Abstract

Background

Bipolar disorder is a serious mental illness, characterized by frequent recurrences and major comorbidities. Its consequences can include suicide.

Methods

An S3 guideline for the treatment of bipolar disorder was developed on the basis of a systematic literature search, evaluation of the retrieved publications, and a formal consensus-finding procedure. Several thousand publications were screened, and 611 were included in the analysis, including 145 randomized controlled trials (RCT).

Results

Bipolar disorder should be diagnosed as early as possible. The most extensive evidence is available for pharmacological monotherapy; there is little evidence for combination therapy, which is nonetheless commonly given. The appropriate treatment may include long-term maintenance treatment, if indicated. The treatment of mania should begin with one of the recommended mood stabilizers or antipsychotic drugs; the number needed to treat (NNT) is 3 to 13 for three weeks of treatment with lithium or atypical antipsychotic drugs. The treatment of bipolar depression should begin with quetiapine (NNT = 5 to 7 for eight weeks of treatment), unless the patient is already under mood-stabilizing treatment that can be optimized. Further options in the treatment of bipolar depression are the recommended mood stabilizers, atypical antipsychotic drugs, and antidepressants. For maintenance treatment, lithium should be used preferentially (NNT = 14 for 12 months of treatment and 3 for 24 months of treatment), although other mood stabilizers or atypical antipsychotic drugs can be given as well. Psychotherapy (in addition to any pharmacological treatment) is recommended with the main goals of long-term stabilization, prevention of new episodes, and management of suicidality. In view of the current mental health care situation in Germany and the findings of studies from other countries, it is clear that there is a need for prompt access to need-based, complex and multimodal care structures. Patients and their families need to be adequately informed and should participate in psychiatric decision-making.

Conclusion

Better patient care is needed to improve the course of the disease, resulting in better psychosocial function. There is a need for further high-quality clinical trials on topics relevant to routine clinical practice.

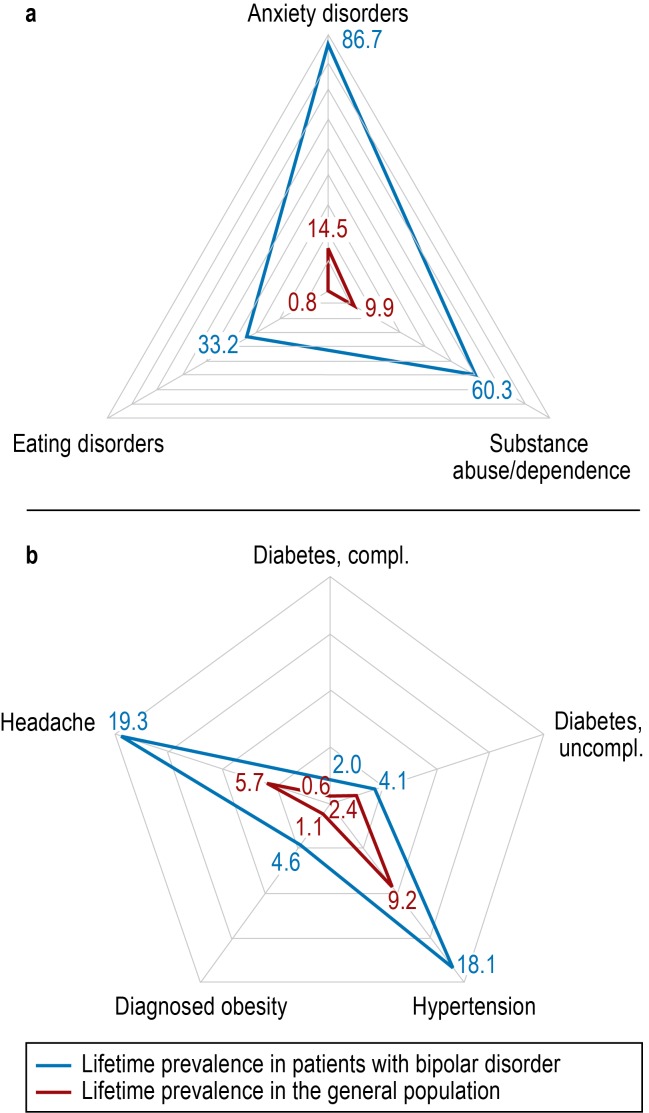

Bipolar disorder is a severe psychiatric disease with a lifetime prevalence of 3% (1), characterized by frequent recurrences and considerable psychiatric and somatic comorbidity. Suicidality is common, and the disease has substantial consequences both for the individual and for health care spending (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of lifetime prevalence (%) of selected psychiatric (a) and somatic (b) diseases in patients with bipolar disorder compared with the general population

a) data from (1) and (17) for patients with bipolar disorder and from (16) for the general population

b) data from (18)

The project to create the first German-language evidence- and consensus-based guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorders was initiated in 2007 by the German Society for Bipolar Disorder (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Bipolare Störungen, DGBS) and the German Association for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie, Psychotherapie und Nervenheilkunde, DGPPN), with the intention of providing decision-making support for patients, their families, and therapists. Assistance was provided by the Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften, AWMF; www.awmf.org). The guideline was developed without any funding from manufacturers of pharmaceuticals or medical devices.

Here we give a brief account of the development and essential content of the guideline. The full version of the guideline (2) is available (in German) at www.leitlinie-bipolar.de.

Methods

A project group, a steering group, six different working groups and the consensus conference all participated actively in the guideline process (Table 1). The extended review procedure also involved a review group and an expert panel. The participants are listed in full in the eSupplement.

Table 1. Composition of the consensus conference.

| Voting members of the consensus conference* | ||

| German Society for Bipolar Disorder (DGBS) | Prof. Michael Bauer | |

| German Association for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy (DGPPN) | Prof. Peter Falkai, | |

| Prof. Oliver Gruber | ||

| Professional Association of German Psychiatrists (BVDP) | Dr. Lutz Bode | |

| Professional League of German Neurologic Medicine (BVDN) | Dr. Roland Urban | |

| German Psychological Society (DGPs) | Prof. Martin Hautzinger, | |

| Prof. Thomas D. Meyer | ||

| German Federal Conference of Psychiatric Hospital Directors (BDK) | Prof. Lothar Adler, | |

| Dr. Harald Scherk | ||

| German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians (DEGAM) | Dipl.-Soz. Martin Beyer | |

| Working Group of Directors of Psychiatric Departments at General Hospitals in Germany (ACKPA) | Dr. Günter Niklewski | |

| Drug Commission of the German Medical Association (AkdÄ) | Dr. Tom Bschor | |

| DGBS Self-Help Network | Dietmar Geissler | |

| Federal Organisation of (ex-)Users and Survivors of Psychiatry in Germany (BPE) | Reinhard Gielen | |

| DGBS Families Initiative | Horst Giesler | |

| Federal Association of Relatives of the Mentally Ill (BApK) | Karl Heinz Möhrmann | |

| Representative of Diagnosis Working Group | Prof. Peter Bräunig | |

| Representative of Pharmacotherapy Working Group | Dr. Johanna Sasse | |

| Representative of Psychotherapy Working Group | Prof. Thomas D. Meyer | |

| Representatives of Nonmedicinal Somatic Procedures Working Group | Dr. Frank Padberg, | |

| Dr. Thomas Baghai | ||

| Representatives of the Working Group Health Care System | Prof. Peter Brieger, | |

| Prof. Andrea Pfennig | ||

*Each organisation and working group had one vote (total: 18 votes)

