Abstract

Community partnered research and engagement strategies are gaining recognition as innovative approaches to improving healthcare systems and reducing health disparities in underserved communities. These strategies may have particular relevance for mental health interventions in low income, minority communities in which there often is great stigma and silence surrounding conditions such as depression and difficulty in implementing improved access and quality of care. At the same time, there is a relative dearth of evidence on the effectiveness of specific community engagement interventions and on the design, process, and context of these interventions necessary for understanding their implementation and generalizability.

This paper evaluates one of a number of community engagement strategies employed in the Community Partners in Care (CPIC) study, the first randomized controlled trial of the role of community engagement in adapting and implementing evidence-based depression care. We specifically describe the unique goals and features of a community engagement “kickoff” conference as used in CPIC and provide evidence on the effectiveness of this type of intervention by analyzing its impact on: 1) stimulating a dialogue, sense of collective efficacy, and opportunities for learning and networking to address depression and depression care in the community, 2) activating interest and participation in CPIC’s randomized trial of two different ways to implement evidence-based quality improvement (QI) programs for depression across diverse community agencies, and 3) introducing evidence-based toolkits and collaborative care models to potential participants in both intervention conditions and other community members.

We evaluated the effectiveness of the conference through a community-partnered process in which both community and academic project members were involved in study design, data collection and analysis. Data sources include participant conference evaluation forms (n=187 over two conferences; response rate 59%) and qualitative observation field notes of each conference session. Mixed methods for the analysis consist of descriptive statistics of conference evaluation form ratings, as well as thematic analysis of evaluation form write-in comments and qualitative observation notes. Results indicate the effectiveness of this type of event for each of the three main goals, and provide insights into intervention implementation and use of similar community engagement strategies for other studies.

Keywords: community engagement, community conference, community-partnered research, collective efficacy, community of practice, depression care, improvement

INTRODUCTION

Community partnered research and engagement strategies are gaining recognition as innovative approaches to improving local healthcare systems and reducing health disparities in underserved communities of low income, historically disadvantaged minority populations. These strategies may have particular relevance for mental health interventions in these communities in which there often is great stigma and silence surrounding conditions such as depression and difficulty in implementing improved access and quality of care. At the same time, there is a relative dearth of evidence on the effectiveness of specific community engagement interventions and on the design, process, and context of these interventions necessary for understanding their implementation and generalizability beyond the initial group of stakeholders among which they were developed.

Community Partners in Care (CPIC) is a community-partnered participatory research (CPPR) study in two underserved areas in Los Angeles and the first randomized controlled trial of the use of community engagement as an approach to adapt and disseminate evidence-based depression care. CPPR is a variant of community based participatory research (CBPR) that emphasizes equal partnership with genuine power sharing and consistent collaboration in all phases of the research. Equal partnership is intended to encourage two-way capacity development as academic partners increase their ability to work in and adapt interventions to community settings and community partners enhance their skills at analyzing and applying research findings to solve problems that affect their communities.1-3.

The CPIC study explicitly tests the effectiveness of community engagement (CE) strategies to motivate and mobilize community stakeholders to participate and take ownership in a CPPR project for improving depression outcomes. This paper evaluates one of a number of community engagement strategies employed in the CPIC study. We specifically describe and assess the effectiveness of a “kickoff” community engagement conference used during the initial stage of the CPIC trial as a large-group, event-based intervention for activating individuals and agencies in a community-wide effort to improve access and quality for depression care.

CONCEPTS UNDERLYING COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT PROCESSES

Community engagement approaches spend much effort on building relationships through sharing perspectives and joint activities. To facilitate these efforts, CE strategies include the use of particular partnership structures, such as a steering council to identify priorities and coordinate efforts and workgroups to address specific issues or tasks. These approaches may also employ staged implementation sequences, such as “Vision” (developing a vision and mission), “Valley” (developing, implementing, and evaluating action plans), and “Victory” (developing products, dissemination, and celebration).4-6 In the CPIC project, the purpose of these community engagement strategies is for diverse community and other stakeholders to “build a village” that supports various opportunities to learn about and engage in evidence-based improvement of depression care. One of the expectations being tested is that the participatory engagement and building of relationships and networks among partners will stimulate sharing of resources and new local solutions that facilitate access to quality improvement programs and treatments across the community.7

This “building a village” involves developing what are termed collective efficacy and a community-of-practice among stakeholders interested in addressing a community health need. Collective efficacy has been described as a certain sense of “Yes we can”, a shared belief in a group’s capability to solve a given community problem.8-10 Such collective efficacy is reflected in such statements as “I feel hopeful our community can make progress on improving access to care for depression” or “I am confident our community can create adequate resources to improve depression care”.8 Others have characterized collective efficacy as a combination of social cohesion among a group (i.e., “This is a close-knit group”) and the willingness of group members to act on behalf of the common good (i.e., “People in this community are willing to help their neighbors”).11, 12 As these statements indicate, collective efficacy represents a shared desire and readiness to solve a particularly pressing community problem or set of problems.

