Abstract

The effective dissemination and implementation of evidence-based health interventions within community settings is an important cornerstone to expanding the availability of quality health and mental health services. Yet it has proven a challenging task for both research and community stakeholders. This paper presents the current framework developed by the UCLA/RAND NIMH Center to address this research-to-practice gap by: 1) providing a theoretically-grounded understanding of the multi-layered nature of community and healthcare contexts and the mechanisms by which new practices and programs diffuse within these settings; 2) distinguishing among key components of the diffusion process—including contextual factors, adoption, implementation, and sustainment of interventions—showing how evaluation of each is necessary to explain the course of dissemination and outcomes for individual and organizational stakeholders; 3) facilitating the identification of new strategies for adapting, disseminating, and implementing relatively complex, evidence-based healthcare and improvement interventions, particularly using a community-based, participatory approach; and 4) enhancing the ability to meaningfully generalize findings across varied interventions and settings to build an evidence base on successful dissemination and implementation strategies.

Keywords: dissemination, diffusion, implementation, organizational context, community-based research, evidence-based interventions

1. Introduction

The growing concern with implementation and dissemination within health services (NIH 2006a, 2006b; Implementation Science 2006) is a natural consequence of the well-publicized “gap” between research and practice, and the continued difficulty in extending health and mental health treatments with proven efficacy into community-based settings of care (Glasgow, Lichtenstein, and Marcus 2003; Lenfant 2003; IOM 1998; HHS 1999).

This gap has forced many researchers and other stakeholders in health systems to grapple with the varied nature of healthcare and community settings, and the processes at play in translating and implementing evidence-based practices into these contexts. Researchers venturing into these areas quickly confront a series of common issues, including how to translate interventions to encourage uptake and implementation in ways that preserve scientifically validated components of evidence-based practices, how to obtain buy-in of various stakeholders in settings over which researchers have little control, and how to sustain interventions beyond initial demonstrations and funding, particularly in settings with highly constrained resources (Schoenwald and Hoagwood 2001; Hohmann and Shear 2002; Mueser et al. 2003).

Research on healthcare and community contexts and their role in the dissemination of evidence-based health interventions remains relatively nascent (Glisson and Schoenwald 2005). Yet, as emphasized in reports by the Institute of Medicine (IOM 2000) and National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH 2000), a number of fields outside of health and mental health services offer an abundance of applicable concepts and findings on topics such as the diffusion of innovations, organizational and community development, and social and behavioral change.

This paper describes the research questions and challenges that have arisen in the efforts by the UCLA/RAND NIMH Center for Research on Quality in Managed Care to address these issues and the progressive succession of approaches taken by the center to study organizational contexts in healthcare and community settings. These approaches have ranged from crude measures in traditional intervention studies, to exploration of community-based participatory research methods, to the development of a conceptual framework of dissemination based on both the review of wider social science literatures and the specific experiences of center investigators and community partners. The latter portion of the paper presents this current, and evolving, framework and its intended objectives, including how it is being used to help guide and generalize across a variety of ongoing projects.

2. Studying Interventions in Context: Research Questions and Approaches

The UCLA/RAND Center, first funded in 1995 by the National Institute of Mental Health, is a joint program of the UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute and RAND Health in Santa Monica, California that bridges public policy and clinical services research to study mental health and related care for vulnerable populations. Although the center’s projects are, as with any research program, undoubtedly unique, its experiences have raised a number of general research questions, as well as limitations of conventional approaches, in attempting to improve community-based dissemination and implementation in health services.

Several early, innovative randomized studies that center investigators participated in, such as the RAND Health Insurance Experiment (Wells et al. 1989) and the Medical Outcomes Study (Wells et al. 1996), took into account general system of care indicators—for example, managed care versus fee-for-service reimbursement systems. This type of research design roughly differentiated incentives facing providers, but did not (nor was intended to) measure implementation in terms of organizational and practice-level changes, how these might have explained differences in outcomes, or the likelihood of sustaining outcomes over time.

A few more recent studies, such as the Health Care for Communities project, have usefully characterized community risk factors for need and unmet need related to alcohol, drug abuse, and mental health conditions (Sturm et al. 1999; Young et al. 2001), yet have been less clear in answering the next logical question, namely how to redress unmet needs and identify or develop interventions to improve the quality of local services in particular communities.

Other studies generated within the center, however, have actively developed a range of quality improvement (QI) interventions for highly prevalent mental health conditions in settings accessible to vulnerable populations. It is here where the “gaps” between research and practice have been most evident—and frustrating.

For example, the Partners in Care (Wells et al. 2000), Youth Partners in Care (Asarnow et al. 2005), and Project IMPACT (Unützer et al. 2002) studies have been generally successful in demonstrating the clinical and cost effectiveness of QI interventions for depression treatment in primary care settings for adults, adolescents, and elderly patients, respectively. Yet the interventions reached only a fraction of all eligible patients. Moreover, while establishing effective models of care, the studies have largely been silent on how to assure the sustainability of these relatively complex, multi-modal interventions involving multiple stakeholders or their further adoption in other locales and systems of care.

These and other center studies, such as the Caring for California’s Children Initiative (Zima et al. 2005), have also included a variety of indicators of organizational capacity for QI obtained through administrator interviews, provider surveys, computerized collection of service data, and other means. While this information has yielded useful insights into implementation issues (Rubenstein et al. 1999; Meredith et al. 1999, 2001), the measures incorporated were typically based more on practical experience than conceptual understanding, and have proved difficult to use in unpacking the implementation and dissemination process, linking those to intervention outcomes, and generalizing findings across studies.

As a consequence, the center’s goals expanded to include an emphasis on dissemination (i.e., the targeted distribution of information on evidence-based health interventions) and implementation (i.e., the adaptation and putting into practice of such interventions over time) within community and healthcare settings (Lomas 1993; Fixsen et al. 2005). A distinctive approach resulting from this new emphasis has been the center’s effort to engage multiple community stakeholders in the design, dissemination, and implementation of health interventions. Termed “community-partnered participatory research” (Jones and Wells 2007; Wells et al. 2004), examples of such initiatives include Witness for Wellness—a multi-stakeholder, academic-community partnership aimed at improving health and other outcomes related to depression in minority communities (Bluthenthal et al. 2006; Stockdale, Patel, et al. 2006; Jones et al. 2006; Chung et al. 2006), Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (or CBITS)—a school-based collaborative project, now extended to a faith-based community health partnership, to provide mental health screening and standardized brief cognitive behavioral therapy treatment for youth exposed to violence (Kataoka et al. 2006), and the Health Care for Communities (HCC) Partnership Initiative—a collaboration with several community partners to assess organizational capacity and interest in partnering among local agencies around mental health and substance abuse needs (Stockdale, Mendel et al. 2006).

As the center has moved toward working more closely with stakeholders in “real world” community settings (e.g., primary care practices, workplaces, community-based organizations, local service organizations), we have recognized the need, as have others (Grimshaw et al. 2004; Shojania and Grimshaw 2005; ICEBeRG 2006), for conceptual models of dissemination, implementation, and sustainability within these contexts in order to help guide and compare results over such varied settings and initiatives.

