Abstract

This study examines semantic development in 60 Spanish-English bilingual children, ages 7 years 3 months to 9 years 11 months, who differed orthogonally in age (younger, older) and language experience (HEE: higher English experience, HSE: higher Spanish experience). Children produced three associations to 12 pairs of translation equivalents. Older children produced more semantic responses and code-switched more often from Spanish to English than younger children. Within each group, children demonstrated better performance in the more frequently used than the less used language. The HEE children outperformed the HSE children in English and the HSE children outperformed the HEE children in Spanish. These effects of age and language experience are consistent with predictions of the Revised Hierarchical Model of bilingual lexical organization.

The increasing representation of bilingual students in US schools (McCardle & Leung, 2006) calls for more information on the normative course of bilingual language development. One domain of language that shows the greatest growth in school-age children is vocabulary. A rich vocabulary is essential for smooth and functional communication. During the school years, children are increasingly called upon to produce word definitions and to use words in various oral and written discourses. These academic tasks require deep knowledge of words such as categorical and functional information, grammatical class information, and knowledge of morphological variations of words and of the sociolinguistic contexts of word usage. Despite the importance of deep vocabulary knowledge, we know very little about its development among bilingual children. In this study, we aimed to remedy this gap in the literature.

In addition to their practical significance, studies of bilingual children can be used to test theoretical models of bilingual language production and lexical-semantic representation that are largely based on adult data. We conducted the present study using the framework of the Revised Hierarchical Model (Kroll, Michael, Tokowicz, & Dufour, 2002; Kroll & Stewart, 1994), a prominent model of bilingual word production and lexical organization. In the following section we provide a description of the model and a review of literature on bilingual lexical-semantic development and elaborate on our goals.

The Revised Hierarchical Model (RHM) and Its Application to Bilingual Children

The RHM (Kroll et al., 2002; Kroll & Stewart, 1994; Kroll, van Hell, Tokowicz, & Green, 2010) posits three important assumptions about the bilingual lexicon. First, bilinguals have a single, shared conceptual store and two separate word-form lexicons for their two languages (L1 and L2). Second, the location, number, and direction of links among the three storage systems vary depending on the individual’s L1 and L2 experience. In the early stage of L2 learning, direct links between conceptual representation and the L2 lexicon are missing and speakers gain access to concepts through the mediation of the L1 lexicon. As learners achieve higher proficiency in the L2, they develop direct links between the L2 lexicon and concepts and eliminate the need to mediate through the L1. However, the link between L2 words and concepts is weaker than that between L1 words and concepts. Third, there are weighted bidirectional links between the L1 and L2 lexicon with stronger connections from L2 to L1 words than the reverse. Finally, although the RHM was originally proposed to depict lexical organization in sequential bilinguals (those who learn an L2 at a later age well after the L1 is acquired), it also takes into consideration the dynamic nature of bilingual proficiency and suggests that shifts in language dominance may result in asymmetric processing in favor of the L2 (Kroll et al., 2010).

Since its inception, the RHM has been the focus of numerous studies examining various aspects of the model, such as the asymmetry between L1 and L2 processing, the consequence of language learning history for lexical processing (the developmental hypothesis), and the common conceptual system assumption. These studies have employed a number of experimental paradigms (e.g., translation, picture naming, list recall, brainstorming, lexical decision) and addressed various phenomena such as cross-language priming/interference, cognate advantage in early phases of L2 learning, and frequency and outcomes of code switching. Although the utility of this model has recently been under scrutiny, it remains one of the most influential and current models of bilingual memory (Brysbaert & Duyck, 2010; Brysbaert, Verreyt, & Duyck, 2010; Kroll et al., 2010). Despite the impressive amount of research inspired by this model, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have tested this model using data from bilingual children. Unlike bilingual adults who have a firmly-established L1 system or sometimes two equally well-established language systems, young bilingual children, regardless of age of L2 onset, are still in the process of acquiring two languages. A valid model of bilingual memory must be applicable to a broad range of bilinguals including both adults and children. In the present study, we set out to test the model using data from a heterogeneous group of bilingual children. In particular, we focused on the developmental aspect and the asymmetric processing aspect of the model and examined the effects of age and language experience on bilingual children’s semantic performance.

Lexical-Semantic Development in Spanish-English Bilingual Children

Extant research suggests that Spanish-English bilingual children raised in the United States show rapid gains in the number of entries in their English vocabulary (breadth of vocabulary) during preschool and school-age years such that the gap between the bilingual children’s standardized vocabulary scores and monolingual English norms gradually closes (Cobo-Lewis, Pearson, Eilers, & Umbel, 2002; Hammer, Lawrence, & Miccio, 2008; Rodríguez, Díaz, Duran, & Espinosa, 1995; Winsler, Díaz, Espinosa, & Rodríguez, 1999). At the same time, although there are no decrements in Spanish vocabulary, there is a deceleration in growth for the minority or less used language (Kohnert & Bates, 2002; Kohnert, Bates, & Hernandez, 1999). Eventually it is this process that leads the second language to become the dominant language.

While these previous studies utilized measures of vocabulary breadth (e.g., the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test – III, Dunn & Dunn, 1997) (Hammer et al., 2008; Rodríguez et al., 1995; Winsler et al., 1999) and lexical processing (speed and accuracy of picture naming and picture identification, Kohnert & Bates, 2002; Kohnert et al., 1999), information regarding vocabulary depth development in bilingual children is scarce. Research in monolingual children suggests that in contrast to vocabulary breadth, which expands quickly in preschool and school age years, the accumulation of deep vocabulary knowledge takes a prolonged period of time and repeated exposures to words in a language (Bloom, 2000; Carey & Bartlett, 1978). For example, Johnson and Anglin (1995) estimated that between 1st and 5th grades, vocabulary size of a monolingual child increased by 30,000 words if measured on the basis of receptive vocabulary. In contrast, the increase was only about 5,000 words when a stringent criterion of high-quality definitions was used. For a bilingual child, gaining vocabulary depth involves learning two sets of words and the semantic and collocational features that characterize and bond each set. Because input is distributed across two languages, bilingual children have less input in each of their two languages which makes this task even more challenging (Gollan, Montoya, Cera, & Sandoval, 2008; Vermeer, 2001).