In addition to attempting to leverage the capacity of a group to solve a collective problem, CPIC’s community engagement approach calls for building a dynamic learning and collaborative network to support specific interventions and action, similar to what some describe as a community-of-practice.13, 14 This concept has been used to define groups of individuals with like interests, typically of a technical or professional nature (or other calling), who share knowledge and skills in a free-flowing manner across community and organizational boundaries to transfer innovation and best practices within a network they create. Studies from the organizational learning and development literature indicate that when such communities or networks develop a constant interchange of ideas, sense of trust, and history of solving problems together among members, they may cultivate a common identity, purpose, and solidarity that serves to reinforce and perpetuate the group.15, 16 Research in health care interventions and quality improvement has suggested that developing a community-of-practice around a particular intervention has the potential to increase its sustainability over time.17-19

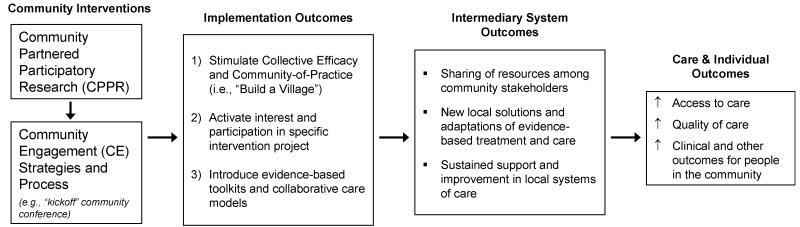

Figure 1 depicts the intended effects of community participatory and engagement interventions described above, from implementation outcomes, to intermediary system outcomes, to the ultimate outcomes of improved care and clinical, social, and economic outcomes for individuals in need or at-risk within communities.

Figure 1.

Logic Model of Effects of Community Engagement and Participatory Interventions

This paper focuses on the first set of hypothesized linkages, from the community interventions to implementation outcomes, with the subsequent chain of effects to be analyzed in later stages of the CPIC study. However, despite the wide use of community engagement and similar strategies in the fields of community organizing and development,20 little research exists in the health services literature on any of these sets of effects, particularly in the context of a randomized controlled study to address community health needs. A key imperative for research is to examine how such strategies are implemented on the ground and the extent to which they do or do not generate expected implementation and intermediary system outcomes, in order to better generalize the strategies to other settings and differentiate between whether they were (in)adequately implemented versus (in)adequately effective.21, 22

SPECIFIC EVALUATION AIMS OF THE COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT “KICKOFF” CONFERENCES

Two “kickoff” community engagement conferences—one in each of the project’s geographic study areas—were held during the initial stage of the CPIC trial phase to orient and further recruit agency participants. This paper specifically describes the unique goals and features of these community engagement conferences, details how they were implemented, and evaluates their effectiveness in achieving the following implementation outcomes:

Stimulating a dialogue, sense of collective efficacy, and opportunities for learning and networking that will help “build a village” for addressing depression and depression care in the community,

Specifically activating interest and participation in CPIC’s randomized trial of two different ways to implement evidence-based quality improvement (QI) programs for depression across diverse community agencies, and

Introducing evidence-based toolkits and collaborative care models to potential participants in both intervention conditions.

DESIGN OF CPIC’S COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT “KICKOFF” CONFERENCES: KEY GOALS AND FEATURES

Design of CPIC

CPIC is an experimental study that randomizes participating agency sites of diverse kinds (e.g., health and mental health clinics, social services, and community-trusted organizations such as churches and schools) into two conditions reflecting different ways of implementing depression care improvement. The first is a low intensity dissemination condition called Resources for Services (RS) that provides agency sites with training and limited technical support on evidence-based toolkits and collaborative care models for depression. The second is a high intensity, community engagement and network development condition called Community Engagement and Planning (CEP) that provides the same resources as the low intensity condition, plus support for agency sites to collectively plan and commit to sharing resources and responsibility for depression care.23

The CPIC study is fielded in two racially and ethnically diverse, underserved communities in Los Angeles County – South Los Angeles and the Hollywood/Metro area. A kickoff conference lasting approximately three-quarters of a day was held for each of these areas. Since the kickoff conference was conducted before agency sites in an area were randomized and the conference was to include initial orientations to the depression care toolkits and collaborative care models for both conditions, all enrolled sites were invited to participate in a kickoff conference. This provided sites randomized to the RS condition an initial experience of community engagement (particularly the developing of a vision and mission for improving community depression care) before they began a series of teleconference training calls, while the CEP condition went on to start their more intensive facilitated community planning and network development process.

In addition, the kickoff conference in each area was broadly publicized and open to members of the general public and other organizations not enrolled in the study at that time. Thus, the conferences provided an opportunity to attract potentially new agency sites and expand interest beyond study participants in order to generate a dialogue, knowledge of approaches to improving depression care, and layers of awareness and support of the project in the wider community. The kickoff conference for the South Los Angeles study area was held on May 29, 2009 and for the Hollywood/Metro area on September 11, 2009.

Design of the “Kickoff” Conferences

Given the CPIC study’s grounding in CPPR and the community engagement goals of the project, it was critical that the conferences not only imparted information on the project and depression (related to Goals 2 & 3 of the conference), but also focused on building relationships and inspiring a community vision for depression care at the outset of the study (related specifically to Goal 1 listed above). To accomplish this, the conference organizers on the project’s overall Steering Council spent several months deliberately attempting to incorporate features that would further these design goals. These features included a philosophy emphasizing the perspectives and leadership of both community and academic partners, a programmatic structure and use of session formats intended to encourage dialogue and exchange among attendees, and physical and logistical arrangements supportive of community participation and interaction.

At the beginning of each conference, organizers explicitly raised the issue of community and academic balance, as well as attempted to model this philosophy in practice throughout the events. During the introductory sessions, the study’s academic and community Principle Investigators explained the CPPR principles on which CPIC is based, stressing that all activities are co-led by community and academic partners and decisions made with equal participation. They also described the history of their collaboration in concrete terms, contrasting such a community-partnered approach to more traditional research studies. In turn, attendees were invited to share their thoughts and concerns regarding community-academic relations. For example, one community attendee commented during the group discussion that “I participated in another project [that] had a religious background, African-centric” in which the academics later relegated community members to “a back seat on that project. It was Afro-centric at first, and then it was more white.” She wanted to know how the CPIC project would be different.

