Background: We propose that Na/K-ATPase regulates Src in an E1/E2 conformation-dependent manner.

Results: Expression of α1 mutants defective in E1/E2 transition altered both basal and stimuli-induced Src regulation.

Conclusion: Na/K-ATPase is necessary for dynamic regulation of Src and Src-mediated pathways.

Significance: This is the first demonstration that E1/E2 transition-defective mutants can affect both pumping and signaling functions of Na/K-ATPase.

Keywords: Integrin; Mutant; Na,K-ATPase; Signaling; Src

Abstract

The α1 Na/K-ATPase possesses both pumping and signaling functions. Using purified enzyme we found that the α1 Na/K-ATPase might interact with and regulate Src activity in a conformation-dependent manner. Here we further explored the importance of the conformational transition capability of α1 Na/K-ATPase in regulation of Src-related signal transduction in cell culture. We first rescued the α1-knockdown cells by wild-type rat α1 or α1 mutants (I279A and F286A) that are known to be defective in conformational transition. Stable cell lines with comparable expression of wild type α1, I279A, and F286A were characterized. As expected, the defects in conformation transition resulted in comparable degree of inhibition of pumping activity in the mutant-rescued cell lines. However, I279A was more effective in inhibiting basal Src activity than either the wild-type or the F286A. Although much higher ouabain concentration was required to stimulate Src in I279A-rescued cells, extracellular K+ was comparably effective in regulating Src in both control and I279A cells. In contrast, ouabain and extracellular K+ failed to produce detectable changes in Src activity in F286A-rescued cells. Furthermore, expression of either mutant inhibited integrin-induced activation of Src/FAK pathways and slowed cell spreading processes. Finally, the expression of these mutants inhibited cell growth, with I279A being more potent than that of F286A. Taken together, the new findings suggest that the α1 Na/K-ATPase may be a key player in dynamic regulation of cellular Src activity and that the capability of normal conformation transition is essential for both pumping and signaling functions of α1 Na/K-ATPase.

Introduction

Na/K-ATPase, or Na+ pump, is a ubiquitously expressed integral membrane protein, transporting Na+ and K+ across the plasma membrane by hydrolyzing ATP (1). It is essential for eukaryotic cells to maintain ionic homeostasis as well as to provide transmembrane Na+ gradients for the Na+-dependent transport of nutrients. Recent studies from different laboratories have revealed several new functions of the Na/K-ATPase that are dependent on its interaction with membrane, structural, and cytosolic proteins (2, 3). We have reported that the α1 Na/K-ATPase interacts with Src kinase. Moreover, it appears that the Na/K-ATPase·Src complex could act as a functional receptor for cardiotonic steroids to activate protein kinase cascades (4–6). Using in vitro binding assays, we have identified a pair of interacting domains that seems to be essential for the formation of this functional receptor. One is between the second cytoplasmic domain (CD2) of the Na/K-ATPase α1 subunit and Src SH2 domain, and the other is between the nucleotide (N) binding domain of α1 subunit and Src kinase domain. The latter interaction keeps Src in an inactive state. Binding of cardiotonic steroids such as ouabain to the Na/K-ATPase disrupts the latter interaction, resulting in an activation of the pump-associated Src (6). Besides Src, the α1 Na/K-ATPase has many interacting partners including phosphoinositide 3-kinase, inositol triphosphate receptor, adducin, ankyrin, and caveolin-1 and is actively involved in multiple cellular processes such as intracellular Ca2+ regulation and caveolae formation (3, 7–12).

It is known that the Na/K-ATPase exists in two major conformations, namely E1 and E2 (13). The fact that ouabain stabilizes the pump at the E2P state and consequently activates Src led us to speculate that the α1 Na/K-ATPase may interact with Src in a conformation-dependent manner. This postulation seems to be consistent with our recent studies (14). In the cell-free system, purified Na/K-ATPase stabilized in the E1 state with N-ethylmaleimide was capable of keeping Src in an inactive state, whereas Na/K-ATPase stabilized in the E2P state with fluoride compound stimulated Src. Moreover, we found that trypsinized or chymotrypsinized Na/K-ATPase in which the coordinated domain movements during the conformational transition were disrupted failed to respond to ouabain stimulation. Finally, we demonstrated that accumulation of E2 Na/K-ATPase by lowering extracellular K+ was sufficient to activate Src in LLC-PK1 cells.

Prior studies have identified many α1 mutants that inhibit the E1/E2 conformational transition by favoring the pump at either E1- or E2-like state (15–18). These mutants exhibit altered pumping properties. To further test the role of E1/E2 transition in Na/K-ATPase-mediated regulation of Src, we constructed vectors expressing either I279A or F286A rat α1 mutant and generated stable cell lines expressing the mutant. Prior studies showed that I279A mutation accumulated the pump at the E1 state, whereas F286A mutation increased the E2 state Na/K-ATPase. Moreover, these two mutants are from the same transmembrane domain (17). Finally, these two mutants produce more pronounced kinetic changes than most of the other mutants (17). Functional studies of these mutant-expressing cell lines demonstrate that inhibition of conformation transition is sufficient to attenuate the capability of Na/K-ATPase to regulate cellular Src and consequently ligand-induced activation of protein kinase cascades in cultured cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Polyclonal anti-Na/K-ATPase β1 and α1 antibodies were from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY); monoclonal anti-α-tubulin was from Sigma. Monoclonal anti-α1 antibody (α6F) was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank at the University of Iowa. Polyclonal rat α1-specific antibody (anti-NASE) was provided by Dr. Thomas Pressley (Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX). Polyclonal anti-pFAK, polyclonal anti-pAkt, and polyclonal anti-Akt were purchased from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). Monoclonal anti-caveolin-1, monoclonal anti-FAK, monoclonal anti-Src antibody, polyclonal anti-ERK1/2 antibody, monoclonal anti-pERK1/2 antibody, goat anti-rabbit, and goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The polyclonal anti-Tyr(P)-418 Src and Image-iT FX signal enhancer was purchased from Invitrogen. Antifade kit, Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody, and Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody were from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Radioactive 86Rb+ was from PerkinElmer Life Science Products. The QuikChange mutagenesis kit was purchased from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). EZ-link NHS-SS-biotin and streptavidin-agarose beads were from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA). Other chemicals of the highest purity were all obtained from Sigma.

Cell Culture

Cells used in this work were all derived from LLC-PK1 cells that were originally from ATCC. The generation of α1 knockdown PY-17 cells and the rat α1-rescued PY-17 cells (called AAC-19) were done as previously described (5). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 10% FBS (14). After cells reached 95–100% confluence, they were serum-starved overnight and used for experiments unless indicated otherwise.

Site-directed Mutagenesis and the Generation of Mutant-rescued Stable Cell Lines

Site-directed mutagenesis of rat α1 subunit (I279A or F286A, numbered according to the GenBankTM accession number NM_01254) was performed by the QuikChange mutagenesis kit using pRc/CMV-α1 AACm1 vector as a template (5). The pRc/CMV- α1 AACm1 carries silent mutations that prevent the binding of α1-specific siRNA to the transcript of rat α1 mRNA (5). The mutants were verified by DNA sequencing. To generate stable cell lines, the α1 knockdown PY-17 cells were transfected with different vectors expressing either I279A or F286A α1 mutant using Lipofectamine 2000 as previously described (5). The cells were then selected with ouabain (3 μm) 24 h after transfection. The ouabain-resistant colonies were isolated and expanded into stable cell lines. Cells were then cultured in the absence of ouabain for three generations before being used for the experiments (5).

Immunoblot Analysis

The immunoblot analysis was performed according to the previous protocol (14). After indicated treatment, cells were solubilized in modified ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation buffer containing 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, 1 mm NaF, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 150 mm NaCl, and 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4. Cell lysates were then centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 15 min. Supernatants were collected, and protein content was measured. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to an Optitran membrane, and blotted by specific antibodies.

Confocal Fluorescence Microscope

The imaging studies were conducted as previously described (14). Cells were seeded on coverslips until they reached 90% confluence. The cells were then fixed with pre-chilled (−20 °C) methanol for 15 min. The fixed cells were blocked with either PBS containing 1% FBS for 30 min (for analyzing total α1 Na/K-ATPase) or Image-iT Max Signal Enhancer (for Src Tyr(P)-418) on ice and incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C followed by washing and incubation with Alexa- Fluor conjugated secondary antibody. The stained cells on coverslips were washed, mounted, and then visualized using a Leica DMIRE2 microscope (Wetzlar, Germany).

