Abstract

Introduction

We recently completed a strategic planning process to better understand the development of our five-year-old PBRN and to identify gaps between our original vision and current progress. While many of our experiences are not new to the PBRN community, our reflections may be valuable for those developing or re-shaping PBRNs in a changing health care environment.

Lessons Learned

We learned about the importance of: (1) Shared vision and commitment to a unique patient population; (2) Strong leadership, mentorship, and collaboration; (3) Creative approaches to engaging busy clinicians and bridging the worlds of academia and community practice; (4) Harnessing data from electronic health records and navigating processes related to data protection, sharing, and ownership.

Challenges Ahead

We must emphasize research that is timely, relevant, and integrated into practice. One model supporting this goal involves a broader partnership than was initially envisioned for our PBRN, one which includes clinicians, researchers, information architects and quality improvement experts partnering to develop an Innovation Center. This Center could facilitate development of relevant research questions while also addressing ‘quick-turnaround’ needs.

Conclusions

Gaps remain between our PBRN’s initial vision and current reality. Closing these gaps may require future creativity in partnership building and nontraditional funding sources.

Keywords: practice-based research, community health, primary care, electronic health records, health care safety net

Over the past several decades, the practice-based research network (PBRN) model has flourished, providing community laboratories for answering questions relevant to primary care.1–4 The heightened need for research conducted in “real world” settings has spurred the development of new and somewhat non-traditional PBRNs across many specialties and in unique settings. Having recently developed a PBRN in this “post-modern” era, we have learned valuable lessons and look forward to increasing the relevance of our work and sustaining our network in today’s changing health care environment.

We celebrated our PBRN’s fifth year by interviewing many founding members and hosting a strategic planning retreat to reflect on our initial vision and plan for the future. This process helped us better understand how our PBRN was developed, challenges to our sustainability, and gaps between the original vision and our current progress. While our challenges are not necessarily new to the PBRN community, reflections on our experiences in this developmental stage may benefit others.

Who Are We?

Founded in 2006 and registered with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) in 2007, our PBRN was created to complement the unique strengths of the OCHIN network. Originally called the Oregon Community Health Information Network (renamed OCHIN as other states joined), OCHIN is a collaborative member-based organization of federally-qualified health centers (FQHCs) and similar entities providing a primary health care “safety net” to vulnerable populations. Using a collaborative learning organization model, OCHIN facilitates its members’ adoption of health information technology to improve patient care quality. To this end, OCHIN maintains one electronic health record (EHR) with a single master patient index linked across all clinic sites. OCHIN is recognized by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) as a Health Center-Controlled Network and now has more than 62 member organizations with over 200 clinics, serving more than 1.2 million unique patients across 12 states (with ~10 million annual visits).5

The OCHIN PBRN was originally named Safety Net West; we are now working to give it a name more inclusive of members beyond the western states. The PBRN currently manages a portfolio of nine active research grants, with eleven additional grant submissions since June 2011.5 Our active grants range from large population-based data-only studies to EHR- and internet-based intervention research. Topic areas focus on issues relevant to primary care: cardiovascular disease, diabetes, depression, obesity, asthma, child health quality measures, and clinical decision support tools. Two infrastructure grants currently fund staff and operations to develop research processes and partnerships. Our PBRN includes a steering committee of 18 and an Executive Committee of five (Chair, Vice-Chair, Executive Director, Operations Director and PBRN Coordinator). We have built key partnerships with two local academic research centers.

What Have We Learned?

Foundation Built on a Shared Vision and Commitment

A major facilitator in the development of our PBRN was the shared vision for conducting high quality research in the safety net. One founding member commented, “There was an ideological commitment to serving the greater good, and that outweighed individual clinic interests.” The PBRN was founded on this unity of purpose: “We could do research as a community.” Founding members had a clear understanding of the added value of being part of a network; one noted: “At the end of my career, I’ll look back and say that this was one of the most exciting, and unforeseen, opportunities I ever had.” Table 1 summarizes lessons learned.

Table 1.

Lessons Learned from Our PBRN’s Development

| Lessons Learned | Key Tips |

|---|---|

| Shared Vision and Commitment |

|

| Leadership, Mentorship and Collaboration |

|

| Engaging Busy Clinicians |

|

| Bridging Academia and Community |

|

| Harnessing EHR Data |

|

The shared vision and commitment to the safety net has kept a dedicated and cohesive group of providers, researchers and staff (mostly volunteers) inspired and moving forward. While these factors both shaped our identity and helped us to target grant funds earmarked for priority populations, the importance of having a unique identity, shared vision, and clear purpose must be balanced with a willingness and ability to be flexible and adaptable, lest we become too narrowly focused, which could reduce options for innovation, funding, or sustainability.