Conference organizers additionally designed the program content to reflect a strength-based view of community expertise and resources, acknowledging the value of all types of evidence, including both expert and experiential. For instance, separate conference sessions highlighted collaborative models and experiences of local community agencies, as well as collaborative care models developed and studied by academics.

The programmatic structure of the conferences similarly modeled CPPR principles in practice, with all sessions having both academic and community co-leads. Moreover, a variety of session formats were used to engage attendees and promote interactive dialogue, including a skit depicting experiences of individuals trying to access and provide depression care in the community, panel sessions accompanied by Question & Answer periods, open discussions organized around general topics or community concerns, and dedicated group participatory activities (e.g., an activity of linking arms and discussing a parable about the preparation of a pot of soup to feed a hungry community). In all sessions, discussion leaders encouraged sharing of personal experiences with depression and depression care in the community. Many of these stories were of personal experiences with depression—such as a community member who described the mental health ravages of being transient (like on a “hamster wheel”, the cycle starts to become normal) and going through intake in various homeless programs, but never being connected to mental health services. Others described their despair as case managers, nurses, or clergy not able to help or find help for community members they serve who have depression. This sharing of personal stories, testimonials, and even anecdotes was used as a method comfortable to many people for sharing perspectives, concerns, and passions in meaningful—and at times moving—ways, that may also stimulate others to join a dialogue and inspire a common search for solutions.

The morning portion of the conferences consisted of whole-group sessions so that all attendees would experience the same introductory information, community sharing and visioning discussions, and opportunities for networking with other participants. After the provided lunch, the conferences consisted of concurrent sessions focusing on specific toolkits and components of the collaborative care model for depression, such as Medication Management, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), and Care Management and Outreach.24 These afternoon sessions were oriented toward individuals and agencies participating in CPIC’s trial of the two implementation conditions but included other attendees (e.g., from the general community) as well.

Other features related to logistics and use of the conference space may not appear so different than a typical community-based research conference but were considered by organizers from CPIC’s Steering Council as important to supporting the community engagement principles and aims of the event. These arrangements included seating around multiple large round tables (as opposed to an auditorium-style set-up) that provided opportunity for a mix of agency representatives, community activists, academics, and other attendees to sit together. The breakfast, light snacks, and lunch served throughout the conference were intended to stimulate networking and informal discussion among attendees. Likewise, conference venues were chosen within the study area communities; conference registration, food, and all materials were provided without charge to attendees; continuing education units and medical education credits (CEU/CME) were offered to help professional service providers justify their participation; and effort was made to welcome and introduce attendees to others during the breakfast upon arrival. All of this was meant to enhance the inclusive and community-oriented nature of the conferences.

Lastly, conference organizers attempted to tailor the program and content of the conferences to the two study communities, which represented different mixes of stakeholders and histories of collaboration. For example, several CPIC partners had previously held similar CPPR-based conferences in South Los Angeles, led by a community partner that has developed and extensively used community engagement models. Based on those experiences, the kickoff conference in that area was particularly attentive to historical concerns of the African-American community related to trust with academic researchers and to providing a more structured sharing of community-derived service delivery models from lead local agencies as experts. The conference in the Hollywood/Metro area, which was expected to attract a different set of diverse stakeholders (including Korean and gay/lesbian organizations, and larger numbers of licensed professionals), placed earlier emphasis on the evidence-based models of depression care and did not include the skit, which had been created and performed by South LA community activists.

EVALUATION METHODS AND DATA

We assessed the effectiveness of the conferences through a community-partnered approach in which both community and academic research partners from CPIC’s Implementation Evaluation Committee were involved in all aspects of conference evaluation design, data collection and analysis. The conference evaluation design also incorporated a mix of quantitative and qualitative methods, including conference evaluation forms (with both closed-ended survey items and write-in comments)25 and qualitative field observation notes. This mixed method approach was intended to document self-reported experiences of attendees as systematically as possible while being attentive to group dynamics and observed behavior within the conference.

The conference evaluation forms consisted of an overall conference evaluation questionnaire (n=187 total across the two conferences; average response rate of 59%)26 and separate conference evaluation questionnaires for each of the four afternoon breakout sessions (response rates per breakout session ranged from 69% to 100%, except for one with 25%).27 At each conference, two academic and two community research partners took field observation notes. Both a community and an academic partner took observation notes of all morning sessions. Each afternoon breakout session was observed by only one research partner (either academic or community). The observation notes for each conference were combined into one document, which was then reviewed by the entire Implementation Evaluation Committee (4 community and 7 academic partners) to clarify discrepancies and supplement observations. Differences in observations and perspectives on which evaluation committee members did not reach agreement were also noted in the final set of consensus observation notes, which were then used for analysis.

The qualitative analysis of the consensus observation notes and of the open-ended evaluation form comments focused on identifying key themes related to the goals of the conference. Community and academic partners involved in the analysis worked in pairs to identify comments from each data source related to the three goals, and then to categorize those comments into sub-groupings reflecting common themes. Themes were then shared with all community and academic partners participating in the analysis, who decided on final sets of themes by consensus. For the quantitative data, the community and academic partners involved in the analysis first ascertained as a group the rating items from the conference evaluation forms that related to each conference goal. The lead author then conducted the descriptive statistical analyses for the indicators selected.

For each conference goal, we present evidence from each of our data sources (i.e., descriptive statistics from the closed-ended evaluation form items, key themes and illustrative quotes from the write-in comments and observation notes) to evaluate the effectiveness of the conference and identify lessons learned. Both academic and community partners on CPIC’s Implementation Evaluation Team were involved in analyzing, interpreting, and writing up results from each data source.