Beginning in the next section, we present the framework we have developed, illustrated with examples from the Witness for Wellness, CBITS, Partnership Initiative, and other center studies. We view this guiding framework as a necessarily evolving project, as our initial multi-disciplinary integration of social science research meets with ongoing community-based intervention experience and the application of additional concepts over time. The current framework is specifically intended to help answer the following questions that have arisen during our attempts to study and close the research-to-practice gap:

How best to understand and assess the relevant contextual factors and dynamics affecting the dissemination, implementation, and sustainability of interventions within community and healthcare settings

How to effectively identify, develop, and evaluate new strategies for tailoring, disseminating, and implementing relatively complex interventions across a variety of healthcare and community stakeholders and contexts

How to provide useful formative feedback to investigators and other partners to guide the dissemination and implementation of interventions without jeopardizing evaluation objectives

How to build capacity among academic and other stakeholders both for dissemination and evaluation of interventions in healthcare and community settings

How to meaningfully generalize findings and pool results across varied dissemination and implementation studies

3. Multiple Stakeholders and Levels of Community and Healthcare Settings

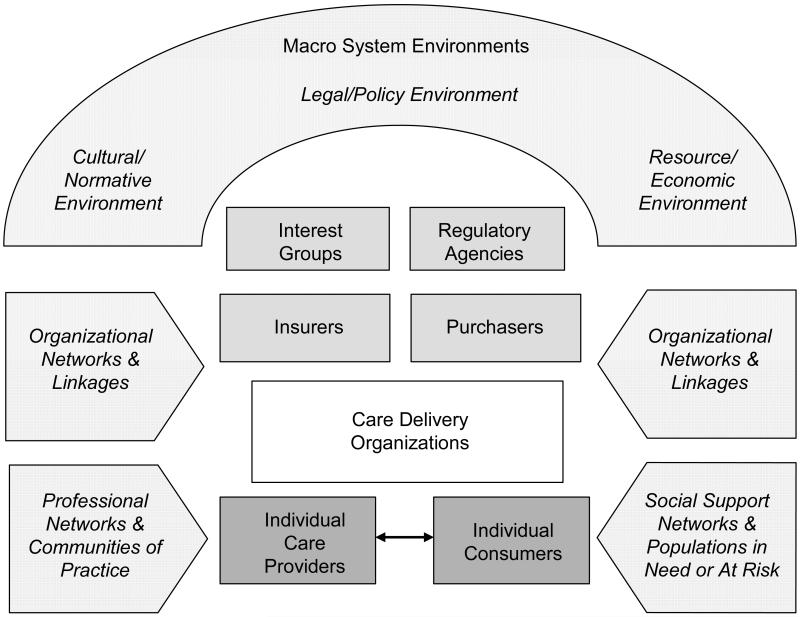

Figure 1 introduces a general depiction of community healthcare contexts. A “community” refers to a group of people or organizations defined by function (such as an industry), geography (such as a metropolitan area), shared interests or characteristics (such as ethnicity, sexual orientation or occupation), or by a combination of these dimensions (Fellin 1995; Scott 1994), in which members share some sense of identity or connection (Schulz, Israel and Lantz 2003; DiMaggio and Powell 1983). Here we specify a community in terms of stakeholders in the provision and receipt of health care within a bounded, geographic area in order to emphasize capacity building (Jones and Wells 2007) and processes of “collective efficacy” (Sampson 2003; Sampson, Raudenbush and Earls 1997) that facilitate action at the local level.

Figure 1. Multiple Stakeholders and Levels of Community Healthcare Settings.

Typically, health intervention strategies focus on consumers of care, individual care providers, or their points of interaction (bottom of Figure 1). However, consumers and providers exist within social contexts that structure, enable, and constrain their behavior. In particular, they tend to interact within organized settings that exhibit their own collective norms and sets of routines and policies, whether conventional health services or other types of organizations, such as schools, churches, or social service agencies. Outside of these settings, consumers are also embedded in networks of social relationships and systems of support (e.g., family, friends, and various relations) that influence health behavior, decisions, and the seeking out of healthcare (Pescosolido et al. 1998; Cohen and Syme 1985). Similarly, care providers often have ties to networks of professionals and “communities of practice” that promote identification with common goals and sharing of knowledge (Bate and Robert 2002; Brown and Duguid 1991).

Figure 1 further illustrates the multi-level composition of communities. Stakeholders are nested in the sense that care delivery organizations comprise an important context for consumers and care providers. In turn, insurers and employers, as well as regulators and interest or advocacy groups, comprise important elements of the context for service organizations, providers and consumers. And all are embedded within overarching cultural, legal, and resource environments (Scott et al. 2000).

The main purpose of this basic depiction is to serve as a reminder that interventions may be directed at different levels of healthcare and community systems. As we describe below, this fact has implications for the types of stakeholders and dissemination or implementation strategies appropriate for particular interventions. A system-wide perspective also helps to identify potential unintended effects on other parts of healthcare and community systems and focus attention on how interventions at different levels of the system may work in conjunction or at cross-purposes. Such a multi-level approach is recommended for quality improvement in complex systems (Wagner et al. 1996; Ferlie and Shortell 2001), but less frequently represented are grass-roots community levels that are especially pertinent to interventions designed to address health disparities (IOM 2000). Our “community-partnered” perspective seeks to integrate these approaches, a process which requires blending strategies and negotiating priorities between traditional, research-oriented QI and community-based, participatory perspectives (Wells et al. 2004; Stockdale, Patel et al. 2006).

4. Framework of Dissemination in Healthcare Intervention Research

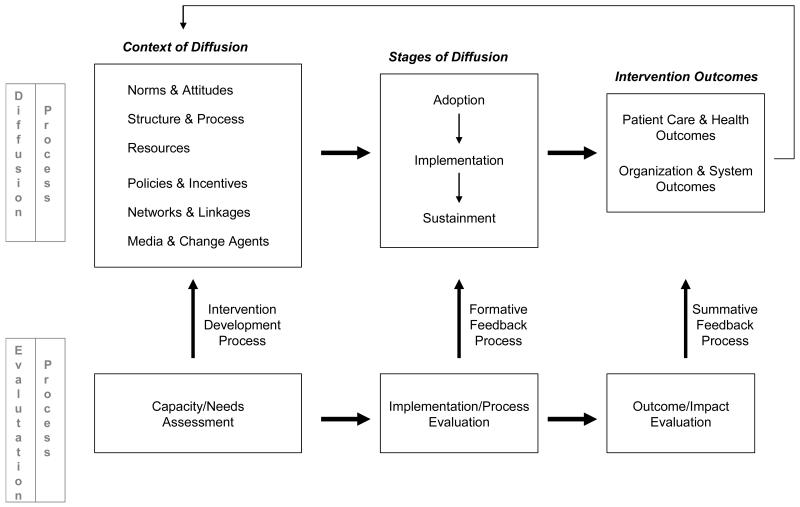

It would be difficult—if not impossible—for any single theory to capture the dynamics of disseminating interventions within complex contexts, such as healthcare and community settings. Consequently, our framework presented in Figure 2 is not itself a theory, but draws concepts and insights from multiple research perspectives to identify general factors and key processes in the dissemination and evaluation of health interventions.

Figure 2. Framework of Dissemination in Health Services Intervention Research.

From psychology, we look to social cognitive, learning, and related theories (e.g., Bandura 1977, 2001; Azjen and Fishbein 1980) to understand determinants of individual and group behavioral change. We rely on the organizations and social movement literatures in sociology to identify key collective characteristics and processes in the spread of new practices and the mobilization of people and resources for social and organizational change (e.g., Davis et al., 2005; Strang and Soule, 1998). From economics, we draw from agency theory and related concepts that emphasize the effects of incentives on individual and organizational behavior (e.g., Laffont and Martimort 2002; Williamson 1994). And we use diffusion of innovation theory—which itself has emerged from a variety of disciplines—to understand the process of implementation and the characteristics of interventions that promote adoption and sustainability (e.g., Rogers 2003; Van de Ven et al. 1999; Valente 1995). Where possible, we also employ application of these concepts and evidence generated specifically in health services research (e.g,. Greenhalgh et al. 2004; Rubenstein et al. 2000; Bate, Robert, and Bevan, 2004).

