Abstract

Preliminary research has demonstrated reductions in alcohol-related harm associated with increased use of protective behavioral strategies (PBS) and higher levels of drinking refusal self-efficacy (DRSE). To extend research that has evaluated these protective factors independently of one another, the present study examined the interactive effects of PBS use and DRSE in predicting alcohol outcomes. Participants were 1084 college students (63% female) who completed online surveys. Two hierarchical linear regression models revealed that both DRSE and PBS use predicted alcohol use and consequences. Additionally, DRSE moderated the relationship between PBS use and both typical weekly drinking and negative alcohol-related consequences, such that participants who reported lower levels of PBS use and DRSE in the social pressure or emotional regulation dimensions were at greatest risk for heavy drinking and consequences respectively. Interestingly, for those who reported higher levels of social and emotional DRSE, levels of PBS use had no impact on alcohol use or alcohol consequences respectively. These findings demonstrate that DRSE and PBS use differentially reduce risk, suggesting the utility of collegiate, alcohol harm reduction interventions that aim to both increase PBS use and bolster self-efficacy for greater harm reduction.

Keywords: College Student Drinking, Protective Behavioral Strategies, Drinking Refusal Self-Efficacy, Alcohol Consequences

1. Introduction

Excessive alcohol use continues to be an important concern at U.S. colleges, with 40 to 45% of students engaging in heavy episodic drinking (HED; four/five or more drinks for females/males in a two hour period; O’Malley & Johnston, 2002; Wechsler et al., 2002). Students engaging in HED are at risk for numerous consequences ranging in severity from poor academic performance to injury or death (Hingson et al., 2005; Wechsler et al., 2002). Researchers concerned with these high levels of risky drinking have begun to investigate drinking-related self-efficacy since a student’s ability to resist drinking and initiate behavioral change relies upon that individual’s perceived self-efficacy to do so (Cho, 2006).

To explore the relationship between self-efficacy and alcohol outcomes, Young, Oei, and Crook (1991) introduced the concept of drinking refusal self-efficacy (DRSE). DRSE refers to individuals’ perceptions of their ability to resist alcohol in three dimensions: drinking involving social pressure (e.g. when at a party), drinking directed towards emotional relief (e.g. when anxious/stressed/worried), and drinking when provided an opportunity to do so (e.g. when offered a drink; Lee & Oei, 1993; Young et al., 1991). Several studies have explored the influence of overall DRSE, a composite of the three dimensions, and the differential impact of each dimension individually. Among college students, lower overall DRSE is related to both intentions to drink and greater alcohol consumption (Baldwin, Oei, & Young, 1993; Collins, Witkiewitz, & Larimer, 2011), and early research evaluating the individual dimensions of DRSE demonstrates that students lower in social DRSE and opportunistic DRSE typically consume more alcohol (Young et al., 1991). Further, overall DRSE contributes unique variance to the prediction of alcohol consumption in college students when controlling for positive and negative alcohol expectancies, two well-known predictors of use (Oei & Jardim, 2007; Young, Conner, Ricciardelli, & Saunders, 2006). Recent research additionally indicates that DRSE is a strong, proximal predictor of risky drinking, mediating the effects of impulsivity, alcohol expectancies, and sensitivity to reward to hazardous alcohol use (Gullo, Dawe, Kambouropoulos, Stalger, & Jackson, 2010). As a result of the recent research demonstrating the significant role of DRSE on alcohol-related outcomes, researchers have suggested the inclusion of DRSE into collegiate alcohol-related harm reduction efforts (Cho, 2006; Collins, Witkiewitz, & Larimer, 2011).

Current intervention and prevention programs targeting risky drinking among collegiate populations often include alcohol information, social norms reeducation, personalized feedback, and motivational enhancement components (Borsari, Murphy, & Carey, 2009; Carey, Scott- Sheldon, Carey, & DeMartini, 2007; Larimer & Cronce, 2007; Perkins, 2002; Wechsler, Kelley, Weitzman, San Giovanni, & Seibring, 2000; Wechsler et al., 2003). In addition, intervention researchers are increasingly investigating the inclusion of protective behavioral strategies (PBS; e.g., Martens et al., 2005; Sugarman & Carey, 2009) to slow the speed of or modify the manner of drinking (e.g., wait 15 min between drinks; avoid drinking games), limit the amount of alcohol consumed (e.g., alternate nonalcoholic with alcoholic drinks; determine not to exceed a set number of drinks), and prevent the serious negative consequences that might occur as a result of heavy drinking (e.g., take a taxi instead of driving while intoxicated; know where your drink has been at all times). An increasing body of evidence indicates that greater PBS use is associated with lower levels of consumption and fewer drinking-related problems among college students (Araas & Adams, 2008; Delva et al., 2004; LaBrie, Kenney, Lac, Garcia, & Ferraiolo, 2009; Martens et al., 2004; Martens, Pedersen, LaBrie, Ferrier, & Cimini, 2007; Sugarman & Carey, 2007).

