Abstract

Macrophages, T and B cells, and neutrophils concentrate mainly into the synovial tissue of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients and produce several inflammatory mediators including cytokines. More recently, small molecule inhibitors of signalling mediators which have intracellular targets (mainly in T and B cells) such as the Janus kinase (JAK) family of tyrosine kinases have been introduced in RA treatment. The JAK family consist of four types: JAK1, JAK2, JAK3 and TyK2. In particular, JAK3 is the only JAK family member that associates with just one cytokine receptor, the common gamma chain, which is exclusively used by the receptors for IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15 and IL-21 critically involved in T and natural killer (NK)-cell development, and B-cell function and proliferation. Tofacitinib is one of the first JAK inhibitors tested and mainly interacts with JAK1 and JAK3. Four phase II (one A and three B dose-ranging) trials in RA patients, lasting from 6 to 24 weeks, achieved significant improvements of American College of Rheumatology 20% improvement criteria (ACR20) and Disease Activity Score in 28 joints using the C-reactive protein level (DAS28-CRP) or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS-ESR; in one study that analysed this), as early as week 2 and sustained at week 24 in two studies. Doses ranged from 1, 3, 5, 10, 15, 20 up to 30 mg and were administered orally twice a day. ACR20 response rates for dosages ≥3 mg were found to be significantly (p ≤ 0.05) greater than those for placebo in all phase II studies. In general, the major adverse effects included liver test elevation, neutropenia, lipid and creatinine elevation and increased incidence of infections. More recently, RA patients randomly assigned to 5 or 10 mg of tofacitinib twice daily, in both 6- and 12-month phase III trials, achieved a significantly higher ACR20 than those receiving placebo. Adverse events occurred more frequently with tofacitinib than with placebo, and included pulmonary tuberculosis and other serious infections. The balance of efficacy and safety of tofacitinib compared with standard of care therapy is bringing this first orally available biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) a step closer for RA patients.

Keywords: biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD), Janus kinase inhibitors, kinases, rheumatoid arthritis, therapy for rheumatoid arthritis

Biological drugs targeting rheumatoid arthritis mediators

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic multifactorial immune-mediated disease with circadian clinical symptomatology. It is mainly characterized by synovial tissue proliferation and subintimal infiltration of inflammatory cells, followed by progressive and symmetrical damage of the joints [McInnes and Schett, 2011; Cutolo, 2011].

A number of different cellular responses are involved in the pathogenesis of RA, including activation of immune-inflammatory cells and expression of various cytokines and local growth factors, as well as local angiogenesis. Macrophages, T cells, B cells and neutrophils concentrate mainly into synovial tissue and produce both inflammatory and degradative mediators that break down the extracellular matrix of cartilage and bone [Emery and Dörner, 2011].

The introduction over the last decade of novel targeted therapies for RA such as biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) has facilitated considerably the approach to the ‘goal’ of disease remission much faster and safely [McInnes and O’Dell, 2010].

Biological DMARDs may interact with sensitive targets such as circulating cytokines or their receptors (i.e. tumour necrosis factor [TNF] α, interleukin [IL]-1, IL-6 and others mainly produced by macrophages), crucial surface markers of activated immune cells (i.e. CD20 on B cells) or costimulatory cell surface molecules (i.e. CD80/CD86 on antigen-presenting cells, macrophages and other cells such as osteoclasts). More recently, small molecule inhibitors of signalling mediators have been introduced which have intracellular targets (mainly T and B cells) such as the Janus kinase (JAK) family of tyrosine kinases and represent the first orally available biological DMARD [Fleischmann et al. 2012a].

Testing the right kinases as useful therapeutic targets in RA

There are 518 kinases in the human genome, divided into eight major groups. A total of 72 kinase inhibitors have been tested with 442 kinases, covering >80% of the human catalytic protein kinome [Davis et al. 2011]. Some kinase cascades have been tested in clinical trials as they play an important role in the pathogenesis of RA.

