“The revelation of wifely infidelity is a provocation so extreme that a “reasonable man” is apt to respond with lethal violence … So says the common law. Other spousal misbehavior – snoring or burning supper or mismanaging the family finances – cannot be invoked as provocation. Reasonable men do not react violently to their wives’ profligacy or stupidity or sloth or insults.”

(Daly and Wilson 1988:196)

1. Introduction

What causes marital conflict, and which marital conflicts are more likely to result in men’s violence against their wives? It has long been argued that men’s jealousy over women’s infidelity is the strongest impetus to men’s lethal and non-lethal violence against female partners. Less is known about the extent to which women’s jealousy over men’s infidelity precipitates men’s violence against female partners. Husbands are more likely than wives to commit infidelity, and men and women report a similar frequency and intensity of jealous emotions during recalls of potential infidelity. If men are likely to use time and resources for pursuit of extramarital sexual relationships, wives’ jealousy may play a critical role in mate retention, but at potential cost of instigating marital arguments and violence against wives. Given men’s greater size and strength, violence against wives may be used as a “bargaining” tool to strategically leverage a selfish outcome, despite potential costs to the victim, aggressor, and offspring.

This is the first study to document content and prevalence of marital arguments, and prevalence of men’s violence against wives during such arguments in a small-scale society, the Tsimane of Bolivia. We show that men’s diversion of resources from the family is a major source of arguments between spouses and husbands’ violence against their wives. We argue that husbands employ violence to limit wives’ mate retention effort and maintain men’s opportunities to pursue extramarital sexual relationships. We define violence against wives as any physical contact initiated by a husband with intent to harm a wife (hereafter termed wife abuse). The research design minimizes response and sampling bias in two ways: 1) data are obtained independently from both spouses instead of only one spouse, permitting assessment of spousal consistency in reporting; and 2) couples are sampled randomly rather than being self-selected for a high degree of marital conflict.

1.1 Male jealousy, marital conflict and wife abuse

Jealousy is experienced when a relationship is threatened, leading to responses reducing or eliminating the threat. The possibility of paternity uncertainty promotes the evolution of male jealousy. Jealous responses either deter same-sex competitors from mate theft, or deter mates from pursuing other sexual relationships. Wife abuse might be used as a “mate retention behavior”, functioning to maintain exclusive access to a mate and ensure that paternal investment is directed toward biological offspring. Risk of women’s infidelity, men’s jealousy, and wife abuse should therefore be linked.

Existing evidence supports these links. Two factors associated with risk of women’s infidelity are the woman’s mate value and the amount of time partners spend apart from each other. A woman’s mate value is the degree to which she enhances a man’s reproductive success, and is often proxied by her age or reproductive condition. Younger women are preferred partners across cultures and therefore likely have more extra-pair mating opportunities than their older counterparts. Younger women are more likely to conceive following sexual encounters, and have higher reproductive value (expected future fertility). This increases the cost to men of losing a young wife. Indeed, a wife’s young age is associated with an increase in her husband’s mate retention effort. Similarly, couples engage in aggressive interactions (verbal or physical) more frequently when a woman may be more likely to conceive.

Time partners spend apart from each other increases opportunities for surreptitious pursuit of extra-pair relationships. Time apart is associated with an increase in men’s mate retention effort. Degree of men’s mate retention effort increases with risk of female infidelity even after controlling for men’s dominant personality.

The male jealousy hypothesis therefore generates the following predictions; a husband’s jealousy over a wife’s suspected infidelity should be: 1) ranked highly as a common type of intense marital conflict, 2)a type of conflict frequently associated with wife abuse, 3)greater in marriages where a wife’s mate value, using her age as a proxy, is higher (i.e., when she is younger), and 4)greater in marriages where spouses spend more time apart. In addition, likelihood of wife abuse should be: 5)greater in marriages where a wife is younger, and 6)greater in marriages where spouses spend more time apart. A husband’s jealousy is operationalized dichotomously, as reporting an argument over a wife’s suspected infidelity in the past year. Spousal time apart is also operationalized dichotomously, as whether a husband participated in multi-day solitary wage labor in the past year.

1.2 Paternal disinvestment, marital conflict and wife abuse

Sex differences in potential reproductive rates affect optimal levels of reproductive effort. Whereas male reproductive effort is limited to courtship and copulation in most mammals and primates, humans have a history of high paternal investment. While nonhuman primate females increase work effort during pregnancy and lactation, thereby increasing maternal mortality, women decrease metabolism and store fat during pregnancy and decrease work effort during lactation. This suggests significant energetic support of reproduction by men. Throughout much of life Tsimane fathers produce more calories consumed by children per day than mothers and grandmothers combined; wives consume over 250 calories per day produced by husbands. Tsimane men thus clearly direct resources toward their nuclear families.

Unlike men women do not risk investing inadvertently in unrelated offspring. However, women do risk losing access to resources critical for reproduction if men divert resources to attract other women. Women experience jealousy as a response reducing or eliminating the threat of resource loss.

Paternal disinvestment is a construct representing men’s diversion of resources from the family for individual fitness gain. Men’s infidelity is an obvious indicator of paternal disinvestment because time and resources invested in gaining and maintaining access to extra-pair mates are unavailable for familial investment. Men’s infidelity is expected to result in women’s jealousy and women’s mate retention effort. Tsimane wives frequently complain to husbands about husbands’ suspected infidelity. Wives’ complaints to husbands are considered mate retention effort because complaints attempt to obstruct current and future male infidelity and resource diversions. The paternal disinvestment hypothesis proposes that wife abuse is employed by husbands to limit wives’ mate retention effort and maintain men’s opportunities to pursue extra-pair sexual relationships. Consistent with this logic, women’s physical aggression against mates precipitates most instances of partner violence against women. Men’s infidelity, women’s jealousy, women’s mate retention effort, and wife abuse should therefore be linked.

