Abstract

Objectives

Examine the effect of current level of smoking and lifetime tobacco consumption on mortality in persons 75–94 years of age.

Methods

Data were from a representative sample of older Jewish persons in Israel, which included 1,200 self-respondent participants aged 75–94 (Mean=83.1, SD=5.3) from the Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Aging Study (CALAS). Data collection took place during 1989–1992. Mortality data on 95.1% of the sample at 20-year follow up were recorded from the Israeli National Population Registry.

Results

The following variables adversely affected mortality for the whole sample: Smoking 11–20 cigarettes daily (HR=1.276, p<.05), smoking over 20 cigarettes daily (HR=1.328, p<.05), total tobacco consumption (HR=1.002, p<.01), and heavy lifetime tobacco consumption (HR=1.270, p<.01). Results were similar for persons aged 75–84, but the effect of smoking seems to decrease or disappear for ages 85 and above.

Conclusion

This is the first report of all-cause mortality risk in both genders of a representative population aged 75 and over. Increased mortality risk is related to high daily quantity of current smoking, and to cumulative amount of lifetime smoking. The effect of smoking may disappear for ages 85 and above, and should be studied in larger oldest-old samples.

Keywords: smoking, older persons, mortality

Introduction

Elevated mortality risks associated with smoking have been reported in middle-aged persons (Jacobs Jr et al., 1999), and in persons of circa 70 years of age (Lam et al., 2007; Yates et al., 2008). Evidence on the relationship between smoking and mortality in persons ages 80 and over is scant and inconclusive. Some reported a relationship between increased mortality and smoking in this age-group (Murakami et al., 2011; Taylor Jr et al., 2002). In contrast, others reported no association between smoking and increased mortality in men ages 85–90, and a decreased mortality risk in men ages 90 and above, compared to non-smokers, suggesting the emergence of a survival effect as age increases (Lam et al., 2007). A recent meta-analysis of 17 cohort studies of persons ages 60 and above found that current smokers demonstrate a circa twofold risk of all-cause mortality when compared to never smokers. Age-analysis revealed that the lowest, yet still statistically significant, relative mortality risk was found in the oldest sub-group, i.e., current smokers over 80 years of age, yet for that age group, only 4 studies were found (Gellert et al., 2012).

We aim to examine the effect of smoking on mortality in Israeli persons aged 75–94. The increased numbers of older persons in this age bracket worldwide underscore the need for understanding the effect of smoking on mortality in this age group and its practical implications. We aim to answer the following questions: Is smoking associated with increased mortality even in persons aged 75–94, who survived as smokers? How do different indicators pertaining to current and past smoking (i.e., lifetime tobacco consumption, and current level of smoking) impact mortality in persons who survived to age 75? What is the difference in the relationship between smoking and mortality between old persons (aged 75–84) and old-old persons (aged 85–94)?

Methods

Participants and Procedure

The sample was part of the Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Aging Study (CALAS). The CALAS conducted a multidimensional assessment of a random sample of the older Jewish population in Israel, stratified by age group (75–79, 80–84, 85–89, 90–94), gender, and place of birth (Asia-Africa, Europe-America, Israel). Data collection took place during 1989–1992. The inclusion criteria were being self-respondent, living in a community dwelling, and aged between 75–94 years resulting in a sample of 1,200. The CALAS was approved for ethical treatment of human participants by the Institutional Review Board of the Chaim Sheba Medical Center in Israel.

Measures

Socio-demographics include age, gender, place of birth (Israel, Middle East/North Africa, Europe/America), marital status (unmarried, married), number of children (alive and deceased), education (number of years), and financial situation (having additional income beyond social security).

Smoking

This section was based on the EPESE questionnaire (Cornoni-Huntley et al., 1980) and includes current smoking status (non-smoker, past smoker, current smoker), age of smoking initiation, age of smoking cessation, and daily quantity of cigarettes (none, 1–10, 11–20, over 20). This categorization was used because of the smoking prevalence distribution (see table 1; only 35 participants smoked over 40 cigarettes per day). Total tobacco consumption was calculated by multiplying the number of daily cigarettes by the number of years of smoking. This variable was then categorized into three levels: never smoked, non-heavy lifetime smoker (up to 60 in life consumption),), and heavy lifetime smoker. Total number of years of smoking was calculated by subtracting the age of smoking initiation from the participant's current age (or the age of smoking cessation in cases of past smoking).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (Israel, 1989–1992).