The framework first outlines the diffusion process, from (1) contextual factors affecting diffusion, to (2) the major stages of diffusion broadly defined, and (3) ultimate outcomes. The framework then distinguishes types of evaluation applicable to each of these components (bottom row of Figure 2) and points of connection between the diffusion and evaluation process (as shown by the upward arrows).

4.1. Diffusion Process

Despite the loose definitions found in various studies, the term diffusion generally refers to the spread and use of new ideas, behaviors, practices, or organizational forms, which may include unplanned or spontaneous spread, as well as dissemination—i.e., as described earlier—targeted, directed or assisted diffusion (Rogers 2003). The diffusion process outlined on the top of Figure 2 thus applies whether researchers (academic or community) are actively engaged in dissemination of an intervention, or assume a primarily observational stance.

4.1.1. Contextual Factors

Research on organizational change and diffusion has emphasized the pivotal role of context in conditioning the spread and sustainability of new practices (Strang and Soule 1998), and in determining antecedents and readiness for change in adopting health service innovations in particular (Greenhalgh et al. 2004). Our framework distinguishes six broad sets of contextual factors that are applicable to stakeholders across various levels of communities.

The first three sets of contextual factors—norms and attitudes, organizational structure and process, and resources—address the willingness and ability of stakeholders to implement and maintain new interventions.

Norms & attitudes

This domain encompasses a range of attitudes and knowledge about particular health conditions, expectations and priorities toward types of treatments or client populations, and collectively held beliefs and values that may affect the receptivity of individual and organizational stakeholders to adopt or adhere to a new care practice or intervention. Principles of social cognitive, motivation expectancy, and other social learning theories (Bandura 2001, 1977; Vroom 1964; Maiman and Becker 1974; Ajzen and Fishbein 1980) suggest that such attitudes, knowledge, and priorities affect the value placed on a problem (such as a particular health condition in the community), the perception that taking action will make a difference (i.e., self-efficacy in addressing a problem), and that taking a specific action (such as a QI initiative) will result in a desired outcome (e.g., improving community access to quality healthcare services), all of which influences motivation and success in adopting a new practice or program (Lin et al. 2005). Our efforts to build lasting networks of relationships among academic and community stakeholders through individual projects as well as our wider Community Health Improvement Collaborative (Wells et al. 2006) are specifically aimed at enhancing this type of efficacy at the community level, which depends on both mutual trust and a willingness to intervene for the common good (Sampson 2003; Sampson, Raudenbush, and Earls 1997).

In contrast, the extent to which a group shares certain pejorative associations toward a specific disease—such as described by participants at the Witness for Wellness kick-off conference when asked “What does depression look like?” and “Why is it so hard to talk about?” (Bluthenthal et al. 2006)—will reflect a collective stigma that affects whether and how individuals seek care and how communities, organizations and their members prioritize and deliver care to persons with this condition (Pescosolido, Boyer, and Lubell 1999).

Within service agencies, “organizational climate” consisting of attitudes toward the work environment and job satisfaction (Glisson and James 2002) and perceived organizational support for quality improvement (Shortell et al. 2004) have been shown to affect team performance and successful implementation. Similarly, general dimensions of “organizational culture” reflecting shared norms and values, such as risk-taking, group commitment, and patient-centeredness have been associated with receptivity to organizational change, innovation, and quality improvement (Shortell et al. 2000, 2004). In our community-partnered efforts, these types of norms and attitudes have been evident in the differing working assumptions, associated language, and other clashes in institutional cultures between academics and community members (Jones and Wells 2007; Bluthenthal et al. 2006; Stockdale, Patel et al. 2006). Similarly, the Partnership Initiative observed that some agencies appear more outward and community-oriented than others, raising concerns for how to engage ones less so inclined (Mendel and Fuentes 2006).

Organizational structure & process

This set of contextual factors relates to the structure and way an organization operates, including differences in mission, size, decision-making process, and services offered. Studies of organizational diffusion have shown that organizational attributes such as larger size and greater differentiation in personnel and structure are associated with adoption of new organizational forms (Burns and Wholey 1993; Scott 2001). However, all organizations are generally prone to inertia, especially in their core technical processes (Hannan and Freeman 1984, 1989). In healthcare, this core technology consists of medical knowledge and the routines and procedures that comprise the process of care—from disease detection, assessment and treatment, to subsequent follow-up and prevention (Rubenstein et al. 2000).

How well a quality improvement initiative fits with (or requires changes to) current processes of care may result in ease (or difficulty) in implementing the intervention. For example, in the adaptation of CBITS to a church school and community, the unfamiliarity of the school administration with participating in a research study and of the health service partner with providing mental health services created a variety of logistical challenges, at the same time that use of the school’s existing student counseling and parent education programs greatly assisted implementation (Kataoka et al. 2006).

Resources

Even if key stakeholders are predisposed—both culturally and structurally—toward new programs or practices, analyses of social movement processes outside and within healthcare point to the need to effectively marshal resources in order to spread and sustain wide-scale, systemic change (McAdam, McCarthy, and Zald 1996; Bate, Robert, and Bevan, 2004). Such “resource mobilization” includes varied forms of financial, human, social, and political capital, either from within organizational settings or from the wider environment (Ganz 2000; McCarthy and Zald 1977).

In addition to the typical resources required of clinical health interventions—such as funding for dedicated tasks (care or data management), staff with particular expertise (clinical specialists), and infrastructure (information technology, office space) (Cain and Mittman 2002)—community-partnered projects rely on a range of other “strengths” possessed by community organizations and service providers, including sets of referral relationships, skills in organizing community interests, and not least, the time, effort, and commitment of community members, much of which is volunteered without reimbursement (Bluthenthal et al. 2006; Stockdale, Patel, et al. 2006; Kataoka et al. 2006).

The remaining three sets of contextual factors—policies and incentives, networks and linkages, and media and change agents—represent sources of information and influence through which potential adopters learn about and assess innovations. These sources not only offer inspiration in the form of new ideas, but also guidance in prioritizing the many innovations available at any given time and ongoing reinforcement for previously adopted interventions.

Policies & incentives

This domain relates to incentives (or disincentives) embedded in regulatory policies, funding and reimbursement programs, and rules and policies of adopting organizations themselves that alter the costs and benefits supporting new behaviors and practices. Incentives may be monetary or come in non-financial forms (NHCPI 2002), such as intrinsic rewards or burden of learning new skills, more or less pleasant work environments, and individual or organizational reputation (Weick 1979; Schrum and Wuthnow 1988). From the perspective of economics, stakeholders are likely to implement a particular intervention if they perceive the expected benefits to exceed the expected costs, i.e., when there is a “business case” for quality improvement (Schoenbaum et al. 2004; Leatherman et al. 2003).

The issue of incentives frequently arises when interests of different groups are not aligned, creating a “principal-agent” problem (Laffont and Martimort 2002), such as health plans wishing to increase quality of care and/or reduce costs through service improvements and providers who must bear the costs and typically realize only modest, if any, savings. In this case, the “principal” (i.e., health plan) may seek mechanisms to incentivize the “agents” (i.e., providers), for example, through a pay-for-performance program. However, these mechanisms may in themselves incur various “transaction costs” related to monitoring performance, enforcing rules, and managing the meting of rewards or penalties (Williamson 1994).