Although significant evidence supports the benefit of PBS use and higher levels of DRSE independently in reducing both alcohol consumption and related consequences, no research to our knowledge has simultaneously explored PBS use and DRSE. The interactive effects of PBS and DRSE may reveal important insights into high-risk groups among college students, as well as offer potential for alcohol harm reduction intervention planning. For example, use of concrete and easy-to-use PBS in drinking situations may provide students with DRSE deficits a mechanism to moderate their levels of alcohol consumption and reduce their risk for alcohol-related harm. Hence, a primary aim of this study was to investigate how the belief regarding one’s own self-efficacy in refusing drinks (i.e., DRSE) interacts with use of protective behaviors while drinking (i.e., PBS) to impact alcohol consumption and negative consequences. Since only one study has examined differential impacts of the three different components of DRSE (i.e., social pressure, emotional relief, opportunistic drinking) on alcohol outcomes, this study utilized these three DRSE dimensions to expand the understanding of how different dimensions of DRSE impact alcohol-related outcomes. It was hypothesized that higher levels of each DRSE dimension would be related to lower levels of alcohol consumption and associated consequences. Similarly, greater PBS use was hypothesized to be associated with lower levels of drinking and consequences. Finally, it was hypothesized that DRSE dimensions would moderate the impact of PBS use on drinking outcomes, such that higher levels of each DRSE dimension and PBS use would combine to be associated with the lowest levels of alcohol use and related consequences. Conversely, lower levels of each DRSE dimension and PBS use would be associated with the highest levels of drinking and consequences.

2. Method

2.1 Participants and Procedure

Participants were undergraduate students from two west-coast universities—one a large public university with an enrollment of approximately 30,000 students, and the other a medium-sized private university with an enrollment of about 6,000 students. In the Fall of 2010, with the assistance of the Registrar’s Offices at both universities, a randomly selected sample of 5998 students, stratified across class year and equally portioned from both universities, was invited to participate in a research study examining alcohol use and related attitudes among college students. Invitations were sent via mail and email, and included a designated URL which directed students to an IRB-approved online consent form, completion of which enabled participants to access the online screening survey. Of the invited students, 2,689 (44.8%) completed the screening survey. All screening survey completers who met inclusion criteria of engaging in HED within the past month (n = 1,493; 55.5%) were similarly invited to a subsequent baseline survey. Of those invited, 1,084 (72.6%) completed the baseline survey, from which data for the current study were drawn. Participants were offered a nominal monetary incentive for completion of each survey. Recruitment rates were comparable to other large-scale studies among this population (e.g., Marlatt et al., 1998; McCabe, Boyd, Couper, Crawford, & D’Arcy, 2002; Neighbors, Lee, Lewis, Fossos, & Larimer, 2007). Participants reported a mean age of 20.1 years (SD = 1.37). A total of 63% of the sample was female, and 30% reported Greek affiliation (i.e., membership in a fraternity or sorority). Ethnic representation was as follows: 67.1% Caucasian, 13.6% Asian, 11.6% Multi-Racial, 2.9% other, 2.3% African American, 2.0% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and 0.5% Native American.

2.2 Measures

2.3.1 Alcoholic drinks per week

The Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985; Dimeff et al., 1999) measured the number of weekly drinks consumed. Participants were asked to consider a typical week within the past month when answering, “How many drinks did you typically consume on a Monday? Tuesday?” and so on. A ‘typical weekly drinks’ variable was computed using these responses. The DDQ has been used in numerous studies of college student drinking and has demonstrated good convergent validity and test-retest reliability (Marlatt et al., 1998; Neighbors et al., 2006).

2.3.2 Alcohol consequences

The Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index (RAPI; White & Labouvie, 1989) measured negative consequences resulting from alcohol use that participants encountered within the past three months such as “Went to work or school high or drunk” and “Had withdrawal symptoms…”. Using a 5-point scale (0 = Never to 4 = 10 or more times), respondents reported past three month frequency of experiencing a problematic drinking outcome from a list of 25 items. Two additional items regarding driving while under the influence (i.e., driving after consuming 2 + drinks; driving after consuming 4+ drinks) were added to the original 23 scale items. Responses were summed to yield a ‘past three month consequences’ variable. The RAPI showed good inter-item reliability (α = .92).

2.3.3 Protective behavioral strategies

Participants’ frequency of PBS use in drinking contexts was assessed using the 15-item Protective Behavioral Strategies Scale (PBSS), a psychometrically validated measurement of alcohol protective behavior (Martens et al., 2005; Martens et al., 2007; Martens, Ferrier, & Cimini, 2007). The measure is comprised of statements including, “leave bar/party at a predetermined time,” “put extra ice in your drink,” “drink slowly, rather than gulp or chug,” “avoid drinking games,” and “use a designated driver.” The use of each PBS was measured on a scale of 1 (never) to 5 (always). Responses were summed to form a global ‘PBS use’ variable. The PBSS showed good inter-item reliability (α = .83).

2.3.4 Drinking Refusal Self-Efficacy

The Drinking Refusal Self-Efficacy Questionnaire Revised Adolescent Version (DRSEQ-R; Young, Oei, & Crook, 1991) measured participants’ evaluations of their self-efficacy in refusing alcoholic beverages. Participants were instructed to respond to each of 19 items by considering how sure they were that they could resist drinking alcohol in that particular context. Responses were ranked on a scale of 1 (I am very sure I could NOT resist drinking) to 6 (I am very sure I could resist drinking). The DRSEQ-R items correspond to three subscales: social pressure drinking refusal self-efficacy (social DRSE; α = .91; e.g., When someone offers me a drink), emotional relief drinking refusal self-efficacy (emotional DRSE; α = .96; e.g., When I feel frustrated), and opportunistic drinking refusal self-efficacy (opportunistic DRSE; α = .92; e.g., When I first arrive home).