The paternal disinvestment hypothesis therefore generates the following predictions; a wife’s jealousy over a husband’s suspected infidelity should be: 1)ranked highly as a common type of intense marital conflict, 2) a type of conflict frequently associated with wife abuse, and 3) greater in marriages where a husband has an affair. In addition, likelihood of wife abuse should be: 4) greater in marriages where a husband has an affair. The positive association between men’s infidelity and rate of wife abuse should be mediated by marital arguments over wives’ jealousy. A wife’s jealousy is operationalized dichotomously, as reporting an argument over a husband’s suspected infidelity in the past year.

It is important to note that predictions 5 and 6 generated by the male jealousy hypothesis (section 1.1)do not follow exclusively from this hypothesis. If a husband’s infidelity is more likely when a wife is younger, then an inverse relationship between a wife’s age and rate of wife abuse is also consistent with the paternal disinvestment hypothesis. Similarly, if a husband’s infidelity is more likely when spouses spend more time apart, then a positive correlation between spousal time apart and rate of wife abuse is also consistent with the paternal disinvestment hypothesis. We address implications of these shared predictions in the Discussion.

2. Methods

2.1 Study population

Most Tsimane reside in 60+ villages in the Maniqui River basin in lowland Bolivia. Tsimane diet consists largely of plantains, rice, fish, meat, and fruit. Store-bought items include sugar, salt, cooking oil, kitchen utensils, medicine, and clothing. Such items are purchased with cash obtained through men’s itinerant wage labor with loggers, ranchers, or river merchants. Women rarely earn wages and money is rarely saved. While the vast majority of husbands’ wages are used for family purchases (Stieglitz, unpublished data), wives frequently complain to husbands about their excessive consumption of store-bought alcohol.

Despite a lack of patriarchal norms, low variance between sexes in resource holdings, and limited residential privacy (houses are closely spaced and most lack walls), Tsimane wife abuse is rife (Stieglitz et al. 2011). Common forms of wife abuse include shoving, kicking, and slapping, and reports of wives temporarily fleeing a home to avoid a husband’s imminent aggression are not unusual.

Tsimane marriages are stable despite the fact that many unions are arranged by kin. Demographic interviews of Tsimane ≥ age 45 reveal an average of 1.3 lifetime marital partners for both sexes (men: SD=0.66, Max=4, N=219; women: SD=0.64, Max=5, N=199). Polygyny is rare and usually sororal. There are norules of post-marital residence, but the norm is residence near the wife’s natal kin early in marriage.

2.2 Data collection

Data on marital arguments were collected by JS in one village in 2010 among monogamously married men and women from the same marriage. Male participants ranged in age from 19 to 53 (Mean±SD=37.1±10.19, N=21). Female participants ranged in age from 16 to 49 (Mean±SD=31.64±10.05, N=25). Husbands of four women were not present because of wage labor (all four men were under age 30 and married to younger women). To increase sample size for hypothesis tests in sections 3.3–3.5, we include pilot data collected by JS in 2007 among monogamously married men and women from two other villages. Sample sizes vary due to missing data and because not all follow-up questions were asked systematically during piloting. Participants from all three villages were familiar with JS because he resided in each village for several weeks or months prior to conducting interviews. Interviews were conducted privately to ensure confidentiality, and in the Tsimane language to increase informants’ comfort levels.

Participants were queried about most intense marital arguments in the past year, and in other years of the same marriage. We used a free-listing technique because it does not force respondents into selecting preconceived categories and allows for a more thorough account than otherwise possible. We focused on most intense arguments because we reasoned they would provide the most accurate recall. No restriction was placed on number of arguments one could mention. For each argument mentioned we asked identical structured questions of both sexes. We asked whether a wife experienced abuse during the argument, whether a husband had an affair in the preceding year, and whether a husband was involved in multi-day solitary wage labor in the preceding year. To categorize arguments we queried participants about other potential causes, ensuring that causes we identified were not germane. Participants were asked whether wife abuse occurred in the preceding year if either no arguments were reported that year or if wife abuse was not reported during an argument that year.

Demographic interviews used to assign ages and assess kinship were conducted by a Tsimane research assistant in one village from 2003–2004, and by JS and a senior graduate student in two villages from 2006–2007 (see [] for a description of methods). These data were updated during subsequent censuses.

JS obtained institutional (UNM) IRB approval and three-tiered informed consent from: 1) Tsimane government, 2) village leaders, and 3) interviewees.

2.3 Data analysis

Husbands’ and wives’ reports are analyzed separately to assess spousal consistency in reporting. Data on marital arguments (section 3.1) and prevalence of wife abuse during arguments (section 3.2) are segregated by year of occurrence (past year versus other years in marriage). This is done to determine if recently reported arguments are representative of all arguments. In addition to presenting aggregate-level data (i.e., reports from spouses from different marriages), we present couple-level data (i.e., reports from spouses from the same marriage) referencing the past year. Aggregate-level data can inflate degree of spousal consistency in reporting. For example, while aggregate husband-wife comparisons show similar rates of wife abuse, couple comparisons show that spouses disagree considerably on frequency and occurrence of men’s abusive tactics.

Binary logistic regression is used to model effects of covariates on three outcomes: likelihood of reporting in the past year: 1) an argument over a husband’s jealousy (section 3.3), 2) an argument over a wife’s jealousy (section 3.4), and 3) wife abuse (section 3.5). Results are presented as log-odds (B) and/or odds ratios (OR).

3. Results

3.1 Content and prevalence of marital arguments

Husbands’ reports

A wife’s jealousy is the most commonly reported type of argument (table 1). One-third of husbands reported this argument in the past year; over 80% (17/21 husbands) reported its occurrence in marriage. A wife’s complaints over a husband’s use of money is the second most commonly reported argument, and was prevalent in the past year. Other recurrent sources of conflict include a husband’s drinking and work effort. A husband’s jealousy was reported by nearly 20% of husbands (3/4 husbands reported multiple arguments over their own jealousy in the same year); but not one man reported this argument in the past year. Median number of years since this argument occurred is 20 (Mean ± SD=16±8). Of all arguments 58.2% refer directly to men’s diversion of resources from the family (summing arguments over a wife’s jealousy, husband’s use of money, and husband’s drinking in table 1). A husband’s jealousy accounts for only 6.1% of all arguments (table 1).

