Abstract

Enzyme activated prodrugs have been investigated and sought after as highly specific, low side effect treatments, especially for cancer therapy. Unfortunately, excellent targets for enzyme activated therapy are rare. Here we demonstrate a system based on cell delivery that can carry both a prodrug and an activating enzyme to the cancer site. Raw264.7 cells (mouse monocyte/macrophage like cells, Mo/Ma) were engineered to express intracellular rabbit carboxylesterase (InCE), which is a potent activator of the prodrug irinotecan to SN38. InCE expression was regulated by the TetOn® system, which silences the gene unless a tetracycline, such as doxycycline, is present. Concurrently, an irinotecan-like prodrug, conjugated to dextran, was synthesized that could be loaded into the cytoplasm of Mo/Ma. To test the system, a murine pancreatic cancer model was generated by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of Pan02 cells. Engineered Mo/Ma were loaded with the prodrug and were injected i.p. Two days later, doxycycline was given i.p. to activate InCE, which activated the prodrug. A survival study demonstrated that this system significantly increased survival in a murine pancreatic cancer model. Thus, for the first time, a prodrug/activating enzyme system self-contained within tumor-homing cells has been demonstrated that can prolong the life of i.p. pancreatic tumor bearing mice.

Keywords: Prodrug Therapy, Cytotherapy, Pancreatic Cancer, Cancer Targeting

1. Introduction

Targeting cancer therapy specifically to the cancer site so that it does not affect healthy tissue is a major objective of current cancer research.[1] Many different strategies for targeting therapy have been developed, including targeted drug delivery vehicles,[2,3] antibody targeted therapy,[4] protease targeted therapy,[5,6] and others. Recently, a new strategy known as gene-directed enzyme/prodrug therapy (GDEPT) has been used with varying levels of success. This strategy uses a vector targeted gene for an enzyme that will convert a relatively inactive prodrug to its active drug counterpart.[7-10] Two steps are needed for this to happen. First, the enzyme must be targeted to or produced by the tumor. The prodrug then needs to be delivered to the tumor for activation. Another recent method for targeting cancer therapy is using targeted cytotherapy. Cytotherapy utilizes delivery cells, such as stem cells or other cells, to carry a payload to the tumor site.[11-18] Here we propose to combine both steps of GDEPT with cytotherapy to create a single cell-based therapy system.

Irinotecan (CPT-11) is a prodrug that is converted by carboxylesterase (CE) to SN38, a potent topoisomerase I inhibitor. CPT-11 is a clinically used cancer therapy and is approved for colorectal carcinoma therapy.[19-21] Unfortunately, the use of CPT-11 is limited because only 2-5% of the injected dose is converted to active SN38, and prodrug administration has high incidences of undesirable side effects such as diarrhea and neutropenia.[20,22] These side effects are, in large part, caused by further metabolism (glucuronidation) of SN38 by UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1.[23] SN38 also has poor solubility in water, which further limits the effectiveness of CPT-11.[20,22]

Rabbit liver CE activates CPT-11 to SN38 much more efficiently than human-derived CE.[24] Rabbit liver CE secreted by neural stem cells has been shown to be effective after systemic administration of irinotecan in several preclinical models.[24-26] Unfortunately, treating humans with rabbit CE could induce immune responses that would nullify the utility of treatment and perhaps cause unwanted side effects.[27] Containment of both the prodrug and the enzyme activator in a single delivery device could reduce potential immune responses and sequester the prodrug from the body. If the delivery device could target the cancer site and delay activation of the prodrug until arrival at the cancer site, unwanted side effects could be reduced.

Monocytes and macrophages are known to infiltrate tumor sites and thus could act as drug delivery vehicles to tumors. Several recent studies have demonstrated the feasibility of delivering therapy to tumors using monocytes or macrophages, including targeting liposome-contained fluorescent markers to gastric tumors,[28] targeting adenovirus to prostate tumors,[29] and targeting gold nanoshells to gliomas.[30]

We hypothesized that using a bioengineered, tumor-homing, cell delivery mechanism could act as such a system. Therefore, using the TetOn® system, Raw264.7 cells (monocyte/macrophage-like cells, Mo/Ma) were stably engineered to produce intracellular rabbit CE (InCE) in a regulated fashion so that they only produce InCE in response to a tetracycline; these cells are hereafter referred to as DS (double stable) monocyte-like cells. In order to load the prodrug into the cells effectively, an SN38-dextran prodrug was synthesized, which should have better cellular uptake and retention because of the dextran base. The TetOn® InCE monocyte-like cells were loaded with this SN38-dextran prodrug and injected i.p. into a murine pancreatic cancer model. Two days later, doxycycline was given i.p. to induce InCE expression and activate the SN38. Here we demonstrate that this system significantly increased the survival time of mice bearing i.p. pancreatic tumors.

