Abstract

AIM: To conduct a meta-analysis to compare Roux-en-Y (R-Y) gastrojejunostomy with gastroduodenal Billroth I (B-I) anastomosis after distal gastrectomy (DG) for gastric cancer.

METHODS: A literature search was performed to identify studies comparing R-Y with B-I after DG for gastric cancer from January 1990 to November 2012 in Medline, Embase, Science Citation Index Expanded and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials in The Cochrane Library. Pooled odds ratios (OR) or weighted mean differences (WMD) with 95%CI were calculated using either fixed or random effects model. Operative outcomes such as operation time, intraoperative blood loss and postoperative outcomes such as anastomotic leakage and stricture, bile reflux, remnant gastritis, reflux esophagitis, dumping symptoms, delayed gastric emptying and hospital stay were the main outcomes assessed. Meta-analyses were performed using RevMan 5.0 software (Cochrane library).

RESULTS: Four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 9 non-randomized observational clinical studies (OCS) involving 478 and 1402 patients respectively were included. Meta-analysis of RCTs revealed that R-Y reconstruction was associated with a reduced bile reflux (OR 0.04, 95%CI: 0.01, 0.14; P < 0.00 001) and remnant gastritis (OR 0.43, 95%CI: 0.28, 0.66; P = 0.0001), however needing a longer operation time (WMD 40.02, 95%CI: 13.93, 66.11; P = 0.003). Meta-analysis of OCS also revealed R-Y reconstruction had a lower incidence of bile reflux (OR 0.21, 95%CI: 0.08, 0.54; P = 0.001), remnant gastritis (OR 0.18, 95%CI: 0.11, 0.29; P < 0.00 001) and reflux esophagitis (OR 0.48, 95%CI: 0.26, 0.89; P = 0.02). However, this reconstruction method was found to be associated with a longer operation time (WMD 31.30, 95%CI: 12.99, 49.60; P = 0.0008).

CONCLUSION: This systematic review point towards some clinical advantages that are rendered by R-Y compared to B-I reconstruction post DG. However there is a need for further adequately powered, well-designed RCTs comparing the same.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, Distal gastrectomy, Roux-en-Y, Billroth I, Reconstruction, Meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is one of the most common cancers worldwide with approximately 989 600 new cases and 738 000 deaths per year, accounting for about 8 percent of new cancers[1]. Surgical resection is still the only option for providing definitive treatment of this malignant disease[2]. Due to the early diagnosis of gastric cancer, there has been a significant improvement in the long-term survival of patients undergoing surgery within the past decade[3]. Surgeons have therefore focused on improving the patients’ postoperative quality of life by modifying the surgical technique and the type of reconstruction performed after distal gastrectomy (DG)[4]. The three mainly used reconstruction techniques after DG are: (1) gastroduodenal anastomosis (Billroth-I, B-I); (2) gastrojejunal anastomosis (Billroth-II, B-II); and (3) Roux-en-Y (R-Y) gastrojejunostomy. Although both B-I and R-Y anastomoses are recognized as standard reconstruction procedures after DG[5], it is yet to be established, which of these is the better of the two. The B-I reconstruction has been commonly performed, because of its technical simplicity, with only one anastomotic site and maintaining physiological intestinal continuity[5,6]. However, gastroesophageal and duodenogastric reflux are well documented in patients who undergo this type of reconstruction following DG[7], and severe gastritis, esophagitis and gastric cancer can subsequently occur[8-11]. The aforementioned complications seriously affect postoperative quality of life of patients undergoing DG[12].

For several decades, R-Y reconstruction has been the preferred method to prevent reflux gastritis, esophagitis and decrease probability of gastric cancer recurrence[9,10,13,14]. However, the choice of surgical reconstruction is often based on personal preferences of surgeons, e.g., majority of surgeons in the East favor a B-I reconstruction, while R-Y is the procedure of choice in the West[9,15]. Although a few studies have directly compared B-I and R-Y techniques, these studies have failed to reach a consensus and establish which method is the best choice after DG for gastric carcinoma. Thus it is difficult to choose a particular type of reconstruction, based on the current evidence base. We therefore sought to compare the perioperative outcomes and postoperative complications of patients undergoing R-Y and B-I reconstruction after DG for gastric cancer by undertaking a meta-analysis of published data.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search