| Full sample | Ages 75–84 | Ages 85–94 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=1200 | n=752 (54 alive) | n=448 (5 alive) | |

|

|

|||

| M(SD) / % | |||

| Age | 83.1(5.3) | 79.63(2.83) | 88.93(252) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 44.9 | 47.2 | 41.1 |

| Place of birth | |||

| Europe | 37.0 | 37.0 | 36.6 |

| East | 32.7 | 31.6 | 34.4 |

| Israel | 30.3 | 31.1 | 29.0 |

| Married | |||

| Single | 53.2 | 47.1 | 64.0 |

| Education (years) | 7.63(5.57) | 7.67(5.32) | 7.56(5.84) |

| Income | |||

| No additional income | 41.8 | 39.1 | 46.3 |

| Smoking | |||

| Noa | 56.2 | 54.7 | 58.7 |

| In the past | 33.0 | 34.0 | 31.2 |

| Yes | 10.9 | 11.3 | 10.1 |

| Total tobacco consumption | 30.22(49.04) (range: 0–231) |

31.42(45.70) (range: 0–207) |

28.14(50.52) (range: 0–231) |

| Daily quantity of smoking | |||

| Nonea | 59.2 | 52.4 | 62.4 |

| 1–10 | 17.8 | 17.8 | 17.7 |

| 11–20 | 12.90 | 14.6 | 9.9 |

| more than 20 | 10.10 | 10.3 | 9.9 |

| Years of smoking | 17.14(24.05) (range: 0–79) |

17.59(23.59) (range: 0–73) |

16.36(24.55) (range: 0–79) |

| Age of smoking cessation for past smokers | 59.41(15.63) (range: 14–94) (median=61) |

58.31(14.62) (range: 14–86) (median=60) |

61.41(77.23) (range: 20–94) (median=65) |

| Years of smoking cessation for past smokers | 23.59(15.62) (range=0–72) (median=20) |

21.42(14.39) (median=0–68) (median=20) |

27.52(17.03) (range=0–72) (median=24) |

Pairwise deletion was applied for missing cases. Variations in estimates are due to missing data in some variables.

Mortality Follow-Up

Mortality data within 20 years from the date of sampling were recorded from the National Population Registry (NPR). Of the original sample, 59 participants were still alive. Hence, we had complete mortality data on 95.1% of the sample.

Statistical Analysis

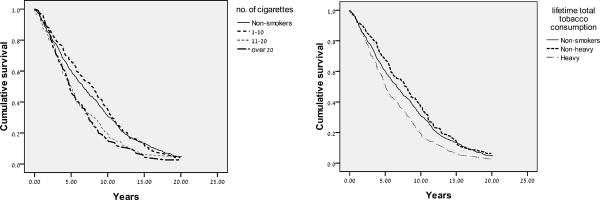

Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank testing were used to examine the influence of smoking on mortality, based on 1) current level of smoking (none, 1–10, 11–20, and over 20 cigarettes), and 2) smoking status as non-smoker, non-heavy lifetime consumption, and heavy consumption.

Cox proportional-hazards models were undertaken to adjust for established mortality risk factors and to calculate hazard ratios with 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) for mortality. Six approaches were taken to parameterize smoking-related variables. Each parameterization of smoking was used in a separate model. The parameterizations were: 1) daily quantity of smoking: 0 (non smokers), 1–10 cigarettes, 11–20, over 20, 2) total tobacco consumption, 3) categorized tobacco consumption (0, non-heavy and heavy), 4) total years of smoking, and 5) smoking status (current smoker, past smoker, never smoker, as well as smoking status designated as ever smokers vs. never smokers).

Four analyses were done for each parameter. First, the effect of the variable without adjustment for confounders was run (A). Second, we adjusted for age and sex (B). Third, we adjusted for age, sex, place of birth, marital status, education, and income (C). Finally, we adjusted for age, gender (vs. female), place of birth (Europe vs. Israel, East vs. Israel), marital status (vs. single), income (vs. no additional income), education, number of children, health (subjective health and number of medications), and ADL (D). We then examined the effects of the smoking variables separately for those aged 75–84 and 85–94 using the fully adjusted model (D).

Finally, in order to examine the impact of years of smoking cessation on mortality, a separate analysis was conducted for past smokers examining the impact of years of smoking cessation on mortality for the full sample as well as separately for those aged 75–84 and 85–94 using the fully adjusted model.