2. Results

2.1. Synthesis of SN38-Dextran

Synthesis of the SN38-dextran prodrug produced an off-white powder that was not soluble in water, but could be stably suspended in water. NMR spectra confirmed successful synthesis of both the succinic acid-modified dextran and the SN38-dextran (Supplementary Figures 1 and 2). Assaying for the amount of SN38 incorporated into the dextran indicated that there were approximately 24 SN38 residues per 70 kDa dextran molecule, which translates to approximately 1 SN38 for every 18 glucose residues (standard curve in Supplementary Figure 3).

2.2. Toxicity and Loading of SN38-Dextran

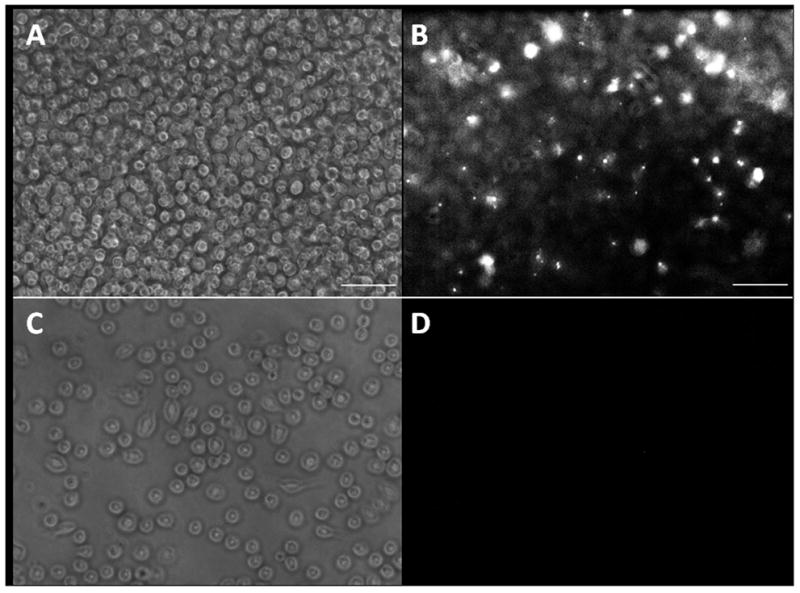

To determine the correct concentration of SN38-dextran to load onto the DS monocyte-like cells, DS monocyte-like cells were loaded overnight using 0 to 500 μg/mL SN38-dextran in the medium. After washing, cells were viewed with a Zeiss Axiovert epifluorescence microscope using the DAPI filter (Figure 1). SN38 fluorescence was visible down to loading concentrations of 5 μg/mL. Nearly all cells had some SN38 content, although loading was not consistent across all cells, with a small subset of cells taking up substantially more SN38. These cells seemed to be uniformly distributed throughout the population.

Figure 1. SN38 loading of monocyte-like cells.

A+B. Monocyte-like cells were incubated overnight with 10 mg/mL of SN38-dextran. The medium was then removed and cells were washed with PBS and fresh medium was added. A. bright field and B. fluorescence with DAPI filter were taken at 20X magnification. C+D. Control monocyte-like cells were incubated without dextran overnight. The medium was then removed and cess were washed with PBS and fresh medium was added. C. bright field and D. fluorescence with DAPI filter were taken at 20X magnification. Scale bars are 100 mm.

The toxicity of the SN38-dextran was measured from 0 to 500 μg/mL. For loading concentrations of 50 μg/mL or above, nearly 100% cell death was evident in the light microscope, so further measurement was not done on these concentrations. For concentrations at or below 25 μg/mL, an MTT assay was run to determine cell viability (Figure 2). Concentrations below 5 μg/mL were not substantially toxic to the cells. At 10 μg/mL, there were approximately 30% fewer live cells according to the MTT assay, and at 25 μg/mL there were 80% fewer live cells. In order to maximize loading and minimize loss of cells during the loading process, 10 μg/mL SN38-dextran was chosen for loading the DS monocyte-like cells for the in vivo experiments.

Figure 2. Toxicity of SN38-dextran prodrug.

Cells were incubated overnight at varying concentrations of SN38-dextran. In the morning the medium was removed, the cells were washed in PBS, and fresh medium was added. An MTT assay was then run to determine cell viability.

To determine the concentration of SN38 actually loaded into the cells for the in vivo experiment, cell lysates were prepared as discussed in Methods. Measuring the amount of SN38 per cell in the lysates indicated that there were approximately 5.12×10-18 mols of SN38 per cell, or 10.24 pmols (4 ng) of SN38 per 2,000,000 cell injection. This corresponds to a loading efficiency of 0.68%, which, compared to the calculated volume of monocytes in the flask (0.2% vol/vol) is more than a three-fold concentration of the SN38-dextran in the cells, indicating active uptake.