Ouabain-sensitive Na/K-ATPase Activity

The Na+/K+ ATPase activity was assayed according to the protocol previously described (5) with modification. Cells were harvested in Skou C buffer (30 mm histidine, 250 mm sucrose, 1 mm EDTA, pH 7.4) and briefly sonicated. After centrifugation (800 × g for 10 min), the post-nuclear fraction was further centrifuged (100,000 × g for 45 min) to get crude membrane. The crude membrane pellet was resuspended in Skou C buffer and treated with alamethicin (0.1 mg/mg of protein) for 10 min at room temperature. The preparation was then incubated in the buffer containing 20 mm Tris (pH 7.2), 1 mm EGTA, 3 mm MgCl2, 20 mm KCl, 100 mm NaCl, 5 mm NaN3, and 2 mm ATP. Phosphate generated during the ATP hydrolysis was measured by BIOMOL GREEN reagent (Enzo Life Science). Ouabain-sensitive Na/K-ATPase activities were calculated as the difference between the presence and absence of 5 mm ouabain.

Ouabain-sensitive 86Rb+ Uptake Activity

The transport function of Na/K-ATPase was assessed by measuring the ouabain-sensitive uptake of the K+ congener, 86Rb+, as described (19) with minor modification. Cells were cultured in 12-well plates to >90% confluence and serum-starved overnight before experiment. The cells were washed and incubated in culture medium with or without 5 mm ouabain over 10 min at 37 °C. 86Rb+ (1μCi/well) was added for 10 min at 37 °C, and the reaction was stopped by washing with ice-cold 0.1 m MgCl2. The cells were incubated in 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) for 45 min, and TCA-soluble 86Rb+ was counted in a Beckman scintillation counter. TCA-precipitated proteins were dissolved by 0.1 n NaOH, 0.2% SDS solution, and the concentration was determined using the Lowry protein assay. All counts were normalized to protein amount.

[3H] Ouabain Binding

To measure the surface expression of the endogenous pig Na/K-ATPase, [3H]ouabain binding assay was performed as described (20). Cells were cultured in 12-well plates until confluent and serum-starved overnight. Afterward, the cells were incubated in K+-free Krebs solution (142.4 mm NaCl, 2.8 mm CaCl2, 0.6 mm NaH2PO4, 1.2 mm MgSO4, 10 mm glucose, 15 mm Tris, pH 7.4) for 15 min and then exposed to 200 nm [3H]ouabain for 30 min at 37 °C. After incubation, the cells were washed 3 times with ice-cold K+-free Krebs solution, solubilized in 0.1 m NaOH-0.2% SDS, and counted in a scintillation counter for [3H]ouabain. Nonspecific binding was measured in the presence of 1 mm unlabeled ouabain and subtracted from total binding. All counts were normalized to protein amount.

Cell Surface Biotinylation and Streptavidin Precipitation

Biotinylation assay was conducted according to Liang et al. (19). Cells were cultured on 60-mm Petri dishes until they reach 90% confluence. The cells were then rinsed twice with ice-cold PBS (137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 10 mm Na2HPO4, 2 mm KH2PO4, pH 7.4) and incubated with 2 ml of NHS-SS-biotin (1.5 mg/ml) freshly dissolved into biotinylation buffer (10 mm triethanolamine, pH 9.0, 150 mm NaCl) for 25 min at 4 °C on a gently shaking rocker. Cells were rinsed twice with PBS containing 100 mm glycine and incubated in the same buffer for 20 min at 4 °C to quench the unreacted biotin. Cells were then washed twice with PBS and solubilized in 400 μl of lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 50 mm Tris, pH 7.5) for 60 min on a rocker with gentle motion. Cell lysates were collected by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 min. Cell lysates (250 μg) were incubated overnight with 150 μl of streptavidin-agarose beads in lysis buffer with a total volume of 800 μl at 4 °C with end-over-end rotation. The pellet was collected, rinsed, resuspended in 50 μl of Laemmli loading buffer, and subject to Western blot analysis.

Cell Counting Assay

Cell growth was measured as previously described (20). Cells were seeded at a density of 20,000/well in 12-well plates in DMEM containing 10% FBS. At the indicated time point, cells were trypsinized, stained by trypan blue, and trypan blue-negative cells were counted.

Cell Spreading Assay

Cell spreading was assayed according to Richardson et al. (22). After cells were trypsinized, 200,000 cells were seeded in a 60-mm-diameter dish that contained 4 ml prewarmed DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells were then allowed to spread for the indicated time points at 37 °C. For each experiment, five random fields were photographed. A total of at least 300 cells were counted for each experiment condition. Spreading cells were defined as those that had extended processes, lacked a rounded morphology, and were not phase bright.

Cell Spreading-associated Kinase Activity Assay

The assay was performed according to Schlaepfer and Hunter (23). Cells were grown up to 90% confluence and serum-starved with DMEM + 0.5% FBS for 24 h. Dishes (10 cm) were coated overnight with 10 μg/ml fibronectin (in PBS) at 4 °C on a shaker. On the day of the experiment the dishes were incubated in serum-free media at 37 °C incubator for 1 h. Cells were harvested using 0.05% trypsin, 0.53 mm EDTA, and trypsin was neutralized by adding 0.5 mg/ml of soybean trypsin inhibitor in PBS. The cells were then washed, suspended in serum-free medium, and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Cells (6 millions) were plated in the prewarmed dishes and allowed to attach/spread for different times. At the indicated time points, dishes were removed from incubator, and cell lysates were collected and subject to Western blot.

Cell Volume Measurement

Cells were plated in six-well plates and serum-starved when they reached 95–100% confluence. Cells were then trypsinized and resuspended, and cell volume was measured in a Beckman Z2 Coulter Counter (Fullerton, CA).

Immunoprecipitation

To assay for Na/K-ATPase α1 binding to Src, the immunoprecipitation assay was performed as previously described (24). Briefly, cell lysates were incubated with monoclonal anti-Src antibody overnight and then protein G-agarose for 2 h. After extensive washes, immunoprecipitates were subject to Western blot analysis.

RESULTS

Construction of Cell Lines Stably Expressing I279A and F286A α1 Na/K-ATPase Mutants

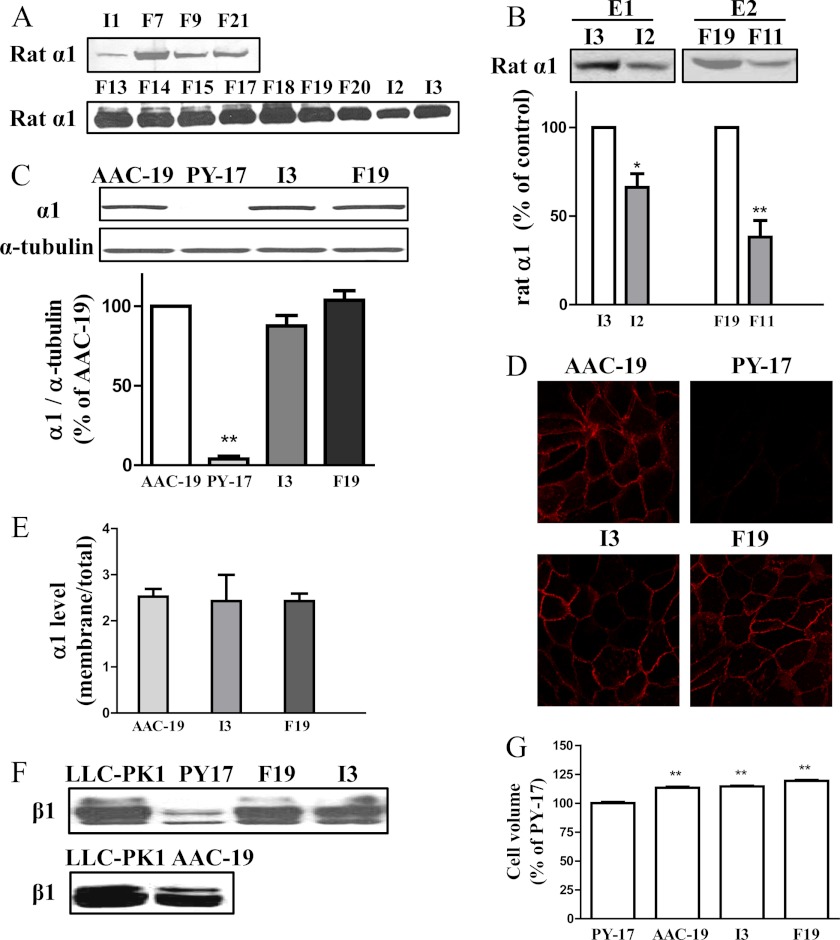

To reduce the interference from endogenous α1 Na/K-ATPase, we transfected α1 knockdown PY-17 cells. PY-17 cells were derived from LLC-PK1 cells, and the expression of endogenous α1 Na/K-ATPase was reduced more than 90% by the expression of an α1-specific siRNA (5). Wild-type rat-α1 rescued PY-17 cells (AAC-19) were used as a control (5). Although transfection of PY-17 cells with F286A mutant, like wild-type α1 (5), resulted in numerous clones (F7, F9, F13-F15, F17-F21), I279A mutant only produced three clones in the presence of ouabain (I1, I2, and I3) (Fig. 1A). In general, the level of F286A mutant expression appeared to be higher than that of I279A mutant in the rescued cells as revealed by Western blot (Fig. 1A). Among the three I279A clones, clone number 3 (LY-I279A-3 cells, abbreviated as I3) expressed the highest amount of mutant α1 (Fig. 1A). Further analyses of cell lysates from different clones revealed that the expression of I279A in I3 cells was similar to that in clone number 19 (LY-F286A-19 cells, abbreviated as F19) from F286A mutant-transfected cells (Fig. 1B). Moreover, total α1 in these cells was comparable to that in the control AAC-19 cells (Fig. 1C). Consistently, confocal imaging analyses showed comparable expression of membrane α1 in all three rescued cell lines (Fig. 1D). Finally, surface biotinylation analyses confirmed that the ratio of surface biotinylable α1 to total α1 was similar among these cell lines (Fig. 1E).