Results

Participants' characteristics are presented in Table 1. Only 10.9% of the sample were current smokers, and nearly 33% were past smokers. The relationship between current levels of smoking and mortality is presented in Figure 1a. Current levels of smoking are significantly associated with mortality (Log Rank Mantel-Cox: χ2(3)= 18.377, p<.001).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves according to current number of cigarette smoked (1a) and to no smoking, non-heavy, and heavy smoking (1b) in persons aged 75–94 (based on 20-year follow-up mortality data in an Israeli sample; data collection took place during 1989–1992).

The survival curves for current smokers of 11–20 and over 20 cigarettes both show worse survival than is seen for non-smokers and light smokers (1–10). The group with the best survival over the first 12 years seems, paradoxically, to be the light smokers, rather than the non-smokers. The fully adjusted Cox model (Table 2) indicates lack of statistical significance between the nonsmokers and the light smokers in survival (p>.05).

Table 2.

Predicting mortality (at 30.6.2009) in 20 years from date of (first) interview by various measures of smoking status (older persons in CALAS. Ages 75–94, self reporting living in the community, N=1200; 59 are still alive; Israel, 1989–1992).

| Hazard Ratio (CI) for mortality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| A. Unadjusted | B. Age- and sex-Adjusted | C. Multivariable-Adjusteda | D. Multivariable-Adjustedb | |

| 1. Daily quantity | *** | *** | ** | * |

| 1–10 (vs. no) | .953 (.812–1.119) | .947 (.801–1.116) | .972 (.819–1.153) | 1.013 (.852–1.206) |

| 11–20 (vs. no) | 1.277** (1.063–1.535) | 1.359** (1.120–1.640) | 1.288* (1.054–1.576) | 1.276* (1.041–1.564) |

| over 20 (vs. no) | 1.410** (1.153–1.723) | 1.300* (1.052–1.608) | 1.303* (1.046–1.622) | 1.328* (1.063–1.659) |

| 2. Total tobacco consumption | 1.002*** (1.001–1.004) | 1.002** (1.001–1.003) | 1.002** (1.001–1.003) | 1.002** (1.001–1.004) |

| 3. Level of total tobacco consumption | *** | * | ** | * |

| Non-heavy (<60) (vs.0) | .889 (.749–1.055) | .935 (.785–1.113) | .922 (.711–1.104) | .957 (.799–1.148) |

| Heavy (60+) (vs. 0) | 1.309** (1.124–1.525) | 1.243* (1.054–1.468) | 1.254* (1.054–1.491) | 1.270** (1.065–1.515) |

| 4. Years of smoking | 1.003* (1.000–1.005) | 1.002 (1.000–1.005) | 1.003 (1.000–1.006) | 1.003 (1.000–1.006) |

| 5. Smoking status | * | * | ||

| Past smoker (vs. never-smoker) | 1.172* (1.032–1.331) | 1.171* (1.022–1.342) | 1.135 (.986–1.307) | 1.155* (1.001–1.334) |

| Current smoker (vs. never-smoker) | .978 (.805–1.108) | .934 (.766–1.139) | .990 (.803–1.221) | .987 (.797–1.222) |

| Current smoker (vs. past smoker) | .839 (.684–1.030) | .806 (.655–.990) | .886 (.713–1.102) | .880 (.702–1.104) |

Adjusted for age, gender (vs. female), place of birth (Europe vs. Israel, East vs. Israel), marital status (vs. single), income (vs. no additional income), education.

Adjusted for age, gender (vs. female), place of birth (Europe vs. Israel, East vs. Israel), marital status (vs. single), income (vs. no additional income), education, having children, health (subjective health and #medications) and ADL

Hazard Ratio= Exp(b); CI= Confidence Interval;

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001

Survival curves for total lifetime consumption are shown in Figure 1b. Total lifetime tobacco consumption was significantly associated with mortality (Log Rank Mantel-Cox: χ2(2)= 16.953, p<.001). Heavy levels of lifetime tobacco consumption were associated with the lowest levels of survival, whereas the non-heavy levels were associated with survival similar to non-smoking (Figure 1b). Non-heavy smoking appeared to have a somewhat better survival than non-smoking. However, the advantage was not statistically significant (Table 2).

The following smoking variables added significantly to mortality risk in the adjusted multivariate analyses: Smoking 11–20 cigarettes daily (Hazard Ratio (HR)=1.276, CI: [1.041–1.564], p=.019); smoking over 20 cigarettes daily (HR=1.328, CI: [1.063–1.659], p=.013); total tobacco consumption (HR=1.002, CI: [1.001–1.004] , p=.002); and heavy lifetime tobacco consumption (HR=1.270, CI: [1.065–1.515] , p=.008). The effect of years of smoking was borderline (HR=1.003, CI: [1.000–1.006], p =.065).