2.3. Tracking of Monocyte-like Cells to Pancreatic Tumors

To determine if monocyte-like cells would home to Pan02 tumors, two mice bearing i.p. Pan02 tumors were injected i.p. with labeled monocyte-like cells. Three days after injection, the first mouse was euthanized. Tissue imaging showed that the monocyte-like cells effectively homed to the tumor (Figure 3), but did not infiltrate other organs, including the pancreas, spleen, liver, and kidney. At six days, the second mouse was sacrificed and tissue imaging showed again that the monocyte-like cells penetrated tumor tissue but not healthy tissue (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Monocyte-like cells home to tumor tissue but not healthy tissue.

Monocyte-like cells, treated with PKH26 were injected i.p. to Pan02 tumor bearing mice. A: dark field fluorescence from pancreatic tumor tissue three days after monocyte-like cells injection, magnification 10x. B: H&E staining of serial sections of the tissue above. C-F: dark field fluorescence from healthy tissue three days after monocyte-like cell injection, magnification 20x, C. Lung; D. Pancreas; E. Kidney; F. Liver. Blue is DAPI nuclear staining and orange is PKH26 fluorescence (monocyte-like cells). All scale bars are 100 mm.

2.4. Mouse Duration to Clinical Signs (‘Survival’)

To determine the effectiveness of the treatment, Pan02 tumors were given i.p. to C57BL/6 mice and the mice were treated as described in Methods. The euthanasia data were collected and modeled using Kaplan-Meier survival statistics. The data are reported as days subsequent to tumor injection (day 0) (Figure 4). The chi-squared log-rank test showed that the survival curves were significantly different (p=0.0002), indicating that at least one of the survival curves is significantly different than the rest. All of the mice from the tumor control group had been euthanized due to clinical signs of cancer (hereafter referred to as ‘succumbed’) by day 23. Similarly the monocyte-like cells control mice all succumbed by day 25, and all of the SN38 control mice succumbed by day 22. Modeling with Kaplan-Meier survival statistics showed no significant difference between any of these groups. The doxycycline control mice showed slightly longer survival times with mice lasting until day 26.5. This duration to clinical signs or ‘survival’ curve was shown to be significant (p=0.0095) against the tumor control group and not significant (p=0.0840) against the monocyte-like cells control group. The SN38 treatment mice survived substantially longer, with mice lasting until 29 days. The survival of the SN38 treatment group was shown to be significant against all control groups (p=0.0270 against doxycycline control, p=0.0018 against SN38 control, p=0.0025 against monocyte-like cells control, and p=0.0010 against tumor control).

Figure 4. Duration to clinical symptoms (survival).

Mice were treated as described and were monitored every twelve hours using the body condition scoring system. Mice were euthanized when they scored 2 or less and the day/time was recorded (n=5 or 6 for each group). P<0.05 for SN38 treatment versus all other groups.

The average increase in survival versus tumor control for the SN38 treatment group was 4.5 days, a 20% increase in life expectancy post tumor insertion. The average increase in survival versus tumor control for the doxycycline control group was 2 days, a 9.5% increase in life expectancy post tumor insertion. The average increase in survival for the SN38 treatment group versus the doxycycline control group was 2.5 days, a 10% increase in life expectancy post tumor insertion.

3. Discussion

Here we have shown for the first time that a prodrug/prodrug activating enzyme system self-contained within tumor-homing cells can significantly prolong the lives of mice bearing i.p. pancreatic tumors. Mouse RAW 264.7 monocyte-like cells were engineered to synthesize an intracellular form of rabbit CE in a tightly regulated fashion. At the same time, the potent anticancer drug SN38 was rendered harmless to the delivery cells by conjugating it to dextran, so it could be carried within the targeting cells themselves. The conjugation to dextran allowed internalization by the tumor-tropic DS monocyte-like cells but did not allow escape from them until it was cleaved by InCE after activation of the gene by doxycycline. Hence, it was not necessary to systemically administer irinotecan, precluding multiple side effects. Multiple levels of control were built into the system to preclude damage to normal tissues while delivering a potent chemotherapy in localized fashion to the tumor (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Model of developed system.

(1) DS monocyte-like cells were loaded with SN38-Dextran prodrug and injected intraperitoneally into mice bearing Pan02 tumors. The monocyte-like cells specifically infiltrated the tumors. (2) Three days after injecting monocyte-like cells, doxycycline was injected intraperitoneally. The doxycycline disables the tet repressor, activating the InCE which cleaves the prodrug into active SN38. The SN38 is then released from the cell and taken up by nearby cancer cells.

Irinotecan is the water-soluble form of camptothecin[31-33] and is currently used to treat several types of human cancer and is approved for treating colorectal carcinoma.[7,34] However, irinotecan has multiple side effects, such as neutropenia and severe diarrhea[23] when it is converted by CE in the liver to SN38, a potent topoisomerase I inhibitor.[35] The side effects are potentiated by UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 glucuronidation of the SN38.[23] A primary benefit of the reported system is that the irinotecan-like SN38-dextran prodrug is hidden from the body inside the delivery cells. This prevents the metabolism of the prodrug to the active SN38 until the prodrug-containing delivery cells reach the tumor site and also further prevents the metabolism of SN38 by glucuronosyltransferase 1A1. Since neither of these events happens systemically, but rather locally in the tumor, the body is spared many of the harmful side effects of irinotecan administration.

