Abstract

Objective

The Keep It Off trial evaluated the efficacy of a phone-based weight loss maintenance intervention among adults who had recently lost weight in Minnesota (2007–2010).

Methods

419 adults who had recently lost ≥ 10% of their body weight were randomized to the “Guided” or “Self-Directed” intervention. Guided participants received a 10 session workbook, 10 biweekly, eight monthly and six bimonthly phone coaching calls, bimonthly weight graphs and tailored letters based on self-reported weights. Self-Directed participants received the workbook and two calls. Primary outcomes are weight change and maintenance (regain of < 2.5% of baseline body weight).

Results

Mixed model repeated-measures analysis examining weight change revealed a significant time by treatment group interaction (p < 0.0085). Guided participants regained significantly less weight than Self-Directed participants at 12 and 24 months. The odds of 24 month maintenance were 1.37 (95% CI: 0.97–2.03) times greater in the Guided than in the Self-Directed group. When maintenance rates were compared across all follow-ups, there was a consistently higher maintenance rate for Guided participants (HR 1.31, 95% CI: 1.12 – 1.54).

Conclusions

A sustained, supportive phone- and mail-based intervention promotes weight loss maintenance relative to a brief intervention for participants who have recently lost weight.

Keywords: weight loss, maintenance, obesity, behavioral intervention

Introduction

Long-term weight loss maintenance remains a challenge for obesity treatment.(Jeffery et al., 2000; Sarwer et al., 2009) Strategies to improve outcomes have included increasing treatment duration(Levy et al., 2010; Perri et al., 2001; Perri et al., 1989) and incorporating lessons learned (e.g., high physical activity levels) from the National Weight Control Registry (NWCR).(Jeffery et al., 2000) (Jeffery et al., 2003; Tate DF, 2007) Virtually all past intervention studies have started by inducing weight loss among overweight or obese individuals, with the initial weight loss period typically the most intensive treatment phase. The maintenance phase occurs later when participants often attend treatment sessions less frequently, and plausibly after the novelty of treatment may have faded.(Jeffery et al., 2003) (Jeffery et al., 2004; Jeffery et al., 1993)

A novel alternative to starting maintenance treatment when people are at a low motivational ebb may be to develop exclusively maintenance-focused programs, without regard to initial weight-loss methods. Intervention content for such a program would be tailored specifically for maintenance and provide therapeutic contact when people are at highest risk for weight regain. We are aware of only one other published study, the Study to Prevent Regain (STOP Regain) that used a similar approach to recruitment.(Wing et al., 2006) STOP Regain tested the efficacy of a face-to-face program and an Internet-based program, compared with a newsletter control group, in preventing 18 month weight regain among participants who had lost a minimum of 10% of their body weight. Results at the end of 18 month follow up indicated that the face-to-face group was most promising. Participants in the face-to-face group gained 2.5 kg (sd=6.7) on average compared to 4.7 kg (sd=8.6) and 4.9 kg (sd=6.5) in the Internet and control groups, respectively. Examination of weight loss maintenance as a dichotomous outcome (weight regain ≤ 2.5 kg) showed that both the face-to-face and Internet groups had higher rates of weight loss maintenance relative to control group participants. Among face-to-face participants, 54% were considered weight loss maintainers compared to 45% of Internet participants and 28% of control group participants.

Treatment delivery modality is an important consideration. Although the face-to-face intervention in the Wing et al(Wing et al., 2006) study was most effective, attendance at in-person sessions can be a barrier to participation. Phone-based counseling has been found to be a convenient and viable alternative to more intensive therapies for affecting a variety of health behaviors,(Curry et al., 1995; Eakin et al., 2009; Sherwood et al., 2006; Sherwood et al., 2010; The Writing Group for the Activity Counseling Trial Research Group, 2001) including weight-loss maintenance.(Perri et al., 1984b; Wing et al., 1996) To date, phone counseling has been evaluated only as a component of a program that started with weight-loss initiation.(Perri et al., 1984a; Wing et al., 1996)

New methods are needed for maintaining long-term weight loss to address the practical challenges identified in previous research and build on the current theoretical understanding of the processes associated with successful weight loss maintenance.(Rothman, 2000) Rothman argues that behavioral initiation and behavioral maintenance processes are driven by different decision criteria. Decisions regarding initiation focus on the favorability of future outcomes that will result from behavior change, an “approach-based” perspective. Alternatively, a decision to maintain a pattern of behavior is thought to be based on a person’s satisfaction with the outcomes produced by their current behavior, and not wanting to lose that satisfaction, an “avoidance-based” perspective. During weight loss initiation, individuals may be more focused on anticipated gains in valued outcomes, while in the maintenance phase, the focus may be more on avoiding anticipated losses in valued outcomes that would be associated with regaining weight. This model suggests that a key element of weight maintenance programs may be enhancing satisfaction with perceived benefits of having lost weigh. We reasoned that recruiting individuals who have recently intentionally lost weight may be an effective starting point and designed a maintenance-focused intervention to provide personalized support for individuals during a period when they are at high risk for weight regain, including helping them, appreciate the benefits of their weight losses despite the fact that they fallen short of their “dream weight.”

