Abstract

Copper dyshomeostasis leading to a labile Cu2+ not bound to ceruloplasmin (“free” copper) may influence Alzheimer's disease (AD) onset or progression. To investigate this hypothesis, we investigated ATP7B, the gene that controls copper excretion through the bile and concentrations of free copper in systemic circulation. Our study analyzed informative ATP7B single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in a case–control population (n=515). In particular, we evaluated the genetic structure of the ATP7B gene using the HapMap database and carried out a genetic association investigation. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) analysis highlighted that our informative SNPs and their LD SNPs covered 96% of the ATP7B gene sequence, distinguishing two “strong LD” blocks. The first LD block contains the gene region encoding for transmembrane and copper-binding, whereas the second LD block encodes for copper-binding domains. The genetic association analysis showed significant results after multiple testing correction for all investigated variants (rs1801243, odds ratio [OR]=1.52, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.10–2.09, p=0.010; rs2147363, OR=1.58, 95% CI=1.11–2.25, p=0.010; rs1061472, OR=1.73, 95% CI=1.23–2.43, p=0.002; rs732774, OR=2.31, 95% CI=1.41–3.77, p<0.001), indicating that SNPs in transmembrane domains may have a stronger association with AD risk than variants in copper-binding domains. Our study provides novel insights that confirm the role of ATP7B as a potential genetic risk factor for AD. The analysis of ATP7B informative SNPs confirms our previous hypothesis about the absence of ATP7B in the significant loci of genome-wide association studies of AD and the genetic association study suggests that transmembrane and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) domains in the ATP7B gene may harbor variants/haplotypes associated with AD risk.

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurological disorder characterized by memory loss and progressive dementia. The late-onset form of the disease is sporadic and has a complex disease etiology, with familiarity and age as the most widely accepted risk factors. The cause of the disease appears closely related to the aggregation within the brain of the β-amyloid (Aβ) peptide and tau proteins in neurofibrillary tangles. Even though current AD research has pointed out numerous and diverse disease pathways linking the Aβ peptide and tau proteins to the disease, these proteins have not yet been completely understood. The apolipoprotein E (APOE) epsilon4 allele increases the risk and decreases the average age of onset of dementia in a dose-related fashion, and it is recognized as the major risk disease gene.1 However, it accounts for only a percentage of AD heritability, leaving several genetic risk factors to be identified.

Abnormalities in body metal balance have been proposed as additional risk factors promoting Aβprecipitation in plaques and toxicity.2,3 Specifically, it has been proposed that the hypermetallation of the Aβ peptide can be at the basis of a deranged pathway leading to redox cycles of the peptide with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) production, oligomer formation, and Aβ precipitation.2,3 A derangement of copper homeostasis leading to a labile pool may influence disease onset or progression.4,5 This notion was initially claimed in several of our studies on the basis of evidence that a specific serum pool of copper, not bound to ceruloplasmin (also named “free” copper) was associated with some typical clinical signs and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) markers of AD.4,6 Recently some investigators7 have strongly supported this notionby providing hard data demonstrating elevated levels of exchangeable Cu2+ in samples of the AD brain correlating with tissue oxidative damage.7,8 Labile copper, already reported as a marker of Wilson disease (WD)9,10—the paradigmatic disease of free copper toxicosis or intoxication—also has the potential to be a “modifying” or risk factor for AD.3,5,11

On these bases, we focused our attention on the pathway regulating copper homeostasis. Systemic copper disarrangements are present both in AD and WD patients, although metal abnormalities are less severe in AD, even though they correlated with the clinical picture.6 In WD, free copper levels are disproportionately high due to genetic defects in the adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) 7B (WD protein), which controls copper excretion through the bile and free copper levels in the general circulation.12 Molecular analysis of the ATP7B gene has revealed a number of loss-of-function (LoF) variants, which are present in WD patients but also in the general population, underlining the genetic complexity of this gene.3 Considering these aspects, we have carried out a hypothesis-driven candidate gene project exploring susceptibility loci for AD in the ATP7B gene. Our initial results seem to support this hypothesis: Two genetic studies demonstrated an association between AD and the single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) rs1061472 (c.2495 A>G, K832R) in exon 1013 and rs732774 (c.2855 G>A, R952K) in exon 12.14

To confirm the potential role of ATP7B in AD pathogenesis, we have used information about the genetic structure of ATP7B obtained through previous studies on WD genetics. In 2007, Gupta and colleagues developed a useful method to determine genotype in sibs who do not harbor the prevalent mutations of the family member with WD, based on intragenic SNP markers with high heterozygosity values in the study population.15 On the basis of this method, we screened a case–control population for informative SNPs to analyze the structure of the ATP7B gene in patients with AD and in healthy elderly controls and to identify genetic regions that may harbor susceptibility loci for AD.