Table 1.

“What are the worst arguments with your spouse in the past year, and throughout your marriage in other years?” (free list; n=21 husbands, 25 wives)

| Husbands’ reports (n=115 arguments) | Wives’ reports (n=151 arguments) | Combined reports (n=266 arguments) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Past year (n=56) | Other years (n=59) | % totala (rank) | Past year (n=76) | Other years (n=75) | % total (rank) | Past year (n=132) | Other years (n=134) | % totala (rank) | |

|

| |||||||||

| Type of argument | # arguments (# men) | # arguments (# women) | # arguments (# individuals) | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Wife is jealous with husband | 12 (7) | 22 (16) | 29.6 (1) | 20 (10) | 28 (14) | 31.8 (1) | 32 (17) | 50 (30) | 30.8 (1) |

| Husband’s use of money | 16 (8) | 5 (5) | 18.2 (2) | 7 (5) | 2 (2) | 6.0 (5) | 23 (13) | 7 (7) | 11.3 (2) |

| Husband drinks too much | 6 (4) | 6 (3) | 10.4 (3) | 5 (4) | 1 (1) | 4.0 (8) | 11 (8) | 7 (4) | 6.8 (5) |

| Husband does not hunt/fish | 3 (3) | 6 (5) | 7.8 (4) | 9 (6) | 3 (3) | 7.9 (3) | 12 (9) | 9 (8) | 7.9 (4) |

| Husband does not work in field | 6 (5) | 3 (3) | 7.8 (4) | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 4.0 (8) | 9 (8) | 6 (6) | 5.6 (6) |

| Husband is jealous with wife | ----- | 7 (4) | 6.1 (6) | 5 (5) | 15 (8) | 13.2 (2) | 5 (5) | 22 (12) | 10.2 (3) |

| Wife does not care for joint child | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 5.2 (7) | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 5.3 (7) | 7 (6) | 7 (6) | 5.3 (7) |

| Wife lives far from natal kin | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 3.4 (8) | 3 (2) | 2 (2) | 3.3 (11) | 6 (4) | 3 (3) | 3.4 (10) |

| Wife visits natal kin too often | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 3.4 (8) | 1 (1) | ----- | 0.7 (16) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 1.9 (12) |

| Husband does not care for joint childb | ----- | 3 (2) | 2.6 (10) | 7 (5) | 3 (3) | 6.6 (4) | 7 (5) | 6 (5) | 4.9 (8) |

| Wife does not cook/wash clothes | 2 (2) | ----- | 1.7 (11) | 5 (4) | 4 (4) | 6.0 (5) | 7 (6) | 4 (4) | 4.1 (9) |

| Wife does not want to have sex | 2 (1) | ----- | 1.7 (11) | ----- | 3 (1) | 2.0 (13) | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 1.9 (12) |

| Husband is wage laboring too often | ----- | 1 (1) | 0.9 (13) | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | 1 (1) | 0.3 (17) |

| Wife does not work in field | 1 (1) | ----- | 0.9 (13) | 4 (4) | 2 (2) | 4.0 (8) | 5 (5) | 2 (2) | 2.6 (11) |

| Wife is “unattractive” or sterile | ----- | ----- | ----- | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 2.6 (12) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 1.5 (14) |

| Husband’s natal kin is “unkind” to wife | ----- | ----- | ----- | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1.3 (14) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.8 (15) |

| Husband visits others too often | ----- | ----- | ----- | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1.3 (14) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.8 (15) |

Total ≠ 100 due to rounding error

Includes complaints over a husband’s “neglect” that are unrelated to resource acquisition (e.g., involvement in reproductive decisions of adolescent children)

Wives’ reports

Wives also report their own jealousy as the most prevalent type of argument (table 1). In the past year 40% of wives reported this argument; 80% (20/25 wives) reported its occurrence in marriage. A husband’s jealousy is the second most commonly reported argument, with 20% of wives reporting its occurrence in the past year and 52% in marriage. Other recurrent sources of conflict include a husband’s work effort and use of money, and a wife’s work effort. Of all arguments 41.8% refer directly to men’s diversion of resources from the family. A husband’s jealousy accounts for only 13.2% of all arguments (table 1).

Couple-level data

Number of arguments reported by a husband and wife in the past year is strongly correlated (r=0.64, P=0.002, N=21 couples). But there are noteworthy reporting differences between spouses (table 2). While all wives reported at least one argument in the past year (Mean=2.9, Max=8), five husbands (24%) reported no arguments whatsoever (Mean=2.7, Max=9). Where husbands are more likely than wives to report arguments (column A>B in table 2), a wife’s behavior is more likely to be the cause. Where wives are more likely than husbands to report arguments (column B>A in table 2), a husband’s behavior (or that of his natal kin) is more likely to be the cause. Where spousal agreement exists (column E in table 2), arguments pertain to a husband’s use of money and drinking, a wife’s jealousy, and work effort of both spouses.

Table 2.