Leadership, Mentorship, Collaboration

Our PBRN benefited from passionate leaders, internal institutional support (money, staff, and space), and prior relationships in Oregon’s health care community. External resources and mentors were also crucial, such as guidance from other PBRNs and the opportunity to attend the national PBRN conference sponsored by AHRQ. Our PBRN also benefited from cross-organizational collaborations, as described by one of the interviewees: “When the lines are blurred between organizations, and people wonder who works for who, that’s good! That means there’s true cooperation and sharing of resources.”

Engaging busy clinicians

Although the opportunity to develop a PBRN within OCHIN was unique, the overall desire to come together to learn from each other and share resources is similar to that reported by others, who found that a major influence supporting PBRN development was participants’ perception that a PBRN could add value both to research opportunities and to practice quality.6,7

Despite our vision and commitment, it can still be difficult to engage busy clinicians with many competing priorities. We struggle to involve clinicians in all aspects of network decision-making, from setting the research agenda by identifying “questions that come up in clinic every day” to ongoing participation in the research itself. Further, while being a PBRN of community health centers has been a facilitator, these practices are often stretched to care for as many patients as possible with limited resources, and thus have limited time to engage in research activities. We found that clinicians recently retired or working part-time may have more time and energy to contribute. As grant budgets are prepared, we strive to advocate for realistic compensation for engaged providers and clinics, including both provider time and clinic impact fees.

Bridging the “two worlds” of academia and community

While a motivating factor of other PBRNs,6–9 our two “different worlds” do not always understand each other, possibly because our PBRN is based in the community rather than an academic setting. Building cohesion among PBRN clinicians and researchers required time to develop relationships so that our clinicians and researchers better appreciate each others’ worlds. This effort was key to our success, as having clinician champions for research projects was invaluable to recruiting clinics to participate in our first intervention study. Similarly, we benefited from engaging researchers committed to longitudinal partnerships with clinicians. It also helped to include “boundary spanners” on the team who have both clinical and research experience.

Harnessing EHR data

The opportunity to harness data from many practices was another major facilitator of our PBRN’s development and echoes others’ observations about the power of networks to collect data on large numbers of diverse patients.7,9 Our PBRN’s data on a large patient population is in one shared and linked EHR which is centrally maintained and housed at OCHIN. This unique data resource helped to catalyze the formation of our PBRN and obtain some early grants to conduct secondary data analyses.

While this data resource facilitated our PBRN’s development, it also raised concerns regarding data ownership that needed careful attention. PBRNs with a common EHR, or the ability to merge data from multiple EHRs into a common repository, must establish trust and boundaries around data sharing. Much time was required to negotiate policies related to compliance about data protections, sharing and ownership. In the current era of EHRs and multi-site network building, such issues are increasingly relevant; the time required to develop these policies cannot be underestimated. It is important to have realistic expectations and the patience to move through the requisite (and often tedious) discussions about data-sharing policies and the more general procedures and bylaws required to govern a new organization. We also met frequently with our IRB to educate their analysts about our work and to get their assistance with the development of data sharing policies and data use agreements.

Where are we going?

In the next phase of our development, our PBRN needs to address several identified gaps between our initial vision and current reality. Notably, we aspire to make our research more timely, relevant, and better integrated into practice; working towards that goal requires creating synergy between community clinicians and academicians.9 Achieving this synergy remains a challenge to us and all PBRNs. We now envision a model that engages clinicians, researchers, information architects and quality improvement experts partnering together in an Innovation Center.