A vocabulary depth measure that has been used with both monolingual and bilingual children is the word association task. In this task, the participant responds with the first word that comes to mind upon hearing a stimulus. Previous studies that utilized this task suggested a shift in word association responses from idiosyncratic or sound-based (rhyming) in the preschool years, to primarily syntagmatic (e.g., functional, descriptive, syntactic) in kindergarteners and first-graders, to increasingly paradigmatic (categorical, synonymous, antonymous) by the time children are about 9 years of age (Entwisle, 1966; Nelson, 1977; Sheng & McGregor, 2010; Sheng, McGregor, & Marian, 2006; Sheng, Peña, Bedore, & Fiestas, in press). This change in semantic organization principles may be associated with changes in children’s conceptual organization, changes in children’s interpretation of the task as a result of schooling, the expansion of vocabulary, and the development of reading (Cronin, 2002; Hashimoto, McGregor, & Graham, 2007; Nelson, 1977). In the current study, we used a variant of the word association task with school-aged bilingual children to gain insights into the types of changes in semantic structures as well as the factors that drive these changes.

The Current Study

Guided by the RHM of bilingual word production, we examined the development of semantic depth in Spanish-English bilingual students. Children participated in a repeated word association task and generated three responses to Spanish and English translation equivalents. There were three objectives. First, we aimed to examine age-related changes in the depth of word knowledge between the early to middle elementary school years. This age period was interesting because children are faced with rapidly increasing demands of both listening and reading comprehension, which makes the enrichment of semantic networks a pressing task (Nippold, 2007). Second, we aimed to investigate the effect of language learning experience on the development of semantic depth. Third, because there are developmental changes in specific kinds of semantic relations (i.e., the syntagmatic-paradigmatic shift; Nelson, 1977), we explored the effect of age and language experience on the use of paradigmatic and syntagmatic semantic relations.

With regard to age, we hypothesized that older children would have greater semantic depth than younger children. This age advantage would be manifested as larger numbers of semantic responses and fewer errors. We were also interested in the degree of age-related difference across the bilinguals’ two languages. On the one hand, because previous studies with Spanish-English bilinguals suggested more rapid vocabulary learning in English, we may expect a larger age-related difference in English semantic responses than in Spanish. On the other hand, because vocabulary depth develops slowly, the difference between age groups may be modest and comparable in English and Spanish. Similarly, if the shift toward paradigmatic semantic organization represents a more conceptual than strictly linguistic development, there may be little difference across languages.

With regard to experience, we hypothesized that in keeping with the RHM, the amount of language experience would affect the depth of semantic knowledge, resulting in an asymmetry in semantic depth between a bilingual’s more and less frequently used languages. In other words, we anticipated an interaction between test language and experience group such that the bilingual children who had more experience using Spanish would generate more semantic responses in Spanish than in English whereas the children who had more experience using English would generate more semantic responses in English than Spanish. By the same token, we predicted that unbalanced bilingual language experience may result in asymmetry in the direction, frequency, and success rate of code switches. Specifically, children would be more likely to switch from their less used language to their more frequently used language. We also predicted that code-switched responses would be mostly successful such that they would be related in meaning to the cross-language targets.

With regard to the use of specific kinds of semantic relations, because syntagmatic relations are earlier emerging and well-established by first grade (Entwisle, 1977; Sheng et al., 2006), we anticipated greater age-related increase in paradigmatic semantic knowledge in the current pool of participants. Also, we expected paradigmatic semantic knowledge to be shallow such that responses of this type would diminish across repeated elicitation.

Method

Participants

Participants were selected from a pool of 280 participants in a large on-going study of semantic and syntactic development in children acquiring Spanish and English in bilingual environments. Participants were recruited from school districts in central Texas and Colorado, which enroll large numbers of Spanish English bilingual students. To confirm that the children had typically developing language skills children’s caregivers rated their child’s language performance across domains (e.g., vocabulary, grammar, comprehension) on a five-point scale (1 = low proficiency; 5 = high proficiency) in each language. Because bilingual children often exhibit unbalanced proficiency in their two languages, we used caregiver ratings of children’s stronger language to determine eligibility. To qualify for this study, children had to have received average ratings (across domains) above the cut points of 4.5 for Spanish or 3.9 for English in their stronger language. Cut scores were derived empirically using a discriminant function analysis comparing children with and without language impairment (Peña, Gutiérrez-Clellen, Iglesias, Goldstein, & Bedore, in development). Narrative language samples in both languages were used to confirm typical language ability. Grammaticality in story production was 80% or above in children’s stronger language (based on Gutiérrez-Clellen & Kreiter, 2003; Restrepo, 1998).