FIGURE 1.

Expression of I279A and F286A mutant α1 in stable cell lines. Panels A and B, the expression of mutant rat α1 Na/K-ATPase in different cell lines was detected by Western blot using rat α1-specifc polyclonal antibody. Panel C, total cellular α1 (mutant plus endogenous) Na/K-ATPase in different cell lines was measured by Western blot using a monoclonal antibody that recognizes both pig and rat α1. Panel D, cells were cultured on coverslips and immunostained with the monoclonal anti-α1 antibody, showing that the majority of expressed α1 (both α1 mutant and endogenous) is in or close to the plasma membrane. Panel E, the ratio of biotinylable α1 Na/K-ATPase over total α1 Na/K-ATPase in indicated cell lines. Cells were biotinylated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The same volume of the bound fraction and total cell lysates was analyzed by Western blot. Panel F, the expression of β1 in different cell lines was detected by Western blot. Panel G, shown is a comparison of cell volume of different cells. Cells were trypsinized, and the volume of floating cells was measured. A representative Western blot of at least three repeats is shown and the quantitative data are the mean ± S.E. from at least three experiments. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus control (Student's t test).

Na/K-ATPase Activity in I279A and F286A Mutant-rescued Cells

To characterize the functionality of the mutant Na/K-ATPase, we first checked the β1 subunit expression. As shown in Fig. 1F, expression of either mutant was able to rescue the expression and glycosylation of β1 as did wild-type α1. These findings indicate that the expressed mutant α1 is fully capable of assembling with the β1 subunit into a functional Na/K-ATPase.

To assess the pumping capability of these mutants, we measured ouabain-sensitive ATPase activity in crude membrane preparations made from different cell lines. As depicted in Table 1, the Na/K-ATPase activity in I3 and F19 cells was about half of that in AAC-19 cells. To further test the pumping capacity of these rescued cell lines, ouabain-sensitive 86Rb+ uptake was determined. As shown in Table 1, I3 and F19 cells exhibited 49 and 53% ouabain-sensitive 86Rb+ uptake in comparison to that of AAC-19 cells, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Na/K-ATPase activity and 86Rb+ uptake in different cells

Cells were cultured until they reach 100% confluence, and ATPase activity as well as the 86Rb+ uptake activity was measured as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The values are the mean ± S.E. from at least three independent experiments.

| Cell lines | AAC-19 | I3 | F19 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pump activity/α1 (%) n ≥ 3 | 100 | 42 ± 7 | 50 ± 4 |

| Rb+ uptake activity/mg protein (%) n ≥ 3 | 100 | 49 ± 4 | 53 ± 3 |

Because ouabain dissociates from rat α1 Na/K-ATPase very rapidly (25, 26), we used [3H]ouabain binding assay to estimate the number of endogenous α1 Na/K-ATPase in different cell lines. As shown in Table 2, the endogenous pig α1 in the mutant-expressing cells was less than that in PY-17 cells, about 67% of the PY-17 cells in mutant cells. Because PY-17 cells expressed less than 10% of α1 Na/K-ATPase compared with that in control AAC-19 cells (5), it is therefore concluded that >90% of α1 expressed in the mutant-rescued cells was from mutant rat α1 cDNA.

TABLE 2.

Ouabain binding sites in different cell lines

Cells were cultured until they reached 100% confluence, and the ouabain binding site was measured as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The values are the mean ± S.E. from at least three independent experiments.

| Cell lines | PY-17 | I3 | F19 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ouabain binding sites (%) | 100 ± 4 | 67 ± 6 | 67 ± 6 |

To verify that the E1/E2 transition was inhibited in the mutant-rescued cells, vanadate-dependent Na/K-ATPase activity was measured. As reported (17), vanadate sensitivity of cell lysates from I3 cells was significantly reduced in comparison to that of AAC-19 cells, whereas a large increase was noted in F19 cells (data not shown).

Because ion pumping function was compromised in the mutant-expressing cell lines, cell volume could be altered. Therefore, we measured cell volume in PY-17, AAC-19, I3, and F19 cells. Surprisingly, PY-17 cells had the smallest volume (Fig. 1G). Expression of mutant α1 was as effective as that of wild-type α1 in restoration of cell volume, and no difference in cell volume was detected in I3 and F19 cells (Fig. 1G).

Taken together, the above findings indicate that expression of mutants restored total cellular α1 Na/K-ATPase in I3 and F19 cells to the level comparable to that in AAC-19 cells and that the expressed α1 Na/K-ATPase displayed a defect in E1/E2 conformational transition, resulting in an inhibition of pumping activity in these cells in comparison to that in AAC-19 cells. However, the pumping activities in the I3 and F19 cells were much higher than that of parental PY-17 cells (19).

Regulation of Src and Src Effectors by Mutant α1

We reported that the number of α1 Na/K-ATPase in the plasma membrane is close to 1 million/cell in LLC-PK1 cells (19). To estimate the potential capacity of α1 Na/K-ATPase-mediated Src regulation in these cells, we made a semiquantitative measurement of the number of Src in these cells by Western blot analyses of cell lysates and the known amount of purified Src (data not shown). We estimated that there are about 2 × 105 Src per LLC-PK1 cell on average.

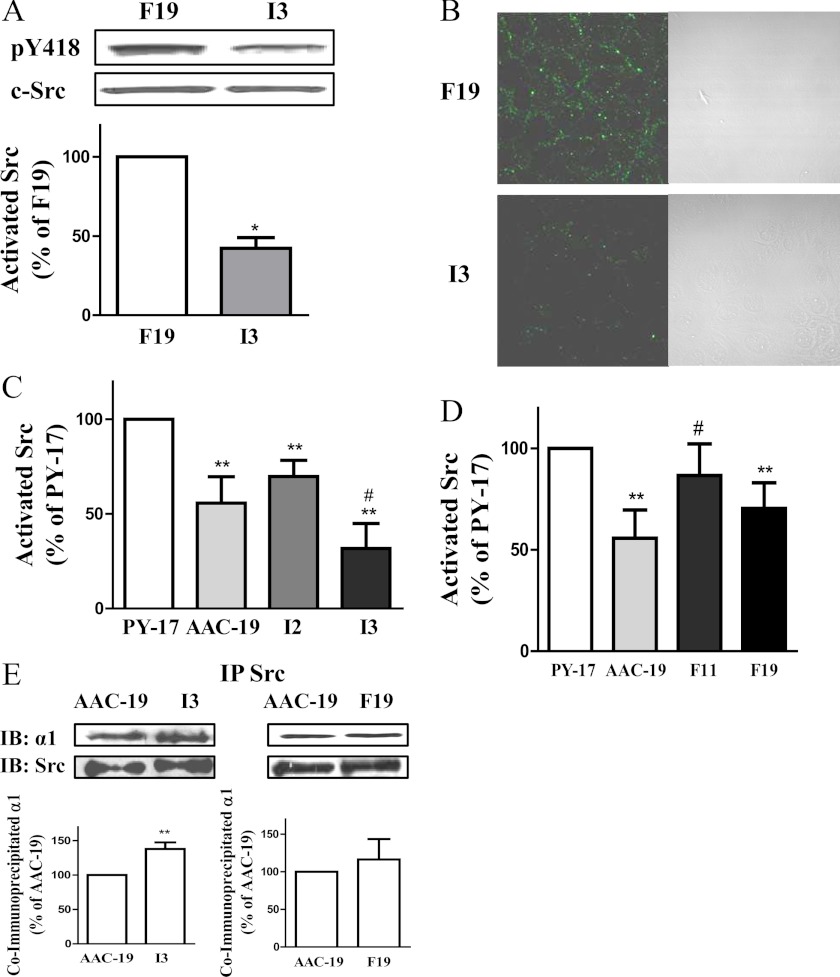

Our previous studies suggest that the α1 Na/K-ATPase may regulate Src in a conformation-dependent manner in LLC-PK1 cells (14). If the α1 Na/K-ATPase could regulate Src in these cells, we expect that Src activity would be different between I3 and F19 cells, although they express a similar number of Na/K-ATPase. Indeed, when the activity of Src was measured by Western blot analysis of Tyr-418 phosphorylation (Tyr(P)-418), basal active Src in I3 cells was <50% that in F19 cells (Fig. 2A). Total Src per mg protein in I3 cells was similar to that in F19 cells (97% ± 4 of F19, n = 4). To verify these findings and to visualize the distribution of active Src in these cells, we immunostained I3 and F19 cells with anti-Tyr(P)-418 antibody. As depicted in Fig. 2B, more active Src resided in the plasma membrane area in F19 cells than that in I3 cells.