2.3.5 Drinking Motives Questionnaire

The Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised (DMQ-R; Cooper, 1994) measured participants’ motives for drinking on four subscales: coping (α = .88), conformity (α = .91), social (α = .89), and enhancement (α = .88). Participants reported how often they drank for a given motivation (e.g., to be sociable, to forget your worries) on a scale of 1 (almost never/never) to 5 (almost always/always).

2.4 Analytic Plan

To reduce the probability for Type-I error due to the number of statistical comparisons, a more stringent alpha level of .01 was utilized for all analyses. First, bivariate associations were examined via correlation analyses, and independent t tests were conducted to examine mean differences by gender (Table 1). In addition, two separate hierarchical multiple regression models were used to examine alcohol consumption and alcohol consequences.

Table 1.

Correlation Matrix and Means by Gender for All Study Variables

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | Males

|

Females

|

t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||||||||

| 1. PBS | — | .34** | .21** | .14** | −.27** | −.35** | 54.09 (10.06) | 60.16 (10.68) | 9.47*** |

| 2. DRSE Social | .41** | — | .52** | .39** | −.32** | −.28** | 18.48 (6.45) | 19.33 (6.49) | 2.14 |

| 3. DRSE Emotional | .26** | .52** | — | .69** | −.39** | −.17** | 36.42 (7.66) | 37.30 (7.08) | 1.95 |

| 4. DRSE Opportunistic | .11** | .31** | .64** | — | −.36** | −.21** | 39.37 (4.86) | 40.74 (3.84) | 5.25*** |

| 5. Past 3 Month Consequences | −.28** | −.31** | −.36** | −.26** | — | .55** | 7.44 (9.22) | 5.96 (7.14) | −3.02*** |

| 6. Typical Weekly Drinks | −.29** | −.27** | −.18** | −.05 | .53** | — | 14.83 (13.04) | 8.73 (6.69) | −10.44*** |

Note. Male correlations above diagonal, female correlations below.

p < .01.

p < .001.

2.4.1 Model predicting typical weekly drinks

A three-step hierarchical multiple regression model examined the role of PBS use and the three factors of DRSE in predicting typical weekly drinking (Table 2). Given that previous research has found drinking motives to be the final common pathway to alcohol use (Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engels, 2005), the four drinking motive subscales were included as covariates. At Step 1, gender, Greek status, and all four subscales of the DMQ were entered to control for any gender and Greek-status differences as well as control for drinking motives. PBS use, social DRSE, emotional DRSE, and opportunistic DRSE were entered at Step 2. The interaction terms involving PBS use and each DRSE subscale were entered at Step 3. Predictors were standardized prior to calculating the interaction term.

Table 2.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression Evaluating Typical Weekly Drinks from PBS and DRSE

| Step 1

|

Step 2

|

Step 3

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | sr 2 | R2 Total | B | SE | β | sr 2 | R2 Total | B | SE | β | sr 2 | R2 Total | |

| .21*** | .27*** | .29*** | |||||||||||||

| Covariates | |||||||||||||||

| Gender | −3.03 | .27 | −.30*** | .09 | −2.36 | .28 | −.24*** | .7 | −2.38 | .27 | −.24*** | .05 | |||

| Greek Status | −1.58 | .24 | −.18*** | .03 | −1.50 | .23 | −.17*** | .03 | −1.48 | .23 | −.17*** | .03 | |||

| DMQ-R Social | 0.70 | .34 | .07 | .00 | 0.55 | .33 | .06 | .00 | 0.55 | .33 | .05 | .00 | |||

| DMQ-R Coping | 0.75 | .31 | −.08 | .00 | 0.29 | .32 | −.03 | .00 | 0.33 | .32 | −.03 | .00 | |||

| DMQ-R Enhancement | 1.98 | .34 | .20*** | .03 | 1.59 | .33 | .16*** | .02 | 1.61 | .32 | .16*** | .02 | |||

| DMQ-R Conformity | −0.50 | .30 | −.01 | .00 | −0.40 | .30 | −.04 | .00 | −0.36 | .29 | −.04 | .00 | |||

| Main Effects | |||||||||||||||

| DRSE Social | −0.92 | .33 | −.09** | .01 | −0.82 | .33 | −.08** | .00 | |||||||

| DRSE Emotional | 0.06 | .41 | .01 | .00 | −0.17 | .43 | .02 | .00 | |||||||

| DRSE Opportunistic | −0.96 | .36 | −.10** | .01 | −0.78 | .37 | −.08 | .00 | |||||||

| PBS | −1.91 | .30 | −.19*** | .03 | −1.83 | .30 | −.19*** | .03 | |||||||

| Two-Way Interactions | |||||||||||||||

| PBS x DRSE Social | 1.59 | .30 | .17*** | .02 | |||||||||||

| PBS x DRSE Emotional | −0.94 | .40 | −.10 | .00 | |||||||||||

| PBS x DRSE Opportunistic | 0.39 | .31 | .05 | .00 | |||||||||||

Note.

p < .01.

p < .001.

