Abstract

The ELR+-CXCL chemokines have been described typically as potent chemoattractants and activators of neutrophils during the acute phase of inflammation. Their role in atherosclerosis, a chronic inflammatory vascular disease, has been largely unexplored. Using a mouse model of atherosclerosis, we found that CXCL5 expression was upregulated during disease progression, both locally and systemically, but was not associated with neutrophil infiltration. Unexpectedly, inhibition of CXCL5 was not beneficial but rather induced a significant macrophage foam cell accumulation in murine atherosclerotic plaques. Additionally, we demonstrated that CXCL5 modulated macrophage activation, increased expression of the cholesterol efflux regulatory protein ABCA1, and enhanced cholesterol efflux activity in macrophages. These findings reveal a protective role for CXCL5, in the context of atherosclerosis, centered on the regulation of macrophage foam cell formation.

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is a disease in which chronic inflammation plays a fundamental role. Activated macrophages accumulate in atherosclerotic lesions and contribute not only to the initiation phase but also to the development, progression, and the complication stages of the disease (1). Chemokines, cytokines that attract and activate leukocytes, are implicated in all stages of atherosclerosis and as such have been proposed as potential therapeutic targets (2). Substantial evidence has incriminated the CCL2 and CX3CL1 chemokines, which recruit and stimulate monocytes/macrophages, in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis (1).

Although it is known that ELR+-CXCL chemokines, in particular CXCL1 and CXCL2, are induced during atherosclerosis (3–5), their exact functional contribution to the development of the pathology has not been ascertained. Indeed, while the ELR+-CXCL chemokines have been identified as potent and specific attractants of neutrophils in acute inflammation (2), whether this effect underlies their role in chronic diseases such as atherosclerosis is uncertain. One study, however, has put forward the hypothesis that the ELR+-CXCL receptor CXCR2 is involved in the accumulation of macrophages in advanced atherosclerotic plaques leading to lesion progression (6). The fact that CXCL1 alone has a similar but less pronounced effect (7) points toward the implication of alternative CXCR2 ligands in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. However, CXCL5, which has recently been shown to participate in obesity-induced insulin resistance (8), has received little attention in other obesity-related pathologies. We therefore set ourselves to investigate its expression and function in atherosclerosis.

Results and Discussion

Upregulation of CXCL5 in atherosclerosis.

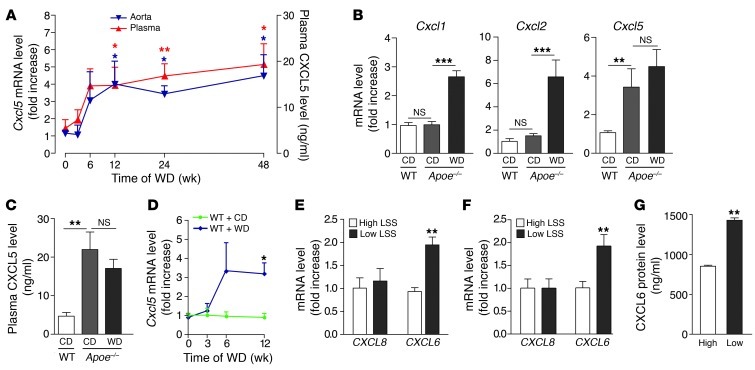

In atherosclerosis-prone Apoe–/– mice fed a Western diet (WD), CXCL5 expression was upregulated in both aorta and plasma and remained elevated up to 48 weeks (Figure 1A). As previously observed (3, 5), expression of CXCL1 and CXCL2 was also increased as disease progressed (Supplemental Figure 1A; supplemental material available online with this article; doi: 10.1172/JCI66580DS1). This rise in CXCL5 expression, unlike the rise in CXCL1 and CXCL2, was also evident in Apoe–/– mice fed a chow diet (CD) for 12 weeks (Figure 1, B and C), despite a lower elevation of plasma triglycerides and cholesterol levels (Supplemental Figure 1B). Of note, the level of CXCL5 induction (mRNA and protein) was similar with both diets in Apoe–/– mice, which suggests that CXCL5 expression is induced once the cholesterol levels reach a mild hypercholesterolemia but is not further increased if the cholesterol level goes above this threshold. Further analysis of the aortic arch region, which is more prone to develop atherosclerotic plaques, compared with the thoracic aortas of Apoe–/– mice fed a CD, confirmed that CXCL5, but not CXCL1 and CXCL2, expression was specifically upregulated in susceptible regions (9-fold increase) (Supplemental Figure 1C). These data suggest that the regulation of CXCL5 expression is distinct from that of CXCL1 and CXCL2 and that CXCL5 might play an essential role in atherosclerosis.

