Abstract

Activation of the Na+-K+-2Cl−-cotransporter (NKCC2) and the Na+-Cl−-cotransporter (NCC) by vasopressin includes their phosphorylation at defined, conserved N-terminal threonine and serine residues, but the kinase pathways that mediate this action of vasopressin are not well understood. Two homologous Ste20-like kinases, SPS-related proline/alanine-rich kinase (SPAK) and oxidative stress responsive kinase (OSR1), can phosphorylate the cotransporters directly. In this process, a full-length SPAK variant and OSR1 interact with a truncated SPAK variant, which has inhibitory effects. Here, we tested whether SPAK is an essential component of the vasopressin stimulatory pathway. We administered desmopressin, a V2 receptor–specific agonist, to wild-type mice, SPAK-deficient mice, and vasopressin-deficient rats. Desmopressin induced regulatory changes in SPAK variants, but not in OSR1 to the same degree, and activated NKCC2 and NCC. Furthermore, desmopressin modulated both the full-length and truncated SPAK variants to interact with and phosphorylate NKCC2, whereas only full-length SPAK promoted the activation of NCC. In summary, these results suggest that SPAK mediates the effect of vasopressin on sodium reabsorption along the distal nephron.

The furosemide-sensitive Na+-K+-2Cl−-cotransporter (NKCC2) of the thick ascending limb (TAL) and the thiazide-sensitive Na+-Cl−-cotransporter (NCC) of the distal convoluted tubule (DCT) are key regulators of renal salt handling and therefore participate importantly in BP and extracellular fluid volume homeostasis.1 Loss-of-function mutants in the SLC12A1/ A3 genes encoding NKCC2 and NCC cause salt-losing hypotension and hypokalemic alkalosis in Bartter’s and Gitelman’s syndromes,2,3 whereas their overactivity may contribute to essential hypertension.4,5 Recently, attention has been focused on the two closely related STE20-like kinases, SPS-related proline/alanine-rich kinase (SPAK) and oxidative stress responsive kinase 1 (OSR1), which can phosphorylate NKCC2 and NCC at their N-terminal conserved threonine or serine residues (T96, T101, and T114 of mouse NKCC2 and T53, T58, and S71 of mouse NCC) and thereby activate the transporters.6–8 Despite the high homology between SPAK and OSR1 and their overlapping renal expression patterns, distinct roles along the nephron have been suggested based on data from SPAK-deficient and kidney-specific OSR1-deficient mice: deletion of SPAK primarily impairs the function of NCC, whereas deletion of OSR1 negatively affects NKCC2.9–11 The complex functional properties of a WNK-SPAK/OSR1-N(K)CC interaction cascade are currently being defined.12 Recently, arginine vasopressin (AVP), signaling via the V2 receptor (V2R), has been identified as an efficient activator of both cotransporters, affecting their luminal trafficking and phosphorylation.13–18 Because plasma AVP levels may vary not only with the sleep-wake cycle or long-term physiologic challenges, but also with pulsatile changes over the short term, distinct, time-dependent responses may occur.19 SPAK and OSR1 are well placed to regulate distal NaCl reabsorption in response to AVP. Here we tested the role of SPAK in AVP-induced activation of NKCC2 and NCC, acutely and during long-term treatment. The results suggest that SPAK is an essential kinase that modulates distal nephron function in response to AVP stimulation.

Results

Steady State Distribution of SPAK and OSR1 in Wild-Type and SPAK−/− Mice

We first characterized the abundance and distribution of SPAK and OSR1 in wild-type (WT) and SPAK−/− mice, extending previous work.9 To characterize SPAK, we first used an anti-C-terminal SPAK (C-SPAK) antibody that recognized both the full-length and the inhibitory forms.9 Immunohistochemistry with anti-C-SPAK antibody revealed strong apical signal in the TAL, whereas in the DCT, a particulate cytoplasmic signal was dominant, along with weaker subapical staining in WT (Figure 1, A, B, E, and F); the signal was absent in SPAK−/− kidneys (Figure 1, C, D, G, and H). Anti-OSR1 antibody signal was apically strong in TAL but weak in DCT of WT (Figure 1, I and J), whereas in SPAK−/−, the inverse distribution, with diminished TAL but enhanced cytoplasmic and apical DCT signals, was evident (Figure 1, K and L). These patterns, suggesting compensatory redistribution of OSR1 in SPAK deficiency, are schematized in Figure 1M.

Figure 1.

SPAK deficiency is associated with compensatory adaptation of OSR1. (A–L) SPAK and OSR1 immunostaining in TAL and DCT and double-staining with segment-specific antibodies to NKCC2 for TAL or NCC for DCT. (A–H) In WT kidneys, SPAK signal in TAL is concentrated apically (A and B). (E and F) DCT shows also cytoplasmic SPAK signal. (C, D, G, and H) Note the complete absence of SPAK signal in TAL and DCT in SPAK-deficient (SPAK−/−) kidney. (I–L) OSR1 signal is concentrated apically in TAL and DCT of WT kidneys, whereas DCT shows additional cytoplasmic signal in SPAK−/− kidneys. Note that OSR1 signal is stronger in TAL than in DCT in WT, whereas SPAK −/− shows the inverse. Bars show TAL/DCT transitions. (M) The distribution patterns of SPAK and OSR1 are schematized. Original magnification, ×400.

Steady State Phosphorylation of SPAK and OSR1 in WT and SPAK−/− Mice

Next, we studied the phosphorylation of SPAK and OSR1 within their catalytic domains (T243 in SPAK and T185 in OSR1) as an indicator of their activity.6 The antibodies directed against phosphorylated forms of SPAK and OSR1 cannot distinguish between the two, because the phosphorylation sites are similar. Staining with anti-phospho-(p)T243-SPAK/pT185-OSR1 antibody was absent in medullary TAL (mTAL) and weak in cortical TAL (cTAL) of both genotypes, whereas in DCT, moderate apical signal in WT, but weaker staining in SPAK−/− mice was observed (Figure 2, A, C, E, G, I, K, M, O, and Q). Phosphorylation of the kinases within their regulatory domains (S383 for SPAK and S325 for OSR1) may facilitate their activity as well,20 so that staining with anti-pS383-SPAK/pS325-OSR1 antibody was also performed; moderate apical TAL and apical plus cytoplasmic signal in DCT were obtained in WT (Figure 3, A, E, I, M, and Q), whereas in SPAK−/−, TAL and DCT were nearly negative (Figure 3, C, G, K, O, Q). These data are in agreement with earlier data showing that baseline phosphorylation of renal SPAK and OSR1 is low.21 They also indicate that SPAK deficiency does not elicit compensatory increase of OSR1 phosphorylation.