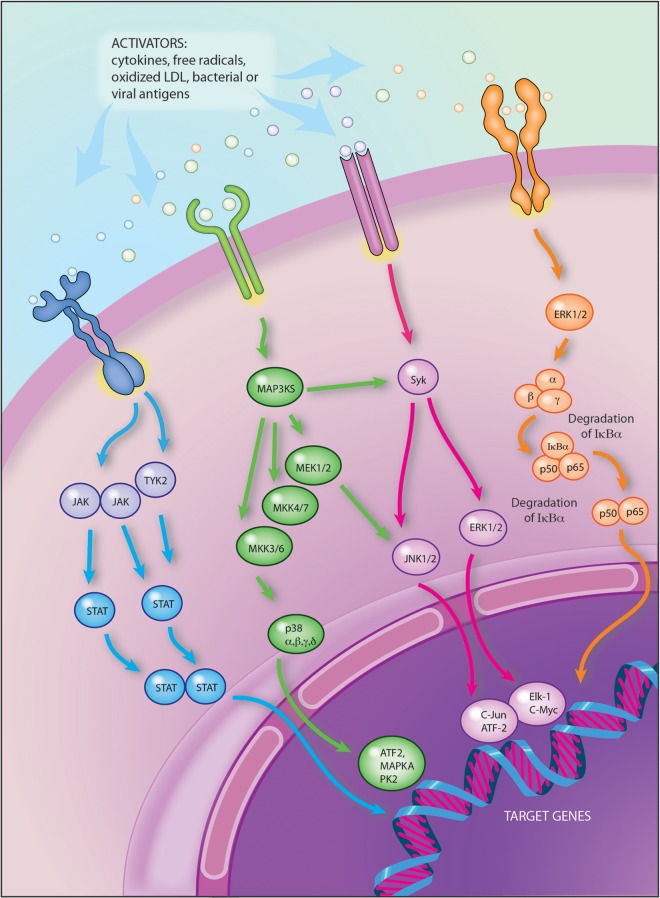

The pathway regarding the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinases (MAPK3K), once initiated by cytokine receptors, Toll-like receptors and/or other danger signals, leads to the activation of various transcription factors [Cuevas et al. 2007]. The MAPK cascade includes extracellular signal regulated kinases (ERK) and the p38 kinase (p38) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Tyrosine kinases involved in the intracellular signal transduction pathways and playing important roles in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis.

ATF2: activating transcription factor 2; c-Jun: transcription factor c-Jun; c-myc: cellular oncogene; ERK: extracellular signal-regulated kinases; ELK-1: Ets-like-protein 1 transcription factor; IkBα: subunits of IKK (also termed IKK-α); IKK: inhibitor kB kinase; JAK: Janus kinase; JNK: c-Jun N-terminal kinase; MAP3KS: mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase kinase kinase – phosphorylates and activates a MAP kinase kinase (MAPKK; e.g. MEK) and finally activation of MAP kinase (MAPK; e.g. ERK); NF-kB: nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; NIK: NFkB inducer kinase; STAT: signal transducers and activators of transcription; Syk: spleen tyrosine kinase; TYK-2: tyrosine kinase 2.

Illustration courtesy of Alessandro Baliani © [2013]. Adapted from Maurizio Cutolo’s personal slide.

The role of MAPK in transmitting signals from inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα has made the MAPKs themselves attractive targets for the development of new therapies in the treatment of RA. However, the results of clinical studies on different p38a inhibitors have been disappointing due to lack of efficacy and the presence of adverse events [Damjanov et al. 2009; Cohen et al. 2009].

In contrast, the targeting of an upstream kinase (MKK3 or MKK6) that regulates p38 could be more effective by suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines while preventing decreased IL-10 expression and increased MAPK activation [Guma et al. 2012].

Other clinical studies involved, for example, ARRY-162, an inhibitor of the MAPK extracellular signal regulated kinase (MEK). Phase I studies demonstrated that this drug was able to inhibit 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate-induced IL-1, TNFα and IL-6 production ex vivo. Phase II studies are under way in patients with RA [Trujillo, 2011].

