Autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay (ARSACS) was first described in the French-Canadian founder population of Quebec in 1978, but genetically confirmed patients have now been reported in individuals from Europe and Japan. Ataxia, dysarthria, spasticity with extensor plantar reflexes, distal muscle wasting, sensorimotor neuropathy and horizontal gaze-evoked nystagmus constitute the most frequent progressive neurological signs. Neuroimaging reveals atrophy of the superior vermis, cervical spinal cord, and cerebral cortex.1 SACS is the most frequent gene associated with ARSACS.2

Previous authors reported that retinal hypermyelinated fibres observed in funduscopy are a minor diagnostic criterion for ARSACS that may identify patients with early-onset cerebellar ataxia and characteristic pontine abnormalities.2 3 We found patients with full ophthalmological examination and retinal nerve-fibre layer (RNFL) photographs showing significant increases in RNFL thickness compared to healthy subjects, but not the myelinated fibres radiating from the optic disk described by previous authors. In addition, digital imaging technologies such as optical coherence tomography to measure peripapillary RNFL thickness and provide retinal images show an increase in the RNFL density in these patients.

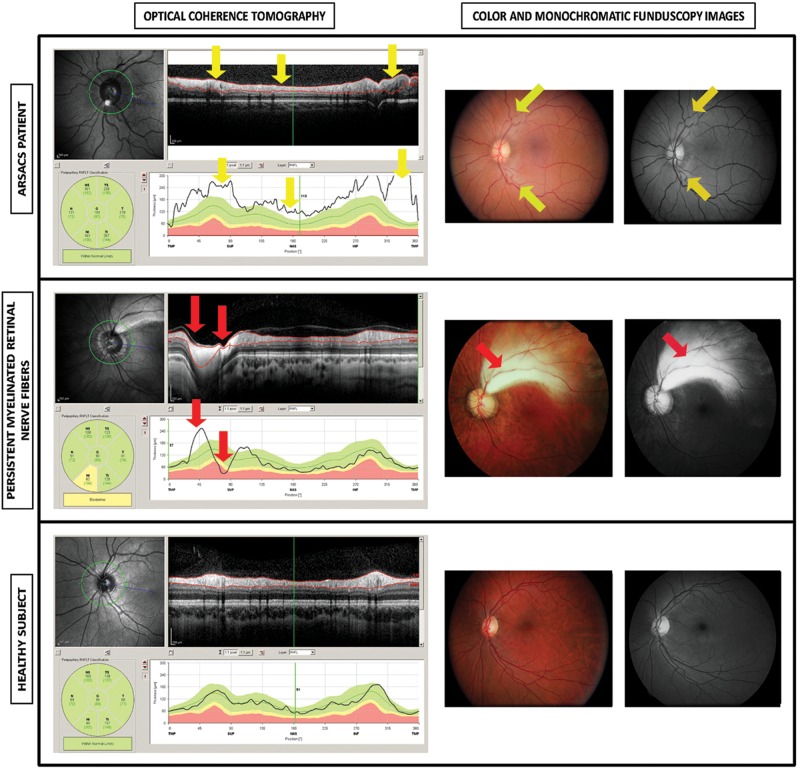

These findings suggest that RNFL hypertrophy in ARSACS patients was interpreted as hypermyelinated retinal fibres in previous reports, and thus the ARSACS diagnostic criteria, particularly with regard to retinal alterations, should be revised. Increases in RNFL density cause retinal streaks observed in the funduscopy exam that may be confused with hypermyelinated fibres, but the physiopathology, clinical manifestations and optical coherence tomography images and measurements are different (figure 1).4–6

Figure 1.