Rabbit carboxylesterase is much more efficient than human carboxylesterase in converting irinotecan to SN38.[24] Other reports have shown the effectiveness of using neural progenitor cells transplanted into the brain, where the carboxylesterase is not regulated and is secreted, followed by systemic administration of irinotecan.[24-26] However, rabbit CE secreted extracellularly in human tissue could cause unwanted immunological consequences or inactivation of the enzyme.[36] Thus, an advantage of the self-contained system described here is that the InCE is expressed only intracellulary, taking advantage of the much greater efficiency of the rabbit CE compared to human CE while minimizing exposure to the immune system.

We found that the engineered mouse monocyte-like cells homed effectively to the pancreatic tumors after i.p. administration. Monocytes and/or macrophages are often found as tumor-associated cells.[37] Rat monocytes were shown to efficiently invade rat glioma spheroids in vitro, and peritoneal macrophages specifically migrated to rat gliomas after intravenous or intracarotid administration.[38] Interestingly, in the experiments described here, the mouse monocyte-like cells physically migrated to the tumors within the peritoneal cavity, while normal tissues did not contain monocyte-like cells.

Previous studies have shown slight stimulation of tumor growth when unmodified delivery cells are given, which is not surprising, since these cells are often recruited into tumors as accessory cells (unpublished data). The DS mouse monocyte-like cells either unloaded or loaded with SN38-dextran, but not subjected to doxycycline-induced release of CE, neither reduced nor enhanced tumor growth. Thus, the system described here does not appear to show undesirable consequences from the delivery cell co-existence in the tumor microenvironment.

The dose of SN38 given via the DS monocyte-like cells was determined to be 4 ng, which is a dose of 200 ng/kg, substantially less than the known effective dose of CPT-11 when delivered systemically.[39] If, as we have demonstrated (Figure 3), the monocyte-like cells carry the dose specifically to the tumor, reducing the volume of biodistribution, the effective dose of SN38 in the tumor could reach into the hundreds of micrograms/kilogram, which, considering the low activation of CPT-11,[20] approaches the known effective dose within the tumor.[39] Since the in vivo data showed that the treated mice survived significantly longer than any control group, this would strongly suggest that the DS monocyte-like cells delivered nearly 100% of the SN38 to the tumor with insignificant whole body release.

The only control group that showed any significant survival advantage was the doxycycline control group. Doxycycline has been investigated as an antitumor treatment with some success, although at much higher doses than in the present study.[40-46] No study has ever shown that such a low dose administered so infrequently had a significant tumor-attenuating effect, but these data indicate that doxycycline could have a tumor-attenuating effect at these concentrations. The doxycycline control group also contained unloaded DS monocyte-like cells, so an unknown additive activity between the DS monocyte-like cells and the doxycycline may also have been responsible for the antitumor effect, perhaps due to activation of the InCE gene, although further research would be needed to confirm this. Although the doxycycline control group did show significant survival increases, these increases were not as large as the SN38 treatment group, indicating that the prodrug is necessary for the full antitumor effect.

In this report, we have described the development of a prodrug/regulated prodrug-activating enzyme self-contained within a tumor-homing delivery cell. Thus, the system we describe here holds potential for further development as a stealth enzyme activating prodrug system for targeted therapy of pancreatic and other types of cancer.

4. Materials and Methods

Reagents and Cells

C57BL/6 mice (11 weeks old) were purchased from Charles River (Wilmington, MA). Raw264.7 cells were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA; authenticated by ATCC using cell morphology, karyotype analysis, and cytochrome C oxidase analysis and cultured for less than six months). Pan02 cells were purchased from the DCTD Tumor Repository (NCI) (Frederick, MD, authenticated by NCI using cell morphology and cultured for less than six months). 7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin (SN38) was purchased from AK Scientific (Mountain View, CA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS), PKH26 and dextran (Mw = 70,000 Da) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Doxycycline and the TetOn® system were purchased from Clontech (Mountain View, CA). RPMI, penicillin-streptomycin, Geneticin (G418), hygromycin, and TOPO TA cloning vector pCR 2.1 were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Lithium chloride, thiazolyl blue, sodium hydroxide, dimethylformamide and sodium dodecyl sulfate were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Succinic anhydride, 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide) hydrochloride (EDC), and 4-dimethyl-aminopyridine (4-DMAP) were purchased from Acros Organics (Fair Lawn, NJ). Endo-Free Maxi kit was purchased from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). Turbofect was purchased from Fermentas Life Sciences (Glen Burnie, MD).