Figure 2.

Short-term dDAVP induces differential phosphorylation of SPAK and OSR catalytic domains; confocal microscopy. (A–P) Immunolabeling of pT243-SPAK/pT185-OSR1 (pT243/pT185) and double-staining for NKCC2 in renal medulla (A–H) and cortex (I–P) of vehicle- and dDAVP-treated (30 minutes) WT and SPAK−/− kidneys. Bars indicate TAL/DCT transitions. (Q) Signal intensities (units) obtained after confocal evaluation of pT243-SPAK/pT185-OSR1 signals in medullary (mTAL) and cortical segments (cTAL, DCT) using ZEN software. Data are the mean ± SD. *P<0.05 for intrastrain differences (vehicle versus dDAVP). Note the more pronounced response to dDAVP in WT compared with SPAK−/− mice.

Figure 3.

Short-term dDAVP induces phosphorylation of the regulatory domain of SPAK but not of OSR1; confocal microscopy. (A–P) Immunolabeling of pS383-SPAK/pS325-OSR1 (pS383/pS325) and double-staining for NKCC2 in renal medulla (A–H) and cortex (I–P) of vehicle- and dDAVP-treated (30 minutes) WT and SPAK−/− kidneys. Bars indicate TAL/DCT transitions. Note that dDAVP induces increases in both early and late DCT as identified by the absence or presence of intercalated cells (arrows). (Q) Signal intensities (units) obtained after confocal evaluation of pS383-SPAK/pS325-OSR1 signals in mTAL, cTAL, and DCT. Data are the mean ± SD. *P<0.05 for intrastrain differences (vehicle versus dDAVP). Note nearly absent pS325-OSR1 signal in SPAK−/− kidneys.

Steady State Abundance and Phosphorylation of NKCC2 and NCC upon SPAK Disruption

As reported previously,9 SPAK deficiency caused opposing baseline phosphorylation patterns of the cotransporters with NKCC2 showing enhanced pT96/pT101 signal without a difference in NKCC2 abundance, whereas NCC revealed substantially decreased pT58/pS71 signal along with decreased NCC abundance (Supplemental Figure 1).

Effects of Short-Term Desmopressin on SPAK and OSR1 Phosphorylation in WT and SPAK−/− Mice

To test whether AVP-V2R activates SPAK and/or OSR1 acutely, desmopressin (dDAVP) or vehicle were administered intraperitoneally to WT and SPAK−/− mice. Baseline endogenous AVP was slightly lower in SPAK−/− compared with WT mice (0.7 versus 1.5 ng/ml), which led us to use an established supraphysiologic dDAVP dose (1 µg/kg body weight) in order to reach saturation of AVP signaling in both genotypes.13,15 Phosphorylation of SPAK and/or OSR1 within their catalytic domains was studied with anti-pT243-SPAK/pT185-OSR1 antibody. Because immunoblotting produced unclear results, confocal evaluation was preferred. dDAVP increased pT243-SPAK/pT185-OSR1 signals in mTAL and DCT of both WT (15-fold for mTAL and 3-fold for DCT) and SPAK−/− mice (8-fold for mTAL and 2-fold for DCT), whereas significant changes were not detected in cTAL in either genotype (Figure 2). Phosphorylation of the regulatory domain was assessed with anti-pS383-SPAK/pS325-OSR1 antibody. Here, dDAVP increased the signal in mTAL and DCT of WT kidneys (1.5- and 2-fold, respectively), whereas no significant changes were recorded in SPAK−/− kidneys (Figure 3). Corresponding immunoblots showed increased signals in WT but not in SPAK−/− kidneys (Figure 4). The abundances of SPAK and OSR1 were unaffected by dDAVP (data not shown). Short-term dDAVP administration thus stimulated phosphorylation of the kinases differentially with a focus on pSPAK in mTAL and DCT.

Figure 4.

Short-term dDAVP induces phosphorylation of the regulatory domain of SPAK but not of OSR1; immunoblotting. (A–C) Representative immunoblots from WT and SPAK−/− kidneys at steady state (A) and after 30 minutes of vehicle or dDAVP treatment (B and C) show two pS383-SPAK/pS325-OSR1 (pS383/pS325)–immunoreactive bands between 50 and 75 kD in WT, whereas only the smaller product is clearly detectable in SPAK−/−. The larger product probably corresponds to pSPAK and the smaller, at least in part, to pOSR1. β-actin signals serve as the respective loading controls. (D and E) Densitometric evaluation of the immunoreactive signals normalized to loading controls shows increased signals in WT (+89% for the larger and +85% for the smaller products) but not in SPAK−/− kidneys upon dDAVP. Data are the mean ± SD. *P<0.05 for intrastrain differences.

Effects of Short-Term dDAVP on NKCC2 and NCC in WT and SPAK−/− Mice

Next, we studied the effects of dDAVP on surface expression and phosphorylation of NKCC2 and NCC. Short-term dDAVP increased the NKCC2 surface expression in both WT and SPAK−/− mice (+21% in WT and +26% SPAK−/− mice; Figure 5, A, B, E, F, and I), whereas dDAVP had no effect on NCC surface expression in either genotype (Figure 5, C, D, G, H, and J). Immunoblots of NKCC2 phosphorylation at T96/T101 revealed that dDAVP increased the abundance of pNKCC2 in WT (+55%) and more so in SPAK −/− mice (+187%). The abundance of total NKCC2 protein was concomitantly augmented in WT, but unaffected in SPAK−/− mice (Figure 6). dDAVP increased NCC phosphorylation substantially in WT (+164% for pS71-NCC and +50% for pT58-NCC), but less so in SPAK−/− mice (+53% for pS71-NCC [P<0.05] and n.s. for pT58-NCC; Figure 6). These results were confirmed and extended by confocal analysis of DCT profiles including the use of an additional anti-pT53-NCC antibody (Supplemental Figure 2). SPAK deficiency thus had no effect on dDAVP-induced trafficking of NKCC2, facilitated its phosphorylation, and attenuated NCC phosphorylation.

