Abstract

Astrocytes play a critical role in neurovascular coupling by providing a physical linkage from synapses to arterioles and releasing vaso-active gliotransmitters. We identified a gliotransmitter pathway by which astrocytes influence arteriole lumen diameter. Astrocytes synthesize and release NMDA receptor coagonist, D-serine, in response to neurotransmitter input. Mouse cortical slice astrocyte activation by metabotropic glutamate receptors or photolysis of caged Ca2+ produced dilation of penetrating arterioles in a manner attenuated by scavenging D-serine with D-amino acid oxidase, deleting the enzyme responsible for D-serine synthesis (serine racemase) or blocking NMDA receptor glycine coagonist sites with 5,7-dichlorokynurenic acid. We also found that dilatory responses were dramatically reduced by inhibition or elimination of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and that the vasodilatory effect of endothelial nitric oxide synthase is likely mediated by suppressing levels of the vasoconstrictor arachidonic acid metabolite, 20-hydroxy arachidonic acid. Our results provide evidence that D-serine coactivation of NMDA receptors and endothelial nitric oxide synthase is involved in astrocyte-mediated neurovascular coupling.

Keywords: two-photon, functional hyperemia, Ca2+ uncaging

Cerebral blood flow is regulated by autoregulation, which maintains constant flow during changes in systemic blood pressure, and functional hyperemia, which refers to matched increases in blood flow to brain areas with high neuronal energy demand. Intracerebral arterioles and capillaries account for 30–40% of total cerebrovascular blood flow resistance (1), and therefore, changes to the diameter of small penetrating cortical vessels result in significant changes in local cerebral blood flow. Astrocytes have endfeet directly apposed to these resistance vessels and are critical regulators of arteriole lumen diameter. Astrocyte endfeet express Ca2+-activated K+ channels that gate vasodilatory K+ efflux in response to glutamatergic input (2, 3). Glutamate neurotransmission also causes Ca2+-dependent arachidonic acid (AA) metabolism and release of vasodilatory AA metabolites from astrocytes, including prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), produced by cyclooxygenase (COX), and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs), produced by cytochrome P450 epoxygenase (4–8). Astrocyte-derived AA can also be metabolized by cytochrome P450 ω-hydroxylase to the vasoconstrictor, 20-hydroxyeicosatetranoic acid (20-HETE) (4, 6–8). Ambient tissue oxygen levels dictate whether astrocytes produce AA-dependent vasodilation or vasoconstriction in brain slices and isolated retina (6, 7). Production of 20-HETE is preferred at high pO2 (95% O2 in solution) (6–8), whereas pO2 closer to physiologic levels (20% O2) inhibits prostaglandin-lactate transporter activity, producing high extracellular PGE2 levels (7) and reduced 20-HETE synthesis (6).

Application of glutamate or NMDA directly to the brain surface dilates pial arteries (9, 10) by a mechanism mediated by NMDA receptors (9–12) and neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) (13–15). Although NO is capable of increasing lumen diameter by directly affecting smooth muscle, it may also trigger vasodilation at physiologic pO2 by reducing ω-hydroxylase activity and 20-HETE production, thereby shifting the balance of constrictor and dilator AA metabolites derived from astrocytes (4, 16, 17). In vivo, it was suggested NO derived from nNOS, specifically, reduces 20-HETE levels (17), but there is no further evidence of a specific link between nNOS and astrocyte AA metabolism in neurovascular coupling. Endothelial NOS (eNOS) plays a role in baseline brain vascular tone and pathological hyperemia (13, 18–21), but there has not yet been a connection made between eNOS, astrocyte function, and hyperemic vasodilation.

NMDA receptors are activated by binding of glutamate and a coagonist that binds to a strychnine-insensitive glycine regulatory site (22). D-Serine is more effective than glycine as an NMDA receptor coagonist (23–25) and has a brain distribution that closely parallels that of NMDA receptors (26). In addition, D-serine is extensively distributed in glial cells (26, 27), is released as a gliotransmitter by Ca2+-dependent exocytosis in response to glutamatergic input (28), and contributes to astrocyte–neuron communication (29–31). Given the established role of NMDA receptors in hyperemic blood flow regulation, we hypothesized that astrocyte D-serine is directly involved in regulating the lumen diameter of brain resistance vessels. We showed previously that isolated middle cerebral arteries dilated in response to exogenous glutamate and D-serine treatment by an NMDA receptor-mediated mechanism (32). The goal of the current study was to determine whether endogenous D-serine is involved in astrocyte-mediated neurovascular coupling in cortical penetrating arterioles. We demonstrated that endogenous D-serine contributes to the vasodilatory response produced by direct astrocyte activation. We also provide evidence that NMDA receptors and eNOS are involved in this response, identifying a signal linking astrocytes and eNOS-mediated vasodilation.

Results

Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor Activation Causes D-Serine–Mediated Dilation of Cortical Arterioles.