Owing to the apparent critical role of the spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) in regulating T-cell and B-cell expansion and the proliferation of cells containing the Fcγ-activating receptor, several interventional drugs have been tested for the treatment of RA [Weinblatt et al. 2008; Genovese et al. 2011] (Figure 1). Unfortunately, although clinical efficacy in the reduction of disease activity was evident, there was high potential for adverse events including neutropenia and infections, mainly related to the specificity of some of these Syk inhibitors. Definitive results are still awaited [Winblatt et al. 2010; Scott, 2011].

Rationale behind the development of Janus kinase inhibitors in RA

To better understand the importance of JAKs as target for RA therapy, it must be recalled that a large subset of cytokines (roughly 60), which bind type I/II cytokine receptors and includes several interferons, interleukins, colony stimulating factors and other cytokines, have a shared mechanism of signal transduction [Leonard, 2001]. In particular, type I/II cytokine receptors bind JAKs, which are essential for intracell signalling and cell reactivity, even if receptors for cytokines such as IL-1 and TNFα are not themselves directly associated with kinases, but they too link to downstream kinase cascades [Pesu et al. 2005; Ghoreschi et al. 2011; Yamaoka et al. 2004].

However, the importance in vivo of JAKs was first established by the identification of patients with immunodeficiency and JAK3 mutations, as well as by knockout mice. Mutation of JAK3 results in a severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), characterized by an almost complete absence of T cells and natural killer (NK) cells, with defective B cells [Vosshenrich and Di Santo, 2002; Leonard and Lin, 2000; Buckley et al. 1997; Pesu et al. 2005].

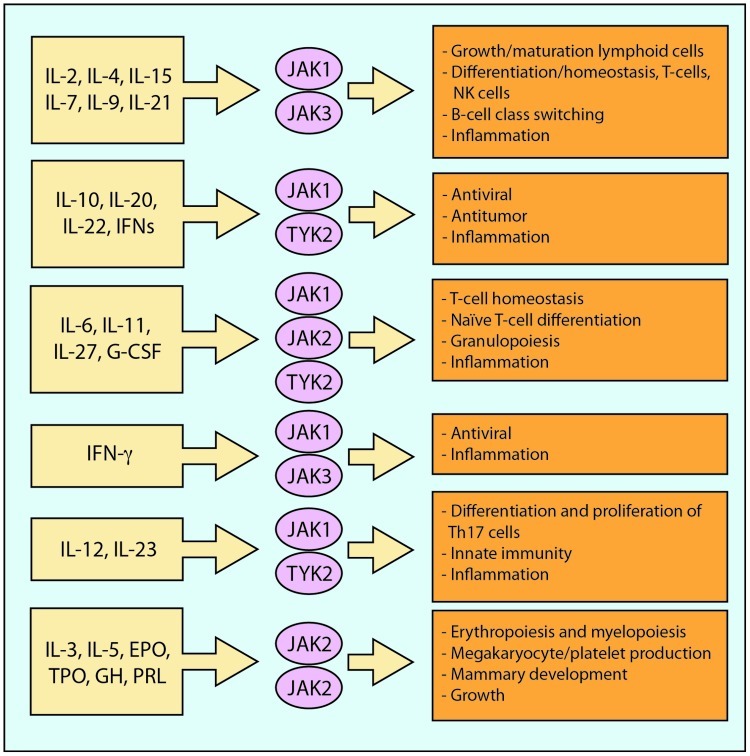

In contrast with other JAKs, JAK3 is primarily expressed in hematopoietically derived cells, where it is associated with the IL-2 receptor common gamma chain (cγc) and mediates signalling by IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15 and IL-21, cytokines which are critical for the development and maturation of T cells and of early RA pathophysiological steps [Leonard and O’Shea, 1998] (Figure 2). Thus, the selective phenotype associated with JAK3 deficiency led to the suggestion that targeting JAKs might represent a strategy for the development of a new class of immunomodulatory drugs [O’Shea et al. 2004].

