Abstract

As much as 73% of persons living with HIV (PLWH) experience sleep disturbances. It has been more than 10 years since the last study that objectively measured sleep behaviors in persons with HIV. The purpose of this pilot study was to explore sleep quality and rest-activity patterns in PLWH. Eight participants completed a sleep diary and 24-hour actigraphy for 1 week. Compared to accepted norms for “good sleepers,” sleep diaries showed moderate sleep disturbance, and actigraphy showed severe sleep disturbance. Bedtime was variable from day-to-day. Analysis of 24-hour rest-activity patterns from actigraphy also showed disorganization of sleep timing across days. Results of this pilot study suggest that sleep disturbance remains problematic in PLWH despite advancements in the disease management. Pharmacological interventions are effective but generally recommended for short-term use. Behavioral treatments may be useful for longer-term management of sleep patterns in PLWH, but further research is needed.

Keywords: HIV, rest-activity patterns, sleep disturbance

Sleep disturbance is a significant problem in persons living with HIV (PLWH), experienced by as much as 73% of this population (Cruess et al., 2003; Rubinstein & Selwyn, 1998). Subjective measures of sleep (questionnaires, sleep diaries) show disruption of sleep continuity including difficulty falling asleep, awakenings during the night, and reduced sleep time (Cohen, Ferrans, Vizgirda, Kunkle, & Cloninger, 1996; Rubinstein & Selwyn, 1998). Objective measures (polysomnography and actigraphy) also show disruption of sleep onset and continuity (Lee, Portillo, & Miramontes, 2001) as well as disruption of sleep stages. Several studies have reported increased slow wave sleep (Reid & Dwyer, 2005), which is considered deep, restorative sleep, but the implications of these findings on perceived sleep quality are unclear. Quality of life and health outcomes in PLWH may be impacted by sleep disturbance (Phillips, Sowell, Boyd, Dudgeon, & Hand, 2005). General consequences of insomnia, including fatigue and mood disturbance, may be compounded by HIV disease and related co-morbidities (Salahuddin, Barroso, Leserman, Harmon, & Pence, 2009). HIV-related sleep disturbance is associated with pain and immune dysfunction (Aouizerat et al., 2010; Cruess et al., 2003). Sleep disturbance may also contribute to poor medication adherence in PLWH (Phillips, Moneyham, et al., 2005), especially if sleep disruption is a side effect of the medication. This problem is particularly concerning given that patients should strive for 100% adherence to medications for effective viral suppression and, therefore, survival (Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents, 2012).

Sleep disturbances in HIV are related to a variety of psychological, physiological, and behavioral factors. Psychological factors known to contribute to insomnia are prevalent in PLWH, including depression, anxiety, and stress related to living with a chronic illness (Cruess et al., 2003; Nokes & Kendrew, 2001; Robbins, Phillips, Dudgeon, & Hand, 2004; Rubinstein & Selwyn, 1998; Salahuddin et al., 2009). Physiological factors related to HIV treatments may contribute to sleep disruption. A limited amount of research has examined the contribution of combined antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimens to insomnia. Most of these studies were done 10 years ago or longer, when typical treatment regimens differed from the present. Some cross-sectional studies and clinical drug studies reported associations between ART and greater rates of self-reported sleep disturbance (Fumaz et al., 2002; Nokes & Kendrew, 2001), whereas other descriptive studies showed no sleep differences based on use of ART (Reid & Dwyer, 2005; Rubinstein & Selwyn, 1998). The specific drugs or drug combinations causing general sleep disturbance are not entirely clear (Reid & Dwyer, 2005). The non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, efavirenz, has been commonly associated with vivid dreams (Moyle, Fletcher, Brown, Mandalia, & Gazzard, 2006). ART regimens are also known to cause lipodystrophy, thereby increasing neck circumference and central obesity leading to obstructive sleep apnea (Reid & Dwyer, 2005; Rubinstein & Selwyn, 1998).

Relative to physiological and psychological factors contributing to sleep disturbance in PLWH, less is known about behavioral factors contributing to sleep disturbance in this population. Maladaptive behaviors are important in the etiology and treatment of insomnia, whether or not insomnia is primary (i.e., not attributable to psychological or physical illness) or precipitated by a chronic disease process (Stepanski & Rybarczyk, 2006). Behaviorally, persons with insomnia tend to prolong their sleep periods; that is, they spend lengthy amounts of time in bed. Much of that time in bed is spent awake, which can further impair the ability to sleep by causing a classically conditioned association of the sleep setting (i.e., bedroom) with wakefulness rather than sleep (Edinger & Means, 2005). Persons with sleep disruption, especially related to psychological or physical illness, may spend large amounts of the daytime sedentary or napping (Lee et al., 2001), further contributing to nighttime sleep disruption.