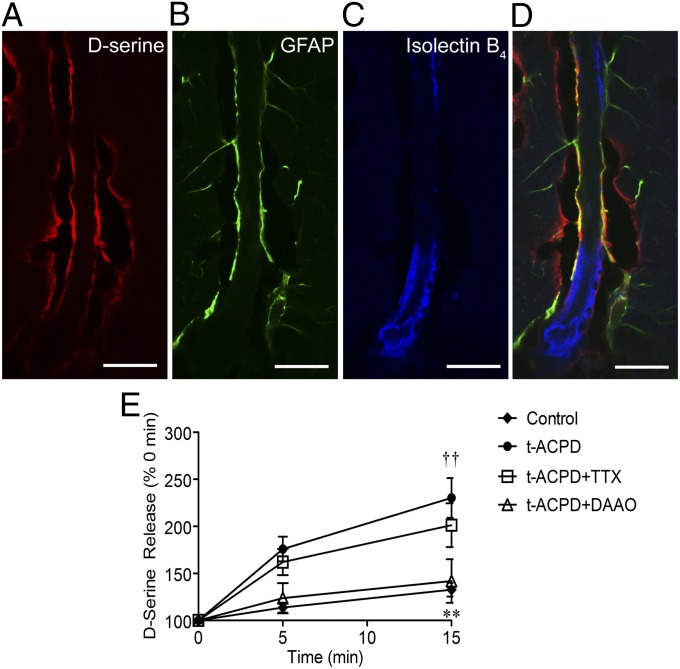

Immunohistochemistry in fixed cortical slices revealed D-serine immunoreactivity in astrocyte endfeet apposed to penetrating arterioles (Fig. 1). D-Serine signal (Fig. 1A) was detected in cells coexpressing the astrocyte marker, GFAP (Fig. 1B), around arterioles labeled with isolectin B4 (Fig. 1C). This suggests there is a D-serine pool in close proximity to cortical supply vessels. Separately, the metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) agonist, (±)-1-aminocyclopentane-trans-1,3-dicarboxylic acid (tACPD), has been shown to increase intracellular astrocyte Ca2+ levels and dilate local arterioles (7, 33), as well as stimulate D-serine release in a Ca2+ and SNARE-protein–dependent manner (28, 34). We confirmed that tACPD treatment of acute cortical slices (100 µM) stimulated significant accumulation of extracellular D-serine after 15 min of exposure using a bulk chemiluminescence assay (Fig. 1E). Pretreatment with the D-serine catabolic enzyme, D-amino acid oxidase (DAAO), significantly reduced extracellular D-serine accumulation, indicating specific detection of D-serine. Tetrodotoxin (TTX) pretreatment had no effect, suggesting neuronal D-serine pools accessible by depolarization (35) are not involved in this response.

Fig. 1.

D-serine localization to perivascular astrocyte endfeet in fixed cortical slices. (A–D) D-serine immunoreactivity (A, red) was localized to perivascular sites colabeled with the astrocyte marker, GFAP (B, green) in glutaraldehyde-fixed cortical slices (30 µm) from 14–19-d-old mice. Cerebrovasculature was labeled with isolectin B4 (C, blue). (D), Overlay of A–C (scale bar, 20 μm). (E) mGluR agonist tACPD (100 µM) induced significant release of D-serine from brain slices compared with untreated controls. Detection was eliminated by coexposure to DAAO (0.1 Units/mL). Data are mean ± SEM; **P < 0.0.01 for tACPD compared with control; †† P < 0.01 for tACPD/TTX compared with control using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test.

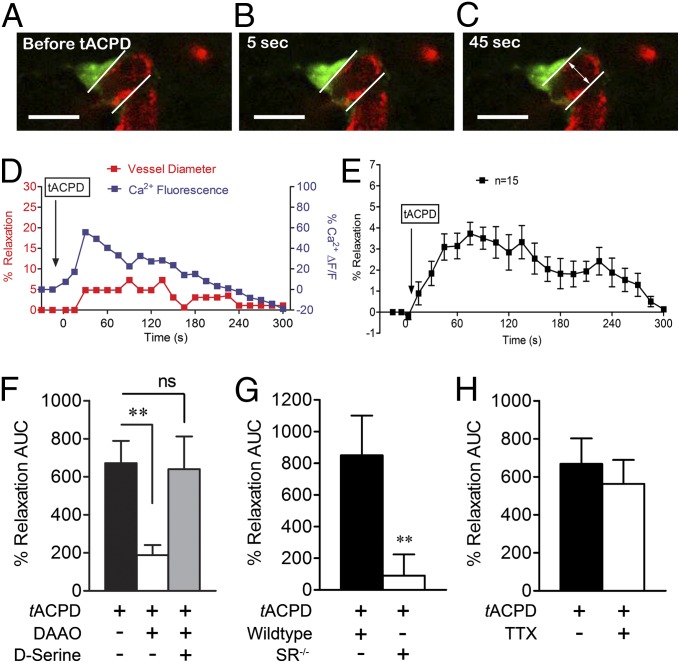

We exposed cortical slices to tACPD and simultaneously monitored perivascular astrocyte Ca2+ and neighboring arteriole diameter in real time using two-photon laser scanning microscopy (Fig. 2 A–C). In slices maintained in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) with 20% O2, tACPD enhanced rhodamine-2 fluorescence in astrocytes in a manner temporally associated with dilatory responses in cortical arterioles (Fig. 2D). tACPD produced a maximal lumen diameter increase of 3.7 ± 0.1%, 75 s after exposure (Fig. 2E; maximal of 4.1 ± 0.8% without fixing the time point). Dilatory responses were assessed as area under the curve (AUC) between time 0 (tACPD addition) and return to baseline (Fig. 2E). Preincubation of slices with DAAO (0.1 units/mL) significantly reduced vasodilation (Fig. 2F), whereas addition of exogenous D-serine to compete for DAAO activity restored vasodilatory responses. tACPD-induced vasodilation in cortical slices isolated from mice lacking the D-serine synthesis enzyme, serine racemase (SR) was dramatically reduced, further indicating an important role for D-serine (Fig. 2G). These experiments demonstrate that perivascular astrocytes contain D-serine that can be released in quantities sufficient to increase arteriolar lumen diameter in glutamatergic neurotransmission simulated by mGluR activation. TTX pretreatment did not affect vasodilatory responses (Fig. 2H), arguing against an effect of D-serine derived from neuronal stores accessed by depolarization.

Fig. 2.

tACPD induces D-serine–dependent cortical vasodilation. Bath application of tACPD (100 µM) elevated astrocyte Ca2+ (green, Rhod 2) and triggered arteriolar (red, isolectin B4) vasodilation in a temporally correlated manner. (A–C) Representative images for a single astrocyte–arteriole pair before tACPD addition (A) and 5 (B) and 45 (C) s after (scale bar, 15 µm). (D) Representative plot of changes in astrocyte Ca2+ (blue) and arteriole diameter (red) after tACPD treatment. (E) Plot of average dilation of 15 vessels after tACPD treatment over 300 s. Data are mean ± SEM. (F), DAAO significantly inhibited vasodilation of arterioles after tACPD application, whereas exogenous D-serine (100 µM) with DAAO recovered the dilatory effect of tACPD. (G) Genetic deletion of SR (SR−/−) eliminated the vasodilatory response to tACPD. (H) TTX did not affect tACPD-induced vasodilation. For G and H, data are mean ± SEM of total AUC for individual plots of percent relaxation versus time. **P < 0.01 using one-way ANOVA with Student Newman–Keuls test (>2 groups) or t tests (2 groups).