RESULTS

Conference attendee characteristics and participation

Before we evaluate each conference goal, we first describe the conference attendees and their participation in CPIC with data from the conference evaluation forms (see Table 1). Across both conferences, two-thirds (67%) of respondents were administrators, providers, or other staff from community service agencies (including psychologists, licensed therapists and social workers, psychiatrists and other physicians, registered nurses, certified drug treatment counselors, and case managers). Nearly a quarter (23%) were other community members (such as clergy, community advocates, and students), and four percent were academic researchers.

Table 1.

Roles and participation of Community Engagement Conference evaluation respondents.

| Total (n=187) |

South LA Conference (n=109) |

Hollywood/Metro Conference (n=78) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Roles of participants | |||

| Community agency staff | 67% | 64% | 72% |

| Community member at-large | 23% | 25% | 19% |

| Academic | 4% | 4% | 5% |

| Missing/declined to state | 6% | 7% | 4% |

| CPIC study participation | |||

| CPIC Participanta | 55% | 46% | 66% |

| Not currently in CPIC | 29% | 27% | 32% |

| Missing/declined to state | 17% | 28% | 1% |

10% of Hollywood/Metro conference evaluation respondents were CPIC Steering Council members. CPIC Steering Council members were not differentiated on the evaluation forms for the South LA conference.

A little more than half (55%) of conference evaluation form respondents were participants in the CPIC study,28 while a sizable portion (29%) consisted of individuals not affiliated with an organization participating in CPIC at the time of the conference.29 Below, we review findings for each of the three conference implementation goals in turn.

Implementation Goal 1: Stimulating a dialogue, sense of collective efficacy, and opportunities for learning and networking

Analyses of the evaluation form ratings, write-in comments, and observation field notes indicate that the kickoff conferences were effective at engaging the diverse stakeholders attending the events and stimulating at least an initial sense of community and collective efficacy around improving depression care.

Respondents to the overall conference evaluation forms rated the conference highly in terms of general feeling of engagement throughout the event, opportunities to network with other conference participants, and learning from talking and interacting with other attendees (average ratings of approximately 4 on a 5-point scale; see Table 2).30 Even higher overall ratings were reported for feeling more hopeful about the ability of the community to improve depression care—an indicator of collective efficacy. The only marginally significant difference on these measures between the two conferences was for the item on opportunities for networking (p < 0.10), but the ratings for both were still around 4.0 (3.92 vs. 4.13). These results were similar for respondents who were participating in CPIC at the time of the conference as well as those who were not (not shown).31

Table 2.

Mean ratings on General Conference Evaluation Form items related to Goal 1: Stimulating a dialogue, sense of collective efficacy, and opportunities for learning and networking.

|

How much would you agree or disagree

with the following statements a |

Total | South LA | Hollywood/ Metro |

|---|---|---|---|

| I felt engaged throughout conference. | 4.08 (0.722) |

4.09 | 4.07 |

| I had ample opportunities to meet and network with other conference participants. |

4.04 (0.785) |

4.13* | 3.92* |

| I learned a great deal from talking and interacting with other conference participants. |

3.96 (0.806) |

4.05 | 3.85 |

| I feel more hopeful now than before the conference that our community can make progress in improving depression care. |

4.23 (0.754) |

4.26 | 4.21 |

Scale ranged from 1=Disagree Strongly to 5=Agree Strongly.

Mean ratings for this item differed significantly between conferences, p < 0.10.

Note: underlines added for emphasis. Standard deviations shown in parentheses.

The analysis of the evaluation form write-in comments related to Goal 1 of the conference suggested that the level of engagement and dialogue experienced by attendees was associated with themes of openness, friendliness, interactivity, and respect in the atmosphere generated during the conferences, as illustrated in the following examples:

Everyone had the opportunity to express ideas (Hollywood/Metro)

I like that this was an open discussion, question and answers. I like the fact that there weren’t any wrong answers (South LA)

Interactive approach with client/community participation. Warm friendly organizers and speakers (South LA)

The feeling that people were talking, not being talked to (Hollywood/Metro)

A sense of community and collective efficacy was also expressed in write-in comments by a number of respondents that described having formed connections and common cause with others, as well as feeling inspired and hopeful by being part of a larger enterprise. Themes related to community-building in particular centered on “collaborative spirit,” “inclusion,” “networking and learning from each other,” and pooling of strengths, which were evident in comments that respondents wrote on what they liked about the conference:

The unity of all parties. (South LA)

Everyone is here for one cause… (Hollywood/Metro)

The collaboration between all different kinds of agencies and “providers” (Hollywood/Metro)

The wide range of experiences and backgrounds of presenters and attendees. (South LA)

The networking, learning about the study and services available. (South LA)

I think CPIC will create an interactive network that helps my community (Hollywood/Metro)

That it spoke from a strengths-based perspective and it acknowledged that the best way to beat depression is to get the community involved. (South LA)

Themes of collective efficacy were reflected in feelings of hope and desires to make change:

It left me with a sense of hope… the idea of finding community support for addressing depression, it’s not all on my shoulders. (Hollywood/Metro)

Let’s get it on! (South LA)

The community seems to be ready. (South LA)

The observations of conference sessions echoed many of these themes. Both session leaders and conference participants spoke of the need to “work together,” “build a village,” “harness each other’s resources,” and “create bridges for depression care.” Participants were observed to be very interactive and supportive of one another. For example, when a community stakeholder at the Hollywood/Metro conference stated how much he felt on his own in addressing the depression care needs of his clients, a member of the CPIC Steering Council responded “You are not alone.”