The results for the 75–84 age group reflected the results for the full sample, i.e., the variables that predicted mortality were high daily quantity of smoking (over 10 cigarettes), total lifetime tobacco consumption, and heavy (but not non-heavy) total tobacco consumption. Also, similar to findings for the whole population, there was a trend (p<.1) for an effect of years of smoking. Although none of the variables in the 85–94 age group significantly predicted mortality (Table 3), indicators of lifelong smoking had HRs larger than 1, indicating potential increased mortality associated with lifelong smoking. In contrast, indicators of current light smoking (less than 10 cigarettes, non-heavy level of consumption, and being a current smoker) all had HRs smaller than 1, suggesting no negative impact of smoking. The lack of statistical significance seems to be a function of smaller effect sizes (Table 3), as even when combining the two subgroups of 11–10 and 20+ cigarettes, the results were not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Comparison of ages 75–84 to ages 85–94 on the predictive value of various measures of smoking for mortality during 20 years following the date of first interview (Israel, 1989–1992), after controlling for demographic and health variables.

| Ages 75–84 n=752 (54 alive) | Ages 85–94 n=448 (5 alive) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Hazard Ratio (CI) | ||

|

|

||

| 1. Daily quantity | * | |

| 1–10 (vs. no) | 1.037 (.831–1.295) | .925 (.691–1.239) |

| 11–20 (vs. no) | 1.295* (1.013–1.657) | 1.178a (.810–1.712) |

| over 20 (vs. no) | 1.439* (1.083–1.913) | 1.116 (.773–1.610) |

| 2. Total tobacco consumption | 1.002** (1.001–1.004) | 1.001 (.999–1.004) |

| 3. Level of total tobacco consumption | d | |

| Non-heavy (<60) (vs.0) | 1.019 (.814–1.275) | .820 (.596–1.128) |

| Heavy (60+) (vs. 0) | 1.306* (1.041–1.637) | 1.143 (.853–1.530) |

| 4. Years of smoking | 1.004 (1.000–1.007)d | 1.001 (.996–1.006) |

| 6. Smoking status | ||

| Past smoker (vs. never-smoker) | 1.186 (.987–1.424)d | 1.052 (.8291.334) |

| Current smoker (vs. never-smoker) | 1.028 (.784–1.347) | .932 (.642–1.353) |

| Current smoker (vs. past smoker) | .900 (.673–1.205) | .977 (.644–1.484) |

| Ever smoker (vs. never-smoker) | 1.170 (.987–1.387)d | 1.025 (.820–1.281) |

Adjusted for age, gender (vs. female), place of birth (Europe vs. Israel, East vs. Israel), marital status (vs. single), income (vs. no additional income), education, having children, health (subjective health and #medications) and ADL.

Hazard Ratio= Exp(b); CI= Confidence Interval;

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

.l > p > .05.

Because of the small groups sizes of those smoking 11–20 and 20+ cigarettes in the 85+ group, we conducted an additional regression combining those groups, yet the combined effect was also not statistically significant.

The results concerning the impact of years of smoking cessation on mortality are presented in Table 4. A larger number of years of smoking cessation was associated with reduced mortality in past smokers for all age subgroups, though the effect for the higher age group was marginal.

Table 4.

The impact of years of smoking cessation on mortality in past smokers for the full sample (n=329) and by age group (Israel, 1989–1992).

| Full sample | 75–84 | 85–94 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n= 329 | n= 210 | n= 119 | |

| χ 2 (1) | 14.059*** | 10.922** | 4.224* |

| Hazard Ratio (CI) | |||

| Years of smoking | .986(.979–.993)*** | .983(.972–.993)** | .987(.975–1.000)* |

| cessation |

Adjusted for age, gender (vs. female), place of birth (Europe vs. Israel, East vs. Israel), marital status (vs. single), income (vs. no additional income), education, having children, health (subjective health and #medications) and ADL.

Hazard Ratio= Exp(b); CI= Confidence Interval;

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001

Discussion

We investigated the relationship between smoking and mortality in a random sample of older Israelis, with all participants having survived at least 75 years of age at baseline. The parameters of smoking associated with mortality in this population were: 1) cumulative amount of smoking, based on both daily levels and number of years of smoking, and 2) daily quantity of current smoking. The effect of 11–20 daily cigarettes and over 20 cigarettes were similar, with a significant increase in mortality. In contrast, those who smoked 1–10 cigarettes were not at increased mortality risk. In the fully adjusted model, the highest mortality was associated with the highest levels of smoking.