FIGURE 2.

Regulation of basal Src activity by the expressed mutants. Panel A, total cell lysates collected from F19 and I3 cells were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blot for Src Tyr(P)-418 (pY418) and total Src. A representative Western blot is shown, and the quantitative data are the mean ± S.E. from at least three independent experiments. Panel B, cells were cultured on coverslips and immunostained with anti-Src Tyr(P)-418 antibody. Representative images from three separate experiments are shown. Panel C and D, total cell lysates collected from different cell lines were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blot for Tyr(P)-418 Src and total Src. The quantitative data are the mean ± S.E. from at least three independent experiments. **, p < 0.01 versus PY-17; #, p < 0.01 versus AAC-19 (Student's t test). Panel E, shown is Src binding to the α1 Na/K-ATPase. Lysates from different cell lines were immunoprecipitated (IP) with an anti-Src antibody and probed for Src and α1 Na/K-ATPase. A representative Western blot (IB) is shown, and the quantitative data are the mean ± S.E. from at least three independent experiments. **, p < 0.01(Student's t test).

To further assess whether the expression of I279A mutant could indeed inhibit cellular Src, we compared Src activity in Na/K-ATPase knockdown PY-17, rat α1-rescued AAC-19, and I279A mutant-rescued I2 and I3 cells. As we previously reported (5), knockdown of α1 Na/K-ATPase increased basal Src activity in PY-17 cells, and the expression of wild-type rat α1 reduced the basal Src activity in AAC-19 cells (Fig. 2C). Similarly, expression of I279A mutant α1 reduced cellular Src activity in a mutant α1 amount-dependent manner. Although a similar amount of the α1 was expressed in I3 and AAC-19 cells, cellular Src activity was significantly lowered in I3 cells, suggesting that the increased accumulation of I279A mutant in the E1-like state may consequently be more effective in keeping cellular Src in an inactive state. This notion is further supported by the fact that although I2 cells expressed less α1 (about 60%, Fig. 1B) than that of AAC-19 cells, they had the comparable basal Src activity as that in AAC-19 cells (Fig. 2C).

When the same set of experiments was conducted to assess F286A mutant-mediated regulation of cellular Src activity, we found that the basal Src activity in F19 cells was significantly reduced from that in PY-17 cells (Fig. 2D). Moreover, there was no statistical difference in Src activity between F19 and AAC-19 cells, although on average it was a bit higher in F19 cells. To be sure, we repeated the experiments in F11 cells that express less F286A mutant α1. As shown in Fig. 2D, basal Src activity in F11 cells was similar to that of PY-17 cells but much higher than that in AAC-19 cells.

To be sure that the expressed mutants were capable of interacting with Src, the same amount of cell lysates from different cell lines was subject to immunoprecipitation using monoclonal anti-Src antibody. As depicted in Fig. 2E, the mutant α1 was also capable of interacting with Src. Although there was no detectable difference between AAC-19 and F19 cells, a significant increase in Src/Na/K-ATPase interaction was observed in I3 cells.

Taken together, the above data indicate that I279A α1, an E1-like mutant, interacts and produces more inhibition of cellular Src activity than that of F286A α1, an E2-like mutant. Because I3 and F19 express similar levels of rat α1 and have the same pumping capacity but different regulation of cellular Src activity, the following studies were conducted mainly in these cell lines to assess how expression of mutant α1 Na/K-ATPase defective in conformational transition affects Src-mediated signal transduction.

Expression of I279A and F286A Mutants Alters Ouabain- and Low Extracellular K+-induced Signal Transduction

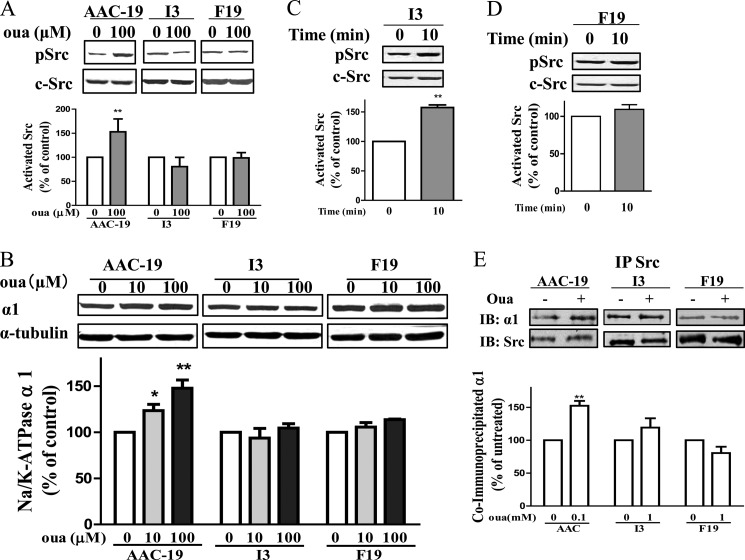

Ouabain is a specific agonist of α1 Na/K-ATPase·Src complex (4). Binding of ouabain to the α1 Na/K-ATPase stimulated Src within minutes and increased the expression of α1 Na/K-ATPase in hours (5, 20). Indeed, these changes in response to ouabain (100 μm) were observed in the control AAC-19 cells (Fig. 3, A and B). It is important to note that AAC-19 cells express ouabain-insensitive rat α1 Na/K-ATPase. Therefore, μm instead of nm ouabain was used (5).

FIGURE 3.

Effects of ouabain on mutant cells. Panel A, cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of ouabain for 10 min. Cell lysates were collected and subject to Western blot analysis for Src Tyr(P)-418/total Src. Panel B, cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of ouabain for 24 h, collected, and probed for total α1 by Western blot. Panel C and D, I3 and F19 cells were treated with 1 mm ouabain for 10 min, harvested, and probed for Src Tyr(P)-418/total Src. Panel E, lysates from untreated or ouabain-treated cells were immunoprecipitated (IP) with an anti-Src antibody and probed for Src and α1 Na/K-ATPase. A representative Western blot (IB) is shown, and the quantitative data are the mean ± S.E. from at least three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 (Student's t test).

To assess whether inhibition of E1 to E2 transition was sufficient to alter ouabain-induced signal transduction, we repeated these studies in I3 cells. As depicted in Fig. 3A, in contrast to what we observed in AAC-19 cells (5), up to 100 μm ouabain failed to stimulate Src in I3 cells. Similarly, the same concentrations of ouabain showed no effect on the expression of α1 Na/K-ATPase in I3 cells (Fig. 3B). Because the inhibition of E1 to E2 transition reduces ouabain binding affinity to the α1 Na/K-ATPase (17), the above defect in ouabain-induced signal transduction could be overcome by adding more ouabain if the I279A mutant is capable of binding and forming a functional receptor with Src. To test this postulation, we exposed I3 cells to 1 mm ouabain for 10 min and measured active Src. Based on the published data (17), 1 mm ouabain should produce more than 50% inhibition of I279A mutant, comparable to that induced by 100 μm ouabain in AAC-19 cells. As depicted in Fig. 3C, 1 mm ouabain produced significant stimulation of Src in I3 cells.