Figure 2.

Biological significance of cytokine signalling through different JAK combinations.

‘Illustration courtesy of Alessandro Baliani © [2013]. Adapted from Maurizio Cutolo’s personal slide.

In general, interaction of JAKs with transmembrane cytokine activated receptors starts tyrosine phosphorylation of the receptor, with subsequent activation of STATs (signal transducer and activators of transcription) which act as transcription factors [Ghoreschi et al. 2009]. The STATs are phosphorylated by JAK, dissociate, dimerize via their SH2 domains, and translocate to the nucleus, where finally they initiate transcription of target genes [Ghoreschi et al. 2009] (Figure 1).

The JAK family consist of four types: JAK1, JAK2, JAK3 and TyK2. IL-3 and IL-5 use JAK2, whereas IL-6, IL-10, IL-11, IL-9, IL-20, IL-22 and interferon [IFN]-γ use JAK1 and JAK2. Finally, JAK3 is the only JAK family member that associates with just one cytokine receptor, the cγc, which is exclusively used by the receptors for IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15 and IL-21 [Karaman et al. 2008]. These cytokines are critically involved in T- and NK-cell development, B-cell function and proliferation [Kawamura et al. 1994] (Figure 2).

In brief, targeting selected cytokine signalling by inhibiting JAKs is a new proposed approach to downregulate the RA immune inflammatory reaction [Kawamura et al. 1994].

JAK inhibitor tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials

Tofacitinib, formerly designated CP-690,550, is one of the first intracellular JAK inhibitors to enter the clinics for the treatment of RA [Riese et al. 2010]. It has been approved by FDA to treat adults with moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis (RA) who have had an inadequate response to, or who are intolerant of, methotrexate. Tofacitinib mainly inhibits JAK3 and JAK1 and, to a lesser extent, JAK2, but has little effect on TYK2 [Riese et al. 2010]. Consequently, tofacitinib potently inhibits cγ cytokines but also blocks IFN-γ and IL-6 and, to a lesser extent, IL-12 and IL-23. Functionally, tofacitinib affects both innate and adaptive immune responses by inhibiting pathogenic Th17 cells and Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation [Ghoreschi et al. 2011].

Phase II studies

In four phase II (one A and three B dose-ranging) trials lasting from 6 to 24 weeks in RA patients, tofacitinib showed significant American College of Rheumatology 20% improvement criteria (ACR20) improvements as early as week 2 and sustained at week 24 in 2 studies.

In one early study, inclusion criteria considered RA patients who had an inadequate response to, or discontinued therapy due to unacceptable toxicity from, methotrexate, etanercept, infliximab or adalimumab [Kremer et al. 2009]. Patients also discontinued all DMARD and immunosuppressive/immunomodulatory therapy for at least 4 weeks prior to the first dose of the study drug (8 weeks for adalimumab and infliximab).

Patients (n = 264) were randomized equally to receive placebo, 5 mg, 15 mg or 30 mg of tofacitinib twice daily for 6 weeks, and were followed up for an additional 6 weeks after treatment.

By week 6, the ACR20 response rates were 70.5%, 81.2% and 76.8% in the 5 mg, 15 mg and 30 mg twice-daily groups, respectively, compared with 29.2% in the placebo group (p < 0.001) [Kremer et al. 2009]. However, the infection rate in both the 15 mg and the 30 mg twice daily groups was 30.4% (versus 26.2% in the placebo group) [Kremer et al. 2009].

In a second phase IIb dose-ranging study, tofacitinib or adalimumab monotherapy was tested versus placebo in patients with active RA with an inadequate response to DMARDs [Fleischmann et al. 2012b]. Patients could continue specified stable background RA therapy including antimalarials, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opioids (total daily dose ≤ equivalent of 30 mg of oral morphine), acetaminophen (<2.6 g/day) and/or oral corticosteroids (<10 mg prednisone or equivalent/day). Other key inclusion criteria included failure of at least one DMARD due to lack of efficacy or toxicity, and washout of all DMARDs except stable doses of antimalarials.