Figure 1. Upregulation of CXCL5 in atherosclerosis.

(A) Assessment of CXCL5 mRNA (blue triangles) and protein (red triangles) expression during the progression of atherosclerosis in aortas and plasma of Apoe–/– mice, respectively (n = 6–8 per time point), fed a WD for the indicated time. Apoe–/– mice fed a CD were used as controls. (B) Aortic Cxcl1, Cxcl2, and Cxcl5 mRNA and (C) plasma CXCL5 protein expression was measured in Apoe–/– mice fed CD or WD for 12 weeks (n = 8 mice per group). WT mice fed CD for 12 weeks were used as controls. (D) Assessment of Cxcl5 mRNA in aortas of WT mice (n = 6–8 per time point) fed WD. WT mice fed CD were used as controls. (E–G) HUVECs were subjected to high or low LSS and stimulated with (E) oxidized LDL (n = 3) or (F and G) IL-1β (n = 6). (E and F) CXCL8 and CXCL6 mRNA expression and (G) protein release were determined. (A–G) mRNA and protein levels were measured by qPCR and ELISA, respectively. Data are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Endothelial cells are a source of CXCL5 in atherogenic conditions.

Similar to what we observed in Apoe–/– mice, there was an increase of Cxcl5 expression in the aortas of WT animals treated with a WD (Figure 1D), a mouse model that develops mild hypercholesterolemia-induced endothelial dysfunction but without monocyte infiltration, foam macrophage accumulation, and atherosclerotic plaque formation. This intimates that CXCL5 comes from endothelial cells rather than the atheromatous plaque. Accordingly, activated macrophages and cholesterol-loaded macrophages in vitro did not produce CXCL5 (data not shown). In human endothelial cells, in which the combinatory treatment of oxidized LDL or IL-1β and proatherogenic (low) laminar shear stress (LSS) leads to a similar dysfunction, an increase of expression of the human homolog of CXCL5, CXCL6 (9), was seen compared with that in endothelial cells subjected to physiological (high) LSS (Figure 1, E–G). The expression of CXCL8, the alleged ELR+-CXCL prototype chemokine in humans, remained unchanged (Figure 1, E and F).

Inhibition of CXCL5 is associated with macrophage foam cell accumulation in atherosclerotic plaques.