Common treatments for sleep disturbances include pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches. Prescription sedative medications, such as zolpidem and eszopiclone, have been shown to be effective for improving sleep; however, sedative drugs may be expensive and have side effects such as “hangover” sedation in the morning (Zammit, 2009). Such drawbacks may be of concern to PLWH who are already managing complex medication regimens and related side effects. Sedatives can also prove habit forming (Zammit, 2009), which is also of concern given an elevated risk of substance abuse among PLWH (Volkow & Montaner, 2011). Current practice guidelines for insomnia recommend short-term use of hypnotics and support use of cognitive and behavioral strategies whenever possible (Schutte-Rodin, Broch, Buysse, Dorsey, & Sateia, 2008). Cognitive-behavioral treatments for insomnia aim to correct maladaptive behaviors and cognitions. These treatments have been shown to be highly effective in numerous studies of primary insomnia (Morin et al., 2006) and in studies of persons with insomnia co-morbid with various physical conditions such as arthritis, coronary disease, or chronic pain (Stepanski & Rybarczyk, 2006).

It has been more than 10 years since the last study that objectively measured sleep behaviors in persons with HIV (Lee et al., 2001). That study used actigraphy and showed reduced total sleep time, reduced sleep efficiency, frequent awakenings, and disorganization of rest-activity patterns in women with HIV. In the time since that study, ART regimens have much improved and many more patients can be virally suppressed for extended periods of times. One expectation would be that the previously documented sleep disturbances may have significantly improved; however, the subjective evidence of sleep disturbance suggests that little has improved in the treatment of sleep disturbance in PLWH (Cruess et al., 2003; Nokes & Kendrew, 2001; Salahuddin et al., 2009). Behavioral treatments may be a much-needed addition to treatment of PLWH, but current evidence is lacking on whether or not this population exhibits common insomnia behaviors such as extended time in bed, variable bedtime, and lying in bed for long periods at night while awake.

The purpose of this pilot study was to examine pre-intervention data available from 1 week of sleep diaries and 24-hour wrist actigraphy to explore sleep quality and rest-activity patterns in PLWH. The study’s objective was to clarify areas for further research, including potential treatment targets for behavioral therapies to improve sleep in this population. The specific aims were to (a) describe overall sleep outcomes from subjective (sleep diary) and objective (actigraphy) data in a sample of PLWH, (b) examine sleep timing across 7 days by analyzing the variance of bedtime and time of arising, and (c) examine 24-hour rest-activity patterns.

Methods

Design

These analyses were conducted to describe baseline sleep patterns based on daily sleep diary and wrist actigraphy data collected over 1 week from participants enrolled in a pilot intervention study. The parent study was a one-group pilot study to examine the feasibility and acceptability of an 8-week mind-body intervention for PLWH. This study took place between October 2010 and February 2011 and was approved by the University of Washington Human Subjects Institutional Review Board.

Study Sample and Data Collection

Participants were low income individuals enrolled in a day program for HIV medication management in a day health center in the Pacific Northwest. Social workers identified patients who frequented the outpatient program. These patients were contacted by phone for recruitment by the research coordinator and subsequently screened on the following criteria for participation. Inclusion criteria for the study included HIV-infected persons, outpatient program participants, patients at a local hospital HIV clinic, and persons willing to sign permission for collection of medical data from their charts, willing to sign release to contact the social work staff in the case of concern regarding participant safety or well-being, able to read and write in English, available for the intervention on days when mind-body intervention sessions were offered, and willing to forgo non-study-related body therapy and mindfulness meditation during the 2-month intervention period. Exclusion criteria were patients diagnosed with psychosis, those with cognitive impairment indicated by chart diagnosis or observable cognitive difficulties, and individuals who reported being in a current abusive domestic/interpersonal relationship.

Nine participants enrolled in the study and were administered baseline questionnaires. During the week prior to the intervention, all enrolled study participants received a one-page sleep diary on which to report their sleep for 1 week. Participants wore an actigraph on their non-dominant wrist during the same week in which they completed the sleep diaries. The procedure for completing the sleep diary was reviewed, and a written and verbal explanation of actigraph care and purpose was provided. The participants were instructed to press the event marker button on the actigraph when they went to bed and when they arose. We collected basic information about sleep environment and primary sleep disorders (sleep apnea and restless legs syndrome) to inform our understanding of possible sleep challenges for each individual.

Measures

Baseline measures

Baseline measures were used to describe participant characteristics. These included a demographic and health history form to describe age, education, socio-economic status, and racial/ethnic identity as well as clinical data retrieved from the medical chart to describe current medications and immune function (viral load).

Sleep diaries

Participants completed standard daily sleep diaries for 1 week. This diary was adapted from a commonly used clinical form (Morin & Espie, 2004). Participants reported bedtime, time of final awakening, time of arising, sleep onset latency (amount of time between going to bed and falling asleep), wake after sleep onset (WASO), and sleep quality (rated 1 to 5). Total sleep time and sleep efficiency were calculated by the investigator from the participant-reported times as follows. Total sleep time equaled time in bed minus sleep onset latency, WASO, and time between awakening and arising. Sleep efficiency (percentage of time in bed spent asleep) equaled total sleep time divided by time in bed (multiplied by 100 to convert to percentage). Sleep efficiency provides a general index of sleep quality, with efficiency of 85-90% or higher representing normal sleep (Edinger et al., 2004).