The Keep It Off study is a randomized clinical trial evaluating a 2 year phone and mail-based intervention for long-term weight-loss maintenance (“Guided”) in comparison to a brief phone-based intervention (“Self-Directed”). The Guided intervention integrates a core set of phone sessions focusing on key weight-loss maintenance behaviors and skills followed by continued self-monitoring and reporting of weight, bimonthly tailored feedback, monthly and bimonthly check-in calls and, for those who experience a small weight regain, additional outreach calls to problem-solve regarding weight-gain reversal strategies. Our primary goal was to assess the extent to which the Guided intervention helps participants maintain their weight loss over a two year period, relative to the Self-Directed Intervention. We present here the primary weight and weight loss maintenance outcome analyses and secondary analyses examining changes in dietary intake, physical activity, and self-weighing over time.

Methods

We have described recruitment and enrollment (May 2007 – September 2008) in greater detail elsewhere.(Sherwood et al., 2011) Briefly, we used multiple recruitment strategies (e.g., online and print newsletters through worksites with employees with HealthPartners (HP) insurance, HP website advertisements) to identify eligible participants, those who had intentionally lost at least 10% of their body weight during the past year. Adopting NWCR(Klem et al., 1997) procedures, participants were asked to provide documentation to ensure the veracity of their self-reported weight loss. Additional eligibility criteria were: 19 to 70 years old, previous year enrollment in the HP health plan, and BMI ≥ 20.5 kg/m2. Exclusion criteria included: anorexia nervosa history, bariatric surgery, modified Charlson (Charlson et al., 2008) score ≥ 3, a standard index of comorbidity calculated using prior year diagnoses of a broad range of serious medical conditions, non-skin cancer, congestive heart failure, use of a phone-based weight-loss program to achieve their recent weight loss, or current participation in another weight-management study. During screening calls, Keep It Off staff described the study and asked questions to assess study eligibility and interest. If interested and eligible, an in-person baseline visit was then scheduled during which the consent form was reviewed and signed, participants were weighed and measured, and completed baseline questionnaires. Figure 1 depicts a modified Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram describing study flow from recruitment through study completion.

Figure 1.

Modified CONSORT diagram for the Keep It Off trial

Study conducted in the Twin Cities Metropolitan Area, Minnesota, USA, 2007–2010.

Design

The study coordinator randomized 419 eligible participants in equal proportions to either the Keep It Off Guided or Self-Directed Intervention. Participants were allocated in blocks of 20 according to a study statistician-prepared schedule using a random numbers table and unobservable to the coordinator. Data collection points include baseline, six, 12, 18, and 24 month follow-up. The baseline, 12, and 24 month measurements were conducted in-person; six and 18 month measurements were conducted via telephone by evaluation staff blind to study condition.

Intervention

Self-Directed

The Self-Directed study arm included two phone coaching sessions scheduled two weeks apart. Self-Directed participants received a 10 chapter Keep It Off course book which topics such as key weight loss maintenance behaviors, weight loss history, physical activity, menu planning, stimulus control, problem solving, overcoming barriers to physical activity and healthy eating, relapse prevention, and body image and weight goals. Participants also received a one month Keep It Off logbook in which to record their eating, physical activity, and weight. During the two calls, participants reviewed the instructions for self-monitoring and the course book. Participants had no further contact with their phone coach.

Guided

The Guided study arm included 10 biweekly phone coaching sessions followed by eight monthly and six bimonthly calls, and bimonthly weight graphs and letters beginning at month eight. Guided participants received the Keep It Off course book described previously(Sherwood et al., 2011), but worked through it during 10 biweekly phone coaching calls and then transitioned to the monthly and bimonthly call phase. Guided participants received Keep It Off logbooks and reported their weight weekly for the study duration either during scheduled phone calls, by email, or on the study website. Participants were not given specific calorie and fat goals, but were encouraged to self-monitor dietary intake, calories, fat grams, and body weight in order to establish their optimal caloric range for weight maintenance. Participants were encouraged to work towards the goal of engaging in 60 to 90 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, most days a week. Participants also received bimonthly feedback weight graphs and reports based on their weight loss maintenance progress. Accompanying each mailing was a small incentive (e.g., Keep It Off pen, sticky notes, refrigerator magnet) for continuing participation. Finally, if participants showed a weight gain trend (i.e., 2 pounds or greater) and did not have a call scheduled in the next two weeks, phone coaches emailed or called them to provide extra support to help reverse the weight gain. Because we did not want to “flag” a weight gain that was likely to be temporary, we developed two algorithms that focused on weight across a 4 week period. The first call algorithm was used for people with valid data for 4 consecutive weeks of self-reported weights. Using all four of these values, participants were identified as needing a trigger call if a) the average of weights 3 and 4 was at least two pounds greater than the average of weights 1 and 2, or if b) weight 4 was at least two points greater than weight 1 and there was a steady increase from weight 1 to weight 4. The second call algorithm was used for people with at least one missing data value over 4 consecutive weeks of self-reported weights. Using available values, a participant would get identified as needing a Keep It Off phone coach to look at their data (and possibly recommend a trigger call) if the last observed value in the last 4 weeks was at least 2 pounds greater than the first observed value in the last 4 weeks. Before reaching out to a Guided participant for a “weight gain trigger” call, the data were reviewed by the intervention team. If there was an upcoming scheduled call with a participant, the Keep It Off phone coach would wait until that appointment to discuss the recent weight gain. The goal was to provide support when it might theoretically have been easier to reverse weight gain without responding to inconsequential weight gain. Participant reports of diet and activity were used to target which components of their weight-maintenance plan appeared to be contributing to weight gain. An action plan was developed, and follow-up phone calls were scheduled as needed to help the participant stabilize their weight.

