Abstract

Rationale

The ability of locomotor activity in a novel environment (Loco) and visual stimulus reinforcement (VSR) to predict acquisition of responding for cocaine and water reinforcers in the absence of explicit audiovisual signals was evaluated.

Methods

In Experiment 1, rats (n=60) were tested for VSR, followed by Loco, and finally acquisition of responding for cocaine (0.3 mg/kg/inf). In Experiment 2, rats (n=32) were tested for VSR, followed by Loco, and finally acquisition of responding for water (0.01 ml/reinforcer).

Results

There were three main findings. First, Loco and VSR were significantly associated (Exp 1: r = 0.49, p< 0.00; Exp2: r = 0.35, p< 0.05). Second, neither Loco (r = .00, p = 0.998) nor VSR (r = −0.12, p = 0.352) predicted acquisition of cocaine SA. Third, in the sub group of animals that acquired cocaine SA, VSR (r = 0.41, p< 0.01) but not Loco (r = 0.28, p = 0.10) was positively associated with operant responding for cocaine. Both Loco and VSR (Loco: r = 0.37, p< 0.04; VSR: r = 0.51, p< 0.00) were positively associated with operant responding for water reinforcers.

Conclusions

The results indicate that VSR is at least as good a predictor of cocaine reinforced responding as Loco. VSR was predictive of operant responding for both drug and water reinforcers, while Loco was found to be predictive of responding only for water reinforcers. In studies that present visual stimuli in association with drug delivery, Loco may be predicting acquisition of responding for VSR rather than drug.

Keywords: cocaine, drug abuse, self-administration, operant conditioning, rat, sensation seeking, novelty

Introduction

A widely used test of vulnerability to acquire drug self-administration (SA) is exploration of a novel environment. The amount of activity in the novel environment is referred to as locomotor response to novelty (Loco), and has been suggested to be an animal model of sensation seeking (SS; Dellu et al. 1993; Dellu et al. 1996; Olsen and Winder 2009). Animals with high locomotor activity, labeled high responders, SA more drug than low responder counterparts. High responders have greater SA across a wide range of different drugs, including amphetamine, and cocaine, when compared to low responders (Piazza et al. 1989; Piazza et al. 2000; Piazza et al. 1993a; Piazza et al. 1993b).

There is evidence that operant responding to produce sensory stimuli, such as light onset, may also predict drug SA. We have previously reported that high responder rats respond more to produce visual sensory reinforcers (VSRs) and that the same high responder rats respond more for reinforcing infusions of methamphetamine (METH; Gancarz et al. 2011b). Additionally, we have shown that Loco is positively associated with the reinforcing effectiveness of visual stimuli (VSi; Gancarz et al. 2012b). These data suggest that Loco and VSR may be mediated by similar underlying neural and behavioral processes. Based on these findings, we have speculated that sensory reinforcement may be an animal model of sensation seeking.

There is also evidence indicating the importance of visual cues in drug SA. For example, Deroche-Gamonet et al. (2002) demonstrated that the use of a visual stimulus enhanced acquisition of cocaine SA. Additionally, a series of experiments by Caggiula and colleagues (Caggiula et al. 2002a; Caggiula et al. 2009; Caggiula et al. 2001; 2002b; Chaudhri et al. 2007; Chaudhri et al. 2006; Donny et al. 1998; Donny et al. 2003; Palmatier et al. 2006)have shown that SA of nicotine is greatly enhanced by the presentation of a visual stimulus associated with nicotine. Taken together, (i) our data showing that Loco predicts the reinforcing effectiveness of visual stimuli, and (ii) the results showing that visual stimuli play an important role in drug SA, indicate that the intrinsic reinforcing effects of visual stimuli may be both an important predictor of drug SA, as well as an important determinant of the reinforcing effectiveness of drugs.

A potential limitation of Gancarz et al. (2011b) study was that a visual stimulus was used in both the light reinforcement study and methamphetamine SA testing phase, making it difficult to determine if rats were responding to produce the visual stimulus, methamphetamine or the combination in the SA phase. However, this confound is present in many studies of Loco as a predictor of drug SA, which often incorporate the use of a visual stimulus to signal drug delivery and/or associated time-out periods (Cain et al. 2008; Davis et al. 2008; Grimm and See 1997; Marinelli and White 2000). Based on our finding that Loco predicts light reinforcement (Gancarz et al. 2012b; Gancarz et al. 2011b), it is not entirely clear if Loco predicts drug SA or VSR in these studies. A goal of the present research is to compare the ability of both Loco and VSR to predict cocaine SA when audiovisual sensory cues are not associated with drug infusions.

Locomotor response to novelty and sensory reinforcement as predictors of responding for non-drug reinforcers

An important question is whether Loco and VSR specifically predict the responding for drug reinforcers or if they predict responding for reinforcers in general. There is some evidence that Loco predicts responding for both drug and non-drug reinforcers. Previous research has shown that high responders acquired responding for sucrose at a faster rate than low responders (Klebaur et al. 2001; Mitchell et al. 2005). Mitchell and colleagues suggested that high responders have accelerated learning of operant responses, rather than enhanced sensitivity to the reinforcing properties of the drug reinforcers. These authors reported that correlations between Loco and cocaine SA no longer existed if animals were pre-trained for sucrose reinforcement. They argued that if high responder rats had a generally greater sensitivity to the reinforcing effectiveness of drugs, then they should have responded more for drug, even after learning to respond for sucrose. The ability of VSR to predict responding for non-drug reinforcers has not been studied. A goal of the present research is to compare the ability of both Loco and VSR to predict operant responding for a water reward when audiovisual sensory cues are not associated with reinforcement.

The dose of cocaine used (0.3 mg/kg) for the SA study was chosen because it produces an acquisition rate of approximately 50% with the apparatus, and response requirements (including no visual stimulus) that were used in this study. This estimate of approximately 50% of the animals acquiring cocaine SA was obtained in a preliminary experiment that was part of the first author’s dissertation research (Gancarz 2011), which tested does of 0.1, 0.3, and 1.0 mg/kg/infusion cocaine. This preliminary study found that 3 of 10 rats acquired cocaine at the 0.1 dose, 7 of 10 rats acquired at the 0.3 dose and 9 of 10 rats acquired cocaine at the 1.0 mg/kg dose. The rationale for choosing a dose that produced approximately 50% acquisition rate was that SA performance produced by this dose would be sensitive to any predisposition for enhanced acquisition and even a possible predisposition toward a decrease in acquisition.

Exp 1: Association between Loco, VSR, and sensitivity to cocaine reinforcement

The goal of Experiment 1 was to determine if VSR and Loco differentially predict acquisition of a cocaine reinforcer.

Materials & Methods

Subjects

Sixty-one male Holtzman Sprague Dawley rats were used in Experiment 1. Subjects weighed approximately 250 g at the start of testing and were housed in pairs in plastic cages (42.5 × 22.5 × 19.25 cm). Rats were singly housed following surgery and for the duration of the SA phase of the experiment in order to protect the catheter/harness assembly. Lights were on in the colony room from 06:00 pm to 8:00 am. All behavioral testing occurred 7 days/week and was conducted during the dark phase of the light/dark cycle. Food (Harlan Teklad Laboratory Diet #8604, Harlan Inc., Indianapolis, IN) was continuously available. Access to water was restricted to 20 min following daily test sessions in all experiments. This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines set up by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The University at Buffalo, The State University of New York.

Apparatus

Locomotor Test Chambers

The locomotor chambers have been previously described (Gancarz et al. 2012b). Briefly, the locomotor activity was recorded by an infrared motion-sensor system (Hamilton-Kinder) fitted outside a standard plastic cage (42.5 × 22.5 × 19.25 cm). The activity-monitoring system monitors each of the beams at a frequency of 0.01s to determine whether the beams were interrupted. The interruption of any beam not interrupted during the previous sample was interpreted as an activity score.