Sixty children were selected to form four equal-sized groups varying orthogonally in age and language experience. There were two groups of younger children, ages 7 years 3 months to 8 years 4 months, and two groups of older children, aged 8 years 7 months to 9 years 11 months. We used current language use to index language experience. Each child’s primary caregiver was interviewed to obtain an hour-by-hour account of the child’s language use, detailing the conversational partner(s) and language of use in both input and output modalities during each waking hour of a typical weekday and a typical weekend day (Gutiérrez-Clellen & Kreiter, 2003; Peña, et al., in development). Based on caregiver reports, an average language use value was derived which represented the percent of time a child used (averaged across input and output) English and Spanish. Because our focus was on children who had different amount of experience in L1 and L2, those who had relatively balanced use of the two languages (45% – 55%) were excluded. Among the four groups of participants, two groups (one younger, one older) were categorized as having higher English experience (HEE) (range of English use = 56% –86%) and the other two higher Spanish experience (HSE) (range of English use = 8% –44%). Only one child had a low English use of 8%; all other children used English at least 13% of the time. To recap, each child had an age match (within 5 months) who had the inverse amount of language use. For example, a child who used English 65% of the time and Spanish 35% of the time was matched to a child of comparable age who used Spanish 65% of the time and English 35% of the time. Each child also had a language use match from the other age group (i.e., younger HEE with older HEE). Language use was matched within 12%.

Table 1 provides a summary of the characteristics and language history of the 4 groups: younger children with higher English experience (Y-HEE), younger children with higher Spanish experience (Y-HSE), older children with higher English experience (O-HEE), and older children with higher Spanish experience (O-HSE). Chronological age differed significantly between the two HEE groups, t (28) = 11.11, p < .001, d = 4.06; and between the two HSE groups, t (28) = 11.97, p < .001, d = 4.37. English (and Spanish) language use differed significantly between the two younger groups, t (28) = 11.81, p < .001, d = 4.31, and between the two older groups, t (28) = 11.97, p < .001, d = 3.86. Moreover, chronological age was matched within the two younger groups, t (28) = .85, p = .41; and the two older groups, t (28) = .35, p = .73. Likewise, language use was matched within the two HEE groups, t (28) = .35, p = .73, and the two HSE groups, t (28) = .36, p = .72.

Table 1.

Participant Information Presented in Means (SDs) and Ranges

| Group | Age in months | Sex | Bilingual type | Current English use | Age of English onset (in years) | Number of years learning English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y-HEE | 94.40 (4.48) 87–100 |

8F, 7M | 5 SEQ;10 SIM | 68% (7.8%) 56–83% |

2.27 (1.94) 0–6 |

5.60 (2.10) 1.50–8.33 |

| Y-HSE | 93.13 (3.68) 87–97 |

9F, 6M | 13 SEQ;2 SIM | 33% (8.5%) 13–46% |

3.87 (1.68) 0–6 |

3.89 (1.79) 1.75–8.08 |

| O-HEE | 112.60 (4.48) 103–119 |

8F, 7M | 10 SEQ;5 SIM | 69% (8.7) 56–86% |

4.00 (2.42) 0–8 |

5.38 (2.32) 1.25–9.25 |

| O-HSE | 112.00 (4.87) 104–119 |

8F, 7M | 11 SEQ;4 SIM | 31% (10.7%) 8–44% |

4.20 (1.57) 0–6 |

5.13 (1.30) 3.58–8.67 |

Note.

Y-HEE = Younger-Higher English Experience; Y-HSE = Younger-Higher Spanish Experience; O-HEE = Older-Higher English Experience; O-HSE = Older-Higher Spanish Experience. F = Female; M = Male. SEQ = Sequential bilingual with English onset at age 4 or older. SIM = Simultaneous Bilingual with English onset at birth to 3.

While all the children began to acquire Spanish from birth, they differed in the age of onset of English acquisition. Among the 60 children, 21 were simultaneous bilinguals (age of English onset between birth and 3), the remaining 39 were sequential bilinguals (age of English onset at 4 or after) (Patterson & Pearson, 2004). As seen in Table 1, the Y-HEE group included a larger number of simultaneous bilinguals than all other groups. The Y-HEE group had a younger mean age of English onset than the Y-HSE, t (28) = 2.41, p = .02, d = .88, the O-HEE, t (28) = 2.16, p = .04, d = .79, and the O-HSE groups, t (28) = 3.00, p = .006, d = 1.09; the latter three groups did not differ from each other, ts < 1, ps > .5. Conversely, the Y-HSE group had shorter experience learning English than the Y-HEE, t (28) = 2.39, p = .02, d = .87, the O-HEE, t (28) = 1.97, p = .06, d = .72, and the O-HSE groups, t (28) = 2.17, p = .04, d = .79; the latter three groups did not differ from each other, ts < 1, ps > .47.

Of the 60 participants, 53 received free or reduced lunch through the free lunch program, 7 did not receive a free or reduced lunch. Fifty-five of the children were Hispanic as indicated by the parents. The remaining parents did not indicate their child’s race or ethnicity.

Stimuli

As shown in Table 2, the stimuli included 12 pairs of English and Spanish translation equivalents, distributed evenly across the adjective, noun, and verb classes. Words were selected after examining concepts for the target grades (grades 1 to 3) in the Texas Department of Education curriculum guidelines. All the words were curriculum targets. The words were of comparable frequency of occurrence in English and Spanish, based on the Corpus of Contemporary American English (Davies, 2008) and Corpus Del Español (Davies, 2002). The stimuli belonged to the themes of animal, food, weather, and exercising, all of which were likely to be familiar to school-age bilingual children.

Table 2.

Frequency of Occurrence of the Stimuli

| English Word | Frequencya | Spanish Word | Frequencyb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delicious | 1.9 | Delicioso | 1.6 |

| Frozen | 10.1 | Congelado | 1.2 |

| Furry | 0.2 | Peludo | 0.2 |

| Nutritious | 1.3 | Nutritivo | 4.6 |

| Dinner | 15.1 | Cena | 9.4 |

| Forest | 115.2 | Bosque | 172.2 |

| Soup | 4.4 | Sopa | 1.6 |

| Summer | 80.2 | Verano | 82.4 |

| Eating | 68.5 | Comiendo | 48.6 |

| Growling | 0.6 | Grunir | 0.8 |

| Stretching | 25.1 | Estirar | 8 |

| Wearing | 67.4 | Vestirse | 40.2 |

| Mean (SD) | 32.50 (39.60) | Mean (SD) | 30.90 (51.50) |

Note.