Methods

Subjects

This study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board (IRB), and all participants or legal guardians signed an informed consent.

A total of 285 AD patients and 230 healthy controls were recruited by two specialized dementia care centers in Rome, Italy, The Department of Neuroscience of San Giovanni Calibita–Fatebenefratelli Hospital, and the Unit of Neurology of Campus Bio-Medico University, using the same standardized clinical protocol.16 All AD patients had been diagnosed as “probable AD” according to National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) criteria17,18 and had an Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score ≤25.19 All AD patients underwent general medical, neurologic, and psychiatric assessments. Neuroimaging diagnostic procedures (magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] or computed tomography) and complete laboratory analyses were performed to exclude other causes of progressive or reversible dementia. The control sample consisted of healthy volunteers with no clinical evidence of neurological or psychiatric disease. Exclusion criteria for both patients and controls were conditions known to affect copper metabolism and biological variables of oxidative stress (e.g., diabetes mellitus, inflammatory diseases, recent history of heart or respiratory failure, chronic liver or renal failure, malignant tumors, and a recent history of alcohol abuse).

Regarding the analysis of the rs1061472 and rs732774 genotypes, about 60% of our study population overlapped with the samples used for our previous studies. Among the study populations, 93.6% of the samples were analyzed for rs1801243, 96.9% for rs2147363, 93.2% for rs1061472 and 92.2% for rs732774, because during the analyses it was not possible to assess the genotype of some individuals (insufficient DNA/blood sample, genetic analysis failure).

SNPs genotyping

Genomic DNA was purified from peripheral blood using the conventional method for DNA isolation (QLAamp DNA Blood Midi kit). Genotyping of rs1801243, rs2147363, rs1061472, and rs732774 was performed by the TaqMan allelic discrimination assay as described in Bucossi et al.13 The predesigned SNP genotyping assay IDs are ID_C_8713998_80 (rs1801243), ID_C_25473601_10 (rs2147363), ID_C_1919004_30 (rs1061472), and ID_C_938208_30 (rs732774) (Applied Biosystems, Inc). Direct DNA bidirectional sequencing was performed for 15% of the PCR products, which were randomly selected and analyzed to confirm the genotypes. APOE genotyping was performed according to established methods.20

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics in our patient and control samples were described either in terms of mean±standard deviation (SD) if quantitative, or in terms of proportions. The Student t-test and the chi-squared test were used to compare the characteristics of AD patients and controls using the SPSS 15.0 package. Estimation of power to detect an association between ATP7B and AD was evaluated using the Power of Genetic Analysis (PGA) package.21 The minimum detectable effect with odds ratios (ORs) was calculated in a general (co-dominant) model, based on an alpha of 0.017 and AD prevalence of 1.5% in the general population. With this sample size, we had an 80% power to detect an OR of 1.52 if the risk allele frequency was higher than 25%.

Allele and genotype frequencies and Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium were evaluated using SNPStats.22 The differences in the genotype distributions among AD patients and healthy individuals were assessed by the chi-squared test. To account for multiple testing, we used the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Spectral Decomposition (SNPSpD) program to correct the significance threshold taking into account linkage disequilibrium (LD) between SNPs.23 The experiment-wide significance thresholds required to keep the type I error rate at 5% is 0.017 and at 1% is 0.003. Logistic regression was used to calculate adjusted ORs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between ATP7B SNPs and AD. Because the mode of inheritance was unknown, different genetic models were considered: Dominant (one copy of the allele is sufficient to increase the disease risk), recessive (two copies of the allele are necessary to increase the disease risk), and log-additive (r-fold increased risk for one copy of the allele, r2 increased risk for two copies of the allele). To evaluate the best model, the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) were used.

Haplotype association analysis was performed with HaploView and SNPStats. Distribution of haplotypes was compared in case and control groups with chi-squared tests in HaploView.24 Permutation tests were used to correct multiple testing errors with 100,000 simulations. Adjusted ORs and 95% CIs were computed for each haplotype and compared to the most common haplotype with SNPStats. Haplotypes with frequencies greater than 1% were considered.

