Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Although previous studies have revealed that preschool-aged children imitate both aggression and prosocial behaviors on screen, there have been few population-based studies designed to reduce aggression in preschool-aged children by modifying what they watch.

METHODS:

We devised a media diet intervention wherein parents were assisted in substituting high quality prosocial and educational programming for aggression-laden programming without trying to reduce total screen time. We conducted a randomized controlled trial of 565 parents of preschool-aged children ages 3 to 5 years recruited from community pediatric practices. Outcomes were derived from the Social Competence and Behavior Evaluation at 6 and 12 months.

RESULTS:

At 6 months, the overall mean Social Competence and Behavior Evaluation score was 2.11 points better (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.78–3.44) in the intervention group as compared with the controls, and similar effects were observed for the externalizing subscale (0.68 [95% CI: 0.06–1.30]) and the social competence subscale (1.04 [95% CI: 0.34–1.74]). The effect for the internalizing subscale was in a positive direction but was not statistically significant (0.42 [95% CI: −0.14 to 0.99]). Although the effect sizes did not noticeably decay at 12 months, the effect on the externalizing subscale was no longer statistically significant (P = .05). In a stratified analysis of the effect on the overall scores, low-income boys appeared to derive the greatest benefit (6.48 [95% CI: 1.60–11.37]).

CONCLUSIONS:

An intervention to reduce exposure to screen violence and increase exposure to prosocial programming can positively impact child behavior.

KEY WORDS: aggression, TV, preschool, prosocial, behavior

What’s Known on This Subject:

Children have been shown to imitate behaviors they see on screen.

What This Study Adds:

Modifying what children watch can improve their observed behavior.

Preschool-aged children in the United States spend an estimated 4.4 hours per day watching television at home and in day care settings.1 Although that amount alone might give one pause, equally, and perhaps more concerning, has been the amount of aggression that they watch.2,3 Decades of research rooted in observational theory have revealed that children emulate behaviors (good and bad) that they see on screen.4–8 Considerable research has established the adverse effects of violent television programming on children’s level of aggression.9–12 Cross-sectional and quasi-experimental studies of television viewing among school-age children and adolescents have revealed television viewing to be associated with aggression.13–15 Experimental designs have confirmed that reducing the amount of television children watch can reduce aggression among 9-year-olds.12,16 Considerably less attention has been given to the effects of television on preschool-aged children; however, longitudinal studies of television viewing before age 5 have revealed it to be a potential risk factor for the subsequent development of bullying and aggression measured in early elementary school.10,17–19 As aggressive behavior in the early childhood years has been repeatedly linked to violence in later youth and adolescence, interventions that might reduce early aggressive behavior could have significant societal implications.20–23

Research has also established that certain types of media programming can promote prosocial behavior.24–27 For example, high quality prosocial programs can improve racial attitudes, their social interactions, and their sharing propensities.28–31 This has led many researchers to emphasize that from a public health standpoint, content is as important as quantity in the ongoing debate about screen time. Unfortunately, the current viewing habits of most preschoolers, particularly those from disadvantaged families, lean heavily toward inappropriate programming (ie, noneducational or older child/adult focused) at the expense of higher quality shows.32–34 To date, no randomized controlled trial conducted in naturalistic environments with long-term follow-up has been conducted in preschool-aged children. We developed and tested an approach in which preschool-aged children’s viewing habits were altered such that they substituted high quality educational programs for violence-laden ones.

Methods

We conducted a randomized controlled trial of a “media diet” intervention. The treatment group received the media diet intervention described later, and the attention control group received a nutritional intervention designed to promote healthier eating habits. The study protocol was approved by the Seattle Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Subjects

Letters describing the studies were sent to families with age-eligible children (3–5 years) enrolled in community pediatric practices without regard to whether the child had been seen in the clinic recently. To be eligible, children needed to engage in some screen time each week and to have English-speaking parents. Families were given the opportunity to “opt out” of further recruitment efforts and also had the option to “opt in” by returning a postage-paid mailer. In a separate analysis, the differences between these 2 groups were found to be minimal.35 Those who neither opted out nor in were contacted by telephone and asked to participate. Attempts were made to oversample low-income families, as initially identified by Medicaid status or zip code of residence. At enrollment, parents were told only that “the study was being done to better understand how parents and children use television movies and computer games.” After enrollment, the survey and completed media diary were collected by study staff during a home visit at the start of the intervention. For all follow-up surveys, families had the option of returning materials by mail or submitting them online.