Cell Culture

RAW264.7 monocyte-like cells were cultured in RMPI containing 10% FBS and 1X penicillin-streptomycin in a 37 °C humidified incubator with 5% CO2. (DS monocyte-like cells) stable for both the TetOn® activator and InCE were maintained in RPMI medium containing 10% FBS, with G418 (100 ug/ml) and hygromycin (100 ug/ml) added to preserve stable transfection. Pan02 cells were cultured in RPMI with 10% FBS and 1X penicillin-streptomycin in a 37 °C humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

Generation of Double Stable Cells for Expression of InCE

DS Raw264.7 for the TetOn® InCE system had been previously made as follows.[47] The InCE gene was cloned by PCR from a rabbit liver cDNA library from Biochain (Hayward, CA). Primers used were as follows: forward primer, 5’-GCTTGAATTCCGCCACCATGTGGCTCTG-3’ and reverse primer, 5’-CGTGCTAGCTCACAGCTCAATGT-3’. Both primers contained restriction sites for EcoR1 and Nhe1 to facilitate subcloning. The PCR product was run on a 1% agarose gel to confirm proper amplicon size, then excised from the gel and ligated into the TOPO TA cloning vector pCR 2.1 for 20 minutes. After transformation, into Escherichia coli TOP10 competent cells by heat shock (42°C) positive transformants were selected and grown on Luria agar plates containing amp. Then, the InCE gene was excised with EcoR1 and Nhe1and ligated into the pTRE-Tight plasmid. Again, positive transformants were selected using amp and colony PCR. Plasmid containing the InCE gene was isolated from these bacteria using an Endo-Free Maxi kit. We then created a double-stable monocyte-like cell line. First, we transfected RAW 264.7 cells with the pTet-On Advanced plasmid using Turbofect according to manufacturer’s instructions, followed by selection in G418 medium (500ug/ml). We then transfected the selected cells with the InCE-recombinant pTRE-Tight plasmid (InCE), using Turbofect, and selected stable tranformants with hygromycin (500ug/ml).

Tracking Monocyte-like Cells into Tumor Tissue

To test the homing ability of monocyte-like cells on Pan02 tumors, 7×105 Pan02 cells were injected i.p. to two mice on day 0. On day 4, 1×106 PKH26 red fluorescent dye-labeled monocyte-like cells were injected i.p. (manufacturer’s instructions were followed for PKH26 labeling). Mice were euthanized on days 7 and 10, and tissues collected and fixed in buffered neutral formalin. Twenty-four hours after fixation, tissues were incubated in sucrose gradient and snap frozen. 5-8 micron sections were made and stained with Hoechst for nuclear counter-staining; serial sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Synthesis of SN38-Dextran Prodrug

The synthesis of the SN38-dextran prodrug is as follows (Figure 6). Dextran (200 mg, Mw = 70 kDa) was suspended in dry dimethylformamide (5 mL) in a 25 ml 2-necked round bottom flask fitted with a condenser. Lithium chloride (100 mg) was then added to the suspension followed by pyridine (3 mL) and succinic anhydride (183 mg).[48] The reaction mixture was heated for 24 hours under argon at 110 °C. The reaction mixture was then cooled to room temperature and the product was precipitated by pouring the mixture into isopropanol (25 mL). The white precipitate that formed was collected and washed twice with isopropanol (25 mL). This yielded 351 mg of an off-white solid identified as succinic acid-modified dextran.

Figure 6. Synthesis of SN38-dextran prodrug.

200 mg of dextran (1, Mw=70 kDa) was reacted with succinic anhydride (2) in the presence of lithium chloride to give succinic acid-modified dextran (3). (3) was then reacted with SN38 after activation with EDC and 4-DMAP to give SN38-linked dextran (4).

The succinic acid-modified dextran (100 mg) was suspended in dry DMF (7 mL) and warmed until a clear solution was obtained. The solution was chilled to 0 °C and EDC (91 mg) was added along with 4-DMAP (18 mg); the reaction mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 20 minutes. Following this, SN38 (149 mg) was added and the reaction mixture was slowly warmed to room temperature. After stirring the reaction mixture for 24 hours at room temperature, the reaction mixture was suspended in isopropanol (25 mL). An off-white precipitate was collected and washed twice with ispropanol (25 mL). The precipitate was characterized by NMR and identified as SN38-linked dextran.

The amount of SN38 per dextran molecule was measured by suspending the SN38-dextran prodrug in water, cleaving the activatable ester bond, and recovering the released SN38. The SN38-dextran bond was hydrolyzed by raising the pH of the suspension to 13.5 using 1M sodium hydroxide and heating to 95°C for 1 hour in a water bath. The suspension was then cooled to room temperature, and the pH was decreased to 2 using hydrochloric acid. After incubating in hydrochloric acid for 30 minutes, the released SN38 was extracted from the suspension using of dichloromethane:methanol (4:1 v:v, 5 mL). The fluorescence of the dichloromethane solution (excitation λ = 368 nm, emission integrated from λ = 390 to 540 nm) was then measured and compared to a standard curve.