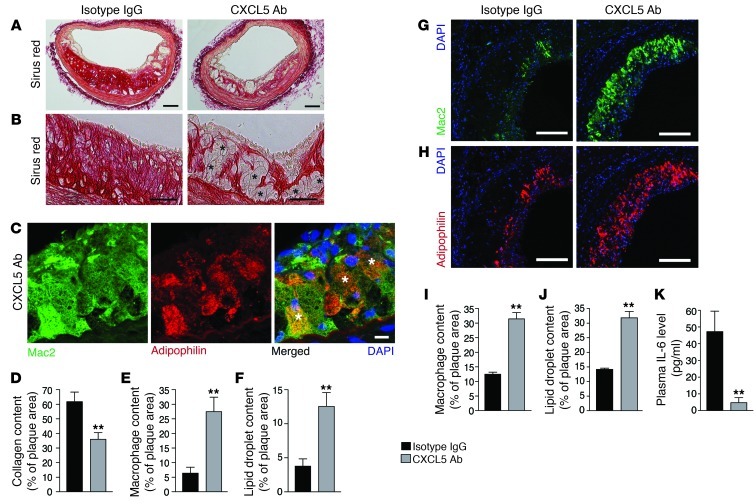

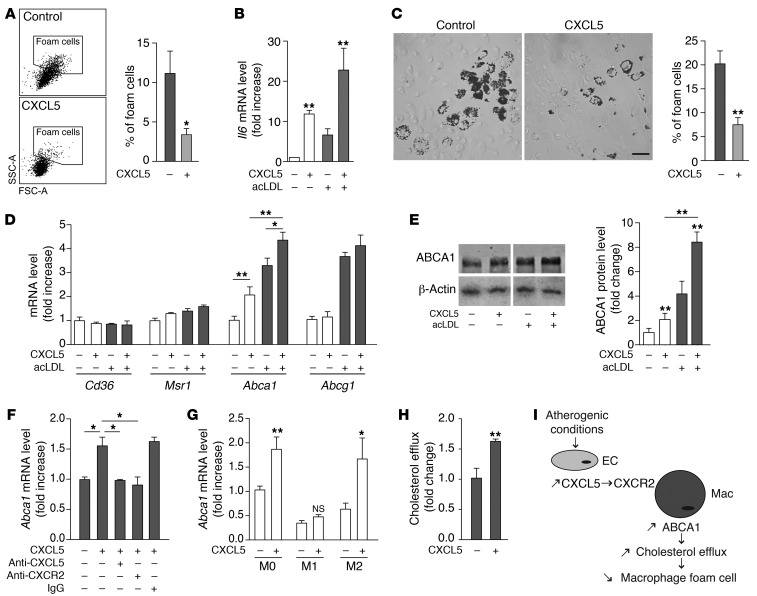

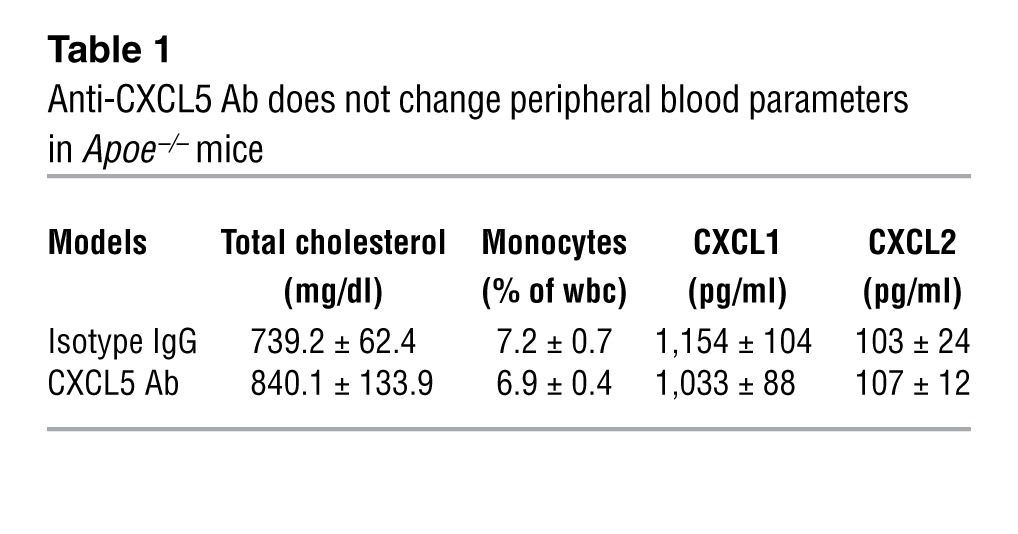

Despite the potent neutrophil chemotaxis of CXCL5 in acute inflammatory models (2, 10, 11), the rise in CXCL5 levels observed in Apoe–/– mice fed a WD was not accompanied by neutrophil infiltration within the atheromatous plaques (Supplemental Figure 1D). Moreover, blocking CXCL5 using a specific mAb did not diminish lesion size (Supplemental Figure 2, A and B) or the infiltration of monocytes/macrophages (Figure 2, E, G, and I, and Supplemental Figure 2C), as has been observed when blocking CXCL1 and CXCR2 in murine models of atherosclerosis (6, 7). Instead, we observed an accumulation of foam cells in both the brachiocephalic artery and the aortic root lesions (Figure 2B and Supplemental Figure 2E) corresponding to macrophages (Figure 2, C, E, G, and I, and Supplemental Figure 2C) with increased lipid storage capacity (Figure 2, C, F, H, and J, and Supplemental Figure 2D). This was accompanied by a significant reduction of collagen content (Figure 2, A and D, and Supplemental Figure 2, E and F), suggesting a role for CXCL5 in both macrophage activity and plaque stability. The kinin B1 receptor has been recently described to regulate CXCL5 expression (10). This specific CXCL5 reduction also could be observed in ApoE-B1R double-knockout mice (Supplemental Figure 3A) and was associated with higher macrophage foam cell accumulation in atherosclerotic plaques (Supplemental Figure 3, D–G). These observations corroborate the role of CXCL5 in atherosclerosis, without the use of blocking Abs, and in a more chronic state with mild hypercholesterolemia (after 60 weeks of CD). However, neither of the 2 models had a change in monocytosis or plasma cholesterol levels (Table 1 and Supplemental Figure 3, B and C), suggesting that CXCL5 limits macrophage foam cell accumulation through a different route. In the context of CXCL5 inhibition, it was recently described that a subsequential increase of CXCL1 and CXCL2 as well as their upstream regulator IL-17 could lead to a greater recruitment of leukocytes or leukocytosis (11, 12). Moreover, CXCL1 and CXCL2 have both been implicated in leukocyte mobilization (13, 14) and CXCL1 has been implicated as a potent monocyte chemoattractant in atherosclerosis (15). However, this indirect effect could not account for our results, since neither expression levels of CXCL1, CXCL2, and IL-17 nor monocytosis were affected here (Table 1, Supplemental Figure 3A, and Supplemental Figure 5). Importantly, we demonstrated that exogenous CXCL5 diminished peritoneal macrophage (PM) foam cell formation in vivo (Figure 3A and Supplemental Figure 4). Taken together, these findings intimate that CXCL5 can alter the phenotype of macrophages in atherosclerosis by preventing foam cell formation.