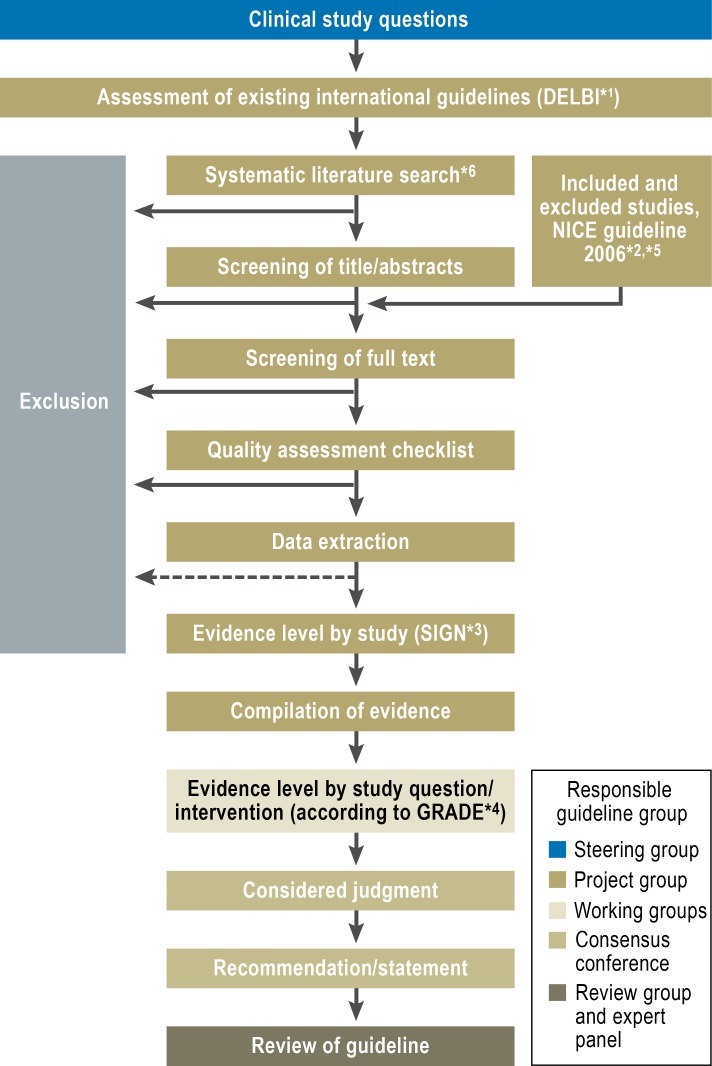

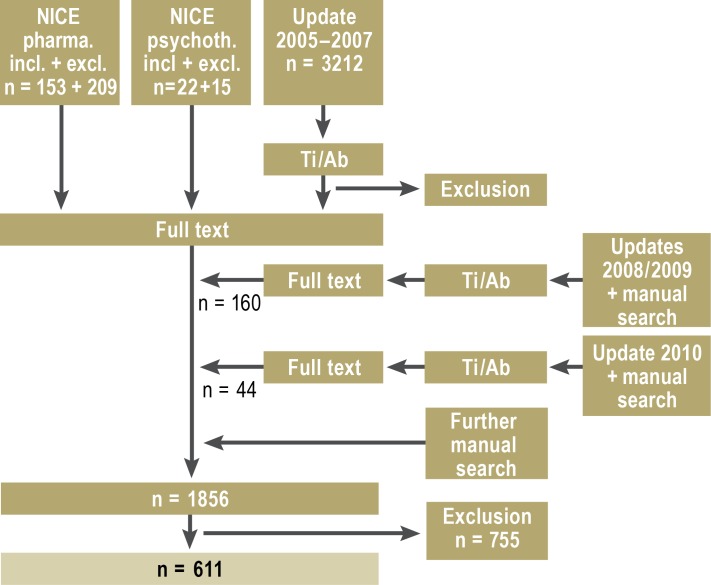

Figure 2 outlines the guideline development process, and an overview of the literature search, showing the number of publications included and excluded, is given in Figure 3. Several thousand publications found in MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and the Cochrane Library were screened, and 611 publications on the following topics were selected for inclusion:

Figure 2.

Guideline development process with responsible guideline groups

*1German Instrument for Methodical Guideline Assessment (Deutsches Instrument zur methodischen Leitlinien-Bewertung, DELBI) (19)

*2The management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and adolescents, in primary and secondary care, NICE 2006 (20)

*3Guidelines of the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network Grading Review Group, Keaney (21), Lowe (22)

*4Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) (23)

*5Literature up to mid-2005

*6Starting in 2005, modified search using NICE search criteria + search for additional study questions

Figure 3.

Overview of literature search and criteria for inclusion and exclusion. Ti/Ab: screening of titles and (if present) abstracts

Treatment of mania

Treatment of bipolar depression

Randomized controlled trials (RCT; n = 145) on maintenance treatment.

All relevant studies identified (primarily randomized clinical trials referring to patients with bipolar disorder, or presenting separate results for this patient group) were critically assessed. The end points regarded as particularly relevant were: psychopathology or severity of symptoms; dropouts overall; dropouts owing to adverse effects; important adverse effects; and quality of life. Each of the six working groups included both hospital-based psychiatrists and psychotherapists, and psychiatrists and psychotherapists working outside the hospital setting, as well as representatives of patients and their families. Over the course of ten consensus conferences, 232 recommendations and statements were discussed and approved in a nominal group process involving representatives of 13 scientific medical societies, professional associations and other organizations together with five experts. The grades of recommendation assigned in the S3 Guideline are listed in Box 1.

Box 1. Recommendation grades*.

A (strong recommendation) (“must”)

B (simple recommendation) (“should”)

0 (recommendation open) (“can”)

CCP (clinical consensus point): for questions that cannot be expected to be resolved by studies, e.g., on ethical grounds or because the necessary methods cannot be implemented; equivalent to evidence-based recommendation grades A to 0, the strength of recommendation being expressed in the wording

Statement: for questions on which, for example, no adequate evidence was found but nevertheless a statement should be put down

*In agreement with the AWMF definitions

Some of the statements and recommendations are given here in summarized and abridged form and thus deviate from the original wording.