2.4.2 Model predicting alcohol consequences

A second, three-step hierarchical multiple regression model examined the role of PBS use and the three factors of DRSE in predicting negative, alcohol-related consequences over the past three months (Table 3). At Step 1, gender, Greek-status, and typical weekly drinking were entered to control for these factors. Step 2 included PBS use, social DRSE, emotional DRSE, and opportunistic DRSE. The interaction terms involving PBS use and each DRSE subscale were entered in Step 3. Predictors were standardized prior to calculating the interaction term.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression Evaluating Past Three Month Alcohol-Related Consequences from PBS and DRSE

| Step 1

|

Step 2

|

Step 3

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | sr 2 | R2 Total | B | SE | β | sr 2 | R2 Total | B | SE | β | sr 2 | R2 Total | |

| .21*** | .30*** | .31** | |||||||||||||

| Covariates | |||||||||||||||

| Gender | 0.47 | .26 | .06 | .00 | 0.58 | .23 | .07** | .00 | 0.55 | .23 | .07 | .00 | |||

| Greek Status | 0.13 | .20 | .02 | .00 | 0.00 | .19 | .00 | .00 | −0.04 | .19 | −.01 | .00 | |||

| Typical Weekly Drinking | 3.48 | .22 | .48*** | .20 | 2.83 | .22 | .39*** | .11 | 2.81 | .22 | .39*** | .11 | |||

| Main Effects | |||||||||||||||

| DRSE Social | −0.42 | .26 | −.05 | .00 | −0.48 | .26 | −.06 | .00 | |||||||

| DRSE Emotional | −1.72 | .31 | −.21*** | .02 | −1.32 | .33 | −.16*** | .01 | |||||||

| DRSE Opportunistic | −0.59 | .28 | −.07 | .00 | −0.74 | .29 | −.09** | .00 | |||||||

| PBS | −0.58 | .24 | −.07** | .00 | −0.62 | .24 | −.08** | .00 | |||||||

| Two-Way Interactions | |||||||||||||||

| PBS x DRSE Social | 0.01 | .26 | .00 | .00 | |||||||||||

| PBS x DRSE Emotional | 0.92 | .32 | .12** | .01 | |||||||||||

| PBS x DRSE Opportunistic | −0.36 | .25 | −.06 | .00 | |||||||||||

Note.

p < .01.

p < .001.

3. Results

3.1 Correlations and Mean Differences

Table 1 presents all correlations and means as a function of gender. Independent t tests revealed no significant mean differences between campuses overall and as a function of gender (ps > .01) for all variables; thus, campus differences are not discussed. All but one pair of variables were significantly correlated with each other (all ps < .01). The relationship between typical weekly drinks and opportunistic DRSE for females was not significant (p = .16). PBS use and each DRSE subscale were moderately and significantly correlated. Independent t tests revealed males experienced significantly more alcohol consequences (7.44 to 5.96, t = 3.02, p = .003) and reported consuming more drinks per week (14.83 to 8.73, t = 10.44, p < .001) than females. Females reported significantly higher PBS use (t = 9.47, p < .001) and DRSE opportunistic scores (t = 5.25, p < .001) than males.

3.2 Model Predicting Typical Weekly Drinks

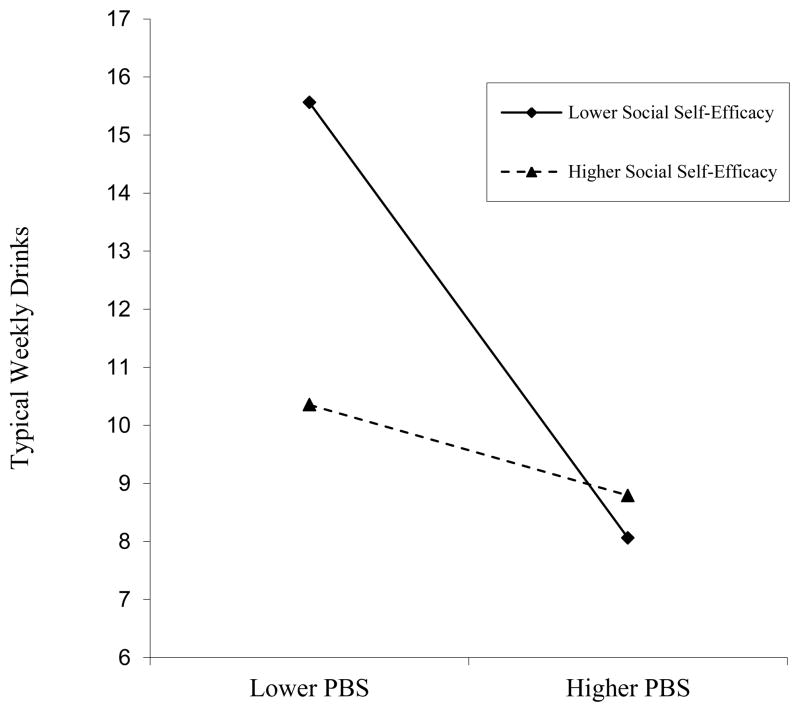

Hierarchical multiple regression revealed that gender (p < .001), Greek status (p < .001), and enhancement drinking motives (p < .001) were significant covariates. PBS use (p < .001) and social DRSE (p = .010) demonstrated significant main effects. There was one significant two-way interaction: PBS use x social DRSE (p < .001). The two-way interaction was graphed at one standard deviation below (low PBS) and one standard deviation above (high PBS) the mean (Figure 1; Aiken & West, 1991). Simple slope analysis was significant for low social DRSE (b = −3.42, p < .001). The slope was not significant for high social DRSE (b = −0.25, p = .569). For individuals with high social self-efficacy, PBS use had no effect on the number of typical weekly drinks. Alternatively, those low in social self-efficacy showed a dramatic decrease in drinks as their PBS use increased.