Engagement strategies, such as use of personal stories, appeared to elicit attitudes of empowerment and activate participants. As one attendee shared “As a community member, we have a voice. We do not know how loud it is. You can share your depression story with others, so that they can seek help.” Likewise, the seating arrangements and other strategies used to encourage interactions appeared largely to have resulted in the desired mixing, although some clustering among individuals of like backgrounds and previous familiarity was still observed, especially among academic participants.

Comparison of the conference observation notes did reveal a stylistic difference between the group dynamics at the two events which was not anticipated during the efforts to tailor the conference design to the community settings. Attendees at the South LA conference were generally quick to speak up, ask questions, and react to comments of session leaders and other participants. Attendees at the Hollywood/Metro conference appeared more reticent, particularly at the start of the day, although they readily participated when opportunities to do so were explicitly presented. It was not clear how much this difference was due to different levels of prior familiarity among participants or with the community engagement format of the conference in South LA. However, this difference did not appear to prevent either conference from attaining the objective of engaging participants around the issue of depression in the community, as reflected in the conference observations and evaluation form responses.

Implementation Goal 2: Activating interest and participation in the randomized improvement trial

Our quantitative and qualitative evaluation data also provided evidence that the conferences were effective in terms of their second goal, activating interest and participation in the CPIC study. Eighty-nine percent (89%) of respondents on the overall conference evaluation forms agreed or strongly agreed that they would recommend the event to others if held again, an indication of general interest in participating in future CPIC activities (mean rating of 4.28 on a 5-point scale; see Table 3). Respondents similarly perceived the relevance and likely influence of study materials and sessions on their work to be relatively high: mean score of 4.05 on the overall relevance of conference information and materials for their work (see Table 3), and mean scores of between 4.21 and 4.47 on the likelihood that individual breakout sessions will influence their work (see Table 5, second row of results).

Table 3.

Mean ratings on General Conference Evaluation Form items related to Goal 2: Activating interest and participation in the randomized improvement trial.

| Total | South LA | Hollywood/ Metro |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

How much would you agree or disagree

with the following statements a | |||

| I would recommend the event to others if held again. |

4.28 (0.765) |

4.31 | 4.24 |

|

Rate the following educational aspects of

the conference b | |||

| Relevance of information and materials for your work. |

4.05 (0.859) |

3.98 | 4.15 |

Scale ranged from 1=Disagree Strongly to 5=Agree Strongly.

Scale ranged from 1=Poor to 5=Excellent.

Mean ratings for this item differed significantly between conferences, p < 0.10.

Note: Standard deviations shown in parentheses.

Table 5.

Mean ratings on Conference Evaluation Form items for Breakout Sessions on Toolkits and Components of Collaborative Care.a

| Total mean scores (across both conferences) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Medication Management |

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy |

Care Management/ Outreach |

|

|

Indicate the most appropriate rating

for each item below. b |

n=17 | n=53 | n=33 |

| Extent session engaged participants | 4.23 | 4.15 | 4.57 |

| Likelihood the session will influence your work |

4.41 | 4.21 | 4.47 |

| Overall effectiveness of the session | 4.41 | 4.30 | 4.55 |

| Knowledge of the topic BEFORE the session |

3.18 | 3.40 | 3.84 |

| Knowledge of the topic AFTER the session |

4.23 | 4.12 | 4.42 |

Table includes the three breakout sessions that were consistent across both conferences. A fourth breakout session was held at the conferences, but differed in topic.

Scale ranged from 1=Poor to 5=Excellent.

Written responses to the open-ended items on the conference evaluation forms accentuated specific interests of participants with regard to the CPIC study and depression care. We identified three general themes: 1) raised awareness and interest in the issue of depression and/or its effects on the community; 2) raised awareness and interest in the collaborative care model upon which CPIC is based; and 3) stimulated interest and knowledge-seeking about the CPIC study itself and/or research on depression.

In terms of raising awareness or stimulating interest in the issue of depression, various participants noted the “importance of the topic” and “that depression is a serious problem in the community”. Typical of comments related to interest in the collaborative care model, one participant wrote that “I like the overall concept and intent of the conference to address the pervasive needs of mental health with [the] collaborative method.” A number of conference participants explicitly indicated that they wanted to become more involved in CPIC, with a few providing contact information and requests to be contacted. Others expressed interest in results of studies on depression or a desire to seek out additional research findings on depression and how to treat it. Several indicated that they better understood the CPIC study, although one respondent felt that the conference did not provide enough information on “next steps” for the study.

We speculate that some of these results may be attributable to how conference organizers and session leaders were observed to have presented and framed the CPIC study to participants. First, speakers emphasized the long-term benefits of treating depression with evidence-based care: “If you do depression care a little bit better, work using evidence-based toolkits, in interventions after 5 and 10 years, families are staying together and people live normal lives. Doing depression care [even] a little bit better makes a huge difference.” Second, organizers and session leaders also emphasized how the CPIC study’s collaborative model is intended to complement what agencies are currently doing: “Everyone here is doing a great job with the services you provide. We hope this [collaborative care model] will enhance it more. We want to make your job easier.” Third, CPIC study leaders highlighted that all agencies—regardless of the intervention condition into which they were to be randomized—will receive benefits: “Everybody will get something…You will have a lot of resources. It is not a study where some get stuff, others don’t.” A final related observation was that several new participants enrolled in the study directly following the end of the Hollywood/Metro conference.