Spousal consistency in reporting marital arguments in the past year (n=21 couples)

| Type of argumenta | # couples in which argument reported by

|

(E=C/D) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | (B) | (C) | (D=A+B+C) | ||

| Husband onlyb | Wife onlyc | Both spousesd | Either spouse | Spousal agreemente | |

| Wife is jealous with husband | 5 | 5 | 2 | 12 | 0.17 |

| Husband’s use of money | 5 | 1 | 3 | 9 | 0.33 |

| Husband does not hunt/fish | 2 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 0.14 |

| Husband does not work in field | 4 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 0.14 |

| Husband drinks too much | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 0.33 |

| Wife does not care for joint child | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Husband does not care for joint child | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Wife does not cook/wash clothes | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0.25 |

| Wife does not work in field | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Husband is jealous with wife | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Wife lives far from natal kin | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Wife visits natal kin too often | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Wife does not want to have sex | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Husband’s natal kin is “unkind” to wife | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Husband visits others too often | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Wife is “unattractive” or sterile | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

An argument was not counted more than once, even if different occurrences of the same type of argument were reported by both spouses

Argument reported at least once by husband

Argument reported at least once by wife

Argument reported at least once by both spouses

Reflects extent of agreement among couples in which either spouse reported the argument (adapted from Szinovacz [1983])

3.2 Prevalence of wife abuse during marital arguments

Husbands’ reports

Wife abuse is most often associated with arguments over a wife’s jealousy (table 3). Nearly 40% of husbands reported wife abuse in marriage due to a wife’s jealousy. Almost 20% reported wife abuse in marriage due to an argument over a husband’s use of money. 14%of husbands reported wife abuse in marriage due to their own jealousy. Less frequently mentioned types of arguments associated with wife abuse include a husband’s drinking and wage labor involvement, work effort of both partners, and a wife’s frequent visitation of her natal kin. Of all abusive events 67.5% (n=25 events) occurred during arguments over men’s diversion of resources from the family (summing events during arguments over a wife’s jealousy, husband’s use of money, and husband’s drinking in table 3). A husband’s jealousy accounts for only 13.5% of abusive events (n=5, table 3).

Table 3.

Prevalence of wife abuse during marital arguments (n=21 husbands, 25 wives)

| Husbands’ reports (n=37 abusive events) | Wives’ reports (n=87 abusive events) | Combined reports (n=124 abusive events) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Past year (n=12) | Other years (n=25) | Total (% totala) | Past year (n=30) | Other years (n=57) | Total (% totala) | Past year (n=42) | Other years (n=82) | Total (% totala) | |

|

| |||||||||

| Type of argument precipitating wife abuse | # events (# men) | # events (# women) | # events (# individuals) | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Wife is jealous with husband | 5 (3) | 9 (7) | 14 (37.8) | 14 (6) | 26 (13) | 40 (46.0) | 19 (9) | 35 (20) | 54 (43.5) |

| Husband’s use of money | 5 (1) | 3 (3) | 8 (21.6) | 5 (3) | 1 (1) | 6 (6.9) | 10 (4) | 4 (4) | 14 (11.3) |

| Husband drinks too much | ----- | 3 (2) | 3 (8.1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2.3) | 1 (1) | 4 (3) | 5 (4.0) |

| Husband does not hunt/fish | ----- | 1 (1) | 1 (2.7) | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | 1 (1) | 1 (0.8) |

| Husband does not work in field | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (5.4) | ----- | 1 (1) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 3 (2.4) |

| Husband is jealous with wife | ----- | 5 (3) | 5 (13.5) | 2 (2) | 14 (7) | 16 (18.4) | 2 (2) | 19 (10) | 21 (16.9) |

| Wife does not care for joint child | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (5.4) | 1 (1) | 4 (3) | 5 (5.7) | 2 (2) | 5 (4) | 7 (5.6) |

| Wife lives far from natal kin | ----- | ----- | ----- | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 3 (3.4) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 3 (2.4) |

| Wife visits natal kin too often | ----- | 1 (1) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (1) | ----- | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1.6) |

| Husband does not care for joint child | ----- | ----- | ----- | 1 (1) | ----- | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1) | ----- | 1 (0.8) |

| Wife does not cook/wash clothes | ----- | ----- | ----- | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 5 (5.7) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 5 (4.0) |

| Wife does not want to have sex | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | 2 (1) | 2 (2.3) | ----- | 2 (1) | 2 (1.6) |

| Husband is wage laboring too often | ----- | 1 (1) | 1 (2.7) | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | 1 (1) | 1 (0.8) |

| Wife does not work in field | ----- | ----- | ----- | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2.3) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1.6) |

| Wife is “unattractive” or sterile | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | 3 (2) | 3 (3.4) | ----- | 3 (2) | 3 (2.4) |

Total ≠ 100 due to rounding error

Wives’ reports

Wives also report their own jealousy as most often associated with wife abuse(table 3). Over 70%reported wife abuse during this argument in marriage. While only two wives (8%) reported wife abuse due to a husband’s jealousy in the past year, 36% reported abuse during this argument in marriage. Less frequently mentioned types of arguments associated with wife abuse include a husband’s use of money, work effort of both partners, residence decisions, indicators of a wife’s mate value (physical appearance/fertility), frequency of sex in marriage, a husband’s drinking, and a wife’s frequent visitation of her natal kin. Of all abusive events 55.2% (n=48 events) occurred during arguments over men’s diversion of resources from the family. A husband’s jealousy accounts for only 18.4% of abusive events (n=16, table 3).

Couple-level data

Either spouse reported at least one abusive event in the past year in 6/21 couples (see table 4 for spousal consistency in reporting wife abuse by type of argument). Roughly 20% of husbands (4/21) and 25% of wives (5/21) reported wife abuse in the past year. Number of beatings reported by a husband and wife in the past year is strongly correlated (r=0.84, P=0.036, N=6 couples where either spouse reported violence). Husbands reported more beatings than wives in 2/6 couples; in both couples a husband had an affair in the past year and a wife’s jealousy was reported at least once by one or both spouses. Where wives are more likely than husbands to report wife abuse(column B>A in table 4), a husband’s behavior is more likely to be the cause. Where spousal agreement exists (column E in table 4), wife abuse is associated with a wife’s jealousy and a husband’s use of money.

Table 4.