In our community-partnered approach, the “business case” for community health interventions has been expressed through the principle of mutual benefit, i.e., explicitly finding and ensuring the “win-win” for all participants from the outset of a project (Jones and Wells 2007). Many of our projects have also emphasized changing the wider system-level policies and incentives that face health services organizations and other community stakeholders. For example, the Partnership Initiative identified disincentives produced by categorical funding restrictions as a major obstacle to coordination among community agencies, and raised the need for partnerships focused on collectively lobbying to effect changes in such policies (Mendel and Fuentes 2006; Mendel 2006). The Witness for Wellness initiative, through its Supporting Wellness workgroup, has gone even further in exploring ways to affect public policies related to the impact of depression on the community through such activities as advocacy with local government agencies and political officials (Stockdale, Patel, et al. 2006).

Networks & linkages

This contextual dimension includes the linkages and connections among organizations and other stakeholders that enable social support and flows of information within a community or healthcare system. Studies utilizing network analysis have developed a body of concepts, tools, and evidence specifically examining how the structure of social relations and patterns of interaction among organizations and individuals provide conduits along which new practices flow (Luke and Harris 2007; Valente 1995).

For example, people tend to associate with and emulate others whom they consider similar to themselves, a principle known as homophily (McPherson, Smith-Lovin, and Cook 2001). Social actors in a community also tend to model the behavior of others located in central positions within a network (Galaskiewiecz 1985), such as those considered to have high status, reputation, or prestige (Podolny 1993; Haveman 1993; Kimberly 1984). These findings are similar to research on the diffusion of medical innovations that emphasize the impact of initial adoption by “opinion leaders” (Soumerai et al. 1998; Lomas et al. 1991; Coleman, Katz and Menzel 1966). Peripheral actors may be among the first to try a new, unproven innovation, but adoption by core members will increase rates of diffusion throughout a network (Pastor, Meindl, and Hunt 1998).

As mentioned above, we have paid substantial attention to developing and managing the networks of relationships among center partners (Wells et al. 2006). In addition, our Partnership Initiative has focused on mapping collaborative networks among agencies in the wider community, viewing these collaborative relationships and experiences as key strengths of local systems in addressing the needs of individuals with mental health and substance abuse disorders (Stockdale, Mendel, et al. 2006). These mappings have provided a unique “community perspective” not always obvious to local community members or academics, and a stimulus for discussion and action, such as around the limited extent of collaborative networks for co-occurring disorders (Mendel 2006; Mendel and Fuentes 2006).

Media & change agents

While potential adopters of interventions are best characterized as active participants in the processes of diffusion, so too are external sources of information and influence on innovative practices. Media outlets—print or electronic—broadcast to audiences that cut across local networks of direct relationships (Strang and Meyer 1993) and play a crucial role in amplifying and editing the diffusion of ideas and specific programs for organizational improvement and reform (Abrahamson and Fairchild 1999).

Moreover, a host of “change agents”—consultants, professional associations, public health officials, therapeutic companies and other marketers of health service interventions—use these media and other methods to actively promote particular innovations and initiatives (Van den Bulte and Lilien 2001; Peay and Peay 1988). These “purveyors” of interventions (Fixsen et al. 2005) also include academics. A distinctive feature of community-partnered research is to bring community experts into the cadre of change agents working to disseminate evidence-based health interventions (Wells et al. 2004; Jones and Wells 2007).

The effective influence of these external sources depends not only on their ability to frame innovations in ways that resonate with the norms, interests, and world views of potential adopters (Benford and Snow 2000), but also their perceived credibility and expertise. Thus, the legitimacy of any specific source may vary across stakeholders, and stakeholder groups may be attuned to different media and types of change agents (Scott, Mendel, and Pollack, forthcoming; Scott et al 2000). For instance, the CBITS program utilized outreach by the school principal to parents and educational skits by young Latino research assistants to students in order to discuss issues of violence and explain the research study (Kataoka et al. 2006). In the Witness for Wellness initiative, the primary focus of the Talking Wellness workgroup has been on evaluating the use of various media including poetry, film, and photography to adapt depression-related initiatives and public health messages, as well as engage the wider community in two-way discussions about the impact of the disease on the community (Chung et al. 2006).

4.1.2. Stages of Diffusion

Much of diffusion research has focused on how contextual factors affect adoption or “uptake”, i.e., the initial decision in more or less formal terms to adopt a new model or intervention. Rogers (2003) notes that the process leading up to this decision is in fact comprised of several phases, including learning about, forming an opinion about, and choosing to reject or adopt the innovation. He also notes that early adopters tend to have different characteristics than middle or late adopters, such as having wider interpersonal networks, higher degrees of mass media exposure, and higher propensities for risk-taking.

In addition to influencing initial adoption, contextual factors affect the implementation of an innovation in practice and whether it is sustained over time. Implementation or “program installation” (see Fixsen et al. 2005) in terms of how a new intervention is configured, used, and adapted (or not) within a setting also tends to proceed in multiple phases, often in a non-linear, stop-start-and-replay fashion (Van de Ven et al. 1999). Sustainability of new health service interventions is, as noted above, one of the central, and most exasperating, issues in bridging the research-to-practice gap.

These broad stages of diffusion follow a roughly sequential order, so that the timing and rate of adoption (i.e., at what point in the lifecycle of the innovation an organization or individual adopts) affects variation in implementation, or how the innovation is configured and used (Westphal, Gulati and Shortell 1997; Tolbert and Zucker 1983). In turn, variations in implementation affect the sustainment of innovations, in terms of the persistence of program structures, duration of new care practices, and continued spread to other potential adopters. These issues have begun to emerge as important priorities in some areas of mental health intervention research, but in only a few instances to now have these concerns led to new strategies for designing and implementing initiatives (e.g., Drake et al. 2001).

A number of our studies have incorporated strategies within specific intervention designs to increase sustainability, such as insisting on the use of local community providers, rather than academic investigators, to deliver the cognitive behavioral therapy in the CBITS study (Kataoka et al. 2006). More generally, as previously indicated, one of the main purposes of engaging stakeholders through a participatory approach is to increase the relevance and sustainability of community health interventions.

An engagement process can build trust, ownership, and therefore commitment to research-based system change and improvement by shifting authority of action to consumers, community members, and community-based agencies most affected by programs (Minkler and Wallerstein 2004). At the same time, it can help sustain the level of communication and resource exchange often required in adapting and implementing the complex, multi-faceted interventions involving diverse stakeholders characteristic of many QI initiatives for mental health, as we have found in the Witness for Wellness and other community-partnered studies (Bluthenthal et la. 2006; Jones and Wells 2007).

Our experiences across a variety of interventions for mental health care also have frequently illustrated how implementation goals—which may vary across different contexts and stakeholders over time—can alter intervention and dissemination strategies. For example, in our Partners in Care study of QI for depression, differences in turnover and the personalities and skills of key personnel across the 46 participating primary care sites were considered likely factors affecting the enthusiasm for the study and behavior of intervention providers, such as the persistence and creativity displayed by nurse case managers in following up with elusive patients (Rubenstein et al. 1999). In the Witness for Wellness initiative, the goals of both academic and community partners have shifted—the former evolving from disseminating the specific Partners in Care findings to an emphasis on enabling community-derived strategies to improve depression care, and the latter focusing on methods more consistent with evaluation and partnership strategies more explicitly documented (Bluthenthal et al. 2006).

4.1.3. Intervention Outcomes

Each of the stages of diffusion can significantly affect outcomes for individuals in the community as well as for local organizations and systems of care. Individual-level outcomes include both care process (i.e., to what degree were evidence-based treatment and services received by individuals in need or at risk) and health status (i.e., whether individuals experienced any improvement in their health and functioning). Organization and system-level outcomes may include changes along various structural features of communities, such as service priorities for treating certain diseases, reorganization of health programs and resources, and new policies or collaborative arrangements. Both types of outcomes may result in changes to contextual factors at different levels of community and healthcare systems, as illustrated in the reverse arrow across the top of Figure 2.