Implementation Goal 3: Introducing evidence-based toolkits and collaborative care models

With regard to the conference’s third goal of introducing evidence based toolkits and collaborative care models, respondents on the overall evaluation form rated the conference highly on meeting its educational goals, including describing successful service delivery models for depression care, the collaborative care model in particular, as well as explaining the community engagement approach and partnership development as applied to depression care (mean ratings of 3.99 to 4.06 on a 5-point scale; see Table 4).32

Table 4.

Mean ratings on General Conference Evaluation Form items related to Goal 3: Introducing evidence-based toolkits and collaborative care models.

|

Indicate how well this conference addressed

each of its main educational objectives a |

Total | South LA | Hollywood/ Metro |

|---|---|---|---|

| To describe successful service delivery models for depression care. |

3.99 (0.824) |

3.88** | 4 14** |

| To summarize collaborative care models for depression. |

3.99 (0.890) |

3.88* | 4.14* |

| To understand the community engagement approach. |

4.03 (0.905) |

3.96 | 4.12 |

| To understand partnership development in addressing depression. |

4.06 (0.820) |

4.03 | 4.11 |

Scale ranged from 1=Poor to 5=Excellent.

Mean ratings for this item differed significantly between conferences, p < 0.10.

Mean ratings for this item differed significantly between conferences, p < 0.05.

Note: underlines added for emphasis. Standard deviations shown in parentheses.

In addition, the individual breakout sessions that introduced specific evidence-based toolkits and components of the collaborative care model (e.g., Medication Management, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, and Care Management/Outreach) generally were rated as highly effective (mean scores of 4.30 to 4.55; see Table 5), and respondents on average reported their self-perceived knowledge of the respective topics for each session to have increased—most for Medication Management (33%, i.e., 4.23 — 3.18 / 3.18), least for Care Management/Outreach (15%).33

Write-in comments frequently indicated appreciation for the “wealth of information” and resources provided on the toolkits and collaborative care model:

Great info - very thorough for the time allotted. Thanks for disc drive and great book!!! (Hollywood/Metro)

…great educational materials were provided. Thank you! (South LA)

Numerous attendees mentioned that they intended to share toolkits and resources provided at the conference with colleagues at their agencies as well as use them in their own practice with clients. As one participant wrote “I have the tools now to help parents who feel depressed. I can better help them and refer them to other agencies.” Specific tools that respondents intended to use included the PHQ-9 depression screening questionnaire, care management worksheets, and cognitive behavioral therapy:

[N]ow I have CBT forms to use with clients in sessions (CBT)

I will include CBT in group counseling sessions (CBT)

I will educate mothers about depression and how depression can be diagnosed. (Medication Management)

I will be giving this information with our nurse… to enhance the identification and management of our clients experiencing depression. (Medication Management)

I can go back to my center and look at the overall community and guide our patients… on where they can get help and support (Case Management/Outreach)

Key information that respondents felt they learned from the Medication Management sessions included how to detect depressive symptoms, knowledge about anti-depressive medications and managing clients on medication, and the potential benefits of depression care for clients. Key information that respondents reported they learned from the Cognitive Behavioral Therapy sessions included general overviews of CBT’s goals and how it treats depression, and specific CBT strategies and techniques (such as identifying thoughts and “challenging dysfunctional thinking” and its focus on changing behavior). Information considered important from the Care Management/Outreach sessions centered on how to use the care management forms, as well as to identify and manage depressed clients. Some respondents wrote that they would need to adapt the forms for their setting.

These results may reflect how well the evidence-based toolkits and collaborative care models were introduced and the extent to which participants intended to use what was presented, yet they leave open the question of the conferences’ effect on actual practice behavior (to be assessed in subsequent stages of the study evaluation). Pointing toward the latter, respondents to the evaluation forms identified needed supports and potential barriers they perceived would likely affect their use in practice. Needed supports included additional training and supervised practice, longer training sessions, regular training follow-up, and requests for individual agency trainings; training on how to start a dialogue with the community and approach community members’ needs; and more opportunities for networking and getting support from colleagues in regular gatherings. Potential barriers included system-level constraints (e.g., HIPAA liability issues), being able to work out the concerns and ideas of multiple parties, potential in “getting lost” along the way, and being an isolated advocate for change within an agency (e.g., “I can only change the way I do things, my organization works on policy and procedural changes”).

Despite the effectiveness of the sessions in introducing the toolkits and components of collaborative care, the consensus review of observations noted that the conferences, particularly the first one, were less effective at conveying how these constituent elements fit and work together. Without a clear understanding of the central feature of the collaborative care approach utilized in the CPIC study—namely the coordination and communication across providers and agencies to serve the needs of clients—attendees seemed uncertain at times about the design of the CPIC initiative and how (or if) its various pieces cohered. This uncertainty may have been partly due to a lack of sufficient emphasis on the key features and use of the collaborative care model in CPIC, but also to the attention given to the variety of collaborative service delivery approaches in the community and to the relative complexity of the collaborative care model and agency-randomized CPIC trial.

CONCLUSION

Results indicated that this type of community engagement conference was effective at stimulating a collective sense of connection and efficacy, activating interest and participation in the CPIC study, and introducing evidence-based toolkits and collaborative care models among diverse stakeholders for depression care improvement. These results are particularly significant given the great stigma and silence that often surrounds mental health conditions like depression in underserved minority communities.

Conference attendees, including wider community stakeholders not participating in the randomized implementation trial, rated the conference high in terms of satisfaction (e.g., meeting educational objectives), engagement in conference sessions, networking and learning from other attendees, and common cause for improving depression care. Multiple themes across the write-in comments and observation notes indicated attendees felt a sense of being interactive and connected with each other and inspired to make a difference around depression care. Less evident was a clear understanding of the study design and collaborative care models, although this appeared to improve from the first to the second conference.