Wrist actigraphy

Objective sleep outcomes were measured with Actiwatch 2 actigraphs (Mini-mitter Company, Inc., Bend, OR). Participants wore the actigraphs during the same week that they completed the sleep diaries. The Actiwatch 2 is a piezo-electric accelerometer (device that measures movement) about the size of a watch that is worn on the non-dominant wrist. Actiwatch activity counts represent both the occurrence and magnitude of arm movements. The Actiwatches were set to record activity counts in 1-minute epochs. Data were analyzed using Actiware version 5.57 (Mini-mitter Company, Inc., Bend, OR). Bedtime and rise time were entered in the software by a sleep researcher with extensive experience with actigraphy (DT) based on participants’ sleep diary entries and visual inspection of the graphed activity. Each 1-minute epoch was scored as sleep or wake using the automatic algorithm in the software. Because the reliability of sleep onset latency is not well established for actigraphy, we did not report this outcome. The sleep outcomes from actigraphy included total wake time (time in bed spent awake), total sleep time, and sleep efficiency (total sleep time/time in bed *100).

Data Analysis

All statistical data analyses were done using SPSS 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Sleep diary data were double entered in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA) and checked for accuracy before being exported to SPSS for analysis. Sleep outcomes from the actigraphy data were scored in Actiware 5.57, and then the data were exported into text files and imported into SPSS for analysis. Means, standard deviations, and ranges were calculated on outcomes from the sleep diary, actigraphy, bedtime/rise time, root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD), and 24-hour rest-activity analyses.

To examine variability in sleep timing, we calculated the RMSSD of bedtime and rise time. Calculation of RMSSD is similar to standard deviation, except that RMSSD accounts for the time sequencing of the data. That is, RMSSD is calculated from the difference between successive days (bedtime day 1 – bedtime day 2, bedtime day 2 – bedtime day 3, and so forth) whereas standard deviation compares each bedtime to the mean of all bedtimes without accounting for the data sequence. RMSSD provides information on the extent of variability in bedtime and rise time between adjacent days.

Non-parametric circadian rhythm analysis was conducted according to the methods described by Van Someren (2007). This method provides information on the stability and variability of rest and active periods. For a person with varying sleep timing and poor sleep across days, circadian rhythm analysis would reflect low interdaily stability (range is 0-1, closer to 0 represents less stability). For a person with disorganized rest and activity patterns within each day, circadian rhythm analysis would show high intradaily variability (range is usually 0-2, higher values reflect more variability); high variability could be caused by alternations between rest and activity during the daytime, nighttime, or both. Finally, circadian rhythm analysis provides information on how active an individual is during daytime versus nighttime, which is shown in the relative amplitude (range is 0-1). High amplitude (values closer to 1) reflects more robust activity during time awake versus time at rest/asleep. Amplitude may be reduced by high activity during the rest period (e.g., restless sleep) or by low activity during daytime.

To prepare for the non-parametric circadian rhythm analysis, data quality was examined in Actiware 5.57 and missing or off-wrist periods were marked. Raw actigraph activity data were exported to text files and imported into SPSS for analysis. Missing data were imputed using the autoregressive integrated moving average method. Only three cases required imputation of missing data, with two having less than 1% imputed and one having 6.2% imputed due to a couple of long periods when the actigraph was off-wrist during the daytime. Raw data were summed in hourly bins, and interdaily stability, intradaily variability, and relative amplitude of activity were calculated using locally-developed SPSS syntax and according to published formulas (Van Someren, 2007). We also calculated an autocorrelation coefficient (r24), which quantified the consistency of activity over a 24-hour time-lagged data. Autocorrelation compares activity levels from each minute of clock time across successive days (i.e., 12 :00 pm across days, 12:01 pm across days, and so forth). Stronger (closer to +1) autocorrelation indicated consistency of the timing of rest-activity patterns across days. Autocorrelation is a parametric equivalent to the non-parametric calculation interdaily stability. We examined both outcomes to compare our findings to prior research.

Results

Sample

This study reports on the results of eight participants, as one participant did not collect actigraphy data. The eight participants in this study were four women and four men with HIV. Their ages ranged from 39-53 years, with a mean of 48 years. Five identified as Caucasian, one as African American, and two as mixed race. Seven of the participants had completed high school, and three of those were college educated; all were currently unemployed. Two were in committed relationships. Modest use of street drugs was reported by two participants (1-2 days per week) and substantial substance use was reported by a third participant (alcohol multiple times per day, other drugs three times per week). All outcomes from the individual with daily substance use fell within the mid-range of the scores, so this individual was included in all analyses.

With one exception, all participants had been diagnosed with HIV more than 10 years ago (HIV diagnosis year ranged from 1988 – 2004). Viral load was undetectable for five participants and low (between 100-350 IU/L) for the other three participants. Mean hemoglobin level was 12.4 ± 2.4 mg/dL (range 9.2-15.4 mg/dL), and mean CD4+ T cell count was 413.5 ± 249.2 cells/mm3 (range 58-728 cells/mm3). Seven of the eight participants were currently taking antiretrovirals.