Occurrences per million of the lemma form in academic contexts (Davies, 2008).

Occurrences per million of the lemma form in academic contexts (Davies, 2002).

Procedures

The repeated word association task was administered to children in Spanish and in English on two separate days, with order of test language counterbalanced. The English verbs were presented in the present progressive form (-ing), the Spanish verbs were presented in the infinitive form. The task begins with a short practice with the words car [carro] and run [correr]. The children were instructed to respond with a word that goes with the target word. The target word was presented three times consecutively to elicit three different responses. The examiner provided a visual cue to the child by keeping track of each response with fingers. To encourage children to produce various kinds of semantic responses, the examiner reinforced any semantic responses produced by the child (e.g., car-drive [carro-manejar]) and offered a model of paradigmatic response (a response that belongs to the same semantic category and grammatical class) by saying “Yes, drive goes with car, and another word is truck [camioneta]” if the child did not produce this type of responses spontaneously during practice. In the second elicitation, an additional paradigmatic response model (transportation [transportación]) was offered if necessary. For the target run, the words jump [brincar] and exercise [ejercicio] were offered as alternate examples when necessary. The decision to integrate paradigmatic response models during practice was motivated by developmental data indicating the late emergence of this response type (Nelson, 1977). The stimulus words were randomized with the stipulation that words belonging to the same theme (e.g., eat and dinner) did not occur next to each other. Words were randomized respectively in English and in Spanish and presented in the same order across participants. The examiner wrote down the child’s responses verbatim on a scoring form. All sessions were audio-recorded.

Coding

Word association responses were coded into two main categories: semantic or erroneous. Semantic responses were further categorized as paradigmatic and syntagmatic. Paradigmatic responses encompass synonyms (e.g., delicious-scrumptious; delicioso-rico [delicious-tasty]; growling-screaming; gruñir-ladrar [to growl-to bark]), antonyms (e.g., nutritious-poisonous, peludo-pelón [furry-bald]), and words that share categorical (e.g., dinner-meal; sopa-comida [soup-food]; forest-jungle; bosque-playa [forest-beach]) relations with the stimuli. Syntagmatic responses include words that bear non-categorical semantic relations such as functional (e.g., dinner-eat; vestirse-ropa [get dressed-clothing]), attributive (e.g., furry-lion; peludo-perro [furry-dog]), locative (e.g., dinner-restaurant), or thematic (e.g., summer-vacation; cena-familia [dinner-family]) relations with the stimulus. Errors include no responses, repetitions of the stimuli or of earlier responses, responses that share sound similarities with the stimuli (e.g., growling-drowling; estirar-estresando [stretching-stressing]), translations (e.g., dinner-cena), words that were unrelated (e.g., frozen-bus), repetitions, or non-words (e.g., cena-detruir [dinner-non word]). Code switched responses received a primary error code. Because we were interested in the potential benefits of code switching, a secondary code was attached to indicate whether the code switched response led to a semantic response.

Reliability

A fluent bilingual research assistant coded all data. A second bilingual research assistant randomly selected 14 samples in English and 15 samples in Spanish and coded them independently. Point-to-point agreement in English averaged at 90% and ranged from 80% to 96%. Point-to-point agreement in Spanish averaged at 92% and ranged from 85% to 100%.

Results

Semantic Responses

Proportions of semantic responses (paradigmatic and syntagmatic combined) for different groups, languages, and trials are presented in Table 3. A mixed-model ANOVA was conducted in which age group (younger, older) and experience group (HEE, HSE) were the between-participant factors, test language (English, Spanish) and elicitation trial (trials 1, 2, 3) were within-participant factors, and the proportion of semantic responses (excluding code switches) was the dependent measure. All significant main effects and interaction were followed with post-hoc tests with Bonferroni corrections. All significance tests were two-tailed.

Table 3.

Mean Proportions (Standard Deviations) of Semantic, Paradigmatic, and Syntagmatic Responses as a Function of Group and Trial

| English | Spanish | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 3 | All | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 3 | All | |

| Y-HEE | ||||||||

| Semantic | .71 (.21) | .69 (.22) | .55 (.23) | .65 (.20) | .52 (.28) | .40 (.29) | .34 (.24) | .42 (.25) |

| Paradigmatic | .33 (.22) | .24 (.20) | .19 (.16) | .25 (.18) | .20 (.20) | .09 (.10) | .08 (.12) | .12 (.12) |

| Syntagmatic | .38 (.24) | .45 (.29) | .36 (.26) | .39 (.25) | .32 (.25) | .31 (.24) | .26 (.23) | .30 (.23) |

| Y-HSE | ||||||||

| Semantic | .47 (.28) | .43 (.22) | .38 (.25) | .43 (.23) | .73 (.20) | .62 (.23) | .54 (.23) | .63 (.21) |

| Paradigmatic | .22 (.21) | .17 (.16) | .09 (.10) | .16 (.14) | .33 (.15) | .21 (.16) | .14 (10) | .23 (.11) |

| Syntagmatic | .25 (.20) | .26 (.18) | .29 (.23) | .27 (.17) | .39 (.23) | .40 (.24) | .40 (.19) | .40 (.21) |

| O-HEE | ||||||||

| Semantic | .83 (.16) | .71 (.18) | .52 (.28) | .69 (.19) | .65 (.29) | .59 (.30) | .47 (.28) | .57 (.27) |

| Paradigmatic | .42 (.23) | .33 (.23) | .18 (.18) | .31 (.20) | .28 (.23) | .22 (.19) | .12 (.13) | .21 (.17) |

| Syntagmatic | .41 (.19) | .38 (.23) | .34 (.23) | .38 (.20) | .37 (.25) | .37 (.28) | .34 (.27) | .36 (.25) |

| O-HSE | ||||||||

| Semantic | .65 (.27) | .61 (.24) | .52 (.25) | .59 (.23) | .82 (.16) | .77 (.19) | .67 (.15) | .75 (.15) |

| Paradigmatic | .29 (.19) | .23 (.18) | .17 (.13) | .23 (.14) | .46 (.14) | .28 (.15) | .19 (.12) | .31 (.11) |

| Syntagmatic | .36 (.23) | .38 (.20) | .36 (.24) | .36 (.18) | .36 (.15) | .49 (.18) | .48 (.14) | .44 (.12) |

Note.