The breakout sessions—which focused on distinct components of collaborative care for depression, such as medication management, care management, and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)—generally succeeded in introducing and generating enthusiasm for implementing these elements, but also identified the need for a variety of supports, such as additional intensive trainings, as well as potential barriers, such as limited ability of individuals to effect change within their own agencies and difficulty in reaching consensus across such diverse organizations.

Lessons learned included the usefulness of opening the conference to a wider community audience (i.e., beyond formal participants in the randomized agency trial) to broaden the base of input and support of the initiative in the community, and the necessity of spending the time to adequately engage participants and develop common visions of action before expecting to embark on detailed community planning and implementation tasks in a community-partnered initiative. We also learned that, although it may not be possible to anticipate all differences in community dynamics and approaches to health concerns, attending to these features is important in being able to effectively frame mental health issues and engage stakeholders in specific communities around a highly stigmatized illness such as depression.

Limitations of the analyses reported here include that many of the data are based on the conference evaluation forms which, although anonymous, may be subject to social desirability bias. This is one reason we gathered extensive field notes of conference activities, in order to supplement the self-reported data with documentation of observed behavior and discourse. This evaluation is also limited in the extent to which it can differentiate the effects of these particular conferences from previous community engagement activities that attendees may have experienced, given that we do not have consistent data on the latter for all participants. This issue may be particularly relevant for the South LA conference, since the main CPIC community partner in that area has been a pioneer in the community engagement model adapted for the CPIC study. In one sense, however, the Hollywood/Metro conference represents a test of whether the model could be adapted and replicated in another community with different sets of participants and stakeholder experiences. The results from these analyses suggest that it was possible.

Similarly, the analyses presented here are not able to disentangle which components of the conferences are necessary or sufficient “core” features of the intervention for obtaining some minimum level of engagement. We provide detailed descriptions of the range of features and the rationales for their incorporation into the “kickoff” conferences. However, it would likely take systematic variation of designs across a larger number of conference events to more confidently assess the relative effects of specific features.

Lastly, the scope of these analyses is limited to the immediate effects and perceptions of the conferences in engaging participants. Although we present various results of the degree to which participants felt or were observed to be engaged in the conference itself, their reported intentions to use the project toolkits and care models, and their indication of interest to further participate in the study, the ultimate objectives of the CPIC study are to examine whether the community engagement process continues, particularly in the CEP arm, and whether it makes a difference in the ability of community agencies and stakeholders to improve care and outcomes for depressed individuals. However, in order to evaluate this chain of effects and the contribution of the “kickoff” conference, it is first necessary—as we do in this paper—to assess if this initiation event was indeed engaging and in what ways.

In particular, whether a sustainable “village” or community-of-practice around depression care improvement develops in the Community Engagement and Planning (CEP) or Resources for Services (RS) condition of the CPIC study is for later phases of the study evaluation to assess. But the findings presented here demonstrate it was possible to initiate these processes at the “kickoff” of the project through such a conference, which represents one intervention in the community engagement tool box. We expect that the lessons learned in doing so will be applicable to studies founded on community-partnered principles as well as other types of community-based studies more generally.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by Community Partners in Care (NIH/NIMH grants R01MH78853, R01MH78853S1); Partnered Research Center on Quality Care (NIH/NIMH grant 1P30MH082760-01); Charles R. Drew University/University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) Project EXPORT (NIH/NCMHD grants MD00148, MD00182); Research Center in Minority Institutions (NIH/NCRR grant 1U54RR022762-01A1); Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (grant 64244); RAND Health; QueensCare Health and Faith Partnership; COPE Health Solutions; and Healthy African American Families II.

The authors would like to acknowledge Ken Wells (UCLA/RAND) and Loretta Jones (Healthy African American Families) for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper, and other members of the CPIC Steering Council for their contributions to the community conferences and feedback to the preliminary analyses for this paper: James Gilmore (Behavioral Health Services); Franz Jordan (Children’s Bureau, Inc.); Angela Young-Brinn (Healthy African American Families); Cheryl Branch (HOPICS); Vivian Sauer (Jewish Family Services Los Angeles); Wayne Aoki (Los Angeles Christian Health Centers); Staci Atkins, Edward Vidaurri, Yolanda Whittington (Los Angeles County of Department of Mental Health); D’Ann Morris (Los Angeles Urban League); Nancy Carter, Lynn Goodloe (National Alliance for the Mentally Ill / Urban Los Angeles); David Chambers (National Institute of Mental Health); Nomsa Khalfani (St. John’s Well Child & Family Center); Thomas Belin, Bowen Chung, Susan Hirsch, Craig Landry, Jeanne Miranda, Michael Ong, Esmeralda Ramos, Susan Stockdale, Lingqi Tang (University of California, Los Angeles); Mariana Horta, Emily Cansler, Rick Garvey, Belle Griffin, Paul Koegel, Judy Perlman, Cathy Sherbourne, Aziza Wright (RAND Corporation).