Figure 1.

Typical weekly drinking for PBS x social DRSE.

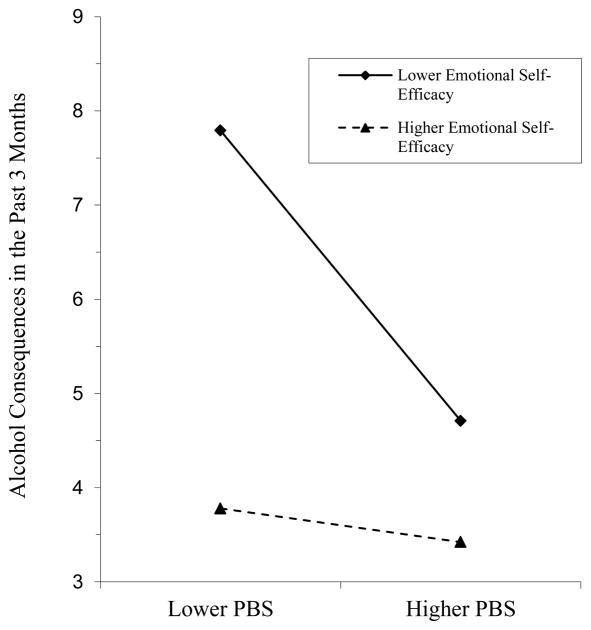

3.3 Model Predicting Alcohol Consequences

A second hierarchical multiple regression model revealed that typical weekly drinks was a significant covariate (p < .001) and gender approached significance (p = .015). Average PBS use, emotional DRSE, and opportunistic DRSE demonstrated significant main effects: PBS (p = .010), emotional DRSE (p < .001), and opportunistic DRSE (p = .010). Only one two-way interaction of PBS x emotional DRSE was significant (p = .004). The two-way interaction was graphed at one standard deviation below (low PBS) and one standard deviation above (high PBS) the mean (Figures 3; Aiken & West, 1991). Simple slope analysis revealed a significant difference from zero in the slope for low emotional DRSE (b = −1.41, p < .001), but not for high emotional DRSE (b = −0.18, p = .651). Participants high in emotional DRSE experienced a lower level of consequences than individuals low in emotional self-efficacy, regardless of PBS use. For individuals low in emotional self-efficacy, consequences decreased as PBS use increased.

4. Discussion

The present study examined the moderating impact of DRSE on the relationship between PBS use and alcohol consumption/consequences. Two hierarchical linear regression models demonstrated that both PBS use and DRSE emerged as unique predictors of weekly drinking and alcohol-related consequences while controlling for relevant factors. Main effects demonstrated that higher levels of PBS use were related to decreased drinking levels and alcohol consequences, consistent with our hypotheses and supporting previous research (Araas & Adams, 2008; LaBrie, Kenney, & Lac, 2010; LaBrie, Kenney, Lac, Garcia, & Ferraiolo, 2009; Martens et al., 2004; Martens et al., 2007; Sugarman & Carey, 2007). Interestingly, not every dimension of DRSE was related to drinking or consequences when controlling for PBS and other variables, and thus, not all the DRSE hypotheses were supported. Only the main effect of social DRSE was found to be associated with alcohol consumption, replicating previous research (Baldwin, Oei, & Young, 1993; Young et al., 1991). Further, only the main effects of emotional and opportunistic DRSE were related to alcohol consequences. Given that no prior studies to our knowledge have assessed the relationship between DRSE and negative alcohol-related consequences, the results provide a novel extension of existing research.

In addition to the main effects of PBS use and the three DRSE dimensions, two interaction effects emerged. First, for individuals low in social DRSE, greater PBS use was found to be related to lesser drinking while controlling for the covariates of gender, Greek status, and drinking motives. Students who were concurrently lower in both social DRSE and in the use of PBS reported the heaviest alcohol consumption, typically consuming about 15 drinks per week, in contrast to approximately 10 drinks per week reported by students who had higher social DRSE but used PBS less often. These findings align well with previous research documenting the protective effects on alcohol consumption associated with DRSE (Baldwin et al., 1993; Young et al., 1991). The study also extends current research by demonstrating that for participants lower in social DRSE, greater PBS use was associated with dramatically lower levels of drinks consumed per week, similar to consumption levels associated with higher DRSE.

Since social motives for drinking are among the most frequently endorsed reasons for drinking alcohol among college students (LaBrie, Hummer, Pedersen, 2007), and collegiate drinking occurs primarily in social contexts in which overt or implicit peer pressure influences alcohol consumption, these findings have important implications. In social settings where alcohol is present, individuals lower in social DRSE (i.e., individuals that find it difficult to resist drinking when “your friends are drinking,” “you see others drinking,” or “someone offers you a drink;” DRSEQ-R; Young et al., 1991) would likely be at risk for heavy drinking even when controlling for drinking motives. The current findings suggest that targeted interventions equipping these individuals with concrete and easy-to-use PBS may enable them to effectively reduce their alcohol consumption in such situations.