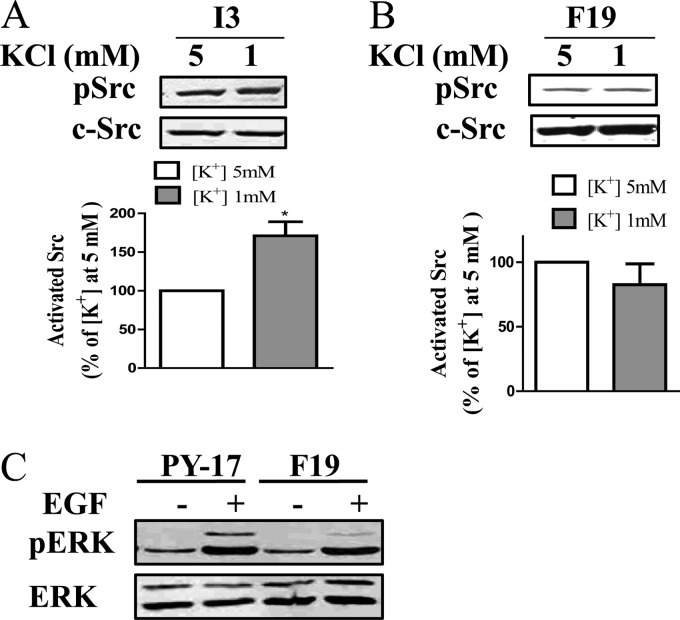

Extracellular K+ promotes E2 to E1 conformation transition, and lowering extracellular K+ is known to accumulate α1 Na/K-ATPase in E2 conformation (27). We previously showed that decreasing extracellular K+ activated Src through the Na/K-ATPase in AAC-19 cells (14). Interestingly, when the effect of lowering extracellular K+ on Src was measured in I3 cells, we found that 1 mm extracellular K+ was able to produce a modest stimulation of Src (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Effects of low K+ and EGF on mutant cells. Panel A and B, confluent cells were incubated in medium containing 1 mm K+. Total cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blot for Src Tyr(P)-418 and total Src. Panel C, confluent cells were serum-starved for 12 h and treated with EGF (10 ng/ml). Total cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blot for pERK and total ERK. A representative Western blot is shown, and the quantitative data are the mean ± S.E. from at least three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 (Student's t test).

To compare and contrast, we repeated the above experiments in F19 cells. Unlike I3 cells, we failed to detect any stimulation of Src by ouabain even up to 1 mm in F19 cells (Fig. 3D). Moreover, low K+ had no effect on the kinases either (Fig. 4B). Although it is unlikely, to be sure that signal transduction in general was not compromised in F19 cells, we exposed these cells to EGF and measured for ERK activation. As shown in Fig. 4C, EGF was able to stimulate ERK in both PY-17 and F19 cell lines. These findings suggest that F286A mutant is less able to assemble with Src into a functional receptor. This suggestion is consistent with the fact that F286A mutant is less effective in inhibiting the basal Src than that of I279A mutant (Fig. 2).

We showed that stimulation of Src by ouabain led to the recruitment of more Src to the receptor complex (24). This was also the case in AAC-19 cells where ouabain (100 μm) increased the amount of α1 co-precipitated with Src (Fig. 3E). However, when the same experiments were repeated in I3 and F19 cells, ouabain (1 mm) failed to increase the interaction (Fig. 3E).

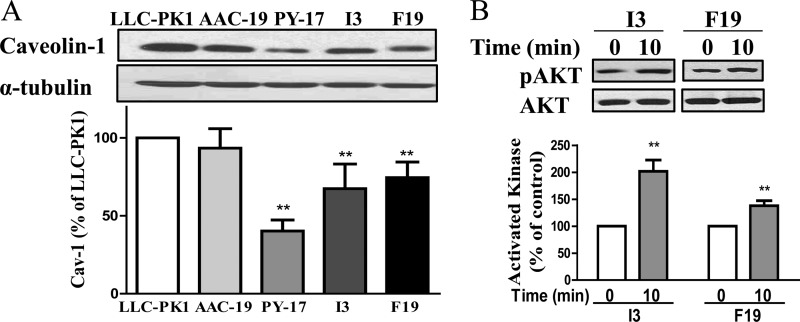

Expression of Mutant α1 Produces a Partial Restoration of Caveolin-1 Expression and Allows Ouabain to Activate Akt

We showed that knockdown of α1 Na/K-ATPase increased the endocytosis and degradation of caveolin-1 (10). Because caveolae plays an important role in ouabain-induced signal transduction, we probed caveolin-1 in different cell lines. As depicted in Fig. 5A, although expression of wild-type α1 fully rescued the expression of caveolin-1 in AAC-19 cells, both I279A and F286A mutants produced a partial restoration of caveolin-1 expression in I3 and F19 cells. Thus, changes in caveolin-1 expression could not account for the difference between I3 and F19 cells in response to ouabain and low K+ stimulation.

FIGURE 5.

Effects of mutant α1 on caveolin-1 expression and Akt pathway. Panel A, confluent cells were serum-starved and harvested. Total cell lysates collected from different cell lines were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blot for caveolin-1 and α-tubulin (loading control). Panel B, I3 and F19 cells were treated with 1 mm ouabain for 10 min, harvested, and analyzed by Western blot for pAkt and total Akt. A representative Western blot is shown, and the quantitative data are the mean ± S.E. from at least three independent experiments. **, p < 0.01 (Student's t test).

In addition to the Src/ERK pathway, ouabain is known to stimulate the PI3K/Akt pathway in renal epithelial cells and other types of cells (11). To further compare and contrast I3 and F19 cells, we measured the effect of 1 mm ouabain on Akt in these cell lines. As depicted in Fig. 5B, ouabain was able to stimulate Akt in both cell lines. However, the effect of ouabain on Akt was much higher in I3 than that of F19 cells.

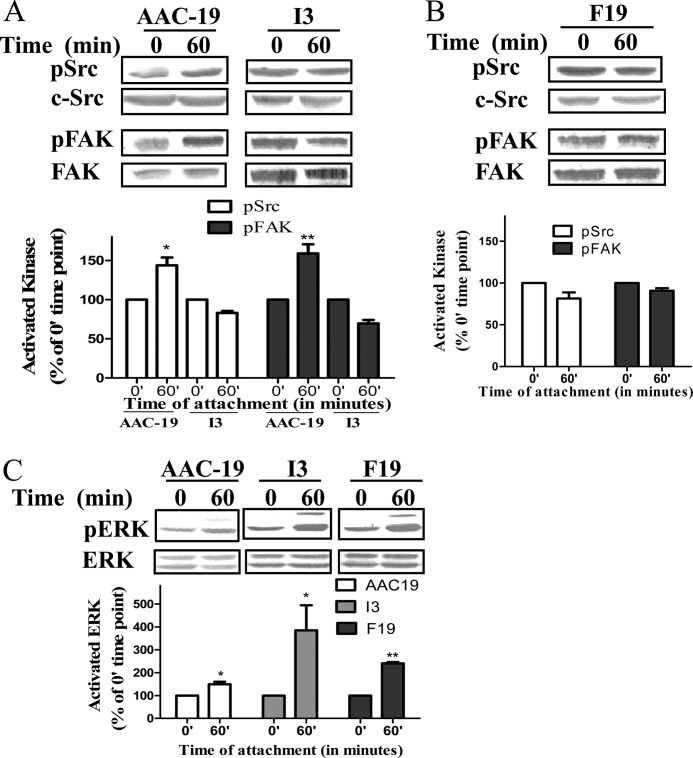

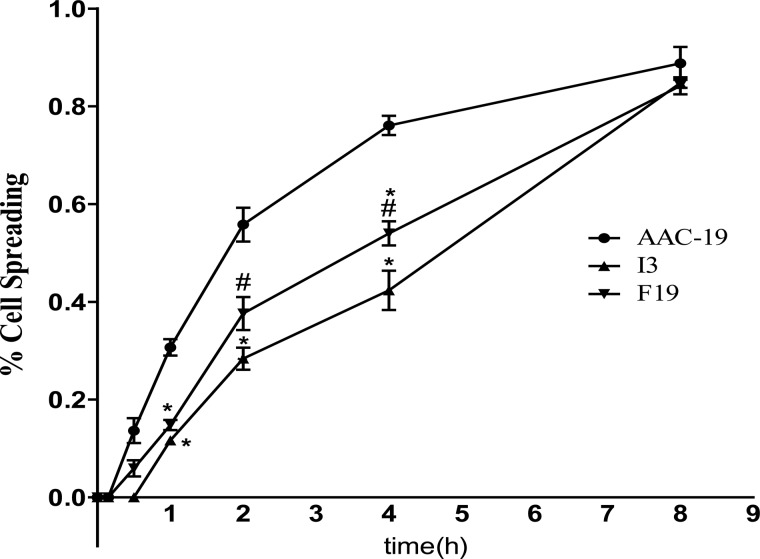

Expression of I279A and F286A Mutants Attenuates the Ability of Cells to Regulate Cellular Functions Using Src-mediated Signal Transduction

