Abstract

Background

To reduce study start-up time, increase data sharing, and assist investigators conducting clinical studies, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke embarked on an initiative to create common data elements for neuroscience clinical research. The Common Data Element Team developed general common data elements which are commonly collected in clinical studies regardless of therapeutic area, such as demographics. In the present project, we applied such approaches to data collection in Friedreich ataxia, a neurological disorder that involves multiple organ systems.

Methods

To develop Friedreich’s ataxia common data elements, Friedreich’s ataxia experts formed a working group and subgroups to define elements in: Ataxia and Performance Measures; Biomarkers; Cardiac and Other Clinical Outcomes; and Demographics, Laboratory Tests and Medical History. The basic development process included: Identification of international experts in Friedreich’s ataxia clinical research; Meeting via teleconference to develop a draft of standardized common data elements recommendations; Vetting of recommendations across the subgroups; Dissemination of recommendations to the research community for public comment.

Results

The full recommendations were published online in September 2011 at http://www.commondataelements.ninds.nih.gov/FA.aspx. The Subgroups’ recommendations are classified as core, supplemental or exploratory. Template case report forms were created for many of the core tests.

Conclusions

The present set of data elements should ideally lead to decreased initiation time for clinical research studies and greater ability to compare and analyze data across studies. Their incorporation into new and ongoing studies will be assessed in an ongoing fashion to define their utility in Friedreich’s ataxia.

Keywords: Cerebellum, dorsal root ganglion, mitochondrion, clinical measure, NINDS Common Data Elements

Friedreich ataxia (FRDA) is an autosomal recessive disorder associated with progressive ataxia, scoliosis and cardiomyopathy that affects about 1 in 30,000 Caucasians (1–2). Some patients also develop diabetes mellitus, and insulin resistance is a common feature of the disorder (3–6). FRDA is caused by mutations in the FXN gene, with 97% of patients having GAA repeat expansions in the first intron on both alleles of the FXN gene. This results in decreased expression of the mitochondrial protein frataxin by affecting chromatin structure at the FXN locus (7). Reduced frataxin expression impairs mitochondrial iron-sulfur-cluster (ISC) biogenesis, resulting in deficits of multiple ISC-containing enzymes and altered iron homeostasis with accumulation of iron in the mitochondrial matrix (8–9). Impaired function of ISC-containing respiratory chain complexes (complex I, II and III) leads to increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can react with the excess redox-active iron in the mitochondria to generate toxic free radicals (10). This biochemical understanding of the disorder has allowed the identification of potential therapeutic targets, leading to the development of experimental treatments for the disease. These include: 1) drugs that increase frataxin levels by acting on the altered chromatin structure induced by the expanded GAA repeats (11); 2) drugs upregulating frataxin by other mechanisms (12); 3) drugs with antioxidant and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS)-promoting properties (13–16); 4) iron chelators targeting the abnormal intracellular iron distribution that occurs in FRDA (17); 5) drugs stimulating mitochondrial function and oxidative metabolism (18). Concomitantly, clinical research has moved forward at a rapid pace, including execution of later stage clinical trials. In spite of the relative rarity of FRDA, at least 12 agents are in various stages of pre-clinical and clinical development for FRDA at the present time, showing the speed with which advancement is occurring (19–20).

Such advancement has brought new challenges to clinical investigators, some of whom are also newcomers to the field. The design, execution and interpretation of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in FRDA are as complex as for any other chronic neurodegenerative disease. They require the development or adaptation and validation of clinical rating scales and of other clinical evaluation tools, including functional and quality of life assessments, the discovery and validation of biomarkers, and reliable data on natural history. Major initiatives to this end are ongoing in North America/Australia (the Cooperative Clinical Research Network in Friedreich Ataxia- CCRN-FA) and Europe (European Friedreich Ataxia CTS- EFACTS) in the form of prospective studies of large series of patients. The results of these studies, together with the experience gained from several RCTs in FRDA that have been performed in recent years, form the basis of the recommendations of the data that should be collected in future RCTs. Defining these data items is essential to maximize the power of an RCT to provide meaningful clinical information. Furthermore, if clinical investigators around the world agree on a common set of data elements to be collected in clinical trials, this will facilitate multicenter studies and allow meta-analyses. Multicenter collaborative studies are a necessity when dealing with a rare disease with only a limited number of affected individuals who can be followed at any single clinical site. The National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke (NINDS) has launched an initiative to create common data elements (CDEs) for neuroscience clinical research and thus reduce study start-up time, increase data sharing, and assist investigators conducting clinical studies (although they are not yet meant as clinical management tools). The NINDS CDE Team (NCT) has developed general CDEs, which are commonly collected in clinical studies regardless of therapeutic area, such as demographics and adverse events. In addition to general CDEs, the NCT has also worked with experts in a variety of specific disorders such as epilepsy, stroke, traumatic brain injury and Parkinson’s disease to design disease specific common data elements (21 –24). In the present work, this collaborative group sought to use the CDE initiative to support the development of CDEs for FRDA. This has been the first experience of developing CDEs for a less common multisystem disease with different challenges to data harmonization.