Figure 2. Blockade of CXCL5 is associated with macrophage foam cell accumulation in atherosclerotic plaques.

Apoe–/– mice were fed a WD and treated with either IgG isotype control (IgG) or anti-CXCL5 Ab (CXCL5 Ab) for 12 weeks. (A and B) Representative images from brachiocephalic artery lesions of picrosirius red staining for collagen detection. Black asterisks indicate some foam cells. (C) Representative images of macrophages (Mac2 immunostaining) containing lipid droplets (adipophilin immunostaining) from anti-CXCL5 Ab-treated brachiocephalic artery lesions. White asterisks indicate double-positive cells. (D–F) Quantification of (D) sirius red staining, (E) Mac2, and (F) adipophilin immunostaining in brachiocephalic artery lesions. Representative images from aortic root lesions of (G) Mac2 and (H) adipophilin immunostaining. Quantification of (I) Mac2 and (J) adipophilin immunostaining in aortic root lesions. (K) Quantification of plasma IL-6 by ELISA. Data in D–F and I–K represent mean ± SEM. n =7–8. **P < 0.01. Scale bars: 100 μm (A, G, and H); 50 μm (B); 10 μm (C).

Table 1.

Anti-CXCL5 Ab does not change peripheral blood parameters in Apoe–/– mice

Figure 3. CXCL5 modulates macrophage activation and induces ABCA1 expression and cholesterol efflux in macrophages.

(A) Apoe–/– mice were fed a WD and treated with CXCL5 for 12 days. By flow cytometry, PMs (CD11b+CD115+) were gated and foam cells were identified as high forward scatter (FSChi) and high side scatter (SSChi) cells. Data are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05. n = 3 animals per group. (B and D–G) BMDMs or (C and H) PMs were cholesterol loaded (gray bars) or not (white bars) with acLDL and treated with or without CXCL5 in vitro. (B) Macrophage activation was determined by Il6 mRNA expression in BMDMs using qPCR. n = 6. (C) Foam cell formation was assessed in cholesterol-loaded PMs as the percentage of Oil Red O–positive cells. Scale bar: 50 μm. n = 4. (D) Expression of genes involved in cholesterol trafficking was measured by qPCR in BMDMs. n = 6. (E) ABCA1 protein expression was measured by Western blotting in BMDMs. Lanes separated by a white line were run on the same gel but were noncontiguous. n = 3–5. (F) CXCL5-induced ABCA1 expression was blocked by anti-CXCL5 Ab and anti-CXCR2 Ab in cholesterol-loaded BMDMs. n = 4. (G) Expression of CXCL5-induced Abca1 in naive (M0), classically activated (M1), and alternatively activated (M2) macrophages from BMDM was determined by qPCR. n = 4. (H) Cholesterol efflux was assessed in cholesterol-loaded PMs treated or not with CXCL5. n = 6. (I) Proposed mechanism of action for CXCL5 in atherosclerosis. EC, endothelial cell; Mac, macrophage. Data are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