Intervention

The intervention framework was based on social cognitive theory36,37 and sought to increase parental outcome expectations and self-efficacy around making healthy media choices for their child, with a specific emphasis on replacing violent or age-inappropriate content with age-appropriate educational or prosocial content. The central premise informing much of the educational approach, consistent with observational theory, was that children imitate what they see on screen. Although the intervention addressed all screen time (television, DVDs/videos, computers, video games, handheld devices, etc), the primary focus was on television and videos because this accounts for the vast majority of screen time in preschool-aged children. No attempt was made to reduce total number of screen time hours; rather, the intervention focused on content and encouraging positive media behaviors such as coviewing. Intervention sessions began with the initial home visit, in which the families assigned to 1 of 3 case managers who collected assessment materials discussed the child’s current media use with the parent, shared intervention handouts that were specific to the family’s needs, and engaged the parent in goal setting. The home visit was then followed by mailings and follow-up telephone calls with the case manager for 12 months. The monthly mailings included a program guide tailored to the family’s available channels with recommended educational and prosocial television shows and schedules, and a newsletter with tips and reinforcement of key messages (sample newsletter available from corresponding author on request). The first 6 mailings also included DVDs with 5- to 10-minute clips of suggested educational and prosocial shows to pique children’s (and parents’) interest. Shows were selected for recommendation via program guides and DVDs utilizing ratings publicly available from Common Sense Media, with attempts made to include shows featuring diversity across gender, race, and ethnicity.

Duringthe monthly telephone calls, the case manager reviewed progress made on the parent’s goals since the last encounter, coached the parent through problem-solving around barriers as needed, and worked with the parent to set new goals as appropriate. The control group received a nutrition intervention, with analogous monthly newsletters promoting healthy food choices and monthly check in calls.

In summary, the importance of reducing exposure to violent television and replacing it as needed with educational/prosocial programming in the intervention group was emphasized at the initial visit, in the monthly newsletters, during the monthly telephone calls with the research assistant, by monthly program guides tailored to the participating families’ television service, and by providing examples of the types of programs that we deemed age appropriate and worthwhile. In addition, at the initial visit, parents were taught how to use the V chip on their television (if they wished) and how to set up kid zones on their DVR (where available). These practical strategies were also reinforced in newsletters.

Outcomes

Our primary outcomes were derived from the Social Competence and Behavior Evaluation (SCBE), parent version. The SCBE is a well-validated measure with both an overall score and subscales for internalizing (anxious, depressive, and withdrawn) and externalizing (angry, aggressive, oppositional) behaviors, as well as a subscale for social competence. Norms vary by age and gender.38 Higher scores indicate more positive behavior, for both the overall score and all subscales. We hypothesized that the intervention would increase the overall score and each of the 3 subscale scores. The SCBE was collected at each time point (baseline and 6 and 12 month follow-up). Based on our expected sample size, we estimated 80% power to detect differences of 1/4 of an SD in our primary outcomes.

Other Variables

Child and family demographic data were collected via a parent survey at baseline. Given the substantial number of multiracial children, race and ethnicity were coded as nonmutually exclusive variables from a “check all that apply” question, so proportions do not add up to 100%. Families are considered to be low income if their self-reported household income for the number of household members is below 200% of 2009 Federal Poverty Guidelines.