Figure 5.

Short-term dDAVP stimulates luminal trafficking of NKCC2 in WT and SPAK−/− but has no effect on NCC in either genotype. (A–F) Immunogold staining of NKCC2 in cortical TAL (A, B, E, and F) and NCC in DCT (C, D, G, and H) from WT and SPAK−/− mice after vehicle or dDAVP treatment (30 minutes). Transporters are distributed in the luminal plasma membrane (PM, arrows) and in cytoplasmic vesicles (arrowheads); a change is visualized for NKCC2 but not NCC (I and J). Numerical evaluations of PM NKCC2 signals (I) and NCC signals (J) per total of signals. Data are the mean ± SD. *P<0.05 for intrastrain differences.

Figure 6.

SPAK disruption facilitates short-term dDAVP-induced NKCC2 phosphorylation but attenuates NCC phosphorylation. Taking into account the dramatic differences in steady state phosphorylation of NKCC2 and NCC between genotypes, immunoblots from WT and SPAK−/− kidney extracts are run in parallel and the detection conditions are adapted to obtain a linear range for adequate signal generation. (A and B) Representative immunoblots from WT (A) and SPAK−/− kidneys (B) after 30 minutes of vehicle or dDAVP treatment showing NKCC2, pT96/pT101-NKCC2, NCC, pS71-NCC, and pT58-NCC immunoreactive bands (all approximately 160 kD). β-actin signals serve as the respective loading controls (approximately 40 kD). (C and D) Densitometric evaluation of immunoreactive signals normalized for the loading controls. Data are the mean ± SD. *P<0.05 for intrastrain differences.

Effects of Short-Term dDAVP on Interactions of SPAK and OSR1 with NKCC2 and NCC

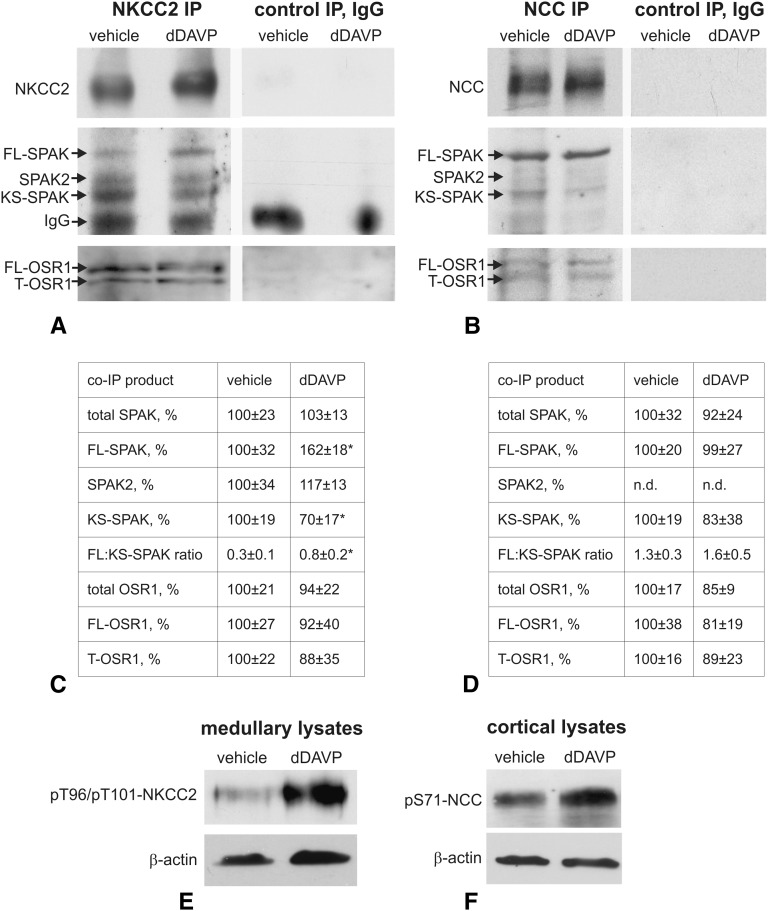

The truncated KS-SPAK isoform may limit the kinase activities of FL-SPAK or OSR1 in a dominant-negative fashion (9). Here we used Brattleboro rats with central diabetes insipidus (DI)13,15 to test whether dDAVP alters the association of activating or inhibitory SPAK and OSR1 isoforms with NKCC2 and NCC using co-immunoprecipitation assays. Presence of KS-SPAK in the rat kidney was confirmed at the RNA and protein levels (Supplemental Figure 3). At baseline, NKCC2 was chiefly bound to KS-SPAK, whereas NCC was predominantly associated with FL-SPAK. OSR1 isoforms interacted prominently with NKCC2, but less so with NCC (Figure 7, A and B). Short-term dDAVP significantly reduced binding of KS-SPAK (−30%) and increased binding of FL-SPAK to NKCC2 (+62%), whereas SPAK2 and OSR1 isoforms were not affected (Figure 7, A and C). In contrast, binding of SPAK and OSR1 isoforms to NCC was not affected by dDAVP (Figure 7, B and D). dDAVP thus specifically modulated the interaction of NKCC2 with activating and inhibiting SPAK forms.

Figure 7.

Short-term dDAVP selectively modulates interactions of SPAK variants with NKCC2 but has no effects on OSR1. (A and B) Representative immunoblots of precipitates obtained after immunoprecipitation of NKCC2 from medullary (A) or NCC from cortical kidney homogenates (B) of DI rats treated with vehicle or dDAVP (30 minutes). NKCC2-, NCC-, C-SPAK- (full-length SPAK, translationally truncated SPAK2, and kidney-specific truncated splice SPAK variant), and OSR1-immunoreactive bands (full-length and truncated OSR1 forms) are depicted. IgG bands are recognized owing to the identical host species for antibodies to NKCC2 and SPAK. Control immunoprecipitation with IgG is performed to exclude nonspecific binding of co-immunoprecipitates. (C and D) Results of densitometric quantification of single SPAK- and OSR1 isoforms normalized to NKCC2- (C) or NCC signals (D) and evaluation of FL-SPAK/KS-SPAK ratios. Data are the mean ± SD. *P<0.05 for intrastrain differences. (E and F) Effects of dDAVP stimulation were verified by parallel increases of pNKCC2 or pNCC signals in kidney extracts obtained before immunoprecipitation. IP, immunoprecipitation; FL, full-length; KS, kidney specific; T, truncated; n.d., not detectable, indicates no significant signal.