Detailed description and discussion of the methods can be found in (2– 4).

Diagnosis and documentation of disease course

Accurate diagnosis is the key to adequate treatment and best possible maintenance of the patient’s occupational and social function. ICD-10 demands identification of at least two clearly distinct affective episodes. The validity of the diagnosis thus increases as the disease progresses.

Affective episodes can be characterized by manic, hypomanic, depressive, or mixed syndromes (Table 2).

Table 2. Description of clinical episodes according to ICD-10.

| Episode | Duration | Principal symptoms | Number of symptoms required |

| Manic | ≥ 1 week | Elevated, expansive or irritable mood | 3 of the following 9 further symptoms (4 if "irritable" mood is the principal symptom): increased energy, compulsion to talk, flight of ideas, reduced social inhibition, decreased need for sleep, inflated self-confidence, distractibility, reckless behavior, increased libido |

| Hypomanic | ≥ 4 days | Elevated or irritable mood | 3 of 7 further symptoms (increased activity or motor restlessness, increased talkativeness, concentration difficulties or distractibility, decreased need for sleep, increased libido, exaggerated shopping or other careless or irresponsible behavior, increased sociability or excessive familiarity) |

| Depressive | ≥ 2 weeks | Depressive mood, lack of interest, decreased energy | 4 of 10 symptoms (at least 2 of them principal symptoms)Further symptoms: loss of self-esteem, inappropriate feelings of guilt, repeated thoughts of death or suicidality, cognitive deficits, psychomotor changes, sleep disorders, appetite disorders |

| Mixed | ≥ 2 weeks | Mixed or alternating depressive and (hypo)manic symptoms | Unspecified |

In addition to classifying the disease, the diagnostic process should have a dimensional aspect describing the severity of the symptoms. Validated instruments are available for both self-assessment and external evaluation of mania and depression (see the full version of the guideline). These instruments should preferably be applied more than once (recommendation grade: statement).

One complicating factor in the diagnosis of bipolar disorder is that the disease often begins with episodes of depression; hypomanic symptoms are not perceived as bothersome. However, differentiation from unipolar depression has considerable practical importance. The following risk factors and predictors may assist differential diagnosis (recommendation grade: statement):

Positive family history of bipolar disorder

Severe melancholic or psychotic depression in childhood or adolescence

Rapid onset or swift regression of depression

Seasonal or atypical disease characteristics

Subsyndromal hypomanic symptoms in the course of depressive episodes

Development of (hypo)manic symptoms on exposure to antidepressants or psychostimulants.

Screening instruments for bipolar disorder over the course of the patient’s life to date (e.g., the Mood Disorders Questionnaire [5]) are advisable particularly in persons at high risk (such as patients with previous episodes of depression, suicide attempts, substance abuse, or temperamental anomalies). If screening yields a positive result, a psychiatrist should be brought in to ensure the diagnosis (recommendation grade: clinical consensus point [CCP]).

Valid diagnosis of a bipolar disorder requires careful exclusion of differential diagnoses (Table 3).

Table 3. Overview of differential diagnoses in bipolar disorder.

| Childhood and adolescence | Adulthood | |||||

| Young adulthood and middle age | Old age | |||||

| Psychiatric diseases | ||||||

| Affective disorders | Unipolar depression Repeated brief episodes of depression | |||||

| Dysthymia | ||||||

| Personality disorders | Borderline | Borderline | ||||

| Narcissistic | ||||||

| Antisocial | ||||||

| Other | ADHD | Schizophrenia | Early dementia | |||

| Schizophrenia | Schizoaffective episode | |||||

| Behavioral disturbances | ||||||

| Somatic diseases | ||||||

| General | Hypercortisolism | Thyroid diseases | ||||

| Neurological | Epilepsy | Epilepsy | ||||

| Encephalomyelitis | ||||||

| disseminata | ||||||

| Pick disease | ||||||

| Frontal cerebral tumors | ||||||

| Neurosyphilis | ||||||

| Pharmacological causes, substances | ||||||

| Antidepressants | Antidepressants | |||||

| Psychostimulants (e.g., cocaine, amphetamines, ecstasy) | Psychostimulants | |||||

| Antihypertensives (e.g., ACE inhibitors) | ||||||

| Antiparkinson drugs | ||||||

| Hormone preparations (e.g., cortisone, adrenocorticotrophic hormone [ACTH]) | ||||||

Bipolar disorders are very often accompanied by other psychiatric disorders. The most frequent of these are anxiety and compulsive disorders, substance abuse and dependence, impulse control disorders, eating disorders, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder /ADHD), and personality disorders (6).

Patients with bipolar disorder exhibit increased morbidity and mortality. Apart from suicide, this is predominantly attributable to cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes (7, 8). The somatic diseases with the greatest epidemiological significance are cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes mellitus, together with musculoskeletal disorders and migraine (9). Both psychiatric and somatic comorbidity should be carefully diagnosed at the outset and during the course of the bipolar disease, and the findings should be taken into account when deciding on treatment (recommendation grade: CCP).

The individual course of bipolar disorder should be documented, with particular reference to the attainment of defined treatment goals. This can be achieved with the assistance of established external evaluation instruments or by the patient keeping an ideally daily record of his/her moods (recommendation grade: CCP).

Treatment

The ultimate goal of treatment is to achieve as high as possible a level of psychosocial function and health-related quality of life.

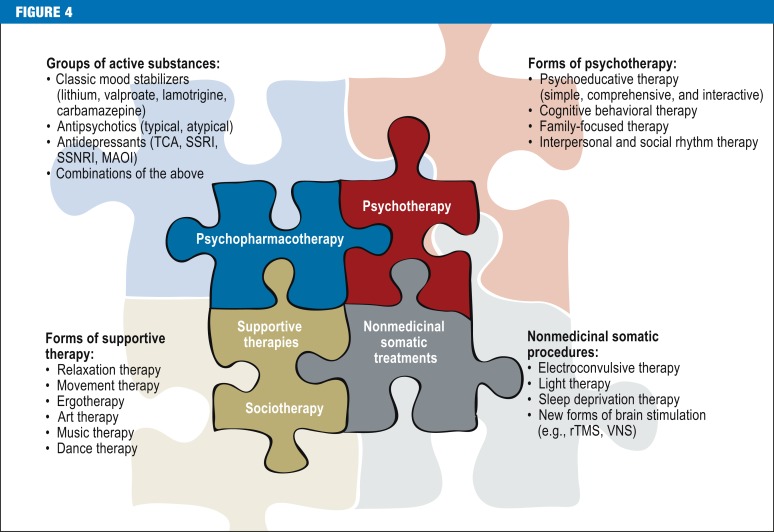

When planning the acute treatment of an episode of bipolar disease, the possible need to ward off recurrence must be borne in mind. Figure 4 provides an overview of the components of treatment.