Total tobacco consumption was previously found to adversely affect older persons' mortality risk (via the construct of pack-years; see Gellert 2012). Since we found a significant effect for lifetime tobacco consumption on mortality, evidence from the current study suggests that the hazards of total tobacco consumption in later life extend well into old-old age.

Our findings corroborate previous research (Doll et al., 2004; Fujisawa et al., 2008), generally associating increased mortality risk with higher daily smoking levels (Gellert et al., 2012). Investigating the role of current smoking levels, the cutoff point for increased mortality was 10 cigarettes. This, in contrast to a cutoff of 5 found in a 25-year mortality follow-up of men aged 65–84 (Jacobs Jr et al., 1999), and of 20 found in a 4-year follow-up of Japanese persons aged 80 at baseline (Fujisawa et al., 2008).

In line with previous research (Gellert et al., 2012), past smokers had a significantly higher mortality than never-smokers. In our study the mean age of smoking cessation is about 60. Paganini-Hill and Hsu (1994) have illustrated the drawbacks of late smoking cessation as mortality was increased in former smokers who quit at age 65 or older when compared to those who quit earlier. Conversely, Jacobs Jr et al. (1999) demonstrated the benefits of long term smoking cessation (sample ages 40–59) as risk of death after 10 years or more of smoking cessation was reduced to almost the same risk level to never smokers. Our results differ, since despite over 20 years of smoking cessation on average, past smokers had a significantly higher mortality than that of never smokers.

We did not find a significant difference on mortality between past and current smokers. Our findings differ from evidence of increased mortality in current smokers compared to past smokers (Murakami et al., 2011), possibly due to the small sample size of current smokers, the late age of smoking cessation, the older age of the cohort under study, or the fact that most of the current smokers smoked less than 10 cigarettes a day, a rate that was not associated with increased mortality in the current study. Past smokers who had a larger number of years of smoking cessation showed a lower mortality risk (Table 4). It may also be that lifetime usage of tobacco is the chief determinant of mortality among past smokers in those aged 75 and over. Our measurement of tobacco consumption is limited because it was based on a single report of smoking frequency, which may have changed over time.

When comparing the effect of current light smoking in persons aged 85–94 to those aged 75–84, a shift in direction was noted. While indicators of lifelong smoking attest toward increased mortality in all age groups, light smoking has a non-significant risk ratio lower than 1 in the 85–94 age group, but higher in the younger group, when compared to non-smokers. Previous evidence suggests that although the mortality risk associated with current smoking decreases as age progresses, current smoking engenders higher mortality even in highest ages (Gellert, 2012). Our findings differ, observing that this pattern may be restricted to non-light smokers. Light smokers ages 85–94 had a mortality hazard ratio lower than 1 in comparison to never smokers, indicating resilience to mortality from low levels of smoking. While this shift in direction is non-significant, despite the increasing frailty in old age among smokers (Hubbard et al., 2009), and the reported associations between light smoking and various diseases (Schane et al., 2010), the present findings support the notion that for those over 84 years of age, the factors affecting mortality are different than those affecting younger populations, and may not include light levels of smoking. This may be due to: 1) a survival effect, which suggests that old-old persons' survival reflects immunity to or protection from the potential risks such as obesity (Cohen-Mansfield & Perach, 2011) or smoking (Lam et al., 2007) that pose threat to younger persons. Indeed, in old-old age, persons become resilient to common stressors (Walter-Ginzburg et al., 2005). A related notion suggests that stabilizing factors (e.g., high self esteem), which have resulted in survival until older age, continue to counterbalance smoking related risks (Brandtstädter & Greve, 1994); 2) the increase in overall mortality in persons above age 70 regardless of their smoking status may reduce the potency of relative-effect attributed to smoking (Gellert et al., 2012); and 3) the notion that excess risk of smoking may not be apparent in this age group because of stronger, competing risks (e.g. cardiovascular disease; (Lam et al., 2007), which tend to overwhelm the clinical picture and obscure the impact of lower level risk factors such as light smoking.