CXCL5 regulates macrophage activation.

It is well described that the T cell–adaptive response participates in atherogenesis (1). Because T cells are known to modulate macrophages, we asked whether blocking CXCL5 in atherosclerotic mice could have affected the overall profile of cytokines typically secreted by T cells. Plasma levels of cytokines produced by Th1 (IFN-γ and IL-2), Th2 (IL-4), Th17 (IL-17), or Treg (IL-10) cells were unchanged (Supplemental Figure 5). However, circulating levels of IL-6, a cytokine mainly secreted by activated macrophages, were significantly lower in Apoe–/– mice treated with anti-CXCL5 Ab (Figure 2K). In addition, a gene expression correlation analysis, based upon a microarray data set of age-dependent aorta transcriptomes from WT and Apoe–/– mice, revealed that among all cytokines only IL-6 was positively and highly correlated with CXCL5 profile expression (r = 0.76) (Supplemental Table 1). Moreover, a biological functions analysis of these correlated genes revealed that, besides the expected immune function genes, the expression of CXCL5 in atherosclerosis was particularly associated with macrophage activation genes (Supplemental Table 2, P = 1.47 × 10–7). These observations strongly suggest that CXCL5 directly acts on macrophages rather than on the T cell–adaptive response. Indeed, stimulation of primary bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) and PMs with CXCL5 induced an augmentation of Il6 expression, an effect that was even greater in cholesterol-loaded macrophages (Figure 3B and Supplemental Figure 6, B and C). Thus, in addition to the well-described neutrophil arrest and recruitment-associated functions of ELR+-CXCL chemokines, herein we demonstrate that CXCL5 specifically modulates macrophage activation, particularly by upregulating IL-6 expression.

Activation of the CXCL5/CXCR2 pathway induces ABCA1 expression and cholesterol efflux in macrophages.

Since in our experiments the primary target of CXCL5 appeared to be macrophages, we investigated whether the effects of CXCL5 on foam cell formation observed in vivo were due to a direct action. In vitro, CXCL5 was indeed able to reduce intracellular lipid accumulation in macrophages (Figure 3C). We speculated that this might be attributable to a decrease of cholesterol uptake or/and an increase of cholesterol efflux. In BMDMs and PMs, CXCL5 treatment significantly upregulated the expression of Abca1, a transporter that mediates the efflux of cholesterol (Figure 3, D and E, and Supplemental Figure 6D). In contrast, the expression of other cholesterol trafficking genes, such as Msr1, Cd36, and Abcg1, was not affected. Accordingly, in the in vivo gene expression correlation study mentioned earlier, Abca1 was highly correlated with CXCL5 expression (r = 0.78, Supplemental Table 1). ABCA1 upregulation was even more pronounced in cholesterol-loaded macrophages treated with CXCL5 (Figure 3, D and E, and Supplemental Figure 6D). Additionally, stimulation with CXCL5 induced ABCA1 expression in alternatively activated (M2) macrophages but not in classically activated (M1) macrophages (Figure 3G and Supplemental Figure 7, B and C). Accordingly, there is evidence to support that M2 macrophages are more susceptible to foam cell formation (16, 17). These observations suggest that in atherosclerotic lesions, in which macrophage heterogeneity is observed, several subtypes of macrophages can be targeted by CXCL5. Importantly, the induction of ABCA1 could be reversed, both by anti-CXCL5 Ab and by anti-CXCR2 Ab (Figure 3F, Supplemental Figure 6A, and Supplemental Figure 7C). Because IL-6 has been implicated in ABCA1 induction (18), we tested whether this was the case here. However, anti–IL-6 Ab treatment did not inhibit CXCL5-induced ABCA1 (Supplemental Figure 7A). Indeed, the fast induction of ABCA1 observed here does not support the implication of an indirect pathway through cytokine release but rather suggests that the CXCL5/CXCR2 pathway regulates ABCA1 in a direct manner. Finally, we demonstrated that CXCL5 treatment produced an increase of cholesterol efflux in macrophages (Figure 3H). Altogether these data demonstrate that CXCL5 induces ABCA1 expression and reduces the cholesterol content of macrophages.