Figure 4.

Possible components of treatment for bipolar disorder;

TCA, tricyclic antidepressants; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; SSNRI, selective serotonin and noradrenalin reuptake inhibitors; MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitors; rTMS, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation; VNS, vagus nerve stimulation

With regard to pharmacotherapy, details on mechanisms of action, indications, contraindications, dosing, interaction profiles, and potential short- and long-term adverse affects are given in the full version of the guideline. The recommendations in the full version always include reference to limitations on the use of a given substance, e.g., major adverse effects, interaction potential, or lack of official approval for the indication concerned. The pharmacotherapeutic combination treatments that are often used and even recommended in practice are unfortunately based on scant evidence.

A robust and enduring therapeutic relationship is important to the success of acute treatment and prevention (recommendation grade: statement). Simple psychoeducation should be the minimal aim of every medical, psychological, or psychosocial treatment (recommendation grade: statement). Supportive therapeutic measures (such as relaxation and movement therapy, ergotherapy, art therapy, and music/dance therapy) should form part of the individual integrated treatment plan (recommendation grade: CCP).

Treatment of mania

The foundation for the treatment of mania—before pharmacotherapy—is provided by the professional formation of a relationship and the creation of a therapeutically favorable environment. Pharmacotherapy then often has a central role, and the evidence is relatively extensive. Briefly, in the absence of contraindications the initial treatment should comprise monotherapy with one of the recommended mood stabilizers (lithium, carbamazepine, valproate), one of the recommended atypical antipsychotics (aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone), or haloperidol (in emergencies and for short-term treatment) (recommendation grade: B).

The effect sizes (numbers needed to treat, NNT) for lithium and the atypical agents for 3 weeks lay between 3 and 13 for a response greater than that found for placebo; the NNT for remission were comparable. Asenapine or paliperidone can also be used (recommendation grade: 0). Benzodiazepines can be added for a strictly limited period of time (recommendation grade: 0). In the event of inadequate response, combinations of mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics are recommended. Accompanying psychotherapy focuses on maintaining contact; behavioral-type interventions may be helpful in milder episodes (recommendation grade: 0).

In severe cases additional electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) can be carried out (recommendation grade: 0).

Treatment of bipolar depression

A problem in the treatment of bipolar depression is that in clinical practice, treatment strategies are often carried over from the extensive evidence for unipolar depression. Depression-specific pharmacotherapy is only exceptionally indicated in mild depressive episodes, which are usually handled with psychoeducation, psychotherapeutic interventions in the strict sense, advice on self-management, and self-help groups (recommendation grade: CCP). The dose and serum level of any existing preventive pharmacotherapy should be optimized. If such medication for long-term maintenance treatment is not yet in place but on consideration seems indicated, it should be initiated immediately, during the acute depressive episode (recommendation grade: CCP). Depression-specific pharmacotherapy is a strong option for the treatment of a moderately severe depressive episode (recommendation grade: statement). A severe episode should be treated pharmacotherapeutically (recommendation grade: CCP).

In summary, monotherapy with quetiapine should be started unless there are contraindications (recommendation grade: B). The NNT for 8 weeks lay between 5 and 7 for a response greater than that found for placebo; again, the NNT for remission were comparable. The mood stabilizers carbamazepine and lamotrigine, as well as olanzapine, can be prescribed, or alternatively selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) or bupropion (recommendation grade: 0). The patient should also receive psychotherapy (family-focused therapy [FFT], cognitive behavioral therapy [CBT], or interpersonal and social rhythm therapy [IPSRT] and/or sleep deprivation treatment (not in mixed episodes!) (recommendation grade: B); light therapy can also be offered (recommendation grade: 0).

During the first 4 weeks of pharmacological treatment, patient and physician should meet at least once a week so that risks and side effects can be recognized, the success of the treatment measures evaluated, and the cooperation between physician and patient improved. Thereafter, the period between appointments can be increased to 2–4 weeks; after 3 months it can perhaps be extended further (recommendation grade: CCP).

After 3 to 4 weeks the effect of the treatment should be carefully assessed. Depending on the result, the treatment strategy should be changed, adjusted, or left unaltered (recommendation grade: CCP).

ECT can be considered particularly in cases of treatment resistance and severe or even life-threatening situations.

Long-term maintenance treatment

Ideally, long-term maintenance treatment leads to complete freedom from depressive, manic, and mixed episodes, minimal if any interepisodic symptoms, and unimpaired enjoyment of life. In some cases, however, only secondary treatment goals are achieved (e.g., fewer, shorter, and/or less severe episodes or milder interepisodic symptoms). Partial successes may be overlooked because of the long duration of treatment. If the strategy for long-term maintenance treatment is completely unsuccessful, it will probably be decided to try a different approach; in the case of partial success, combination therapy incorporating the previous treatment is more likely (recommendation grade: statement). The disease course should be systematically documented. The best indicator of how long a maintenance treatment strategy should be pursued before deciding on its continuation or modification is the individual disease course. Clinical experience shows that the efficacy of a strategy can be assessed after a time corresponding to twice the patient’s average disease cycle. As a rule, a long-term maintenance treatment strategy should not be modified in the event of recurrence within 6 months of its commencement (recommendation grade: CCP).

Pharmacotherapy is usually an indispensable component of long-term maintenance treatment; in this regard, long clinical experience stands in contrast to considerable deficits in the scientific evidence. Single-agent maintenance treatment should be the goal. In brief, monotherapy with lithium is recommended in the absence of contraindications (recommendation grade: A). The NNT for 12 months was 14 for an additionally prevented episode compared to placebo, and for 24 months it was 3. If lithium is contraindicated, lamotrigine should be prescribed (recommendation grade: B). The mood stabilizers carbamazepine or valproate or the atypical antipsychotics aripiprazole, olanzapine, or risperidone can be recommended as well (recommendation grade: 0). It must be noted that—apart from lithium—the indication is restricted, e.g., to patients who tolerate the substance well in the acute phase and have responded adequately, or to prevention of only one pole of the disease.