Loading DS Monocyte-like Cells with SN38-Dextran Prodrug and Determination of SN38 Loading Concentration

To determine whether DS monocyte-like cells would take up the SN38-dextran prodrug and the optimal concentration for loading, DS monocyte-like cells were plated in 24 well plates and allowed to come to 70% confluency. Medium was removed from the cells and fresh medium was added containing SN38-dextran (0 to 500 μg/mL). The cells were left overnight; in the morning (18 hours later) the medium was removed, the cells were washed with PBS, and fresh medium (without SN38-dextran) was added. After washing, loading was confirmed by viewing the cells in a fluorescence microscope using a DAPI filter (SN38 excitation/emission overlays the DAPI filter). Cytotoxicity of the prodrug was measured using the MTT assay.

For injections, DS monocyte-like cells were cultured to 70% confluency in T75 flasks. Sixteen hours before using the cells, the medium was removed and 10 mL of fresh medium was added. Fourteen hours before using the cells, cells for groups 3 and 5 (see below) were given the SN38-dextran prodrug (100 μg, 10 μg/mL), which was added to the medium in PBS (53 μL) and mixed well. At the same time, cells for groups 1, 2, and 4 were given PBS 53 μL without any SN38-dextran prodrug. The SN38-dextran prodrug was left on the cells overnight. The next morning, the medium was removed, the cells were washed with PBS, and fresh medium was added. The cells were lifted by scraping and counted in a hemocytometer using trypan blue. The correct cell density was attained by spinning the cells in 15 mL conical tubes at 1000 RPM for 5 minutes and then resuspending in the correct volume of PBS to give 2,000,000 cells in 100 μL.

To determine the amount of SN38-dextran that was loaded in the cells, DS monocyte-like cells were loaded with SN38-dextran as described above for injections. Cells were lifted by scraping and were counted in a hemocytometer using trypan blue. The cells were then centrifuged at 1000 RPM for 5 minutes and resuspended in PBS (5 mL). The cell suspension was then disrupted using a sonicator tip. The SN38-dextran bond was hydrolyzed by raising the pH of the cell lysate to 13.5 using 1M sodium hydroxide and heating to 95°C for 1 hour in a water bath. The cell lysate was then cooled to room temperature and the pH was brought to 2 using hydrochloric acid. After incubating in hydrochloric acid for 30 minutes, the released SN38 was extracted from the cell lysate using of dichloromethane:methanol (4:1 v:v, 5 mL). The fluorescence of the dichloromethane solution (excitation = 368 nm, emission integrated from 390 to 540 nm) was then measured and compared to a standard curve.

In Vivo Experiment

C57BL/6 mice (11 weeks old) were injected i.p. with 700,000 Pan02 cells in PBS (100 μL) on day 0 to generate a murine model of disseminated pancreatic cancer. These mice were then randomly divided into five groups as follows: (1) tumor control; (2) monocyte-like cells control; (3) SN38 control; (4) doxycycline control; and (5) SN38 treatment. A negative control group for comparison was not injected with tumors (n of all groups is 5 or 6 mice). Group 1 (tumor control group) received tumors only (as described above) with no treatments. Group 2 (monocyte-like cells control group) received tumors and was treated with unloaded DS monocyte-like cells (as described below). Group 3 (SN38 control group) received tumors and was treated with SN38-dextran loaded DS monocyte-like cells (as described below). Group 4 (doxycycline control group) received tumors and was treated with unloaded DS monocyte-like cells and doxycycline (as described below). Group 5 (SN38 treatment group) received tumors and was treated with SN38-dextran loaded DS monocyte-like cells and doxycycline (as described below).

On day 5, 2,000,000 DS monocyte-like cells loaded with the SN38-dextran prodrug were injected in PBS (100 μL) i.p. to groups 3 and 5. Groups 2 and 4 also received 2,000,000 DS monocyte-like cells which were not loaded with the SN38-dextran prodrug. Group 1 received PBS (100 μL) i.p. This procedure was repeated on days 9 and 13.

After giving the monocyte-like cells two days to infiltrate the tumors, on day 7, doxycycline (30 mg/kg) was injected i.p. in PBS (100 μL) to groups 4 and 5. Groups 1, 2 and 3 received PBS (100 μL) i.p. without any doxycycline. This procedure was repeated on days 11 and 15.

After three rounds of treatments, the mice were closely observed and allowed to continue until they displayed signs of clinical symptoms of cancer, at which point they were euthanized using CO2, and the tumors were collected and weighed.

All animal experiments were approved by the authors’ IACUC Institutional Review Board.