Sleep Outcomes

Sleep diaries

The sleep outcomes from the sleep diaries showed evidence of mild sleep disturbance in the eight participants (Table 1). Mean sleep onset latency was 34.5 ± 40.0 minutes, slightly exceeding the 30-minute threshold used in insomnia criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Mean WASO (21.1 ± 35.0 minutes) and total sleep time (7.9 ± 1.3 hours) were in the range considered normal, and sleep efficiency was slightly lower (84.9 ± 8.1%) than the commonly used threshold of 85-90% representing “good” sleep (Edinger et al., 2004).

Table 1.

7-Day Sleep and Rest-Activity Outcomes

| M | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep Diary | |||

| Sleep onset latency (minutes)a | 34.5 | 40.0 | 1.9 – 107.1 |

| Wake after sleep onset (minutes)b | 21.1 | 35.0 | 0 – 102.9 |

| Total sleep time (hours)c | 7.9 | 1.3 | 5.4 – 10.5 |

| Sleep efficiency (percentage)d | 84.9 | 8.1 | 69.7 – 91.1 |

| Sleep quality (self-rated scale, 1-5) | 2.5 | 0.4 | 2 – 3.14 |

| Actigraphy | |||

| Total wake time (minutes)e | 142.2 | 56.2 | 69.2 – 221.9 |

| Total sleep time (hours)c | 6.1 | 1.6 | 3.5 – 8.1 |

| Sleep efficiency (percentage)d | 72.4 | 12.6 | 48.2 – 86.6 |

| Rest-Activity Patterns Across and Within Days | |||

| RMSSD of bedtime (minutes)f | 32.6 | 28.6 | 0 – 91.6 |

| r24 (range 0-1)g | 0.33 | 0.07 | 0.19 – 0.40 |

| Interdaily stability (range 0-1)h | 0.48 | 0.12 | 0.33 – 0.63 |

| Intradaily variability (range 0-2)i | 0.71 | 0.20 | 0.48 – 1.13 |

| Relative amplitude (range 0-1)j | 0.90 | 0.07 | 0.66 – 0.95 |

Note. All data present the mean of 7 days of measurement. Root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD) was calculated from bedtimes reported in the sleep diaries. Interdaily stability, intradaily variability, relative amplitude, and r24 were calculated from 24-hour actigraphy data.

Sleep onset latency = minutes between going to bed and falling asleep.

Wake after sleep onset = minutes spent awake between initial sleep onset and final awakening.

Total sleep time = total hours in bed that are spent asleep.

Sleep efficiency = percentage of time in bed spent asleep.

Total wake time = total minutes in bed that are spent awake.

calculation of RMSSD is similar to standard deviation, except that RMSSD accounts for the time sequencing of the data. RMSSD provides information on the extent of variability in bedtime and rise time between adjacent days.

r24 = autocorrelation coefficient, which quantifies the consistency of activity over 24-hour time-lagged data. The closer the value is to one, the greater the consistency of activity patterns across days.

Interdaily stability = non-parametric calculation of the consistency of rest and activity patterns across days (similar to r24). Range is 0-1; closer to 0 represents less stability.

Intradaily variability = non-parametric calculation of the disorganization (i.e., variability) in rest and activity patterns within each day. Range is usually 0-2; higher values reflect more variability.

Relative amplitude = non-parametric calculation of the difference between the most active and least active time periods daily. High amplitude (values closer to 1) reflects more robust activity during time awake versus time at rest/asleep.

Actigraphy

Sleep outcomes showed significant sleep disturbance on actigraphy (Table 1). The mean for total wake time during time in bed was 142.2 ± 56.2 minutes, total sleep time was 6.1 ± 1.6 hours, and sleep efficiency was 72.4 ± 12.6%. Compared to subjective measures, which showed mild sleep disturbance, actigraphy showed substantial sleep disturbance with more than one fourth of the night being spent awake.

Variability of Sleep Timing

Analysis of bedtime and rise time

Bedtime and rise time showed substantial variability on the RMSSD analysis. The RMSSD of bedtime ranged from 0 to 91.7 minutes (mean = 32.6 ± 28.6 minutes), and the RMSSD of rise time ranged from 0 to 31.7 minutes (mean = 14.4 ± 11.1 minutes). Variability in bedtime (RMSSD) was strongly and significantly correlated with actigraphic outcomes of poorer sleep efficiency (r = −.785, p = .02) and higher wake time (r = .864, p = .006). Correlations between bedtime variability and actigraphic sleep onset latency (r = .582) and total sleep time (r = −.611) were not significant (p > .05), nor were correlations between bedtime variability and the sleep diary outcomes.

Rest-activity patterns

Rest-activity patterns refer to the regularity of the timing of sleep periods as well as the continuity of active and rest periods; that is, are there numerous rest periods during the day/active time, or are there numerous active episodes during rest/sleep time? In the treatment of insomnia it is recognized that unstable rest-activity patterns can disrupt sleep through unpredictability of psychological cues promoting the transition to rest at bedtime (Edinger & Means, 2005). Disorganized rest-activity patterns also disrupt sleep-regulating biological rhythms (Edinger & Means, 2005).