Effects of Long-Term dDAVP on Renal Function in WT and SPAK−/− Mice

We next evaluated whether SPAK is involved in the response of the distal nephron to long-term dDAVP treatment (3 days via osmotic minipumps). Physiologic effects, compared with vehicle, were more marked in WT (urine volume reduced to 25%, fraction excretion of sodium [FENa] to 23%, potassium [FEK] to 26%, and chloride [FECl] to 47%) than in SPAK−/− mice (urine volume reduced to 38%, FENa to 57%; Figure 8). NKCC2 phosphorylation was raised in WT (+87%) but not in SPAK−/−, which conversely showed an increase in NKCC2 abundance (+96%; Figure 9A). NCC abundance was raised in WT (+45%) and more so in SPAK−/− mice (+201%), and NCC phosphorylation was stimulated as well in WT (+393% for pT58-NCC and +519% for pS71-NCC) and in SPAK−/− (+475% for pT58-NCC and +355% for pS71-NCC; Figure 9A). However, due to different baseline levels among strains, values were normalized for WT vehicle levels (Figure 9). Thus, NKCC2, pNKCC2, and NCC abundances had reached similar levels in either genotype, whereas dDAVP-induced NCC phosphorylation was selectively attenuated upon SPAK disruption over the long term.

Figure 8.

SPAK disruption attenuates dDAVP-induced water and electrolyte retention at long term. (A) Water-enriched diet (food mixed with a water-containing agar) during 3 days before dDAVP or vehicle administration strongly decreases endogenous plasma AVP levels in both genotypes compared with normal AVP levels in WT mice on a regular diet. (B–E) Urine volume and FENa, FECl, and FEK are shown. The two-tailed t test is utilized to analyze the intrastrain differences between vehicle and dDAVP treatments (*P<0.05), whereas the differences in strength of dDAVP effects between WT and SPAK−/− mice are evaluated by two-way ANOVA (**P<0.05). Data are the mean ± SD. WD, water-enriched diet; RD, regular diet.

Figure 9.

SPAK disruption selectively attenuates activation of NCC upon long-term dDAVP. (A) Representative immunoblots from WT and SPAK−/− kidneys after 3 days of vehicle or dDAVP treatment showing NKCC2, pT96/pT101-NKCC2, NCC, pS71-NCC, and pT58-NCC immunoreactive bands (all approximately 160 kD). GAPDH signals serve as the respective loading controls (approximately 40 kD). (B) Densitometric evaluation of immunoreactive signals normalized to loading controls and calculation of pNCC/NCC ratios. Values obtained in WT after vehicle application are set at 100%. Data are the mean ± SD. *P<0.05 for intrastrain differences (vehicle versus dDAVP); §P<0.05 for baseline interstrain differences (WT versus SPAK−/− upon vehicle); $P<0.05 for different responses to dDAVP in WT versus SPAK−/− genotypes as analyzed by two-way ANOVA. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Effects of Long-Term dDAVP on Relative SPAK and OSR Isoform Abundances

We next studied whether dDAVP alters the relative abundance of SPAK and OSR1 products. Administration of dDAVP for 3 days significantly increased the abundances of FL-SPAK (+62%) and SPAK2 (+67%) in WT, whereas OSR1 isoforms were unaffected in either strain (Figure 10). These data were verified in DI rats receiving long-term dDAVP administration as well; resulting changes were similar to those obtained in WT mice (Supplemental Figure 4). These results suggest a prominent role for SPAK products in distal nephron adaptation at long term.

Figure 10.

Long-term dDAVP increases abundances of SPAK but not OSR1 variants. (A) Representative immunoblots showing SPAK and OSR1 immunoreactive bands in kidneys from WT and SPAK−/− mice after 3 days of vehicle or dDAVP treatment. GAPDH bands below the corresponding immunoblots serve as loading controls. (B) Densitometric evaluation of single immunoreactive bands normalized to loading controls. Values obtained in WT after vehicle application set as 100%. Data are the mean ± SD. *P<0.05 for intrastrain differences (vehicle versus dDAVP). GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; n.d., not detectable, indicates no significant signal.

Discussion

Our results add to a growing body of work documenting substantial effects of AVP on cation chloride transporters along the nephron. Here, we show that the serine/threonine kinases SPAK and OSR1 participate in that signaling mechanism. Although expressed largely by the same distal nephron segments, SPAK and OSR1 affect TAL and DCT differentially. This was illustrated earlier by the phenotype of SPAK−/− mice, which display a Gitelman-like syndrome pointing to DCT malfunction9,10; in contrast, deletion of OSR1 in the kidney caused Bartter-like syndrome, indicating TAL insufficiency.11 In SPAK−/−, we resolved a confusing phenotype of upregulated pNKCC2 in TAL and downregulated pNCC in DCT, by identifying novel SPAK isoforms with opposing actions. Whereas truncated KS-SPAK inhibited FL-SPAK- and OSR1-dependent phosphorylation of NKCC2 in TAL, FL-SPAK was critically involved in the phosphorylation of NCC in DCT.9

This study further elucidates the role of SPAK in the distal nephron and the potential of homologous OSR1 to replace its function. In spite of the known effect of OSR1 on NKCC2 function,11 SPAK disruption did not trigger any compensatory increase of its homolog in TAL. This may be related with a diminished demand for an NKCC2-activating kinase in the absence of an inhibitory one (KS-SPAK) or with parallel actions of alternative kinase pathways such as protein kinase A or AMP-activated protein kinase.8,18 In the DCT, however, the higher total OSR1 abundance may be compensatory. Because NCC abundance and phosphorylation were markedly below control levels in the SPAK-deficient mice, however, increased OSR1 is not capable of fully compensating for SPAK deficiency. The phosphorylation status of the catalytic and regulatory domains of SPAK/OSR revealed no compensatory increase of OSR1 phosphorylation in the absence of SPAK either; rather, decreased signals for the two OSR1 phosphoacceptor sites were detected in TAL and DCT. It therefore appears that SPAK is essential for NCC function, which agrees with the physiologic deficits of this model.9,10