Y-HEE = Younger-Higher English Experience; Y-HSE = Younger-Higher Spanish Experience; O-HEE = Older-Higher English Experience; O-HSE = Older-Higher Spanish Experience.

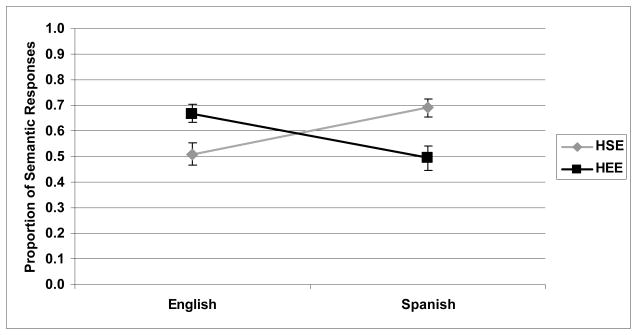

There was a main effect of age, F (1, 56) = 6.90, p = .01, ηp2= .11. The older children (M = .65, SE = .032) generated more semantic responses than the younger children (M = .53, SE = .032). There was a main effect of trial, F (2, 112) = 57.71, p < .001, ηp2= .51. The proportion of semantic responses decreased from trial 1 (M = .67, SE = .023) to trial 2 (M = .60, SE = .025) and from trial 2 to trial 3 (M = .50, SE = .026), ps < .001. There was an interaction between test language and experience group, F (1, 56) = 27.04, p < .001, ηp2 =.33. As illustrated in Figure 1, the HSE groups produced more semantic responses in Spanish (M = .69, SE = .041) than English (M = .51, SE = .039) tasks, p = .003; whereas the HEE groups produced more semantic responses in English (M = .67, SE = .039) than Spanish (M = .49, SE = .041), p = .004. Further, when tested in Spanish, the HSE groups produced more semantic responses than the HEE groups, p = .005; when tested in English, the HEE groups produced more semantic responses than the HSE groups, p = .04. The three way interaction among age, test language, and experience group was not significant, F (1, 56) = 1.23, p = .27.

Figure 1.

Proportion of semantic responses by test language and experience group. Bars denote standard errors. HEE = Higher English Experience. HSE = Higher Spanish Experience.

Subtypes of Semantic Responses

To examine the specific kinds of semantic relations that make up children’s vocabulary, we ran two additional ANOVAs with age, experience, language, and trial as independent variables and proportion of paradigmatic and syntagmatic responses as the respective dependent measure (see Table 3 for means).

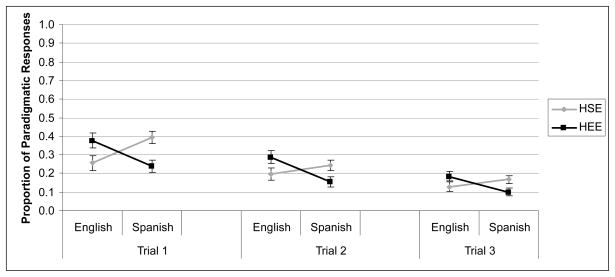

Four significant effects surfaced when comparing paradigmatic responses. First, the age effect was significant, F (1, 56) = 5.34, p = .02, ηp2 =.09, with older children (M = .26, SE = .022) producing more paradigmatic responses than younger children (M = .19, SE = .022). Second, the effect of trial was significant, F (2, 112) = 82.60, p < .001, ηp2 =.60, as paradigmatic responses decreased from trial 1 (M = .32, SE = .020) to trial 2 (M =.22, SE =.018), and from trial 2 to trial 3 (M =.15, SE =. 013), ps < .001. Third, there was an interaction between test language and experience group, F (1, 56) = 20.62, p < .001, ηp2 =.27. This interaction was modified by a fourth three-way interaction among test language, experience group, and trial, F (1, 112) = 3.69, p = .03, ηp2 =.06. Planned t-tests showed that for the HSE groups, Spanish words elicited more paradigmatic responses than English words at trial 1 (p = .004), but not trials 2 and 3; for the HEE groups, English words elicited more paradigmatic responses than Spanish words in all three trials, ps < .02. When tested in Spanish, the HSE groups produced more paradigmatic responses than the HEE groups in all three trials, ps ≤ .03; when tested in English; the HEE groups produced more paradigmatic responses than the HSE groups only at trial 1, p = .03. These patterns are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Proportion of paradigmatic responses by test language, experience group, and trial. Bars denote standard errors. HEE = Higher English Experience. HSE = Higher Spanish Experience.

Comparisons of syntagmatic responses revealed a significant interaction between test language and experience group, F (1, 56) = 10.11, p = .002, ηp2 =.15. Post-hoc tests indicated a significant difference in the HSE children’s Spanish (M = .42, SE = .038) and English (M = .32, SE = .037) performance, p = .03; no other pair-wise comparisons were significant (see Figure 3). There was also a marginally significant interaction between trial and experience group, F (2, 112) = 3.13, p = .048, ηp2 =.05. There was a trend for the HEE children to produce more syntagmatic responses in trial 2 (M = .38, SE = .042) than trial 3 (M = .33, SE = .040), however, post-hoc comparisons indicated that this difference did not reach statistical significance, p =.08.