Src is known to play an important role in cell attachment and spreading (28–30). Because the expression of I279A α1 Na/K-ATPase inhibits cellular Src activity, we looked at whether I279A is capable of attenuating signal transduction pathways activated by cell attachment. As shown in Fig. 6A, plating AAC-19 cells caused a significant activation of Src and FAK in 60 min. However, when I3 cells were plated, no activation was observed. Consistently, when time-dependent cell spreading was analyzed, we found that expression of I279A greatly slowed down cell spreading (Fig. 7). For example, about 45% inhibition in spreading was observed at the 4-h time point. Interestingly, when the same experiments were done in F19 cells where basal Src was higher than that in I3 cells and cell spreading was also inhibited but to a lesser degree (Fig. 7). For example, only 30% inhibition was recorded in F19 after 4 h of platting, which was significantly less than the inhibition detected in I3 cells. Moreover, cell attachment-induced activation of Src and FAK was also inhibited in F19 cells as in I3 cells (Fig. 6B). It is important to note that not every kinase pathway associated with cell attachment was inhibited in mutant-expressing cell lines. When ERK was probed, we saw the activation of ERK in all three cell lines (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

Effects of mutant α1 on integrin-induced signaling pathway. Cells were plated and collected as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Total cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blot for Src Tyr(P)-418/total Src, p576/577 FAK/total FAK, and pERK/total ERK. A representative Western blot is shown, and the quantitative data are the mean ± S.E. from at least three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 (Student's t test).

FIGURE 7.

Inhibition of cell spreading by the expression of mutant α1. Cells were plated on 60-mm dishes for the indicated time points, and phase-contrast images were photographed as described under “Experimental Procedures”. The number of spread cells was counted, and the values are the mean ± S.E. from at least three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus AAC-19; #, p < 0.05 versus I3 (Student's t test).

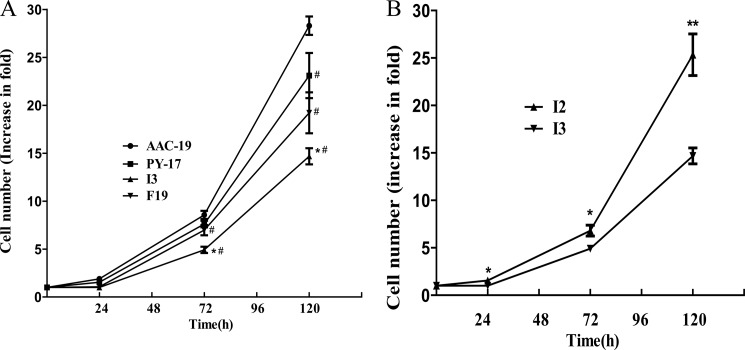

Expression of I279A and F286A Mutants Inhibits Cell Growth

Because Src-mediated pathways are known to play an important role in cell proliferation, we cultured cells in full medium and counted the number of cells at different time points. As shown in Fig. 8A, expression of either F286A or I279A caused a significant inhibition of cell growth. Moreover, when compared between the two mutant-expressing cell lines, the growth of I3 cells was much slower than that of F19 cells. To be sure this inhibition is not due to the defect in pumping activity, we also measured cell growth of PY-17 cells. As depicted in Fig. 8A, even F19 cells grew slower than PY-17 cells. To be sure that the inhibition is due to the expression of mutant α1, we compared proliferation rate of I2 and I3, showing that I2 cells, expressing less I279A, grew much faster than that of I3 (Fig. 8B).

FIGURE 8.

Effects of mutant α1 expression on cell growth. Panel A, shown are growth curves of different cell lines. AAC-19, PY-17, I3, and F19 cells were plated in 12-well plates (20,000 cells/well), cultured for different periods of time, then collected and counted as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The values are the mean ± S.E. from four independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus F19 cells; #, p < 0.05 versus AAC-19 cells. Panel B, shown is a comparison of I2 cell growth with that of I3 cells. Growth curves of these two cell lines were constructed as in Fig. 8A. The values are the mean ± S.E. from at least three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 (Student's t test).

DISCUSSION

In this study we have assessed the effects of two mutant α1 defective in conformational transition on cellular Src and Src-related signal transduction in cultured cells. Our new findings suggest the following. First, the α1 Na/K-ATPase could regulate Src in a conformation-dependent manner. Second, this regulation plays an important role in turning on/off of Src-related signal transduction. Finally, mutations that alter the conformational transition of α1 Na/K-ATPase compromise not only the pumping but also the signaling function of Na/K-ATPase.

Regulation of Src by the α1 Na/K-ATPase

PY-17 cells express about 10% α1 Na/K-ATPase in comparison with that in the parental LLC-PK1 cells (5). We showed previously that transfection of PY-17 cells with expression vectors carrying either wild-type rat α1 or mutant α1 cDNAs could restore the α1 Na/K-ATPase to the level comparable with that of LLC-PK1 cells. Moreover, the expression of endogenous pig α1 was kept at 10% or less (10). This appears to be the case with the mutant-rescued cells (Table 2). Both mutants (I279A and F286A) were expressed and assembled with the β subunit (Fig. 1F). In general, the expressed I279A and F286A mutants exhibited enzymatic properties similar to those reported previously (17). Although I279A had much lower vanadate sensitivity, F286A mutant was more sensitive to vanadate than the wild-type α1. Because the mutants have defects in conformational transition, the expressed mutants had lower turnover rates. It is important to note that our expression system is different from the commonly used mammalian expression system (e.g. HeLa and OK cells) in several ways. First, the endogenous α1 in HeLa or OK cells is ∼50% of total α1 Na/K-ATPase. Second, most assays have to be conducted in the presence of a low dose of ouabain (e.g. 10 μm) to eliminate the contribution from the endogenous α1 Na/K-ATPase when the parental HeLa or OK cells were used for expression analyses. Although this could work for the analyses of membrane preparations, it would compromise the interpretation of experimental findings when studies were conducted in live cells because the binding of ouabain to the endogenous α1 not only inhibits the pumping function but could also activate the signaling function of this pool of Na/K-ATPase.

The clue suggesting the α1 Na/K-ATPase·Src interaction came from our early studies of ouabain-induced protein tyrosine phosphorylation (4). These studies demonstrated that ouabain activated Src by stimulating the phosphorylation of Tyr-418 and that the activation of Src was required for ouabain-induced transactivation of EGF receptors and many other protein kinase and lipase cascades (4, 8, 31). Subsequently, we and others have found that the α1 Na/K-ATPase and Src co-localized in the plasma membrane and that they could be co-immunoprecipitated from cell lysates. Moreover, fluorescence resonance energy transfer analyses indicated that both proteins were in close proximity, supporting a direct interaction in live cells (6). These early observations have now been confirmed by many laboratories (32–38). More recently, we have identified two potential interacting pairs between the α1 subunit of Na/K-ATPase and Src, namely the A domain/SH2 domain and the N domain/kinase domain. Functionally, the latter interaction keeps Src in an inactive state (5, 6). Peptide mapping led to the identification of a 20-amino acid peptide (NaKtide) from the N domain of α1 subunit that binds and inhibits Src (39). In accordance, we showed that knockdown of α1 Na/K-ATPase increased the content of active Src and that rescuing the knockdown cells by either wild type, a pump-null mutant of α1 subunit, or the addition of pNaKtide (a cell permeable NaKtide derivative) was sufficient to reduce the elevated cellular Src activity (5, 39).

According to the literature, most of regulators affect the catalytic activity of Src by modulating its intramolecular associations, either the interaction between Src SH2 domain and phosphorylated Tyr-529 in the C-terminal tail or between the SH3 domain and the linker connecting the SH2 and the kinase domain (40). For example, activation of phosphatase SHP2 dephosphorylates Tyr-529 and abrogates SH2/C terminus association, which leads to the increment of Src activity (41). Similarly, Sin binds to the SH3 domain and activates Src (42). There are also stimulators (i.e. activated FAK) that abolish both intramolecular associations (43).

In comparison, the Na/K-ATPase-mediated Src regulation is quite unique. There is about a 5-fold more α1 Na/K-ATPase than that of Src in renal epithelial cells according to our estimation. Because most of α1 Na/K-ATPase resides in the plasma membrane in these cells, the α1 Na/K-ATPase could represent an important mechanism of Src regulation, especially in the compartment of plasma membrane. This is consistent with what we have published (5, 6, 14, 39) and with the new findings presented in Figs. 2 and 3.

The α1 Na/K-ATPase could provide several different ways for the cell to dynamically regulate Src. First, the α1 Na/K-ATPase could function as a negative regulator of Src because of its interaction with the Src kinase domain. This is evident as the expression of pump-null mutant α1 or application of pNaKtide inhibits Src in the Na/K-ATPase knockdown cells (5, 39). Interestingly, Ma et al. (44) showed that G-proteins also bind to the Src kinase domain. However, unlike the α1 Na/K-ATPase, this binding led to the activation of Src.