Experimental Test Chambers

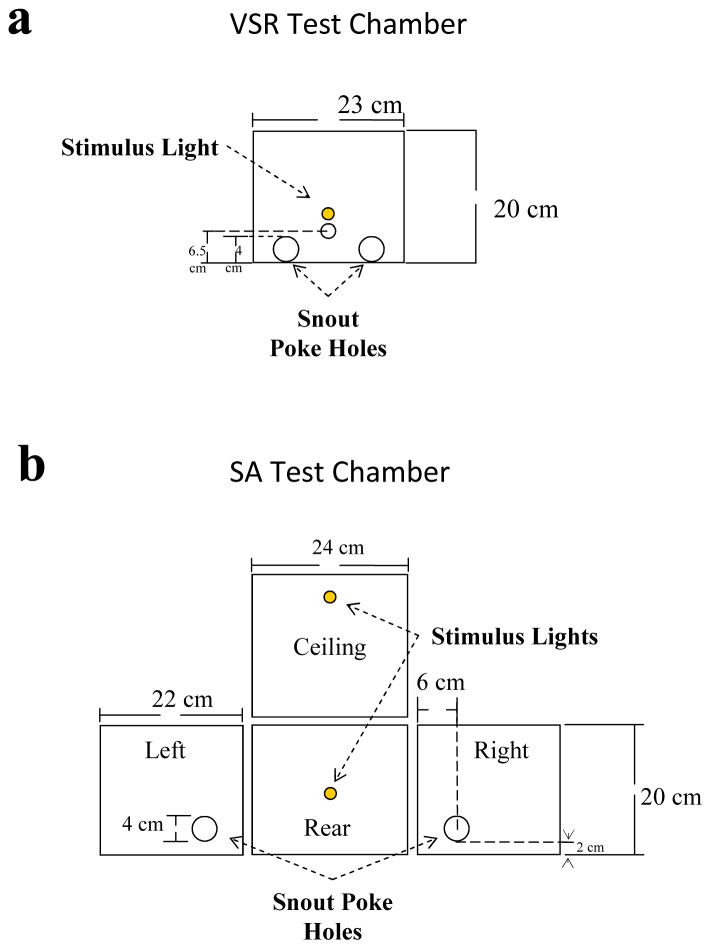

Twenty-four locally constructed test chambers were used, for VSR. Figure 1a provides a detailed description of the light reinforcement test chambers. The chambers had stainless-steel grid floors, aluminum front and back walls, Plexiglas sides, and a Plexiglas top. The test panel had two snout poke holes located on one wall of the test chamber. One stimulus light was mounted between the two snout poke holes, and a second stimulus light was mounted in the middle of the back wall of the test chamber.

Fig 1.

Illustration of the test panels used in visual stimulus reinforcement (a) and self-administration testing (b).

A separate set of twenty-four test chambers were used to test for cocaine and water SA. Figure 1b provides a detailed description of the SA test chambers. Three walls of the SA test chamber were aluminum, and one wall was Plexiglas. Snout poke holes were located on the left and right walls. Each SA chamber had stainless-steel grid floors, aluminum back and sidewalls, and a Plexiglas top and door. There were significant differences in the design of the VSR and SA chambers (see Fig. 1). VSR chambers have both the active and inactive snout poke holes located on a single wall of the experimental chamber while SA chambers had the snout poke holes located on opposite walls of the experiment chamber.

In both the VSR and SA test chambers, snout pokes and head entries were monitored with infrared detectors located 0.5 cm behind the test panel. All test chambers were housed in Coleman Coolers (Model # 3000000187) equipped with white noise fan generators, which attenuated sound and blocked external light sources and blocked perception of syringe infusion pumps (Model # PHM-100), which were located outside of the sound attenuated chamber. Both the VSR and SA test chambers were computer controlled through a MED Associates interface with MED-PC (version 4). The temporal resolution of the system is 0.01 seconds.

Drugs

-(−)Cocaine hydrochloride that was gifted by NIDA (RTI Log No: 13070-12C, ref # 013277), was dissolved in sterile saline and solutions (1.5 mg/ml) were made on a weekly basis. Cocaine was delivered via a syringe pump; pump duration was adjusted according to body weight in order to deliver the correct dose of drug (0.3 mg/kg/infusion cocaine).

Procedure

Phase 1: Visual stimulus reinforcement testing

Animals were placed in dark experimental chambers for a 10-day pre-exposure period. Daily sessions were 30 min in duration, during which snout pokes to either side was recorded but resulted in no programmed consequences. During pre-exposure, baseline levels of responding and side preferences for individual rats were determined. The information about preference was used to counterbalance the side assigned to be active during the VSR phase (see below). VSR testing immediately followed pre-exposure testing and consisted of six 30 min test sessions. The test chambers were dark during testing except when a response contingent visual stimulus was presented. The visual stimulus was the same as previously described in Gancarz et al., (2012b). Snout pokes into the active alternative resulted in illumination of the stimulus light for 5 s according to a variable interval 1 minute schedule of reinforcement. Snout pokes to the inactive alternative had no programmed consequences. The active snout poke hole was counterbalanced between the least and most preferred sides across all animals.

Phase 2: Locomotor activity in a novel environment

Subjects were placed into activity monitors for 60 min and locomotor activity was recorded. The dependent measure was locomotor counts operationally defined as the total number of horizontal and vertical beam breaks.

Phase 3: Cocaine self-administration

Following the locomotor test, rats were implanted with chronic indwelling jugular catheters. Implantation and maintenance of catheters have previously been described in Gancarz et al.,(2012a). Rats were allowed a 7-day recovery period following surgery. Patency tests were conducted as previously described in Gancarz et al., (2012a). Of the sixty-one rats tested, one animal pulled out the catheter/harness assembly following surgery and was not used for data analysis. All other animals were patent following the 10 days of SA testing. Therefore, data for sixty rats was reported.

One week after jugular catheter surgery, the rats were tested for acquisition of 0.3 mg/kg/infusion cocaine SA. Rats were connected to the experimental chamber as previously described (Gancarz et al., 2012a). Testing occurred during the animals’ dark cycle. Rats were tested for acquisition of cocaine SA for 10 test sessions. Responses to the active alternative resulted in IV injections of cocaine according to a Fixed Ratio 1 schedule of reinforcement. Each drug infusion was followed by a 30 s unsignaled time out period during which drug was unavailable. This time out period was implemented to prevent an accidental overdose. In this schedule, the first snout poke response into the active snout poke hole 30 s after the last cocaine infusion resulted in delivery of 0.3 mg/kg cocaine in the absence of any audiovisual cues. Snout poke responses to the inactive alternative resulted in no programmed consequences. Session duration was 60 min. Following testing, catheters were flushed and returned to the colony room.

Data Analysis

Dependent variables

The primary dependent measures for VSR were total responding (active + inactive responding) and the relative frequency of active responding (RFActive). The total responses measure indicates the increasing and/or possible decreasing effects of the light on responding (or activating effects of light onset). The RFActive, defined as: active responses/total responses indicates the proportion of snout pokes into the side that produced response contingent light onset. RFActive is a measure of preference for the response alternative that produced the visual stimulus, which indicates the guiding effects of light onset. For a more detailed discussion of the rationale for the use of total responses and RFActive as dependent measures for VSR, see Gancarz et al., (2011a; 2011b). The primary measure of Loco was locomotor counts. The primary dependent measures for SA was number of cocaine infusions.