Optical coherence tomography, monochromatic funduscopy images and stereophotographs in left eye from a patient with Spastic Ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay (ARSACS), in left eye with hypermyelinated retinal fibres, and in left eye from a healthy subject. The optical coherence tomography of an eye from an ARSACS patient shows a regular increase of retinal nerve fibre layer thickness in all quadrants (yellow arrows). Notice the values of retinal nerve fibre layer thickness (below), uniformly above the green (95% normal range) zone around the nerve optic and the high average thickness (193 microns). Colour funduscopy image of the same patient shows the characteristic telltale yellow discoloration of this disease while the monochromatic photograph (red free procedure) illustrates an increased visibility of the retinal nerve fibre layer. The optical coherence tomography of an eye with Persistent Myelinated Retinal Nerve Fibres shows a localised thickening of the retinal nerve-fibre layer in the temporal superior area (red arrow) while the rest of the layer remains between the normal limits (green area below). The colour and monochromatic funduscopy images of the abovementioned subject with Persistent Myelinated Retinal Nerve Fibres showed that the myelinated nerve fibres are localised in the superior temporal area showing a white-yellowish tone, whereas the rest of the area surrounding the optic disc is normal. The eye of a healthy subject shows no alterations, localised or diffuse thickening, in all tests: optical coherence tomography, colour funduscopy image and monochromatic photograph.

The SACS gene is involved in nerve fibre development, so ARSACS patients may tend to have hypermyelinated retinal fibres, but re-evaluation of the published articles that some of the images that were considered to show myelinated fibres radiating from the optic disk by previous authors actually shown an increase in the number of retinal nerve fibres (figure 1).