Second, the α1 Na/K-ATPase could bind Src in a conformation-dependent manner. This mode of regulation provides cells a dynamic on/off mechanism of Src regulation. Our new findings provide further support to this notion. For example, the E1-like mutant I279A was more potent than the wild-type α1 and the E2-like mutant F286A in attenuating basal Src activity in PY-17 cells (Fig. 2). In addition, I279A mutant is still capable of forming a functional receptor for low K+ to activate Src in I3 cells (Fig. 4).

Uncertainties and Implications

Although our new findings suggest that the α1 Na/K-ATPase may regulate Src in E1/E2 conformation-dependent manner, it is noteworthy to mention several uncertainties. First, we only tested two α1 Na/K-ATPase mutants. Many mutations of α1 subunit affecting E1/E2 equilibrium have been identified (15–17, 45–47). It is important to test other mutants to verify the above findings and to identify mutant-specific defects in signal transduction. Moreover, although it is less likely, some of the defects in signal transduction associated with the expression of I279A and F286A could be related to the reduced pumping function of both mutants. Thus, it would be more desirable to find a mutant α1 that pumps normally but has a defect in Src regulation.

Second, although the expression of F286A mutant, a vanadate-sensitive E2-like mutant, regulates Src differently from that of I279A mutant or wild-type α1, it did not cause an increase in Src activity as predicted by our working model (14) (Figs. 2–4). As shown in Fig. 2, expression of this E2-like mutant actually reduced the cellular Src activity in PY-17 cells, although much less effectively than that of I279A. Clearly, more studies are needed to produce a better model to explain Na/K-ATPase-mediated Src regulation. However, several possibilities should be considered. First, although this mutant is more sensitive to vanadate, it is highly resistant to ouabain as the I279A mutant (17). According to the published data, F286A mutant has an increased rate of E2P to E2(K2) conversion (17). Because the ouabain-bound E2P conformation is different from that of E2(K2) (48), it is possible that ouabain-bound E2P represents the most optimal state of Src activation among different E2 conformations (49, 50). Second, the fact that ouabain and low K+ failed to stimulate Src in F19 cells suggests that F286A mutant could only interact with either Src kinase domain or SH2 domain. This mode of interaction would reduce the number of functional receptor complex if both A domain/SH2 and N domain/kinase domain interactions are required for the formation of a functional receptor complex.

It has been suggested that mutations in α2 and α3 Na/K-ATPase might contribute to neuronal diseases such as familial hemiplegic migraine type 2 (FHM2), sporadic hemiplegic migraine, rapid-onset dystonia parkinsonism, and bipolar disorder (21, 51–57). Interestingly, several mutants identified in FHM2 patients such as R202Q and T263M shifted E1/E2 transition in favor of E1 as illustrated by the lower E1P-E2P conversion and the accumulation of more E1 over E2 (57). Moreover, R689Q and M731T have also been found to favor the E1 form as evidenced by their insensitivity to vanadate (54). Although the fundamental pathological mechanism for the FHM2 has not been clarified, our findings imply that the change in E1/E2 equilibrium by these mutations not only affects the pumping but may also affect the signaling function of Na/K-ATPase. Thus, it would be important to test whether the α2 Na/K-ATPase in the brain shares the same signaling function as the α1 Na/K-ATPase in the kidney.

Ouabain is known to stimulate several signaling pathways other than Src. It is of interest to note that although I279A and F286A mutants were defective in Src signaling, they could still conduct the PI3K/Akt pathway. These findings indicate a different mechanism of PI3K/Akt regulation by the Na/K-ATPase.

In short, this work taken together with our prior reports reveals that the α1 Na/K-ATPase is an important Src regulator. Mutations that affect conformational transition of Na/K-ATPase could disturb normal cell functions by attenuating Src-mediated signal transduction. On the other hand, the formation of Na/K-ATPase·Src complex might enable a dynamic on/off mechanism of Src regulation through the equilibrium of E1/E2 conformation, which could be achieved via multiple ways such as changes in the concentrations of ligands and the expression, targeting, and the assembly of the complex. This dynamic regulatory mechanism is not only important for the signaling through the Na/K-ATPase ligands but may also for integrin and other pathways where Src is a key signal transducer.

Footnotes

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-36573 and HL-109015 (NHLBI) and GM-78565 (NIGMS).