Analysis

The criterion for acquisition of cocaine SA was an average of 10 infusions per day during the 10-session cocaine test phase. The correlation coefficients between: (i) Loco, pre-exposure, VSR and cocaine SA were determined using Pearson’s correlations tests. A two-tail alpha level used to identify significant association (p< 0.05). All dependent variables for the cocaine SA and water reinforcement were collapsed across all 10 days of acquisition testing for the correlation analysis. Dependent variables for VSR were averaged across the first 3 days of VSR testing. These correlations were first computed with all of the animals included and then separately for the animals the met the criterion for acquisition of cocaine SA.

Results

Association between Loco, VSR and SA in animals all animals tested for acquisition of cocaine SA (n=60)

Association between VSR and Loco

Table 1 shows a correlation matrix for the relationships between Loco, pre-exposure, VSR testing and cocaine infusions in the total sample of animals tested for acquisition of cocaine SA. There was no association between Loco and total snout poke responses emitted during the pre-exposure phase of VSR testing. However, there was a significant correlation between Loco and total responses emitted during VSR testing.

Table 1.

Correlational Matrix for all animals tested for acquisition of cocaine SA (n = 60)

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Loco | - | .02 | .49** | .08 | .00 |

| 2 Pre-exposure Total | - | .19 | −.12 | .21 | |

| 3 VSR Total | - | .34** | −.12 | ||

| 4 VSR RFActive | - | .07 | |||

| 5 Cocaine Infusions | - |

Note: Performance on VSR is averaged across Days 1–3 of testing.

Performance on 0.3mg/kg/inf cocaine SA is averaged across Days 1 – 10 of testing. Abbreviations: Loco = Locomotor activity in novel environment; Pre-exposure Total = total responses emitted during Days 1 &2 of the pre-exposure phase; VSR Total = total light reinforcement responses; VSR RFActive = Relative Frequency of light responses; Cocaine Infusions = Number of cocaine infusions earned.

p< 0.05,

p< 0.01

Association between VSR and cocaine SA

There was no significant association between any of the dependent measures of VSR (i.e., total pre-exposure responses, total VSR responses, RFActive light responses) and cocaine SA. Taken together, these data indicate neither Loco nor VSR is predictive of acquisition of 0.3 mg/kg/inf cocaine SA.

Association between Loco and cocaine SA

There was no association between Loco and number of cocaine infusions earned, indicating that Loco did not predict acquisition of cocaine SA.

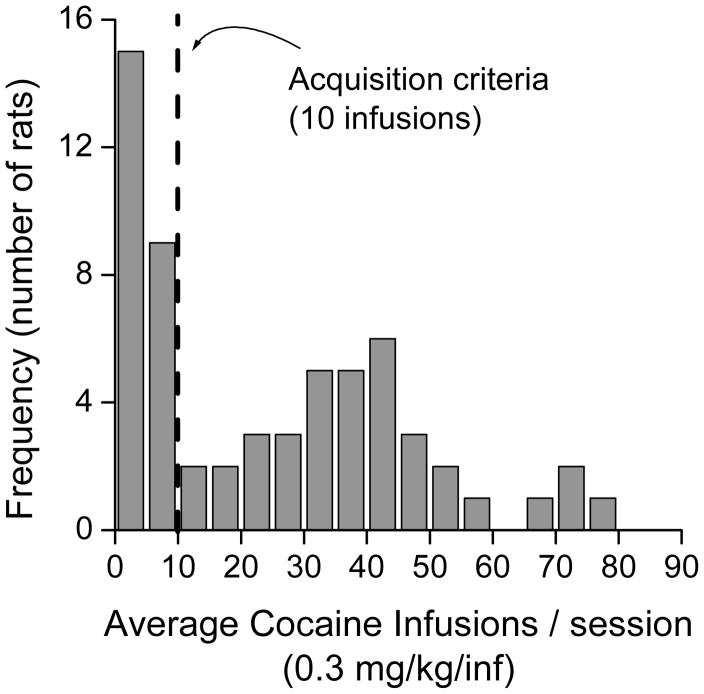

Cocaine SA

Of the 60 animals tested, thirty-six acquired (ACQ) cocaine SA and 24 failed to acquire (NON-ACQ) cocaine SA. Figure 2 shows the distribution of cocaine infusions in the total sample of animals tested. The dotted line indicates the criterion (average of 10 infusions across all days of testing) for acquisition of SA. There is a bimodal distribution in the number of cocaine infusions, with the first peak at less than 10 infusions per session, and the second peak at approximately 45 infusions per session. The median number of infusions per session was 3 infusions in NON-ACQ rats, and 38 infusions in ACQ rats.

Fig. 2.

This plot shows the distribution of cocaine infusions in the sixty animals tested for cocaine self-administration. The dotted line indicates the criterion used for acquisition. There was a bimodal distribution, with two distinct groups of rats.

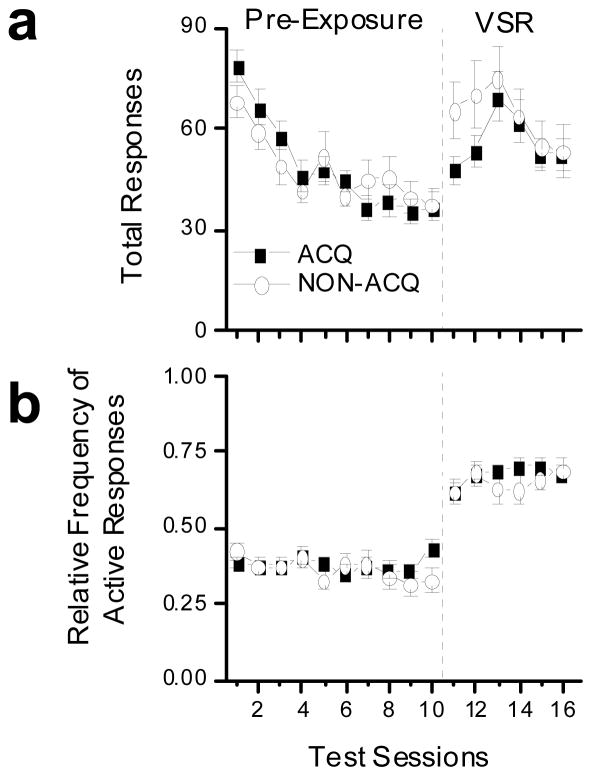

Visual stimulus reinforcement in ACQ and NON-ACQ rats

Responding for the ACQ and NON-ACQ animals during the pre-exposure and VSR phases of light reinforcement testing is shown in Figure 3. Figure 3a shows that responding decreased in both ACQ and NON-ACQ groups during the pre-exposure phase, and that responding increased during the VSR phase when light onset was made contingent upon responding. Figure 3b shows that introduction of the response contingent light increased the RFActive from less than 0.5 to approximately 0.7 in both the ACQ and NON-ACQ groups. There were no differences responding between the ACQ and NON-ACQ groups during either pre-exposure or VSR phases of testing (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

These plots show light reinforcement performance for all animals tested. The 10 sessions to the left of the dashed line were pre-exposure session during which responding had no effects. The 6 sessions to the right of the dashed line were visual stimulus reinforcement sessions where responses to the active alternative produced light onset according to a variable interval 1 minute schedule of reinforcement. The closed squares indicate the animals that met criterion for acquisition for cocaine self-administration (ACQ; n = 36), and the open circles indicate animals that failed to meet criterion for acquisition for cocaine self-administration (NON-ACQ; n = 24). Data are shown as group averages (± SEM). (a) The top panel shows total number of responses emitted during testing. (b) The bottom panel shows relative frequency of active responses. See text for detailed explanation.