These changes in contextual factors affect the capacity of community systems and stakeholders. Building local capacity, as described previously, is another main purpose of our community-partnered approach, whether in the form of mobilizing a community to address depression care and support wellness (Witness for Wellness), enhancing the ability to sustain and spread a specific health intervention for trauma (CBITS), or increasing collective knowledge of community assets and collaborative interchange around mental health and substance abuse needs (the Partnership Initiative).

4.2. Evaluation Process

The bottom portion of Figure 2 distinguishes three types of evaluation applicable to the components of the diffusion process described above and the research questions they pose: (1) capacity and needs assessment of contextual factors, (2) implementation and process evaluation of stages of diffusion, and (3) outcome and impact evaluation of patient and system outcomes. Each mode of evaluation provides important data for building an evidence base on successful dissemination and implementation strategies, as well as for guiding interventions as they are disseminated and implemented.

4.2.1. Capacity and Needs Assessment

As noted earlier, to understand the diffusion of an intervention—why it was or was not adopted, implemented as intended, or sustained over time—and to generalize the feasibility of dissemination and implementation strategies across healthcare and community settings, requires examining the context into which the intervention is introduced. Capacity assessments address the questions, in some form or another, of the types and strength of contextual factors described above that are present among stakeholders in healthcare or community settings. Needs assessments address a similar set of questions, but focus on what issues are most pressing and what gaps exist in various contextual factors (e.g., interest, resources, information, linkages, etc.) from the perspectives of different stakeholders of their needs or of the system as a whole.

Although studies of diffusion commonly measure contextual factors post-hoc, it is necessary to conduct prospective “baseline” assessments of context for initiatives that intend to produce change in the underlying contexts and stakeholder capacities sustaining interventions. For example, an explicit objective of the Partnership Initiative has been to assess perceived community health needs, priorities, and current (and desired) partnerships of community-based agencies in order track these dimensions of community-level systems of care over time (Stockdale, Mendel et al. 2006).

Examining contextual factors prospectively also affords essential levers for answering questions of how to identify appropriate interventions as well as gauge their “political opportunity” or feasibility (Kurzman 1998), i.e., the balance of support or opposition for their introduction within a given setting (Greenhalgh et al. 2004). The CBITS study was preceded by a needs assessment among community clergy leaders in which more than three-fourths felt that mental health services were an appropriate and needed ministry of their churches, yet only two percent were formally involved in such services with specialty mental health providers (Dossett et al. 2005). These findings prompted a local faith-based health partnership to explore more formal methods of providing mental health care, which eventually led to the implementation of the CBITS program in the school of one of their partner churches (Kataoka et al. 2006).

These assessments similarly provide data for answering questions of how to tailor or adapt interventions and dissemination strategies to particular settings—a critical step in the transportability of interventions (Schoenwald and Hoagwood 2001). For instance, Rogers (2003) delineates a number of attributes of innovations associated with successful diffusion, such as “relative advantage” (the extent to which an innovation is believed to be better than the current model of care) and “compatibility” (the degree to which an innovation is perceived to be consistent with existing values, resources, and needs of potential adopters). As the definitions of these attributes suggest, assessing potential intervention designs on these criteria depends to a large extent on knowledge of stakeholders and their particular contexts.

In the Witness for Wellness initiative, the initial kick-off community conference was designed to yield a rich source of data on the acceptability and appropriate tailoring of interventions (Bluthenthal et al. 2006). This type of information has continued to be generated through the project’s various workgroups and periodic follow-up community meetings (Chung et al. 2006; Stockdale, Patel, et al. 2006; Jones et al. 2006), utilizing innovative methods, such as audience response systems, to facilitate discussion and document information (Patel et al. 2006). Likewise, the CBITS project conducted initial focus groups with school parents, which began the a process of feedback on tailoring both the implementation and clinical intervention (most notably in sensitizing clinicians to the spiritual lives of students and incorporating their religious coping strategies into the therapeutic techniques). This early input and influence in the intervention’s design later proved a significant factor in the level of “buy-in” achieved among parents and other stakeholders (Kataoka et al. 2006).

From a community-participatory perspective, engaging community members even more fully as partners in all phases of the research process can represent a valuable strength-building mechanism to enhance the ability of stakeholders to understand and apply research results, conduct evaluations, and analyze their own needs and capacities (Minkler and Wallerstein 2004; Israel et al. 2005). The Talking Wellness workgroup in particular has demonstrated that such engagement is feasible even with so-called “grassroots” members of communities who have little or no familiarity with scientific evaluation, and can be especially valuable in developing community-appropriate instruments and building appreciation of research goals and methods among community stakeholders (Chung et al. 2006).

4.2.2. Implementation and Process Evaluation

Implementation and process evaluations answer the questions of the process by which intervention and dissemination strategies have been developed and how the implementation and other stages of diffusion have unfolded in practice. Opening what is, for most current health intervention studies, a “black box” is crucial to accumulating evidence on effective methods for tailoring intervention design and dissemination to community settings. Without such implementation and process evaluations (Rossi, Freeman, and Lipsey 1999; Steckler and Linnan 2002), it is difficult to confidently ascertain why certain outcomes were obtained or to explain variation in outcomes in a manner that can be used to improve future intervention design and dissemination strategies (Hohmann and Shear 2002).

For studies that expect strict fidelity to the implementation of an intervention as initially designed, it is important to confirm adherence in order to differentiate whether negative or non-results can be attributed to the intervention itself or to poor implementation (Fixsen et al 2005), such as incomplete adherence to distinct program components (Wells et al. 2000; Rubenstein et al. 1999). But natural adaptations during the course of implementation may also provide useful information—such as barriers and challenges to application of the intervention, or useful improvements—rather than simply random “noise” or variation (Orwin 2000).

Depending on the objectives of a study, it is possible to feed back observations of intervention fidelity, adaptation, and other results of process evaluations to stakeholders during implementation through formative evaluation mechanisms (Fitzpatrick, Sanders, and Worthen 2004; Patton 2001). In community participatory research, it may be imprudent, if not unethical, to withhold such formative data from community stakeholders, especially when they are involved as research partners (Israel et al. 2002). Almost all of our community-partnered projects incorporate feedback and iterative discussion of formative results among community and academic partners (Jones and Wells 2007). However, as noted in the preliminary evaluation of Witness for Wellness, evaluators must acknowledge the lack of objectivity inherent in such an approach, even when following rigorous research designs (Bluthenthal et al. 2006), and the timing and effects of such formative feedback must be documented and accounted for as part of the implementation and process evaluation itself.

In addition to providing “hard” statistical data on levels of implementation, we have also found process evaluations useful in providing “stories” that illustrate dissemination and implementation processes in ways that are compelling to health service researchers, practitioners, and community members alike. Such stories, or instructive narratives, serve not only to highlight awareness of implementation issues and their nuances, but also as a means for examining complex processes and relating how analytic factors interact and play out over time (Bate 2004). For example, personal narratives (written, video, and audio) of participation in the Witness for Wellness kick-off conference and other activities convey the impact and methods of community engagement in ways not possible through the questionnaire surveys of participants alone (Bluthenthal et al. 2006; Chung et al. 2006).

4.2.3. Outcome and Impact Evaluation

The ultimate research questions of the evaluations proposed in this framework, and in most health intervention studies, are whether and how an intervention introduced has produced changes in outcomes for individuals in need of services or at risk for particular health conditions. Outcome evaluation focuses on the degree to which individuals received evidence-based treatments or services and whether individuals experienced any improvement in health, functioning, or quality of life as a result. Impact evaluation considers the attributable effects of the intervention on wider policy concerns, such as the incidence, prevalence, and social and economic consequences of a particular disease or condition.