REFERENCES

- 1. Lingrel J. B., Kuntzweiler T. (1994) Na+,K+-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 19659–19662 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Li Z., Xie Z. (2009) The Na/K-ATPase/Src complex and cardiotonic steroid-activated protein kinase cascades. Pflugers Arch. 457, 635–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aperia A. (2007) New roles for an old enzyme. Na,K-ATPase emerges as an interesting drug target. J. Intern. Med. 261, 44–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haas M., Askari A., Xie Z. (2000) Involvement of Src and epidermal growth factor receptor in the signal-transducing function of Na+/K+-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 27832–27837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liang M., Cai T., Tian J., Qu W., Xie Z. J. (2006) Functional characterization of Src-interacting Na/K-ATPase using RNA interference assay. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 19709–19719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tian J., Cai T., Yuan Z., Wang H., Liu L., Haas M., Maksimova E., Huang X. Y., Xie Z. J. (2006) Binding of Src to Na+/K+-ATPase forms a functional signaling complex. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 317–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ferrandi M., Salardi S., Tripodi G., Barassi P., Rivera R., Manunta P., Goldshleger R., Ferrari P., Bianchi G., Karlish S. J. (1999) Evidence for an interaction between adducin and Na+-K+-ATPase. Relation to genetic hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. 277, H1338–H1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen Y., Cai T., Yang C., Turner D. A., Giovannucci D. R., Xie Z. (2008) Regulation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor-mediated calcium release by the Na/K-ATPase in cultured renal epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 1128–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen Y., Cai T., Wang H., Li Z., Loreaux E., Lingrel J. B., Xie Z. (2009) Regulation of intracellular cholesterol distribution by Na/K-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 14881–14890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cai T., Wang H., Chen Y., Liu L., Gunning W. T., Quintas L. E., Xie Z. J. (2008) Regulation of caveolin-1 membrane trafficking by the Na/K-ATPase. J. Cell Biol. 182, 1153–1169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu L., Zhao X., Pierre S. V., Askari A. (2007) Association of PI3K-Akt signaling pathway with digitalis-induced hypertrophy of cardiac myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 293, C1489–C1497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nelson W. J., Veshnock P. J. (1987) Ankyrin binding to (Na+ + K+)ATPase and implications for the organization of membrane domains in polarized cells. Nature 328, 533–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jorgensen P. L., Hakansson K. O., Karlish S. J. (2003) Structure and mechanism of Na,K-ATPase. Functional sites and their interactions. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 65, 817–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ye Q., Li Z., Tian J., Xie J. X., Liu L., Xie Z. (2011) Identification of a potential receptor that couples ion transport to protein kinase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 6225–6232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Toustrup-Jensen M., Vilsen B. (2003) Importance of conserved Thr-214 in domain A of the Na+,K+ -ATPase for stabilization of the phosphoryl transition state complex in E2P dephosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 11402–11410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Toustrup-Jensen M., Vilsen B. (2005) Interaction between the catalytic site and the A-M3 linker stabilizes E2/E2P conformational states of Na+,K+-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 10210–10218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Toustrup-Jensen M., Vilsen B. (2003) Functional consequences of alterations to Ile-279, Ile-283, Glu-284, His-285, Phe-286, and His-288 in the NH2-terminal part of transmembrane helix M3 of the Na+,K+-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 38653–38664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Toustrup-Jensen M., Vilsen B. (2002) Importance of Glu-282 in transmembrane segment M3 of the Na+,K+-ATPase for control of cation interaction and conformational changes. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 38607–38617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liang M., Tian J., Liu L., Pierre S., Liu J., Shapiro J., Xie Z. J. (2007) Identification of a pool of non-pumping Na/K-ATPase. J. Biol.. Chem. 282, 10585–10593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tian J., Li X., Liang M., Liu L., Xie J. X., Ye Q., Kometiani P., Tillekeratne M., Jin R., Xie Z. (2009) Changes in sodium pump expression dictate the effects of ouabain on cell growth. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 14921–14929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Einholm A. P., Toustrup-Jensen M. S., Holm R., Andersen J. P., Vilsen B. (2010) The rapid-onset dystonia parkinsonism mutation D923N of the Na+,K+-ATPase α3 isoform disrupts Na+ interaction at the third Na+ site. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 26245–26254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Richardson A., Malik R. K., Hildebrand J. D., Parsons J. T. (1997) Inhibition of cell spreading by expression of the C-terminal domain of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) is rescued by coexpression of Src or catalytically inactive FAK. A role for paxillin tyrosine phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 6906–6914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schlaepfer D. D., Hunter T. (1997) Focal adhesion kinase overexpression enhances ras-dependent integrin signaling to ERK2/mitogen-activated protein kinase through interactions with and activation of c-Src. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 13189–13195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Haas M., Wang H., Tian J., Xie Z. (2002) Src-mediated inter-receptor cross-talk between the Na+/K+-ATPase and the epidermal growth factor receptor relays the signal from ouabain to mitogen-activated protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 18694–18702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Periyasamy S. M., Huang W. H., Askari A. (1983) Origins of the different sensitivities of (Na+ + K+)-dependent adenosinetriphosphatase preparations to ouabain. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 76, 449–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wallick E. T., Pitts B. J., Lane L. K., Schwartz A. (1980) A kinetic comparison of cardiac glycoside interactions with Na+,K+-ATPases from skeletal and cardiac muscle and from kidney. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 202, 442–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Akera T., Ng Y. C. (1991) Digitalis sensitivity of Na+,K+-ATPase, myocytes, and the heart. Life Sci. 48, 97–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sabe H., Hata A., Okada M., Nakagawa H., Hanafusa H. (1994) Analysis of the binding of the Src homology 2 domain of Csk to tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins in the suppression and mitotic activation of c-Src. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91, 3984–3988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schaller M. D., Hildebrand J. D., Shannon J. D., Fox J. W., Vines R. R., Parsons J. T. (1994) Autophosphorylation of the focal adhesion kinase, pp125FAK, directs SH2-dependent binding of pp60src. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 1680–1688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Webb D. J., Donais K., Whitmore L. A., Thomas S. M., Turner C. E., Parsons J. T., Horwitz A. F. (2004) FAK-Src signalling through paxillin, ERK, and MLCK regulates adhesion disassembly. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 154–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yuan Z., Cai T., Tian J., Ivanov A. V., Giovannucci D. R., Xie Z. (2005) Na/K-ATPase tethers phospholipase C and IP3 receptor into a calcium-regulatory complex. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 4034–4045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang Z., Zheng M., Li Z., Li R., Jia L., Xiong X., Southall N., Wang S., Xia M., Austin C. P., Zheng W., Xie Z., Sun Y. (2009) Cardiac glycosides inhibit p53 synthesis by a mechanism relieved by Src or MAPK inhibition. Cancer Res. 69, 6556–6564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Uddin M. N., Horvat D., Glaser S. S., Mitchell B. M., Puschett J. B. (2008) Examination of the cellular mechanisms by which marinobufagenin inhibits cytotrophoblast function. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 17946–17953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Khundmiri S. J., Amin V., Henson J., Lewis J., Ameen M., Rane M. J., Delamere N. A. (2007) Ouabain stimulates protein kinase B (Akt) phosphorylation in opossum kidney proximal tubule cells through an ERK-dependent pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 293, C1171–1180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Arnaud-Batista F. J., Costa G. T., Oliveira I. M., Costa P. P., Santos C. F., Fonteles M. C., Uchôa D. E., Silveira E. R., Cardi B. A., Carvalho K. M., Amaral L. S., Pôças E. S., Quintas L. E., Noël F., Nascimento N. R. (2012) The natriuretic effect of bufalin in isolated rat kidneys involves activation of the Na+/K+-ATPase-Src kinase pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 302, F959–F966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Karpova L. V., Bulygina E. R., Boldyrev A. A. (2010) Different neuronal Na+/K+-ATPase isoforms are involved in diverse signaling pathways. Cell Biochem. Funct. 28, 135–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nguyen A. N., Jansson K., Sánchez G., Sharma M., Reif G. A., Wallace D. P., Blanco G. (2011) Ouabain activates the Na-K-ATPase signalosome to induce autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease cell proliferation. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 301, F897–F906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zheng J., Koh X., Hua F., Li G., Larrick J. W., Bian J. S. (2011) Cardioprotection induced by Na+/K+-ATPase activation involves extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway. Cardiovasc. Res. 89, 51–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Li Z., Cai T., Tian J., Xie J. X., Zhao X., Liu L., Shapiro J. I., Xie Z. (2009) NaKtide, a Na/K-ATPase-derived peptide Src inhibitor, antagonizes ouabain-activated signal transduction in cultured cells. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 21066–21076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Brown M. T., Cooper J. A. (1996) Regulation, substrates, and functions of src. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1287, 121–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Peng Z. Y., Cartwright C. A. (1995) Regulation of the Src tyrosine kinase and Syp tyrosine phosphatase by their cellular association. Oncogene 11, 1955–1962 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Alexandropoulos K., Baltimore D. (1996) Coordinate activation of c-Src by SH3- and SH2-binding sites on a novel p130Cas-related protein, Sin. Genes Dev. 10, 1341–1355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Thomas J. W., Ellis B., Boerner R. J., Knight W. B., White G. C., 2nd, Schaller M. D. (1998) SH2- and SH3-mediated interactions between focal adhesion kinase and Src. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 577–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ma Y. C., Huang J., Ali S., Lowry W., Huang X. Y. (2000) Src tyrosine kinase is a novel direct effector of G proteins. Cell 102, 635–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Toustrup-Jensen M., Vilsen B. (2003) Importance of Thr-214 in the conserved TGES sequence of the Na+,K+-ATPase for vanadate binding and hydrolysis of E2P. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 986, 267–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vilsen B., Toustrup-Jensen M. (2003) Importance of transmembrane segment M3 of Na+,K+-ATPase for control of conformational changes and the cytoplasmic entry pathway for Na+. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 986, 50–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Einholm A. P., Toustrup-Jensen M., Andersen J. P., Vilsen B. (2005) Mutation of Gly-94 in transmembrane segment M1 of Na+,K+-ATPase interferes with Na+ and K+ binding in E2P conformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102, 11254–11259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yatime L., Laursen M., Morth J. P., Esmann M., Nissen P., Fedosova N. U. (2011) Structural insights into the high affinity binding of cardiotonic steroids to the Na+,K+-ATPase. J. Struct. Biol. 174, 296–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Olesen C., Picard M., Winther A. M., Gyrup C., Morth J. P., Oxvig C., Møller J. V., Nissen P. (2007) The structural basis of calcium transport by the calcium pump. Nature 450, 1036–1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Toyoshima C., Nomura H., Tsuda T. (2004) Lumenal gating mechanism revealed in calcium pump crystal structures with phosphate analogues. Nature 432, 361–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rodacker V., Toustrup-Jensen M., Vilsen B. (2006) Mutations F785L and T618M in Na+,K+-ATPase, associated with familial rapid-onset dystonia parkinsonism, interfere with Na+ interaction by distinct mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 18539–18548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Clapcote S. J., Duffy S., Xie G., Kirshenbaum G., Bechard A. R., Rodacker Schack V., Petersen J., Sinai L., Saab B. J., Lerch J. P., Minassian B. A., Ackerley C. A., Sled J. G., Cortez M. A., Henderson J. T., Vilsen B., Roder J. C. (2009) Mutation I810N in the α3 isoform of Na+,K+-ATPase causes impairments in the sodium pump and hyperexcitability in the CNS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 14085–14090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Morth J. P., Poulsen H., Toustrup-Jensen M. S., Schack V. R., Egebjerg J., Andersen J. P., Vilsen B., Nissen P. (2009) The structure of the Na+,K+-ATPase and mapping of isoform differences and disease-related mutations. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 364, 217–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Segall L., Mezzetti A., Scanzano R., Gargus J. J., Purisima E., Blostein R. (2005) Alterations in the α2 isoform of Na,K-ATPase associated with familial hemiplegic migraine type 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102, 11106–11111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kirshenbaum G. S., Clapcote S. J., Duffy S., Burgess C. R., Petersen J., Jarowek K. J., Yücel Y. H., Cortez M. A., Snead O. C., 3rd, Vilsen B., Peever J. H., Ralph M. R., Roder J. C. (2011) Mania-like behavior induced by genetic dysfunction of the neuron-specific Na+,K+-ATPase α3 sodium pump. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 18144–18149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kirshenbaum G. S., Saltzman K., Rose B., Petersen J., Vilsen B., Roder J. C. (2011) Decreased neuronal Na+,K+-ATPase activity in Atp1a3 heterozygous mice increases susceptibility to depression-like endophenotypes by chronic variable stress. Genes Brain Behav. 10, 542–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Schack V. R., Holm R., Vilsen B. (2012) Inhibition of phosphorylation of Na+,K+-ATPase by mutations causing familial hemiplegic migraine. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 2191–2202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]