In this sample, we found that mean interdaily stability was 0.48 ± 0.12, intradaily variability was 0.71 ± 0.20, and relative amplitude was 0.90 ± 0.07. This value for interdaily stability is lower than values found in healthy persons (Huang et al., 2002) and persons with insomnia (Van Someren, 2007), indicating reduced consistency of rest–activity patterns from day to day. This was consistent with the RMSSD showing high variability of bedtimes and rise times, and was also consistent with the moderate autocorrelation of activity across days (r24 = 0.33 ± 0.07). Intradaily variability was lower than in other studies of healthy individuals (Huang et al., 2002) and in a similar range as persons with insomnia (Van Someren, 2007). This finding indicates that rest-activity patterns within days were generally well structured. Relative amplitude showed fairly robust magnitude of daytime versus nighttime activity levels. Overall, these findings indicate that the sample might benefit from interventions increasing the stability of sleep timing from day to day. Given the low within-day variability and high relative amplitude, addressing daytime activity does not seem needed by this sample.

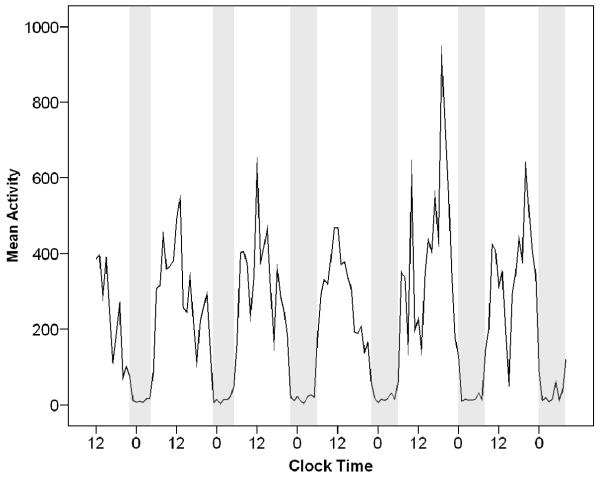

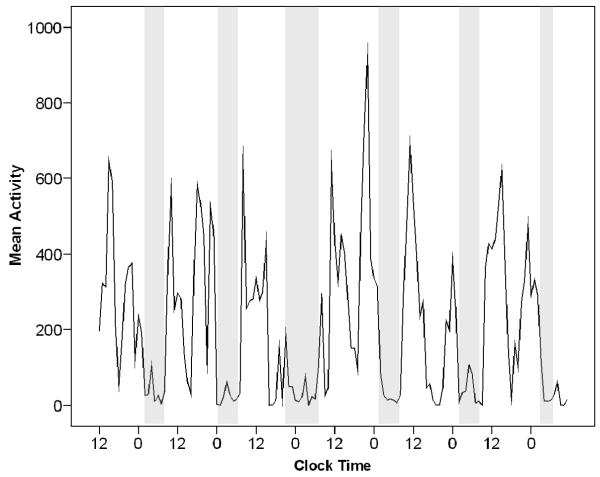

To illustrate the interdaily instability apparent in this sample, Figures 1 and 2 show activity levels over 1 week in two participants with different rest-activity patterns. On these graphs, clock time (12 = noon, 0 = midnight) is shown on the x-axis, and activity level measured by actigraph is shown on the y-axis. Time in bed is shown in the shaded areas.

Figure 1.

Participant with a well-defined and stable rest-activity pattern over 6 days. This figure shows a plot of activity over 6 days from a participant who sleeps fairly well. Rest (troughs on graph) and activity (peaks on the graph) are spaced at fairly regular intervals and are mostly consolidated (i.e., no frequent fluctuations between rest and activity are visible). This person slept about 7.5 hours each night, and sleep efficiency was 80% (still lower than the normal value of 85-90% or above). This individual might benefit from more consolidated sleep (i.e., increasing sleep efficiency) but the regularity of sleep timing would not need to be addressed. Note. Clock Time = 24-hour clock time (0 = midnight, 12 = noon) across successive days; Mean Activity = activity counts per minute on actigraphy; Grey area on the graph = time in bed.

Figure 2.

Participant with a variable and unstable rest-activity pattern over 6 days. This figure shows a plot of activity over 6 days from a participant who slept poorly and appeared to rest during the day. This person slept about 5.9 hours each night, and sleep efficiency was 77%. The participant had unstable patterns across days, visible in sleep periods of varying length and timing. The participant had high variability in activity during the day, apparent in the numerous transitions from high to low activity. This individual would benefit from more consistent sleep timing, more consolidated sleep at night, and more consolidated daytime activity.

Note. Clock Time = 24-hour clock time (0 = midnight, 12 = noon) across successive days; Mean Activity = activity counts per minute on actigraphy; Grey area on the graph = time in bed.