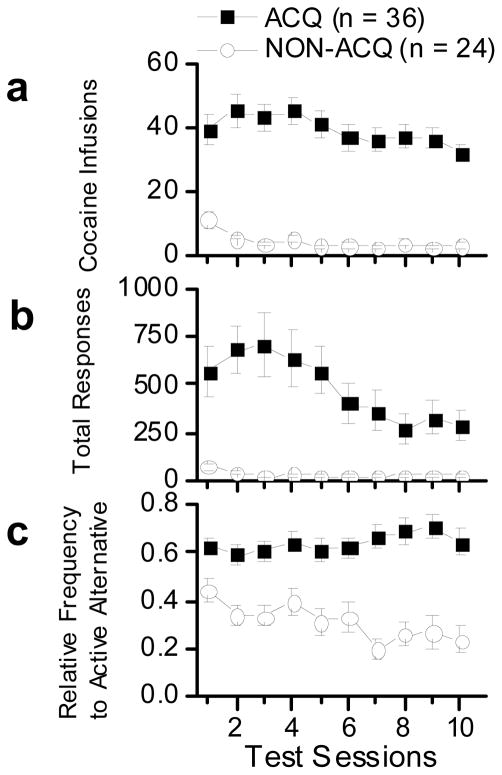

Cocaine SA in ACQ and NON-ACQ rats

Cocaine SA performance in ACQ and NON-ACQ animals is shown in Figure 4. There were clear differences in performance between the two groups. Animals in the ACQ group earned more cocaine infusions beginning with the first test session (Fig. 4a). Similarly, the ACQ group responded more throughout the 10-session test phase (Fig. 4b). Finally, the RFActive was consistently higher in the ACQ group than in the NON-ACQ group (Fig. 4c). Animals in the ACQ group had a preference for the active alternative that is significantly greater than would be expected by chance (0.64 ± 0.02, t(35) = 5.37, p 0.00). A further difference was that the RFActive responding remained stable across test sessions in the ACQ group, but had a decreasing trend across test sessions in the NON-ACQ group.

Fig. 4.

These plots show acquisition of cocaine SA for all animals tested. The closed squares indicate animals that met criterion for acquisition (ACQ; n = 36), and the open circles indicate animals that failed to meet criterion for acquisition (NON-ACQ; n = 24). Data are shown as group averages (± SEM). (a) The top panel shows number of cocaine infusions earned during 60 min test sessions. (b) The middle panel shows total number of responses emitted. (c) The bottom panel shows the relative frequency of active responses. See text for detailed explanation.

Association between Loco, VSR and SA in animals that acquired cocaine SA (n=36)

Loco predicts VSR

Table 2 shows associations between Loco, VSR, and cocaine SA with only the thirty-six ACQ animals included in the analysis.

Table 2.

Correlational Matrix for animals that acquired cocaine SA (n = 36)

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Loco | - | −.07 | .56** | .06 | .28 |

| 2 Pre-exposure Total | - | .03 | −.32 | −.01 | |

| 3 VSR Total | - | .14 | .41** | ||

| 4 VSR RFActive | - | .14 | |||

| 5 Cocaine Infusions | - |

Note: Performance on VSR is averaged across Days 1–3 of testing.

Performance on 0.3mg/kg/inf cocaine SA is averaged across Days 1 – 10 of testing. Abbreviations: Loco = Locomotor activity in novel environment; Pre-exposure Total = total responses emitted during Days 1 &2 of the pre-exposure phase; VSR Total = total light reinforcement responses; VSR RFActive = Relative Frequency of light responses; Cocaine Infusions = Number of cocaine infusions earned.

p< 0.05,

p< 0.01

Association between Loco and VSR

Loco was positively associated with total VSR responses but not with pre-exposure or the RFActive.

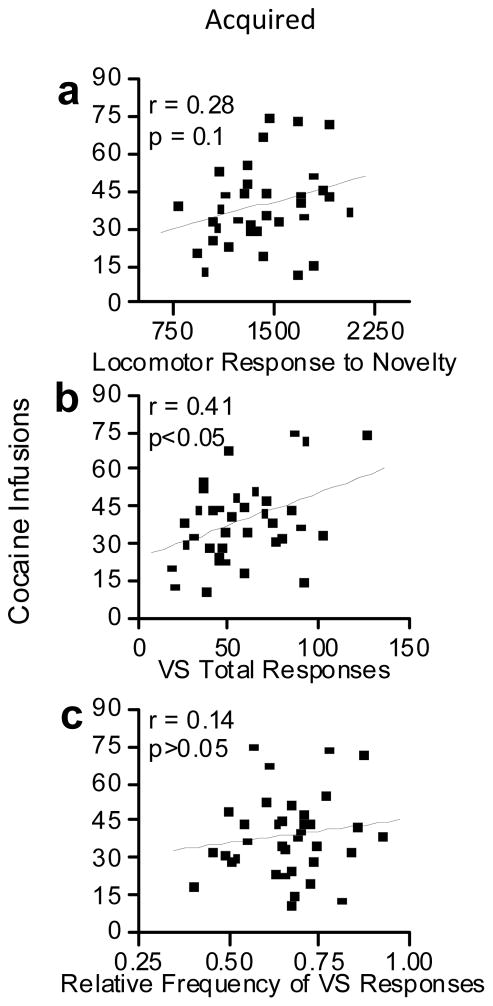

Association between Loco and cocaine SA

There was a non-significant positive association between Loco and cocaine infusions. [r = 0.28, p = 0.1, Fig. 5a].

Fig. 5.

These scatterplots show the relationships between cocaine self-administration and locomotor response to novelty, total visual stimulus reinforcement responses, and the relative frequency of active responses during visual stimulus reinforcement testing. (a) Shows a non-significant tendency for locomotor response to novelty to be associated with cocaine infusions. (b) Shows the positive association between total light reinforced responses and cocaine infusions. (c) Shows the lack of association between relative frequency of active light responses and cocaine infusions.

Association between VSR and cocaine SA

There was a significant positive association between total VSR responses and the number of cocaine infusions [r = 0.41, p< 0.05, Fig. 5b]. In contrast, the association between total responses emitted during the pre-exposure period and number of cocaine infusions was not significant. Interestingly, while total VSR responding was significantly associated with cocaine infusions, there was no association between RFActive light responses and cocaine infusions [r = −.01, p>0.05, Fig. 5c].

Exp 2: Association between locomotor response to novelty, VSR, and sensitivity to water reinforcement

The goal of Experiment 2 was to determine if VSR and Loco differentially predict acquisition of responding for a water reinforcer.

Materials & Methods

Subjects

Thirty-two male Holtzman Sprague Dawley rats were used in this experiment. Subjects were maintained as described in Experiment 1.

Apparatus

The apparati used to measure Loco, VSR, and water reinforcement were the same as those used in Experiment 1. The experimental chambers that were used to measure cocaine SA in Experiment 1 were used to measure water reinforcement in the current experiment.

Procedure

Timeline

The rats were tested for VSR (Phase 1) and Loco (Phase 2) as described in Experiment 1. Following VSR and Loco testing the rats were tested for acquisition of water reinforcement (Phase 3).

-

Phase 1

Visual stimulus reinforcement testing. As described for Experiment1.

-

Phase 2

Locomotor activity in a novel environment. As described in Experiment 1.

-

Phase 3

Water reinforcement. Rats were tested for acquisition of water reinforced responding for 10 days in a manner as similar as possible to the procedure used to test acquisition of cocaine reinforced responding in Experiment 1. Responses to the active alternative resulted in delivery of water according to a Fixed Interval 30 s schedule of reinforcement in the absence of any audiovisual cues. Snout poke responses to the inactive alternative resulted in no programmed consequences. Session durations were 60 minutes. Following testing, rats were returned to the colony room and allowed 20 min access to water in their home cage.