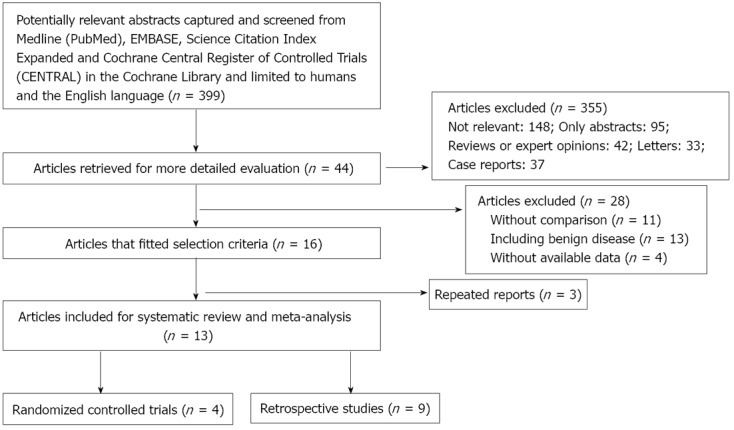

A comprehensive literature search of Medline, Embase, Science Citation Index Expanded and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials in the Cochrane Library between January 1990 and November 2012 was carried out for comparing R-Y and B-I reconstructions after DG for gastric cancer. Medical subject headings as well as keywords “Roux-en-Y”; “Billroth-I”; “reconstruction”; “distal gastrectomy”; “gastric cancer” and “stomach cancer” were used. All abstract supplements from published literature were searched manually. Relevant papers were also identified from the reference lists of previous papers, including those obtained through the search of abstracts and recent international meetings. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomized observational clinical studies (OCS) with full-text descriptions were included. Final inclusion of articles was determined by consensus; when this failed, a third author adjudicated. The results of the search strategy are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram depicting the process of identification and inclusion of selected studies.

Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria

Two authors identified and screened the search findings for potentially eligible studies. Inclusion criteria were: (1) English language articles published in peer-reviewed journals; (2) Human trials of patients with gastric cancer undergoing DG as the main procedure; (3) Studies with at least one of the outcomes mentioned; and (4) When similar studies were reported by the same institution or author, either the better quality study or the more recent publication was included. Following studies were excluded: (1) Abstracts, letters, editorials, expert opinions, reviews and case reports; (2) Studies without available data; (3) Studies without control group; and (4) Studies including patients with benign disease.

Outcomes of interest

Perioperative outcomes and postoperative complications were evaluated. Operation time, intraoperative blood loss and hospital stay were the main perioperative outcomes to be assessed. Postoperative complications included anastomotic leakage and stricture, bile reflux, remnant gastritis, reflux esophagitis, dumping symptoms and delayed gastric emptying.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were extracted by two independent observers using standardized forms. RCTs were qualitatively analyzed using Jadad scoring system[16]. Non-randomized OCS were similarly evaluated using Newcastle-Ottawa scoring system[17]. The quality assessment was also carried out by two independent observers and is displayed in Tables 1 and 2. Quantitative data extracted from the selected studies including: population characteristics (study year, country, design, gender, mean age) and outcome parameters (operation time, intraoperative blood loss, hospital stay, anastomotic leakage and stricture, bile reflux, remnant gastritis, reflux esophagitis, dumping symptoms and delayed gastric emptying.

Table 1.

Quality assessment of the included randomized controlled studies based on the Jadad scoring system

Table 2.

Newcastle-Ottawa scoring system for nonrandomized comparative studies

| Ref. | Selection star | Comparability star1 | Outcome star | Total star |

| Osugi et al[9] | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Shinoto et al[10] | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Nunobe et al[13] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Fukuhara et al[14] | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Kojima et al[21] | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Namikawa et al[22] | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Tanaka et al[23] | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Kumagai et al[24] | 3 | 2 | 1 | 6 |

| Kim et al[25] | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

Factors considered: Age, gender; American Society of Anesthesiologists grading and tumor stage.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analyses were performed by using Review Manager Version 5.0 software (The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, United Kingdom). For categorical variables, treatment effects were expressed as odds ratio (OR) with corresponding 95%CIs. For continuous variables, treatment effects were expressed as weighted mean difference (WMD) with corresponding 95%CI. Meta-analyses were performed using fixed- or random-effects model, depending on the absence or presence of significant heterogeneity. Heterogeneity was evaluated using the χ2 test, with a P < 0.1 was considered significant; I2 values were used for the evaluation of statistical heterogeneity[18]. If the test rejected the assumption of homogeneity of studies, then the random effects analysis was performed[19]. Sensitivity analyses were also performed by removing individual studies from the data set and analyzing the effect on the overall results to identify sources of significant heterogeneity. Funnel plots were constructed to evaluate potential publication bias.

RESULTS

Study characteristics

There were 399 papers relevant to the search terms. Sixteen studies[9,10,13,14,20-31] met the inclusion criteria. Four studies had previously been reported by the same institution[27-29,31]. Three studies were excluded[27-29], however, one study had some outcomes which we can include[31]. Finally, four RCTs[20,26,27,31], and 9 OCS[9,10,13,14,21-25] with 478 and 1402 patients respectively were included. All these studies have been carried out in Japan and Korea. The number of patients in the included studies ranged from 43 to 424. Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of included studies in the meta-analysis

| Ref. | Country | Design | Group | Patients (n) | Male/female (n) | Mean age (yr) |