Figure 1 shows a plot of activity over 6 days measured by actigraphy from one of the study participants. This individual demonstrated only mild disruption of sleep and a fairly regular rest-activity pattern. This person slept about 7.5 hours each night and sleep efficiency was 80%. A clear day-night pattern is visible in the regular oscillation between inactivity at night (trough near 0) and activity during the day (peak levels on the graph). This individual would benefit from more consolidated sleep (i.e., increasing sleep efficiency) but the regularity of sleep time would not need to be addressed. In addition, this individual remained consistently active during the day, so activity patterns would not need to be addressed. For such an individual, short-term sleep medication might help to establish a less fragmented sleep pattern.

Figure 2 shows a plot of activity over 6 days measured by actigraphy from another study participant. This individual showed mild to moderately disrupted sleep and an irregular rest-activity pattern. This person slept about 5.9 hours each night, and sleep efficiency was 77%. The participant had unstable patterns across days, visible in sleep periods of varying length and timing. The participant had high variability in activity during the day, apparent in the numerous transitions from high to low activity. An appropriate treatment goal for this participant would be greater normalization of rest-activity timing; that is, help the individual organize his/her behavior to look more like Figure 1.

Discussion

This pilot study aimed to explore behavioral sleep patterns in a sample of chronically infected PLWH. Results from this study showed mild to moderate sleep disturbance on the sleep diaries, but significant sleep disturbance on actigraphy. Upon examination of variability in rest-activity patterns, we found substantial night-to-night variability in bedtime and rise time. The strong and significant correlation between bedtime variability and sleep disturbance (reduced sleep efficiency) indicated that stabilizing sleep timing might be an important intervention for improving sleep in this population. Analyses of 24-hour rest-activity patterns showed disorganization of rest/activity patterns across days (low interdaily stability) but stable and robust rest-activity patterns within days on the intradaily variability and relative amplitude. The latter findings suggest that increasing activity may not be a necessary treatment target for improving sleep in this type of population of PLWH. Overall, these findings support the need for assessing and treating sleep disturbance in PLWH. Furthermore, the sample in this study represented persons with well-managed HIV and low viral loads, indicating that sleep disturbances in PLWH may be attributable to factors other than HIV disease and suggesting that treatments for primary insomnia are well worth exploring.

This study corroborated prior findings of poor sleep on subjective and objective measures in persons with HIV (Reid & Dwyer, 2005), as well as demonstrating disorganized behavioral patterns around sleep. To our knowledge, this is the first study since Lee and colleagues (2001) to report objective sleep outcomes, which produced similar findings in a larger sample of women with HIV (N = 100). Lee and colleagues (2001) reported sleep disturbance on actigraphy, although somewhat less severe than observed in our study (total sleep time = 6.5 hours and sleep efficiency = 75%). Analysis of 24-hour rhythms by autocorrelation by Lee and colleagues (2001) showed moderate disorganization of rest-activity patterns (r24 = 0.40 ± 0.20), consistent with the results of our study (r24 = 0.33 ± 0.07). Lee and colleagues (2001) found evidence of frequent daytime napping. While we did not specifically ask participants to report naps, we found little evidence of daytime napping on actigraphy. The lack of napping behavior may be attributable to the regular activation of our participants through engagement in an HIV day-treatment program. Overall comparison of our findings to Lee and colleagues’ (2001) study suggested that, 10 years later, sleep disturbance remains a significant problem in persons with HIV, even if their disease is well managed.

In this study, we found greater evidence of sleep disturbance on actigraphy than in sleep diaries. This finding differed from the pattern common in persons with insomnia, who typically report greater subjective sleep disturbance than what is objectively measured (Means, Edinger, Glenn, & Fins, 2003). It is not possible to determine whether the discrepancies between actigraphy and sleep diaries were due to misperception of sleep or related to poor reporting. The diaries showed some evidence of back filling, which is when participants fill out data for all days at once rather than entering it daily. Signs of back filling include mislabeled dates, repeated values, and reported bedtimes and rise times that are misaligned with actigraphy (e.g., off by 1 day). If back filling is common in the population represented, diaries may not reflect the full extent of sleep disturbance in PLWH, potentially resulting in under-treatment of sleep disturbance. Given the small sample size, this issue bears further investigation, but it is worth recognizing that actigraphy may be useful in this population for confirming sleep patterns and quality.

The evidence of sleep disturbance related to irregular sleep timing supports the need for testing of behavioral therapies for insomnia in PLWH. Few studies have tested insomnia treatments in this population, and none have tested standard cognitive or behavioral therapies for insomnia. One pilot study tested a sleep hygiene treatment for women with HIV (n = 30), although the sample was not recruited for having sleep disturbance (Hudson, Portillo, & Lee, 2008). The treatment, which consisted of one 30-to 45-minute session on good sleep habits, significantly improved sleep in the subset of the sample experiencing baseline sleep disturbance. Another study tested the effect of caffeine reduction, a component of sleep hygiene, on sleep in men and women with HIV (n = 88; Dreher, 2003). Subjects randomized to gradual caffeine withdrawal had significant improvement in subjective sleep quality compared to those who continued their usual caffeine consumption.

