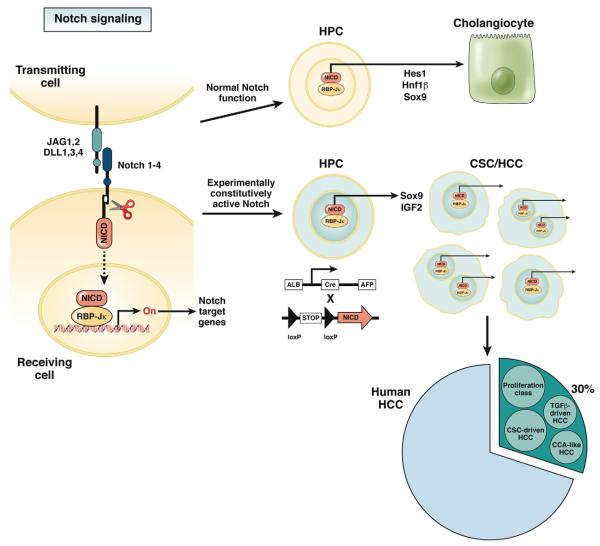

Notch signaling is a complex, highly conserved mechanism, originally discovered as critical regulator of cell fate determination during development in several tissues and organs.1,2 Activation of Notch may stimulate cells either to undergo a phenotypic switch or to maintain the original cell phenotype by preventing further differentiation,3 Notch is also involved in establishing organ-specific stem cell niches necessary for epithelial tissue homeostasis.3,4 The Notch system encompasses 4 genes encoding for different membrane receptors (Notch 1, 2, 3, and 4), which are activated by their binding to 5 ligands (Jagged-1, Jagged-2, and Delta-like 1, 3, and 4).4 Cell-to-cell contact is a prerequisite for the activation of Notch signaling.3,4 Whereas Notch receptors are expressed by the “receiver” cell, ligands are expressed by the “transmitter” cell. This interaction leads to the proteolytic cleavage and subsequent nuclear translocation of the intracellular domain of Notch receptors (NICD). Once migrated into the nucleus, NICD associates with the nuclear protein of the RBP-Jκ family and transcriptionally activates several other transcriptional activators or repressors that act as critical regulators of cell differentiation, apoptosis, and proliferation4 (see drawing on the left side of Figure 1). NICD is then rapidly deactivated by phosphorylation and by proteosomal degradation. The signal is maintained through ligand-induced proteolytic supply of new NICD.

Figure 1.

Effects of Notch activation in hepatic progenitor cells in normal and experimental conditions. Activation of Notch signaling requires the close contact between Notch-expressing “receiving” cells and Jag/Dll-expressing “transmitting” cells. This interaction leads to the proteolytic cleavage and subsequent nuclear translocation of the NICD. By associating with the nuclear protein of the RBP-Jκ family, NICD transcriptionally activates several Notch target genes acting as critical regulators of cell differentiation and proliferation. In normal conditions, transient Notch activation in hepatic progenitor cells enables them to differentiate into cholangiocytes by inducing the expression of transcription factors critical for biliary lineage (including Hes-1, HNF1β, and Sox9). In experimental conditions, constitutional activation of Notch generated by inducing the AFP-Cre–mediated overexpression of NICD1 in embryonic hepatic progenitor cells, leads to the generation of HCC showing some features of CSC activation. Sox9 and IGF2 are critical modulators of NICD1-induced liver carcinogenesis. Signatures of Notch activation can be found in about 30% of patients with HCC. In these patients, the Notch signature co-clustered with specific molecular subgroups of HCC, mainly including the “proliferation class” and an “CSC-driven” HCC. In addition, a “CCA-like” HCC and a “TGFβ-driven” HCC are also associated with the Notch signature. CCA, cholangiocarcinoma; CSC, cancer stem cell; DLL, delta-like; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HPC, hepatic progenitor cell; JAG, Jagged; NICD, Notch intracellular domain.