Data Analysis

Dependent variables

The primary dependent measures for VSR and Loco were the same as described for Experiment 1. The primary dependent measure for water reinforcement was number of water reinforcers.

Data analysis

The correlation coefficients between Loco, pre-exposure, VSR and water reinforcement were determined using Pearson’s correlations tests. A two-tail alpha level used to identify significant associations (p< 0.05).

Results

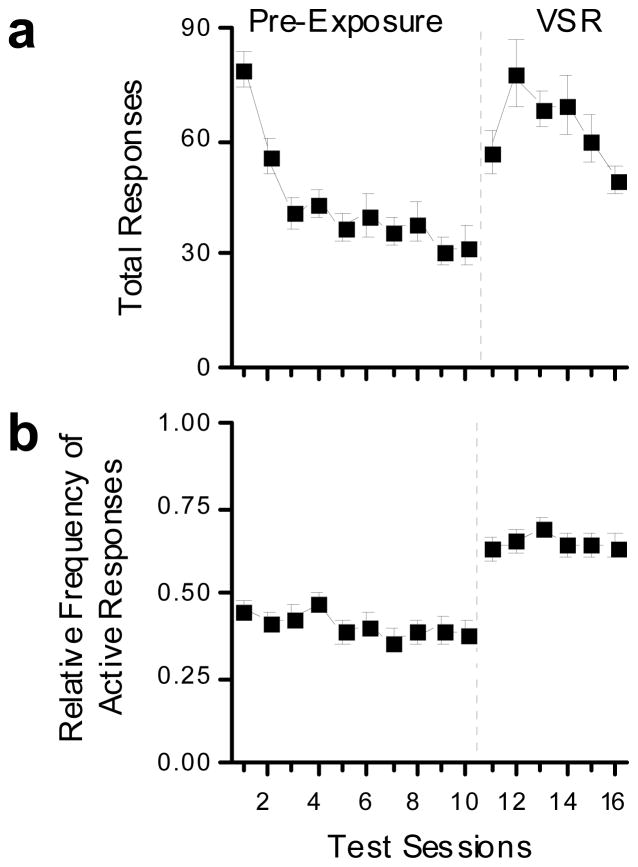

Visual stimulus reinforcement

The results of VSR testing in Experiment 2 were similar to the results of VSR testing described for the cocaine SA animals in Experiment 1 (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

These plots show light reinforcement performance for all water reinforcement animals tested. The 10 sessions to the left of the dashed line were pre-exposure sessions during which responding had no effects. The 6 sessions to the right of the dashed line were visual stimulus reinforcement sessions where responses to the active alternative produced light onset according to a VI 1 min schedule of reinforcement. Data are shown as group averages (± SEM). (a) The top panel shows total number of responses emitted during testing. (b) The bottom panel shows relative frequency of active responses. See text for detailed explanation.

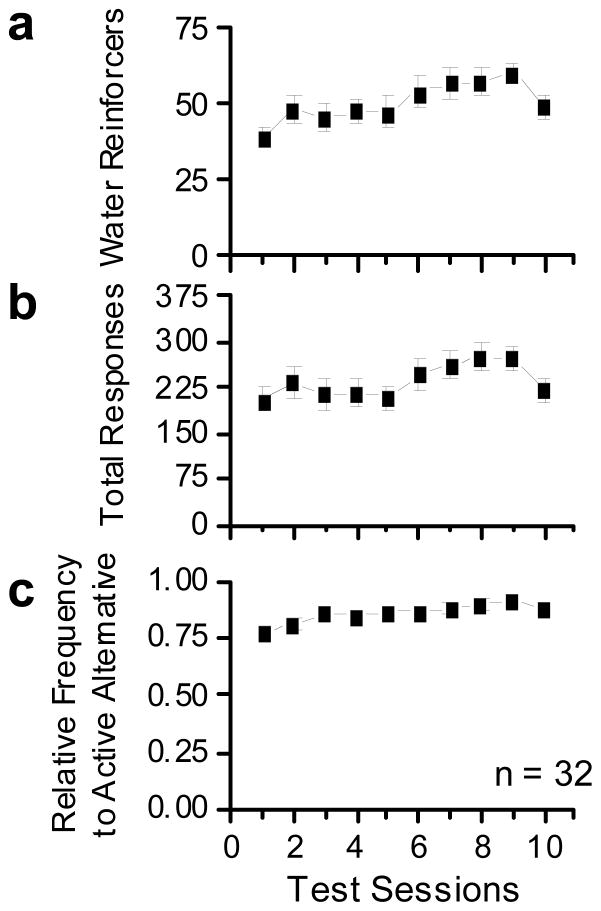

Sensitivity to water reinforcement

Water reinforcers

Figure 7 shows water self-administration across the 10 days of testing. Using the acquisition criterion of a minimum of 10 reinforcer presentations per secession to determine if animals acquired the reinforcement behavior, all 32 animals acquired water reinforcement. All animals responded for water reinforcers beginning with the first day of testing (Fig.7a). Total responding increased slightly with repeated testing (Fig.7b). The average RFActive was greater than 0.75 across all days of testing (Fig.7c).

Fig. 7.

These plots show water reinforcement performance for all rats tested. (a) The top panel shows number of water reinforcers earned across days of acquisition. (b) The middle panel shows total number of responses emitted across test days. (c) The bottom panel shows relative frequency of active responses to the water reinforced alternative. Data are shown as group averages (± SEM).

Association between Loco, VSR and water reinforcement

Association between Loco and VSR responses

There were significant correlations between Loco and the responses emitted during pre-exposure and responses emitted during VSR testing (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlational Matrix for all animals tested for acquisition of water reinforcement (n = 32)

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Loco | - | .55** | .35* | −.12 | .37* |

| 2 Pre-exposure Total | - | .26 | .06 | .24 | |

| 3 VSR Total | - | .17 | .51** | ||

| 4 VSR RFActive | - | .29 | |||

| 5 Water Reinforcers | - |

Note: Performance on VSR is averaged across Days 1–3 of testing. Performance on acquisition of 10 μl water reinforcement is averaged across Days 1 – 10 of testing. Abbreviations: Loco = Locomotor activity in novel environment; VSR Total = total light reinforcement responses; VSR RFActive = Relative Frequency of light responses; Water Reinforcers = Number of water reinforcers earned.

p< 0.05,

p< 0.01

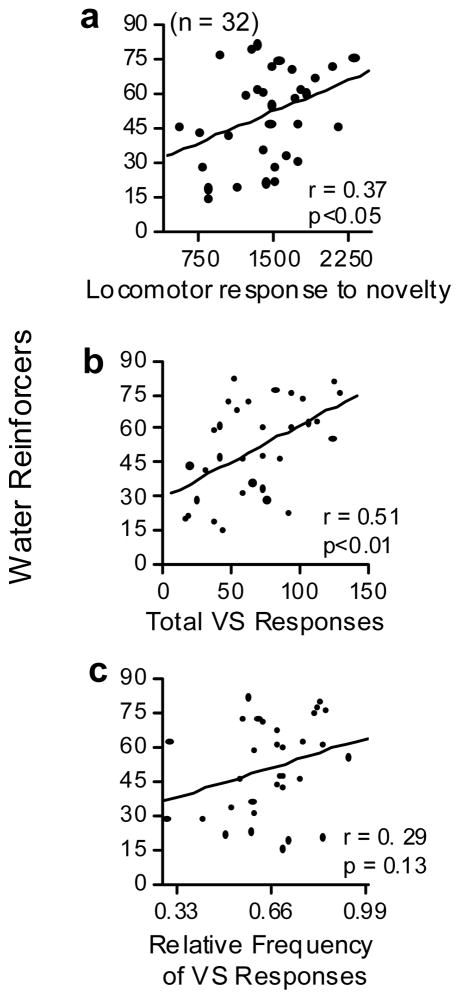

Association between Loco and water reinforcement

There was a significant association between Loco and number of water reinforcers earned (Fig. 8a).