Direct Astrocyte Activation Causes D-Serine–Dependent Dilation of Cortical Arterioles.

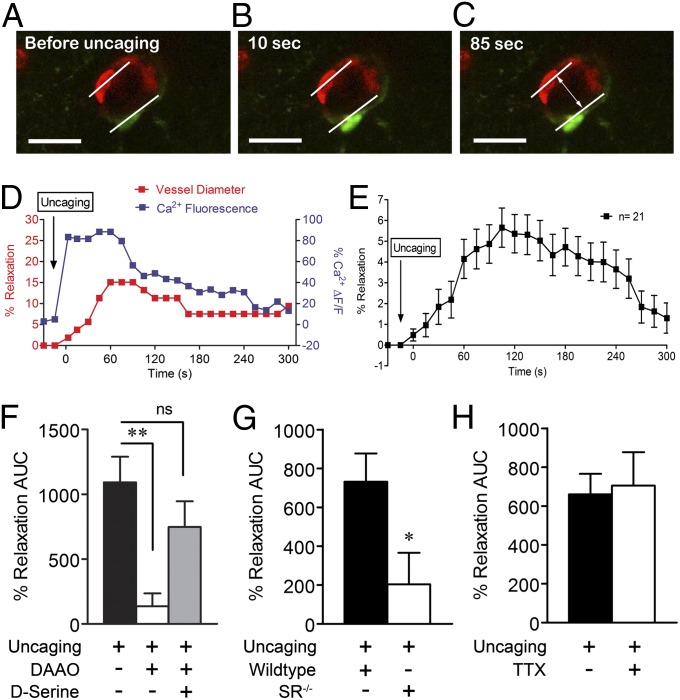

To directly link astrocyte Ca2+ elevations with vasodilatory responses, we stimulated increases in cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels of single rhodamine-2-labeled perivascular astrocytes using flash photolysis of the caged Ca2+ compound, ο-nitrophenyl-EGTA AM (NP-EGTA; Fig. S1). Astrocyte Ca2+ (rhodamine-2) and arteriole diameter were subsequently monitored (Fig. 3 A–C). Astrocyte Ca2+ increases consistently correlated with dilation of neighboring cortical arterioles (Fig. 3D, representative experiment). Average vasodilation peaked at 5.7 ± 0.2%, 105 s after stimulation (Fig. 3B; 7.0 ± 0.9% without fixing the time point). DAAO significantly reduced vasodilation in a manner reversed by addition of exogenous D-serine after flash photolysis (Fig. 3F). Similarly, vasodilation was significantly inhibited by deletion of SR (Fig. 3G). These data demonstrate that endogenous D-serine plays a role in cortical vasodilation resulting from direct activation of a single perivascular astrocyte by Ca2+ uncaging. TTX (1 µM) did not significantly alter vasodilatory responses (Fig. 3H), suggesting neuronal excitation is not necessary for direct astrocyte-mediated vasodilation.

Fig. 3.

Direct astrocyte Ca2+ uncaging leads to D-serine–dependent cortical vasodilation. Flash photolysis of ο-nitrophenyl-EGTA in perivascular astrocyte endfeet stimulated elevation of local Ca2+ levels (green, Rhod 2) in a manner that temporally corresponded with an increase in lumen diameter of a neighboring arteriole (red, isolectin B4). (A–C) Representative images of a single perivascular astrocyte and arteriole are shown before (A) and after (B and C) flash photolysis (scale bar, 15 µm). (D) Representative plot of changes in astrocyte Ca2+ (blue) and arteriole diameter (red) after photolysis. (E) Plot of average dilation of 21 vessels after astrocyte Ca2+ uncaging over 300 s. Data are mean ± SEM. (F) DAAO (0.1 Units/mL) significantly inhibited vasodilation induced by direct astrocyte activation, whereas exogenous D-serine (100 µM) with DAAO recovered the dilatory effect. (G) Genetic deletion of SR (SR−/−) eliminated the vasodilatory response to astrocyte Ca2+ uncaging. (H) TTX (1 µM) did not affect vasodilation induced by astrocyte Ca2+ uncaging. For G and H, data are mean ± SEM of total AUC for individual plots of percent relaxation versus time. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 using one-way ANOVA with Student Newman–Keuls test (>2 groups) or t tests (2 groups).

D-Serine–Dependent Vasodilation Is Dependent on Glutamate Corelease and NMDA Receptors.

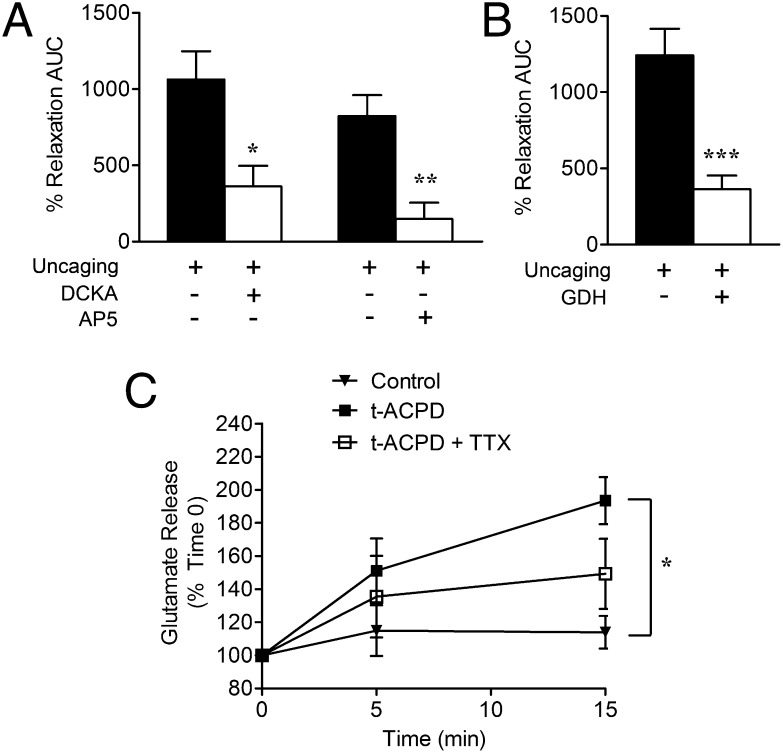

Cortical slices were exposed to the NMDA receptor competitive glycine/D-serine coagonist site antagonist 5,7-dichlorokynurenic acid (DCKA; 100 µM) or the competitive glutamate-site antagonist 2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoate (AP5; 50 µM), before flash photolysis of caged Ca2+. Both DCKA and AP5 significantly reduced vasodilatory responses (Fig. 4A). Preincubation of cortical slices with glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH; 1 U/mL) also attenuated arteriole dilation resulting from flash photolysis (Fig. 4B), indicating that both glutamate and D-serine (Figs. 2 and 3) are involved in astrocyte-mediated vasodilation. In agreement, tACPD caused TTX-independent bulk release of endogenous glutamate from cortical slices (Fig. 4C), supporting the idea that glutamate and D-serine are coreleased from astrocytes and play a joint role in neurovascular coupling.