In the case of inadequate response, compliance, dose, and serum level (if established) must be checked, and the dose or target serum level can be increased (if possible). If the response is still inadequate, pharmacological combination treatments are frequently used despite the paucity of evidence from controlled trials. In summary, combinations of a mood stabilizer and an atypical antipsychotic or combinations of two mood stabilizers can be given (recommendation grade: 0). The goal of the (accompanying) psychotherapy is to maintain the improvement or remission and prevent new episodes of illness. As a rule the treatment begins after resolution of an acute episode. Contact is initially weekly (two or more times a week in times of crisis), and treatment continues for several months or years. Extensive, interactive psychoeducation should be offered (recommendation grade: B); CBT, FFT, or IPSRT can also take place (recommendation grade: 0).

Clinical experience shows that creative and action-oriented measures (e.g., ergotherapy, art therapy, and music/dance therapy) contribute to the mental and social stabilization of bipolar patients. Relaxation techniques (e.g., progressive muscle relaxation) help patients to achieve stability by relieving specific symptoms (e.g., tension or sleep disorders). For none of these auxiliary forms of therapy, however, are there empirical studies of sufficient quality specifically focused on bipolar disorder.

Suicidality is common in bipolar disorder (the lifetime prevalence of suicide is 15%). For this reason, suicidal ideation and behavior must be clinically assessed at every patient contact; this may require precise, detailed questioning, and self-competence, social attachment, and earlier suicidality should be evaluated (recommendation grade: CCP). Suicidal patients require a greater commitment in terms of time and intensified therapeutic attachment (recommendation grade: CCP). In patients at risk of suicide, a robust therapeutic relationship may prevent suicide per se (recommendation grade: CCP). For long-term maintenance treatment in bipolar patients at risk of suicide, lithium should be considered for reduction of suicidal behavior (attempted suicide and suicide) (recommendation grade: A). Antidepressants (recommendation grade: B), antipsychotics, valproate, and lamotrigine are not suitable for acute treatment of the target syndrome suicidality. Psychotherapy focusing initially on suicidality should be considered.

For the treatment of specific groups of patients and advice on how to proceed in special situations, see (2) (in German). These specific treatment groups are:

Women of childbearing age, pregnant or breastfeeding women

Elderly patients

Patients with frequent psychiatric and/or somatic comorbidity

Treatment-resistant patients, including those with rapid cycling (a special form of the disease with at least four episodes of changing polarity within a 12-month period).

Trialogue, knowledge transfer, and self-help

The trialogue is particularly important for open, trusting, and successful cooperation between patients, family members, and mental health professionals (recommendation grade: statement). These three parties’ involvement in a participatory decision-making process should go beyond legally obligatory provision of information to include discussion of and joint decisions on treatment strategies, their desired effects, and the potential risks (recommendation grade: CCP).

Appropriate information transfer is known to have a positive influence on willingness to cooperate, adherence to treatment, self-confidence, and quality of life (recommendation grade: statement). Patients and their relatives should thus be informed about handbooks, self-help manuals, training programs (e.g., communication training, self-management training), advice in the literature, and any relevant upcoming events (recommendation grade: CCP) and encouraged to attend self-help groups. Direct integration of such groups into inpatient care or continuing cooperation with regional groups or contacts is advisable. This helps to stabilize the successful outcome of treatment (recommendation grade: CCP).

Patient care and the care system

The developers of the guideline take the view that improvements in the reality of patient care have great potential for bringing about a more favorable disease course and better psychosocial functionality. The parties with the most influence on the form that patient care takes are the patients themselves, their relatives, and the medical and nonmedical therapists and carers. In many regions primary care physicians are indispensable for the basic care of bipolar affective patients. Cooperation between primary care physicians and psychiatrists has proved valuable in rural areas (recommendation grade: CCP).

Despite methodological difficulties in the evaluation of evidence from complex health service research studies and in the transferability of data from other health care systems, there is broad agreement on how a good support system should look. Based on the findings of the studies by Simon et al. (11) and Bauer et al. (12, 13) and in view of the current health care system, access to and availability of the following is required (recommendation grade: statement):

Prompt qualified, disorder-specific psychiatric treatment

Psychoeducation and psychotherapy

Reliable help; if needed, by outreach programs

Crisis intervention treatment (inpatient ward or psychiatric day care unit)

Rehabilitation facilities with disorder-specific services

Disorder-specific self-help groups.

The goal must be to overcome the fragmented organization and financing of the psychiatric care system in Germany. Cross-sector care and financing models should be developed to cater for the needs of persons with severe psychiatric diseases, including bipolar affective patients (recommendation grade: CCP); see (2, 14).

Prospect

For the treatment of bipolar disorder, the existing evidence base requires consolidation through high-quality clinical studies on topics relevant to daily practice, e.g., treatment of bipolar depression, combination treatments, and specific health care strategies.

A follow-up survey of patients’ and relatives’ experience of care in Germany is planned, and comparison of the results with those of the first survey in 2010 (15) will reveal any differences following publication of the guideline. The full version of the guideline, complete with details such as discussion of its limitations, can be found (in German) at www.leitlinie-bipolar.de.

Supplementary Material

-

Project group

Prof. Michael Bauer (Project director)

Prof. Andrea Pfennig; M.Sc. (Project coordinator)

Prof. Peter Falkai (DGPPN, official representative: Prof. Oliver Gruber)

Dr. Johanna Sasse

Dr. Harald Scherk

Prof. Daniel Strech

Prof. Ina Kopp (AWMF)

Dr. Beate Weikert

Dipl.-Psych. Marie Henke

Dipl.-Psych. Maren Schmink

-

Steering group

Project group

Leaders of the working groups

Federal Organisation of (ex-)Users and Survivors of Psychiatry in Germany (BPE, Reinhard Gielen)

Bipolar Self-Help Network (BSNe, up to June 2009), DGBS Self-Help network (from July 2009) (Dietmar Geissler)

Federal Association of Relatives of the Mentally Ill (BApK, Karl Heinz Möhrmann)

DGBS Families Initiative (Horst Giesler)

AKdÄ (Drug Commission of the German Medical Association) (Dr. Tom Bschor)

BVDN (Professional League of German Neurologic Medicine) (Dr. Roland Urban)

BVDP (Professional Association of German Psychiatrists) (Dr. Lutz Bode)

Prof. Martin Härter (project group representative of the S3 Guideline Unipolar Depression)

-

Working groups

-

WG Trialogue, Knowledge Transfer, and Self-Help

Dietmar Geissler (patients’ representative)

Families’ representative (name on request)

Prof. Thomas Bock

Dipl. Psych. Maren Schmink

-

WG Diagnosis

Prof. Peter Bräunig (leader)

Dr. Katrin Rathgeber (deputy leader)

Dr. Katja Salkow

Dr. Emanuel Severus

Prof. Stephanie Krüger

Prof. Stephan Mühlig

Prof. Christoph Correll

Prof. Wolfgang Maier

Dr. Hans-Jörg Assion

Dr. Thomas Gratz

Dr. Rahul Sarkar

Patients’ representative (name on request)