To identify the functional impact of the analyzed SNPs, FASTSNP (Function Analysis and Selection Tool for SNPs) and GERP++were used.25,26

Results

We selected the set of genetic markers developed by Gupta and colleagues15 as informative SNPs to analyze the genetic structure of ATP7B. To confirm its validity for the Italian population, we performed a LD analysis in the HapMap database (available on http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) considering Tuscans in Italy (TSI), which is the HapMap population most genetically related to our study population. In Gupta and colleagues' set, four intragenic SNPs with high heterozygosity across human populations are present: rs1801243 (c.1216T>G), rs2147363 (c.1544-53 A>C), rs1061472 (c.2495 A>G), and rs732774 (c.2855 G>A). Using the HapMap LD data (HapMap Data Rel 27 PhaseII+III, Feb09, on the National Center for Biotechnology Information [NCBI] B36 assembly, dbSNP b126), we found 59 SNP in complete LD (D′=1) with at least one of Gupta and colleagues' informative SNPs in at least one HapMap population. These SNPs cover a region of 77 kb located in the ATP7B gene, which has a complete sequence of 80 kb. Moreover, two LD SNPs, rs7334118 and rs1801249, have been recorded in the Wilson Disease Mutation database (available at www.wilsondisease.med.ualberta.ca/) as disease-causing variants.

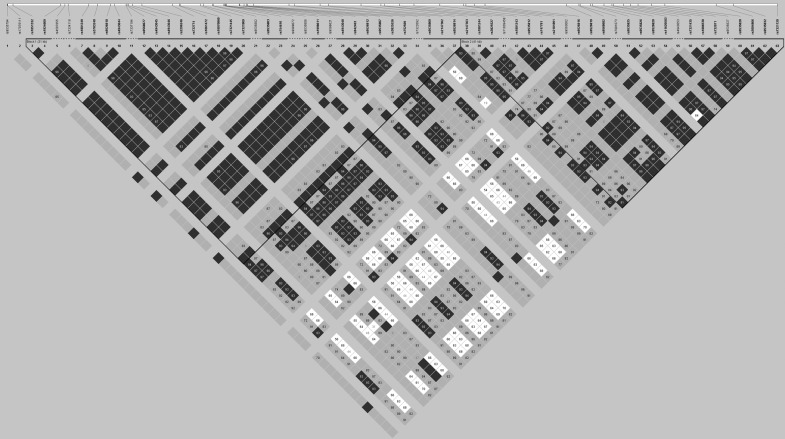

To investigate the genetic structure of ATP7B in the Italian population, an LD plot was constructed considering the HapMap data on the TSI population for 4 of Gupta and colleagues' informative SNPs and 59 LD SNPs (Fig. 1). Using the algorithm defined by Gabriel and colleagues27 to identify strong LD, two haplotype blocks were labeled: The first is from rs1051332 to rs9526814 (31 kb) and the second block is from 2147363 to rs7321120 (41 kb). Considering the Gupta and colleagues' set, rs1061472 and rs732774 are in the first block, whereas rs2147363 and rs1801243 are in the second. To simplify the subsequent description, we defined the block that spans from rs1051332 to rs9526814 as block 1 and the block that spans from 2147363 to rs7321120 as block 2.

FIG. 1.

Pairwise linkage disequilibrium (LDs) values are shown, calculated between the ATP7B SNPs in Tuscans in Italy (TSI) populations. (Top panel) Location of the variants in the ATP7B gene. The intensity of the box shading is proportional to the strength of the LD (D′) for the marker pair, which is also indicated as a percentage within each box. For boxes without any number, D′=1.

After the LD analysis, we performed the genetic association study on informative ATP7B SNPs in our case–control population, analyzing 285 AD patients and 230 healthy elderly controls. The characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. AD patients and controls did not differ in sex but did differ in age, MMSE score, and APOE E4 allele frequency. Because age and APOE genotype were considered potentially confounding factors, they were taken into account in the statistical analyses. As expected, the mean MMSE score was lower in patients than in controls. Education did not differ between the two groups, whereas the APOE E4 allele was more frequent in patients than in controls (p<0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of AD Patients and Elderly Healthy Controls

| AD patients n=285 | Controls n=230 | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 75.3 (8.0) | 67.9 (10.5) | <0.001** | |