Activation of Notch is essential for ductal plate remodeling and tubulogenesis, the principal steps of bile duct ontogenesis.5,6 In response to signals from the periportal mesenchyme, Notch regulates the ability of hepatoblasts to differentiate into duct plate cells and form branching tubules by inducing the expression of transcription factors critical for biliary specification (including Hes-1, HNF1β, and Sox9), and down-regulating the expression of HNF1α and HNF4 (see normal Notch function as indicated in the upper right side of Figure 1). In Alagille syndrome, a genetic condition of defective Notch signaling, paucity of bile ducts is associated with impaired biliary differentiation of hepatic progenitor cells (HPC), suggesting that Notch may also act as an important modulator of liver repair in adult life.7 In liver diseases, activation/inhibition of Notch in HPC and their subsequent biliary/hepatocyte specification is finely orchestrated by HPC interaction with the stromal microenvironment or with infiltrating macrophages, through Jagged1 and Numb, respectively.8

Recently, the role of Notch signaling in carcinogenesis has received considerable interest. An oncogenic role for Notch signaling in human cancer was first demonstrated in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, where gain-of-function mutations in the NOTCH1 gene induced an increased stability of NICD1, resulting in the constitutional activation of the Notch pathway. By preventing their differentiation, continuous activation of Notch signaling predisposes undifferentiated T cells to neoplastic transformation.9 In contrast, evidence for genetic alterations in the NOTCH genes has been reported only sporadically in solid tumors (salivary gland, lung, skin).10 In these tumors, the inappropriate activation of Notch is caused by a dysbalance between Notch ligands, such as Jagged1, that can be aberrantly overexpressed, and inhibitors, such as FBXW7, Numb, or Deltex, which can be defective, as reported in breast11,12 and colorectal cancer.13 To add further complexity, Notch signaling may generate opposing effects on different steps of carcinogenesis, depending on the tumor cell type and the status of other signaling pathways, including morphogens (Wnt), tumor suppressors (p53), and growth factors.10

Similar to other forms of solid tumors, conflicting results have been reported on the role of Notch in liver cancer. Qi et al in 200314 demonstrated that overexpression of Notch1, acting on different cell cycle regulators (cyclin A1, cyclin D1, cyclin E, CDK2, retinoblastoma protein), inhibited proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells by inducing a G0/G1 cell cycle arrest. Notch1 was shown to induce apoptosis of HCC cells by altering the balance between p53 and Bcl-2. The same authors showed that up-regulation of p53 induced by Notch1 sensitized HCC cells to tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand–induced apoptosis.15 Furthermore, in mouse models of HCC generated by genetic inactivation of the retinoblastoma pathway, activation of the Notch signaling reduced HCC cell proliferation and tumor growth.16 Notably, in the same study, dataset analysis of HCC patients showed that higher expression levels of NOTCH1 genes were associated with better survival. At odds with these findings, some recent studies have provided strong evidence in favor of the pro-oncogenic activity of Notch in HCC. Giovannini et al17 reported aberrant nuclear expression of Notch1 and Notch3 in neoplastic hepatocytes compared with the surrounding cirrhotic tissue. Furthermore, silencing of Notch3 in HCC cells enhanced sensitivity to doxorubicin-induced cell death via a p53-dependent mechanism. Lim et al18 found that in cells overexpressing wild-type p53, coordinated activation of the Notch1-Snail axis was associated with an increased invasiveness and dedifferentiation of HCC cells. More recently, Liu et al19 showed that tumor necrosis factor-α, via IKKα and the FOXA2 transcription factor, reduced the expression of the Notch suppressor, Numb. Suppression of FOXA2 is a distinctive feature of many inflammatory conditions, and may represent a molecular link between chronic inflammation and cancer. These studies highlight the concept that in HCC, the oncogenic role of Notch signaling is dependent on the cooperation with other pathways (p53, Snail, TNFα/IKKα/FOXA2/NUMB), often modulated by the local inflammatory microenvironment.