Renal compensatory reactions are commonly triggered by endocrine stimuli.16 Surprisingly, plasma AVP and aldosterone levels were diminished in SPAK−/− mice in spite of extracellular volume depletion and a stimulated renin status.9,10 Because substantial expression of SPAK has been shown in hypothalamic brain regions and in adrenal glomerulosa cells,22–24 SPAK deletion at those sites may interfere with AVP as well as aldosterone release. AVP release itself can also affect aldosterone secretion, which may further contribute to the endocrine phenotype in SPAK−/−.25,26 In DI rats lacking AVP, reduced aldosterone levels have been observed in spite of a stimulated renin-angiotensin system as well, with the known consequences of decreased N(K)CC abundance and activity.26,27 Manifestations of SPAK deficiency such as reduced baseline phosphorylation of OSR1 and NCC may therefore be partially related with the diminished AVP and aldosterone levels.

Rapid activation of WNK1 and the SPAK/OSR1 kinases upon hypertonic or hypotonic low-chloride conditions has been reported.28,29 Here, short-term dDAVP-V2R stimulation rapidly increased the abundance of phosphorylated SPAK/OSR1 within their homologous catalytic domain. This was detected chiefly in mTAL and DCT by the recognition of a common epitope (pT243-SPAK/pT185-OSR1).4 dDAVP treatment also led to moderate increase in the abundance of phosphorylated OSR1, in the SPAK−/− animals, in which the SPAK deletion rendered the antibody specific to OSR1. The heterogenous response to AVP along the distal tubule was likely related with the distinct localization of upstream V2R signaling components such as the WNK isoforms.30 The regulatory domain (pS383-SPAK/pS325-OSR1) was activated only in WT mice, which underlines the functional heterogeneity between the kinases. Indeed, previous site-directed mutagenesis has shown that phosphorylation of SPAK at S383 facilitates its activity by abolishing an autoinhibitory action of the regulatory domain,20 whereas no such effects were described for OSR1.4

In WT, as expected from prior reports,13–17 dDAVP rapidly increased the abundance of pNKCC2 and pNCC. Interestingly, the ability of dDAVP to increase pNKCC2 abundance was not only preserved in the SPAK−/− animals, but was enhanced. Although NKCC2 phosphorylation in SPAK−/− mice may be affected predominantly by OSR1, the modest OSR1 activation under these circumstances suggests that other kinases may be involved. By contrast, the weak response of NCC to desmopressin in SPAK−/− indicates that SPAK plays a dominant role in signaling AVP to NCC in the DCT.

Acute activation of the SPAK/OSR1-substrates, NKCC2 and NCC, occurs via their apical trafficking and, independently of this translocation, by their phosphorylation at the luminal membrane.13–17 Deletion of SPAK did not affect dDAVP-induced luminal trafficking of NKCC2. Apart from the thus far unrecognized effect of OSR1, other pathways involved in NKCC2 trafficking, such as cAMP/protein kinase A signaling, may be more relevant herein.18 Surface expression of NCC was not altered by dDAVP in either mouse strain. This is in contrast to our previous report of dDAVP-induced NCC trafficking in DI rats.15 This difference, however, may have resulted from differences in experimental model; in the former study, we used DI rats, which lack any AVP at baseline. Here, WT mice, with basal AVP, were utilized.

Because KS-SPAK may limit the activities of FL-SPAK and OSR1 in a dominant-negative fashion, the interactions of SPAK/OSR1 isoforms with NKCC2 and NCC were studied in DI rats supplemented with dDAVP. In agreement with previous data on the segmental distribution of SPAK and OSR1 isoforms,9–11 the present co-immunoprecipitation experiments revealed prominent binding of KS-SPAK to NKCC2 and of FL-SPAK to NCC, whereas OSR1 strongly co-immunoprecipitated with NKCC2 but less so with NCC at baseline. Short-term dDAVP substantially modulated SPAK isoforms in their interaction with NKCC2, providing in vivo evidence that indeed, activating as well as inhibiting kinase isoforms may compete for the RFXV/I motif.9 We believe that the AVP-induced, quantitative switch between FL- and KS-SPAK isoforms bound to NKCC2 facilitates the activation of the transporter. Binding of SPAK isoforms to NCC was unaffected. Individual adjustments of FL- and KS-SPAK therefore occur selectively in TAL as previously suggested.31 Conversely, the absence of a response of OSR1 isoforms to dDAVP corroborated existing data on the heterogeneity between SPAK and OSR1.4,20 Our data thus show for the first time that interactions between SPAK isoforms and their substrates can be selectively modulated in TAL and that this can be triggered by AVP.

Long-term dDAVP decreased water and electrolyte excretion in WT and SPAK−/− mice consistent with earlier data.32 The effects of dDAVP were less pronounced in SPAK−/− mice. This difference is likely to result from the reduction in NCC abundance and phosphorylation in these animals, at baseline.9 The weaker NCC phosphorylation in SPAK−/− mice upon dDAVP supported this interpretation. It can be argued that a substitution with dDAVP for only 3 days may not have been sufficient to restore the established hypotrophy of DCT in SPAK−/− mice9; however, NCC abundance had reached WT levels upon dDAVP. An attenuation of NCC phosphorylation upon SPAK disruption must therefore be noticed. On the other hand, the effects of long-term dDAVP on NCC reveal a previously unrecognized, SPAK-independent, stimulation of NCC phosphorylation. This suggests that the increased NCC phosphorylation during chronic treatment may be an indirect response to physiologic changes, because acute dDAVP has little effect in SPAK−/− animals (see above). Given the compensatory redistribution of OSR1 in SPAK-deficient DCT and its ability to respond to AVP, we believe that OSR1 may partly mediate activation of NCC in the absence of SPAK.

The changes in kinase abundances upon long-term AVP substitution in mice and rats further confirm a clear dominance of SPAK over OSR1 in the respective nephron adaptations to AVP, which include a rise in abundance and activity of both cotransporters.27 Selective changes of SPAK but not OSR1 abundance have likewise been reported after long-term angiotensin II administration.33 Although V2R-mediated effects of AVP along TAL and DCT are well established,13–17 we cannot rule out potential interference of dDAVP with the renin-angiotensin system in our setting.25,26 Further studies are required to dissect between the direct and indirect effects of AVP in the distal nephron.