Child media use and content was assessed via media diaries at each time point. These diaries were modeled on ones used in the Panel Study of Income Dynamics Child Development Supplement.39 Parents were instructed to prospectively complete diaries by filling in time of day, name of show, platform (eg, television, DVD, etc), and who was watching with them (sample diary available from authors on request). At baseline, parents completed the media diaries prospectively for 1 week. For children who were in the care of other adults during the day (child care, relatives, etc), parents were asked to have those adults help complete the media diaries as well. Diaries captured time, content title, and co-use for television, video game, and computer use, and were subsequently coded for ratings, content, and pacing. The protocol for coding violence was based on that used for the Panel Study of Income Dynamics Child Development Supplement39 and categorized violence for each program by frequency (none, isolated, episodic, or central) and type (mild/slapstick, fantasy violence, sports violence, realistic, or gratuitous). Prosocial programming was defined as that which role modeled nonviolent conflict resolution, cooperative problem solving, empathy and recognition of emotions, manners, and helping others. Coding for prosocial programming was further broken down into categories of “primary” and “incidental,” just as was the case with educational programming. In the primary category, prosocial behaviors were an explicit theme of the program and were consistently role modeled; examples include Sesame Street, Dora the Explorer, and Super Why. In the incidental category, prosocial behaviors were role modeled, but inconsistently; examples include Curious George, Mickey Mouse Clubhouse, and Sid the Science Kid. For this article, we dichotomized prosocial content as present or not.

The first wave was coded by 2 researchers (Ms Liekweg and Dr Garrison) until 90% agreement was reached, with disagreements resolved through consensus. Subsequent diaries were coded by 1 researcher (Ms Liekweg), with a random 5% also coded by the second researcher to ensure 90% agreement was maintained.

At the study conclusion, parents in the intervention arm evaluated the program by responding to 2 questions: (1) would they recommend the program to other parents and (2) do they feel better about their child’s media use.

Analysis

Missing data for the questions contributing to the SCBE scales were imputed by using simple imputation with the Stata (Stata Corp, College Station, TX) impute command for subjects with no more than 20% of items missing in the scale. Each item used in the analysis had <2% of values missing. Descriptive and bivariate statistics were calculated, with t tests used to compare continuous variables between the intervention and control groups, and χ2 tests for categorical variables.

The main intervention effect was tested by using linear regression, with the SCBE overall, externalizing, internalizing, and social competence scores as the outcomes at both the 6- and 12-month time points. Each model controlled for the child’s baseline score for the domain analyzed and took into account case manager as a random effect. Standardized effect sizes were calculated by dividing the β coefficient for the intervention effect by the standardized deviation of the score (Cohen’s d). In a secondary analysis, we tested for effect modification by using the Wald test for interaction terms by gender and low-income status at the 6-month follow-up. All analyses were conducted by using Stata/SE, version 10.