Figure 3.

Proportion of syntagmatic responses by test language and experience group. Bars denote standard errors. HEE = Higher English Experience. HSE = Higher Spanish Experience.

Code Switches

Table 4 shows the occurrence of code switches in children’s responses. There was a significant relationship between test language and group, χ2(3) = 59.78, p < .001. A follow-up test within each language was conducted. Fishers exact test demonstrated no difference across the four groups when code switching from English to Spanish. Comparisons of groups by age and language experience using a Pearson chi-square indicated that HEE children and older children were more likely to code switch from Spanish to English, χ2 (1) = 6.82, p = .009. The effect size (Cramer’s V) was .170.

Table 4.

Percent Code Switches as a Function of Group and Language

| English→Spanish | Spanish→English | |

|---|---|---|

| Y-HEE | 0.2% (1 attempt) 100% success |

14% (72 attempts), 63% success |

| Y-HSE | 0.7% (4 attempts) 50% success |

2.4% (13 attempts) 69% success |

| O-HEE | 0.2% (1 attempt) 100% success |

19% (104 attempts) 84% success |

| O-HSE | 4.6% (25 attempts) 44% success |

8.5% (46 attempts) 70% success |

Note.

Y-HEE = Younger-Higher English Experience; Y-HSE = Younger-Higher Spanish Experience; O-HEE = Older-Higher English Experience; O-HSE = Older-Higher Spanish Experience.

There was a significant relationship between test language and group, χ2 (9) = 72.14, p < .001, for successful and unsuccessful code switching. A follow-up test within each language was conducted. Fishers exact test demonstrated no difference across groups in distribution of successful and unsuccessful code switches from English to Spanish. For Spanish to English code switches comparisons by age and language experience using a Pearson chi-square indicated that children were generally more successful than unsuccessful when code-switching. Further, the Y-HEE group tended to be less successful than expected while the O-HEE group demonstrated more success than expected, χ2 (3) = 10.49, p = .015. The effect size (Cramer’s V) was .213.

Predictors of Semantic Performance

Two forward stepwise regressions were performed to investigate the factors that predicted performance in the two languages. In the first regression, age, percent English use, number of years learning English, and proportion of semantic responses in the Spanish task (with the three trials combined) were entered as predictors and proportion of semantic responses in the English task (three trials combined) was the outcome variable. Age, percent English use, and number of years learning English were selected as predictors because these variables respectively represented general developmental level, current frequency of English use, and cumulative experience with the English language. Proportion of Spanish semantic responses was selected because this would allow us to examine if semantic skills was interdependent across languages. The model was significant, F (3, 56) = 8.86, R2 = 32.2%, p < .001. Percent English use was entered in the first step, accounting for 14.4% of the variance; Spanish semantic performance was entered in the second step, accounting for an additional 8.4% of the variance; and number of years learning English was entered in the third step, accounting for another 9.4% of the variance. Chronological age was not a significant predictor. Higher English use, longer years learning English, and higher Spanish performance contributed to higher English semantic performance.

In the second regression, age, percent Spanish use, number of years learning English, and proportion of semantic responses in the English task were entered as predictors and proportion of semantic responses in the Spanish task was the outcome variable. The model was significant, F (4, 55) = 8.20, R2 = 37.3%, p < .001. Percent Spanish use was entered in the first step, accounting for 11.6% of the variance; chronological age was entered in the second step, accounting for an additional 12.1% of the variance; number of years learning English was entered in the third step, accounting for another 5.9% of the variance; and English semantic performance was entered in the last step, accounting for 7.8% of the variance. Higher Spanish use, older chronological age, shorter years learning English, and higher English performance contributed to higher Spanish semantic performance.

Discussion

Spanish-English bilingual children between 7;3 and 9;11 participated in a repeated association task that tapped depth of semantic knowledge in their two languages. Consistent with the Revised Hierarchical Model (Kroll & Stewart, 1994; Kroll et al., 2002, 2010), depth of semantic knowledge was dependent on developmental level (as indexed by chronological age) and amount of language experience. Unbalanced language experience led to an asymmetry in Spanish and English semantic performance. Subtypes of semantic responses, paradigmatic and syntagmatic, were differentially affected by age and repeated elicitation. We discuss each of these points below.

Developmental Level

Middle childhood is an important period for semantic enrichment as children begin schooling and learn to read (Nelson, 1977; Nippold, 2007). Although the younger and older children were only 18 months apart, two age related differences were observed. First, the older children gave 12% more semantic responses than the younger children. Although significant, the effect size was modest in size (ηp2= .11). This result was consistent with previous studies which indicated moderate gains in semantic elaboration between English-speaking first and fifth graders (Johnson & Anglin, 1995). Carey (1978) found that preschoolers were able to establish a link between a novel word and a referent after hearing the word in an utterance only once. However, after several months of occasional exposures to the novel word, half of the children were still unable to provide an adequate definition to allow for correct identification of the referent. Semantic elaboration is a gradual process and requires many encounters with the target word and can be more prolonged for bilingual children who have reduced exposure to words in each language.

We were also interested in comparing the size of age-related difference between English and Spanish given previous reports of accelerated growth in English vocabulary and lexical processing skills (Cobo-Lewis et al., 2002; Kohnert & Bates, 2002; Kohnert et al., 1999). Contrary to previous results, we did not find an interaction between age and test language. This discrepancy between our study and previous reports may also be attributed to the slow nature of semantic elaboration. Although bilingual children can establish many novel word representations and expand the breadth of their English vocabulary rather quickly, refining and integrating these representations to existing semantic networks is a laborious process for both languages.