Measures

Weight and height: At baseline, 12, and 24 month follow-up, weight and height were measured in person with participants in light clothing without shoes (Seca 770 Medical Scale; Seca 214 Portable Height Rod). At six and 18 months, weight was self-reported. Evaluation staff was blinded to study condition. Primary study outcomes were weight change, based on measured weights at baseline, 12, and 24 months, and weight maintenance, a dichotomous measure defined as a gain of <2.5% of baseline body weight. We created a second maintenance outcome variable to investigate the sensitivity of our findings to the definition of maintenance; this definition classified participants experiencing a regain of <25% of previously lost weight as maintainers. Secondary outcomes included self-reported calorie intake, self-reported physical activity, and self-weighing frequency. Calorie intake was assessed at baseline, 12 and 24 months with the Diet History Questionnaire (DHQ)(Subar et al., 2001; Thompson et al., 2002) instrument. Physical activity levels were estimated from responses to the Paffenbarger Physical Activity Questionnaire (PPAQ)(Harris et al., 1994; Paffenbarger et al., 1978), which was administered at baseline and each follow-up. Self-weighing frequency was obtained at baseline and each follow-up, by means of a survey item with seven possible frequencies, ranging from ‘never’ to ‘every day’; subjects’ self-weighing was categorized as occurring “at least once a day” or “less than once a day”.

Data Analysis

The first co-primary aim, to examine the outcome of weight change as a function of time and treatment group, was met through a linear mixed-effects regression. Our regression model featured weight change as a function of randomization group and time (12 and 24 month measures relative to Baseline), with a random intercept term for each subject. The second co-primary aim of the project, which was comparing probabilities of maintenance at 24 months between treatment groups, was addressed using logistic regression. The third major aim of the study was similar to the second, but instead of comparing only maintenance rates that were observed at 24 months, we wanted to compare maintenance rates in Guided and Self Directed participants at all four follow-up points. This comparison of maintenance across time was accomplished using the Andersen-Gill extension to Cox proportional hazards regression(Andersen and Gill, 1982), with a subject-level random effect, and employing exact conditional probabilities to handle tied failure times.

We used two protocols for data modification prior to our primary analysis. First, self-reported weights from midyear follow-ups were corrected for underreporting to the magnitudes observed by Spencer et al (2002)(Spencer et al., 2002), in subjects of matched weight and gender. Thereafter, the second data modification protocol was used to estimate weight values when data was missing: if an individual had complete data from staff-measured weights before and after the unobserved value, missing weight values were imputed by linear interpolation. If <2 staff-measured weights from before and after the missing data were available, we then attempted to interpolate individuals’ weights using the closest available self-reported weights from 6- and 18-month follow-ups. All missing weight values of patients for whom we did not measure again for the duration of the study (including all missing weights at 24 months), were imputed using the method of Wing et al.(Wing et al., 2006), i.e., assuming a 3.96 lb weight gain every six months since the last observation of that individual.

Our secondary aims were analysis of physical activity energy expenditure, total energy intake, and self-weighing frequency. The physical activity outcome variable was highly skewed, so we used a square root transformation of it, which was approximately normal in distribution, and better suited to the assumptions inherent in linear mixed-effects regression. As with our primary outcomes, we used logistic regression to compare binary dependent variables at study end, Cox regression to compare binary outcome rates across time, and linear mixed-effects regression models to compare continuous outcomes. When comparing continuous outcomes at a single point in time, these regression models reduced to two-sample t-tests.

A priori power analyses were carried out to determine the minimum detectable difference between groups in weight regain and weight-loss maintenance at 24 months at .90 power (α2 = .05) with a sample size of n=200 per group and 80% retention. The minimum detectable effects were estimated at .90 power to ensure joint significance of both outcome variables at power ≥.80. Statistics, tables and figures reflect the use of intention-to-treat protocol (that is, groups were analyzed by randomization rather than actual treatment received). All analyses were done in SAS v9.1 (Cary, NC).