Fig. 4.

Cortical vasodilation by D-serine is dependent on glutamate and NMDA receptors. (A) tACPD induced significant TTX-insensitive (1 µM) glutamate release, relative to control cortical slices (*P < 0.05 using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni test). (B) GDH (1 U/mL) significantly reduced arteriole vasodilation induced by astrocyte Ca2+ uncaging (***P < 0.001, t test). (C) Competitive NMDA receptor antagonists DCKA (glycine site, 100 µM) and AP5 (glutamate site, 50 µM) significantly blocked arteriole vasodilation induced by direct astrocyte Ca2+ uncaging (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA with Student Newman–Keuls test). All data are mean ± SEM.

Astrocyte-Mediated Vasodilation Is Dependent on PGE2 and eNOS.

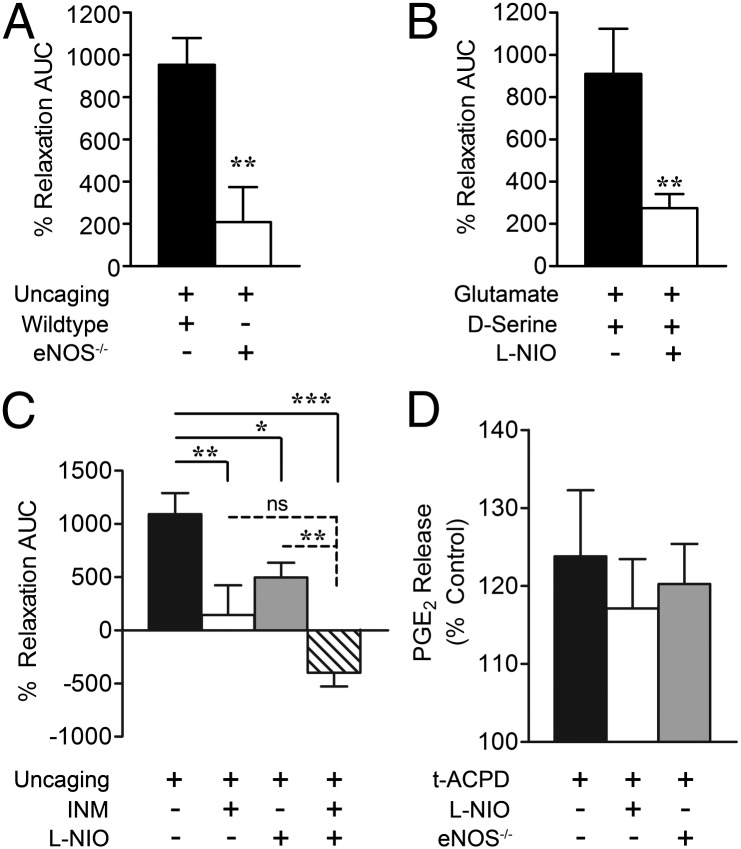

Our data demonstrate that intact endothelium and eNOS are required for D-serine and glutamate to increase lumen diameter in isolated middle cerebral arteries (32). We thus tested the hypothesis that D-serine and glutamate-induced vasodilation in cortical slice arterioles is mediated by eNOS. In response to astrocyte Ca2+ uncaging, genetic deletion of eNOS dramatically attenuated increases in lumen diameter compared with treatment controls (Fig. 5A). We also measured vasodilatory responses to an exogenous glutamate and D-serine mixture (10 µM each with 1 µM TTX) in the presence and absence of the eNOS inhibitor, N5-(1-iminoethyl)-l-ornithine (l-NIO; 3 µM). l-NIO significantly reduced arteriole dilation by glutamate and D-serine (Fig. 5B), directly linking D-serine with eNOS activity and vasodilation in cortical slices.

Fig. 5.

Astrocyte-induced cortical vasodilation is mediated by PGE2 and eNOS. (A) eNOS-null mice displayed reduced cortical vasodilatory efficacy in response to astrocyte Ca2+ uncaging compared with C57 wild-type mice (**P < 0.01, t test). (B) Coapplication of glutamate (10 µM), D-serine (10 µM), and TTX (1 µM) produced cortical slice vasodilation sensitive to inhibition by the eNOS selective antagonist l-NIO (3 µM, **P < 0.01, t test). (C) Both the COX inhibitor INM (100 µM) and eNOS inhibitor l-NIO (3 µM) significantly reduced vasodilation in response to astrocyte Ca2+ uncaging. Combined INM and l-NIO caused significant vasoconstriction in response to astrocyte Ca2+ uncaging (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 using one-way ANOVA with Student Newman–Keuls test). (D) PGE2 release from cortical slices was measured by ELISA 5 min after tACPD treatment and was not significantly affected by treatment with l-NIO (3 µM) or genetic eNOS deletion (ns, P > 0.05 using one-way ANOVA with Student Newman–Keuls test). All data are mean ± SEM.

Several studies have demonstrated that astrocyte-induced cortical vasodilation is mediated by COX-dependent metabolism of AA to PGE2 (5, 7, 33). We therefore tested for PGE2 involvement in our model by using indomethacin (INM; 100 µM) to inhibit COX. INM alone reduced vasodilation produced by astrocyte Ca2+ uncaging by 87% (Fig. 5C). This is not significantly different from the l-NIO-mediated reduction (55%). Combined, INM and l-NIO significantly enhanced the effect of l-NIO alone, producing vasoconstriction in response to astrocyte Ca2+ uncaging (Fig. 5C). tACPD-induced astrocyte activation increased PGE2 levels in a manner independent of l-NIO or genetic eNOS elimination (Fig. 5D), indicating that eNOS does not cause vasodilation by directly influencing PGE2.

