collins J. L., Richardson J. C., Smith J. D., Comery T. A., Riddell D., Holtzman D. M., Tontonoz P., Landreth G. E. (2008) ApoE promotes the proteolytic degradation of Aβ. Neuron 58, 681–693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hirsch-Reinshagen V., Maia L. F., Burgess B. L., Blain J. F., Naus K. E., McIsaac S. A., Parkinson P. F., Chan J. Y., Tansley G. H., Hayden M. R., Poirier J., Van Nostrand W., Wellington C. L. (2005) The absence of ABCA1 decreases soluble ApoE levels but does not diminish amyloid deposition in two murine models of Alzheimer disease. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 43243–43256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gong J. S., Kobayashi M., Hayashi H., Zou K., Sawamura N., Fujita S. C., Yanagisawa K., Michikawa M. (2002) Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) isoform-dependent lipid release from astrocytes prepared from human ApoE3 and ApoE4 knock-in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 29919–29926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Riddell D. R., Zhou H., Atchison K., Warwick H. K., Atkinson P. J., Jefferson J., Xu L., Aschmies S., Kirksey Y., Hu Y., Wagner E., Parratt A., Xu J., Li Z., Zaleska M. M., Jacobsen J. S., Pangalos M. N., Reinhart P. H., (2008) Impact of apolipoprotein E (ApoE) polymorphism on brain ApoE levels. J. Neurosci. 28, 11445–11453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Walsh D. M., Teplow D. B. (2012) Alzheimer's disease and the amyloid β-protein. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 107, 101–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kuo Y. M., Emmerling M. R., Vigo-Pelfrey C., Kasunic T. C., Kirkpatrick J. B., Murdoch G. H., Ball M. J., Roher A. E. (1996) Water-soluble Aβ (N-40, N-42) oligomers in normal and Alzheimer disease brains. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 4077–4081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Selkoe D. J. (2011) Resolving controversies on the path to Alzheimer's therapeutics. Nat. Med. 17, 1060–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Tomic J. L., Pensalfini A., Head E., Glabe C. G. (2009) Soluble fibrillar oligomer levels are elevated in Alzheimer's disease brain and correlate with cognitive dysfunction. Neurobiol. Dis. 35, 352–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Jin M., Shepardson N., Yang T., Chen G., Walsh D., Selkoe D. J. (2011) Soluble amyloid β-protein dimers isolated from Alzheimer cortex directly induce Tau hyperphosphorylation and neuritic degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 5819–5824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Nixon R. A. (2007) Autophagy, amyloidogenesis, and Alzheimer disease. J. Cell Sci. 120, 4081–4091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Li J., Kanekiyo T., Shinohara M., Zhang Y., Ladu M. J., Xu H., Bu G. (2012) Differential regulation of amyloid-β endocytic trafficking and lysosomal degradation by apolipoprotein E isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 44593–44601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sokolow S., Henkins K. M., Bilousova T., Miller C. A., Vinters H. V., Poon W., Cole G. M., Gylys K. H. (2012) AD synapses contain abundant Aβ monomer and multiple soluble oligomers, including a 56-kDa assembly. Neurobiol. Aging 33, 1545–1555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Cerf E., Gustot A., Goormaghtigh E., Ruysschaert J. M., Raussens V. (2011) High ability of apolipoprotein E4 to stabilize amyloid-β peptide oligomers, the pathological entities responsible for Alzheimer's disease. FASEB J. 25, 1585–1595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Petrlova J., Hong H. S., Bricarello D. A., Harishchandra G., Lorigan G. A., Jin L. W., Voss J. C. (2011) A differential association of apolipoprotein E isoforms with the amyloid-β oligomer in solution. Proteins 79, 402–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Koistinaho M., Lin S., Wu X., Esterman M., Koger D., Hanson J., Higgs R., Liu F., Malkani S., Bales K. R., Paul S. M. (2004) Apolipoprotein E promotes astrocyte colocalization and degradation of deposited amyloid-β peptides. Nat. Med. 10, 719–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Mandrekar S., Jiang Q., Lee C. Y., Koenigsknecht-Talboo J., Holtzman D. M., Landreth G. E. (2009) Microglia mediate the clearance of soluble Aβ through fluid phase macropinocytosis. J. Neurosci. 