| Sex (M/F) | 91/194 | 73/157 | 0.963 | |

| MMSE score, mean (SD) | 18.0 (5.2) | 28.4 (1.5) | <0.001** | |

| Years of education, mean (SD) | 8.9 (5.0) | 9.5 (4.6) | 0.634 | |

| APOE, E4 carriers (%) | 36.3 | 12.1 | <0.001** | |

| LD Block 2 | ATP7B rs1801243, n (%) | |||

| T/T | 55 (21) | 64 (29) | 0.041 | |

| T/G | 127 (49) | 114 (51) | ||

| G/G | 76 (30) | 46 (20) | ||

| ATP7B rs2147363, n (%) | ||||

| A/A | 17 (6) | 22 (10) | 0.025 | |

| A/C | 98 (36) | 97 (43) | ||

| C/C | 161 (58) | 104 (47) | ||

| LD Block 1 | ATP7B rs1061472, n (%) | |||

| A/A | 24 (9) | 37 (17) | 0.002** | |

| A/G | 123 (47) | 118 (53) | ||

| G/G | 113 (44) | 65 (30) | ||

| ATP7B rs732774, n (%) | ||||

| G/G | 37 (14) | 37 (17) | 0.001** | |

| G/A | 104 (41) | 119 (55) | ||

| A/A | 117 (45) | 61 (28) |

For the descriptive characteristics p<0.05 (*) and p<0.01 (**) are considered significant, whereas for ATP7B genotypes p<0.017 (*) and p<0.003 (**) are significant according multiple test correction.

AD, Alzheimer disease; SD, standard deviation; M/F, male/female; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; APOE, apolipoprotein E.

The exact test highlighted that all SNP allele frequencies were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium in both case and control groups. All genotype frequencies in our controls were within the ranges reported previously in the European origin populations of the HapMap project.

Taking into account the experiment-wide significance threshold required to keep type I error rate at 1% (α=0.003), AD patients strongly differed from healthy elderly controls in the genotype distribution of rs1061472 (p=0.002) and rs732774 (p=0.001). When adjusting for age and APOE genotypes in the logistic regression analysis, significant associations between all four ATP7B SNPs and AD were observed (Table 2). Specifically, considering the AIC and BIC scores, the best associations were: Log-additive model for rs1801243 (adjusted OR=1.52, 95% CI=1.10–2.09; p=0.010); log-additive model for rs2147363 (adjusted OR=1.58, 95% CI=1.11–2.25; p=0.010); log-additive model for rs1061472 (adjusted OR=1.73, 95% CI=1.23–2.43; p=0.002); and recessive model for rs732774 (adjusted OR=2.31, 95% CI=1.41–3.77; p<0.001).

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Analysis of Association between ATP7B SNPs and AD Risk

| rs1801243 | ||||

| Model | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted p value | AIC | BIC |

| Dominant | 1.60 (0.97–2.64) | 0.066 | 466.8 | 482.9 |

| Recessive | 1.92 (1.11–3.33) | 0.017 | 464.5 | 480.6 |

| Log-additive | 1.52 (1.10–2.09) | 0.010* | 463.6 | 479.6 |

| rs2147363 | ||||

| Model | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted p value | AIC | BIC |

| Dominant | 1.98 (0.87–4.51) | 0.110 | 464.5 | 480.6 |

| Recessive | 1.73 (1.10–2.71) | 0.017 | 461.4 | 477.4 |

| Log-additive | 1.58 (1.11–2.25) | 0.010* | 460.5 | 476.6 |

| rs1061472 | ||||

| Model | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted p value | AIC | BIC |

| Dominant | 2.00 (1.05–3.79) | 0.035 | 459.6 | 475.6 |

| Recessive | 2.03 (1.25–3.29) | 0.004* | 455.5 | 471.5 |

| Log-additive | 1.73 (1.23–2.43) | 0.002** | 453.9 | 469.9 |

| rs732774 | ||||

| Model | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted pvalue | AIC | BIC |

| Dominant | 1.07 (0.59–1.94) | 0.830 | 462.0 | 478.0 |

| Recessive | 2.31 (1.41–3.77) | <0.001** | 450.4 | 466.4 |

| Log-additive | 1.49 (1.08–2.06) | 0.015* | 456.1 | 472.1 |

The data are adjusted for age and APOE genotype. p<0.017* and p<0.003** are significant according multiple test correction.