The second age-related difference pertains to code switching. While all four groups rarely switched from English to Spanish, the older children were more likely to switch from Spanish to English than the younger children. On average, the older groups switched 14% of the time and the younger groups switched 6% of the time. This increased rate of Spanish to English code switching in the older children may be a precursor of the eventual dominance shift observed in previous studies of Spanish-English bilingual children and adolescents (Kohnert & Bates, 2002; Kohnert et al., 1999). It is also important to note that the older children were highly successful with their code-switching attempts. On average, 75% of their attempts resulted in semantically related responses. In keeping with current views of code switching (Heredia & Altarriba, 2001), our result suggests that the older children were able to deploy their linguistic resources to complete the task when a particular lexical item was unavailable in the target language. The longer-term exposure to both languages in the older children may have afforded them numerous cross-language semantic connections and enabled them to use their knowledge across the two languages.

Language Experience

Our prediction regarding the effect of language experience on semantic depth was supported by the results. In line with the RHM, we found patterns of asymmetry in children’s semantic performance across the two languages. As illustrated in Figure 1, these unbalanced bilinguals produced 18% more semantic responses in their more frequently used than less used language. This effect (ηp2 =.33) was larger than the effect of age, suggesting that experience using a specific language may be a more important determinant in forming semantic connections than general linguistic experience.

Our prediction regarding code switching was partially borne out in the data. Although the two HSE groups switched more often from English to Spanish (a total of 29 attempts) than the two HEE groups (2 attempts), the difference was not statistically significant. By contrast, code switches from Spanish to English were significantly more frequent in the HEE (176 attempts) than the HSE groups (59 attempts). While all the children tended to switch more often from Spanish to English than vice versa, the ones with more experience using English switched to a greater extent. These patterns illustrate the dual influence of social context and language experience on code switching among bilingual children. Furthermore, we found that the O-HEE group had the greatest success with their Spanish to English code-switches, providing semantically relevant information with 84% of these responses. The experience these children had with both languages, a result of their older age and their longer-term exposure to English, may be particularly beneficial to building cross-language semantic connections.

Regression analyses yielded further information regarding the role of language experience on semantic learning. Percent language use and number of years learning English were significant predictors for task performance in both languages. These findings corroborated the important role of language exposure and use in vocabulary acquisition (Bohman, Bedore, Peña, Méndez-Pérez, & Gillam, 2010; Pearson, Fernández, Lewedeg, & Oller, 1997; Sheng, Lu, & Kan, in press).

Chronological age was also a predictor of semantic performance, but only in Spanish. Although age corresponded with cumulative experience learning Spanish, it did not neatly match up with the amount of experience in English for these bilingual children. This finding suggests that when age and language experience conflate, age emerges as a significant contributor to semantic development; but when by itself (or when age and language experience diverge), it is no longer a factor. This finding corroborates our earlier argument that experience using a particular language may be a stronger determinant of semantic development than age, at least for the short age gap sampled in the current study.

The mutually predictive relationship between Spanish and English semantic performance also deserves our attention. This finding is consistent with the linguistic interdependence hypothesis (Cummins, 1979) and substantiates the view that bilingual children are able to use their semantic skills in one language to leverage learning in the other language (Ordóñez, Carlo, Snow, & McLaughlin, 2002).

Paradigmatic and Syntagmatic Relations

Analyses on subtypes of semantic responses offered us insights into the kinds of semantic relations that undergo changes during middle childhood. Regardless of their age, children were equally adept at producing syntagmatic responses; age-related differences were only manifested in paradigmatic responses. These patterns were in alignment with our predictions and suggest that school-age children gain semantic depth by acquiring semantic connections that are categorical, synonymous, or antonymous in nature. In a similar vein, there was a sharp decrement in paradigmatic responses across elicitations; at the same time syntagmatic responses remained constant. The decrease in paradigmatic responses may be a result of shallow vocabulary because children may not have stored many words that belong to the same category or words that are similar in meaning to the targets. Alternatively, this pattern may reflect difficulties in retrieving paradigmatically related words, which is aptly accounted for by the spreading activation model of semantic networks (for more details, see Collins & Loftus, 1975; and Sheng & McGregor, 2010). Without a measure of vocabulary breadth, we are unable to tease apart these two competing explanations. Nevertheless, both semantic storage and semantic retrieval are dimensions of semantic depth. Finally, the effect of language experience was observed in both paradigmatic and syntagmatic responses, suggesting that language experience contributes to the formation and solidification of both kinds semantic relations.

Limitations

The current study is not without limitations. We grouped our participants by age and language experience but the groups differed on age of English onset and by extension, years learning English, and bilingual type. These latter factors are integral to a bilingual’s language experience and should be controlled or experimentally manipulated in future studies. Also, regression analyses indicated that age and the language experience factors accounted for between a quarter to a third of the variance in semantic performance. Clearly there were other factors that were not considered in our study. In particular, vocabulary size (or lexical breadth) is a strong predictor of children’s semantic depth (Vermeer, 2001). Future studies of semantic depth should strive to include a measure of lexical breadth to allow for a more complete examination of semantic development.

Conclusion

Semantic development in bilingual children is a dynamic process. This study was able to reveal the intricate relationships among general development, amount of experience using particular languages, and the development of deep semantic knowledge. With maturity and longer-term use of two languages come denser semantic connections both within each language and across the two languages. With increased experience using a specific language comes deeper semantic knowledge in that language. Both factors were important but the present results suggested that experience using a specific language was a stronger determinant of semantic development than age for bilingual children during middle childhood.

Acknowledgments

This research is funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD Grant R21HD053223). The authors wish to thank the students, teachers, and families for participating in this project.