However, tests of simple slopes revealed that for individuals higher in social DRSE, the level of PBS use was not related to drinking in this sample. This suggests that higher levels of social DRSE are so influential in moderating drinking that level of PBS use has no additive influence. Despite previous research showing increased levels of PBS use to be consistently related to decreased drinking (LaBrie, Lac, Kenney, & Mirza, 2011; Martens, Martin, Littlefield, Murphy, & Cimini, 2011), this was not the case among students higher in social DRSE. Thus, promoting efficacy around drinking refusal, especially in social situations where peer influence is most important, may be another, albeit less utilized route, to reducing alcohol risk among college students. Finally, among participants lower in social DRSE, those that reported higher levels of PBS use drank nearly seven drinks less than those that reported lower levels of PBS use. Considering the large difference in weekly drinking as a function of PBS use, the results suggest that for students lower in social DRSE, increasing PBS use may be particularly effective in decreasing alcohol consumption.

Results also revealed a second interaction, demonstrating that for those low in emotional DRSE, using fewer PBS was associated with higher levels of alcohol-related consequences, while controlling for weekly drinking, gender, and Greek status. Among participants with lower emotional DRSE, greater use of PBS was found to offer significant protection against negative drinking outcomes. However, this group still experienced more alcohol consequences than did participants with greater DRSE, regardless of PBS use. Individuals reporting lower levels of emotional DRSE (i.e., individuals who report that they would unlikely be able to resist alcohol when they feel “nervous,” “angry,” or “sad” for example; DRSEQ-R; Young et al., 1991), may be seeking to lessen psychological distress by consuming alcohol. Drinking to cope, in turn, is associated with increased risk for experiencing negative consequences (Simons, Gaher, Correia, Hansen, & Christopher, 2005; Martens et al., 2008; Neighbors et al., 2007). Similarly, an increasing body of evidence indicates that students experiencing negative affect or symptoms of poor mental health are at greater risk for encountering drinking consequences (Geisner, Larimer, & Neighbors, 2004; LaBrie, Kenney, & Lac, 2010; Martens et al., 2008; Park & Grant, 2005; Weitzman, 2004). Perhaps deficits in self-regulation skills among students lower in emotional DRSE increase their risk for encountering drinking consequences, whereas greater use of PBS appears to greatly reduce this risk.

Once again, however, tests of simple slopes revealed a similar pattern as observed in the first interaction. That is, for individuals higher in emotional DRSE, PBS use was not related to alcohol consequences experienced in the past three months. Participants higher in emotional DRSE experienced fewer consequences than those with lower emotional DRSE regardless of PBS use, demonstrating that among individuals with higher levels of emotional DRSE, PBS use did not offer additional protection against drinking consequences. Again, these are surprising results as previous research has consistently found increased levels of PBS use were related to fewer alcohol consequences (Araas & Adams, 2008; Martens, Martin, Littlefield, Murphy, & Cimini, 2011).

Interestingly, although opportunistic DRSE predicted drinking consequences while controlling for drinking, it did not moderate the relationship between PBS use and alcohol outcomes. Given that lower opportunistic DRSE discriminates problem drinkers from non-problem drinkers (Lee, Oei, & Greeley, 1999), and that opportunistic drinking is indicative of greater salience of drinking behavior (Young et al., 1991), the impact of poorer DRSE in opportunistic drinking situations may be more relevant for individuals with established problematic patterns of drinking, such as alcohol dependent populations. Further, since the majority of PBS assessed may be most applicable to drinking in social situations, the protection afforded by greater PBS use may not extend to students drinking because of a lack of DRSE in opportunistic contexts such as when first arriving home, or when watching television (Young et al., 1991).

The current study, the first to our knowledge to concurrently assess DRSE, PBS use, and the interaction between the two, offers interesting insights. The results suggest that higher levels of DRSE are indeed associated with lesser drinking and related consequences, but moreover, greater DRSE appears to be more protective than PBS use, an established and increasingly popular intervention component. To our knowledge, no existing alcohol-related harm reduction interventions for college students directly aim to bolster students’ DRSE. However, research has found brief motivational enhancement interventions, which include building self-efficacy for behavioral change as a component of the Motivational Interviewing techniques (Miller & Rollnick, 2002; Rollnick & Allison, 2004), to be effective in reducing negative drinking outcomes among college students (see Larimer & Cronce 2002; 2007). In addition, limited research indicates the efficacy of drinking refusal skills training in clinical populations (Witkiewitz, Donovan, & Hartzler, 2012) and with adolescents (Komro, 2001; Schinke, Cole, & Fang, 2009). However, investigation is needed to build on existing research in order to assess how alcohol interventions geared toward college populations may be successfully adapted to include components specifically focused on building self-efficacy to resist drinking.

The current study also identifies the continued need for PBS interventions among collegiate populations. The results indicate that those lower in DRSE might greatly benefit from increasing their use of protective strategies, confirming the value of PBS in reducing drinking risk, and therefore supporting the increasing body of evidence highlighting the potential value of including PBS-skills-training components within alcohol-related harm reduction initiatives (Araas & Adams, 2008; LaBrie, Lac, Kenney, & Mirza, 2011; Martens, Martin, Littlefield, Murphy, & Cimini, 2011). Considering the utility of both DRSE and PBS use demonstrated in the study, future intervention research should explore the possible beneficial and synergistic effects of including both DRSE bolstering and PBS skills training in alcohol interventions.