Duration to Clinical Symptoms

The measured outcome for this study was mouse survival. To minimize potential pain and distress of the mice, however, a system was developed that allowed the euthanasia of the mice shortly before they actually would have died. A 15 point scoring system was developed based on the body condition score and a rubric was created to score the mice. The five main scores were 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 based on the body condition of the mice (primarily the spine and dorsal pelvic bone prominence) with a score of 3 indicative of a healthy mouse. This initial score was then modified by the presence of extreme lethargy with dehydration, obvious ataxia, head tilt, severe hunching, limb dragging, severe raised hair, obvious Harderian gland secretions, obvious ascites with labored breathing, or bloody tail. If pronounced, these symptoms led to a subtraction of 1 point from the BCS score. The numerical score could then be modified by a + or − designation. Mild cases of these symptoms would lead to a downgrade from a 3+ to a 3 or 3- score. The mice were scored by this system every 12 hours and any mouse that scored a 2 or less was euthanized and the day/time was recorded. The euthanasia day/time data were then treated like survival data and modeled using Kaplan-Meier statistics to determine the statistical significance of the data.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by NIH grant number P20 RR016475 from the INBRE Program of the National Center for Research Resources. We also thank the Kansas Bioscience Authority and the NIH (NIH grant # 1R21CA135599 and NIH-COBRE grant P20 RR0117686) for supporting this work.

Footnotes

Supporting information is available on the WWW under http://www.small-journal.com or from the author.

Contributor Information

Dr. Matthew T. Basel, Email: mbasel@vet.ksu.edu, 1600 Denison Ave., Coles Hall 228, Department of Anatomy and Physiology, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66506 (U.S.A.).

Mr. Sivasai Balivada, 1600 Denison Ave, Coles Hall 228, Department of Anatomy and Physiology, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66506 (U.S.A.)

Dr. Tej B. Shrestha, 1600 Denison Ave, Coles Hall 228, Department of Anatomy and Physiology, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66506 (U.S.A.)

Dr. Gwi-Moon Seo, 1600 Denison Ave, Coles Hall 228, Department of Anatomy and Physiology, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66506 (U.S.A.)

Ms. Marla M. Pyle, 1600 Denison Ave, Coles Hall 228, Department of Anatomy and Physiology, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66506 (U.S.A.)

Dr. Masaaki Tamura, 1600 Denison Ave, Coles Hall 228, Department of Anatomy and Physiology, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66506 (U.S.A.)

Dr. Stefan H. Bossmann, Chem-Biochem Building 143, Department of Chemistry, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66506 (U.S.A.)

Dr. Deryl L. Troyer, Email: troyer@vet.ksu.edu, 1600 Denison Ave., Coles Hall 228, Department of Anatomy and Physiology, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66506 (U.S.A.).