In this 24-week, double-blind, phase IIb study, patients with RA (n = 384) were randomized to receive placebo, tofacitinib at 1, 3, 5, 10 or 15 mg administered orally twice a day, or adalimumab at 40 mg injected subcutaneously every 2 weeks (total of 6 injections) followed by oral tofacitinib at 5 mg twice a day for 12 weeks [Fleischmann et al. 2012b].

Treatment with tofacitinib at a dose of ≥3 mg twice a day resulted in a rapid response with significant efficacy compared with placebo, as indicated by the primary end point (ACR20 response at week 12), achieved in 39.2% (3 mg; p ≤ 0.05), 59.2% (5 mg; p < 0.0001), 70.5% (10 mg; p < 0.0001) and 71.9% (15 mg; p < 0.0001) in the tofacitinib group and 35.9% of patients in the adalimumab group (p = 0.105) compared with 22.0% of patients receiving placebo. The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) in patients across all tofacitinib treatment arms (n = 272) were urinary tract infection (7.7%), diarrhoea (4.8%), headache (4.8%) and bronchitis (4.8%) [Fleischmann et al. 2012b]. In the adalimumab group (from baseline to week 12), the most common AE was a pathogen unspecified infection (3.8%). Discontinuations due to AEs occurred in 5.2% of patients. The number of patients discontinuing from this study was low overall and was comparable between all tasocitinib dose groups and placebo. The majority of the AEs were classified as mild or moderate and occurred in 5.4% (1 mg), 2.0% (5 mg), 1.6% (10 mg), 3.5% (15 mg) and 5.7% (adalimumab) of patients in the tasocitinib and adalimumab (prior to reassignment) groups.

A further phase IIb study was performed to compare the efficacy, safety and tolerability of six dosages of oral tofacitinib with placebo for the treatment of active RA in patients receiving a stable background regimen of methotrexate (MTX) who have an inadequate response to MTX monotherapy [Kremer et al. 2012]. All patients continued to receive a stable dosage of MTX. The primary end point was the ACR20 response rate at week 12.

At week 12, ACR20 response rates for patients receiving all tofacitinib dosages ≥3 mg twice daily (52.9% for 3 mg twice daily, 50.7% for 5 mg twice daily, 58.1% for 10 mg twice daily, 56.0% for 15 mg twice daily and 53.8% for 20 mg/day) were significantly (p ≤ 0.05) greater than those for placebo (33.3%) [Kremer et al. 2012]. Improvements were sustained at week 24 for the ACR20, ACR50 and ACR70 responses, scores for the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI), the three-variable Disease Activity Score in 28 joints using the C-reactive protein level (DAS28-CRP) and a three-variable DAS28-CRP of <2.6.

The most common treatment-emergent AEs occurring in >10% of patients in any tofacitinib group were diarrhoea, upper respiratory tract infection and headache; 21 patients (4.1%) experienced serious adverse events [Kremer et al. 2012].

Sporadic increases in transaminase levels, increases in cholesterol and serum creatinine levels, and decreases in neutrophil and haemoglobin levels were observed [Kremer et al. 2012].

Furthermore, in Japanese patients with active RA and inadequate response to methotrexate, the efficacy, safety and tolerability of four doses of oral tofacitinib in combination with methotrexate was compared with placebo in a phase II study [Tanaka et al. 2011]. A total of 140 patients were randomized to receive 1, 3, 5 and 10 mg of tofacitinib twice a day or placebo in this 12-week, phase II, double-blind study.

The reason for two placebo groups was that patients were randomly assigned in a 4:4:1:1 ratio to one of four regimens: tofacitinib at a dose of 5 mg twice daily for 6 months; tofacitinib at a dose of 10 mg twice daily for 6 months; placebo for 3 months followed by 5 mg of tofacitinib twice daily for 3 months; or placebo for 3 months followed by 10 mg of tofacitinib twice daily for 3 months. Comparisons with placebo for the first 3 months were performed with combined data from the two placebo groups.