| Osugi et al[9] | Japan | Retro | R-Y | 18 | 13/5 | 60.2 |

| B-I | 25 | 12/13 | 64.7 | |||

| Shinoto et al[10] | Japan | Retro | R-Y | 20 | NR | 63 ± 12 |

| B-I | 43 | NR | 63 ± 9 | |||

| Nunobe et al[13] | Japan | Retro | R-Y | 182 | 117/65 | 58.8 |

| B-I | 203 | 127/76 | 58.7 | |||

| Fukuhara et al[14] | Japan | Retro | R-Y | 29 | 23/6 | 56.1 |

| B-I | 41 | 19/22 | 66.0 | |||

| Ishikawa et al[20] | Japan | RCT | R-Y | 24 | 17/7 | 64 (43-80) |

| B-I | 26 | 19/7 | 61 (34-84) | |||

| Kojima et al[21] | Japan | Retro | R-Y | 68 | 43/25 | 62.8 ± 12.2 |

| B-I | 65 | 48/17 | 62.0 ± 8.9 | |||

| Namikawa et al[22] | Japan | Retro | R-Y | 38 | 22/16 | 71 (41-80) |

| B-I | 47 | 25/22 | 72 (33-86) | |||

| Tanaka et al[23] | Japan | Retro | R-Y | 51 | 34/17 | 65.2 |

| B-I | 50 | 34/16 | 66.2 | |||

| Kumagai et al[24] | Japan | Retro | R-Y | 95 | 74/21 | 62.7 (42-81) |

| B-I | 329 | 197/132 | 63.5 (29-90) | |||

| Kim et al[25] | South Korea | Retro | R-Y | 26 | 21/5 | ≥ 60 (9) |

| B-I | 72 | 54/18 | ≥ 60 (41) | |||

| Lee et al[26] | South Korea | RCT | R-Y | 47 | 28/19 | 58.5 ± 10.7 |

| B-I | 49 | 31/18 | 60.0 ± 11.6 | |||

| Imamura et al[27] or Hirao et al[31] | Japan | RCT | R-Y | 169 | 115/54 | 63.9 ± 10.5 |

| B-I | 163 | 105/58 | 64.4 ± 9.3 |

Retro: Retrospective observational study; RCT: Randomized controlled trial; R-Y: Roux-en-Y; B-I: Billroth-I.

Meta-analysis results

Included RCTs and OCS were analyzed separately to determine outcome measures in the study groups. All the results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Meta-analysis of outcomes of interest

| Outcome of interest | Studies | Patients (n) | OR/WMD | 95%CI | P value |

| RCT | |||||

| Operation time | 3 | 478 | 40.02 | 13.93, 66.11 | 0.003 |

| Intraoperative blood loss | 3 | 478 | 26.99 | -9.35, 63.33 | 0.15 |

| Hospital stay | 3 | 478 | 2.96 | -0.00, 5.93 | 0.05 |

| Anastomotic leakage | 3 | 478 | 0.56 | 0.12, 2.66 | 0.47 |

| Anastomotic stricture | 3 | 478 | 1.79 | 0.52, 6.13 | 0.36 |

| Bile reflux | 2 | 145 | 0.04 | 0.01, 0.14 | < 0.00 001 |

| Reflux esophagitis | 3 | 458 | 0.49 | 0.20, 1.23 | 0.13 |

| Remnant gastritis | 2 | 363 | 0.43 | 0.28, 0.66 | 0.000 |

| Delayed gastric emptying | 2 | 363 | 2.31 | 0.12 | 44.41 |

| OCS | |||||

| Operation time | 4 | 718 | 31.3 | 12.99, 49.60 | 0.001 |

| Intraoperative blood loss | 3 | 620 | 26.9 | -46.54, 100.34 | 0.47 |

| Hospital stay | 2 | 522 | 1.40 | -0.17, 2.97 | 0.08 |

| Anastomotic leakage | 5 | 813 | 1.26 | 0.40, 3.97 | 0.70 |

| Anastomotic stricture | 3 | 658 | 0.94 | 0.31, 2.89 | 0.91 |

| Bile reflux | 6 | 757 | 0.21 | 0.08, 0.54 | 0.001 |

| Reflux esophagitis | 5 | 719 | 0.48 | 0.26, 0.89 | 0.02 |

| Remnant gastritis | 6 | 784 | 0.18 | 0.11, 0.29 | < 0.00 001 |

| Dumping symptoms | 4 | 347 | 0.59 | 0.32, 1.12 | 0.11 |

| Delayed gastric emptying | 4 | 701 | 0.95 | 0.24, 3.74 | 0.94 |

RCT: Randomized controlled trials; OCS: Non-randomized observational clinical studies; OR: Odds ratio; WMD: Weighted mean differences.