Methods

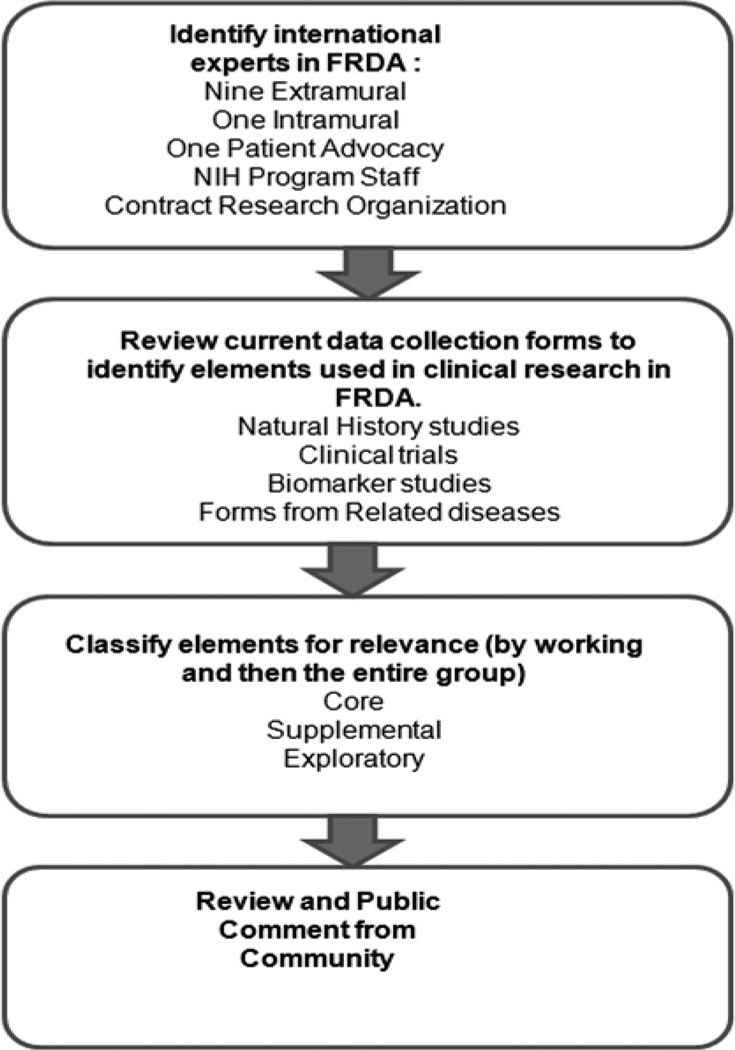

To develop CDEs for FRDA, a Working Group (WG) was formed, and directed to focus on elements in the following domains: Demographics and Medical History, Ataxia and Performance Measures; Cardiac and Clinical Outcomes; and Biomarkers and Laboratory Tests. The basic CDE development process included the following steps (Figure 1):

Identifying international experts in FRDA clinical research for the WG: Individuals were recruited from extramural academic centers (nine), NIH intramural researchers (one), patient advocacy groups (one), and NIH program officers (two). The group contained 7 neurologists, 4 cardiologists, one geneticist, and one genetic counselor. The overall group contained the principal investigators from the American/ Australian and the European natural history study. Most individual experts participated in more than one topic WG. The invited clinicians and scientist were supported by a contracted clinical research organization, KAI Research Inc. (Rockville, MD), who scheduled WG conference calls and provided administrative support on action items such as development of the CDE data dictionaries based on the WG recommendations.