The authors also would like to thank Norma Mtume (Shields for Families), David Martins, MD (UCLA and Drew University), and Judy Ho, PhD (UCLA) for leading sessions, and the many other community and academic participants at the CPIC kickoff community conferences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jones L, Koegel P, Wells KB. Bringing experimental design to community-partnered participatory research. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007;297:407–410. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallerstein N. Commentary: challenges for the field in overcoming disparities through a CBPR approach. Ethn Dis. 2006 Winter;16(1 Suppl 1):S146–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones L, Wells K, Norris K, Meade B, Koegel P. Chapter 1. The Vision, Valley, and Victory of Community Engagement. Ethn Dis. 2009a Autumn;19(1 Suppl 6):S3–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones L, Meade B, Forge N, Moini M, Jones F, Terry C, Norris K. Chapter 2. Begin Your Partnership: The Process of Engagement. Ethn Dis. 2009b Autumn;19(1 Suppl 6):S8–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moini M, Fackler-Lowrie N, Jones L. Community engagement: Moving from community involvement to community engagement—A paradigm shift. PHP Consulting; Santa Monica, Calif: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khodyakov D, Mendel P, Dixon E, Jones A, Masongsong Z, Wells K. Community Partners in Care: Leveraging Community Diversity to Improve Depression Care for Underserved Populations. International Journal of Diversity in Organizations, Communities and Nations. 2009;9(2):167–182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung B, Jones L, Jones A, Corbett CE, Booker T, Wells KB, Collins B. Using community arts events to enhance collective efficacy and community engagement to address depression in an African American community. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(2):237–244. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.141408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carroll JM, Rosson MB, Zhou J. Collective efficacy as a measure of community; Paper presented at CHI 2005, Papers: Large Communities; Portland Oregon. 2005.Apr 2-7, [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bandura A. Exercise of human agency through collective efficacy. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2000;9:75–78. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sampson RJ. The neighborhood context of well-being. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 2003;46(3):S53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sampson RJ, Raudenbush S, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277(15 August):918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown JS, Duguid P. Organizational learning and communities of practice: Toward a unified view of working, learning, and innovation. Organization Science. 1991;2(1):40–57. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wenger E. Communities of Practice. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lave J, Wenger E. Situated Learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wenger E, Snyder WM. Communities of practice: The organizational frontier. Harvard Business Review. 2000;78(1):139–145. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mendel P. Organizational learning and sustained improvement: The quality journey at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. In: Bate SP, Mendel P, Robert G, editors. Organizing for quality: Journeys of improvement at leading hospitals and health care systems in Europe and the United States. Radcliffe Publishers; Oxford: 2008. pp. 57–82. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castaneda H, Nichter M, Muramoto M. Enabling and Sustaining the Activities of Lay Health Influencers: Lessons from a Community-Based Tobacco Cessation Intervention Study. Health Promotion Practice. 2008 Jun 6; doi: 10.1177/1524839908318288. online first. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bate SP, Robert G. Knowledge management and communities of practice in the private sector: Lessons for modernizing the National Health Service in England and Wales. Public Administration. 2002;80(4):643–63. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hope A, Timmel S. Training for transformation: A handbook for community workers. ITDG Publishing; Books I-IV. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mendel P, Meredith LS, Schoenbaum M, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. Interventions in organizational and community context: A framework for building evidence on dissemination and implementation in health services research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research (APMH & MHSR) 2008;35(1-2):21–37. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0144-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schoenwald SK, Hoagwood K. Effectiveness, transportability, and dissemination of interventions: What matters when? Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:1190–1197. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.9.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chung B, Dixon E, Jones L, Miranda J, Wells KB, Community Partners in Care Steering Council Using a community partnered participatory research approach to implement a randomized controlled trial: Planning the design of Community Partners in Care to improve the fit with the community. Journal of Healthcare for the Poor and Underserved. 2010;21(3):780–95. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The fourth afternoon session differed in topic between the two conferences (in South LA, it focused on Team Leadership for collaborative care and service improvement; in the Hollywood/Metro conference, the fourth session discussed the various support resources provided to agencies by the CPIC project).

- 25.Open-ended evaluation form questions for the conference in general included “What did you particularly LIKE about this conference?,” “How will use what you learned today?,” and “What changes for future conferences, or any additional comments, would you suggest?” Open-ended questions on the evaluation forms for the individual afternoon breakout sessions included “What was the most important information that you learned from this session?,” “How will you change the work that you or your organization does based on the information from this session?,” and “Please provide any additional comments about this session.”

- 26.The overall conference evaluation questionnaire response rate was 61% for the South LA conference, and 57% for the Hollywood/Metro conference.

- 27.This session also had the largest attendance for an afternoon breakout session at either conference (64 attendees).

- 28.These CPIC participants included both CPIC Steering Council members who organized the conference, and participants from agencies enrolled in the study’s randomized implementation trial. 10% (i.e., 8 out 78) of Hollywood/Metro conference evaluation respondents were CPIC Steering Council members. CPIC Steering Council members were not differentiated from CPIC implementation trial participants on the evaluation forms for the South LA conference.

- 29.Information on race/ethnicity and gender were not collected as part of either conference registration or evaluation forms.

- 30.Reported levels of engagement were similar for the afternoon breakout sessions (see first row of results in Table 5).

- 31.Other analyses (not presented) which separated CPIC Steering Council members from other CPIC participants for the Hollywood/Metro conference (the only conference evaluation form that distinguished the two) showed CPIC Steering Council members to rate the conference slightly higher on these measures, but differences were only statistically significant for the item on having ample networking opportunities (p < 0.10), and the mean ratings for the other CPIC participants still remained near 4.0 out of the 5-point scale (ranging from 3.80 for learning from other conference participants to 4.15 for being more hopeful that the community can improve depression care).

- 32.Mean ratings between the conferences were statistically different for describing successful service delivery models (p < 0.10) and summarizing collaborative care models for depression (p < 0.05). But the ratings for both conferences were still around 4.0 (3.88 vs. 4.14).

- 33.However, it should be noted that these ratings are based on self-perceived levels of knowledge (as opposed to tests of specific knowledge) and the rating of the “before” knowledge is actually measured after the session (which may introduce a retrospective bias).