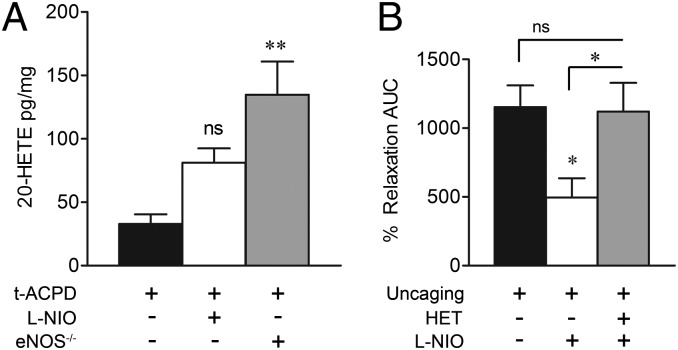

eNOS Causes Vasodilation by Suppressing 20-HETE Production.

There is substantial evidence that NO inhibits production of the vasoconstrictor AA metabolite 20-HETE (36), leading to vasodilation in brain microvasculature (4, 17), but any contribution of eNOS to this pathway is yet to be identified. In our hands, brain slice production of 20-HETE in the presence of tACPD was significantly enhanced in eNOS-null cortical slices (Fig. 6A), demonstrating that eNOS activity suppresses 20-HETE production in this model. To determine whether suppression of 20-HETE participates in eNOS-mediated vasodilation, we examined the effect of eNOS inhibition by l-NIO in the absence of a functional 20-HETE production pathway, suppressed by the CYP4A (ω-hydroxylase) inhibitor N-hydroxy-N'-(4-n-butyl-2-methylphenyl)formamidine (HET0016; 100 nM). Vasodilation induced by astrocyte Ca2+ uncaging was significantly inhibited by l-NIO alone but not in combination with HET0016 (Fig. 6B), suggesting that eNOS vasodilation is dependent on activity of the 20-HETE pathway.

Fig. 6.

eNOS inhibits 20-HETE production. (A) Cortical slice 20-HETE production in response to tACPD was statistically unchanged by l-NIO (ns, P > 0.05) and increased by eNOS deletion (**P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA with Student Newman–Keuls test). (B) Alone, l-NIO (3 µM) significantly reduced cortical vasodilation induced by astrocyte Ca2+ uncaging (*P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Student Newman–Keuls test). This effect was lost in the presence of HET0016 (HET, 100 nM; ns, P > 0.05), which interferes with 20-HETE formation. All data are mean ± SEM.

Discussion

Here, we provided evidence that endogenous D-serine is a mediator of neurovascular coupling. D-Serine was responsible for astrocyte-induced dilation of penetrating cortical arterioles in a manner dependent on coavailability of extracellular glutamate and NMDA receptors. We also demonstrated that astrocyte-mediated cortical vasodilation is at least partially dependent on eNOS-derived suppression of 20-HETE.

Several lines of evidence support involvement of astrocyte D-serine in dilation of penetrating cortical arterioles in brain slices. D-Serine immunoreactivity was identified in perivascular astrocyte endfeet, in agreement with a previous report (26). Also consistent with published data (28), we found that simulating glutamatergic neurotransmission by exposing cortical slices to tACPD caused significant efflux of D-serine into the bathing medium (28). These data together suggest there is a source of D-serine available for regulated release at the neurovascular unit. We then showed that DAAO and SR deletion significantly inhibited dilation of brain slice–penetrating cortical arterioles induced by tACPD. This observation established a critical role for endogenous D-serine in regulating brain vascular lumen diameter, and this role is supported further by the demonstration that vasodilatory effects were mitigated by interfering with specific binding for D-serine in the NMDA receptor complex by DCKA. Because tACPD activates both neuronal and astrocytic mGluRs, we considered the possibility that the vasodilatory effect of D-serine is independent of astrocyte activation by tACPD. Although the failure of TTX to suppress D-serine release and cortical vasodilation argues against this idea, we more precisely ascertained the role of astrocytes in D-serine–mediated vasodilation by using flash photolysis of caged Ca2+ (NP-EGTA) in perivascular astrocyte endfeet. Direct astrocyte activation was sufficient to increase arteriolar lumen diameter in cortical slices. Moreover, uncaging-induced vasodilation was blocked by more than 88% by DAAO and 72% by SR deletion, providing further support for a vasodilatory pathway originating with glutamate neurotransmission and leading to astrocyte Ca2+ elevation, D-serine release from astrocytes, and vascular smooth muscle relaxation.

The impact of observed changes to the lumen diameter on blood flow is an important consideration. Poiseuille’s Law dictates that resistance to blood flow decreases as a function of the fourth power of any increases in lumen diameter. Therefore, a 7% increase in lumen diameter (average achievement with uncaging) reduces resistance by a more impressive magnitude of 24%. In addition, comparisons across experimental conditions are critical because some models use preconstriction paradigms to achieve a much higher magnitude of vasodilation (33, 37). Our observations are consistent with vasodilation magnitudes observed by another group using brain slices maintained without preconstriction at equal aCSF oxygenation (7). These points, coupled with observations that vasodilation in vitro likely underestimates COX-mediated vasodilation seen in pressurized vessels in vivo (5), support speculation that our observed vasodilatory magnitudes in vitro translate into meaningful blood flow changes in vivo.