References

- 1.Johnson KA, Brown PH. Semin Oncol. 2010;37:345–358. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen TM, Cullis PR. Science. 2004;303:1818–1822. doi: 10.1126/science.1095833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moses MA, Brem H, Langer R. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:337–341. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00276-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alley SC, Okeley NM, Senter PD. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14:529–537. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.06.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warnecke A, Fichtner I, Sass G, Kratz F. Arch Pharm (Weinheim) 2007;340:389–395. doi: 10.1002/ardp.200700025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu S, Bugge TH, Leppla SH. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17976–17984. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011085200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azrak RG, Cao S, Slocum HK, Toth K, Durrani FA, Yin MB, Pendyala L, Zhang W, McLeod HL, Rustum YM. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1121–1129. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0913-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedlos F, Denny WA, Palmer BD, Springer CJ. J Med Chem. 1997;40:1270–1275. doi: 10.1021/jm960794l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greco O, Dachs GU. J Cell Physiol. 2001;187:22–36. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(2001)9999:9999<::AID-JCP1060>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rooseboom M, Commandeur JN, Vermeulen NP. Pharmacol Rev. 2004;56:53–102. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aboody KS, Brown A, Rainov NG, Bower KA, Liu S, Yang W, Small JE, Herrlinger U, Ourednik V, Black PM, Breakefield XO, Snyder EY. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:12846–12851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.23.12846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arbab AS, Pandit SD, Anderson SA, Yocum GT, Bur M, Frenkel V, Khuu HM, Read EJ, Frank JA. Stem Cells. 2006;24:671–678. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Palma M, Mazzieri R, Politi LS, Pucci F, Zonari E, Sitia G, Mazzoleni S, Moi D, Venneri MA, Indraccolo S, Falini A, Guidotti LG, Galli R, Naldini L. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:299–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ganta C, Chiyo D, Ayuzawa R, Rachakatla R, Pyle M, Andrews G, Weiss M, Tamura M, Troyer D. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1815–1820. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamizo A, Marini F, Amano T, Khan A, Studeny M, Gumin J, Chen J, Hentschel S, Vecil G, Dembinski J, Andreeff M, Lang FF. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3307–3318. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rachakatla RS, Marini F, Weiss ML, Tamura M, Troyer D. Cancer Gene Ther. 2007;14:828–835. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7701077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Studeny M, Marini FC, Champlin RE, Zompetta C, Fidler IJ, Andreeff M. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3603–3608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Studeny M, Marini FC, Dembinski JL, Zompetta C, Cabreira-Hansen M, Bekele BN, Champlin RE, Andreeff M. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1593–1603. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arimori K, Kuroki N, Kumamoto A, Tanoue N, Nakano M, Kumazawa E, Tohgo A, Kikuchi M. Pharm Res. 2001;18:814–822. doi: 10.1023/a:1011040529881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang B, Desai A, Tang S, Thomas TP, Baker JR., Jr Org Lett. 2010;12:1384–1387. doi: 10.1021/ol1002626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsuzaki T, Yokokura T, Mutai M, Tsuruo T. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1988;21:308–312. doi: 10.1007/BF00264196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Reilly S, Rowinsky EK. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1996;24:47–70. doi: 10.1016/1040-8428(96)00211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Innocenti F, Undevia SD, Iyer L, Chen PX, Das S, Kocherginsky M, Karrison T, Janisch L, Ramirez J, Rudin CM, Vokes EE, Ratain MJ. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1382–1388. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Danks MK, Morton CL, Krull EJ, Cheshire PJ, Richmond LB, Naeve CW, Pawlik CA, Houghton PJ, Potter PM. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:917–924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Danks MK, Yoon KJ, Bush RA, Remack JS, Wierdl M, Tsurkan L, Kim SU, Garcia E, Metz MZ, Najbauer J, Potter PM, Aboody KS. Cancer Res. 2007;67:22–25. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aboody KS, Bush RA, Garcia E, Metz MZ, Najbauer J, Justus KA, Phelps DA, Remack JS, Yoon KJ, Gillespie S, Kim SU, Glackin CA, Potter PM, Danks MK. PLoS One. 2006;1:e23. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Humerickhouse R, Lohrbach K, Li L, Bosron WF, Dolan ME. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1189–1192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsui M, Shimizu Y, Kodera Y, Kondo E, Ikehara Y, Nakanishi H. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:1670–1677. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01587.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muthana M, Giannoudis A, Scott SD, Fang H, Coffelt SB, Morrow FJ, Murdoch C, Burton J, Cross N, Burke B, Mistry R, Hamdy F, Brown NJ, Georgopoulus L, Hoskin P, Essand M, Lewis CE, Maitland NJ. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1805–1815. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baek S, Makkouk AR, Krasieva T, Sun C, Madsen SJ, Hirschberg H. J Neurooncol. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0511-3. EPub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sawada S, Miyasaka T. Curr Pharm Design. 1995;1:113–132. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sawada S, Okajima S, Aiyama R, Nokata K, Furuta T, Yokokura T, Sugino E, Yamaguchi K, Miyasaka T. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1991;39:1446–1450. doi: 10.1248/cpb.39.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miyasaka T, Nokata K, Sugino E, Mutai M. 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu MH, Yan B, Humerickhouse R, Dolan ME. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2696–2700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Ark-Otte J, Kedde MA, van der Vijgh WJ, Dingemans AM, Jansen WJ, Pinedo HM, Boven E, Giaccone G. Br J Cancer. 1998;77:2171–2176. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oosterhoff D, Pinedo HM, van der Meulen IH, de Graaf M, Sone T, Kruyt FA, van Beusechem VW, Haisma HJ, Gerritsen WR. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:659–664. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Solinas G, Germano G, Mantovani A, Allavena P. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86:1065–1073. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0609385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strik HM, Hulper P, Erdlenbruch B, Meier J, Kowalewski A, Hemmerlein B, Gold R, Bahr M. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:865–871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bissery MC, Vrignaud P, Lavelle F, Chabot GG. Anticancer Drugs. 1996;7:437–460. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199606000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duivenvoorden WC, Popovic SV, Lhotak S, Seidlitz E, Hirte HW, Tozer RG, Singh G. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1588–1591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duivenvoorden WC, Vukmirovic-Popovic S, Kalina M, Seidlitz E, Singh G. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:1526–1531. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shieh JM, Huang TF, Hung CF, Chou KH, Tsai YJ, Wu WB. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1171–1184. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00746.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Son K, Fujioka S, Iida T, Furukawa K, Fujita T, Yamada H, Chiao PJ, Yanaga K. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:3995–4003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van den Bogert C, Dontje BH, Kroon AM. Cancer Res. 1988;48:6686–6690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van den Bogert C, Dontje BH, Kroon AM. Leuk Res. 1985;9:617–623. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(85)90142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van den Bogert C, Dontje BH, Kuzela S, Melis TE, Opstelten D, Kroon AM. Leuk Res. 1987;11:529–536. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(87)90088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seo GM, Rachakatla RS, Balivada S, Pyle M, Shrestha TB, Basel MT, Myers C, Wang H, Tamura M, Bossmann SH, Troyer DL. Mol Biol Rep. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-0720-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arranz F, Sanchez-Chaves M, Ramirez JC. Angew Makromol Chem. 1992;194:79–89. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.