Fig.8.

These scatterplots show the relationships between water reinforcement and locomotor response to novelty, total visual stimulus reinforcement responses, and the relative frequency of active visual stimulus reinforcement responses. (a) Shows a significant positive association between locomotor response and water reinforcement. (b) Shows a significant positive association between total visual stimulus reinforcement responses and water reinforcement. (c) Shows a non-significant positive association between relative frequency of active visual stimulus responses and water reinforcement.

Association between VSR and water reinforcement

There was a significant association between the number of VSR responses and the number of water reinforcers earned (Fig. 8b). There was a non-significant positive association between RFActive VSR responses and water reinforcement (Fig. 8c). Pre-exposure responding also produced a non-significant positive associated with the number of water reinforcers earned (Table 3, p = 0.13)

Discussion

The current experiments indicate that Loco and VSR are significantly associated. Since many SA studies present visual stimuli in association with drug delivery, the fact that Loco and VSR are associated raises the possibility that some of the significant associations previously reported between Loco and SA may, in fact, be due to an association between Loco and VSR, rather than Loco and acquisition of drug SA.

A clear result of the present study, in which drug infusions were not signaled, was that neither Loco nor VSR predicted which animals would acquire drug SA. However, when only the subgroup of animals that acquired drug SA was considered, VSR (r = 0.41, p< 0.01), but not Loco (r = 0.28, p = 0.10), was significantly associated with the number of cocaine infusions earned. This result, in contrast to the acquisition results, provides some evidence that in this selected group of rats, the reinforcing effects of cocaine were associated with reaction to novelty as measured by VSR but not Loco.

In addition, it was found that both Loco (r = 0.37, p< 0.04) and VSR (r = 0.51, p< 0.00) were positively associated with the number water reinforcers earned. Since all 32 rats in the water experiment acquired responding, it was not possible to determine if Loco or VSR differentially predicted acquisition of water reinforced responding. However, as was the case for cocaine SA, these results indicate that the reinforcing effects of water were associated with reaction to novelty as measured by Loco and VSR.

No Association between Loco nor VSR with acquisition of cocaine SA

The finding that neither Loco nor VSR predicted cocaine SA was surprising, as we have previously reported that Loco predicts acquisition of methamphetamine SA (Gancarz et al. 2011b), and there is a large literature showing Loco predicts acquisition of SA across a range of drugs (Deroche et al. 1993; Piazza et al. 1989; Piazza et al. 2000; Piazza et al. 1993b) including cocaine (Marinelli and White 2000).

Experiments studying the relationship between Loco and SA have most commonly used an extreme group approach, assigning animals to groups based on a median split of Loco performance. However, in those cases where correlations are reported, the correlation coefficients for the relationship between Loco and SA are often higher than those observed in the current experiment, ranging between r = 0.62 & 0.85. An important difference between the current experiment and many of the previously reported experiments, as well as our own previous experiment (Gancarz et al. 2011b), is that in the current experiment cocaine was delivered in the absence of any other experimentally controlled cues. Most experiments investigating the relationship between Loco and drug SA have incorporated the use of a VS to signal drug delivery (Cain et al. 2008; Davis et al. 2008; Grimm and See 1997; Marinelli and White 2000). The use of a visual stimulus in these studies may account for the different results between these studies and the current experiment.

In the current experiment and previous experiments (Gancarz et al. 2012b; Gancarz et al. 2011b), we have consistently found that high Loco rats respond more for a VSR. In a previous experiment (Gancarz et al. 2011b), we tested rats for acquisition of methamphetamine SA paired with a visual stimulus after VSR testing and found that high responder rats had higher rates of responding during SA testing than low responder rats. However, we could not determine if the animals were responding for the visual stimulus, methamphetamine, or some combination of the two. The present results, indicating that Loco fails to predict acquisition of cocaine SA when visual stimuli are not associated with drug delivery, are consistent with the interpretation that Loco predicted acquisition of responding for VS rather than drug reinforcement. The use of visual stimuli during drug SA may produce an unanticipated confound.

However, the use of visual stimulus to signal drug delivery may not account for all reports of a relationship between Loco and SA because some studies do not explicitly state if a stimulus was used to signal drug delivery (or time out following drug delivery; Piazza et al. 1989; Piazza et al. 1990; Piazza et al. 2000). If in fact there was no visual stimuli used in these studies, it is possible that there was an auditory cue associated with drug delivery as it is unclear from the description of these studies if the test chambers were in sound attenuating enclosures that would have prevented the sound of the infusion pump from acting as a cue for drug delivery.

One explanation for the result indicating that Loco and VSR did not predict acquisition of cocaine SA, but did predict the number of cocaine infusions earned in the subgroup of animals that acquired cocaine SA, is that the visual stimulus may have an important role in mediating the “initial” reinforcing effectiveness of cocaine. There is evidence that using a visual stimulus to signal cocaine infusions increases the rate of acquisition of SA. Deroche-Gamonet et al. (2002) trained rats to SA cocaine with and without a visual stimulus to signal cocaine infusions (1.0 mg/kg/infusion). Rats with cocaine infusions signaled by a visual stimulus acquired cocaine faster than rats that did not have a visual stimulus. There are several potential explanations of how visual stimuli may affect the “initial” reinforcing effectiveness of cocaine.

First, it seems likely that the first response contingent infusion of cocaine would be surprising and salient, but it is not clear that that the sensory effects of cocaine infusions would be as immediate as response contingent onset of a visual stimulus. The lack of immediacy may make it difficult for the rat to determine the response that produced the cocaine infusion. The immediate onset of a visual stimulus preceding the (presumably) more delayed effects of cocaine may help to “bridge the gap” between response and the effects of cocaine. According to this explanation, the visual stimulus may act as a learning aid that helped the rat associate the operant response with the sensory effects of the cocaine infusion. This explanation suggests that any non-aversive salient stimulus (such as the sound of the infusion pump) that predicts the drug infusions would increase acquisition of cocaine SA.

Second, there is evidence that cocaine has both rewarding and aversive effects (Riley 2011; Twining et al. 2009). Ettenburg and Geist (1991) trained rats to run a straight ally for a cocaine infusion in a goal box. They found that the rats would approach the goal box but then retreat a number of times before finally entering the goal box. These authors interpreted this approach and withdrawal pattern as indicating that cocaine and both rewarding and anxiogenic affects. An important factor in determining the relative aversiveness of cocaine appears to be the predictability of its delivery. Twining and colleagues (2009) reported that yoked rats, which receive unpredictable, uncontrollable cocaine infusions (0.33 mg/kg/infusion), developed a stronger condition taste aversions when taste was followed by cocaine. These authors also showed that rats with a history of yoked cocaine exposure had lower progressive ratio breakpoints for cocaine reinforcers compared to rats that had a history of response contingent cocaine SA.

There is a large literature indicating that animals prefer predictable punishers to unpredictable punishers (Abbott and Badia 1979; Badia et al. 1976). Additionally, unpredictable aversive events have been shown to produce greater behavioral disruption and arousal-based physiological disturbance relative to otherwise similar predictable aversive events (Estes and Skinner 1942; Seligman 1968; Seligman and Meyer 1970; Weiss 1970; Weiss et al. 1968). When applied to the potentially aversive effects of cocaine, it may be that visual stimuli that signal cocaine infusions decrease the aversive effects of cocaine by making them predictable. This explanation suggests that by providing a warning signal, the VS selectively decreases the aversive effects of cocaine infusions allowing the rewarding effects of cocaine to predominate.