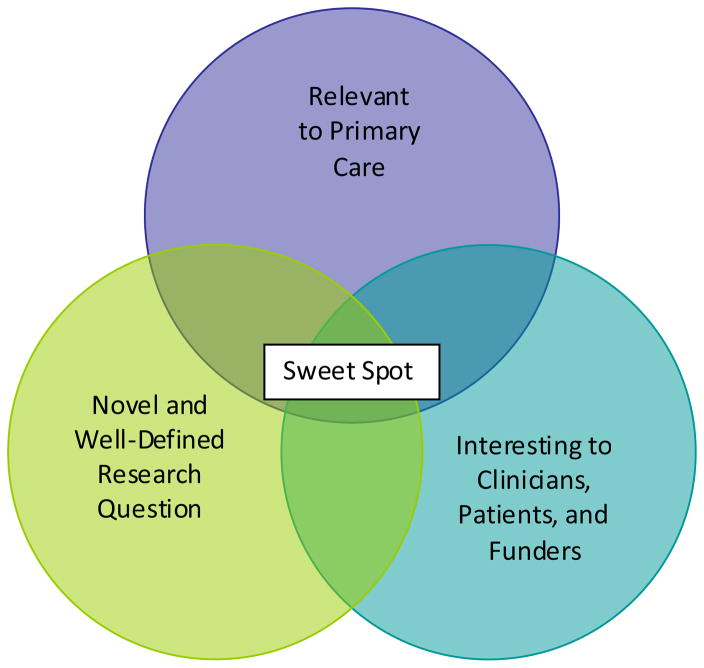

An Innovation Center model could foster clinician, staff, and patient involvement and engagement in a portfolio of activities that directly improve clinical practice, inform policy, and also inspire future research projects. Such collaboration could support opportunities to use EHR data to answer clinical, quality improvement, and policy questions; to support the creation of clinical decision support tools; to develop data aggregation tools that enable sophisticated panel management to care for an entire population; and to transform other automated processes to support and better align with population care and outcomes. This model could facilitate the development of relevant research questions while also addressing ‘quick-turnaround’ needs, including answering queries rapidly using an EHR data warehouse. We aim to establish processes and capabilities for data aggregation that support research but also bring day-to-day value to clinicians and provide timely information for policy makers. Others have described similar models.10,11 Whatever we call this model, we are in search of the PBRN “sweet spot:” a combination of research that is (1) relevant to primary care and day-to-day needs, (2) novel and well-defined so that it contributes to the literature, and (3) interesting to clinicians, policy-makers, patients, and funders.

Funding for an Innovation Center or a similar model would need to come from multiple sources. First, this type of resource adds value so could be sustained through membership or consulting fees. The added value from this resource assumes that practices could incorporate the costs into an alternative payment model which incentivizes practices to take better care of populations and have data to show better outcomes. Second, there would be opportunities for training in such a Center, especially if affiliated with degree programs; funding could also be sought to support fellowship programs. Third, researchers would play a key role in evaluating new innovations and their impact. This would involve seeking grant funding to study the translation of interventions proven effective in one setting for implementation in another setting, supporting learning about the dissemination of new ideas and diffusion of innovations across diverse clinics and patient populations.

CONCLUSIONS

In developing our “post-modern” PBRN, we traveled similar paths and learned many lessons similar to those who have gone before us. To continue our momentum, we must focus on bridging the gaps between traditional research and its relevance to primary care settings. This may require forging unique partnerships and seeking nontraditional funding sources in the future.

Figure 1.

The PBRN “Sweet Spot”

Acknowledgments

Funding Statement: This study was supported by grant number UB2HA20235 from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), grant number RC4LM010852 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Library of Medicine, the Kaiser Permanente Northwest Center for Health Research, and the Oregon Health & Science University Department of Family Medicine.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the 19 PBRN members whose comments and ideas from recent interviews contributed to this commentary. We would also like to thank Pam Rechel of Braveheart Consulting in Portland, OR, for providing facilitation at our strategic planning retreat, and Jee Park of OCHIN for administrative assistance.

Footnotes

Conflicting or Competing Interests: None to disclose.

HUMAN SUBJECTS CONSIDERATIONS

While not an original research piece, this commentary is based on information learned in the qualitative analysis of interviews with 19 founding PBRN members, as part of a larger study approved by our affiliated institutional review board (eIRB# 00007643).

References

- 1.Lindbloom EJ, Ewigman BG, Hickner JM. Practice-based research networks: the laboratories of primary care research. Med Care. 2004;42(4 Suppl):III45–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mold JW, Peterson KA. Primary care practice-based research networks: working at the interface between research and quality improvement. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3 (Suppl 1):S12–20. doi: 10.1370/afm.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green LA, Dovey SM. Practice based primary care research networks. They work and are ready for full development and support. BMJ. 2001;322(7286):567–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7286.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green LA, Hickner J. A short history of primary care practice-based research networks: from concept to essential research laboratories. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(1):1–10. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.19.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeVoe JE, Gold R, Spofford M, Chauvie S, Muench J, Turner A, et al. Developing a network of community health centers with a common electronic health record: description of the Safety Net West Practice-based Research Network (SNW-PBRN) J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(5):597–604. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.05.110052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niebauer L, Nutting PA. Practice-based research networks: the view from the office. J Fam Pract. 1994;38(4):409–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fagnan LJ, Handley MA, Rollins N, Mold J. Voices from left of the dial: reflections of practice-based researchers. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(4):442–51. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2010.04.090189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green LA, Niebauer LJ, Miller RS, Lutz LJ. An analysis of reasons for discontinuing participation in a practice-based research network. Fam Med. 1991;23(6):447–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green LA, Hames CG, Nutting PA. Potential of practice-based research networks: experiences from ASPN. Ambulatory Sentinel Practice Network. J Fam Pract. 1994;38(4):400–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams RL, Rhyne RL. No longer simply a Practice-based Research Network (PBRN) health improvement networks. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(5):485–8. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.05.110102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glasgow RE, Green LW, Taylor MV, Stange KC. An Evidence Integration Triangle for Aligning Science with Policy and Practice. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(6):646–654. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]