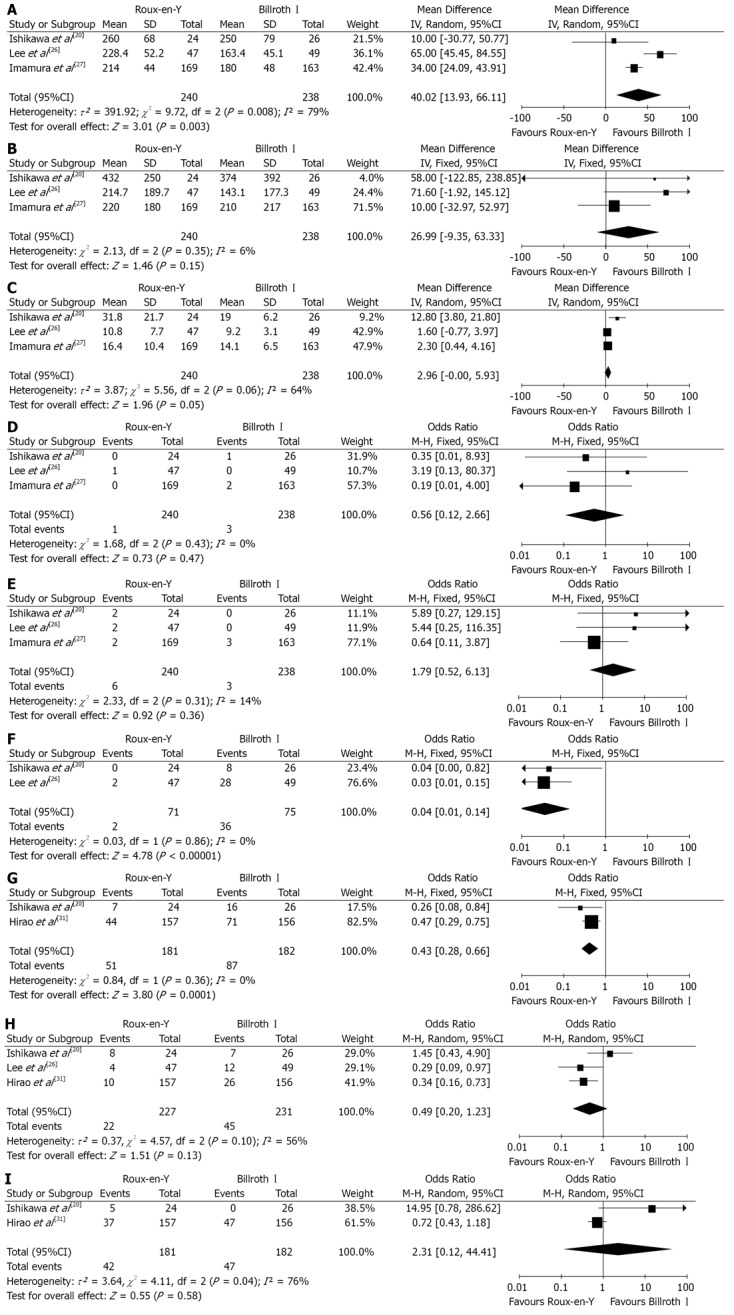

RCTs comparison: To date, 4 RCTs have been undertaken to compare R-Y with B-I reconstruction[20,26,27,31]. However, two studies[27,31] have same study populations. All studies had a clear description of the sample size calculation and were found to be of high quality according to Jadad scoring system. The detailed results of meta-analysis are given in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Roux-en-Y versus Billroth I-randomized controlled trials comparison. A: Operation time; B: Intraoperative blood loss; C: Hospital stay; D: Anastomotic leakage; E: Anastomotic stricture; F: Bile reflux; G: Remnant gastritis; H: Reflux esophagitis; I: Delayed gastric emptying. Pooled weighted mean difference (WMD) or odds ratio (OR) with 95%CI was calculated using the fixed-or random effects model.

Meta-analysis revealed that R-Y reconstruction was associated with a significant reduction in the incidence of bile reflux (OR 0.04, 95%CI: 0.01, 0.14; P < 0.00001) and remnant gastritis (OR 0.43, 95%CI: 0.28, 0.66; P = 0.0001). No significant differences were observed between the groups in terms of intraoperative blood loss (OR 26.99, 95%CI: -9.35, 63.33; P = 0.15), hospital stay (OR 2.96, 95%CI: -0.00, 5.93; P = 0.05), anastomotic leakage (OR 0.56, 95%CI: 0.12, 2.66; P = 0.47), stricture (OR 1.79, 95%CI: 0.52, 6.13; P = 0.92), reflux esophagitis (OR 0.49, 95%CI: 0.20, 1.23; P = 0.13) and delayed gastric emptying (OR 2.31, 95%CI: 0.12, 44.41; P = 0.58). However, B-I reconstruction method took significantly less time to perform as compared to R-Y reconstruction (WMD 40.02, 95%CI: 13.93, 66.11; P = 0.003).

Only one study[20] reported incidence of dumping symptoms. The incidence of dumping symptoms was not significantly different between the two groups (OR 1.09, 95%CI: 0.14, 8.42; P = 0.93).