Our data support a vasodilatory mechanism of D-serine mediated by coactivation of NMDA receptors with glutamate. Again, cortical vasodilation induced by astrocyte Ca2+ uncaging was significantly attenuated by DCKA, directly indicating that activation of NMDA receptor glycine sites is involved. Importantly, this effect was also inhibited by AP5, indicating that occupation of the NMDA receptor glutamate binding site is also required for vasodilation in this paradigm. Paired involvement of glutamate and D-serine is further supported by our observations that tACPD stimulated both glutamate and D-serine release (Figs. 4C and 1E, respectively) and that the presence of the glutamate catabolic enzyme GDH eliminated cortical vasodilation initiated by Ca2+ uncaging. Overall, these results show that both coagonists of NMDA receptors are required for a significant component of astrocyte-induced vasodilation in cortical slices. There is a report that AP5 does not affect cortical vasodilation in response to tACPD (33). Although this is seemingly inconsistent with our results, Zonta et al. (33) used artificial CSF equilibrated with 95% O2, which is a condition that is dramatically different from ours (20%) and favors production of the smooth muscle constrictor 20-HETE (4, 6, 7). This may mask the vasodilatory effects of D-serine and NMDA receptors, making the models difficult to compare appropriately. The cellular source of NMDA receptors responsible for vasodilation in our model is not clear. Our previous work indicates that brain arterial endothelial cells express NMDA receptors capable of initiating a vasodilatory response to extraluminally applied glutamate and D-serine (32). Current data indicate that eNOS contributes to astrocyte-mediated vasodilation and that TTX-sensitive neuronal Na+ channels, and therefore direct vessel innervation (38), are not required for vasodilation downstream of astrocyte activation. All of these observations tempt speculation that endothelial, rather than neuronal, NMDA receptors participate in astrocyte-mediated vasodilation, but definitive experiments have yet to be performed.

A clear conclusion drawn from our current findings is that eNOS participates in astrocyte-mediated dilation of penetrating cortical arterioles. NO is central to NMDA receptor-mediated neurovascular coupling (10, 39, 40), but only a role for nNOS, specifically, has been described (14, 39, 41). Our finding that a mixture of glutamate or NMDA and D-serine can dilate isolated cerebral arteries by an endothelium and eNOS-dependent mechanism (32) gave rise to the hypothesis that eNOS may be involved in vasodilation initiated by astrocyte gliotransmission in situ. In support of this hypothesis, cortical vasodilation induced by astrocyte Ca2+ uncaging was significantly inhibited by l-NIO at a concentration (3 μM) yielding strong selectivity for eNOS (42, 43) and by genetic eNOS deletion. D-serine was also linked directly to eNOS activity in cortical slice arterioles, as l-NIO inhibited vasodilation induced by exogenous application of glutamate/D-serine (10 µM each) in the presence of TTX. In functional hyperemia in vivo, a recent cat study concluded that both nNOS and eNOS participate in vasodilatory responses, with eNOS becoming more prominent at lower levels of neuronal activity and nNOS dominating at higher neuronal activation levels (44). We did not compare the relative roles of eNOS and nNOS in cortical vasodilation induced by tACPD or direct astrocyte activation. Further studies targeting eNOS and nNOS loss of function will assist in determining the relative roles of these isoforms and the cell types in which they are expressed.

Our tACPD and astrocyte Ca2+ uncaging paradigms closely resemble those used in several previous studies demonstrating the astrocyte-mediated cortical or hippocampal vasodilation is mediated by the COX metabolite PGE2 (5–7, 33). Therefore, it is important to address how discovery of a role for eNOS fits with the established COX-mediated mechanism. We found agreement with previous studies (5–7) by showing that COX metabolites also contributed to astrocyte-mediated vasodilation, as INM inhibited vascular responses to Ca2+ uncaging. Addition of INM to l-NIO treatment resulted in a loss of vasodilatory effect greater than that achieved with l-NIO alone and actually produced smooth muscle constriction, suggesting that eNOS and COX pathways are additive. Additivity is further supported by the observation that astrocyte-activated eNOS has no direct effect on PGE2 levels (Fig. 5C). It has been reported that NO modulates the vascular effects of AA metabolites by inhibiting cytochrome P450 enzymes that produce 20-HETE and EETs (4). In our hands, cortical 20-HETE content in response to tACPD treatment was significantly enhanced in eNOS−/− slices. This demonstrates that eNOS-derived NO inhibits 20-HETE production and suggests that vasodilation may result from NO-induced suppression of the 20-HETE influence on smooth muscle tone. Support for functional suppression of the vascular effects of 20-HETE comes from experiments using l-NIO and an inhibitor of CYP4A ω-hydroxylase (HET0016), which is the enzyme responsible for 20-HETE formation. The ability of l-NIO to attenuate vasodilatory responses to astrocyte Ca2+ uncaging was lost in the presence of HET0016, suggesting that the vasodilatory role of eNOS-derived NO depends on an active 20-HETE production pathway. Overall, our data support dual astrocyte-mediated vasodilatory mechanisms working together. We and others demonstrated that astrocyte activation leads to direct COX-dependent, PGE2-mediated increases in cortical arteriole lumen diameter. Our data support the idea that astrocyte activation also leads to eNOS activity and suppression of 20-HETE levels, thus facilitating the direct PGE2-mediated vasodilation.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Animals.

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, unless otherwise noted. Animal procedures were approved by the Office of Research Ethics and Compliance Animal Care Committee for the Bannatyne Campus, University of Manitoba. SR deletion mice were generated from C57BL/6-derived embryonic stem cells transfected with the gene-targeting vector containing C57BL/6 mouse genomic DNA and were expanded by crossing with C57BL/6 mice (45). Wild-type littermate controls were used for experiments comparing control to SR knockout phenotypes. eNOS deletion mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories and bred at the R.O. Burrell Lab at St. Boniface Hospital Research. C57BL/6 was used as the control strain.

Brain Slice Preparation and Two-Photon Laser Scanning Microscopy.

Brains from CD1 or C57BL/6 mice (14–19 d old) were placed in ice-cold cutting buffer (2.5 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM MgSO4, 5 mM CaCl2, 26 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM glucose, 230 mM sucrose) bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Slices were cut on a vibrating blade microtome (350 µm) and were then maintained in aCSF (126 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 26 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM glucose) equilibrated with 95% O2, 5% CO2, and heated to 35 °C. After 1 h, slices were loaded with the Ca2+ indicator dye, Rhodamine-2 AM (10 µM; Invitrogen), and Griffonia simplicifolia 1 Isolectin B4 tagged with Alexa Fluor 488 (5 µg/mL; Invitrogen). Two-photon imaging proceeded on the stage of an upright microscope in aCSF equilibrated with 20% O2, 5% CO2, and 75% N2. Scans were performed using an excitation wavelength of 800 nm, delivered through an Ultima multiphoton scanhead, with dual galvanometers for imaging and uncaging (Prairie Technologies), by a pulsed Ti-sapphire laser (Coherent Inc.). For astrocyte Ca2+ uncaging, cortical slices were incubated with ο-nitrophenyl-EGTA AM (10 µM; Invitrogen) for 1 h. Cytoplasmic photoliberation of Ca2+ was achieved using functional mapping software (TriggerSync, Prairie Technologies) to guide a 700 nm/100 ms laser pulse through a voltage-controlled pockels cell. Images were analyzed every 15 s using PrairieView software to determine vessel lumen diameter, as marked by isolectin staining. Changes in vessel lumen diameter were correlated with astrocyte rhodamine-2 Ca2+ fluorescence intensity changes, which were measured using ImageJ.