SNPs, Single-nucleotide polymorphisms; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; AIC, Akaike Information Criterion; BIC, Bayesian Information Criterion.

After the single-locus analysis, we performed the haplotype–disease association for the ATP7B SNPs to investigate their combined effect on AD risk (Table 3). After 100,000 permutations for multiple test corrections, only the haplotype containing risk alleles at each SNP locus (GCGA) showed a statistical difference in the frequencies of case and control groups (Pm=0.031), with the GCGA haplotype being more frequent in AD patients than controls (44.3% vs. 36.3%). Given the high heterozygosity of ATP7B SNPs, the GCGA haplotype was the most common haplotype and therefore it was used as a reference in the logistic regression analysis. Nevertheless, the logistic regression model showed a significant negative association between the haplotype containing protective alleles at each locus (TAAG) and AD risk (adjusted OR=0.52, 95% CI=0.33–0.81; p=0.004).

Table 3.

Frequency and Associations between Haplotypes of ATP7B and AD Risk

| rs1801243 (T>G) | rs2147363 (A>C) | rs1061472 (A>G) | rs732774 (G>A) | AD (%) | Controls (%) | Pm | OR (95% CI) | pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | C | G | A | 44.3 | 36.3 | 0.031* | Reference | Reference |

| T | A | A | G | 18.3 | 23.5 | 0.071 | 0.52 (0.33–0.81) | 0.004* |

| T | C | G | A | 14.1 | 11.3 | 0.890 | 1.19 (0.66–2.12) | 0.570 |

| T | C | A | G | 8.5 | 9.9 | 0.996 | 0.67 (0.36–1.25) | 0.210 |

| G | C | A | G | 1.4 | 4.1 | 0.353 | 0.48 (0.12–2.01) | 0.320 |

| T | C | A | A | 2.2 | 2.7 | 1.000 | 0.81 (0.26–2.54) | 0.720 |

| G | C | G | G | 2.8 | 1.1 | 0.829 | 2.68 (0.60–12.01) | 0.200 |

| T | C | G | G | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.000 | 0.79 (0.19–3.22) | 0.740 |

| T | A | G | A | 0.9 | 2.2 | 0.979 | 0.22 (0.05–1.07) | 0.061 |

| G | A | A | G | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.000 | 0.85 (0.22–3.27) | 0.810 |

| T | A | G | G | 7.8 | 2.0 | 0.845 | 0.52 (0.08–3.41) | 0.500 |

| G | A | G | A | 1.5 | 0.9 | 1.000 | 5.02 (0.58–43.60) | 0.140 |

| G | C | A | A | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.000 | 0.60 (0.10–3.44) | 0.560 |

Type 1 error rate.

Pm values are obtained by 100,000 Permutation Multiple tests correction. ORs, 95% CI, and Pa are adjusted for age and APOE genotype. Pm <0.05* and Pa<0.017* are considered significant.

AD, Alzheimer disease; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

In the current investigation we used the same candidate gene approach previously used to identify mutations in genes encoding insulin and insulin receptors as susceptibility genes for type 2 diabetes mellitus,28 i.e., we first identified the biochemically altered pathway and then analyzed the gene regulating that pathway.3 Specifically, the choice of ATP7B as an AD genetic risk factor is based on the concept that copper toxicity by the hypermetallation of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) or by Aβ itself gives the Aβ peptide redox properties on the basis of H2O2 production and toxicity, leading to auto-oxidation and oligomer formation and eventually precipitating in plaques.2,3 Within this theoretical framework, copper homeostasis abnormality has the potential to be a risk factor able to promote or accelerate AD pathology.

To verify our copper hypothesis in the genetics of AD, we carried out a two-stage study performed on informative SNPs used in the genetics of WD. In the first, we evaluated the genetic structure of the ATP7B gene using Gupta and colleagues' informative SNPs and the HapMap database. In the second stage, we performed a genetic association study using Gupta and colleagues' informative SNPs in our case–control population.