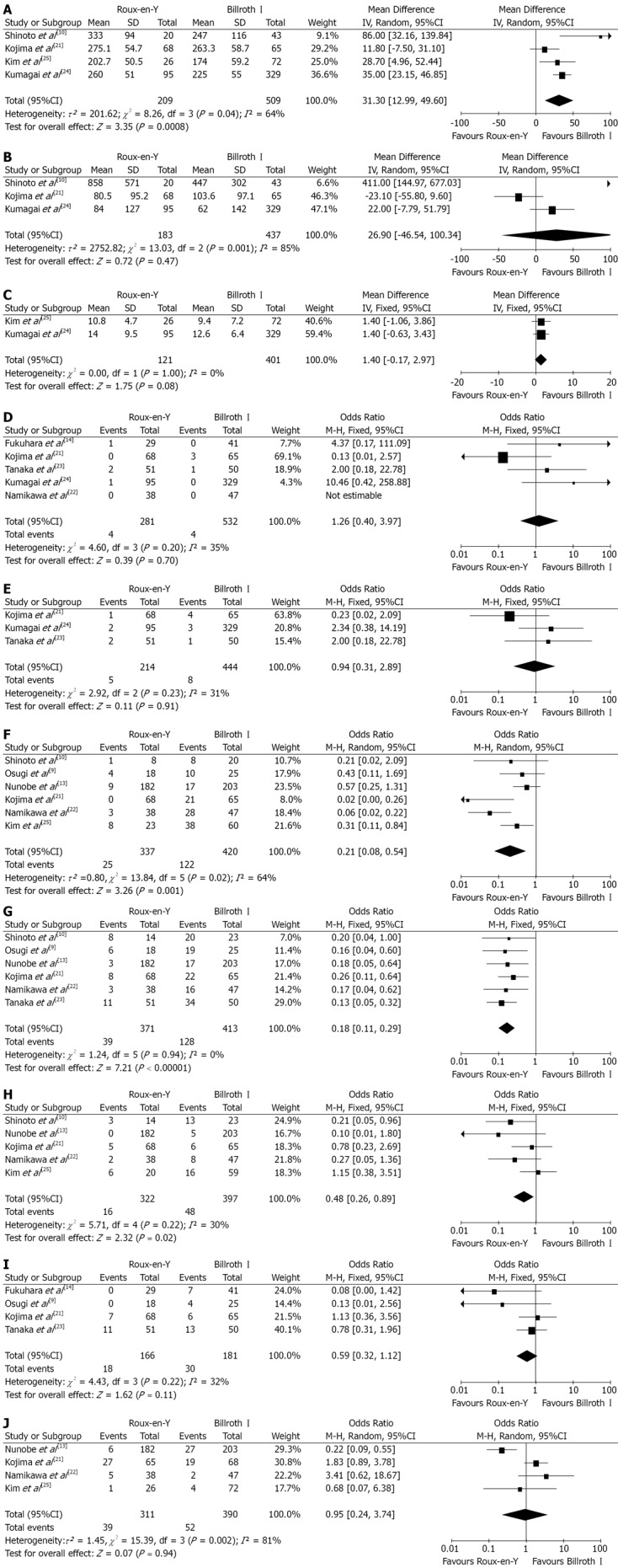

OCS comparison: Nine OCS were included[9,10,13,14,21-25]. Forest plots are illustrated in Figure 3. Results suggested that R-Y reconstruction had significantly lower incidence of bile reflux (OR 0.21, 95%CI: 0.08, 0.54; P = 0.001), remnant gastritis (OR 0.18, 95%CI: 0.11, 0.29; P < 0.00 001) and reflux esophagitis (OR 0.48, 95%CI: 0.26, 0.89; P = 0.02). No significant differences were found between the two reconstructive methods in terms of intraoperative blood loss (WMD 26.90, 95%CI: -46.54, 100.34; P = 0.47), hospital stay (WMD 1.40, 95%CI: -0.17, 2.97; P = 0.08), anastomotic leakage (OR 1.26, 95%CI: 0.40, 3.97; P = 0.70), stricture (OR 0.94, 95%CI: 0.31, 2.89; P = 0.91), dumping symptoms (OR 0.59, 95%CI: 0.32, 1.12; P = 0.11) and delayed gastric emptying (OR 0.95, 95%CI: 0.24, 3.74; P = 0.94). Results also suggest that B-I reconstruction require shorter operation time (WMD 31.30, 95%CI: 12.99, 49.60; P = 0.0008) as compared to R-Y procedure.

Figure 3.

Roux-en-Y versus Billroth I-observational non-randomized clinical studie comparison. A: Operation time; B: Intraoperative blood loss; C: Hospital stay; D: Anastomotic leakage; E: Anastomotic stricture; F: Bile reflux; G: Remnant gastritis; H: Reflux esophagitis; I: Dumping symptoms; J: Delayed gastric emptying. Pooled weighted mean difference (WMD) or odds ratio (OR) with 95%CI was calculated using the fixed-or random effects model.