D-Serine and Glutamate Release Assays.

Acute brain slices were incubated in aCSF equilibrated with 20% O2/5% CO2 and then stimulated with tACPD (100 µM) for 15 min. Some slices were pretreated with DAAO (0.1 U/mL) or TTX (1 µM) for 20 min. During tACPD stimulation, samples of aCSF were collected at 0 min, 5 min, or 15 min for measurement of D-serine and glutamate concentrations. D-serine release was measured by chemiluminescent assay, as described previously with minor modification (46, 47). We mixed 10 µl of each sample with 100 µl of aCSF containing 100 mM Tris⋅HCI, pH 8.8, 20 U/mL peroxidase, and 8 µl of luminol. Samples were incubated 15 min to decrease background signal of luminol, and then 10 µl of DAAO (75 U/mL) was added, where applicable. Chemiluminescence kinetics was recorded for 5 min at room temperature using a TD-20/20 Luminometer (Turner Designs). D-serine concentrations were calculated based on a standard curve. Glutamate release was determined at each time point by using Amplex Red Glutamic Acid/Glutamate Oxidase Assay Kit (Invitrogen).

PGE2 and 20-HETE ELISAs.

Acute brain slices were incubated in aCSF equilibrated with 20% O2/5% CO2 and stimulated with tACPD (100 µM) for 5 min. Some slices were pretreated with TTX (1 µM) with or without l-NIO (3 µM) for 20 min. PGE2 release in aCSF was measured using the PGE2 enzyme immunoassay (EIA) Kit (Cayman). For 20-HETE, brain slices were lysed and 20-HETE production was measured by 20-HETE ELISA Kit (Detroit R&D, Inc.).

D-Serine Immunohistochemistry.

D-serine immunostaining was modified from the procedure by Schell et al. (1995) (26). Brains from 14–19-d-old CD1 mice were fixed (5% glutaraldehyde, 0.5% PFA, 0.2% Na2S2O5, 0.1 M Na2PO4 buffer at pH 7.4) for 24 h and cryopreserved in 30% sucrose. Tissue was then snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen cooled n-hexane and cut into 30 µm sections. Slices were reduced for 20 min at room temperature in 0.2% Na2S2O5 and 0.5% NaBH4 in 0.1 M Tris-buffered saline (TBS; pH 7.4) and rinsed with 0.2% Na2S2O5 in TBS for 45 min. Tissue was blocked in 4% goat serum, 0.2% Triton X-100, and 0.2% Na2S2O5 in 0.1 M TBS for 2 h and then incubated in 0.1 M TBS (pH 7.2) with 2% goat serum, 0.1% Triton X-100, and primary antibodies: rabbit anti-D-serine (Millipore), mouse anti-GFAP, and G. simplicifolia 1 Isolectin B4 tagged with Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) for 48 h. Secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor 633 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (Invitrogen) and Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (Invitrogen) were used for visualization of D-serine and GFAP. Images were collected with a Zeiss LSM510 laser-scanning microscope.

Data Analysis.