Although these studies provide some initial support for behavioral treatment of sleep disturbance in PLWH, overall insomnia research does not support the efficacy of sleep hygiene alone (without other cognitive or behavioral interventions; Stepanski & Wyatt, 2003). However, standardized insomnia therapies, including cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia and brief behavioral therapy for insomnia, incorporate sleep hygiene as well as other behavioral principles and have been shown to be effective in a variety of populations with primary insomnia and insomnia co-morbid to medical conditions but have not been tested in PLWH (Stepanski & Rybarczyk, 2006). Although our study provided evidence of sleep-disrupting behaviors (e.g., varied sleep timing) in PLWH affected by such therapies, the feasibility of behavioral sleep treatments in this population remains unknown. Sleep timing may be difficult for persons whose sleep setting is shared or noisy, which is known to be problematic for persons with HIV (Nokes & Kendrew, 2001). In such situations, behavioral therapies for insomnia may require strategies to negotiate support from others, such as agreeing on a time when the living situation can be quiet and darkened to support sleep. This is an important area for further research.

Limitations

We have reported baseline sleep outcomes from a small pilot of a mind-body therapy for PLWH. Given the small sample size, the findings should be interpreted cautiously. The findings from this small sample of persons with well-managed disease and frequent socialization may not be generalizable to other groups of PLWH. One would expect PLWH who do not receive effective disease management or regular socialization to experience at least the degree of sleep disturbance shown in this study; the validity of the outcomes from this study is supported by consistency with prior studies of sleep in PLWH, particularly the sleep and rest-activity outcomes from the study by Lee and colleagues (2001), who also used actigraphy. However, there is no evidence suggesting whether or not persons without good disease management or socialization would have the same behavioral patterns contributing to sleep disturbance (i.e., variable sleep timing).

Given that sleep was not the primary outcome of this pilot study, we did not fully explore the reasons for the sleep disturbances and behaviors observed. These are priorities for future research. The effect of alcohol or street drugs on sleep was not examined in this small sample, and this area currently lacks sufficient descriptive research. In addition, we did not exclude all persons with primary sleep disorders (sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, etc.). Two participants had known sleep apnea that was treated by continuous positive airway pressure; two participants had symptoms suspicious for sleep apnea and also reported symptoms of restless legs syndrome. Those individuals with sleep apnea or restless legs syndrome did not show a clear pattern of worse sleep than those without these problems, so it seems unlikely that inclusion of these participants significantly biased the results of the study.

Conclusions and Implications

Sleep disturbance has long been recognized as a significant problem affecting the quality of life and health outcomes in PLWH. However, few studies have examined targets for effective treatments. This study adds to the body of literature demonstrating significant degrees of sleep disturbance in a sample of PLWH. Results also showed greater sleep disturbance on objective (actigraphy) than subjective (sleep diaries) measures, suggesting that actigraphy may be useful for revealing the full extent of sleep disturbance in PLWH. Furthermore, we found evidence of high variability of sleep timing. These findings support further research on factors contributing to poor sleep quality and behavioral disorganization of sleep in PLWH. Results from our study suggest that behavioral treatment for insomnia may be useful for PLWH, particularly brief behavioral therapy for insomnia, which is delivered over a short period of time (4 weeks) and emphasizes normalization of sleep timing (Buysse et al., 2011). Research is needed to support the feasibility of behavioral treatments in this population and potential need for population-specific tailoring of such interventions.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a grant from the University of Washington School of Nursing Research and Intramural Funding Program and by NR 011400 (Center for Research on the Management of Sleep Disturbance). This was not an industry supported study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors report no real or perceived vested interests that relate to this article (including relationships with pharmaceutical companies, biomedical device manufacturers, grantors, or other entities whose products or services are related to topics covered in this manuscript) that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

None of the authors has a financial conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Diana M. Taibi, Departments of Biobehavioral Nursing & Health Systems University of Washington Seattle, WA, USA..

Cynthia Price, Departments of Biobehavioral Nursing & Health Systems University of Washington Seattle, WA, USA..

Joachim Voss, Departments of Biobehavioral Nursing & Health Systems University of Washington Seattle, WA, USA..

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed American Psychiatric Publishing; Washington, D.C.: 1994. Sleep disorders; pp. 597–661. [Google Scholar]