Results

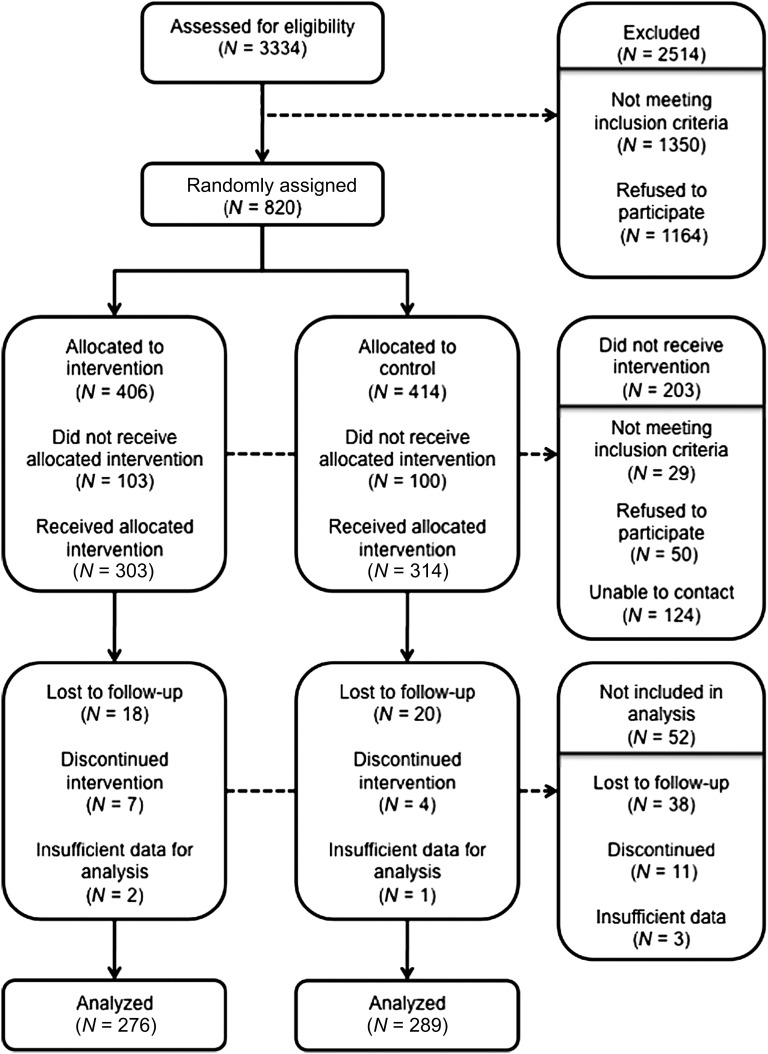

Of the 3334 families contacted and assessed for eligibility (Fig 1), 1350 (40%) did not meet inclusion criteria (742 did not watch at least 3 hours of television per week; 31 did not meet the age requirement; 453 did not meet the language requirement; and 124 did not live in Seattle), 35% declined to participate, and the remaining 25% (N = 820) were randomly assigned; of these, 617 (75%) completed the baseline visit. A total 565 (92%) of those completing the baseline survey completed at least 1 follow-up survey and had sufficient data to be analyzed, with 557 included in the 6-month analysis and 539 included in the 12-month analysis. The demographic characteristics of the included children and their families was representative of the Seattle area, and the only significant difference between study arms in baseline characteristics was a somewhat higher proportion of children in the control arm (43%) who had an older sibling at home, as compared with the intervention arm (34%).

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram.

Total screen time did not vary between groups at baseline or follow-up (Tables 1 and 2). Violence exposure did not differ between groups at baseline but was significantly less in the intervention compared with the control group both in terms of minutes and as a proportion of total daily screen time (Table 2). Although exposure to prosocial content was somewhat higher in the intervention group than in the control group at baseline (Table 2), posthoc regression analyses still revealed significantly increased prosocial exposure at the 6-month follow-up both in terms of minutes (P < .01) and as a proportion of total screen time (P = .02) after adjusting for baseline prosocial exposure. Between baseline and the 6-month follow-up, total daily screen time increased by 13.5 minutes in the control group and 16.2 minutes in the intervention group; however, this increase was accounted for by more violent minutes in the control group (increase of 6.8 vs 0.3 in the intervention arm) and by more prosocial minutes in the intervention group (9.9 vs 1.9). No significant differences were observed in the proportion of screen time reported as coviewing with an adult, which remained stable at 68% to 70% across all arms and time points, and may reflect social desirability bias in reporting.

TABLE 1.

Study Sample

| Intervention, N = 276 | Control, N = 289 | |

|---|---|---|

| Child demographics | ||

| Girl, % | 45 | 46 |

| Age in mo, mean(SD) | 50.9 (7.7) | 51.6 (7.7) |

| Race/ethnicity (not mutually exclusive), % | ||

| White | 82 | 81 |

| Black | 8 | 8 |

| Hispanic | 6 | 7 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 14 | 18 |

| Native American | 3 | 3 |

| Family demographics, % | ||

| Low-income | 18 | 13 |

| One adult household | 7 | 5 |

| Older sibling(s)a | 34 | 43 |

| Respondent is mother | 88 | 88 |

| Respondent education, % | ||

| High school or less | 19 | 18 |

| College degree | 45 | 44 |

| Graduate or professional degree | 36 | 38 |

| Child baseline media use | ||

| Television in bedroom, % | 8 | 8 |

| Average daily total use, min, mean(SD) | 73.9 (50.9) | 70.4 (48.5) |

| Average evening use, min, mean(SD) | 13.7 (16.1) | 13.7 (18.0) |

| Average daily violent content, min, mean(SD) | 22.1 (25.8) | 22.9 (31.0) |

P value is <0.05 for difference between groups.