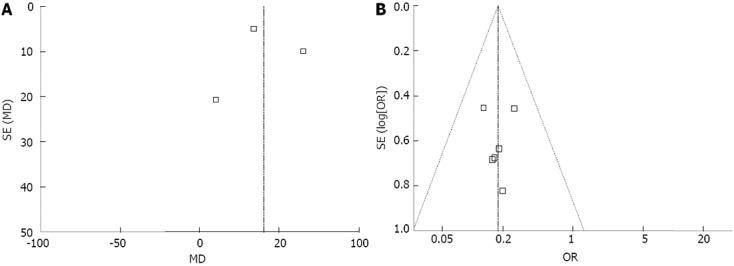

Publication bias

Funnel plot analysis of the studies in the meta-analysis reporting was performed on operation time after DG in RCTs and remnant gastritis in OCS respectively. None of the studies lay outside the limits of the 95%CIs, and there was no evidence of publication bias among the studies (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Funnel plot. A: Operation time-randomized controlled trial; B: Remnant gastritis-observational clinical studies. None of the studies lay outside the limits of the 95%CIs, and there was no evidence of publication bias.

DISCUSSION

Surgical intervention plays a vital role in the survival of patients with resectable gastric cancer. However, there seems to be lack of consensus within surgeons with regards to the choice of reconstructive procedure after DG. The ideal gastrointestinal reconstruction procedure should minimize postoperative morbidity and improve quality of life[32]. In current surgical practice, B-I and R-Y procedures are the commonly used reconstruction techniques following resection of distal stomach. To the best of our knowledge, B-I reconstruction has commonly been employed after DG for gastric cancer due to its simplicity, physiological advantage of allowing food to pass through the duodenum and ease of postoperative endoscopy allowing access to the papilla of Vater[33,34]. However, two most common drawbacks of the B-I anastomosis, remnant gastritis and reflux esophagitis, as a consequence of the absence of the pyloric sphincter which allows reflux of duodenal contents into the remnant stomach and esophagus have been well reported[35]. Furthermore, unregulated release of chyme into the duodenum results in rapid gastric emptying which manifests as dumping syndrome[36]. It is important to note that reflux of duodenal contents into the esophagus is strongly associated with Barrett’s esophagus or esophageal cancer and remnant stomach cancer after gastrectomy[37-39].

Traditionally R-Y reconstruction has been the reconstruction method of choice in total gastrectomy[34] and is being increasingly used to prevent duodenogastric and gastroesophageal reflux in DG[10,14,21]. The potential advantages of improved postoperative quality of life take precedence over the possible increased risk of postoperative complications due to two gastrointestinal anastomoses and increased operating time, when considering R-Y reconstruction.

Based on our analysis, which only includes high quality RCTs and OCS, we have addressed this issue, to the best of our effort, of the most appropriate gastrointestinal reconstruction following DG. It is important to note that the results come from a small number of RCTs and therefore, have to be interpreted with caution. Overall analyses for RCTs comparing R-Y with B-I reconstruction favor R-Y method in terms of preventing postoperative bile reflux and remnant gastritis, although we found no significant difference in reflux esophagitis between the two groups. The angle of His is significantly larger in patients who undergo B-I reconstruction compared to those with R-Y and this may be a factor contributing to reduced incidence of reflux symptoms in the latter group[22,28]. We may not have detected an existing difference due to the smaller sample size of the included studies. As only one RCT[20] evaluated incidences of dumping syndrome, descriptive analysis was used, and no difference was found between the two groups with regards to dumping syndrome.

The operating time was significantly shorter in B-Igroup compared to R-Y group, which can be explained by the additional anastomosis in R-Y reconstruction. Although it has been previously reported that anastomotic leak is higher in B-I reconstruction, possibly due to excessive devascularization of duodenal stump and tension on the anastomosis[20,21,27], we found no difference in the rate of anastomotic leak within the two groups. It may be largely due to the use of gastrointestinal stapling devices and the refinement of technique.

Similarly, analysis of pooled data from the OCS, revealed a reduced incidence of bile reflux, remnant gastritis, reflux esophagitis and prolonged operative time in the R-Y reconstruction group. Consequently, based on the above findings, we can conclude that R-Y reconstruction following DG is likely to be superior to B-I reconstruction not only in preventing bile reflux and remnant gastritis, but also reflux esophagitis (OCS analysis only), as it reduces duodenogastric and gastroesophageal reflux[13,28].

We also analyzed data regarding intraoperative bleeding and duration of hospitalization and found no significant difference in either of these parameters within the two groups, although one would expect an earlier recovery of gastrointestinal function in R-Y reconstruction group.

This review does have some limitations and hence the results should be interpreted with a degree of caution. Firstly, most data are extracted from OCS, with fewer RCT’s making it difficult to make firm conclusions. In addition, several important outcomes including remnant gastritis, dumping symptoms and delayed gastric emptying have not been reported adequately in the RCTs. It is important to mention that we were unable to analyze important outcomes including quality of life and incidence of gastric carcinoma in the gastric remnant due to lack of available data. We would therefore propose well-designed RCTs with adequate follow-up and emphasis on assessing important outcomes to clarify ambiguities surrounding the use of these reconstruction methods.

In summary, our systematic review demonstrates that RY reconstruction is likely to be more effective in preventing gastroesophageal reflux or duodenogastric reflux as compared to B-I. Furthermore, we have shown that based on results from RCTs and OCS, RY reconstruction may be used safely without increasing anastomotic leakage, anastomotic stricture and intraoperative bleeding.