The work from Villanueva et al, published in this issue of Gastroenterology,20 provides new, important clues to understand the complex role of Notch in HCC. The authors followed an innovative, comparative, functional genomics approach aimed at identifying common pathogenetic features of human cancer and mouse models targeting specific pathways. The authors observed that, by the age of 12 months, all mice constitutively overexpressing NICD1 in liver epithelial cells developed liver tumors with histologic features consistent with HCC. In these mice, generated by inducing the AFP-Cre–mediated overexpression of NICD1 in embryonic hepatoblasts, a latency time of >6 months was observed before the development of HCC, indicating the requirement of additional hits to induce cell transformation, a behavior shown by many oncogenes.10 In this experimental model, different histologic stages of human hepatocarcinogenesis were reproduced (from normal to malignant hepatocytes), including dysplastic nodules and lesions compatible with activation of HPC. By studying the transcriptomic profile of Notch-induced HCC in mice, the authors generated a 384-gene signature that was then analyzed in >600 human HCC samples derived from different etiologies and studies. Signatures consistent with Notch activation were observed in a subgroup of HCC patients (around 30%), regardless of the etiology and of tumor stage. Notch effects on cell transformation were likely related to stimulation of cell proliferation, since HCC featuring Notch activation showed an enrichment in genomic signals related to cell-cycle progression. In fact, selective Notch inhibition in HCC cell lines by lentiviral vectors or pharmacologic agents resulted in growth inhibition.

The limited subset of HCC patients featuring Notch activation further supports the concept that the effects of Notch signaling in HCC are heterogeneous, being highly context dependent and relying on the cooperation of additional oncogenic pathways. In this study, IGF2 and Sox9 have been identified as critical “oncogenic partners” of activated Notch in both experimental and human HCC. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF) signaling was found to be induced via reactivation of the fetal IGF2 promoter. IGF2 is an oncogene strongly involved in tumorigenesis, as previously reported in breast, ovarian and colorectal cancers, where it promotes cell proliferation and survival.21 IGF2 stimulates the growth of HepG2 cells22 and its up-regulation is a well-known feature of human HCC, where it identifies a specific molecular subclass.23 Recently, up-regulation of IGF2 signaling has been found in cancer stem cells (CSC) of HCC in association with Nanog, a transcription factor expressed by embryonic stem cells. Through the IGF pathway, Nanog promotes the self-renewal abilities of CSC in HCC.24 Similar to IGF2, Sox9 (a Notch-target gene) has also been associated with CSC. In cooperation with Slug, a transcription factor regulating the maintenance of embryonic stem cell functions, Sox9 orchestrates the dedifferentiation of mammary epithelial cells into a stem cell state.25 In the liver, Sox9 is expressed by HPC.26 In summary, these observations are consistent with the histologic features of progenitor cell activation that are seen in those HCC related to Notch activation. As suggested by the authors, Notch could be involved in HCC by expanding a preexisting population of HPC (later becoming CSC) and/or by inducing differentiated hepatocytes to gain a progenitor cell-like phenotype (see constitutional activation of Notch as illustrated in the lower right side of Figure 1). This novel hypothesis identifies Notch signaling as a molecular pathway possibly involved in the development of CSC-driven HCC.

In conclusion, the study from Villanueva et al20 sheds new light on the evolving dilemma concerning the ambivalent role of Notch in liver carcinogenesis and clearly shows the oncogenic role of the continuous activation of Notch in the liver of experimental models. In humans, this seems to be limited to a specific subset of HCC patients. In these cases, Notch effects are strictly dependent on the molecular context, where IGF2 and Sox9 behave as critical partners supporting the pro-oncogenic functions of Notch1. Notch represents a novel potential target in a subset of HCC patients that reaches beyond the molecular-targeted therapies proposed for HCC so far.

Acknowledgments

Funding Supported by NIH DK079005 and by PSC Partner for a cure to MS, by the NIH Yale Liver Center, P30 DK34989. Telethon (GGP 09189) and Ateneo (CPD 113799/11) Grant support to LF is also gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Contributor Information

MARIO STRAZZABOSCO, Section of Digestive Diseases Yale University New Haven, Connecticut and Department of Clinical Medicine University of Milan-Bicocca Milan, Italy.

LUCA FABRIS, Department of Clinical Medicine University of Milan-Bicocca Milan, Italy and Department of Surgery, Oncology and Gastroenterology University of Padova Padova, Italy Division of Gastroenterology Regional Hospital Treviso Treviso, Italy.