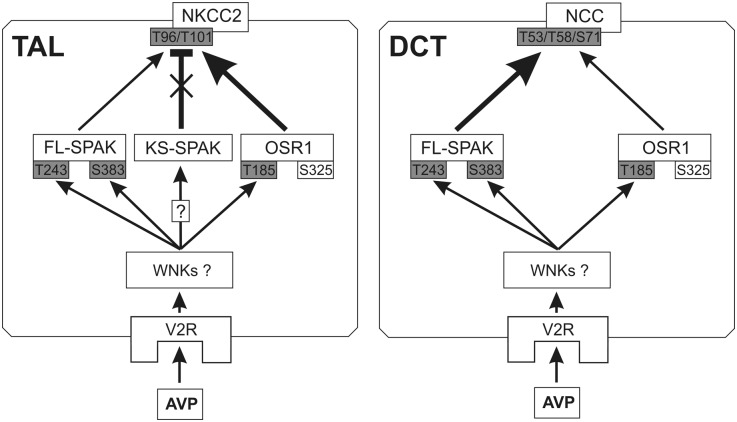

In summary, our results show an essential role for SPAK in acute AVP signaling to NCC in the DCT. Interestingly, however, compensatory processes occur during chronic V2R stimulation, which can permit AVP to stimulate NCC in a SPAK-independent manner. In contrast to the effects along DCT, SPAK deletion, which increases basal NKCC2 phosphorylation along the TAL, leads to an enhanced acute dDAVP effect on NKCC2. As shown diagrammatically in Figure 11, the dominant inhibitory KS-SPAK and the stimulatory FL-SPAK variants were modulated differentially in response to AVP to selectively bind to and control the activation of NKCC2, whereas the phosphorylation of NCC was chiefly governed by FL-SPAK. By contrast, OSR1 appeared to exert predominantly baseline functions, mainly in TAL, where its activity may be highly dependent on KS-SPAK abundance. Our data thus identify SPAK as a crucial kinase that differentially regulates Na+ reabsorption in the renal cortex and medulla under the endocrine control of AVP.

Figure 11.

Proposed model of AVP-WNK-SPAK/OSR1-NKCC2/NCC signaling in the distal nephron. Arrows indicate the downstream effects of V2R activation, and the T bar indicates inhibition. The thickness of the arrows indicates the significance of the respective kinases and their actions in AVP-induced phosphorylation of NKCC2 or NCC. Boxes shaded in gray indicate phosphoacceptor sites activated by AVP signaling. In TAL, AVP attenuates the inhibitory action of KS-SPAK (cross) and facilitates the actions of FL-SPAK and OSR1. In DCT, expression of KS-SPAK is nearly absent and FL-SPAK plays the dominant role in AVP signaling. It is presently unclear which WNK isoforms mediate AVP signaling upstream of SPAK/OSR1.

Concise Methods

Animals, Tissues, and Treatments

Adult (aged 10–12 weeks) male WT and SPAK−/− mice9 and Brattleboro rats with central DI rats (aged 10–12 weeks) were kept on standard diet and tap water. For evaluation of short-term AVP effects, mice and DI rats were divided into groups (n=8 for mice [4 mice for morphologic- and 4 mice for biochemical evaluation] and n=5 for rats [biochemical analysis only]) receiving dDAVP (1 µg/kg body weight) or vehicle (saline) for 30 minutes by intraperitoneal injection. A supraphysiologic dose was chosen in order to reach saturation of AVP signaling, because SPAK−/− had lower baseline AVP levels than WT mice (0.7 versus 1.5 ng/ml; P<0.05). Plasma AVP levels were determined using ELISA (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Burlingame, CA); to this end, blood was collected from the vena cava concomitantly with organ removal. For the long-term study of AVP, WT- and SPAK−/− mice and DI rats were divided into groups receiving 5 ng/h dDAVP or saline as vehicle (n=3 in each group of mice and n=6 in each group of rats) for 3 days via osmotic minipumps (Alzet). Rats received normal food and tap water ad libitum. Mice received a water-enriched food in order to keep endogenous AVP levels low; food was prepared as described.34 Mice received this food (21 g/animal) for 3 days before implantation of the minipumps and during treatment. After minipump implantation, mice were individually placed in metabolic cages and urine was collected during the last 24 hours of the experiment. Plasma and urine sodium, potassium, chloride, and creatinine concentrations were determined and the FE of electrolytes calculated. For morphologic evaluation, mice were anesthetized and perfusion-fixed retrogradely via the aorta using 3% paraformaldehyde.13,15 For biochemical analysis, mice and rats were sacrificed and the kidneys removed. All experiments were approved by the Berlin Senate (permission G0285/10) and Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Animal Care and Usage Committee (Protocol A858).

Immunohistochemistry

Antibodies against NKCC2,13 NCC,15 pNCC (pT53, pT58, and pS71 of mouse NCC),10,11,15 SPAK (C-terminal antibody; Cell Signaling), OSR1 (University of Dundee),4 and phosphorylated SPAK-OSR1 (pT243-SPAK/pT185-OSR1; antibody recognizes pT243 of mouse SPAK and pT185 of mouse OSR1 [T-loop; University of Dundee] and pS383-SPAK/pS325-OSR1; antibody recognizes pS383 of mouse SPAK and pS325 of mouse OSR1 [S-motif; University of Dundee])4 were applied as primary antibodies. For detection of phosphorylated kinases and transporters, the antibodies were preabsorbed with corresponding nonphosphorylated peptides in 10-fold excess before the application on kidney sections. Cryostat sections from mouse and rat kidneys were incubated with blocking medium (30 minutes), followed by primary antibody diluted in blocking medium (1 hour). For multiple staining, antibodies were sequentially applied, separated by washing step. Fluorescent Cy2-, Cy3-, or Cy5-conjugated antibodies (DIANOVA) or horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were applied for detection. Sections were evaluated in a Leica DMRB or a Zeiss confocal microscope (LSM 5 Exciter). For confocal evaluation of pSPAK/OSR1 and pNCC signal intensities, kidney sections were double-stained for NKCC2 or NCC to identify TAL and DCT, respectively. At least 20 similar tubular profiles were evaluated per individual animal. Intensities of the confocal fluorescent signals were scored across each profile using ZEN2008 software (Zeiss), and mean values within 2 µm distance at the apical side of each tubule were obtained. Background fluorescence levels were determined over cell nuclei and subtracted from the signal.