29, 4252–4262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Basak J. M., Verghese P. B., Yoon H., Kim J., Holtzman D. M. (2012) Low density lipoprotein receptor represents an apolipoprotein E-independent pathway of Aβ uptake and degradation by astrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 13959–13971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Thal D. R. (2012) The role of astrocytes in amyloid β-protein toxicity and clearance. Exp. Neurol. 236, 1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Vekrellis K., Ye Z., Qiu W. Q., Walsh D., Hartley D., Chesneau V., Rosner M. R., Selkoe D. J. (2000) Neurons regulate extracellular levels of amyloid β-protein via proteolysis by insulin-degrading enzyme. J. Neurosci. 20, 1657–1665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wirths O., Bayer T. A. (2012) Intraneuronal Aβ accumulation and neurodegeneration. Lessons from transgenic models. Life Sci. 91, 1148–1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Deane R., Sagare A., Hamm K., Parisi M., Lane S., Finn M. B., Holtzman D. M., Zlokovic B. V. (2008) ApoE isoform-specific disruption of amyloid β peptide clearance from mouse brain. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 4002–4013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Bachmeier C., Beaulieu-Abdelahad D., Crawford F., Mullan M., Paris D. (2013) J. Mol. Neurosci., 48, 270–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Hawkes C. A., Sullivan P. M., Hands S., Weller R. O., Nicoll J. A., Carare R. O. (2012) Disruption of arterial perivascular drainage of amyloid-β from the brains of mice expressing the human APOE ϵ4 allele. PloS ONE 7, e41636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Hong S., Quintero-Monzon O., Ostaszewski B. L., Podlisny D. R., Cavanaugh W. T., Yang T., Holtzman D. M., Cirrito J. R., Selkoe D. J. (2011) Dynamic analysis of amyloid β-protein in behaving mice reveals opposing changes in ISF versus parenchymal Aβ during age-related plaque formation. J. Neurosci. 31, 15861–15869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Basak J. M., Kim J., Pyatkivskyy Y., Wildsmith K. R., Jiang H., Parsadanian M., Patterson B. W., Bateman R. J., Holtzman D. M. (2012) Measurement of apolipoprotein E and amyloid β clearance rates in the mouse brain using bolus stable isotope labeling. Mol. Neurodegeneration 7, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Sadowski M. J., Pankiewicz J., Scholtzova H., Mehta P. D., Prelli F., Quartermain D., Wisniewski T. (2006) Blocking the apolipoprotein E/amyloid-β interaction as a potential therapeutic approach for Alzheimer's disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 18787–18792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Morris J. C., Selkoe D. J. (2011) Recommendations for the incorporation of biomarkers into Alzheimer clinical trials. An overview. Neurobiol. Aging 32, S1–S3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Cramer P. E., Cirrito J. R., Wesson D. W., Lee C. Y., Karlo J. C., Zinn A. E., Casali B. T., Restivo J. L., Goebel W. D., James M. J., Brunden K. R., Wilson D. A., Landreth G. E. (2012) ApoE-directed therapeutics rapidly clear β-amyloid and reverse deficits in AD mouse models. Science 335, 1503–1506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Lefterov I., Bookout A., Wang Z., Staufenbiel M., Mangelsdorf D., Koldamova R. (2007) Expression profiling in APP23 mouse brain. Inhibition of Aβ amyloidosis and inflammation in response to LXR agonist treatment. Mol. Neurodegeneration 2, 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Terwel D., Steffensen K. R., Verghese P. B., Kummer M. P., Gustafsson J. Å., Holtzman D. M., Heneka M. T. (2011) Critical role of astroglial apolipoprotein E and liver X receptor-α expression for microglial Aβ phagocytosis. J. Neurosci. 31, 7049–7059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Mahley R. W., Huang Y. (2012) Small-molecule structure correctors target abnormal protein structure and function. Structure corrector rescue of apolipoprotein E4-associated neuropathology. J. Med. Chem. 55, 8997–9008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.