Families’ representative (name on request)

-

WG Pharmacotherapy

Dr. Tom Bschor (joint leader)

Prof. Michael Bauer (joint leader)

Prof. Heinz Grunze

Dr. Harald Scherk

Dr. Beate Weikert

Dr. Johanna Sasse

Dr. Ute Lewitzka

Prof. Christopher Baethge

Dr. Günter Niklewski

Dr. Roland Urban

Patients’ representative (name on request)

Families’ representative (name on request)

-

WG Psychotherapy

Prof. Thomas D. Meyer (leader)

Prof. Martin Hautzinger (deputy leader)

Dr. Britta Bernhard

Prof. Thomas Bock

Dr. Jens Langosch

Prof. Michael Zaudig

Prof. Dr. Anna Auckenthaler

Dr. Karin Tritt

Dipl.-Psych. Marie Henke

Patients’ representative (name on request)

Families’ representative (name on request)

-

WG Nonmedicinal Somatic Procedures

Dr. Frank Padberg (joint leader)

Dr. T. Baghai (joint leader)

Dipl. Psych. Marie Henke (deputy leader)

Dr. Anke Gross

Dr. Christine Norra

Dr. Herbert Pfeiffer

Prof. Alexander Sartorius

Dr. Martin Walter

Patients’ representative (name on request)

Families’ representative (name on request)

-

WG Health Care System

Prof. Peter Brieger (joint leader)

Prof. Andrea Pfennig (joint leader)

Dr. Bernd Puschner

Dr. Hans-Joachim Kirschenbauer

Philipp Storz-Pfennig, MPH

Dr. Rita Bauer

Dr. Lutz Bode

Ivanka Neef/Antje Drenckhahn

Dr. Mazda Adli

Dipl.-Psych. Maren Schmink

Dr. Schützwohl

Dietmar Geissler

Families’ representative (name on request)

-

-

Consensus Conference

German Society for Bipolar Disorder (DGBS): Prof. Michael Bauer

German Association for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy (DGPPN): Prof. Peter Falkai, Prof. Oliver Gruber

Professional Association of German Psychiatrists (BVDP): Dr. Lutz Bode

Profe ssional League of German Neurologic Medicine (BVDN): Dr. Roland Urban

German Psychological Society (DGPs): Prof. Martin Hautzinger, Prof. Thomas D. Meyer

German Federal Conference of Psychiatric Hospital Directors (BDK): Prof. Lothar Adler, Dr. Harald Scherk

German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians (DEGAM): Dipl.-Soz. Martin Beyer

Working Group of Directors of Psychiatric Departments at General Hospitals in Germany (ACKPA): Dr. Günter Niklewski

Drug Commission of the German Medical Association (AKdÄ): Dr. Tom Bschor

DGBS Self-Help network: Dietmar Geissler

Federal Organisation of (ex-)Users and Survivors of Psychiatry in Germany (BPE): Reinhard Gielen

DGBS Families Initiative: Horst Giesler

Federal Association of Relatives of the Mentally Ill (BApK): Karl Heinz Möhrmann

Representative of WG Diagnosis: Prof. Peter Bräunig

Representative of WG Pharmacotherapy: Dr. Johanna Sasse

Representative of WG Psychotherapy: Prof. Thomas D. Meyer

Representatives of WG Nonmedicinal Somatic Procedures: Dr. Frank Padberg, Dr. Thomas Baghai

Representatives of WG Health Care System: Prof. Peter Brieger, Prof. Andrea Pfennig

-

Extended Review Group

-

Scientific medical societies:

German Medical Society of Behavioral Therapy (DÄVT)

German Society of Depth Psychology–Based Psychotherapy (DFT)

German Society of Geropsychiatry and Geropsychotherapy (DGGPP)

German Society for Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy (DGPM)

German Society for Psychoanalysis, Psychotherapy, Psychosomatic Medicine, and Depth Psychology (DGPT)

German Society for Rehabilitation Sciences (DGRW)

German Society for Behavioral Therapy (DGVT)

German Association for Social Psychiatry (DGSP)

German Psychoanalytical Society (DPG)

German Psychoanalytical Association (DPV)

German Professional Association for Behavioral Therapy (DVT)

German Society for Scientific Person-Centred Psychotherapy (GwG)

German Society of Suicide Prevention (DGS)

The German College for Psychosomatic Medicine (DKPM)

-

Occupational associations:

The Association of German Professional Psychologists (BDP)

Professional Association of Specialists in Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy in Germany (BPM)

German Federal Association of Contract Psychotherapists (BVVP)

German Association of Psychotherapists (DPTV)

German Working Group Self-help Groups (DAGSHG)

-

Other organizations:

Association of Leading Hospital-Based Psychiatrists and Psychosomatic Medicine Specialists

Nursing representative: National Association of Leading Psychiatric Nurses (BFLK)

Child and adolescent psychiatry representative:

German Society of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,

Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy (DGKJP)

German Professional Association for Art Therapy and Creative Therapy (DFKGT)

German Association of Occupational Therapists (DVE)

Depression Wards Working Group

Network “Aktion psychisch Kranke”

National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Funds

Private health insurance providers

German Statutory Pension Insurance Scheme

-

-

Expert Panel

Dr. Mazda Adli

Prof. Michael Bauer

Prof. Mathias Berger

Prof. Bernhard Borgetto

Prof. Peter Bräunig

Prof. Brieger

Dr. Tom Bschor

Dr. Christoph Correll

Prof. Peter Falkai

Prof. Wolfgang Gaebel

Prof. Waldemar Greil

Prof. Heinz Grunze

Prof. Fritz Hohagen

Prof. Georg Juckel

Prof. Stephanie Krüger

Prof. Wolfgang Maier

Prof. Andreas Marneros

Prof. Thomas D. Meyer

Prof. Hans-Jürgen Möller

Prof. Thomas Schläpfer

Prof. Hans-Ulrich Wittchen

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare.

Many different people devoted much energy to developing the S3 Guideline on Diagnosis and Treatment of Bipolar Disorder, most of them without payment.

Above all we are grateful to the boards and members of the DGBS and DGPPN, who not only financed the project with their membership dues and donations, but also supported it in many other ways. The project could not have been realized without them.

From the project team in Dresden, Beate Weikert, Maren Schmink, Marie Henke, Björn Jabs, and Steffi Pfeiffer deserve special thanks. The eSupplement lists the members of the individual guideline working groups who came together for a number of sessions and formed subcommittees to deal with particular topics; special thanks are due to the leaders of these working groups.