ACR20 response rates at week 12 were significant (p < 0.0001) for all tofacitinib treatment groups and low disease activity was achieved by 72.7% of patients with high baseline disease activity for tofacitinib 10 mg twice a day at week 12 (p < 0.0001) [Tanaka et al. 2011]. Statistically significant improvements in the DAS28-3 (CRP) were observed at week 1 for tofacitinib 3 mg twice a day, 5 mg twice a day and 10 mg twice a day, and for all tofacitinib treatment groups at week 4; these improvements were sustained to week 12. Significant improvements were also observed in the DAS28-4 based on erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) at week 1 for tofacitinib 5 mg twice a day and 10 mg twice a day sustained to week 12, and for all tofacitinib treatment groups at week 4 sustained to week 12.

The most commonly reported AEs were nasopharyngitis (n = 13), and increased alanine aminotransferase (n = 12) and aspartate aminotransferase (n = 9) levels. These AEs were mild or moderate in severity. Serious AEs were reported by five patients: foot deformity (1 mg twice a day); osteoarthritis in the left hip (3 mg twice a day); femur fracture (5 mg twice a day); cardiac failure (10 mg twice a day); and acute dyspnoea (10 mg twice a day). Except for femur fracture, all serious AEs resolved after the patients stopped the study treatment. No serious or opportunistic infections and no deaths were reported [Tanaka et al. 2011].

Phase III studies

More recently, in a 12-month, phase III trial, 717 patients who were receiving stable doses of methotrexate were randomly assigned to 5 mg of tofacitinib twice daily, 10 mg of tofacitinib twice daily, 40 mg of adalimumab once every 2 weeks or placebo [van Vollenhoven et al. 2012].

At month 6, ACR20 response rates were higher among patients receiving 5 mg or 10 mg of tofacitinib (51.5% and 52.6%, respectively) and among those receiving adalimumab (47.2%) than among those receiving placebo (28.3%) (p < 0.001 for all comparisons) [van Vollenhoven et al. 2012]. There were also greater reductions in the HAQ-DI score at month 3 and higher percentages of patients with a DAS28-4(ESR) <2.6 at month 6 in the active treatment groups than in the placebo group. Adverse events occurred more frequently with tofacitinib than with placebo, and pulmonary tuberculosis developed in two patients in the 10-mg tofacitinib group [van Vollenhoven et al. 2012].

In conclusion, in RA patients receiving background methotrexate, tofacitinib was significantly superior to placebo and was numerically similar to adalimumab in efficacy [van Vollenhoven et al. 2012].

Finally, in a recent and intriguing phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, 6-month study, 611 RA patients were randomly assigned in a 4:4:1:1 ratio to 5 mg of tofacitinib twice daily, 10 mg of tofacitinib twice daily, placebo for three months followed by 5 mg of tofacitinib twice daily or placebo for 3 months followed by 10 mg of tofacitinib twice daily [Fleischmann et al. 2012b].

At month 3, a higher percentage of patients in the tofacitinib groups than in the placebo groups met the criteria for an ACR20 response (59.8% in the 5 mg tofacitinib group and 65.7% in the 10 mg tofacitinib group versus 26.7% in the combined placebo groups, p < 0.001 for both comparisons) [Fleischmann et al. 2012b]. The percentage of patients with a DAS28-4 (ESR) <2.6 was not significantly higher with tofacitinib than with placebo (5.6% and 8.7% in the 5 mg and 10 mg tofacitinib groups, respectively, and 4.4% with placebo; p = 0.62 and p = 0.10 for the two comparisons). However, serious infections developed in six patients who were receiving tofacitinib. Common AEs were headache and upper respiratory tract infection [Fleischmann et al. 2012].

Conclusion

Compounds that inhibit tyrosine kinase pathways involved in cellular signalling have been shown to be effective in RA treatment with an acceptable risk : benefit ratio, whereas it seems too early to report about inhibitors of other pathways [Fleischmann et al. 2012a].