TABLE 2.

Screen Time and SCBE Scores by Study Group

| Baseline | T6 | T12 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily total screen time, min | |||

| Control | 70.4 | 83.9 | 81.3 |

| Intervention | 73.9 | 90.1 | 78.2 |

| P | .41 | .25 | .53 |

| Daily screen time with central or episodic violence | |||

| Control | 22.9 | 29.7 | 26.8 |

| Intervention | 22.1 | 22.4 | 23.5 |

| P | .76 | .04* | .30 |

| Proportion of daily screen time with central or episodic violence | |||

| Control, % | 29.2 | 30.0 | 30.1 |

| Intervention, % | 28.1 | 22.9 | 25.2 |

| P | .63 | .01* | .09 |

| Daily screen time with prosocial content | |||

| Control | 28.9 | 30.8 | 28.3 |

| Intervention | 33.5 | 43.4 | 33.4 |

| P | .06 | <.001* | .12 |

| Proportion of daily screen time with prosocial content | |||

| Control, % | 42.4 | 40.0 | 37.7 |

| Intervention, % | 47.9 | 49.3 | 44.8 |

| P | .02* | <.01* | .03* |

| SCBE overall score | |||

| Control | 106.03 | 106.38 | 107.93 |

| Intervention | 105.96 | 108.36 | 109.57 |

| P | .94 | .047 | .10 |

*P < .05.

In the primary outcome analyses, the intervention resulted in significant improvements in the overall SCBE score at 6 months, as well as the externalizing and social competence subscales (Table 3). At 6 months, the overall mean SCBE score was 2.11 points better (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.78–3.44) in the intervention group as compared with the controls, and similar effects were observed for the externalizing subscale (0.68 [95% CI: 0.06–1.30]) and the social competence subscale (1.04 [95% CI: 0.34–1.74]). Both subscales demonstrated a trend toward improvement over time in each arm (Table 2), as might be expected with age during this developmental period, but with the regression results revealing greater improvement in the intervention arm (Table 3). Although the effect for the internalizing subscale was in a positive direction, it was not statistically significant (0.42 [95% CI: −0.14 to 0.99]). Although the effect sizes did not noticeably decay at 12 months, the effect on the externalizing subscale was no longer statistically significant (P = .05).

TABLE 3.

Regression Results From Primary Models

| Outcome | Effect Size | β* | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall SCBE score | ||||

| 6 mo (N = 557) | 0.19 | 2.11 | 0.78 to 3.44 | <.01 |

| 12 mo (N = 539) | 0.18 | 1.96 | 0.41 to 3.50 | .01 |

| Externalizing scale | ||||

| 6 mo (N = 557) | 0.14 | 0.68 | 0.06 to 1.30 | .03 |

| 12 mo (N = 539) | 0.14 | 0.67 | −0.02 to 1.36 | .05 |

| Internalizing scale | ||||

| 6 mo (N = 557) | 0.09 | 0.42 | −0.14 to 0.99 | .14 |

| 12 mo (N = 539) | 0.10 | 0.43 | −0.15 to 1.02 | .15 |

| Social competence scale | ||||

| 6 mo (N = 557) | 0.17 | 1.04 | 0.34 to 1.74 | <.01 |

| 12 mo (N = 539) | 0.14 | 0.82 | 0.02 to 1.62 | .04 |

β reflects the raw regression coefficient. Each model also controlled for the child’s baseline score.