Results

Sample Characteristics

We recruited and randomized 419 subjects. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the study participants. All measured characteristics of both groups were similar, including mean weight at baseline (Self-Directed: mean = 175.1 lbs, SD =36.3; Guided: mean = 176.7 lbs, SD = 34.7; p=0.648), amount of weight lost prior to study entry (Self-Directed: mean= 31.3 lbs, SD= 14.7; Guided: mean= 33.4 lbs, SD = 17.0), and percentage of weight lost prior to study entry (Self-Directed: mean= 15.7%, SD =5.0; Guided: mean =16.6%, SD=5.6). We obtained weight data from 84–93% of subjects at each follow-up (see figure 1), yielding a total of 727 staff-measured weight values from 12- and 24-month visits, and 762 weights that were self-reported at 6- and 18-month follow-ups, with the remaining187 missing weight values estimated through imputation and included in the primary outcome analyses.

Table 1.

Baseline descriptive characteristics of the Keep It Off study participants

| Self-directed (N=210) | Guided(N=209) | Overall (N=419) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) or % | Mean (SD) or % | Mean (SD) or % | |

| Baseline age (yrs) | 46.3 (10.6) | 46.6 (10.9) | 46.4 (10.7) |

| Baseline BMI (kg/m2) | 28.2 (5.6) | 28.6 (4.5) | 28.4 (5.0) |

| Baseline weight (lbs) | 175.1 (36.2) | 176.7 (34.7) | 175.9 (35.4) |

| % Weight loss prior to study entry | 15.7 (5.0) | 16.6 (5.6) | 16.2 (5.3) |

| Female | 82.4 | 80.9 | 81.6 |

| White | 90.0 | 92.4 | 91.2 |

| Black | 5.7 | 4.8 | 5.2 |

| Asian | 2.4 | 4.3 | 3.3 |

| Other race | 0.4 | 1.4 | 1.0 |

| Multiple races | 3.3 | 1.9 | 2.6 |

| Employed at least part-time | 87.6 | 86.6 | 87.1 |

| Had a college degree at baseline | 61.9 | 67.0 | 64.4 |

| Lost weight for health reasons | 79.0 | 75.5 | 77.2 |

| Lost weight for self-esteem | 22.9 | 27.4 | 25.2 |

| Diet as weight loss method | 41.6 | 45.7 | 43.7 |

| Program as weight loss method | 51.2 | 46.7 | 48.9 |

| Exercise as a weight loss method | 65.1 | 69.5 | 67.3 |

Study conducted in the Twin Cities Metropolitan Area, Minnesota, USA, 2007–2010.

Outcomes by treatment group

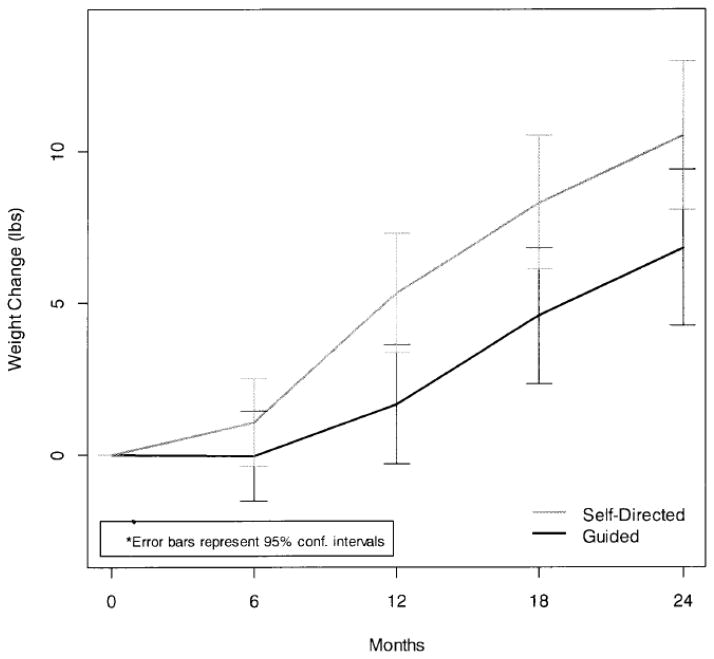

Table 2 shows mean weights and weight changes from baseline by treatment group, while figure 2 shows the average weight change trajectory by treatment group. Mixed model repeated-measures analysis of staff-measured weights revealed a significant time*treatment group interaction (p = 0.0085). Guided participants regained significantly less weight at 12, and 24 month follow-up relative to Self-Directed participants (p=0.005 and p=0.028, respectively).

Table 2.