Ultrastructural Analyses

For immunogold evaluation of NKCC2 and NCC, perfusion-fixed kidneys were embedded in LR White resin. Ultrathin sections were incubated with primary antibodies to NKCC2 or NCC.13,15 Signal was detected with 10-nm nanogold-coupled secondary antibodies (Amersham) and visualized using transmission electron microscopy. Quantification of immunogold signals in TAL and DCT profiles was performed on micrographs according to an established protocol.35 Gold particles were attributed to the apical cell membrane when located near (within 20 nm of distance) or within the bilayer; particles found below 20 nm of distance to the membrane up to a depth of 2 µm or until the nuclear envelope were assigned to cytoplasmic localization. At least 10 profiles and 4–5 cells per profile were evaluated per individual animal.

Immunoblotting and Co-Immunoprecipitation

For immunoblotting, kidneys were homogenized in buffer containing 250 mM sucrose, 10 mM triethanolamine, protease inhibitors (Complete; Roche Diagnostics), and phosphatase inhibitors (Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail 1; Sigma) (pH 7.5) and nuclei removed by centrifugation (1000×g for 15 minutes). Supernatants (postnuclear homogenates) were separated in 10% polyacrylamide minigels, electrophoretically transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes, and detected using primary antibodies against NKCC2, pT96/T101-NKCC2, NCC, pT58-NCC, pS71-NCC, SPAK, pSPAK-OSR1,4,9,10,13,15 β-actin (Sigma), or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies, and chemiluminescence exposure of x-ray films. Films were evaluated densitometrically. Immunoprecipitation of NKCC2 from rat medullary kidney homogenates or NCC from rat cortical homogenates was performed overnight at 4°C in TBS/0.5% Tween using anti-NKCC2 (Millipore) or anti-NCC15 antibodies covalently bound to Dynabeads M-270 Epoxy (Invitrogen). The detergent concentration was established by testing a concentration range from 0.1% to 2% Tween. The co-immunoprecipitated products were detected by immunoblotting as described above. The specificity of the co-immunoprecipitation experiments was confirmed by IgG controls.

Cloning of Rat KS-SPAK

For identification of the alternatively spliced KS.-SPAK in rat kidney cDNA primers were designed based on alignment of rat intron 5 with mouse exon 5A sequence and two primer pares were selected from regions of aligned sequence with low homology to mouse exon 5A to reduce the possibility of amplifying mouse cDNA (forward primer 5′ CATGTGTATGCCAGATTCATCTCGAAAGAG 3′ [putative exon 5A] + reverse primer 5′ GGGCTATGTCTGGTGTTCGTGTCAGCA 3′ [exon 10], predicted PCR product size 510 bp and forward primer 5′ CCCAGGCTTTGTGGCTTTGGGTAAC 3′ [putative exon 5A] + reverse primer 5′ CAGGGGCCATCCAACATGGGG 3′ [exon 6], predicted PCR product size 363 bp). RT-PCR was performed using total RNA extracted from whole rat kidney and PCR products were cloned into pGEMT-easy vector and verified by sequencing.

Statistical Analyses

Results were evaluated using routine parametric statistics. Groups were compared by means of the t test or, if the data violated a normal distribution, the nonparametric Mann–Whitney test. The two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction was utilized to analyze the differences in effect of dDAVP between WT and SPAK−/− genotypes. A probability level of P<0.05 was accepted as significant. All results are expressed as the mean ± SD.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kerstin Riskowski, Petra Schrade, John Horn, Shaunessy Rogers, and Joshua Nelson for assistance and advice.