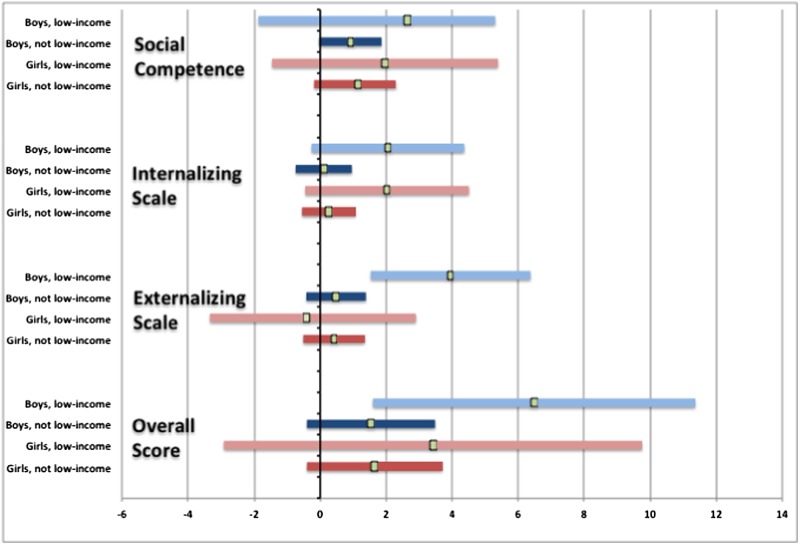

Although we detected no significant effect modification by gender or low-income status, there was a trend toward an increased effect of the intervention in low-income boys for both the overall SCBE score (P = .12) and the externalizing subscale (P = .11). In Fig 2, we present regression results after stratifying by gender and low-income status, where we see statistically significant effects for low-income boys on the overall score (6.48 [95% CI: 1.60–11.37]) and the externalizing subscale (3.95 [95% CI: 1.53–6.37]). For the internalizing subscale, we saw similar intervention effects across gender, but the intervention effect was statistically significant in low-income children (1.90 [95% CI: 0.23–3.56]) but not nonlow-income children (0.18 [95% CI: −0.41 to 0.77]).

FIGURE 2.

Regression results for SCBE scores at 6 months by gender and household income (β with 95% CI).

The intervention itself was well received. Overall, 77% of parents “would” recommend the program to other families, and 20% “might” recommend it. Thirty-four percent of parents felt much better about their child’s media use than they did at the study’s start, and 35% felt “a little better.”

Discussion

We demonstrated that an intervention to modify the viewing habits of preschool-aged children can significantly enhance their overall social and emotional competence and that low-income boys may derive the greatest benefit. By focusing on content rather than quantity, this study is the first to our knowledge to employ a harm reduction approach to mediating the untoward effects of television viewing on child behavior. Importantly, we did not see an increase in total viewing time in the intervention group compared with the control group. Both groups increased their viewing time, which likely reflects the fact that children watch more television as they age.

Although they varied by group and outcome, the overall effect sizes we achieved range from 0.09 to 0.19, which using Cohen’s scale could be interpreted as small. However, they are consistent with what has been achieved in the context of other interventional trials designed to improve children’s behavior.40 Furthermore, the effects in the particularly high-risk subgroup of low income boys are substantial. Future studies may identify and apply this approach to particularly vulnerable populations. Although we know that the roots of aggression in later years begin in early childhood, few studies to date have focused on preschool aggression prevention.41 Most prevention programs begin at school entry40 and preschool programs to date have largely focused on secondary prevention and treatment.42