A third possibility is that the reinforcing properties of the visual stimulus sustain initial responding long enough for the animals to be exposed to the reinforcing effects of the cocaine. Caggiula and colleagues (Caggiula et al. 2002a; Caggiula et al. 2009; Caggiula et al. 2001; 2002b; Chaudhri et al. 2007; Chaudhri et al. 2006; Donny et al. 1998; Donny et al. 2003; Palmatier et al. 2006) have shown that SA of nicotine is enhanced by the presentation of a VSR in association with nicotine. Of the three explanations, only this third possibility requires the visual stimulus to have primary reinforcing effects. To summarize, a visual stimulus that signals cocaine delivery may play an important role in determining the “initial” effects of cocaine infusions by “bridging the gap” between the response and delayed onset of cocaine making the occurrence of the sensory effects of cocaine predictable and perhaps less aversive. Alternatively (or in addition), the visual stimulus may also have primary reinforcing properties that encourage further responding. In the case of cocaine, the effects of the visual stimulus on acquisition may occur only during the “initial” learning of the response that produced cocaine. Once the response is learned, the cocaine infusions would be predictable and the visual stimulus no longer necessary.

Hypothesizing a role for the visual stimulus in mediating the “initial” reinforcing effectiveness of the cocaine suggests an explanation for the failure of Loco or VSR to predict acquisition of cocaine SA while at the same time being positively associated with cocaine SA in the subgroup of animals that acquired SA. The absence of a predictive stimulus for cocaine infusions may have disrupted acquisition of responding equivalently in both high responder and low responder rats.

Association with water reinforcement

The findings that both Loco and VSR were positively associated with cocaine SA in the subgroup of animals that acquired cocaine SA, in conjunction with the finding that Loco and VSR were also positively associated with responding for water reinforcers, indicates that reactivity to novel stimuli may be generally predictive of operant responding for reinforcers. The finding that Loco and VSR predicted responding for non-drug reinforcers is in agreement with other studies (Klebaur et al. 2001; Mitchell et al. 2005).

Mitchell and colleagues (2005) tested rats for acquisition of cocaine SA (0.25 mg/kg/inf). One group of rats was pre-trained to lever press for sucrose pellets, and another group of animals had no pre-training. They found a positive association between Loco and acquisition of responding for both sucrose pellets and cocaine in animals that were not pre-trained. An important feature of the Mitchell (2005) experiment is that the presentation of both cocaine and sucrose reinforcers was accompanied by 20s illumination of stimulus lights and withdrawal of the lever. It is plausible to suggest that light onset in addition to cocaine and sucrose pellets were reinforcers in the Mitchell experiment. Because the visual stimulus may have had reinforcing properties, it is not possible to say with certainty if the rats in the Mitchell experiment were responding to produce the visual stimulus, cocaine or the combination. It may be that, in the previously untrained rats, Loco predicted acquisition of responding for VSR rather than cocaine SA.

VSR as an animal model of sensation seeking

We have previously suggested the VSR may be an animal model of sensation seeking (Gancarz et al. 2012b). In the current study, VSR did not predict acquisition of cocaine SA. This result is in contrast to the human literature reporting high sensation seeking adolescents are more likely to initiate drug taking compared to low sensation seeking counterparts (Andrucci et al. 1989; Sutker et al. 1978). However, sensation seeking research predicting initiation of drug use is limited, and most sensation seeking experiments report results comparing drug-taking individuals to non-drug using controls. It is unclear from the results of these studies if previous drug history affects subsequent performance on sensation seeking scales. That is, sensation seeking may be altered by experience with drugs. A causal relationship cannot be determined from these studies.

At first consideration, the lack of specificity to drug SA does not seem to support the hypothesis that Loco and VSR may be animal models of sensation seeking. However, there is much evidence that drug and non-drug natural rewards share a common neural substrate (Olsen 2011), making it likely that drug and natural rewards have common predictors. There is evidence that humans identified as high sensation seeking may have elevated responding for both drug and non-drug rewards. For example, Bornovalova et al. (2009) have reported that operant responding for money reinforcers is elevated in humans identified as high sensation seeking.

A pre-clinical laboratory model of sensation seeking, would allow experiments to be performed that test causal relationships between the psychological construct of sensation seeking and drug consumption. For example, as was described above it is not clear from the human data if sensation seeking predisposes individuals to drug consumption or if drug consumption causes sensation seeking. This hypothesis could be tested in an animal experiment which reverses the order of testing of VSR and cocaine SA to determine if previous drug experience alters responding for a sensory reinforcer.

Conclusion

Experiment 1 examined the ability of Loco and VSR to predict acquisition of cocaine SA when the cocaine infusions were not signaled by audiovisual stimuli. Experiment 2 examined the ability of Loco and VSR to predict acquisition of responding for a water reinforcer. Neither VSR nor Loco predicated acquisition of cocaine SA. However, VSR, but not Loco, was positively associated with operant responding for cocaine (in the sub group of animals that acquired cocaine SA). Both VSR and Loco were positively associated with responding for water reinforcers. We speculate that the presence or absence of a visual stimulus or some other stimulus that signals cocaine infusions may play an important role in the acquisition of cocaine SA. These results indicate that it is important to understand the mediating effects of stimuli, particularly visual stimuli in drug SA experiments. An experiment, which directly compares the association between Loco and drug SA with (and without) visual stimuli, is needed to unambiguously determine if visual stimuli mediate the ability of Loco to predict drug SA. The results from the water reinforcement experiment indicate that Loco is generally predictive of operant responding for both drug and non-drug reinforcers. Data presented in this paper, and the results of other studies reviewed in this paper, indicate that Loco is positively associated with responding for visual stimuli, drug, and water reinforcers.

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of a doctoral degree at the State University of New York at Buffalo for Amy M. Gancarz. We would like to thank Linda Beyley for her assistance in conducting the experiments and Mark Kogutowski for his technical expertise in computer programming for the current experiments. We wish to thank Drs. Michael Bozarth, Micheal Dent, and Larry Hawk for their critical comments and editorial assistance on earlier versions of the manuscript. This work was partly supported by DA10588 to Jerry B. Richards and NIAAA training grant T32-AA007583-11. Amy M. Gancarz was supported by NIAAA training grant T32-AA007583-11 during the preparation of the manuscript. The cocaine tested in these experiments was gifted by NIDA. The authors on this manuscript reported no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Abbott B, Badia P. Choice for signaled over unsignaled shock as a function of signal length. J Exp Anal Behav. 1979;32:409–17. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1979.32-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrucci GL, Archer RP, Pancoast DL, Gordon RA. The relationship of MMPI and Sensation Seeking Scales to adolescent drug use. J Pers Assess. 1989;53:253–66. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5302_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badia P, Harsh J, Coker CC, Abbott B. Choice and the dependability of stimuli that predict shock and safety. J Exp Anal Behav. 1976;26:95–111. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1976.26-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, Cashman-Rolls A, O’Donnell JM, Ettinger K, Richards JB, deWit H, Lejuez CW. Risk taking differences on a behavioral task as a function of potential reward/loss magnitude and individual differences in impulsivity and sensation seeking. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;93:258–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiula AR, Donny EC, Chaudhri N, Perkins KA, Evans-Martin FF, Sved AF. Importance of nonpharmacological factors in nicotine self-administration. Physiol Behav. 2002a;77:683–7. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00918-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiula AR, Donny EC, Palmatier MI, Liu X, Chaudhri N, Sved AF. The role of nicotine in smoking: a dual-reinforcement model. Nebr Symp Motiv. 2009;55:91–109. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-78748-0_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiula AR, Donny EC, White AR, Chaudhri N, Booth S, Gharib MA, Hoffman A, Perkins KA, Sved AF. Cue dependency of nicotine self-administration and smoking. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;70:515–30. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00676-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiula AR, Donny EC, White AR, Chaudhri N, Booth S, Gharib MA, Hoffman A, Perkins KA, Sved AF. Environmental stimuli promote the acquisition of nicotine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002b;163:230–7. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1156-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain ME, Denehy ED, Bardo MT. Individual differences in amphetamine self-administration: the role of the central nucleus of the amygdala. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1149–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhri N, Caggiula AR, Donny EC, Booth S, Gharib M, Craven L, Palmatier MI, Liu X, Sved AF. Self-administered and noncontingent nicotine enhance reinforced operant responding in rats: impact of nicotine dose and reinforcement schedule. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;190:353–62. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0454-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhri N, Caggiula AR, Donny EC, Palmatier MI, Liu X, Sved AF. Complex interactions between nicotine and nonpharmacological stimuli reveal multiple roles for nicotine in reinforcement. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184:353–66. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis BA, Clinton SM, Akil H, Becker JB. The effects of novelty-seeking phenotypes and sex differences on acquisition of cocaine self-administration in selectively bred High-Responder and Low-Responder rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90:331–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellu F, Mayo W, Piazza PV, Le Moal M, Simon H. Individual differences in behavioral responses to novelty in rats. Possible relationship with the sensation-seeking trait in man. Personality Individual Differences. 1993;4:411–418. [Google Scholar]