In terms of long-term progress in the health of communities, however, one of the most important impacts to assess is the effect of diffusion on organizational and system-level outcomes, i.e., on the context itself. Are the attitudes or priorities of stakeholder groups toward a disease or type of treatment different after the dissemination of an intervention? How have processes of care and organizational routines been altered? Have there been any shifts in the roles of providers or other stakeholders within the community? Such changes have implications for the capacity of stakeholders individually and collectively to sustain current activities and disseminate new interventions into the future. As discussed, building these capacities is a central goal—although certainly not the sole province—of a community-partnered research approach.

The results of outcome and impact are typically reported via some form of summative feedback at the end of a research study. Certain study designs may require all three points of feedback during the evaluation and diffusion processes (intervention development, formative, and summative), as in our community-based projects. However, even research that only reports findings after the end of the study should, if at all possible, include the results of all three types of evaluations in order to allow the pooling of findings on intervention, implementation, and dissemination strategies across studies. Unfortunately, as Shojania and Grimshaw (2005) observe, not reporting such information is currently the norm in the literature.

5. Study Design and Methodological Challenges

Although still in relatively early stages, our approach and framework presented here have highlighted key methodological challenges for designing and conducting implementation research in healthcare contexts and have generated a number of insights and directions for building evidence on effective dissemination and evaluation strategies.

5.1. Measurement and analysis

In our center’s attempt to assess dissemination context and process, we have tried to use validated constructs and measures whenever available, such as standard questionnaire items for organizational culture and climate (e.g., Scott et al. 2003; Glisson and Hemmelgarn 1998). However, in order to meaningfully capture and understand the dissemination process, constructs and measures must fit the population, disease condition, treatments, and service settings pertaining to specific interventions. For example, the collaboratively designed surveys of students in the CBITS study were comprehensive in including questions not only on trauma-related and other psychiatric symptoms, but also on school and social functioning and level of spirituality and religious support (Kataoka et al. 2006).

Similar measurement issues arise in examining the stages of diffusion, given the unique challenges of studying process over time among diverse sets of stakeholders in healthcare and community settings. As a result, a number of concepts and constructs remain untested, and many measures incorporated into our studies with regard to both contextual factors and dissemination and implementation processes are new, at least in application to health and mental health service interventions (e.g., network analytic indicators in the Partnership Initiative).

The broad classes of contextual factors and processes outlined in the framework are intended to permit customization of constructs and indicators while retaining generalizability across studies. But the problem of determining appropriate measures of contextual constructs in particular intervention settings remains a major challenge. This issue is exacerbated by the tendency of the academic literature to report a myriad of potential indicators—many substantively similar to one other—that have been shown to have a statistically significant influence on adoption or spread (Stockdale, Mendel et al. 2006). We have thus found it necessary to rely on exploratory methods (e.g., focus groups, planned community forums, and semi-structured interviews) to help identify relevant constructs and indicators for particular interventions and settings. We have also found the wealth of experiential knowledge of collaborative stakeholders to be an especially useful benefit of a participatory research approach in sorting, selecting, and developing appropriate measures (Chung et al. 2006). For example, the community collaborators in the Partnership Initiative were instrumental in helping identify relevant aspects of community capacity to assess (e.g., general interest and ability to partner) and how to best elicit this information from agencies addressing mental health and substance abuse needs (Stockdale, Mendel et al. 2006).

By proactively applying and testing such measures, we hope to accumulate sets of indicators that meaningfully assess similar contextual and implementation constructs across various settings and interventions. This type of measurement approach is intended to aid both the comparative analysis of intervention experiences and, as we discuss next, the systematic examination of the link between implementation and outcomes.

Outcome assessment at the provider and client level has been a strength of the center’s research to date, but as yet has not been systematically related to data gathered on organizational and community context and implementation process, nor integrated to a significant extent with the effects of engagement initiatives on organizational outcomes (Bluthenthal et al. 2006). As with the field in general, analyses linking implementation process and intervention outcomes have yet to be fully realized partly due to a number of inherent challenges of the design of community-based studies, including small samples of communities or intervention sites, which result in reduced statistical power, complexity in estimating sample size requirements, and challenges in obtaining comparable control or study groups (Koepsell et al. 1992).

Despite these difficulties, other research we have participated in has demonstrated that it is possible to reliably measure the intensity of implementation across a range of health conditions, including depression and other illnesses (Pearson et al. 2005), and to systematically relate these indicators to implementation effectiveness both descriptively (Meredith et al. 2006) and predictively (Shortell et al. 2004). We intend to extend such techniques to studies in the center based on more participatory-oriented research designs, and are particularly looking to this framework to assist in integrating these kinds of data and analysis.

5.2. Resources, participation, and power-sharing

Another key set of challenges, also recognized by others (Hohmann and Shear 2002; Schoenwald and Hoagwood 2001), are the additional research funding and resources required to conduct implementation and process evaluations in particular (and to some extent, capacity and needs assessments) not included in conventional health intervention research, at least not to the degree necessary to advance evidence on dissemination and implementation issues. These additional resources can be substantial, including support for time-intensive data collection and analysis, investigators with organizational and mixed methods expertise, and partner participation in studies utilizing collaborative stakeholder designs. A project of the scope of Witness for Wellness required over $250,000 in development funds in the first year alone, a figure that could not fully be anticipated at the outset given the character of the initiative as an action research project with evolving goals, processes, and participants (Bluthenthal et al. 2006).

Our experiences with studies such as these have demonstrated that extensive research partnership is feasible with diverse community stakeholders, but that each stakeholder brings unique sets of interests and capacities. As a consequence, the time and effort required to build, negotiate, and manage relationships (which can be nontrivial in the least participatory of service intervention studies) can become increasingly substantial as the level of collaboration with stakeholders in the dissemination and evaluation process increases, leaving participants both “enriched and overwhelmed” (Bluthenthal et al. 2006).

Many community members, particularly at the grass-roots level, have access to more modest administrative infrastructure and are much more constrained in their time, compared to academic partners whose regular work more fully compensates them and accommodates community research projects. These disparities exacerbate perceived imbalances in participation, status, and control among participants (Stockdale, Patel, et al. 2006). Thus, we have worked hard in our community-partnered initiatives to lessen these inequities (e.g., over half the first-year funds cited above went to community agencies and individuals to support their participation) and ensure appreciation for different interests, authentic shared decision-making, and mutual “win-win” for all parties (Jones and Wells 2007; Wells et al. 2004).

To address these challenges, our center’s approach, as touched on throughout this paper, has expanded over time to incorporate a range of interrelated dissemination and implementation research strategies. Most notably, these have included tailoring intervention delivery to the characteristics of specific stakeholder networks and communities (Kataoka et al. 2006; Punzalan et al. 2006; Chung et al. 2006), gaining experience with community engagement and coalition development strategies (Wells et al. 2006; Bluthenthal et al. 2006; Kataoka et al. 2006), and merging a participatory research process with more conventional assessments of organizational and partnership capacities (Stockdale, Mendel et al. 2006).

In future work, such as our recently funded Community Partners in Care study, we plan to integrate the lessons and experiences accumulated so far into comprehensive demonstrations of community engagement and partnership strategies and their progressive impact over time from proximate outcomes on the stakeholders participating in the interventions to longer-term changes in the health of individuals and capacity of communities. The framework presented here is expected to help guide, as well as evolve with, these efforts.