In conclusion, this systematic review points towards some clinical advantages that are rendered by R-Y compared to B-I reconstruction post DG. However there is a need for further adequately powered, well-designed RCTs comparing the same.

COMMENTS

Background

Currently, Billroth I (B-I) and Roux-en-Y (R-Y) reconstructions are commonly performed after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. However, deciding which of these reconstruction procedures is superior, remains controversial. Therefore, in order to help arrive at a possible consensus, the authors conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to compare the clinical efficacy and safety of B-I versus R-Y reconstruction following distal gastrectomy (DG) for gastric cancer.

Research frontiers

In order to compare the safety and effectiveness of the B-I and R-Y reconstructions, operative outcomes including operation time, intraoperative blood loss and postoperative outcomes such as anastomotic leakage and stricture, bile reflux, remnant gastritis, reflux esophagitis, dumping symptoms, delayed gastric emptying and hospital stay were included in this study.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Although existing randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and retrospective comparative studies have concluded that R-Y reconstruction could prevent gastroesophageal and duodenogastric reflux following DG, there was a need to further assess the clinical advantages of R-Y and B-I reconstruction based on high-level evidence. This meta-analysis reports that the R-Y reconstruction has some clinical advantages in reducing the incidence of bile reflux and remnant gastritis compared to the B-I technique. Also, R-Y reconstruction does not significantly increase postoperative complications.

Applications

This study shows that R-Y reconstruction following DG for gastric cancer has some clinical advantages compared with B-I reconstruction. However, taking into account the limited number of studies, further adequately powered and well-designed RCTs should be undertaken to investigate the same.

Terminology

Following distal gastrectomy, three methods, namely, (1) gastroduodenal anastomosis or B-I; (2) gastrojejunal anastomosis or Billroth-II; and (3) R-Y gastrojejunostomy are mainly used for gastrointestinal tract reconstruction.

Peer review

This is an interesting study, which can point out to some extent, the direction in gastrointestinal tract reconstruction for the future gastrointestinal surgeon.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer Shi HY S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Lu YJ