Although these findings offer unique insights into the relationship between PBS use and DRSE in reducing alcohol harm among college students, the study is not without limitations. Firstly, the study relied on self-report data, and hence responses may have been subject to recall and self-presentation biases. Further, participants were high-risk drinkers who reported at least one heavy episodic drinking occasion within the past two-week period. Findings may therefore not be fully generalizable to college students in general, especially lower risk college student drinkers. Additionally, the analyses utilized cross-sectional data; a longitudinal design would undoubtedly yield greater understanding of this complex relationship. Considering this is the first study to look at the relationship between DRSE and consequences, future research is needed to determine how DRSE is distinct from other relevant factors such as coping drinking motives in predicting alcohol-related consequences. Finally, despite previous evidence that PBS use may vary by ethnicity (LaBrie, Lac, Kenney, & Mirza, 2011), current sample limitations did not permit examination of ethnicity in the PBS use and DRSE relationship. Future research that examines this relationship is therefore recommended. Despite the noted limitations, the present findings offer important insights, elucidating the relationship between DRSE and PBS use by providing evidence demonstrating that DRSE and PBS use are distinct constructs that exhibit unique relationships to risk reduction. Further, the study highlights the real potential for risk reduction by focusing prevention efforts on bolstering DRSE and increasing PBS use.

Figure 2.

Alcohol-related consequences in the past 3 months for PBS x emotional DRSE.

Highlights.

Simultaneously examines the impact of DRSE and PBS use on alcohol outcomes

Analyses incorporate the three DRSE subscales

DRSE and PBS use are differential predictors of alcohol risk

DRSE moderated the relationship between PBS use and alcohol outcomes

PBS use most beneficial for those lower in DRSE

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Sources

This research was funded by Grant R01 AA 012547-06A2 from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). NIAAA had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Contributors

Phillip Ehret, Tehniat Ghaidarov, and Joseph LaBrie have each contributed significantly to this manuscript. Specifically, Dr. LaBrie generated the idea for the study, designed the study, wrote the protocol, and oversaw its production. Phillip Ehret developed the specific hypotheses tested, performed the literature review, performed the statistical analyses, and drafted all sections of the paper. Tehniat Ghaidarov significantly assisted with drafting the discussion section and revising/editing all sections of the paper.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Phillip J. Ehret, Email: pehret@lmu.edu, Department of Psychology, Loyola Marymount University, 1 LMU Drive, Suite 4700, Los Angeles, CA 90045; Pn: (310) 338-3753

Tehniat M. Ghaidarov, Email: tehniat@alumni.kenyon.edu, Department of Psychology, Loyola Marymount University, 1 LMU Drive, Suite 4700, Los Angeles, CA 90045; Pn: (323) 807-3959