6. Conclusion

This framework, born out of our intervention research on the quality of mental health and related care, attempts to bridge the research-to-practice gap by providing a theoretically-grounded understanding of the multi-layered nature of community and healthcare contexts and the mechanisms by which new practices and programs diffuse within these settings. It also distinguishes among key aspects of the diffusion process, including contextual factors, adoption, implementation, and sustainment of interventions, showing how evaluation of each component is necessary to explain the course of dissemination and eventual outcomes for individual and organizational stakeholders.

Just as disseminating health interventions within complex and varied community contexts is no easy task, fully applying such a comprehensive framework for conducting and assessing community dissemination may appear a daunting challenge. First, to adequately study the transportability of health interventions in “real world” community settings requires a set of research skills to which many investigators in health services research may not currently be accustomed. This conclusion holds whether or not investigators employ the kinds of community-partnered and participatory approaches we have pursued. Consequently, health services research as a field needs to utilize conceptual insights and research methods from social science disciplines that are particularly suited to studying multiple levels and processes of change within social systems. These include case study designs and techniques for triangulating qualitative and quantitative data (Goodman et al. 1999, 2000). A mixed qualitative and quantitative approach may be usefully applied within each of the three areas of evaluation described in the framework (context, implementation, outcomes), as well as especially valuable in linking across these types of assessments.

Second, it would be impossible and highly unrealistic for any single study to incorporate all contextual variables, stakeholders and levels within a given community, even for the most ambitious project. Rather, the framework seeks to encourage studies to take into account key dimensions of local settings and drivers of diffusion, as well as to expand the conventional scope of evaluation to include the “black boxes” of intervention development and stages of diffusion. Most importantly, the framework is intended to provide a conceptual basis for organizing research and results across studies addressing different aspects of local contexts and pieces of the dissemination process (Grimshaw et al. 2004; Shojania and Grimshaw 2005; ICEBeRG 2006).

We have partially illustrated this function with the three main examples used throughout this paper, which ranged from the adaptation and implementation of a specific mental health intervention in an individual school-site (CBITS), to assessments of partnership capacities and priorities in two communities meant to stimulate collective dialogue and “pre-adoption” activities (the Partnership Initiative), and a more grass-roots, multi-pronged collaboration in one community to combat depression, involving a variety of needs assessments, evaluations of different intervention development and capacity-building activities, and eventually community impact studies as the initiative progresses (Witness for Wellness).

Through the proposed framework, we seek to advance theory and application related to critical issues of dissemination and implementation within health services research. Moreover, our approach advocates moving beyond studying context and implementation merely as a way of explaining the quality gap, to utilizing this information to develop, test, and accrue knowledge on novel strategies for mobilizing healthcare and community systems to adopt and sustain evidence-based interventions that—despite their complexity, challenges, and imperfections—offer proven and tangible benefits to individuals and the communities in which they live.

Acknowledgments

This article was prepared under the auspices of the UCLA/RAND NIMH Center for Research on Quality in Managed Care and supported by funding from the National Institute of Mental Health, Grants# P30 MH068639 and P50 MH054623 (Wells, PI), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation #038273 (Wells, PI), and the NIH National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities #1P20MD00182-01 (Norris, PI). The authors would like to thank the participants of the NIMH Conference on Advancing the Science of Implementation, David Chambers of NIMH, and the anonymous reviewers for their insights and comments on earlier versions of this paper.

References

- Abrahamson E, Fairchild G. Management fashions: Lifecycles, triggers, and collective learning processes. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1999;44(4):708–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Jaycox LH, Duan N, LaBorde AP, Rea MM, Murray P, Anderson M, Landon C, Tang L, Wells KB. Effectiveness of a quality improvement intervention for adolescent depression in primary care clinics: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:311–319. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social Learning Theory. Prentice-Hall International; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media Psychology. 2001;3:265–299. [Google Scholar]

- Bate SP. The role of stories and storytelling in organizational change efforts: The anthropology of an intervention within a hospital. Intervention. Journal of Culture, Organization and Management. 2004;1(1):27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bate SP, Robert G. Knowledge management and communities of practice in the private sector: Lessons for modernizing the National Health Service in England and Wales. Public Administration. 2002;80(4):643–663. [Google Scholar]

- Bate SP, Robert G, Bevan H. The next phase of health care improvement: What can we learn from social movements? Quality & Safety in Health Care. 2004;13(1):62–66. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2003.006965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benford RB, Snow DA. Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology. 2000;26:611–639. [Google Scholar]

- Bluthenthal RN, Jones L, Fackler-Lowrie N, Ellison M, Booker T, Jones F, McDaniel S, Noini M, Williams KR, Klap R, Koegel P, Wells KB. Witness for Wellness: Preliminary findings from a community-academic participatory research mental health initiative. Ethnicity and Disease. 2006;16(S1):18–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JS, Duguid P. Organizational learning and communities of practice. Organization Science. 1991;2(1):40–57. [Google Scholar]

- Burns LR, Wholey DR. Adoption and abandonment of matrix management programs: Effects of organizational characteristics and interorganizational networks. Academy of Management Journal. 1993;36:106–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain M, Mittman R. I-Health Report Series. California Health Care Foundation; Oakland, CA: 2002. Diffusion of innovation in healthcare. [Google Scholar]

- Chung B, Corbett CE, Boulet B, Cummings JR, Paxton K, McDaniel S, Mercier SO, Franklin C, Mercier E, Jones L, Collins BE, Koegel P, Duan N, Wells KB, Glik D. Talking Wellness: A description of a community-academic partnered project to engage an African-American community around depression through use of poetry, film, and photography. Ethnicity and Disease. 2006;16(S1):67–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Syme SL. Social Support and Health. Academic Press; Orlando, FL: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JS, Katz E, Menzel H. Medical Innovation. Bobbs-Merrill; New York: 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Davis GF, McAdam D, Scott WR, Zald MN. Social Movements and Organization Theory. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio PJ, Powell WW. The Iron Cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review. 1983;48:147–60. [Google Scholar]

- Dossett E, Fuentes S, Klap R, Wells K. Brief reports: Obstacles and opportunities in providing mental health services through a faith-based network in Los Angeles. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56(2):206–208. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Essock SM, Shaner A, Carey KB, Minkoff K, Kola L, Lynde D, Osher FC, Clark RE, Rickards L. Implementing dual diagnosis services for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:469–1597. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.4.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng E, Briscoe J, Cunningham A. The effect of participation in state projects on immunization. Social Science and Medicine. 1990;30(12):1349–1358. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90315-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellin P. Understanding American communities. In: Rothamn J, Erlich JL, Tropman JE, editors. Strategies of Community Organization. 5th edition Peacock; Itasca, Ill: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ferlie EB, Shortell SM. Improving the quality of health care in the United Kingdom and the United States: A framework for change. Milbank Quarterly. 2001;79(2):281–315. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick JL, Sanders JR, Worthen BR. Program Evaluation: Alternative Approaches and Practical Guidelines. 3rd edition Allyn & Bacon; Boston: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fixen DL, Naoom SF, Blasé KA, Friedman RM, Wallace F. Implementation Research: A Synthesis of the Literature. Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, University of South Florida; Tampa, Florida: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Galaskiewicz J. Interorganizational relations. Annual Review of Sociology. 1985;11:281–304. [Google Scholar]