Spousal consistency in reporting wife abuse in the past year (n=6 couples where either spouse reported wife abuse)

| Type of argument precipitating wife abusea | # couples where wife abuse reported by

|

(E=C/D) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | (B) | (C) | (D=A+B+C) | ||

| Husband onlyb | Wife onlyc | Both spousesd | Either spouse | Spousal agreement | |

| Wife is jealous with husband | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 0.5 |

| Husband’s use of money | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.5 |

| Husband does not work in field | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Husband drinks too much | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Wife does not care for joint child | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Husband does not care for joint child | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Wife does not cook/wash clothes | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Wife visits natal kin too often | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Violence was not counted more than once, even if reported by both spouses on different occasions during the same type of argument

Violence reported at least once by husband

Violence reported at least once by wife

Violence reported at least once by both spouses

3.3 Effect of wife’s age and spousal time apart on likelihood of reporting a husband’s jealousy

Husbands’ reports

A husband’s jealousy constituted only 6% of all arguments (table 1). Because not one man reported this argument in the past year, we are unable to test these predictions (but see wives’ reports). Examining the sample of arguments over a husband’s jealousy in other years of marriage, we find that age of the oldest wife in the year of the argument is 22. A husband was absent from the village due to wage labor in the year preceding each jealous argument.

Wives’ reports

Likelihood of reporting a husband’s jealousy in the past year is significantly lower among older women (B=−0.103, P=0.024, adjusted OR=0.903, controlling for spousal time apart, N=64). Likelihood of reporting a husband’s jealousy is marginally greater in marriages where spouses spend more time apart (B=1.943, P=0.084, husband absent=yes, adjusted OR=6.981, controlling for wife’s age). Inclusion of a wife’s age-by-husband absenteeism interaction term does not yield a significant parameter estimate. Residence near the husband’s natal kin does not affect likelihood of reporting a husband’s jealousy (not shown).

3.4 Effect of husbands’ infidelity on likelihood of reporting a wife’s jealousy

Husbands’ reports

Despite a small sample, likelihood of reporting a wife’s jealousy in the past year is marginally greater in marriages where a husband has an affair (B=1.833, P=0.074, husband had affair=yes, OR=6.25, N=21). Controlling for men’s affair status, men’s absenteeism does not affect likelihood of reporting a wife’s jealousy (nor is there a significant interaction effect of men’s affair status-by-men’s absenteeism).

Wives’ reports

Wives married to husbands that had affairs in the past year are significantly more likely to report being jealous with a husband (B=2.398, P=0.006, husband had affair=yes, OR=11.0, N=30). In separate models controlling for husbands’ infidelity in the past year, neither husband’s age, wife’s age, nor residential arrangement significantly affect likelihood of reporting a wife’s jealousy (not shown).

3.5 Effect of husbands’ infidelity, wife’s age, and spousal time apart on likelihood of wife abuse

Full models are shown in table 5. Husbands are less likely than wives to report wife abuse in the past year but the effect is not significant (B=−0.583, P=0.125, sex=male, OR=0.56, N=131). Because lower rates of wife abuse are associated with residence near the wife’s natal kin and presence of offspring, we control for both variables. Here neither variable significantly affects likelihood of wife abuse in the past year using either partner’s reports.

Table 5.

Multiple logistic regression of likelihood of wife abuse in the past year

| Parameter | Husbands’ reports (n=60) | Wives’ reports (n=71) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| B | SE | p | OR | B | SE | p | OR | |

| Husband had affair in past year=yes | 1.682 | 0.782 | 0.031 | 5.377 | 1.61 | 0.841 | 0.05 | 5.002 |

| Wife’s agea | −2.773 | 1.271 | 0.029 | 0.063 | −0.147 | 0.045 | 0.001 | 0.863 |

| Husband absent from village in past year=yes | 1.545 | 0.892 | 0.083 | 4.686 | 2.177 | 0.845 | 0.01 | 8.816 |

| Wife’s natal kin=resident in household cluster | −0.77 | 0.97 | 0.428 | 0.463 | 0.033 | 0.912 | 0.972 | 1.033 |

| Joint dependents < age 10=co-resident | −1.876 | 1.281 | 0.143 | 0.153 | −2.478 | 1.572 | 0.115 | 0.084 |

| Constant | 8.495 | 5.021 | 0.091 | 4.5 | 2.433 | 0.064 | ||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.445 | 0.63 | ||||||

Log of wife’s age was used to model husbands’ reports as it provided a better fit

Husbands’ reports

A husband’s infidelity is associated with a significantly greater likelihood of wife abuse in the past year controlling for other factors (table 5). Adjusted odds of wife abuse are over five times greater if a husband had an affair. The positive association between a husband’s infidelity and rate of wife abuse is mediated by a wife’s jealousy: male infidelity no longer predicts likelihood of wife abuse after including an “argument over female jealousy” parameter in the model, which is significant (B=3.628, P=0.045, wife’s jealousy reported in past year=yes, controlling for parameters in table 5, N=57). We are unable to test whether an “argument over male jealousy” parameter has an independent effect on rate of wife abuse after controlling for parameters in table 5 given the small sample of men’s reports of their own jealousy. Likelihood of wife abuse is greater among younger wives and where spouses spend more time apart (table 5, though effect of husbands’ absenteeism is marginally significant). Inclusion of a wife’s age-by-husband absenteeism interaction term does not yield a significant parameter estimate.