This study has a number of limitations that warrant mention. First, as with all behavioral interventions, it was not possible to blind the parents to study arm. Although parents were not told the purpose of the study, they may have deduced it, and this may have biased the reported results. However, the active intervention period consisted of 6 months, and our analysis included data from as much as 1 year later. Further, in a previous article, we report that we also found improvement in children’s sleep in the intervention arm (a finding that is plausible based on previous studies revealing that violent content can cause sleep problems in children).43 Given that sleep was not a target of the intervention, these findings lend additional credibility to our behavioral outcomes. Finally, we did find a difference between study arms in violence exposure as measured by the coded media diaries. Parents completed these without knowledge of which shows we categorized as violent. Given that there was no difference in total screen time between groups, parents would have to have intentionally misrepresented the shows their children watched (rather than just omitting violent ones), which seems unlikely. Second, our sample may not be representative of other communities. However, our stratified analyses revealed effects regardless of income. Third, we focused only on media content in the home although we know that ∼40% of preschool-aged children spend time in out-of-home care arrangements where in many cases an additional 1 to 2 hours of television is viewed.1 Interventions targeting child care viewing practices should also be explored and may in fact enhance the effects achieved through focusing exclusively on home-based viewing. Finally, given that we succeeded in both increasing prosocial/educational content and reducing violent content, we cannot ascertain whether an increase in the former or a decrease in the latter was more important.

In spite of these limitations, our study has some important implications. Population-based aggression prevention approaches for preschool-aged children are generally lacking in part because of the challenge posed by deploying a far-reaching and broad-based approach outside of the structured environments of schools or day cares. This approach we undertook by using a widely accepted and highly used medium could therefore have broad public health impact, especially given the favorable ratings it received from participants. Although television is frequently implicated as a cause of many problems in children, our research indicates that it may also be part of the solution. Future research to perhaps further enhance media choices particularly for older children and potentially with an emphasis on low income boys is needed.

Glossary

- CI

confidence interval

- SCBE

Social Competence and Behavior Evaluation

Footnotes

This trial has been registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (identifier NCT01459835).

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Funded by a grant from the National Institute for Child Health and Development (to Dr Christakis). Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

COMPANION PAPERS: Companions to this article can be found on pages 439 and 589, and online at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2012-1582 and www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2012-3872.