-

Reviewing current data collection forms to identify elements used in clinical research: Each group met via teleconference and reviewed available items from existing natural history studies and other clinical research in FRDA as well as CDE forms developed for other diseases, and selected items for further use. These items were classified by each WG for their role in final CDEs.

There rwere three categories of CDEs:- Core CDE - Used by the vast majority of FA studies, strongly encouraged for use in a study;

- Supplemental CDE - Used by a significant number of FA studies, not as crucial to have in a study compared to core CDEs;

- Exploratory CDE - Used by some FA studies and is important enough to be included in the CDEs. These items were then evaluated for relevance and classification by the entire working group, followed by public comment from the research community.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the CDE development process.

In final form each CDE was presented by its:

CDE Name

Definition / Description

Code List / Permissible Values (which describe the standard way the CDE should be coded)

Definitions for Codes / Permissible Values (which further define the code list / permissible values)

Additional Comments / Special Instructions (Other important information about the CDE that will help ensure it is collected consistently)

Classification (Core, supplemental, Exploratory)

References

In addition, CRFs for the CDEs were created when possible.

Results

Overall features of FRDA CDEs

The full CDE details were published online in September 2011 at http://www.commondataelements.ninds.nih.gov/FA.aspx. This included a Catalog of 373 FRDA CDEs with detailed specifications for each CDE; a Library of 21 customizable case report form (CRF) modules; a List of approximately 27 standardized instruments with explanations of when each instrument is recommended for use; and a summary of the instrument’s strengths and weaknesses, and additional references. An overview of their development is presented here.

As FRDA is a multisystem disease containing features both within and outside the domain of clinical neurology, the working groups focused on the practical definition of a core CDE for this situation. Core elements selected were those that are present in the majority of individuals with FRDA and are linked to measures of disease severity and progression. The WG designated as few tests/data elements as core as possible in the interest of reducing the burden of data collection but balanced with need to have the minimal data set to be meaningful for both individual and comparative studies. Overall, based on the interpretation of a core CDE being used in almost all, if not all clinical research studies (including both interventional and non interventional studies), the group designated relatively few tests/data elements as core items. However, it was readily recognized that items that are essential for neurological studies might not be needed for cardiological studies. Consequently, only 6 items were identified as core CDEs for neurologic measures. In contrast, 22 ECG, 31 echocardiographic, and 7 Holter elements were felt to be core items, but only for studies directly addressing cardiac issues. As no laboratory testing is clearly relevant to all studies in FRDA, laboratory core elements were few, and directed to sample collection and storage issues crucial for systematic analysis across studies (reference reviews showing few biomarkers). The FRDA CDEs also included 6 core elements from demographic and social status, 27 from medical history, 11 vital sign core CDEs, 9 from activities of daily living and gait, and 5 cardiac outcome core elements. Thus the total number of core elements is 95 fewer than that created for several other neurologic disorders (Table 1).

Table 1.

Core and Total CDEs in FRDA by Sub-domain

| Sub-Domain | Form Name | Number of Core Elements |

Number of Total Elements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Demographics and Social Status |