Wives’ reports

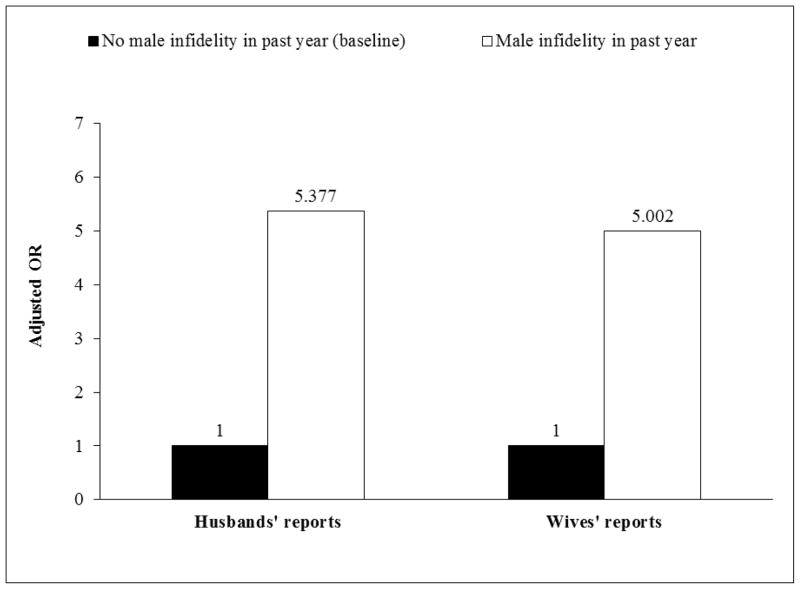

Consistent with husbands’ reports, adjusted odds of wife abuse are roughly five times greater if a husband had an affair (table 5, Pfigure 1). Also, male infidelity no longer predicts likelihood of wife abuse after including an “argument over female jealousy” parameter in the model, which is significant (B=10.864, =0.006, wife’s jealousy reported in past year=yes, controlling for parameters in table 5, N=68). Inclusion of an “argument over male jealousy” parameter in the model does not yield a significant parameter estimate after controlling for parameters in table 5 (not shown). Likelihood of wife abuse is greater among younger wives (table 5); rate of decline in wife abuse tracks age-related decline in both wives’ reproductive value and husbands’ infidelity (figure 2). Likelihood of wife abuse is also greater in marriages where spouses spend more time apart (table 5); adjusted odds of wife abuse are nearly nine times greater if a husband was absent from the village in the past year.

Figure 1.

Adjusted odds ratio (OR) for effect of male infidelity on likelihood of wife abuse in the past year (controls in table 5 set to sample means)

Figure 2.

Probability of wife abuse in the past year (wives’ reports) by wife’s age and reproductive value (Vx). Wives’ reports are used because this model explains a greater proportion of variance in likelihood of wife abuse(see NagelkerkeR2 in table 5). Also shown is the probability of a husband’s infidelity per year; estimates are derived using generalized estimating equations analysis on repeated measures over time (N=1,718 person-years in marriage representing 129 husbands, controlling for sex of respondent). Controls are set to sample means to derive all estimates; means of five-year age intervals are shown.

4. Discussion

Consistent with the paternal disinvestment hypothesis, a wife’s jealousy is the most frequent marital argument (table 1). Using a free-listing technique we find that roughly 80% of husbands and wives report marital conflict due to wives’ jealousy. Roughly 50% of all arguments refer directly to men’s diversion of resources from the family (summing arguments over a wife’s jealousy, husband’s use of money, and husband’s drinking using combined reports in table 1). Spouses agree that wife abuse is most often associated with arguments over a wife’s jealousy (tables 3 and 4). Roughly 60% of all abusive events occurred during arguments over men’s diversion of resources from the family (summing events during arguments over a wife’s jealousy, husband’s use of money, and husband’s drinking using combined reports in table 3).

Consistent with the male jealousy hypothesis, a husband’s jealousy is a frequently reported type of marital argument (table 1). This is despite the fact that response bias is evident from husbands’ reports of their own jealousy (tables 1 and 2). A husband’s jealousy accounts for 10% of all marital arguments (using combined reports from table 1). Spouses agree that wife abuse is frequently associated with arguments over a husband’s jealousy(table 3; but see table 4). Almost 20% of all abusive events occurred during arguments over a husband’s jealousy (using combined reports in table 3).

Likelihood of reporting a husband’s jealousy is greater in marriages involving younger wives. In addition, men’s jealousy is marginally greater in marriages where spouses spend more time apart. These findings are consistent with positive correlations between men’s mate retention effort and risk of women’s infidelity reported in Western and other non-Western settings.

Likelihood of reporting a wife’s jealousy is greater in marriages where a husband has an affair. This suggests that mate retention effort positively covaries with risk of partner infidelity, even in the absence of risk of cuckoldry. This underscores the importance of paternal investment, particularly because wives may realize that their mate retention effort increases risk of wife abuse.

Consistent with the paternal disinvestment hypothesis, likelihood of wife abuse is greater in marriages where a husband has an affair, even after controlling for a wife’s age, spousal time apart, and household demographic factors (table 5, figure 1). This effect, which is not predicted by the male jealousy hypothesis, is mediated by marital arguments over wives’ jealousy. Positive associations between male infidelity and rate of violence against female partners have been reported elsewhere based on aggregate-level data provided by either sex. We therefore propose that wife abuse is linked to the importance of paternal investment, and is a means by which husbands control wives’ responses to the male dual reproductive strategy of familial investment and pursuit of extramarital sexual relationships.

As predicted by the male jealousy hypothesis, likelihood of reporting wife abuse is greater in marriages involving younger wives (table 5, Pfigure 2). The inverse relationship between rate of wife abuse and a wife’s age is also consistent with the paternal disinvestment hypothesis. This is because Tsimane women’s jealousy is greater at younger ages, as men’s infidelity is most common during this time. Likelihood of reporting a wife’s jealousy in the past year is significantly lower among older women (B=−0.064, =0.013, adjusted OR=0.938, controlling for sex of informant, N=82). This effect is mediated by a husband’s infidelity (section 3.4).

The paternal disinvestment hypothesis therefore suggests a reexamination of the relationship between a wife’s age and rate of wife abuse. Numerous potential fitness benefits to women of engaging in extra-pair sex have been identified. Women’s infidelity might represent a response to men’s infidelity, to punish a partner and/or compensate for loss of male investment by having affairs with men offering resources. Is a husband’s infidelity associated with his wife’s infidelity? If so we might expect a higher prevalence of arguments over a wife’s suspected infidelity in marriages where either a husband has an affair, or where arguments occur over suspected male infidelity. Using combined reports, a husband’s jealousy was reported by 17 individuals at least once in a given year (N=20 person-years because three wives reported at least one such argument in multiple years). In 17/20 person-years where a husband’s jealousy was reported, a husband had an affair in the preceding year. Similarly, a husband’s jealousy was reported by either spouse at least once in 14 couples. At least one spouse in six of these couples (43%)also reported a wife’s jealousy at least once that year. These findings, while preliminary, suggest an association between a husband’s infidelity and his wife’s infidelity that requires further testing. They are consistent with two related findings reported by Greiling and Buss (2000): 1) an important perceived benefit to women of extra-pair sex is to gain revenge against a partner following his infidelity; and 2) women rank discovery of their partner’s infidelity as the context most likely to result in their own infidelity.