Mean weight and weight change from baseline at 6, 12, 18, and 24 month follow-up by treatment group.

| Mean Weight (SD), lbs | Mean Weight Change (SD), lbs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Directed | Guided | Self-Directed | Guided | |

| 6 Months | 176.2 (37.2) | 176.7 (36.6) | 1.1 (10.2) | 0.0 (10.4) |

| 12 Months | 180.5 (39.4) | 178.4 (36.8) | 5.3 (13.6) | 1.7 (13.2) |

| 18 Months | 183.4 (39.9) | 181.3 (38.7) | 8.3 (15.6) | 4.6 (15.2) |

| 24 Months | 185.7 (40.7) | 183.6 (39.3) | 10.5 (16.8) | 6.8 (17.4) |

Study conducted in the Twin Cities Metropolitan Area, Minnesota, USA, 2007–2010.

Figure 2.

Net Weight Gain from Baseline by Time and Group.

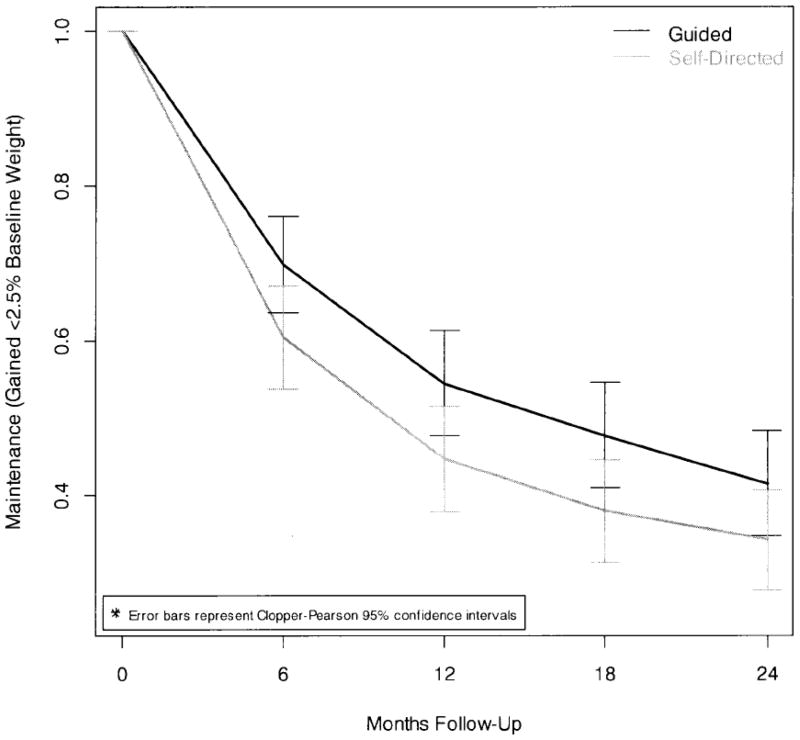

Figure 3 shows maintenance by treatment group at each follow-up. The odds of 24 month maintenance were 1.37 (95% CI: 0.92 – 2.03, p=0.122) times greater in the Guided than the Self-Directed group; this difference was not statistically significant. However, when rates of maintenance were compared across all follow-ups, we observed a consistently higher rate of maintenance in the Guided group (HR 1.31, 95% CI: 1.12 – 1.54, p =0.0002).

Figure 3.

Likelihood of Maintenance Loss by Time and Group.

Sensitivity to maintenance definition

We also investigated an alternative definition of weight maintenance, in which participants who had regained <25% of their previously lost weight would be considered ‘maintainers’. At 24-months, 189 (45.1%) of subjects were ‘non-maintainers’, while the other 230 participants (54.9%) experienced regain of <25% of their previously lost weight. This maintenance definition was somewhat less stringent: 7.2% (n=150) of all follow-up observations had gained at least 2.5% of body weight, but had not yet regained 25% or more of their previously lost weight. Meanwhile, at every observation in which an individual had regained 25% or more of their previously lost weight, the individual had also gained at least 2.5% of their baseline body weight. The intervention effect utilizing this more lenient definition was similar. The odds of achieving <25% regain at 24 months were 1.46 (95% CI: 0.99 – 2.14, p= 0.057) for Guided compared to Self-Directed participants. Similarly, in looking at maintenance across all follow-ups, the ratio of maintenance in the Guided group compared to the Self-Directed group was almost unchanged at 1.36 (95% CI: 1.18 – 1.57, p-value <0.0001).

Sensitivity to adjustment of self-reported weights

Weight values observed at 6- and 18-month follow-ups were self-reported. Unsurprisingly, all self-reported weights from 6 and 18 months were, on average, 4.8 pounds less than all staff-measured weights from baseline, 12 and 24 months (95% CI: −8.28 – −1.37, p= 0.0062), irrespective of time or treatment group. After applying weight- and gender-specific corrections to each weight value from 6- or 18-month follow-ups, we observed no difference between self-reported and staff-measured observations (mean difference: −0.57 lbs, 95% CI: −2.76 −3.91). Because our primary analyses of 12 and 24 month weight change from baseline and 24-month maintenance did not employ self-reported weight data, these corrections had no bearing upon either. Additionally, removing the self-reporting bias corrections appeared to have little effect on our analysis of maintenance at all follow-ups, with estimated maintenance using uncorrected weights being 1.33 (95% CI: 1.17 – 1.51) times greater in the Guided group.