6 | 21 |

| General Health History |

Adult Medical History and Prior Health Status |

27 | 60 |

| Pediatric Medical History |

0 | 31 | |

| Family History | 2 | 5 | |

| Medication History | 6 | 16 | |

| Behavior and Social History |

3 | 21 | |

| Vital Signs and Other Body Measures |

Vital Signs | 11 | 18 |

| Laboratory and Biospecimens/ Biomarkers |

Laboratory Tests | 6 | 13 |

| Plasma Collection | 0 | 10 | |

| Urine Collection | 0 | 7 | |

| Imaging Diagnostics (Cardiac) |

Cardiac and Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

0 | 5 |

| Non-Imaging Diagnostics (Cardiac) |

Electrocardiogram | 22 | 22 |

| Echocardiogram | 31 | 31 | |

| Holter Exam | 7 | 7 | |

| Data Source and Reliability |

Data Source and Reliability |

0 | 6 |

| Activities of Daily Living/ Performance |

Activities of Daily Living and Gait |

9 | 31 |

| Clinical Event End Points (Cardiac) |

Cardiac End Points | 5 | 5 |

Specific CDE groups

-

Demographics and Medical History: The development of FRDA CDEs for the general information of demographic and medical history started with available CDEs from previous NINDS CDE projects, as well as the medical history and related forms form the ongoing FRDA natural history studies. Many of the eventual CDEs matched those used in others diseases, but some focused on specific FRDA-related elements. The demographic core elements contained those relevant to any disease study as well as CDEs directed to neurologic issues, such as handedness. The medical history was substantially more focused on FRDA specific issues. In this group, core items included detailed results of the genetic test performed to confirm the diagnosis and its methodology, neurologic and first symptom onset, ambulation status, speech abilities, cardiac evaluations and status of scoliosis and diabetes. The CRFs provided derive from the ongoing natural history studies in FRDA. Supplemental items generally amplified specific aspects of the history, and were felt more appropriate for studies testing more directed hypotheses.

The CDEs also contained other aspects of medical history. Interestingly, while FRDA has an early onset, all history items relevant to prenatal, perinatal or neonatal events were designated as exploratory, reflecting the neurodegenerative rather than neurodevelopmental perspective on the disorder. Further history related CDEs emphasized as core elements those components of family history, medication history, and social history directly related to the neurologic, cardiac and diabetic features of FRDA.

Ataxia and performance measures: The subgroup focused on the existing ataxia rating scales, their relative level of validation, and those that are likely to be most useful. Core items (n=6) included use of at least one of the validated ataxia scales (FARS, SARA, ICARS) (25–28) as well as use of performance measures, particularly the timed 25-foot walk and 9 hole pegboard, and a targeted activities of daily living measure (29–32). In standard clinical studies, such a group of CDEs would allow one to capture all of the primary neurologic features of the disease from both a subjective and objective perspective. Quality of life scales were considered as supplemental, as were many speech measures, based on the high level of detail in such measures. Other exercise based measures, bladder function scales, detailed hand and leg function, and the Tardieu scale for motor tone were felt to be exploratory, in need of either further validation or more suitable for target studies to each of these systems.

-

Cardiac and Clinical Outcomes: As the cardiomyopathy of FRDA remains the major cause of mortality, cardiac testing CDEs were perceived as core items for clinical research studies in FRDA. Standard ECG, echocardiogram and Holter CDEs were felt to be core CDEs for any study addressing cardiac issues in FRDA. In contrast, although cardiac MRI may be the most sensitive test for many crucial items in the research assessment of FRDA, its relative lack of availability and potential issues in reliability in multisite studies were felt to prevent it being identified as a core CDE (33–34). Thus, it was viewed as supplemental.

Although many of the above measures (particularly ataxia measures or performance measures) are likely to be registration level endpoints for clinical trials, the CDE process identified some specific core endpoints. These included the SF36, which is well validated in FRDA, the FRDA specific activities of daily living scale (ADL), which is also included in the quantified neurological exam designated the FARS, and cardiac endpoints based on staging of CHF and hospitalization (35–37). Each of these is directly useful as clinical outcome measures for phase III studies.

Biomarkers and Laboratory Tests: At present there is a lack of easily utilized biomarkers and uniform laboratory abnormalities for FRDA. Consequently, it was felt most crucial to develop standard operating procedures (SOPs) to lower the variability of lab testing, such as precise dating, detailed identification of samples, and handling protocols. Using these as core CDEs (rather than specific test elements) would allow later interpretation and validation of laboratory abnormalities if identified, and ensure that such results would not reflect artifactual associations. Supplemental laboratory CDEs include tests to evaluate some functions in detail, both to assess the general health of the patient and to explore some potential FRDA-related abnormalities, e.g. in glucose metabolism, markers of cardiac damage, markers of oxidative stress, etc.

Discussion

The NINDS CDE project has focused on harmonization of data collection within different diseases in order to facilitate research initiation, data collection, and analysis. Such harmonization will also be particularly useful in meta-analyses combining the results from different studies. The present CDE recommendations in FRDA join analogous recommendations from stroke, epilepsy, traumatic brain injury, Parkinson’s disease, spinal cord injury, and congenital muscular dystrophy (21–24).