Joseph W. LaBrie, Email: jlabrie@lmu.edu, Department of Psychology, Loyola Marymount University, 1 LMU Drive, Suite 4700, Los Angeles, CA 90045; Pn: (310) 338-5238; Fx: (310) 338-7726.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA US: Sage Publications, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Araas T, Adams T. Protective behavioral strategies and negative alcohol-related consequences in college students. Journal of Drug Education. 2008;38(3):211–224. doi: 10.2190/DE.38.3.b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin AR, Oei TPS, Young R. To drink or not to drink: The differential role of alcohol expectancies and drinking refusal self-efficacy in quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption. Cognitive Therapy And Research. 1993;17(6):511–530. doi: 10.1007/BF01176076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Murphy JG, Carey KB. Readiness to change in brief motivational interventions: A requisite condition for drinking reductions? Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34(2):232–235. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LJ, Carey MP, DeMartini KS. Individual-level interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analytic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(11):2469–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H. Readiness to change, norms, and self-efficacy among heavy-drinking college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2006;67(1):131–138. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53(2):189–200. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6(2):117–128. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delva J, Smith MP, Howell RL, Harrison DF, Wilke D, Jackson DL. A study of the relationship between protective behaviors and drinking consequences among undergraduate college students. Journal of American College Health. 2004;53(1):19–26. doi: 10.3200/JACH.53.1.19-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt G. Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS): A harm reduction approach. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Geisner IM, Larimer ME, Neighbors C. The relationship among alcohol use, related problems, and symptoms of psychological distress: Gender as a moderator in a college sample. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29(5):843–848. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullo MJ, Dawe S, Kambouropoulos N, Stalger PK, Jackson CJ. Alcohol expectancies and drinking refusal self-efficacy mediate the association of impulsivity with alcohol misuse. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34(8):1386–1399. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter M, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24: Changes from 1998 to 2001. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:259–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA, Fromme K, Coppel DB, Williams E. Secondary prevention with college drinkers: Evaluation of an alcohol skills training program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58(6):805–810. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.58.6.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knee CR, Neighbors C. Self-determination, perception of peer pressure, and drinking among college students. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2002;32(3):522–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00228.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;27(7):841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Pedersen ER. Reasons for drinking in the college student context: The differential role and risk of the social motivator. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(3):393–398. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Kenney SR, Lac A. The use of protective behavioral strategies is related to reduced risk in heavy drinking college students with poorer mental and physical health. Journal of Drug Education. 2010;40(4):361–378. doi: 10.2190/DE.40.4.c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Kenney SR, Lac A, Garcia JA, Ferraiolo P. Mental and social health impacts the use of protective behavioral strategies in reducing risky drinking and alcohol consequences. Journal of College Student Development. 2009;50(1):35–49. doi: 10.1353/csd.0.0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Lac A, Kenney SR, Mirza T. Protective behavioral strategies mediate the effect of drinking motives on alcohol use among heavy drinking college students: Gender and race differences. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(4):354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention, and treatment: A review of individual-focused strategies to reduce problematic alcohol consumption by college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002:148–163. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention, and treatment revisited: Individual-focused college drinking prevention strategies 1999–2006. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(11):2439–2468. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Turner AP, Anderson BK, Fader JS, Kilmer JR, Palmer RS, Cronce JM. Evaluating a brief alcohol intervention with fraternities. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62(3):370–380. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Geisner IM, Lewis MA, Neighbors C, Larimer ME. Social motives and the interaction between descriptive and injunctive norms in college student drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(5):714–721. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee NK, Oei TS. The importance of alcohol expectancies and drinking refusal self-efficacy in the quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1993;5(4):379–390. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(93)90006-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee NK, Oei TPS, Greeley JD. The interaction of alcohol expectancies and drinking refusal self-efficacy in high and low risk drinkers. Addiction Research. 1999;7(2):91–102. doi: 10.3109/16066359909004377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Dimeff LA, Larimer ME, Quigley LA, Williams E. Screening and brief intervention for high-risk college student drinkers: Results from a 2-year follow-up assessment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66(4):604–615. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Ferrier AG, Cimini MD. Do protective behavioral strategies mediate the relationship between drinking motives and alcohol use in college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(1):106–114. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Ferrier AG, Sheehy MJ, Korbett K, Anderson DA, Simmons A. Development of the Protective Behavioral Strategies Survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66(5):698–705. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Martin JL, Littlefield AK, Murphy JG, Cimini MD. Changes in protective behavioral strategies and alcohol use among college students. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;118(2–3):504–507. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Neighbors C, Lewis MA, Lee CM, Oster-Aaland L, Larimer ME. The roles of negative affect and coping motives in the relationship between alcohol use and alcohol-related problems among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69(3):412–419. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Pederson ER, LaBrie JW, Ferrier AG, Cimini MD. Measuring alcohol-related protective behavioral strategies among college students: Further examination of the Protective Behavioral Strategies Scale. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21(3):307–315. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Taylor KK, Damann KM, Page JC, Mowry ES, Cimini MD. Protective behavioral strategies when drinking alcohol and their relationship to negative alcohol-related consequences in college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18(4):390–393. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe S, Boyd CJ, Couper MP, Crawford S, D’Arcy H. Mode effects for collecting alcohol and other drug use data: Web and U.S. mail. Journal Of Studies On Alcohol. 2002;63(6):755–761. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rose GS. Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. American Psychologist. 2009;64(6):527–537. doi: 10.1037/a0016830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Dillard AJ, Lewis MA, Bergstrom RL, Neil TA. Normative misperceptions and temporal precedence of perceived norms and drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67(2):290–299. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(4):556–565. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TF, Xuan Z, Lee H, Weitzman ER, Wechsler H. Persistence of heavy drinking and ensuing consequences at heavy drinking colleges. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2002;70(5):726–734. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oei TPS, Jardim CL. Alcohol expectancies, drinking refusal self-efficacy and drinking behaviour in Asian and Australian students. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;87(2–3):281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;(SUPPL14):23–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Grant C. Determinants of positive and negative consequences of alcohol consumption in college students: Alcohol use, gender, and psychological characteristics. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30(4):755–765. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. Social norms and the prevention of alcohol abuse in collegiate contexts. Journal of Studies in Alcohol. 2002;(SUPPL14):164–172. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Allison J. Motivational Interviewing. In: Heather N, Stockwell T, editors. Handbook of Treatment and Prevention of Alcohol Problems. England: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2004. pp. 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Stacy AW, Sussman S, Dent CW, Burton D. Moderators of peer social influence in adolescent smoking. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1992;18(2):163–172. [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM, Correia CJ, Hansen CL, Christopher MS. An affective-motivational model of marijuana and alcohol problems among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19(3):326–334. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.19.3.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugarman DE, Carey KB. Drink less or drink slower: The effects of instruction on alcohol consumption and drinking control strategy use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23(4):577–585. doi: 10.1037/a0016580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Kelley K, Weitzman ER, San Giovanni J, Seibring M. What colleges are doing about student binge drinking: A survey of college administrators. Journal Of American College Health. 2000;48(5):219–226. doi: 10.1080/07448480009599308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts: Findings from 4 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study surveys: 1993–2001. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50(5):203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Nelson TF. What we have learned from the Harvard School of Public Health college alcohol study: Focusing on college student alcohol consumption and the environmental conditions that promote it. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69(4):481–490. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Nelson T, Lee JE, Seiberg M, Lewis C, Keeling R. Perception and reality: A national evaluation of social norms marketing interventions to reduce college students’ heavy alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64(4):484–494. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman ER. Poor mental health, depression, and associations with alcohol consumption, harm, and abuse in a national sample of young adults in college. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2004;192(4):269–277. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000120885.17362.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50(1):30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RM, Hasking PA, Oei TPS, Loveday W. Validation of the Drinking Refusal Self-Efficacy Questionnaire – Revised in an adolescent sample (DRSEQ-RA) Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(4):862–868. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RM, Conner JP, Ricciardelli LA, Saunders JB. The role of alcohol expectancy and drinking refusal self-efficacy beliefs in university student drinking. Alcohol & Alcoholism. 2006;41(1):70–75. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RM, Oei TP, Crook GM. Development of a drinking self-efficacy questionnaire. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 1991;13(1):1–15. [Google Scholar]