References

- Bloom P. How children learn the meanings of words. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bohman TM, Bedore LM, Peña ED, Méndez-Pérez A, Gillam RB. What you hear and what you say: Language performance in Spanish English bilinguals. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. 2010;13:325–344. doi: 10.1080/13670050903342019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brysbaert M, Duyck W. Is it time to leave behind the Revised Hierarchical Model of bilingual language processing after fifteen years of service? Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2010;13:359–371. doi: 10.1017/S1366728909990344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brysbaert M, Verreyt N, Duyck W. Models as hypothesis generators and models as roadmaps. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2010;13:383–384. doi: 10.1017/S1366728910000167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carey S, Bartlett E. Acquiring a single new word. Proceedings of the Stanford Child Language Conference. 1978;15:17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Cobo-Lewis AB, Pearson BZ, Eilers RE, Umbel VC. Effects of bilingualism and bilingual education on oral and written English skills: A multifactor study of standardized test outcomes. In: Oller DK, Eilers RE, editors. Language and literacy in bilingual children. Buffalo, NY: Multilingual Matters; 2002. pp. 64–97. [Google Scholar]

- Collins AM, Loftus EF. A spreading activation theory of semantic processing. Psychological Review. 1975;82:407–428. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.82.6.407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cronin VS. The syntagmatic-paradigmatic shift and reading development. Journal of Child Language. 2002;29:189–204. doi: 10.1017/S0305000901004998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins J. Linguistic interdependence and the educational development of bilingual children. Review of Educational Research. 1979;49:222–251. doi: 10.3102/00346543049002222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davies M. Corpus del Español (100 million words, 1200s-1900s) 2002 Available online at http://www.corpusdelespanol.org.

- Davies M. The Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA): 400+ million words, 1990-present. 2008 Available online at http://www.americancorpus.org.

- Entwisle D. Word associations of young children. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins Press; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Gollan TH, Montoya RI, Cera C, Sandoval TC. More use almost always means a smaller frequency effect: Aging, bilingualism, and the weaker links hypothesis. Journal of Memory and Language. 2008;58(3):787–814. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Clellen VF, Kreiter J. Understanding child bilingual acquisition using parent and teacher reports. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2003;24(2):267–288. doi: 10.1017/S0142716403000158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer CS, Lawrence FR, Miccio AW. Exposure to English before and after entry to Head Start: Bilingual children’s receptive language growth in Spanish and English. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. 2008;11:30–56. doi: 10.2167/beb376.0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heredia R, Altarriba J. Bilingual language mixing: Why do bilinguals code-switch? Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2001;10:164–168. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.00140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CJ, Anglin JM. Qualitative developments in the content and form of children’s definitions. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1995;38:612–629. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3803.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohnert K, Bates E. Balancing bilinguals II: Lexical comprehension and cognitive processing in children learning Spanish and English. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research. 2002;45:347–359. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/027). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohnert K, Bates E, Hernandez AE. Balancing bilinguals: Lexical-semantic production and cognitive processing in children learning Spanish and English. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1999;42:1400–1413. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4206.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroll JF, Stewart E. Category interference in translation and picture naming: Evidence for asymmetric connections between bilingual memory representations. Journal of Memory and Language. 1994;33:149–174. doi: 10.1006/jmla.1994.1008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kroll JF, Van Hell JG, Tokowicz N, Green DW. The Revised Hierarchical Model: A critical review and assessment. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2010;13:373–381. doi: 10.1017/S136672891000009X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCardle P, Leung CYY. English language learners: Development and intervention- An introduction. Topics in Language Disorders. 2006;26:302–304. doi: 10.1097/00011363-200610000-00003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson K. The syntagmatic-paradigmatic shift revisited: A review of research and theory. Psychological Bulletin. 1977;84:93–116. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.84.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nippold MA. Later language development: School-age children, adolescents, and young adults. 2. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ordóñez CL, Carlo MS, Snow CE, McLaughlin B. Depth and breadth of vocabulary in two languages: Which vocabulary skills transfer? Journal of Educational Psychology. 2002;94:719–728. doi: 10.1037//0022-0663.94.4.719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson J, Pearson BZ. Bilingual lexical development: Influences, contexts, and processes. In: Goldstein BA, editor. Bilingual language development and disorders in Spanish-English speakers. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes; 2004. pp. 77–104. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson BZ, Fernández SC, Lewedeg V, Oller DK. The relation of input factors to lexical learning by bilingual infants. Applied Psycholinguistics. 1997;18:41–58. doi: 10.1017/S0142716400009863. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peña ED, Gutierrez-Clellen V, Iglesias A, Goldstein BA, Bedore LM. Bilingual English Spanish Assessment (BESA) in development. [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo MA. Identifiers of predominantly Spanish-speaking children with language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, Hearing Research. 1998;41:1398–1411. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4106.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez J, Díaz R, Duran D, Espinosa L. The impact of bilingual preschool education on the language development of Spanish-speaking children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 1995;10:475–490. doi: 10.1016/0885-2006(95)90017-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng L, Lu Y, Kan PF. Lexical development in Mandarin-English bilingual children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 2011;14:579–587. doi: 10.1017/S1366728910000647. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng L, McGregor KK. Lexical-semantic organization in children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2010;53:146–159. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0160). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng L, McGregor KK, Marian V. Lexical-semantic organization in bilingual children: Evidence from a repeated word association task. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2006;49:572–587. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/041). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng L, Peña ED, Bedore LM, Fiestas C. Semantic deficits in Spanish-English bilingual children with language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2012;55:1–15. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2011/10-0254). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeer A. Breadth and depth of vocabulary in relation to L1/L2 acquisition and frequency of input. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2001;22:217–234. doi: 10.1017/S0142716401002041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Winsler A, Díaz R, Espinosa L, Rodríguez J. When learning a second language does not mean losing the first: Bilingual language development in low income Spanish-speaking children attending bilingual preschool. Child Development. 1999;70:349–362. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]