One hypothesis is that promiscuous men are more likely paired with promiscuous women, and increase mate retention effort as a result. This might explain why we and other researchers find positive correlations between men’s mate retention effort and indicators of women’s infidelity. While this finding is consistent with the hypothesis that men’s mate retention effort minimizes risk of cuckoldry, it is also some what counterintuitive. All else equal one might expect men actively engaging in mate retention tactics to be more effective at restricting women’s infidelity.

The extent to which wife abuse is used to punish past and/or prevent future female infidelity is unclear. If women’s infidelity is indeed a response to men’s infidelity, given that rate of Tsimane men’s infidelity peaks at younger ages (figure 2), one might expect women’s infidelity to peak at younger ages as well. Since rate of wife abuse is highest at younger ages (table 5 and figure 2), violence may be used by husbands to both prevent future cuckoldry and punish women’s infidelity at its peak. This logic is consistent with both male jealousy and paternal disinvestment hypotheses. If supported cross-culturally, it suggests that an expanded framework incorporating men’s infidelity explains more variance in rate of wife abuse than traditional frameworks only emphasizing women’s mate value. The negative relationship between women’s age and rate of violence against women that is predicted by the male jealousy hypothesis is not always found.

Likelihood of reporting wife abuse is greater in marriages where spouses spend more time apart. This finding is consistent with data from Western samples showing a positive relationship between time apart and male mate retention effort. Although time apart can increase risk of female infidelity and male jealousy as predicted by the male jealousy hypothesis, this hypothesis also predicts that husbands with younger wives should maintain close partner proximity. Yet Tsimane men’s absenteeism due to wage labor peaks early in marriage, when wives are younger. Many young Tsimane men who have worked with us over the years have voiced concerns over their wives’ fidelity during long stints away from home. So why do young Tsimane men engage in long-term solitary wage labor if by doing so they increase their risk of cuckoldry?

One hypothesis is that wage earnings, while often used to make family purchases, are also used by husbands to pursue affairs. This hypothesis is consistent with our finding that a common source of marital arguments and wife abuse according to both spouses is a husband’s use of money (tables 1–4). It is also consistent with our finding that men’s absenteeism due to wage labor positively covaries with likelihood of their own infidelity, controlling for other factors (Stieglitz, unpublished data). Furthermore, husbands’ self-reports of daily wages and wives’ estimates of their husbands’ wages are not strongly correlated: husbands report a wage that is 8% higher than what their wives report. Mating effort might therefore partially motivate Tsimane men’s wage labor, despite the fact that men’s absenteeism increases their risk of cuckoldry. From this perspective the positive relationship between men’s absenteeism and rate of wife abuse(table 5) is consistent with the paternal disinvestment hypothesis. Taken together, these findings highlight that within marriage pursuit of divergent mating strategies might result in deception over resource production and distribution; such deception increases risk of verbal and physical aggression between partners.

4.1 Limitations

Causation cannot be inferred, so men’s absenteeism due to wage labor or men’s infidelity might be an outcome of wife abuse. Disinvesting men might also be more likely to select partners tolerating wife abuse, or might have more abusive personalities. Even if paternal disinvestment causes wife abuse, the effect might not be direct. For example, wives might punish disinvesting husbands by having affairs, which might result in men’s jealousy and wife abuse. Or wives might punish disinvesting husbands by withdrawing their own parental investment, which might result in husbands’ attempts to maintain maternal investment using wife abuse. These hypotheses require further testing. Because we lack ordinal measures of men’s infidelity (e.g., one-time sexual encounter compared to repeated encounters with the same individual), we are unable to test whether extent of men’s affair involvement positively covaries with rate of wife abuse. Finally, sample size is small, we only focus on physical wife abuse, and interview data can produce socially desirable responses. But it is noteworthy that most results are robust across sexes.

4.2 Conclusion

Men’s diversion of resources from the family is a salient driver of marital conflict and wife abuse using Tsimane husbands’ and wives’ reports of their own marriages. While we find strong support for both male jealousy and paternal disinvestment hypotheses, it is men’s infidelity, not women’s, that precipitates most instances of marital conflict and wife abuse. Men’s aggression towards their wives therefore facilitates diversion of family resources for men’s selfish interests. An evolutionary framework emphasizing consequences of infidelity by both partners helps integrate existing findings and offers novel research directions.

Acknowledgments

We thank study participants for sharing personal stories. We thank Martie Haselton, Chris von Rueden, and two anonymous reviewers for helpful feedback. Funding was provided by National Science Foundation (NSF) Dissertation Improvement Grant to JS (BCS-0721237), an NSF grant to MG and HK (BCS-0136274, BCS-0422690), and a National Institute on Aging grant to HK and MG (1R01AG024119).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

JONATHAN STIEGLITZ, Department of Anthropology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131.

MICHAEL GURVEN, Department of Anthropology, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106.

HILLARD KAPLAN, Department of Anthropology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131.

JEFFREY WINKING, Department of Anthropology, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843.