To summarize, our findings show that, unlike other ELR+-CXCL chemokines (6, 7), the induction of CXCL5 plays a protective role in atherosclerosis (Figure 3I). It does so by limiting the cholesterol content of macrophages and therefore foam cell formation, a function that we believe has never been attributed to an ELR+-CXCL chemokine prior to this study. These findings strengthen the emerging concept that chemokines can regulate foam cell formation, as was recently proposed for CXCL4 (19). Additionally, these findings highlight the complex interplay between inflammation and atherosclerosis and support the notion that proinflammatory mediators of acute immune responses are not necessarily harmful in chronic inflammatory diseases (20, 21). This study encourages us to rethink ELR+-CXCL chemokines as important players of chronic inflammatory diseases, especially in light of their newly described role in macrophage regulation.

Methods

See Supplemental Methods for details.

Animal procedure.

All mice were males on a C57BL/6 background. 6-week-old Apoe–/– and WT mice were placed on a WD (21% fat, 0.2% cholesterol, Harlan Teklad) or remained on CD for the indicated time (see the legends for Figures 1 and 2). ELR+-CXCL chemokines were quantified from the aorta mRNA by qPCR, and plasma CXCL5 concentration was assessed by ELISA.

Additionally, Apoe–/– mice fed a WD were treated with a mouse CXCL5 mAb (50 μg per mouse, i.p., every 72 hours, R&D Systems; ref. 22) or IgG isotype control for 12 weeks. Alternatively, Apoe–/–B1R–/– and Apoe–/–B1R+/+ mice were fed a CD for 60 weeks. The brachiocephalic artery and heart were fixed with 4% PFA and embedded in paraffin for histology and immunostaining analysis. Blood was collected for measurement of leukocytes, lipids, cytokines, and chemokines.

In addition, Apoe–/– mice on WD were injected with CXCL5 (400 ng, i.p., every 72 hours, Peprotech). After 12 days, animals were sacrificed for peritoneal cell isolation. Macrophage foam cell formation was determined by flow cytometry and by staining of lipids with Oil Red O.

Cell stimulation.

Using a cone and plate viscometer, HUVECs were exposed to steady unidirectional high (10 dyn/cm2) or low (2 dyn/cm2) LSS for 24 hours. Oxidized LDL (20 μg/ml, BTI) or IL-1β (10 ng/ml, Peprotech) was added for the last 4 hours or an additional 24 hours for treatment.

PMs or BMDMs were stimulated with CXCL5 (100 ng/ml, Peprotech) and cholesterol loaded or not with acLDL (20 μg/ml, BTI). In some experiments, macrophages were also treated with CXCL5, CXCR2, IL-6, or control IgG Abs (20 μg/ml, 20 minutes prior to CXCL5 stimulation).

qPCR analysis was performed after 4 hours of treatment. ELISA and Western blotting were performed on supernatant collected at 24 to 48 hours and on cell lysate collected at 24 hours. Macrophage foam cells were stained for lipids with Oil Red O.

Statistics.

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Results were analyzed by 2-tailed Student’s t test or 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test for multiple comparisons as appropriate using GraphPad Prism software. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Study approval.

All experiments followed United Kingdom legislation for the protection of animals and were approved by the Ethical Review Process of Queen Mary, University of London.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Barts and the London Charity, European Union Seventh Framework Programme (Atherochemokine), and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (BA1374/13-2 and BA1374/16-1). J. Duchene was supported by the Marie Curie Actions (Intra-European Fellowship). We thank A. Rot (University of Birmingham, United Kingdom) for helpful discussions and A. Rigby (DRFZ, Berlin, Germany) for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Citation for this article: J Clin Invest. 2013;123(3):1343–1347. doi:10.1172/JCI66580.