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (FOR667).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2012040404/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Gamba G: Molecular physiology and pathophysiology of electroneutral cation-chloride cotransporters. Physiol Rev 85: 423–493, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simon DB, Karet FE, Hamdan JM, DiPietro A, Sanjad SA, Lifton RP: Bartter’s syndrome, hypokalaemic alkalosis with hypercalciuria, is caused by mutations in the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter NKCC2. Nat Genet 13: 183–188, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simon DB, Nelson-Williams C, Bia MJ, Ellison D, Karet FE, Molina AM, Vaara I, Iwata F, Cushner HM, Koolen M, Gainza FJ, Gitleman HJ, Lifton RP: Gitelman’s variant of Bartter’s syndrome, inherited hypokalaemic alkalosis, is caused by mutations in the thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransporter. Nat Genet 12: 24–30, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vitari AC, Deak M, Morrice NA, Alessi DR: The WNK1 and WNK4 protein kinases that are mutated in Gordon’s hypertension syndrome phosphorylate and activate SPAK and OSR1 protein kinases. Biochem J 391: 17–24, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uchida S: Pathophysiological roles of WNK kinases in the kidney. Pflugers Arch 460: 695–702, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richardson C, Alessi DR: The regulation of salt transport and blood pressure by the WNK-SPAK/OSR1 signalling pathway. J Cell Sci 121: 3293–3304, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piechotta K, Lu J, Delpire E: Cation chloride cotransporters interact with the stress-related kinases Ste20-related proline-alanine-rich kinase (SPAK) and oxidative stress response 1 (OSR1). J Biol Chem 277: 50812–50819, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richardson C, Sakamoto K, de los Heros P, Deak M, Campbell DG, Prescott AR, Alessi DR: Regulation of the NKCC2 ion cotransporter by SPAK-OSR1-dependent and -independent pathways. J Cell Sci 124: 789–800, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCormick JA, Mutig K, Nelson JH, Saritas T, Hoorn EJ, Yang CL, Rogers S, Curry J, Delpire E, Bachmann S, Ellison DH: A SPAK isoform switch modulates renal salt transport and blood pressure. Cell Metab 14: 352–364, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang SS, Lo YF, Wu CC, Lin SW, Yeh CJ, Chu P, Sytwu HK, Uchida S, Sasaki S, Lin SH: SPAK-knockout mice manifest Gitelman syndrome and impaired vasoconstriction. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1868–1877, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin SH, Yu IS, Jiang ST, Lin SW, Chu P, Chen A, Sytwu HK, Sohara E, Uchida S, Sasaki S, Yang SS: Impaired phosphorylation of Na(+)-K(+)-2Cl(-) cotransporter by oxidative stress-responsive kinase-1 deficiency manifests hypotension and Bartter-like syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: 17538–17543, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCormick JA, Ellison DH: The WNKs: Atypical protein kinases with pleiotropic actions. Physiol Rev 91: 177–219, 2011. [Review] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mutig K, Paliege A, Kahl T, Jöns T, Müller-Esterl W, Bachmann S: Vasopressin V2 receptor expression along rat, mouse, and human renal epithelia with focus on TAL. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F1166–F1177, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giménez I, Forbush B: Short-term stimulation of the renal Na-K-Cl cotransporter (NKCC2) by vasopressin involves phosphorylation and membrane translocation of the protein. J Biol Chem 278: 26946–26951, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mutig K, Saritas T, Uchida S, Kahl T, Borowski T, Paliege A, Böhlick A, Bleich M, Shan Q, Bachmann S: Short-term stimulation of the thiazide-sensitive Na+-Cl- cotransporter by vasopressin involves phosphorylation and membrane translocation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F502–F509, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pedersen NB, Hofmeister MV, Rosenbaek LL, Nielsen J, Fenton RA: Vasopressin induces phosphorylation of the thiazide-sensitive sodium chloride cotransporter in the distal convoluted tubule. Kidney Int 78: 160–169, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Welker P, Böhlick A, Mutig K, Salanova M, Kahl T, Schlüter H, Blottner D, Ponce-Coria J, Gamba G, Bachmann S: Renal Na+-K+-Cl- cotransporter activity and vasopressin-induced trafficking are lipid raft-dependent. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F789–F802, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ares GR, Caceres PS, Ortiz PA: Molecular regulation of NKCC2 in the thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 301: F1143–F1159, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Vonderen IK, Wolfswinkel J, Oosterlaken-Dijksterhuis MA, Rijnberk A, Kooistra HS: Pulsatile secretion pattern of vasopressin under basal conditions, after water deprivation, and during osmotic stimulation in dogs. Domest Anim Endocrinol 27: 1–12, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gagnon KB, Delpire E: On the substrate recognition and negative regulation of SPAK, a kinase modulating Na+-K+-2Cl- cotransport activity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299: C614–C620, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rafiqi FH, Zuber AM, Glover M, Richardson C, Fleming S, Jovanović S, Jovanović A, O’Shaughnessy KM, Alessi DR: Role of the WNK-activated SPAK kinase in regulating blood pressure. EMBO Mol Med 2: 63–75, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piechotta K, Garbarini N, England R, Delpire E: Characterization of the interaction of the stress kinase SPAK with the Na+-K+-2Cl- cotransporter in the nervous system: Evidence for a scaffolding role of the kinase. J Biol Chem 278: 52848–52856, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nugent BM, Valenzuela CV, Simons TJ, McCarthy MM: Kinases SPAK and OSR1 are upregulated by estradiol and activate NKCC1 in the developing hypothalamus. J Neurosci 32: 593–598, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ushiro H, Tsutsumi T, Suzuki K, Kayahara T, Nakano K: Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel Ste20-related protein kinase enriched in neurons and transporting epithelia. Arch Biochem Biophys 355: 233–240, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazzocchi G, Malendowicz LK, Rocco S, Musajo F, Nussdorfer GG: Arginine-vasopressin release mediates the aldosterone secretagogue effect of neurotensin in rats. Neuropeptides 24: 105–108, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Möhring J, Kohrs G, Möhring B, Petri M, Homsy E, Haack D: Effects of prolonged vasopressin treatment in Brattleboro rats with diabetes insipidus. Am J Physiol 234: F106–F111, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ecelbarger CA, Kim GH, Wade JB, Knepper MA: Regulation of the abundance of renal sodium transporters and channels by vasopressin. Exp Neurol 171: 227–234, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zagórska A, Pozo-Guisado E, Boudeau J, Vitari AC, Rafiqi FH, Thastrup J, Deak M, Campbell DG, Morrice NA, Prescott AR, Alessi DR: Regulation of activity and localization of the WNK1 protein kinase by hyperosmotic stress. J Cell Biol 176: 89–100, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richardson C, Rafiqi FH, Karlsson HK, Moleleki N, Vandewalle A, Campbell DG, Morrice NA, Alessi DR: Activation of the thiazide-sensitive Na+-Cl- cotransporter by the WNK-regulated kinases SPAK and OSR1. J Cell Sci 121: 675–684, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohno M, Uchida K, Ohashi T, Nitta K, Ohta A, Chiga M, Sasaki S, Uchida S: Immunolocalization of WNK4 in mouse kidney. Histochem Cell Biol 136: 25–35, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reiche J, Theilig F, Rafiqi FH, Carlo AS, Militz D, Mutig K, Todiras M, Christensen EI, Ellison DH, Bader M, Nykjaer A, Bachmann S, Alessi D, Willnow TE: SORLA/SORL1 functionally interacts with SPAK to control renal activation of Na(+)-K(+)-Cl(-) cotransporter 2. Mol Cell Biol 30: 3027–3037, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perucca J, Bichet DG, Bardoux P, Bouby N, Bankir L: Sodium excretion in response to vasopressin and selective vasopressin receptor antagonists. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1721–1731, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Lubbe N, Lim CH, Fenton RA, Meima ME, Jan Danser AH, Zietse R, Hoorn EJ: Angiotensin II induces phosphorylation of the thiazide-sensitive sodium chloride cotransporter independent of aldosterone. Kidney Int 79: 66–76, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bouby N, Bachmann S, Bichet D, Bankir L: Effect of water intake on the progression of chronic renal failure in the 5/6 nephrectomized rat. Am J Physiol 258: F973–F979, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sandberg MB, Riquier AD, Pihakaski-Maunsbach K, McDonough AA, Maunsbach AB: ANG II provokes acute trafficking of distal tubule Na+-Cl(-) cotransporter to apical membrane. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F662–F669, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]