References

- Alio AP, Nana PN, Salihu HM. Spousal violence and potentially preventable single and recurrent spontaneous fetal loss in an African setting: cross-sectional study. The Lancet. 2009;373(9660):318–324. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altmann J. Baboon Mothers and Infants. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins D, Jacobson N, Baucom D. Understanding infidelity: correlates in a national random sample. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:735–749. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.4.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker R, Bellis M. Human sperm competition. London: Chapman & Hall; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Borgerhoff Mulder M. Kipigis bride wealth payments. In: Betzig L, Borgerhoff Mulder M, Turke P, editors. Human reproductive behavior. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Buss D. From vigilance to violence: Tactics of mate retention in American undergraduates. Ethology and Sociobiology. 1988;9:291–317. [Google Scholar]

- Buss D. Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1989;12:1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Buss D. The dangerous passion. New York: The Free Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Buss D, Shackelford T. From vigilance to violence: Mate retention tactics in married couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72:346–361. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.2.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clutton-Brock T. The Evolution of Parental Care. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Daly M, Wilson M. Homicide. New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Daly M, Wilson M, Weghorst SJ. Male sexual jealousy. Ethology and Sociobiology. 1982;3(1):11–27. [Google Scholar]

- Djikanovic B, Jansen HAFM, Otasevic S. Factors associated with intimate partner violence against women in Serbia: a cross-sectional study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;64:728–735. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.090415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dude A. Spousal intimate partner violence is associated with HIV and other STIs among married Rwandan women. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;15:142–152. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9526-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Nduna M, Levin J, Jama N, Khuzwayo N, Koss MP, Duvvury N. Perpetration of partner violence and HIV risk behaviour among young men in the rural Eastern Cape, South Africa. AIDS. 2006;20(16):2107–2114. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000247582.00826.52. 2110.1097/2101.aids.0000247582.0000200826.0000247552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueredo A, Corral-Verdugo V, Frías-Armenta M, Bachar K, White J, McNeill P, Kirsner B, Castell-Ruiz I. Blood, solidarity, status, and honor: The sexual balance of power and spousal abuse in Sonora, Mexico. Evolution and Human Behavior. 2001;22:295–328. [Google Scholar]

- Flinn M. Mate guarding in a Caribbean village. Ethology and Sociobiology. 1988;9:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Goetz A. Violence and abuse in families: The consequences of paternal uncertainty. In: Salmon C, Shackelford T, editors. Family Relationships: An Evolutionary Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 259–274. [Google Scholar]

- Goetz A, Shackelford T. Sexual coercion and forced in-pair copulation as sperm competition tactics in humans. Human Nature. 2006;17(3):265–282. doi: 10.1007/s12110-006-1009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz A, Shackelford T. Sexual coercion in intimate relationships: A comparative analysis of the effects of women’s infidelity and men’s dominance and control. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2009;38(2):226–234. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9353-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray P, Anderson K. Fatherhood: Evolution and human paternal behavior. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Greiling H, Buss D. Women’s sexual strategies: the hidden dimension of extra-pair mating. Personality and Individual Differences. 2000;28:929–963. [Google Scholar]

- Haselton M, Buss D, Oubaid V, Angleitner A. Sex, Lies, and Strategic Interference: The Psychology of Deception Between the Sexes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31(1):3–23. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander D. Traditional Gender Roles and Intimate Partner Violence Linked in China. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2005;31:46–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado A, Hill K, Kaplan H, Hurtado I. Trade-offs between female food acquisition and child care among Hiwi and Ache foragers. Human Nature. 1992;3:185–216. doi: 10.1007/BF02692239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaighobadi F, Starratt V, Shackelford T, Popp D. Male mate retention mediates the relationship between female sexual infidelity and female-directed violence. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008;44:1422–1431. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan H, Gurven M, Winking J, Hooper P, Stieglitz J. Learning, menopause, and the human adaptive complex. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1204:30–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig M, Stephenson R, Ahmed S, Jejeebhoy S, Campbell J. Individual and Contextual Determinants of Domestic Violence in North India. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:132–138. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.050872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey LA, Williams C, Larsen U. Gender Inequality and Intimate Partner Violence among Women in Moshi, Tanzania. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2005;31(3):124–130. doi: 10.1363/3112405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary S, Slep A. Precipitants of Partner Aggression. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20(2):344–347. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice A, Goldberg G. Energy adaptations in human pregnancy: Limits and long-term consequences. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2000;71 (suppl):1226–1232. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.5.1226s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutzwohl A, Koch S. Sex differences in jealousy: The recall of cues to sexual and emotional infidelity in personally more and less threatening context conditions. Evolution and Human Behavior. 2004;25:249–257. [Google Scholar]

- Shackelford T, Goetz A, McKibbin W, Starratt V. Absence makes the adaptations grow fonder: Proportion of time apart from partner, male sexual psychology, and sperm competition in humans (Homo sapiens) Journal of Comparative Psychology. 2007;121(2):214–220. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.121.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackelford T, LeBlanc G, Drass E. Emotional reactions to infidelity. Cognition and Emotion. 2000;14:643–659. [Google Scholar]

- Starratt V, Shackelford T, Goetz A, McKibbin W. Male mate retention behaviors vary with risk of partner infidelity and sperm competition. Acta Psychologica Sinica. 2007;39(3):523–527. [Google Scholar]

- Stieglitz J, Kaplan H, Gurven M, Winking J, Vie Tayo B. Spousal violence and paternal disinvestment among Tsimane’ forager-horticulturalists. American Journal of Human Biology. 2011;23:445–457. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.21149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symons D. The Evolution of Human Sexuality. New York: Oxford University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Szinovacz M, Egley L. Comparing one-partner and couple data on sensitive marital behaviors: The case of marital violence. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1995;57(4):995–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Szinovacz ME. Using Couple Data as a Methodological Tool: The Case of Marital Violence. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1983;45(3):633–644. [Google Scholar]

- Trivers R. Parental investment and sexual selection. In: Campbell B, editor. Sexual Selection and the Descent of Man, 1871–1971. Chicago: Aldine; 1972. pp. 136–179. [Google Scholar]

- Winking J, Kaplan H, Gurven M, Rucas S. Why do men marry and why do they stray? Proceedings of the Royal Society Series B. 2007;274:1643–1649. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.0437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]