AUC was calculated from percent vessel relaxation versus time plots. AUC among experimental groups were compared using t test for two groups or one-way ANOVA with Student Newman–Keuls post hoc test for three or more groups. The time course of glutamate and D-serine release from slices was analyzed by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc tests.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Ayumi Tanaka for SR deletion mouse preparation. Research was supported by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. J.L.S. was supported by a student award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1215929110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Iadecola C. Neurovascular regulation in the normal brain and in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5(5):347–360. doi: 10.1038/nrn1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Filosa JA, et al. Local potassium signaling couples neuronal activity to vasodilation in the brain. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(11):1397–1403. doi: 10.1038/nn1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Girouard H, et al. Astrocytic endfoot Ca2+ and BK channels determine both arteriolar dilation and constriction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(8):3811–3816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914722107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Metea MR, Newman EA. Glial cells dilate and constrict blood vessels: A mechanism of neurovascular coupling. J Neurosci. 2006;26(11):2862–2870. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4048-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takano T, et al. Astrocyte-mediated control of cerebral blood flow. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(2):260–267. doi: 10.1038/nn1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mishra A, Hamid A, Newman EA. Oxygen modulation of neurovascular coupling in the retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(43):17827–17831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110533108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordon GR, Choi HB, Rungta RL, Ellis-Davies GC, MacVicar BA. Brain metabolism dictates the polarity of astrocyte control over arterioles. Nature. 2008;456(7223):745–749. doi: 10.1038/nature07525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mulligan SJ, MacVicar BA. Calcium transients in astrocyte endfeet cause cerebrovascular constrictions. Nature. 2004;431(7005):195–199. doi: 10.1038/nature02827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busija DW, Leffler CW. Dilator effects of amino acid neurotransmitters on piglet pial arterioles. Am J Physiol. 1989;257(4 Pt 2):H1200–H1203. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.4.H1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faraci FM, Breese KR. Nitric oxide mediates vasodilatation in response to activation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in brain. Circ Res. 1993;72(2):476–480. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.2.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhardwaj A, et al. P-450 epoxygenase and NO synthase inhibitors reduce cerebral blood flow response to N-methyl-D-aspartate. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279(4):H1616–H1624. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.4.H1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simandle SA, et al. Piglet pial arteries respond to N-methyl-D-aspartate in vivo but not in vitro. Microvasc Res. 2005;70(1–2):76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iadecola C. Regulation of the cerebral microcirculation during neural activity: Is nitric oxide the missing link? Trends Neurosci. 1993;16(6):206–214. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90156-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fergus A, Lee KS. Regulation of cerebral microvessels by glutamatergic mechanisms. Brain Res. 1997;754(1–2):35–45. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma J, Ayata C, Huang PL, Fishman MC, Moskowitz MA. Regional cerebral blood flow response to vibrissal stimulation in mice lacking type I NOS gene expression. Am J Physiol. 1996;270(3 Pt 2):H1085–H1090. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.3.H1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alonso-Galicia M, Hudetz AG, Shen H, Harder DR, Roman RJ. Contribution of 20-HETE to vasodilator actions of nitric oxide in the cerebral microcirculation. Stroke. 1999;30(12):2727–2734, discussion 2734. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.12.2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu X, et al. Interaction of nitric oxide, 20-HETE, and EETs during functional hyperemia in whisker barrel cortex. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295(2):H619–H631. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01211.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma J, et al. L-NNA-sensitive regional cerebral blood flow augmentation during hypercapnia in type III NOS mutant mice. Am J Physiol. 1996;271(4 Pt 2):H1717–H1719. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.4.H1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pereira de Vasconcelos A, Riban V, Wasterlain C, Nehlig A. Role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in cerebral blood flow changes during kainate seizures: A genetic approach using knockout mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;23(1):219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hlatky R, et al. The role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the cerebral hemodynamics after controlled cortical impact injury in mice. J Neurotrauma. 2003;20(10):995–1006. doi: 10.1089/089771503770195849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Endres M, Laufs U, Liao JK, Moskowitz MA. Targeting eNOS for stroke protection. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27(5):283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dingledine R, Borges K, Bowie D, Traynelis SF. The glutamate receptor ion channels. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51(1):7–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fadda E, Danysz W, Wroblewski JT, Costa E. Glycine and D-serine increase the affinity of N-methyl-D-aspartate sensitive glutamate binding sites in rat brain synaptic membranes. Neuropharmacology. 1988;27(11):1183–1185. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(88)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsui T, et al. Functional comparison of D-serine and glycine in rodents: The effect on cloned NMDA receptors and the extracellular concentration. J Neurochem. 1995;65(1):454–458. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65010454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shleper M, Kartvelishvily E, Wolosker H. D-serine is the dominant endogenous coagonist for NMDA receptor neurotoxicity in organotypic hippocampal slices. J Neurosci. 2005;25(41):9413–9417. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3190-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schell MJ, Molliver ME, Snyder SH. D-serine, an endogenous synaptic modulator: Localization to astrocytes and glutamate-stimulated release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(9):3948–3952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolosker H, Blackshaw S, Snyder SH. Serine racemase: A glial enzyme synthesizing D-serine to regulate glutamate-N-methyl-D-aspartate neurotransmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(23):13409–13414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mothet JP, et al. Glutamate receptor activation triggers a calcium-dependent and SNARE protein-dependent release of the gliotransmitter D-serine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(15):5606–5611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408483102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panatier A, et al. Glia-derived D-serine controls NMDA receptor activity and synaptic memory. Cell. 2006;125(4):775–784. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henneberger C, Papouin T, Oliet SH, Rusakov DA. Long-term potentiation depends on release of D-serine from astrocytes. Nature. 2010;463(7278):232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature08673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Y, et al. Contribution of astrocytes to hippocampal long-term potentiation through release of D-serine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(25):15194–15199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2431073100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LeMaistre JL, et al. Coactivation of NMDA receptors by glutamate and D-serine induces dilation of isolated middle cerebral arteries. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32(3):537–547. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zonta M, et al. Neuron-to-astrocyte signaling is central to the dynamic control of brain microcirculation. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6(1):43–50. doi: 10.1038/nn980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martineau M, Galli T, Baux G, Mothet JP. Confocal imaging and tracking of the exocytotic routes for D-serine-mediated gliotransmission. Glia. 2008;56(12):1271–1284. doi: 10.1002/glia.20696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenberg D, et al. Neuronal release of D-serine: A physiological pathway controlling extracellular D-serine concentration. FASEB J. 2010;24(8):2951–2961. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-147967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roman RJ. P-450 metabolites of arachidonic acid in the control of cardiovascular function. Physiol Rev. 2002;82(1):131–185. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00021.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koide M, Bonev AD, Nelson MT, Wellman GC. Inversion of neurovascular coupling by subarachnoid blood depends on large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(21):E1387–E1395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121359109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tong XK, Hamel E. Basal forebrain nitric oxide synthase (NOS)-containing neurons project to microvessels and NOS neurons in the rat neocortex: Cellular basis for cortical blood flow regulation. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12(8):2769–2780. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bari F, Errico RA, Louis TM, Busija DW. Interaction between ATP-sensitive K+ channels and nitric oxide on pial arterioles in piglets. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16(6):1158–1164. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199611000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meng W, Tobin JR, Busija DW. Glutamate-induced cerebral vasodilation is mediated by nitric oxide through N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. Stroke. 1995;26(5):857–862, discussion 863. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.5.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Faraci FM, Brian JE., Jr 7-Nitroindazole inhibits brain nitric oxide synthase and cerebral vasodilatation in response to N-methyl-D-aspartate. Stroke. 1995;26(11):2172–2175, discussion 2176. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.11.2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chinellato A, Froldi G, Caparrotta L, Ragazzi E. Pharmacological characterization of endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase inhibitors in isolated rabbit aorta. Life Sci. 1998;62(6):479–490. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)01144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rees DD, Palmer RM, Schulz R, Hodson HF, Moncada S. Characterization of three inhibitors of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in vitro and in vivo. Br J Pharmacol. 1990;101(3):746–752. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb14151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Labra C, et al. Different sources of nitric oxide mediate neurovascular coupling in the lateral geniculate nucleus of the cat. Front Syst Neurosci. 2009;3:9. doi: 10.3389/neuro.06.009.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miya K, et al. Serine racemase is predominantly localized in neurons in mouse brain. J Comp Neurol. 2008;510(6):641–654. doi: 10.1002/cne.21822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolosker H, et al. Purification of serine racemase: Biosynthesis of the neuromodulator D-serine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(2):721–725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhuang Z, et al. EphrinBs regulate D-serine synthesis and release in astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2010;30(47):16015–16024. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0481-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.