Dietary Intake, Physical Activity and Self-Weighing

For Guided and Self-Directed participants, a decline in caloric consumption was observed at 12 months relative to baseline (p=0.011); however, this decrease in energy consumption was not sustained at 24 months. There was no group difference observed in caloric intake (kcal/day) at baseline (Self-Directed: mean= 1611, SD=641; Guided: mean= 1556, SD = 647) or 12 months (Self-Directed: mean =1505, SD = 608; Guided: mean =1466, SD =585). However, there was a statistically significant group difference in 24 month kcal/day consumption (Self-Directed: mean= 1587, SD = 633; Guided: mean= 1429, SD = 572; p=0.015). Average physical activity (√kcal/week) in both groups was significantly lower at later follow-ups (, p=0.01), but there was no statistical evidence of a treatment effect on physical activity at 24-months (Self-Directed: mean=1861, SD = 1659; Guided: mean=1759, SD = 1577).

Participants reported that they weighed themselves daily in 1029 of 1932 (53.8%) baseline or follow-up surveys. This included 191 participant responses in both treatment groups (51.6%) at 24-months. The odds of reporting daily weighing at 24 months were 1.97 (95% CI 1.31 – 2.99) times greater in the Guided, compared to the Self-Directed group, with about 60% of Guided participants reporting daily self-weighing compared to 43% of Self-Directed participants. Across all time points, the rate of maintaining daily self-weighing practices was 1.43 times higher in the Guided than the Self-Directed group (95% CI: 1.20 – 1.70, p <0.0001).

Discussion

The Keep It Off study is one of the first studies to examine the efficacy of a weight loss maintenance intervention among adults who have recently lost a clinically significant amount of weight prior to engagement in the research. Compared to participants who were randomized to a Self-Directed Intervention, Guided participants regained less weight over a two year follow-up period, with Guided participants on average gaining approximately four pounds less than Self-Directed participants. Guided participants were also somewhat more likely to be classified as weight loss maintainers over time. Although the likelihood of being considered a weight loss maintainer at 24 month follow-up was not statistically significant when maintenance was defined as regaining less than 2.5% of baseline body weight and only marginally significant when maintenance was defined as regaining < 25% of the weight lost prior to study entry, analyses examining rates of maintenance over time suggested that Guided participants had significantly higher rates of maintenance over time, using both maintenance definitions. Although this is a modest effect size, given the magnitude of weight lost prior to study entry, a higher rate of weight loss maintenance among Guided participants has potential to confer important health benefits.(Lefevre et al., 2009; Wing et al., 2011) Moreover, Self-Directed participants received similar intervention content (i.e., Keep It Off workbook) and participated in two phone coaching calls. Thus, the group difference may have been attenuated relative to the inclusion of a no treatment control group.

The majority of studies focused on enhancing weight loss maintenance have started out with an initial weight loss phase, including the Weight Loss Maintenance Trial, the largest multi-site trial with an explicit focus on weight loss maintenance.(Svetkey et al., 2008) We are aware of only one published randomized controlled trial that has evaluated the efficacy of maintenance-focused programs for adults who had recently lost weight prior to study entry.(Wing et al., 2006) Similar to the Keep It Off study, Wing et al recruited participants who had lost at least 10% of their body weight, however, in the STOP Regain trial, the weight loss could have occurred over the past two years whereas, Keep It Off participants were required to have lost the weight in the prior year. Although the intervention content and messages in the two studies had many commonalities, the treatment modalities were unique. STOP Regain included a less intensive control group which received only quarterly newsletters, an internet-based intervention group, and a face-to-face intervention group. Another important difference was the length of follow-up; 18 months in the STOP Regain trial and 24 months in the current trial. Despite these differences, results of the two trials are strikingly similar. The amount of weight gain observed in the Keep It Off Self-Directed group and the STOP Regain control group and internet group were similar (i.e., about 10 pounds), as was the weight regain observed in the Keep It Off Guided and STOP Regain face-to-face groups (i.e., about 5 pounds). Although the absolute number of STOP Regain participants who were classified as successful maintainers was higher, the pattern of results was quite similar, with the Keep It Off Guided participants and the STOP Regain internet and face-to-face participants more likely to be successful relative to the Keep It Off Self-Directed and STOP Regain control participants. These data suggest that a phone-based intervention may be a convenient and potentially less costly, but comparable alternative to a face-to-face maintenance intervention and are consistent with results from two recent trials that have directly compared weight loss and maintenance interventions delivered via in-person sessions versus remotely, primarily using phone-based support. (Appel et al., 2011; Perri et al., 2008) An important question to address is whether there are prognostic indicators for treatment outcome, including early markers of poor outcome, and whether alternative strategies could be used to enhance outcomes among groups at highest risk for regain.