We are grateful to Prof. Ina Kopp and Dr. Cathleen Muche-Borowski for the support of the AWMF. The coordination teams of the S3 Guideline/National Disease Management Guideline Unipolar Depression (especially Prof. Martin Härter, Prof. Matthias Berger, and Dipl.-Psych. Christian Klesse) and the S3 Guideline Schizophrenia (especially Prof. Peter Falkai) accompanied our project from the outset and shared their expertise. We thank the scientific medical societies involved in the consensus conference for covering some of the travel costs.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors report the following relationships (in the past 5 years) in addition to connections with the societies or other organizations on whose behalf this article was written:

Prof. Pfennig has received financial support for scientific projects as well as speaking fees and/or travel costs for her own scientific activities from AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline.

Dr. Bschor has received speaking fees from Lilly, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Lundbeck, Servier, and AstraZeneca and congress travel support from Servier and AstraZeneca. He has received a payment from Sanofi-Aventis for writing a publication on a related topic. He has received reimbursement of attendance fees and travel and accommodation costs from AstraZeneca, as well as speaking fees from AstraZeneca, Lilly, BMS, Lundbeck, and Servier. He has received a payment from Sanofi-Aventis for carrying out commissioned clinical trials. He is a member of the board of the International Group for the Study of Lithium Treated Patients (IGSLI).

Prof. Falkai has received speaking fees or travel costs from the following pharmaceutical firms: AstraZeneca, Lundbeck, Janssen-Cilag, BMS, Essex, GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly, Lundbeck, and Pfizer. He has been a scientific advisory board member for AstraZeneca, Janssen-Cilag, Lilly, and Lundbeck, and has received financial support for a scientific project from AstraZeneca.

Prof. Bauer has received speaking fees from the following pharmaceutical firms: AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers-Squibb/Otsuka, Esparma, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen-Cilag, Lilly, Lundbeck, Pfizer, and Servier. He has been an advisory board member for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers-Squibb/Otsuka, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen-Cilag, Lilly, Lundbeck/Takeda, and Servier.

References

- 1.Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:543–552. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DGBS, DGPPN. S3-Leitlinie zur Diagnostik und Therapie Bipolarer Störungen. Langversion. 2012. www.leitlinie-bipolar.de.

- 3.Pfennig A, Weikert B, Falkai P, et al. Development of the evidence-based S3 guideline for diagnosis and therapy of bipolar disorders. Nervenarzt. 2008;79:500–504. doi: 10.1007/s00115-008-2455-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfennig A, Kopp I, Strech D, Bauer M. The concept of the development of S3 guidelines: additional benefit compared to traditional standards, problems and solutions. Nervenarzt. 2010;81:1079–1084. doi: 10.1007/s00115-010-3085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hautzinger M, Meyer TD. Diagnostik Affektiver Störungen. Hogrefe, Göttingen. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mantere O, Isometsa E, Ketokivi M, et al. A prospective latent analyses study of psychiatric comorbidity of DSM-IV bipolar I and II disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12:271–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newcomer JW. Medical risk in patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McIntyre RS, Konarski JZ, Misener VL, Kennedy SH. Bipolar disorder and diabetes mellitus: epidemiology, etiology, and treatment implications. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2005;17:83–93. doi: 10.1080/10401230590932380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McIntyre RS, Nguyen HT, Soczynska JK, Lourenco MT, Woldeyohannes HO, Konarski JZ. Medical and substance-related comorbidity in bipolar disorder: translational research and treatment opportunities. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2008;10:203–213. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.2/rsmcintyre. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gielen R, Geissler D, Giesler H, Bock T. Guideline on bipolar disorders and the importance of trialogue: chances and risks. Nervenarzt. 2012;83:587–594. doi: 10.1007/s00115-011-3416-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Bauer MS, Unutzer J, Operskalski B. Long-term effectiveness and cost of a systematic care program for bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:500–508. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bauer MS, McBride L, Williford WO, et al. Collaborative care for bipolar disorder: part I. Intervention and implementation in a randomized effectiveness trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:927–936. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.7.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bauer MS, McBride L, Williford WO, et al. Collaborative care for bipolar disorder: Part II. Impact on clinical outcome, function, and costs. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:937–945. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.7.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brieger P, Bode L, Urban R, Pfennig A. Psychiatric care for subjects with bipolar disorder: results of the new German S3 guidelines. Nervenarzt. 2012;83:595–603. doi: 10.1007/s00115-011-3417-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pfennig A, Jabs B, Pfeiffer S, Weikert B, Leopold K, Bauer M. Versorgungserfahrungen bipolarer Patienten in Deutschland: Befragung vor Einführung der S3-Leitlinie zur Diagnostik und Therapie bipolarer Störungen. Nervenheilkunde. 2011;30:333–340. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robert Koch-Institut. Bundesgesundheitssurvey. www.rki.de/DE/Content/Gesundheitsmonitoring/Studien/Degs/degs_node.html. 1998.

- 17.Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Jr., Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carney CP, Jones LE. Medical comorbidity in women and men with bipolar disorders: a population-based controlled study. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:684–691. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000237316.09601.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.AWMF, ÄZQ. Das deutsche Instrument zur methodischen Leitlinienbewertung. www.delbi.de. 2005.

- 20.NICE National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) 2006. Bipolar disorder: the management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and adolescents, in primary and secondary care. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keaney M, Lorimer AR. Auditing the implementation of SIGN (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network) clinical guidelines. Int J Health Care Qual Assur Inc Leadersh Health Serv. 1999;12:314–317. doi: 10.1108/09526869910297331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowe G, Twaddle S. The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN): an update. Scott Med J. 2005;50:51–52. doi: 10.1177/003693300505000202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328 doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

-

Project group

Prof. Michael Bauer (Project director)

Prof. Andrea Pfennig; M.Sc. (Project coordinator)

Prof. Peter Falkai (DGPPN, official representative: Prof. Oliver Gruber)

Dr. Johanna Sasse

Dr. Harald Scherk

Prof. Daniel Strech

Prof. Ina Kopp (AWMF)

Dr. Beate Weikert

Dipl.-Psych. Marie Henke

Dipl.-Psych. Maren Schmink

-

Steering group

Project group

Leaders of the working groups

Federal Organisation of (ex-)Users and Survivors of Psychiatry in Germany (BPE, Reinhard Gielen)

Bipolar Self-Help Network (BSNe, up to June 2009), DGBS Self-Help network (from July 2009) (Dietmar Geissler)

Federal Association of Relatives of the Mentally Ill (BApK, Karl Heinz Möhrmann)

DGBS Families Initiative (Horst Giesler)

AKdÄ (Drug Commission of the German Medical Association) (Dr. Tom Bschor)

BVDN (Professional League of German Neurologic Medicine) (Dr. Roland Urban)