- Dellu F, Piazza PV, Mayo W, Le Moal M, Simon H. Novelty-seeking in rats--biobehavioral characteristics and possible relationship with the sensation-seeking trait in man. Neuropsychobiology. 1996;34:136–45. doi: 10.1159/000119305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deroche-Gamonet V, Piat F, Le Moal M, Piazza PV. Influence of cue-conditioning on acquisition, maintenance and relapse of cocaine intravenous self-administration. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;15:1363–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.01974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deroche V, Piazza PV, Le Moal M, Simon H. Individual differences in the psychomotor effects of morphine are predicted by reactivity to novelty and influenced by corticosterone secretion. Brain Res. 1993;623:341–4. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91451-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donny EC, Caggiula AR, Mielke MM, Jacobs KS, Rose C, Sved AF. Acquisition of nicotine self-administration in rats: the effects of dose, feeding schedule, and drug contingency. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;136:83–90. doi: 10.1007/s002130050542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donny EC, Chaudhri N, Caggiula AR, Evans-Martin FF, Booth S, Gharib MA, Clements LA, Sved AF. Operant responding for a visual reinforcer in rats is enhanced by noncontingent nicotine: implications for nicotine self-administration and reinforcement. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;169:68–76. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1473-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes WK, Skinner BF. Some quantitative properties of anxiety. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1942;29:390–400. [Google Scholar]

- Ettenberg A, Geist TD. Animal model for investigating the anxiogenic effects of self-administered cocaine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1991;103:455–61. doi: 10.1007/BF02244244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gancarz AM. Doctoral dissertation. 2011. Sensory reinforcement as an animal model of sensation seeking: Strength of association to cocaine self-administration. Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. (Accession Order No. 3460752) [Google Scholar]

- Gancarz AM, Ashrafioun L, San George MA, Hausknecht KA, Hawk LW, Jr, Richards JB. Exploratory studies in sensory reinforcement: Effects of Methamphetamine. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2011a;20:16–27. doi: 10.1037/a0025701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gancarz AM, Kausch MA, Lloyd DR, Richards JB. Between-session progressive ratio performance in rats responding for cocaine and water reinforcers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012a doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2637-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gancarz AM, Robble MA, Kausch MA, Richards JB. Association between locomotor response to novelty and light reinforcement: Sensory reinforcement as an animal model of sensation seeking. Behavioural Brain Research. 2012b;230:380–388. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gancarz AM, San George MA, Ashrafioun L, Richards JB. Locomotor activity in a novel environment predicts both responding for a visual stimulus and self-administration of a low dose of methamphetamine in rats. Behav Processes. 2011b;86:295–304. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm JW, See RE. Cocaine self-administration in ovariectomized rats is predicted by response to novelty, attenuated by 17-beta estradiol, and associated with abnormal vaginal cytology. Physiol Behav. 1997;61:755–61. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(96)00532-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebaur JE, Bevins RA, Segar TM, Bardo MT. Individual differences in behavioral responses to novelty and amphetamine self-administration in male and female rats. Behav Pharmacol. 2001;12:267–75. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli M, White FJ. Enhanced vulnerability to cocaine self-administration is associated with elevated impulse activity of midbrain dopamine neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8876–85. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08876.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JM, Cunningham CL, Mark GP. Locomotor activity predicts acquisition of self-administration behavior but not cocaine intake. Behav Neurosci. 2005;119:464–72. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.2.464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen CM. Natural rewards, neuroplasticity, and non-drug addictions. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61:1109–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen CM, Winder DG. Operant sensation seeking engages similar neural substrates to operant drug seeking in C57 mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1685–94. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmatier MI, Evans-Martin FF, Hoffman A, Caggiula AR, Chaudhri N, Donny EC, Liu X, Booth S, Gharib M, Craven L, Sved AF. Dissociating the primary reinforcing and reinforcement-enhancing effects of nicotine using a rat self-administration paradigm with concurrently available drug and environmental reinforcers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;184:391–400. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0183-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Deminiere JM, Le Moal M, Simon H. Factors that predict individual vulnerability to amphetamine self-administration. Science. 1989;245:1511–3. doi: 10.1126/science.2781295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Deminiere JM, Maccari S, Mormede P, Le Moal M, Simon H. Individual reactivity to novelty predicts probability of amphetamine self-administration. Behav Pharmacol. 1990;1:339–345. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199000140-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Deroche-Gamonent V, Rouge-Pont F, Le Moal M. Vertical shifts in self-administration dose-response functions predict a drug-vulnerable phenotype predisposed to addiction. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4226–32. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04226.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Deroche V, Deminiere JM, Maccari S, Le Moal M, Simon H. Corticosterone in the range of stress-induced levels possesses reinforcing properties: implications for sensation-seeking behaviors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993a;90:11738–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Mittleman G, Deminiere JM, Le Moal M, Simon H. Relationship between schedule-induced polydipsia and amphetamine intravenous self-administration. Individual differences and role of experience. Behav Brain Res. 1993b;55:185–93. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(93)90114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley AL. The paradox of drug taking: The role of the aversive effects of drugs. Physiol Behav. 2011;103:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman ME. Chronic fear produced by unpredictable electric shock. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1968;66:402–11. doi: 10.1037/h0026355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman ME, Meyer B. Chronic fear and ulcers in rats as a function of the unpredictability of safety. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1970;73:202–7. doi: 10.1037/h0030219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutker PB, Archer RP, Allain AN. Drug abuse patterns, personality characteristics, and relationships with sex, race, and sensation seeking. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1978;46:1374–8. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.46.6.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twining RC, Bolan M, Grigson PS. Yoked delivery of cocaine is aversive and protects against the motivation for drug in rats. Behav Neurosci. 2009;123:913–25. doi: 10.1037/a0016498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JM. Somatic effects of predictable and unpredictable shock. Psychosom Med. 1970;32:397–408. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197007000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JM, Krieckhaus EE, Conte R. Effects of fear conditioning on subsequent avoidance behavior and movement. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1968;65:413–21. doi: 10.1037/h0025832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]