Compared with the process for other diseases, creation of the CDEs for FRDA was facilitated by a variety of existing resources. First, the existence of two well-designed ongoing natural history studies in the USA/Australia and Europe created an environment in which the experts in the field were easily identified, and had participated in many parallel discussions about data collection within their groups (31–32). This created a collaborative environment in which potential issues of data collection had been considered in advance of the present project and in which many of the practical aspects of CDE creation had already been addressed. Consequently, issues tended to be readily resolved in development of the present CDEs. In addition, many of the CRFs used in the present project were directly derived from the natural history projects, allowing the process to move forward expeditiously. However, the CDE development process in FRDA was complicated by the need to include domains well outside of neurology, such as cardiology. Still, the European and Australia/USA natural history studies had considered these issues before the process, allowing expert cardiologists to be identified and introduced to the program without difficulty.

Having completed the present CDEs, their value can be established prospectively in several ways. First is the adaptation of study data collection to match that detailed in the CDEs. The European natural history has already incorporated some of the specific CDEs into its collection process. The US/Australian study, having a more established database, already matches most of the CDEs and their CRFs in data collection, but also will be slower to change based on the practical issues in database modification. This is a recognized issue in the establishment of centralized CDEs. A second possible way to monitor the utility of CDEs is in the recruitment of new individuals to the field and in particular the speed at which studies by new investigators are started. This may be hard to assess in FRDA, since the scale of the research is modest, and its ability to expand is limited compared to more common disorders. A final way is to assess the number of collaborative studies, particularly meta-analysis and biomarker studies that evolve from the CDE collections. Such studies may be crucial to FRDA, given the limited resources for study of rare disease. The collaborations developed through the CDE project have already been implemented in ongoing modifier gene studies of FRDA.

There are several limitations to the present proposed CDEs. Most important is that the CDEs are research tools. Thus, at present the recommendations include a core recommendation to use one of the three validated ataxia scales, chosen on an individual basis considering the exact research question of specific studies. Over time, the exact data elements (such as specific scales) that are most useful in understanding both short and long term change in FRDA will be identified, allowing streamlining of such recommendations as well as introduction of new elements. The present version, designated version 1.0, of the FRDA CDE elements will undergo annual reviews and periodic updates. The NINDS recognizes that the best way to ensure the FA CDEs are useful and the project accomplishes its goals is to periodically refine the CDEs based upon the feedback of researchers who have used them in their clinical studies.

Table 2.

Ataxia and Performance Measure Instrument Recommendations

| Name of Instrument | Classification |

|---|---|

| Friedreich Ataxia Rating Scale (FARS) | Core |

| International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale (ICARS) | Core |

| Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA) | Core |

| Low Contrast Letter Acuity | Core |

| Timed 25-Foot Walk | Core |

| 9-Hole Pegboard | Core |

| Assessment of Intelligibility of Dysarthric Speech (AIDS) | Supplemental |

| Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination – Third Edition (BDAE-3) | Supplemental |

| Friedreich’s Ataxia Impact Scale (FAIS) | Supplemental |

| Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS) OR Modified Fatigue Impact Scale - 5 Item Version (MFIS-5) |

Supplemental |

| PaTa test | Supplemental |

| Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (Peds QL) | Supplemental |

| SF-10 Health Survey for Children | Supplemental |

| SF-36 | Supplemental |

| Aerobic Cardiac Output | Exploratory |

| Bladder Control Scale (BLCS) | Exploratory |

| Bowel Control Scale (BWCS) | Exploratory |

| Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) | Exploratory |

| Functional Independence Measure (FIM) | Exploratory |

| Impact of Visual Impairment Scale (IVIS) | Exploratory |

| Jebsen-Taylor Hand Function Test | Exploratory |

| Modified Barthel Index | Exploratory |

| MOS Pain Effects Scale (PES) | Exploratory |

| Phonemic Verbal Fluency | Exploratory |

| Speech (Acoustic Analysis) | Exploratory |

| Stride Analysis and Gait Variability | Exploratory |

| Tardieu Scale | Exploratory |

Acknowledgments

The Common Data Element Project is funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health (contract No. N01-NS-7-2372).

Authors’ Roles

Research Project: As Friedreich’s Ataxia Common Data Element Working Group members, all authors contributed to the conception, organization and execution of the recommendations and paper.

Statistical Analysis: None

Manuscript Preparation: Drs. David Lynch and Massimo Pandolfo, serving as the Working Group Chairs, wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All others reviewed and critiqued it.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures

David R. Lynch has received grant support from the NIH, MDA, FARA, Penwest, Santhera, and Edison Pharmaceuticals. He is an unpaid consultant to Apopharma and Athena Diagnostics.

Martin B. Delatycki is a consultant to Healthscope Pathology.