Study strengths included high retention and intervention participation rates in both intervention arms. Limitations included the availability of only self-report weight data at six and 18 month follow-up and self-report measures of dietary intake and physical activity that were not sensitive to change. Moreover, the study sample included primarily health plan members with higher education levels, limiting generalizability of study findings. However, the use of health plan members suggests a potential practical venue for dissemination. Also, the method used for imputing data in this (and previous) studies yielded artificially low estimates of variability in the primary outcome(Rubin, 1987), as missing weights were replaced with measures of central tendency. While it appears that this method yields less bias than a complete-cases only analysis, we recommend that future studies in this area use multiple imputation methods that include random error to reduce central tendency bias in the imputed data in conjunction with a sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of potential non-random missingness on the modeled estimates.

Despite these limitations, these results suggest that recruiting participants after they have lost weight and offering a maintenance-focused intervention may be an effective strategy for improving long-term weight loss maintenance. Future research should focus on strategies to enhance the efficacy of such interventions and to identify the optimal intervention intensity and modality for different subgroups of individuals who are at highest risk for regain.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Innovative strategies are needed to address the perennial problem of weight regain.

Recruiting participants after they have lost weight may be an effective strategy.

Keep It Off examined the efficacy of a maintenance program for recent weight losers.

The Keep It Off phone-based approach increases potential for dissemination.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA128211). The project was initiated and analyzed by the study investigators. This manuscript represents original work. All authors have contributed to and approved the manuscript and this material has not been published nor is it under consideration for publication at any other journal or electronic media.

Footnotes

Study concept and design: Sherwood, Crain, Martinson, Hayes, Jeffery

Acquisition of data: Sherwood, Crain, Martinson, Hayes, JD Anderson

Analysis and interpretation of data: Sherwood, Crain, Martinson, CP Anderson, Senso, Jeffery

Drafting of the manuscript: Sherwood, Crain, CP Anderson

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Sherwood, Crain, Martinson, CP Anderson, Hayes, JD Anderson, Senso, Jeffery

Statistical analysis: Crain, CP Anderson

Obtained funding: Sherwood, Crain, Martinson, Jeffery

Final approval of the version to be published: Sherwood, Crain, Martinson, CP Anderson, Hayes, JD Anderson, Senso, Jeffery

Human Participation Protection

This study was reviewed and approved by the HealthPartners Institutional Review Board. The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00702455 http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00702455?term=Keep+rIt+rOff&rank=1