References

- 1.Weber C, Zernecke A, Libby P. The multifaceted contributions of leukocyte subsets to atherosclerosis: lessons from mouse models. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(10):802–815. doi: 10.1038/nri2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viola A, Luster AD. Chemokines and their receptors: Drug targets in immunity and inflammation. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;48(1):171–197. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.121806.154841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy N, et al. Hypercholesterolaemia and circulating levels of CXC chemokines in apoE*3 Leiden mice. Atherosclerosis. 2002;163(1):69–77. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9150(01)00755-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy N. Temporal relationships between circulating levels of cc and cxc chemokines and developing atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E*3 Leiden mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(9):1615–1620. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000084636.01328.C7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tabibiazar R. Proteomic profiles of serum inflammatory markers accurately predict atherosclerosis in mice. Physiol Genomics. 2006;25(2):194–202. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00240.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boisvert WA, Santiago R, Curtiss LK, Terkeltaub RA. A leukocyte homologue of the IL-8 receptor CXCR-2 mediates the accumulation of macrophages in atherosclerotic lesions of LDL receptor-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 1998;101(2):353–363. doi: 10.1172/JCI1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boisvert WA, et al. Up-regulated expression of the CXCR2 ligand KC/GRO-α in atherosclerotic lesions plays a central role in macrophage accumulation and lesion progression. Am J Pathol. 2006;168(4):1385–1395. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.040748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chavey C, et al. CXC ligand 5 is an adipose-tissue derived factor that links obesity to insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2009;9(4):339–349. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zlotnik A, Yoshie O. The chemokine superfamily revisited. Immunity. 2012;36(5):705–716. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duchene J, et al. A novel inflammatory pathway involved in leukocyte recruitment: role for the kinin B1 receptor and the chemokine CXCL5. J Immunol. 2007;179(7):4849–4856. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mei J, et al. CXCL5 regulates chemokine scavenging and pulmonary host defense to bacterial infection. Immunity. 2010;33(1):106–117. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mei J, et al. Cxcr2 and Cxcl5 regulate the IL-17/G-CSF axis and neutrophil homeostasis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(3):974–86. doi: 10.1172/JCI60588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wengner AM, Pitchford SC, Furze RC, Rankin SM. The coordinated action of G-CSF and ELR + CXC chemokines in neutrophil mobilization during acute inflammation. Blood. 2007;111(1):42–49. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-099648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eash KJ, Greenbaum AM, Gopalan PK, Link DC. CXCR2 and CXCR4 antagonistically regulate neutrophil trafficking from murine bone marrow. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(7):2423–2431. doi: 10.1172/JCI41649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huo Y. The chemokine KC, but not monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, triggers monocyte arrest on early atherosclerotic endothelium. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(9):1307–1314. doi: 10.1172/JCI12877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oh J, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress controls M2 macrophage differentiation and foam cell formation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(15):11629–11641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.338673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yakubenko VP, Bhattacharjee A, Pluskota E, Cathcart MK. M 2 Integrin activation prevents alternative activation of human and murine macrophages and impedes foam cell formation. Circ Res. 2011;108(5):544–554. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.231803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frisdal E, et al. Interleukin-6 protects human macrophages from cellular cholesterol accumulation and attenuates the proinflammatory response. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(35):30926–30936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.264325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gleissner CA, Shaked I, Little KM, Ley K. CXC chemokine ligand 4 induces a unique transcriptome in monocyte-derived macrophages. J Immunol. 2010;184(9):4810–4818. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alexander MR, et al. Genetic inactivation of IL-1 signaling enhances atherosclerotic plaque instability and reduces outward vessel remodeling in advanced atherosclerosis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(1):70–79. doi: 10.1172/JCI43713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taleb S, et al. Loss of SOCS3 expression in T cells reveals a regulatory role for interleukin-17 in atherosclerosis. J Exp Med. 2009;206(10):2067–2077. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeyaseelan S. Induction of CXCL5 during inflammation in the rodent lung involves activation of alveolar epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32(6):531–539. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0063OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.