The latest clinical findings regarding the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib show a significant ACR20 response versus placebo-treated RA patients. In general, the major AEs of tofacitinib include liver test elevation, neutropenia lipid and creatinine elevation and increased incidence of infections (including herpes zoster, 5%) and appear to be consequences of blocking several cytokine signals as one might expect.

Interestingly, the rate of lymphomas or other lymphoproliferative disorders in the tofacitinib RA clinical studies was 0.07 per 100 patient years (95% confidence interval, 0.03–0.15) and is consistent with the rates of lymphoma among all RA patients and among those treated with biological DMARDs [Wolfe and Michaud, 2007].

The safety of tofacitinib needs to be evaluated in a larger number of patients who have received treatment for longer periods.

In addition, its efficacy should also be monitored using other imaging techniques including joint magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound analysis.

In conclusion, the balance of efficacy and safety of tofacitinib compared with standard of care therapy seems better as ascertained by recent clinical phase III trials which bring this new oral DMARD therapy a step closer for RA patients, also as monotherapy [Leah, 2012].

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The author declares no conflict of interest in preparing this article.

References

- Buckley R., Schiff R., Schiff S., Markert M., Williams L., Harville T., et al. (1997) Human severe combined immunodeficiency: genetic, phenotypic, and functional diversity in one hundred eight infants. J Pediatr 130: 378–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Cheng T., Chindalore V., Damjanov N., Burgos-Vargas R., Delora P., et al. (2009) Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of pamapimod, a p38 MAP kinase inhibitor, in a double-blind, methotrexate-controlled study of patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 60: 335–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas B., Abell A., Johnson G. (2007) Role of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinases in signal integration. Oncogene 26: 3159–3171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutolo M. (2011) Rheumatoid arthritis: circadian and circannual rhythms in RA. Nat Rev Rheumatol 7: 500–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damjanov N., Kauffman R., Spencer-Green G. (2009) Efficacy, pharmacodynamics, and safety of VX-702, a novel p38 MAPK inhibitor, in rheumatoid arthritis: results of two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical studies. Arthritis Rheum 60: 1232–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M., Hunt J., Sanna Herrgard S., Ciceri P., Wodicka L., Pallares G., et al. (2011) Comprehensive analysis of kinase inhibitor selectivity. Nat Biotechnol 29: 1046–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery P., Dörner T. (2011) Optimising treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: a review of potential biological markers of response. Ann Rheum Dis 70: 2063–2070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann R. (2012) Novel small-molecular therapeutics for rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 24: 335–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann R., Cutolo M., Genovese M., Lee E., Kanik K., Sadis S., et al. (2012) Phase IIb dose-ranging study of the oral JAK inhibitor tofacitinib (CP-690,550) or adalimumab monotherapy versus placebo in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Arthritis Rheum 64: 617–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann R., Kremer J., Cush J., Schulze-Koops H., Connell C.A., Bradley J.D., et al. (2012) ORAL Solo Investigators. Placebo-controlled trial of tofacitinib monotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 367: 495–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese M., Kavanaugh A., Weinblatt M., Peterfy C., DiCarlo J., White M., et al. (2011) An oral Syk kinase inhibitor in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a three-month randomized, placebo-controlled, phase II study in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis that did not respond to biologic agents. Arthritis Rheum 63: 337–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoreschi K., Jesson M., Li X., Lee J., Ghosh S., Alsup J., et al. (2011) Modulation of innate and adaptive immune responses by tofacitinib (CP-690,550). J Immunol 186: 4234–4243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoreschi K., Laurence A., O’Shea J. (2009) Selectivity and therapeutic inhibition of kinases: to be or not to be? Nat Immunol 10: 356–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guma M., Hammaker D., Topolewski K., Corr M., Boyle D., Karin M., et al. (2012) Anti-inflammatory functions of the p38 pathway in mouse models of rheumatoid arthritis: advantages of targeting upstream kinases MKK3 or MKK6. Arthritis Rheum 2012. 