- Ganz M. Resources and resourcefulness: Strategic capacity in the unionization of California agriculture, 1959-1966. American Journal of Sociology. 2000;105:1003–1062. [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Lichtenstein E, Marcus AC. Why don’t we see more translation of health promotion research to practice? Rethinking the efficacy-to-effectiveness transition. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(8):1261–1267. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Hemmelgarn AL. The effects of organizational climate and interorganizational coordination on the quality and outcomes of children’s service systems. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1998;22:401–421. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(98)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, James LR. The cross-level effects of culture and climate in human service teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2002;23:767–794. [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Schoenwald SK. The ARC organizational and community intervention strategy for implementing evidence-based children’s mental health treatments. Mental Health Services Research. 2005;7(4):243–259. doi: 10.1007/s11020-005-7456-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. Principles and tools for evaluating community-based prevention and health promotion programs. In: Brownson RC, Baker EA, Novick LF, editors. Community-Based Prevention. Aspen Publishing; Maryland: 1999. pp. 211–227. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. Evaluation of community-based health programs: An alternate perspective. In: Schneiderman, Tomes, Gentry, Silva, editors. Integrating Behavioral and Social Sciences with Public Health. American Psychological Association Press; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: Systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Quarterly. 2004;82(4):581–629. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannan MT, Freeman J. Structural inertia and organizational change. American Sociological Review. 1984;49:149–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hannan MT, Freeman J. Organizational Ecology. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Haveman HA. Follow the leader: Mimetic isomorphism and entry into new markets. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1993;38:593–627. [Google Scholar]

- HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services) Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health; Rockville, MD: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann AA, Shear KM. Community-based intervention research: Coping with the “noise” of real life in study design. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:201–207. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IOM (Institute of Medicine) Bridging the Gap Between Practice and Research: Forging Partnerships with Community-Based Drug and Alcohol Treatment. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IOM (Institute of Medicine) Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies From Social and Behavioral Research. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Implementation Science About Implementation Science. 2006 Retrieved October 25, 2006 from http://www.implementationscience.com/info/about/

- Israel B, Eng E, Schulz A, Parker E, editors. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Israel B, Schulz A, Parker E, Becker, Allen A, Guzman R. Critical issues in developing and following community based participatory research principles. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. Jossey-Bass Publishers; San Francisco: 2002. pp. 53–75. [Google Scholar]

- Jones D, Franklin C, Butler BT, Williams P, Wells KB, Rodriquez MA. The Building Wellness project: A case history of partnership, power sharing, and compromise. Ethnicity and Disease. 2006;16(S1):18–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007;297(4):407–410. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka S, Fuentes S, O’Donoghue VP, Castillo-Campos P, Bonilla A, Halsey K, Avila JL, Wells KB. A community participatory research partnership: The development of a faith-based intervention for children exposed to violence. Ethnicity and Disease. 2006;16(S1):89–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Unützer J, Fan MY, Williams JW, Schoenbaum M, Lin EH, Hunkeler EM. Cost-effectiveness and net benefit of enhanced treatment of depression for older adults with diabetes and depression. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(2):265–270. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.02.06.dc05-1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimberly JR. Managerial innovation. In: Nystrom P, Starbuck W, editors. Handbook of Organizational Design. Oxford University Press; New York: 1984. pp. 84–104. [Google Scholar]

- Koepsell TD, Wagner EH, Cheadle AC, Patrick DL, Martin DC, Diehr PH, Perrin EB. Selected methodological issues in evaluating community-based health promotion and disease programs. Annual Review of Public Health. 1992;13:31–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.13.050192.000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurzman C. Organizational opportunity and social movement mobilization: A comparative analysis of four religious movements. Mobilization. 1998;3:23–49. [Google Scholar]

- Laffont J, Martimort D. The Theory of Incentives: The Principal-Agent Model. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Leatherman S, Berwick D, Iles D, Lewin LS, Davidoff F, Nolan T, Bisognano M. The business case for quality: Case studies and an analysis. Health Affairs. 2003;22(2):17–30. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.2.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenfant C. Clinical research to clinical practice—Lost in translation? New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349:868–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa035507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M, Marsteller J, Shortell SM, Mendel P, Pearson ML, Wu SY. Motivating change to improve quality of care: Results from a national evaluation of quality improvement collaboratives. Health Care Management Review. 2005;30(2):139–56. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200504000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomas J. Diffusion, dissemination, and implementation: Who should do what? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;703:226–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb26351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomas J, Enkin M, Anderson GM, Hannah WJ, Vayda E, Singer J. Opinion leaders vs. audit and feedback to implement practice guidelines: Delivery after previous cesarean section. JAMA. 1991;265(17):2202–2207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke DA, Harris JK. Network analysis in public health: History, methods, and applications. Annual Review of Public Health. 2007;28:16.1–16.25. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiman LA, Becker MH. The health belief model: Origins and correlates in psychological theory. Health Education Monographs. 1974;2:336–353. [Google Scholar]

- McAdam D, McCarthy JD, Zald MN. Introduction: Opportunities, mobilizing structures, and framing processes—toward a synthetic, comparative perspective on social movements. In: McAdam D, McCarthy JD, Zald MN, editors. Comparative Perspectives on Social Movements: Political Opportunities, Mobilizing Structures, and Cultural Framings. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1996. pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy JD, Zald MN. Resource mobilization and social movements: A partial theory. American Journal of Sociology. 1977;82:1212–1241. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Cook JM. Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:415–444. [Google Scholar]

- Mendel P. Chartbook of Preliminary Study Findings. Health Care for Communities (HCC) Partnership Initiative. UCLA/RAND NIMH Center for Research on Quality in Managed Care; Los Angeles: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mendel P, Fuentes S. Partnering for Mental Health and Substance Abuse Needs in Los Angeles: A Community Feedback Report from the Health Care for Communities (HCC) Partnership Initiative Community Conference held July 7th, 2006. UCLA/RAND NIMH Center for Research on Quality in Managed Care; Los Angeles: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith LS, Mendel P, Pearson M, Wu SY, Joyce G, Straus JB, Ryan G, Keeler E, Unützer J. Implementation and maintenance of quality improvement for treating depression in primary care. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57:48–55. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith LS, Rubenstein LV, Rost K, Ford DE, Gordon N, Nutting P, Camp P, Wells KB. Treating depression in staff-model versus network-model managed care organizations. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1999;14(1):39–48. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00279.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith LS, Sturm R, Camp P, Wells KB. Effects of cost-containment strategies within managed care on continuity of the relationship between patients with depression and their primary care providers. Medical Care. 2001;39(10):1075–1085. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200110000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. Jossey-Bass Publishers; San Francisco: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Torrey WC, Lynde D, Singer P, Drake RE. Implementing evidence-based practices for people with severe mental illness. Behavior Modification. 2003;27:387–411. doi: 10.1177/0145445503027003007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIH (National Institutes of Health) Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health (R01 Program Announcement) 2006a Retrieved on October 25, 2006, from http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR-06-039.html.

- NIH (National Institutes of Health) NIH Roadmap Request for Information (RFI); Translation; The Science of Knowledge Dissemination, implementation and integration. 2006b Retrieved from http://www.reffectcomments.org/Roadmap/PR.aspx.

- NHCPI (National Health Care Purchasing Institute) Provider Incentive Models for Improving Quality of Care. Bailit Health Purchasing, LLC; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- NIMH (National Institute of Mental Health) Translating Behavioral Science into Action. A Report of the National Advisory Mental Health Council Behavioral Science Workgroup. Bethesda, MD: 2000. NIMH Publication No.11-4699. [Google Scholar]

- Orwin RG. Assessing program fidelity in substance abuse health services research. Addiction. 2000;95(Supplement 3):S309–27. doi: 10.1080/09652140020004250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor JC, Meindl J, Hunt R. The quality virus: Interorganizational contagion in the adoption of Total Quality Management. In: Alvarez JL, editor. Diffusion and Consumption of Business Knowledge. St. Martin’s Press; New York: 1998. pp. 201–18. [Google Scholar]