Paul Kantor serves on an Advisory Board to Servier, for which his institution (but not himself) is compensated a pro-rata amount.

Jörg B. Schulz has made expert testimonies for Santhera and has served on advisory boards for Teva, Lundbeck, Merz and Santhera. He has received speaker honoraria by Merz, Pfizer, GSK, and Santhera, and research grants from the BMBF and the EU.

Robert Shaddy has acted as visiting professor at Saint Peter’s University Hospital and at Children’s Hospital Colorado; speaker/lecturer at Optum Health and the American Society of Transplantation; expert medical witness for Broadline Risk Retention; consultant/contractor for Wolters Kouwer Health Publishers; and has provided expert witness/medical-legal work for Sites and Harbison, Hancock, Daniel, Johnson and Nagle, PC, and The Doctors Company.

The following manuscript authors report no disclosures: Massimo Pandolfo, Susan Perlman, R. Mark Payne, Kenneth H. Fischbeck, Jennifer Farmer, Subha V. Raman, Lisa Hunegs, Joanne Odenkirchen, Kristy Miller, and Petra Kaufmann.

References

- 1.Harding AE. Friedreich's ataxia: a clinical and genetic study of 90 families with an analysis of early diagnostic criteria and intrafamilial clustering of clinical features. Brain. 1981;104:589–620. doi: 10.1093/brain/104.3.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lynch DR, Farmer JM, Balcer LJ, Wilson RB. Friedreich ataxia: effects of genetic understanding on clinical evaluation and therapy. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:743–747. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.5.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fantus IG, Seni MH, Andermann E. Evidence for abnormal regulation of insulin receptors in Friedreich's ataxia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76:60–63. doi: 10.1210/jcem.76.1.8421104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finocchiaro G, Baio G, Micossi P, Pozza G, di Donato S. Glucose Metabolism alterations in Freidreich's Ataxia. Neurology. 1988;38:1292–1296. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.8.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan RJ, Andermann E, Fantus IG. Glucose intolerance in Friedreich's ataxia: association with insulin resistance and decreased insulin binding. Metabolism. 1986;35:1017–1023. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(86)90037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coppola G, Coppola G, Marmolino D, et al. Functional genomic analysis of frataxin deficiency reveals tissue-specific alterations and identifies the PPARgamma pathway as a therapeutic target in Friedreich's ataxia. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:2452–2461. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herman D, Jenssen K, Burnett R, Soragni E, Perlman SL, Gottesfeld JM. Histone deacetylase inhibitors reverse gene silencing in Friedreich's ataxia. Nature Chemical Biology. 2006;2:551–558. doi: 10.1038/nchembio815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Babcock M, de Silva D, Oaks R, et al. Regulation of mitochondrial iron accumulation by Yfh1p, a putative homolog of frataxin. Science. 1997;276:1709–1712. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5319.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rotig A, et al. Aconitase and mitochondrial iron-sulphur protein deficiency in Friedreich ataxia. Nat Genet. 1997;17:215–217. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armstrong JS, Khdour O, Hecht SM. Does oxidative stress contribute to the pathology of Friedreich's ataxia? A radical question. The FASEB journal. 2010;24:2152–2163. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-143222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herman D, Jenssen K, Burnett R, Soragni E, Perlman SL, Gottesfeld JM. Histone deacetylase inhibitors reverse gene silencing in Friedreich's ataxia. Nat Chem Biol. 2006 Oct;2(10):551–558. doi: 10.1038/nchembio815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boesch S, Sturm B, Hering S, Goldenberg H, Poewe W, Scheiber-Mojdehkar B. Friedreich' sataxia: clinical pilot trial with recombinant human erythropoietin. Ann Neurol. 2007 Nov;62(5):521–524. doi: 10.1002/ana.21177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lynch DR, Perlman SL, Meier T. A phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of idebenone in friedreich ataxia. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:941–947. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Prospero NA, Baker A, Jeffries N, Fischbeck KH. Neurological effects of high-dose idebenone in patients with Friedreich's ataxia: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70220-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schulz JB, Di Prospero NA, Fischbeck K. Clinical experience with high-dose idebenone in Friedreich ataxia. J Neurol. 2009 Mar;256(Suppl 1):42–45. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-1008-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hawi A, Heald S, Sciascia T. Use of an adaptive study design in single ascending-dose pharmacokinetics of A0001 (a-tocopherolquinone) in healthy male subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2001 doi: 10.1177/0091270010390807. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boddaert N, Le Quan Sang KH, Rötig A, et al. Selective iron chelation in Friedreich ataxia: biologic and clinical implications. Blood. 2007 Jul 1;110(1):401–408. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-065433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marmolino D, Manto M, Acquaviva F, et al. PGC-1alpha down-regulation affects the antioxidant response in Friedreich's ataxia. PLoS One. 2010 Apr 7;5(4):e10025. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. [last accessed 12/17/11]; www.curefa.org/pipeline.html.