References

- 1.Lorent K, Yeo SY, Oda T, et al. Inhibition of Jagged-mediated Notch signaling disrupts zebrafish biliary development and generates multi-organ defects compatible with an Alagille syndrome phenocopy. Development. 2004;131:5753–5766. doi: 10.1242/dev.01411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lozier J, McCright B, Gridley T. Notch signaling regulates bile duct morphogenesis in mice. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1851. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cornell RA, Eisen JS. Notch in the pathway: the roles of Notch signaling in neural crest development. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:663–672. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gridley T. Notch signaling and inherited disease syndromes. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:R9–R13. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kodama Y, Hijikata M, Kageyama R, et al. The role of notch signaling in the development of intrahepatic bile ducts. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1775–1786. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lemaigre FP. Mechanisms of liver development: concepts for understanding liver disorders and design of novel therapies. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:62–79. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fabris L, Cadamuro M, Guido M, et al. Analysis of liver repair mechanisms in Alagille syndrome and biliary atresia reveals a role for notch signaling. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:641–653. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boulter L, Govaere O, Bird TG, et al. Macrophage-derived Wnt opposes Notch signaling to specify hepatic progenitor cell fate in chronic liver disease. Nat Med. 2012;18:572–579. doi: 10.1038/nm.2667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellisen LW, Bird J, West DC, et al. TAN-1, the human homolog of the Drosophila notch gene, is broken by chromosomal translocations in T lymphoblastic neoplasms. Cell. 1991;66:649–661. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90111-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ranganathan P, Weaver KL, Capobianco AJ. Notch signalling in solid tumours: a little bit of everything but not all the time. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:336–351. doi: 10.1038/nrc3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen B, Shimizu M, Izrailit J, et al. Cyclin D1 is a direct target of JAG1-mediated Notch signaling in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:113–124. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0621-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pece S, Serresi M, Santolini E, et al. Loss of negative regulation by Numb over Notch is relevant to human breast carcinogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:215–221. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200406140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyaki M, Yamaguchi T, Iijima T, et al. Somatic mutations of the CDC4 (FBXW7) gene in hereditary colorectal tumors. Oncology. 2009;76:430–434. doi: 10.1159/000217811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qi R, An H, Yu Y, et al. Notch1 signaling inhibits growth of human hepatocellular carcinoma through induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8323–8329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang C, Qi R, Li N, et al. Notch1 signaling sensitizes tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis inducing ligand-induced apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells by inhibiting Akt/Hdm2-mediated p53 degradation and up-regulating p53-dependent DR5 expression. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:16183–16190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.002105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 16.Viatour P, Ehmer U, Saddic LA, et al. Notch signaling inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma following inactivation of the RB pathway. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1963–1976. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giovannini C, Gramantieri L, Chieco P, et al. Selective ablation of Notch3 in HCC enhances doxorubicin’s death promoting effect by a p53 dependent mechanism. J Hepatol. 2009;50:969–979. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim S-O, Park YM, Kim HS, et al. Notch1 differentially regulates oncogenesis by wildtype p53 overexpression and p53 mutation in grade III hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2011;53:1382–1392. doi: 10.1002/hep.24208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu M, Lee D-F, Chen C-T, et al. IKKα activation of NOTCH links tumorigenesis via FOXA2 suppression. Mol Cell. 2012;45:171–184. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Villanueva A, Alsinet C, Yanger K, et al. Notch signaling is activated in human hepatocellular carcinoma and induces tumor formation in mice. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1660–1669. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clermont F, Nittner D, Marine JC. IGF2: the Achilles’ heel of p53-deficiency? EMBO Mol Med. 2012;4:688–690. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201201509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strazzabosco M, Poci C, Spirlì C, et al. Intracellular pH regulation in Hep G2 cells: effects of epidermal growth factor, transforming growth factor-alpha, and insulin like growth factor-II on Na+/H+ exchange activity. Hepatology. 1995;22:588–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tovar V, Alsinet C, Villanueva A, et al. IGF activation in a molecular subclass of hepatocellular carcinoma and pre-clinical efficacy of IGF-1R blockage. J Hepatol. 2010;52:550–559. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shan J, Shen J, Liu L, et al. Nanog regulates self-renewal of cancer stem cells through the insulin-like growth factor pathway in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2012;56:1004–1014. doi: 10.1002/hep.25745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo W, Keckesova Z, Donaher JL, et al. Slug and Sox9 cooperatively determine the mammary stem cell state. Cell. 2012;148:1015–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Furuyama K, Kawaguchi Y, Akiyama H, et al. Continuous cell supply from a Sox9-expressing progenitor zone in adult liver, exocrine pancreas and intestine. Nat Genet. 2011;43:34–41. doi: 10.1038/ng.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]