- Aouizerat BE, Miaskowski CA, Gay C, Portillo CJ, Coggins T, Davis H, Lee KA. Risk factors and symptoms associated with pain in HIV-infected adults. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2010;21(2):125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.10.003. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Germain A, Moul DE, Franzen PL, Brar LK, Fletcher ME, Monk TH. Efficacy of brief behavioral treatment for chronic insomnia in older adults. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2011;171(10):887–895. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen FL, Ferrans CE, Vizgirda V, Kunkle V, Cloninger L. Sleep in men and women infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Holistic Nursing Practice. 1996;10(4):33–43. doi: 10.1097/00004650-199607000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruess DG, Antoni MH, Gonzalez J, Fletcher MA, Klimas N, Duran R, Schneiderman N. Sleep disturbance mediates the association between psychological distress and immune status among HIV-positive men and women on combination antiretroviral therapy. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2003;54(3):185–189. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00501-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreher HM. The effect of caffeine reduction on sleep quality and well-being in persons with HIV. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2003;54(3):191–198. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00472-5. doi.10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00472-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edinger JD, Bonnet MH, Bootzin RR, Doghramji K, Dorsey CM, Espie CA, Stepanski EJ. Derivation of research diagnostic criteria for insomnia: Report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Work Group. Sleep. 2004;27(8):1567–1596. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.8.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edinger JD, Means MK. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for primary insomnia. Clinical Psychology Reviews. 2005;25(5):539–558. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.04.003. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumaz CR, Tuldra A, Ferrer MJ, Paredes R, Bonjoch A, Jou T, Clotet B. Quality of life, emotional status, and adherence of HIV-1-infected patients treated with efavirenz versus protease inhibitor-containing regimens. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes and Human Retroviorology. 2002;29(3):244–253. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200203010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YL, Liu RY, Wang QS, Van Someren EJ, Xu H, Zhou JN. Age-associated difference in circadian sleep-wake and rest-activity rhythms. Physiology and Behavior. 2002;76(4-5):597–603. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00733-3. doi:10.1016/S0031-9384(02)00733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson AL, Portillo CJ, Lee KA. Sleep disturbances in women with HIV or AIDS: Efficacy of a tailored sleep promotion intervention. Nursing Research. 2008;57(5):360–366. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000313501.84604.2c. doi:10.1097/01.NNR.0000313501.84604.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KA, Portillo CJ, Miramontes H. The influence of sleep and activity patterns on fatigue in women with HIV/AIDS. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2001;12(Suppl.):19–27. doi: 10.1177/105532901773742257. doi:10.1016/S1055-3290(06)60154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Means MK, Edinger JD, Glenn DM, Fins AI. Accuracy of sleep perceptions among insomnia sufferers and normal sleepers. Sleep Medicine. 2003;4(4):285–296. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(03)00057-1. doi:10.1016/S1389-9457(03)00057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin CM, Bootzin RR, Buysse DJ, Edinger JD, Espie CA, Lichstein KL. Psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: Update of the recent evidence (1998-2004) Sleep. 2006;29(11):1398–1414. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.11.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin CM, Espie CA. Insomnia: A clinical guide to assessment and treatment. Springer; New York, NY: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Moyle G, Fletcher C, Brown H, Mandalia S, Gazzard B. Changes in sleep quality and brain wave patterns following initiation of an efavirenz-containing triple antiretroviral regimen. HIV Medicine. 2006;7(4):243–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2006.00363.x. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1293.2006.00363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nokes KM, Kendrew J. Correlates of sleep quality in persons with HIV disease. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2001;12(1):17–22. doi: 10.1016/S1055-3290(06)60167-2. doi:10.1016/S1055-3290(06)60167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf.

- Phillips KD, Moneyham L, Murdaugh C, Boyd MR, Tavakoli A, Jackson K, Vyavaharkar M. Sleep disturbance and depression as barriers to adherence. Clinical Nursing Research. 2005;14(3):273–293. doi: 10.1177/1054773805275122. doi:10.1177/1054773805275122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KD, Sowell RL, Boyd M, Dudgeon WD, Hand GA. Sleep quality and health-related quality of life in HIV-infected African-American women of childbearing age. Quality of Life Research. 2005;14(4):959–970. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-2574-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid S, Dwyer J. Insomnia in HIV infection: A systematic review of prevalence, correlates, and management. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67(2):260–269. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000151771.46127.df. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000151771.46127.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins JL, Phillips KD, Dudgeon WD, Hand GA. Physiological and psychological correlates of sleep in HIV infection. Clinical Nursing Research. 2004;13(1):33–52. doi: 10.1177/1054773803259655. doi:10.1177/1054773803259655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein ML, Selwyn PA. High prevalence of insomnia in an outpatient population with HIV infection. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 1998;19(3):260–265. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199811010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salahuddin N, Barroso J, Leserman J, Harmon JL, Pence BW. Daytime sleepiness, nighttime sleep quality, stressful life events, and HIV-related fatigue. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2009;20(1):6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2008.05.007. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutte-Rodin S, Broch L, Buysse D, Dorsey C, Sateia M. Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2008;4(5):487–504. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanski EJ, Rybarczyk B. Emerging research on the treatment and etiology of secondary or comorbid insomnia. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2006;10(1):7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.08.002. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanski EJ, Wyatt JK. Use of sleep hygiene in the treatment of insomnia. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2003;7(3):215–225. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0246. doi:10.1053/smrv.2001.0246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Someren EJ. Improving actigraphic sleep estimates in insomnia and dementia: How many nights? Journal of Sleep Research. 2007;16(3):269–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2007.00592.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2869.2007.00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Montaner J. The urgency of providing comprehensive and integrated treatment for substance abusers with HIV. Health Affairs. 2011;30(8):1411–1419. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0663. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zammit G. Comparative tolerability of newer agents for insomnia. Drug Safety. 2009;32(9):735–748. doi: 10.2165/11312920-000000000-00000. doi:10.2165/11312920-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]