- 20.Tsou AY, Friedman LS, Wilson RB, Lynch DR. Pharmacotherapy for Friedreich ataxia. CNS Drugs. 2009;23(3):213–223. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200923030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adelson PD, Pineda J, Bell MJ, Abend NS, Berger RP, Giza CC, Hotz G, Wainwright MS. Common Data Elements for Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury: Recommendations from the Working Group on Demographics and Clinical Assessment. J Neurotrauma. 2011 doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.1952. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller AC, Odenkirchen J, Duhaime AC, Hicks R. Common Data Elements for Research on Traumatic Brain Injury-Pediatric Considerations. J Neurotrauma. 2011 doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.1932. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loring DW, Lowenstein DH, Barbaro NM, et al. Common data elements in epilepsy research: development and implementation of the NINDS epilepsy CDE project. Epilepsia. 2011 Jun;52(6):1186–1191. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03018.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maas AI, Harrison-Felix CL, Menon D, et al. Common data elements for traumatic brain injury: recommendations from the interagency working group on demographics and clinical assessment. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010 Nov;91(11):1641–1649. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.07.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedman LS, Farmer JM, Perlman S, et al. Measuring the rate of progression in Friedreich ataxia: implications for clinical trial design. Mov Disord. 2010;25:426–432. doi: 10.1002/mds.22912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lynch DR, Farmer JM, Tsou AY, et al. Measuring Friedreich ataxia: complementary features of examination and performance measures. Neurology. 2006;66:1711-6Fars. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000218155.46739.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bürk K, Mälzig U, Wolf S, et al. Comparison of three clinical rating scales in Friedreich ataxia (FRDA) Mov Disord. 2009 Sep 15;24(12):1779–1784. doi: 10.1002/mds.22660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cano SJ, Hobart JC, Hart PE, Korlipara LV, Schapira AH, Cooper JM. International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale (ICARS): appropriate for studies of Friedreich's ataxia? Mov Disord. 2005 Dec;20(12):1585–1591. doi: 10.1002/mds.20651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lynch DR, Farmer JM, Wilson RL, Balcer LJ. Performance measures in Friedreich ataxia: potential utility as clinical outcome tools. Mov Disord. 2005;20:777–782. doi: 10.1002/mds.20449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lynch DR, Farmer JM, Rochestie D, Balcer LJ. Contrast letter acuity as a measure of visual dysfunction in patients with Friedreich ataxia. J Neuroophthalmol. 2002;22:270–274. doi: 10.1097/00041327-200212000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. [last accessed 12/17/11]; www.curefa.org/network.html.

- 32. [last accessed 12/17/11]; www.e-facts.eu.

- 33.Rajagopalan B, Francis JM, Cooke F, et al. Analysis of the factors influencing the cardiac phenotype in Friedreich's ataxia. Mov Disord. 2010 May 15;25(7):846–852. doi: 10.1002/mds.22864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyer C, Schmid G, Görlitz S, et al. Cardiomyopathy in Friedreich's ataxia-assessment by cardiac MRI. Mov Disord. 2007 Aug 15;22(11):1615–1622. doi: 10.1002/mds.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson CL, Fahey MC, Corben LA, et al. Quality of life in Friedreich ataxia: what clinical, social and demographic factors are important? Eur J Neurol. 2007 Sep;14(9):1040–1047. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paulsen EK, Friedman LS, Myers LM, Lynch DR. Health-related quality of life in children with Friedreich ataxia. Pediatr Neurol. 2010 May;42(5):335–337. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Epstein E, Farmer JM, Tsou A, et al. Health related quality of life measures in Friedreich Ataxia. J Neurol Sci. 2008 Sep 15;272(1–2):123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.05.009. Epub 2008 Jun 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]