In the LD analysis of Gupta's SNPs in HapMap populations, we individuated 59 SNPs in complete LD (D′=1), which cover 96% of the ATP7B sequence. Moreover, these genetic markers are included in two “strong LD” blocks. Gupta's SNPs are distributed in both blocks, confirming that these markers are informative for the genetic structure of ATP7B in the Italian population. Therefore, the analysis of these SNPs in the Italian population is suitable for verifying the role of ATP7B gene variation in the pathogenesis of AD and for finding the ATP7B regions that may harbor LoF variants associated with AD risk. Regarding the functional impact of Gupta's SNPs, three of the four analyzed variants are missense substitutions and two of these have an high Genomic Evolutionary Rate Profiling (GERP) score (rs732774, 6,06; rs1061472, 5.54). Considering the functions of LD SNPs, we identified three missense substitutions, 19 SNPs associated with intronic enhancers, and 37 variants with no known function. Furthermore, two of the coding LD SNPs are recorded as WD disease-causing mutations. This functional analysis confirmed that the investigated loci are not only informative for the ATP7B genetic structure but also of its functionality.

The genetic association analysis between ATP7B informative SNPs and AD risk showed significant results in both single and haplotype investigations, highlighting that rs1061472 and rs732774 have a stronger association with AD risk than do rs1801243 and rs2147363. Although the association analysis pointed out significant outcomes for all SNPs, these results seem to differentiate themselves in agreement with the LD analysis. The variants rs1801243 and rs2147363, weakly associated with AD, and rs1061472 and rs73277, highly associated with disease-risk, were located in two separate LD blocks. These differences in AD risk could be ascribed to the domains encoded by these genetic regions. Block 1, which includes rs1061472 and rs732774, covers a region of 31 kb from rs1051332 to rs9526814, where the last 17 exons (exon 5–21) are located. Specifically, these regions encode for the sixth copper binding domain (Cu6), the transmembrane domains (Tm1–7), a transduction domain (Td), the transmembrane cation channel/phosphorylation domain (ChPh), and the adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-binding domain (ATP loop). Block 2, which includes rs1801243 and rs2147363, spans a region of 41 kb from rs2147363 to rs7321120, where the first four exons (exons 1–4), encoding for five copper-binding domains (Cu 1–5), are located.

As for the analysis of the structure of the ATP7B gene, it is possible to use current knowledge of WD genetics to understand the functional differences between the two identified LD blocks in AD. To date, 526 WD mutations have been described, and the majority of them are found at very low frequency. A number of studies have investigated whether these variants are really disease-causing mutations rather than rare normal variants, highlighting that ATP7B mutations in the same protein domain can have diverse functional effects.29–32 Nevertheless, it is possible to evaluate the pathogenetic potential of our LD blocks using the Wilson Disease Mutation Database to calculate the density of disease-causing variants. In particular, we have estimated the mutation density as the number of WD mutations in the ATP7B mRNA region covered by LD blocks. In block 1, 439 disease-causing variants are present in an mRNA region of 4,779 nucleotides: 1 WD mutation every 11 nucleotides. In block 2, 69 disease-causing variants have been identified in an mRNA region of 1,492 nucleotides: One WD mutation every 22 nucleotides. Therefore, block 1 has a higher mutation density than block 2. This evidence is in agreement with some previous studies, which demonstrated that ATP7B mutation in transmembrane and ATP-binding domains (block 1) have a strong impact on protein function.33–35 It is noteworthy that rs1061472 and rs732774, strongly associated with AD in our study population, are located in transduction and transmembrane domains.

In conclusion, our investigation provides novel insights that confirm the role of ATP7B as a potential genetic risk factor for AD. In particular, we highlighted specific gene regions (block 1) that may harbor LoF variants associated with disease risk. Furthermore, we hypothesized that combinations of LoF variants, rather than a single variant, can account for the ATP7B-related risk of AD. In addition, LD analysis showed a complex genetic structure that may confirm our previous hypothesis about the absence of ATP7B in the significant loci of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of AD.3 Moreover, our outcomes on the ATP7B gene may strongly interact with the hypothesis that inorganic copper can be involved in the causation of AD.36 Individual carriers of the ATP7B disease alleles may have a higher AD susceptibility with respect to potentially toxic environmental factors, as, for example, the ingestion of inorganic copper leaching from the environment.

Finally, our study has some limitations that include the age difference between case and control groups. Adjusting data for a possible confounder is a common and reliable statistical procedure used to control in our case, the effect of age, which differed between AD and healthy cohorts. Specifically, AD patients were 7 years older on average. In a perfectly age-matched design, the age adjustment is still useful, if not necessary, but it was mandatory in our case to attempt a reduction of the age effect. However, the case–control design assumes that controls should have the possibility to “become cases,” as theorized by many epidemiologists.37 From the above, the possibility that some controls are in the condition to convert to AD while they age another 7 years makes our controls and cases closer to one other and our estimate of the association between ATP7B and AD more conservative. To confirm the data presented, further studies on a new study population are in progress. Moreover, new investigations focused on ATP7B LoF variants coupled with copper-related biochemical analyses are needed to elucidate the role of the ATP7B gene in the missing heritability of AD (in progress).