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim JP. Current status of surgical treatment of gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2002;79:79–80. doi: 10.1002/jso.10050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roukos DH. Current advances and changes in treatment strategy may improve survival and quality of life in patients with potentially curable gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6:46–56. doi: 10.1007/s10434-999-0046-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakajima T. Gastric cancer treatment guidelines in Japan. Gastric Cancer. 2002;5:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s101200200000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshino K. [History of gastric cancer surgery] Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 2000;101:855–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weil PH, Buchberger R. From Billroth to PCV: a century of gastric surgery. World J Surg. 1999;23:736–742. doi: 10.1007/pl00012379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pääkkönen M, Aukee S, Syrjänen K, Mäntyjärvi R. Gastritis, duodenogastric reflux and bacteriology of the gastric remnant in patients operated for peptic ulcer by Billroth I operation. Ann Clin Res. 1985;17:32–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richter JE. Duodenogastric Reflux-induced (Alkaline) Esophagitis. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2004;7:53–58. doi: 10.1007/s11938-004-0025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osugi H, Fukuhara K, Takada N, Takemura M, Kinoshita H. Reconstructive procedure after distal gastrectomy to prevent remnant gastritis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:1215–1218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shinoto K, Ochiai T, Suzuki T, Okazumi S, Ozaki M. Effectiveness of Roux-en-Y reconstruction after distal gastrectomy based on an assessment of biliary kinetics. Surg Today. 2003;33:169–177. doi: 10.1007/s005950300039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miwa K, Hasegawa H, Fujimura T, Matsumoto H, Miyata R, Kosaka T, Miyazaki I, Hattori T. Duodenal reflux through the pylorus induces gastric adenocarcinoma in the rat. Carcinogenesis. 1992;13:2313–2316. doi: 10.1093/carcin/13.12.2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Svensson JO. Duodenogastric reflux after gastric surgery. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1983;18:729–734. doi: 10.3109/00365528309182087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nunobe S, Okaro A, Sasako M, Saka M, Fukagawa T, Katai H, Sano T. Billroth 1 versus Roux-en-Y reconstructions: a quality-of-life survey at 5 years. Int J Clin Oncol. 2007;12:433–439. doi: 10.1007/s10147-007-0706-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fukuhara K, Osugi H, Takada N, Takemura M, Higashino M, Kinoshita H. Reconstructive procedure after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer that best prevents duodenogastroesophageal reflux. World J Surg. 2002;26:1452–1457. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6363-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adachi Y, Shiraishi N, Shiromizu A, Bandoh T, Aramaki M, Kitano S. Laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy compared with conventional open gastrectomy. Arch Surg. 2000;135:806–810. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.7.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishikawa M, Kitayama J, Kaizaki S, Nakayama H, Ishigami H, Fujii S, Suzuki H, Inoue T, Sako A, Asakage M, et al. Prospective randomized trial comparing Billroth I and Roux-en-Y procedures after distal gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma. World J Surg. 2005;29:1415–1420; discussion 1421. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7830-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kojima K, Yamada H, Inokuchi M, Kawano T, Sugihara K. A comparison of Roux-en-Y and Billroth-I reconstruction after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy. Ann Surg. 2008;247:962–967. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31816d9526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Namikawa T, Kitagawa H, Okabayashi T, Sugimoto T, Kobayashi M, Hanazaki K. Double tract reconstruction after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer is effective in reducing reflux esophagitis and remnant gastritis with duodenal passage preservation. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2011;396:769–776. doi: 10.1007/s00423-011-0777-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanaka S, Matsuo K, Matsumoto H, Maki T, Nakano M, Sasaki T, Yamashita Y. Clinical outcomes of Roux-en-Y and Billroth I reconstruction after a distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: What is the optimal reconstructive procedure? Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:257–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumagai K, Hiki N, Nunobe S, Jiang X, Kubota T, Aikou S, Watanabe R, Tanimura S, Sano T, Kitagawa Y, et al. Different features of complications with Billroth-I and Roux-en-Y reconstruction after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:2145–2152. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1683-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim TG, Hur H, Ahn CW, Xuan Y, Cho YK, Han SU. Efficacy of Roux-en-Y Reconstruction Using Two Circular Staplers after Subtotal Gastrectomy: Results from a Pilot Study Comparing with Billroth-I Reconstruction. J Gastric Cancer. 2011;11:219–224. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2011.11.4.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee MS, Ahn SH, Lee JH, Park do J, Lee HJ, Kim HH, Yang HK, Kim N, Lee WW. What is the best reconstruction method after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer? Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1539–1547. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-2064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imamura H, Takiguchi S, Yamamoto K, Hirao M, Fujita J, Miyashiro I, Kurokawa Y, Fujiwara Y, Mori M, Doki Y. Morbidity and mortality results from a prospective randomized controlled trial comparing Billroth I and Roux-en-Y reconstructive procedures after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. World J Surg. 2012;36:632–637. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1408-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Namikawa T, Kitagawa H, Okabayashi T, Sugimoto T, Kobayashi M, Hanazaki K. Roux-en-Y reconstruction is superior to billroth I reconstruction in reducing reflux esophagitis after distal gastrectomy: special relationship with the angle of his. World J Surg. 2010;34:1022–1027. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0452-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inokuchi M, Kojima K, Yamada H, Kato K, Hayashi M, Motoyama K, Sugihara K. Long-term outcomes of Roux-en-Y and Billroth-I reconstruction after laparoscopic distal gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16:67–73. doi: 10.1007/s10120-012-0154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takiguchi S, Yamamoto K, Hirao M, Imamura H, Fujita J, Yano M, Kobayashi K, Kimura Y, Kurokawa Y, Mori M, et al. A comparison of postoperative quality of life and dysfunction after Billroth I and Roux-en-Y reconstruction following distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: results from a multi-institutional RCT. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15:198–205. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0098-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirao M, Takiguchi S, Imamura H, Yamamoto K, Kurokawa Y, Fujita J, Kobayashi K, Kimura Y, Mori M, Doki Y; Osaka University Clinical Research Group for Gastroenterological Study. Comparison of Billroth I and Roux-en-Y Reconstruction after Distal Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer: One-year Postoperative Effects Assessed by a Multi-institutional RCT. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012:Oct 28 [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2704-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piessen G, Triboulet JP, Mariette C. Reconstruction after gastrectomy: which technique is best? J Visc Surg. 2010;147:e273–e283. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim BJ, O’Connell T. Gastroduodenostomy after gastric resection for cancer. Am Surg. 1999;65:905–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumagai K, Shimizu K, Yokoyama N, Aida S, Arima S, Aikou T. Questionnaire survey regarding the current status and controversial issues concerning reconstruction after gastrectomy in Japan. Surg Today. 2012;42:411–418. doi: 10.1007/s00595-012-0159-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kubo M, Sasako M, Gotoda T, Ono H, Fujishiro M, Saito D, Sano T, Katai H. Endoscopic evaluation of the remnant stomach after gastrectomy: proposal for a new classification. Gastric Cancer. 2002;5:83–89. doi: 10.1007/s101200200014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bühner S, Ehrlein HJ, Thoma G, Schumpelick V. Canine motility and gastric emptying after subtotal gastrectomy. Am J Surg. 1988;156:194–200. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(88)80065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sato T, Miwa K, Sahara H, Segawa M, Hattori T. The sequential model of Barrett’s esophagus and adenocarcinoma induced by duodeno-esophageal reflux without exogenous carcinogens. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wetscher GJ, Hinder RA, Smyrk T, Perdikis G, Adrian TE, Profanter C. Gastric acid blockade with omeprazole promotes gastric carcinogenesis induced by duodenogastric reflux. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:1132–1135. doi: 10.1023/a:1026615905170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldstein SR, Yang GY, Curtis SK, Reuhl KR, Liu BC, Mirvish SS, Newmark HL, Yang CS. Development of esophageal metaplasia and adenocarcinoma in a rat surgical model without the use of a carcinogen. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:2265–2270. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.11.2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]