64: 2887–2895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaman M., Herrgard S., Treiber D., Gallant P., Atteridge C., Campbell B., et al. (2008) A quantitative analysis of kinase inhibitor selectivity. Nat Biotechnol 26: 127–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura M., McVicar D., Johnston J., Blake T., Chen Y., Lal B., et al. (1994) Molecular cloning of L-JAK, a Janus family protein-tyrosine kinase expressed in natural killer cells and activated leukocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91: 6374–6378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer J., Bloom B., Breedveld F., Coombs J., Fletcher M., Gruben D., et al. (2009) The safety and efficacy of a JAK inhibitor in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase IIa trial of three dosage levels of CP-690,550 versus placebo. Arthritis Rheum 60: 1895–1905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer J., Cohen S., Wilkinson B., Connell C., French J., Gomez-Reino J., et al. (2012) A phase IIb dose-ranging study of the oral JAK inhibitor tofacitinib (CP-690,550) versus placebo in combination with background methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate alone. Arthritis Rheum 64: 970–981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leah E. (2012) Clinical trials: Phase III trial results for tofacitinib bring new oral DMARD therapy a step closer for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2012. August 28 doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.145 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard W. (2001) Role of Jak kinases and STATs in cytokine signal transduction. Int J Hematol 73: 271–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard W., Lin J. (2000) Cytokine receptor signaling pathways. J Allergy Clin Immunol 105: 877–888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard W., O’Shea J. (1998) Jaks and STATs: biological implications. Annu Rev Immunol 16: 293–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInnes I., O’Dell J. (2010) Pharmacotherapy: concepts of pathogenesis and emerging treatments. Novel therapeutics - exciting gifts but how best to use them? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 24: 441–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInnes I., Schett G. (2011) The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 365: 2205–2219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea J., Pesu M., Borie D., Changelian P. (2004) A new modality for immunosuppression: targeting the JAK/STAT pathway. Nat Rev Drug Discov 3: 555–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesu M., Candotti F., Husa M., Hofmann S., Notarangelo L., O’Shea J. (2005) Jak3, severe combined immunodeficiency, and a new class of immunosuppressive drugs. Immunol Rev 203: 127–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesu M., O’Shea J., Hennighausen L., Silvennoinen O. (2005) Identification of an acquired mutation in Jak2 provides molecular insights into the pathogenesis of myeloproliferative disorders. Mol Interv 5: 211–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riese R., Krishnaswami S., Kremer J. (2010) Inhibition of JAK kinases in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: scientific rationale and clinical outcomes. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 24: 513–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott D. (2011) Role of spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Drugs 71: 1121–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y., Suzuki M., Nakamura H., Toyoizumi S., Zwillich S. (2011) Phase II study of tofacitinib (CP-690,550) combined with methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate. Tofacitinib Study Investigators. Arthritis Care Res 63: 1150–1158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo J. (2011) MEK inhibitors: a patent review 2008–2010. Expert Opin Ther Pat 21: 1045–1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Vollenhoven R., Fleischmann R., Cohen S., Lee E., García Meijide J., Wagner S., et al. ORAL Standard Investigators (2012) Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 367: 508–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinblatt M., Kavanaugh A., Burgos-Vargas R., Dikranian A., Medrano-Ramirez G., Morales-Torres J., et al. (2008) Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with a Syk kinase inhibitor: a twelve-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 58: 3309–3318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinblatt M., Kavanaugh A., Genovese M., Peterfy C., DiCarlo J., White M., et al. (2010) An oral spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) inhibitor for rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 363: 1303–1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe F., Michaud K. (2007) Biologic treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of malignancy: analyses from a large United States observational study. Arthritis Rheum 56: 2886–2895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vosshenrich C., Di Santo J. (2002) Interleukin signaling. Curr Biol 12: R760–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaoka K., Saharinen P., Pesu M., Holt V., III, Silvennoinen O., O’Shea J., et al. (2004) The Janus kinases (JAKs). Genome Biol 5: 253–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]