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andersen PK, Gill RD. Cox’s Regression Model for Counting Processes: A Large Sample Study. The Annuals of Statistics. 1982;10:1100–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Appel LJ, Clark JM, Yeh HC, Wang NY, Coughlin JW, Daumit G, Miller ER, 3rd, Dalcin A, Jerome GJ, Geller S, Noronha G, Pozefsky T, Charleston J, Reynolds JB, Durkin N, Rubin RR, Louis TA, Brancati FL. Comparative effectiveness of weight-loss interventions in clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1959–1968. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson ME, Charlson RE, Peterson JC, Marinopoulos SS, Briggs WM, Hollenberg JP. The Charlson comorbidity index is adapted to predict costs of chronic disease in primary care patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:1234–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry SJ, McBride C, Grothaus LC, Louie D, Wagner EH. A randomized trial of self-help materials, personalized feedback, and telephone counseling with nonvolunteer smokers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:1005–1014. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.6.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eakin E, Reeves M, Lawler S, Graves N, Oldenburg B, Del Mar C, Wilke K, Winkler E, Barnett A. Telephone counseling for physical activity and diet in primary care patients. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J, French S, Jeffery R, McGovern P, Wing R. Dietary and physical activity correlates of long-term weight loss. Obes Res. 1994;2:307–313. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1994.tb00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery RW, Drewnowski A, Epstein LH, Stunkard AJ, Wilson GT, Wing RR, Hill DR. Long-term maintenance of weight loss: current status. Health Psychol. 2000;19:5–16. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.suppl1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery RW, Kelly KM, Rothman AJ, Sherwood NE, Boutelle KN. The weight loss experience: a descriptive analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2004;27:100–106. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2702_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery RW, Wing RR, Sherwood NE, Tate D. Physical activity and weight loss: Does prescribing higher physical activity goals improve outcome? American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2003;78:669–670. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.4.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery RW, Wing RR, Thorson C, Burton LR, Raether C, Harvey J, Mullen M. Strengthening behavioral interventions for weight loss: a randomized trial of food provision and monetary incentives. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:1038–1045. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klem ML, Wing RR, McGuire MT, Seagle HM, Hill JO. A descriptive study of individuals successful at long-term maintenance of substantial weight loss. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66:239–246. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/66.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefevre M, Redman LM, Heilbronn LK, Smith JV, Martin CK, Rood JC, Greenway FL, Williamson DA, Smith SR, Ravussin E. Caloric restriction alone and with exercise improves CVD risk in healthy non-obese individuals. Atherosclerosis. 2009;203:206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy RL, Jeffery RW, Langer SL, Graham DJ, Welsh EM, Flood AP, Jaeb MA, Laqua PS, Finch EA, Hotop AM, Yatsuya H. Maintenance-tailored therapy vs. standard behavior therapy for 30-month maintenance of weight loss. Prev Med. 2010;51:457–459. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paffenbarger R, Wing A, Hyde R. Physical activity as an index of heart attack risk in college alumni. Am J Epidemiol. 1978;108:161–175. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perri MG, Limacher MC, Durning PE, Janicke DM, Lutes LD, Bobroff LB, Dale MS, Daniels MJ, Radcliff TA, Martin AD. Extended-care programs for weight management in rural communities: the treatment of obesity in underserved rural settings (TOURS) randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2347–2354. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.21.2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perri MG, McAdoo WG, Spevak PA, Newlin DB. Effect of a multicomponent maintenance program on long-term weight loss. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1984a;52:480–481. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.3.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perri MG, Nezu AM, McKelvey WF, Shermer RL, Renjilian DA, Viegener BJ. Relapse prevention training and problem-solving therapy in the long-term management of obesity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:722–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perri MG, Nezu AM, Patti ET, McCann KL. Effect of length of treatment on weight loss. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57:450–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perri MG, Shapiro RM, Ludwig WW, Twentyman CT, McAdoo WG. Maintenance strategies for the treatment of obesity: an evaluation of relapse prevention training and posttreatment contact by mail and telephone. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1984b;52:404–413. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman AJ. Toward a theory-based analysis of behavioral maintenance. Health Psychol. 2000;19:64–69. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.suppl1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation of Nonresponses in Survey Data. Wiley; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sarwer DB, von Sydow Green A, Vetter ML, Wadden TA. Behavior therapy for obesity: where are we now? Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2009;16:347–352. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e32832f5a79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood NE, Crain AL, Martinson BC, Hayes MG, Anderson JD, Clausen JM, O’Connor PJ, Jeffery RW. Keep it off: a phone-based intervention for long-term weight-loss maintenance. Contemp Clin Trials. 2011;32:551–560. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood NE, Jeffery RW, Pronk NP, Boucher JL, Hanson A, Boyle R, Brelje K, Hase K, Chen V. Mail and phone interventions for weight loss in a managed-care setting: weigh-to-be 2-year outcomes. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30:1565–1573. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood NE, Jeffery RW, Welsh EM, Vanwormer J, Hotop AM. The drop it at last study: six-month results of a phone-based weight loss trial. Am J Health Promot. 2010;24:378–383. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.080826-QUAN-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer EA, Appleby PN, Davey GK, Key TJ. Validity of self-reported height and weight in 4808 EPIC-Oxford participants. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:561–565. doi: 10.1079/PHN2001322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subar AF, Thompson FE, Kipnis V, Midthune D, Hurwitz P, McNutt S, McIntosh A, Rosenfeld S. Comparative validation of the Block, Willett, and National Cancer Institute food frequency questionnaires: the Eating at America’s Table Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:1089–1099. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.12.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svetkey LP, Stevens VJ, Brantley PJ, Appel LJ, Hollis JF, Loria CM, Vollmer WM, Gullion CM, Funk K, Smith P, Samuel-Hodge C, Myers V, Lien LF, Laferriere D, Kennedy B, Jerome GJ, Heinith F, Harsha DW, Evans P, Erlinger TP, Dalcin AT, Coughlin J, Charleston J, Champagne CM, Bauck A, Ard JD, Aicher K. Comparison of strategies for sustaining weight loss: the weight loss maintenance randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1139–1148. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate DF, JR, Sherwood NE, Wing RR. Long-term weight losses associated with prescription of higher physical activity goals. Are higher levels of physical activity protective against weight regain? Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:954–959. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.4.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Writing Group for the Activity Counseling Trial Research Group. Effects of Physical Activity Counseling in Primary Care: The Activity Counseling Trial: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2001;286:677–687. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.6.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson FE, Subar AF, Brown CC, Smith AF, Sharbaught CO, Jobe JB, Mittl B, Gibson JT, Ziegler RG. Cognitive research enhances accuracy of food frequency questionnaire report: results of an experiment validatin study. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2002;102:212–225. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing R, Jeffery R, Hellerstedt W, Burton L. Effect of frequent phone contacts and optional food provision on maintainence of weight loss. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1996;18:172–176. doi: 10.1007/BF02883394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing RR, Lang W, Wadden TA, Safford M, Knowler WC, Bertoni AG, Hill JO, Brancati FL, Peters A, Wagenknecht L. Benefits of modest weight loss in improving cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1481–1486. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing RR, Tate DF, Gorin AA, Raynor HA, Fava JL. A self-regulation program for maintenance of weight loss. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1563–1571. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.