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by the following grants: Italian Health Department: “Profilo Biologico e Genetico della Disfunzione dei Metalli nella Malattia di Alzheimer e nel Mild Cognitive Impairment” (RF 2006 conv.58) to R.S.; European Community's Seventh Framework Programme Project MEGMRI (n. 200859) to P.M.R.; FISM–Fondazione Italiana Sclerosi Multipla–Cod.2010/R/38 “Fatigue Relief in Multiple Sclerosis by Neuromodulation (FaMuSNe): A transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) Intervention” to P.M.R.; Italian Ministry of Health Cod. GR-2008-1138642 “Promoting recovery from Stroke: Individually enriched therapeutic intervention in Acute phase” (ProSIA) to R.S.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Corder EH. Saunders AM. Strittmatter WJ. Schmechel DE. Gaskell PC. Small GW. Roses AD. Haines JL. Pericak-Vance MA. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer's disease in late onset families. Science. 1993;261:921–923. doi: 10.1126/science.8346443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bush AI. Tanzi RE. Therapeutics for Alzheimer's disease based on the metal hypothesis. Neurotherapeutics. 2008;5:421–432. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Squitti R. Polimanti R. Copper hypothesis in the missing hereditability of sporadic Alzheimer's disease: ATP7B gene as potential harbor of rare variants. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;29:493–501. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-111991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Squitti R. Barbati G. Rossi L. Ventriglia M. Dal Forno G. Cesaretti S. Moffa F. Caridi I. Cassetta E. Pasqualetti P. Calabrese L. Lupoi D. Rossini PM. Excess of nonceruloplasmin serum copper in AD correlates with MMSE, CSF [beta]-amyloid, and h-tau. Neurology. 2006;67:76–82. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000223343.82809.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Squitti R. Salustri C. Agents complexing copper as a therapeutic strategy for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2009;6:476–487. doi: 10.2174/156720509790147133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Squitti R. Bressi F. Pasqualetti P. Bonomini C. Ghidoni R. Binetti G. Longitudinal prognostic value of serum “free” copper in patients with Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;72:50–55. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000338568.28960.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.James SA. Volitakis I. Adlard PA. Duce JA. Masters CL. Cherny RA. Bush AI. Elevated labile Cu is associated with oxidative pathology in Alzheimer disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;52:298–302. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.10.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faller P. Copper in Alzheimer disease: Too much, too little, or misplaced? Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;52:747–748. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoogenraad T. Wilson's Disease. Intermed. Medical Publishers; Amsterdam/Rotterdam: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brewer GJ. Zinc and tetrathiomolybdate for the treatment of Wilson's disease and the potential efficacy of anticopper therapy in a wide variety of diseases. Metallomics. 2009;1:199–206. doi: 10.1039/b901614g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Squitti R. Copper dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease: From meta-analysis of biochemical studies to new insight into genetics. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorincz MT. Neurologic Wilson's disease. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2010;1184:173–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bucossi S. Mariani S. Ventriglia M. Polimanti R. Gennarelli M. Bonvicini C. Migliore S. Manfellotto D. Salustri C. Vernieri F. Rossini PM. Squitti R. Association between the c. 2495 A>G ATP7B polymorphism and sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;2011:973692. doi: 10.4061/2011/973692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bucossi S. Polimanti R. Mariani S. Ventriglia M. Bonvicini C. Migliore S. Manfellotto D. Salustri C. Vernieri F. Rossini PM. Squitti R. Association of K832R and R952K SNPs of Wilson's disease gene with Alzheimer's sisease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;29:913–919. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-111997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta A. Maulik M. Nasipuri P. Chattopadhyay I. Das SK. Gangopadhyay PK Indian Genome Variation Consortium. Ray K. Molecular diagnosis of Wilson disease using prevalent mutations and informative single-nucleotide polymorphism markers. Clin Chem. 2007;53:1601–1608. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.086066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giambattistelli F. Bucossi S. Salustri C. Panetta V. Mariani S. Siotto M. Ventriglia M. Vernieri F. Dell'acqua ML. Cassetta E. Rossini PM. Squitti R. Effects of hemochromatosis and transferrin gene mutations on iron dyshomeostasis, liver dysfunction and on the risk of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dubois B. Feldman HH. Jacova C. Dekosky ST. Barberger-Gateau P. Cummings J. Delacourte A. Galasko D. Gauthier S. Jicha G. Meguro K. O'brien J. Pasquier F. Robert P. Rossor M. Salloway S. Stern Y. Visser PJ. Scheltens P. Research criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: Revising the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:734–746. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKhann G. Drachman D. Folstein M. Katzman R. Price D. Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Folstein MF. Folstein SE. McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hixson JE. Vernier DT. Restriction isotyping of human apolipoprotein E by gene amplification and cleavage with HhaI. J Lipid Res. 2008;31:545–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menashe I. Rosenberg PS. Chen BE. PGA: Power calculator for case–control genetic association analyses. BMC Genet. 2008;9:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-9-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sole X. Guino E. Valls J. Iniesta R. Moreno V. SNPStats: A web tool for the analysis of association studies. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1928–1929. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nyholt DR. A simple correction for multiple testing for SNPs in linkage disequilibrium with each other. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:765–769. doi: 10.1086/383251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barrett JC. Fry B. Maller J. Daly MJ. Haploview: Analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuan HY. Chiou JJ. Tseng WH. Liu CH. Liu CK. Lin YJ. Wang HH. Yao A. Chen YT. Hsu CN. FASTSNP: An always up-to-date and extendable service for SNP function analysis and prioritization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W635–W641. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davydov EV. Goode DL. Sirota M. Cooper GM. Sidow A. Batzoglou S. Identifying a high fraction of the human genome to be under selective constraint using GERP++ PLoS Comput Biol. 2010;6:e1001025. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gabriel SB. Schaffner SF. Nguyen H. Moore JM. Roy J. Blumenstiel B. Higgins J. DeFelice M. Lochner A. Faggart M. Liu-Cordero SN. Rotimi C. Adeyemo A. Cooper R. Ward R. Lander ES. Daly MJ. Altshuler D. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science. 2002;296:2225–2229. doi: 10.1126/science.1069424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sudbery P. Human Molecular Genetics. 3rd. Benjamin Cummings; San Francisco: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huster D. Kühne A. Bhattacharjee A. Raines L. Jantsch V. Noe J. Schirrmeister W. Sommerer I. Sabri O. Berr F. Mössner J. Stieger B. Caca K. Lutsenko S. Diverse functional properties of Wilson disease ATP7B variants. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:947–956. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LeShane ES. Shinde U. Walker JM. Barry AN. Blackburn NJ. Ralle M. Lutsenko S. Interactions between copper-binding sites determine the redox status and conformation of the regulatory N-terminal domain of ATP7B. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:6327–6336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.074633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luoma LM. Deeb TM. Macintyre G. Cox DW. Functional analysis of mutations in the ATP loop of the Wilson disease copper transporter, ATP7B. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:569–577. doi: 10.1002/humu.21228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgan CT. Tsivkovskii R. Kosinsky YA. Efremov RG. Lutsenko S. The distinct functional properties of the nucleotide-binding domain of ATP7B, the human copper-transporting ATPase: Analysis of the Wilson disease mutations E1064A, H1069Q, R1151H, and C1104F. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:36363–36371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404553200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dmitriev O. Tsivkovskii R. Abildgaard F. Morgan CT. Markley JL. Lutsenko S. Solution structure of the N-domain of Wilson disease protein: Distinct nucleotide-binding environment and effects of disease mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5302–5307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507416103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dmitriev OY. Bhattacharjee A. Nokhrin S. Uhlemann EM. Lutsenko S. Difference in stability of the N-domain underlies distinct intracellular properties of the E1064A and H1069Q mutants of copper-transporting ATPase ATP7B. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:16355–16362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.198101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodriguez-Granillo A. Sedlak E. Wittung-Stafshede P. Stability and ATP binding of the nucleotide-binding domain of the Wilson disease protein: Effect of the common H1069Q mutation. J Mol Biol. 2008;383:1097–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brewer GJ. Copper toxicity in Alzheimer's disease: Cognitive loss from ingestion of inorganic copper. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2012;26:89–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rothman KJ. Modern Epidemiology. 1st. Little, Brown; Boston: 1986. [Google Scholar]