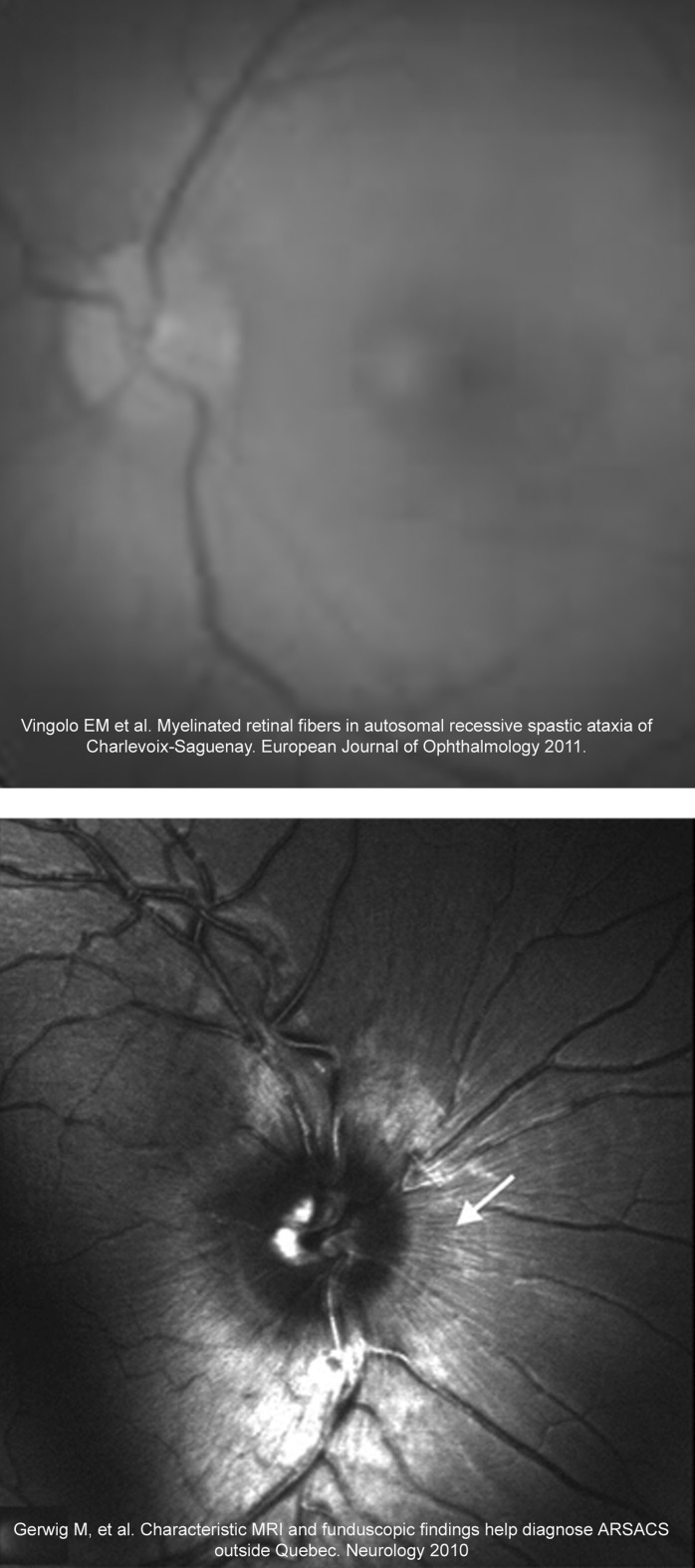

In addition, our hypothesis of RNFL hypertrophy is strengthened by the following findings: tensor diffusion sequences indicate that the hypointense striation corresponds with hyperplasia of the pontocerebellar fibres, which leads to abnormally thick middle cerebellar peduncles;5 6 T2 and T2-fluid attenuation inversion recovery-weighted MRI sequences reveal cerebellar atrophy and a hypointense linear striation at the pons;5 6 ultrastructural observations do not corroborate the notion that hypermyelinated fibres constitute the basic pathophysiology of the retinal abnormities in ARSACS patients;4 genetic studies indicate that SACS functions in nerve fibre development; and nerve biopsies in patients published to date reveal only a depletion of myelinated fibres, and not hypermyelinated fibres (figure 2).4

Figure 2.

Examples of previously published funduscopy images from Spastic Ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay (ARSACS) patients that probably were mistakenly considered to show hypermyelinated retinal fibres. A complete neuro-ophthalmological examination including stereophotographs, retinal nerve fibre photographs and analysis with digital image analysis devices such as optical coherence tomography in these ARSACS patients may demonstrate that they present increased retinal nerve fibre layer density and thickness instead hypermyelinated retinal fibres.

Our results suggest that the retinal streaks are caused by increases in RNFL density, but diagnostic histology of pathological specimens from deceased patients are needed to confirm it. The most recent studies in ARSACS patients suggest a role for the SACS gene in nerve fibre development, causing RNFL hypertrophy and alterations in the central nervous system.

In our opinion, some of the fundus images described as showing hypermyelinated retinal fibres are actually showing increased thickness of the RNFL as in our patients2 3 (figure 1). Therefore, we recommend that experts review these published photographs and perform a complete ophthalmological examination based on stereophotographs, RNFL photographs and analysis with digital image analysis devices.

Footnotes

Contributors: EG-M, LEP, JG, VP, AF, JML have made a substantive intellectual contribution to the submitted manuscript (design and conceptualisation of the study and manuscript, analysis and interpretation of the data and revising the manuscript). These authors have given final approval of the version to be published.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Comité ético de Investigación clínica de Aragón (CEICA).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Open Access: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 3.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/

References

- 1. Dupre N, Bouchard JP, Brais B, et al. Hereditary ataxia, spastic paraparesis and neuropathy in the French-Canadian population. Can J Neurol Sci 2006;33:149–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gerwig M, Krüger S, Kreuz FR, et al. ARSACS outside Quebec haracteristic MRI and funduscopic findings help diagnose. Neurology 2010;75:2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vingolo EM, Di Fabio R, Salvatore S, et al. Myelinated retinal fibers in autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay. Eur J Neurol 2011;18:1187–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pablo LE, Garcia-Martin E, Gazulla J, et al. J. Retinal nerve fiber hypertrophy in ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay patients. Mol Vis 2011;17:1871–6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gazulla J, Vela AC, Marín MA, et al. Is the ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay a developmental disease? Med Hypotheses 2011;77:347–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gazulla J, Benavente I, Vela AC, et al. New findings in the ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay. J Neurol 2012;259:869–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]