BVDP (Professional Association of German Psychiatrists) (Dr. Lutz Bode)

Prof. Martin Härter (project group representative of the S3 Guideline Unipolar Depression)

-

Working groups

-

WG Trialogue, Knowledge Transfer, and Self-Help

Dietmar Geissler (patients’ representative)

Families’ representative (name on request)

Prof. Thomas Bock

Dipl. Psych. Maren Schmink

-

WG Diagnosis

Prof. Peter Bräunig (leader)

Dr. Katrin Rathgeber (deputy leader)

Dr. Katja Salkow

Dr. Emanuel Severus

Prof. Stephanie Krüger

Prof. Stephan Mühlig

Prof. Christoph Correll

Prof. Wolfgang Maier

Dr. Hans-Jörg Assion

Dr. Thomas Gratz

Dr. Rahul Sarkar

Patients’ representative (name on request)

Families’ representative (name on request)

-

WG Pharmacotherapy

Dr. Tom Bschor (joint leader)

Prof. Michael Bauer (joint leader)

Prof. Heinz Grunze

Dr. Harald Scherk

Dr. Beate Weikert

Dr. Johanna Sasse

Dr. Ute Lewitzka

Prof. Christopher Baethge

Dr. Günter Niklewski

Dr. Roland Urban

Patients’ representative (name on request)

Families’ representative (name on request)

-

WG Psychotherapy

Prof. Thomas D. Meyer (leader)

Prof. Martin Hautzinger (deputy leader)

Dr. Britta Bernhard

Prof. Thomas Bock

Dr. Jens Langosch

Prof. Michael Zaudig

Prof. Dr. Anna Auckenthaler

Dr. Karin Tritt

Dipl.-Psych. Marie Henke

Patients’ representative (name on request)

Families’ representative (name on request)

-

WG Nonmedicinal Somatic Procedures

Dr. Frank Padberg (joint leader)

Dr. T. Baghai (joint leader)

Dipl. Psych. Marie Henke (deputy leader)

Dr. Anke Gross

Dr. Christine Norra

Dr. Herbert Pfeiffer

Prof. Alexander Sartorius

Dr. Martin Walter

Patients’ representative (name on request)

Families’ representative (name on request)

-

WG Health Care System

Prof. Peter Brieger (joint leader)

Prof. Andrea Pfennig (joint leader)

Dr. Bernd Puschner

Dr. Hans-Joachim Kirschenbauer

Philipp Storz-Pfennig, MPH

Dr. Rita Bauer

Dr. Lutz Bode

Ivanka Neef/Antje Drenckhahn

Dr. Mazda Adli

Dipl.-Psych. Maren Schmink

Dr. Schützwohl

Dietmar Geissler

Families’ representative (name on request)

-

-

Consensus Conference

German Society for Bipolar Disorder (DGBS): Prof. Michael Bauer

German Association for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy (DGPPN): Prof. Peter Falkai, Prof. Oliver Gruber

Professional Association of German Psychiatrists (BVDP): Dr. Lutz Bode

Profe ssional League of German Neurologic Medicine (BVDN): Dr. Roland Urban

German Psychological Society (DGPs): Prof. Martin Hautzinger, Prof. Thomas D. Meyer

German Federal Conference of Psychiatric Hospital Directors (BDK): Prof. Lothar Adler, Dr. Harald Scherk

German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians (DEGAM): Dipl.-Soz. Martin Beyer

Working Group of Directors of Psychiatric Departments at General Hospitals in Germany (ACKPA): Dr. Günter Niklewski

Drug Commission of the German Medical Association (AKdÄ): Dr. Tom Bschor

DGBS Self-Help network: Dietmar Geissler

Federal Organisation of (ex-)Users and Survivors of Psychiatry in Germany (BPE): Reinhard Gielen

DGBS Families Initiative: Horst Giesler

Federal Association of Relatives of the Mentally Ill (BApK): Karl Heinz Möhrmann

Representative of WG Diagnosis: Prof. Peter Bräunig

Representative of WG Pharmacotherapy: Dr. Johanna Sasse

Representative of WG Psychotherapy: Prof. Thomas D. Meyer

Representatives of WG Nonmedicinal Somatic Procedures: Dr. Frank Padberg, Dr. Thomas Baghai

Representatives of WG Health Care System: Prof. Peter Brieger, Prof. Andrea Pfennig

-

Extended Review Group

-

Scientific medical societies:

German Medical Society of Behavioral Therapy (DÄVT)

German Society of Depth Psychology–Based Psychotherapy (DFT)

German Society of Geropsychiatry and Geropsychotherapy (DGGPP)

German Society for Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy (DGPM)

German Society for Psychoanalysis, Psychotherapy, Psychosomatic Medicine, and Depth Psychology (DGPT)

German Society for Rehabilitation Sciences (DGRW)

German Society for Behavioral Therapy (DGVT)

German Association for Social Psychiatry (DGSP)

German Psychoanalytical Society (DPG)

German Psychoanalytical Association (DPV)

German Professional Association for Behavioral Therapy (DVT)

German Society for Scientific Person-Centred Psychotherapy (GwG)

German Society of Suicide Prevention (DGS)

The German College for Psychosomatic Medicine (DKPM)

-

Occupational associations:

The Association of German Professional Psychologists (BDP)

Professional Association of Specialists in Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy in Germany (BPM)

German Federal Association of Contract Psychotherapists (BVVP)

German Association of Psychotherapists (DPTV)

German Working Group Self-help Groups (DAGSHG)

-

Other organizations:

Association of Leading Hospital-Based Psychiatrists and Psychosomatic Medicine Specialists

Nursing representative: National Association of Leading Psychiatric Nurses (BFLK)

Child and adolescent psychiatry representative:

German Society of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,

Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy (DGKJP)

German Professional Association for Art Therapy and Creative Therapy (DFKGT)

German Association of Occupational Therapists (DVE)

Depression Wards Working Group

Network “Aktion psychisch Kranke”

National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Funds

Private health insurance providers

German Statutory Pension Insurance Scheme

-

-

Expert Panel

Dr. Mazda Adli

Prof. Michael Bauer

Prof. Mathias Berger

Prof. Bernhard Borgetto

Prof. Peter Bräunig

Prof. Brieger

Dr. Tom Bschor

Dr. Christoph Correll

Prof. Peter Falkai

Prof. Wolfgang Gaebel

Prof. Waldemar Greil

Prof. Heinz Grunze

Prof. Fritz Hohagen

Prof. Georg Juckel

Prof. Stephanie Krüger

Prof. Wolfgang Maier

Prof. Andreas Marneros

Prof. Thomas D. Meyer

Prof. Hans-Jürgen Möller

Prof. Thomas Schläpfer

Prof. Hans-Ulrich Wittchen