A strength of this study is the 20-year timeline providing an almost complete follow-up. The use of various smoking indicators enabled insight into important considerations such as smoking quantity, frequency, and history. A limitation of the study is the reliance on self-report measures which may lack accuracy. A selection effect is noteworthy, as the sample consisted only of those who survived until old age and could thus enter the study. Also, the number of persons in the 85–94 age group is relatively small. Finally, findings are of a random representative Israeli sample and may not generalize to other populations due to cultural and ethnic differences.

Conclusion

This paper contributes to past literature by elucidating the ambiguous previous findings concerning the effect of smoking in persons 75–94 years of age. It provides several important findings: heavy smoking of over 10 cigarettes a day affects mortality at these ages, but lower levels do not. The lifetime smoking consumption affects mortality even for persons who have survived to the age of 75. The most commonly-used measures in this type of research, including ever smoking vs. never smoking, or past, current vs. never smoking, appear insufficiently sensitive to the effect of smoking on mortality in this age group. Finally, the effect of smoking based on all indicators may decrease or disappear for ages 85 and above, and should be explored in studies of larger oldest-old samples.

Highlights

Smoking over 10 cigarettes, but not less, per day affects mortality at ages 75–94

Lifetime smoking consumption affects mortality in persons who survived to age 75

Past smokers had higher mortality than never smokers, despite a lengthy cessation

The hazardous effect of smoking on mortality may disappear for ages 85 and above

Acknowledgements

Funding The Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Aging Study (CALAS) was supported by the U.S. National Institute on Aging (grants R01-AG05885-03 and R01-5885-06). Parts of the present study were supported by Pinhas Sapir Center for Development and the Israel National Institute for Health Policy (grant R/2/2004).

The above mentioned sources of funding had no role in study design and the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and the writing of the article and the decision to submit it for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest Statement The author has no actual or potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Brandtstädter J, Greve W. The aging self: Stabilizing and protective processes. Dev. Rev. 1994;14:52–80. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Perach R. Is there a reversal in the effect of obesity on mortality in old age? J. Aging. Res. 2011 doi: 10.4061/2011/765071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornoni-Huntley J, Brock DB, Ostfeld AM, Taylor JO, Wallace RB. Established populations for epidemiological studies of the elderly: Resource data book (NIH Publication No. 86-2443) U.S. Public Health Service; Washington, DC: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observations on male British doctors. BMJ. 2004;328:1519–1533. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa K, Takata Y, Matsumoto T, Esaki M, Ansai T, Iida M. Impact of smoking on mortality in 80-year-old Japanese from the general population. Gerontology. 2008;54:210–216. doi: 10.1159/000138336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellert C, Schöttker B, Brenner H. Smoking and all-cause mortality in older people. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012;172:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard R, Searle S, Mitnitski A, Rockwood K. Effect of smoking on the accumulation of deficits, frailty and survival in older adults: A secondary analysis from the Canadian study of health and aging. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 2009;13:468–472. doi: 10.1007/s12603-009-0085-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs DR, Jr, Adachi H, Mulder I, Kromhout D, Menotti A, Nissinen A, Blackburn H. Cigarette smoking and mortality risk: Twenty-five-year follow-up of the seven countries study. Arch. Intern. Med. 1999;159:733–740. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.7.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam TH, Schooling CM, Li ZB, Ho SY, Chan WM, Ho KS, Tham MK, Cowling BJ, Leung GM. Smoking and mortality in the oldest-old, evidence from a prospective cohort of 56,000 Hong Kong Chinese. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2007;55:2090–2091. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami Y, Miura K, Okamura T, Ueshima H. Population attributable numbers and fractions of deaths due to smoking: A pooled analysis of 180,000 Japanese. Prev. Med. 2011;52:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paganini-Hill A, Hsu G. Smoking and mortality among residents of a California retirement community. Am. J. Public Health. 1994;84:992–995. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.6.992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schane RE, Ling PM, Glantz SA. Health effects of light and intermittent smoking. Circulation. 2010;121:1518–1522. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.904235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DH, Jr, Hasselblad V, Henley J, Thun MJ, Sloan FA. Benefits of smoking cessation for longevity. Am. J. Public Health. 2002;92:990–996. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.6.990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter-Ginzburg A, Shmotkin D, Blumstein T, Shorek A. A gender-based dynamic multidimensional longitudinal analysis of resilience and mortality in the old-old in Israel: The cross-sectional and longitudinal aging study (calas) Soc. Sci. Med. 2005;60:1705–1715. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates LB, Djouss L, Kurth T, Buring JE, Gaziano JM. Exceptional longevity in men - Modifiable factors associated with survival and function to age 90 years. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008;168:284–290. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]