References

- 1.Tandon PS, Zhou C, Lozano P, Christakis DA. Preschoolers’ total daily screen time at home and by type of child care. J Pediatr. 2011;158(2):297–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christakis DA, Zimmerman FJ. The Elephant in the Living Room: Make Television Work for Your Kids. Emmaus, PA: Rodale; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yokota F, Thompson KM. Violence in G-rated animated films. JAMA. 2000;283(20):2716–2720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bandura A. Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1977 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bandura A, Ross D, Ross SA. Imitation of film-mediated aggressive models. J Abnorm Soc Psychol. 1963;66(1):3–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bushman BJ, Huesmann LR. Short-term and long-term effects of violent media on aggression in children and adults. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(4):348–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson CA, Sakamoto A, Gentile DA, et al. Longitudinal effects of violent video games on aggression in Japan and the United States. Pediatrics 2008;122(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/122/5/e1067 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Anderson DR, Huston AC, Schmitt KL, Linebarger DL, Wright JC. Early childhood television viewing and adolescent behavior: the recontact study. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2001;66(1):I–VIII, 1–147 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christakis DA, Zimmerman FJ, DiGiuseppe DL, McCarty CA. Early television exposure and subsequent attentional problems in children. Pediatrics. 2004;113(4):708–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacBeth TM. Indirect effects of television: creativity, persistence, school achievement, and participation in other activities. In: MacBeth TM, ed. Tuning in to Young Viewers: Social Science Perspectives on Television. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1996:149–220 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson TN, Wilde ML, Navracruz LC, Haydel KF, Varady A. Effects of reducing children’s television and video game use on aggressive behavior: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(1):17–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bushman BJ, Anderson CA. Media violence and the American public: scientific facts versus media misinformation. Am Psychol. 2001;56(6-7):477–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bushman BJ, Cantor J. Media ratings for violence and sex: implications for policymakers and parents. Am Psychol. 2003;58(2):130–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paik H, Comstock G. The effects of television violence on antisocial behavior: a meta-analysis. Commun Res. 1994;21(4):516–546 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robinson TN. Reducing children’s television viewing to prevent obesity: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;282(16):1561–1567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson JG, Cohen P, Smailes EM, Kasen S, Brook JS. Television viewing and aggressive behavior during adolescence and adulthood. Science. 2002;295(5564):2468–2471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joensson A. TV–a threat or a complement to school? A longitudinal study of the relationship between TV and school. J Educ Television. 1986;12(1):29–38 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimmerman FJ, Glew G, Christakis DA, Katon W. Early cognitive stimulation, emotional support, and television watching as predictors of subsequent bullying among grade-school children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(4):384–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagin DS, Tremblay RE. Parental and early childhood predictors of persistent physical aggression in boys from kindergarten to high school. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(4):389–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ladd GW, Burgess KB. Charting the relationship trajectories of aggressive, withdrawn, and aggressive/withdrawn children during early grade school. Child Dev. 1999;70(4):910–929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brame B, Nagin DS, Tremblay RE. Developmental trajectories of physical aggression from school entry to late adolescence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2001;42(4):503–512 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kingston L, Prior M. The development of patterns of stable, transient, and school-age onset aggressive behavior in young children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(3):348–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedrich LK, Stein AH. Aggressive and prosocial television programs and the natural behavior of preschool children. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 1973;38(4):1–64 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedrich LK, Stein AH. Prosocial television and young children: the effects of verbal labeling and role playing on learning and behavior. Child Dev. 1975;46:27–38 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedrich-Cofer LK, Huston-Stein A, Kipnis DM, Susman EJ, Clewett AS. Environmental enhancement of prosocial television content: effects on interpersonal behavior, imaginative play, and self-regulation in a natural setting. Dev Psychol. 1979;15(6):637–646 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldberg ME, Gorn GJ. Television's impact on preferences for non-white playmates: Canadian Sesame Street inserts. J Broadcasting. 1979;23:27–32 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forge KLS, Phemister S. The effect of prosocial cartoons on preschool children. Child Study J. 1987;17(2):83–88 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mares M, Woodard EH. Prosocial effects on children's social interactions. In: Singer DG, Singer JL, eds. Handbook of Children and the Media. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001:183–206 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silverman LT, Sprafkin JN. The effects of sesame street's prosocial spots on cooperative play between young children. J Broadcasting. 1980;24:135–147 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thakkar RR, Garrison MM, Christakis DA. A systematic review for the effects of television viewing by infants and preschoolers. Pediatrics. 2006;118(5):2025–2031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Comstock G, Paik H. Television and the American Child. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huston AC, Wright JC, Marquis J, Green SB. How young children spend their time: television and other activities. Dev Psychol. 1999;35(4):912–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mendelsohn AL, Berkule SB, Tomopoulos S, et al. Infant television and video exposure associated with limited parent-child verbal interactions in low socioeconomic status households. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(5):411–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Myaing MT, Garrison MM, Rivara FP, Christakis DA. Differences between opt-in and actively recruited participants in a research study. J Clin Med Res. 2011;3(5):68–72 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of mass communication. In: Bryant J, Zillmann D, eds. Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):143–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kotler JC, McMahon RJ. Differentiating anxious, aggressive, and socially competent preschool children: validation of the Social Competence and Behavior Evaluation-30 (parent version). Behav Res Ther. 2002;40(8):947–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vandewater EA, Bickham DS, Lee JH. Time well spent? Relating television use to children's free-time activities. Pediatrics 2006;117(2). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/117/2/e181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Hahn R, Fuqua-Whitley D, Wethington H, et al. Task Force on Community Preventive Services . Effectiveness of universal school-based programs to prevent violent and aggressive behavior: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(suppl 2):S114–S129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Webster-Stratton C, Herbert M. Strategies for helping parents of children with conduct disorders. Prog Behav Modif. 1994;29:121–142 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wesbster-Stratton C. Aggression in young children: services proven to be effecting in reducing aggression. In: Tremblay RE, Barr RG, Peters R, eds. Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development. Montreal, Quebec: Centre of Excellence for Early Childhood Development; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garrison MM, Christakis DA. Reducing exposure to violent TV improves children's sleep. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):492-499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]