ABSTRACT

Marijuana and alcohol use are associated with increased sexual risk behavior among justice-involved youth. A multi-behavior intervention may reduce all three risk behaviors. The purpose of this study is to examine the relationships among multiple risk behaviors and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) constructs guiding the development of the Motivating Adolescents to Reduce Sexual risk (MARS) intervention. We describe the MARS study design to inform the process through which a multi-behavior intervention trial can be implemented and evaluated. Participants completed questionnaires prior to randomization to one of three interventions. Relationships were found between TPB constructs and risk behavior. A single latent variable was inadequate to capture all three risk behaviors. Interventions to reduce sexual risk behavior can include content related to the role of substance use in influencing sexual risk behavior with only minimal modifications to the curriculum, and preliminary data suggest a common theory can apply across risk behaviors.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13142-013-0192-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEYWORDS: Justice-involved youth, Risky sexual behavior, Alcohol use, Marijuana use, Theory of planned behavior

Compared with the general adolescent population, justice-involved youth are younger at first intercourse, have a greater number of sexual partners, and lower rates of condom use [1]. These risky sexual behaviors result in higher rates of unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STI). Substance use is a critical risk factor for risky sexual behavior, and the available data suggest that the relationship of substance use to sexual risk may be strongest for youth [2].

ALCOHOL USE, MARIJUANA USE, AND RISKY SEXUAL BEHAVIOR

In 2011, 70 % of 12th graders reported trying alcohol and 50 % reported being drunk at least once [3]. Youth involved with the criminal justice system are at even greater risk [4] with an estimated 88.7 % of incarcerated youth reporting current use of alcohol [5]. Data support a relationship between alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among justice-involved youth [6]. For example, justice-involved youth who indicated using alcohol before sexual intercourse were less likely to have used a condom [7].

Roughly 46 % of 12th graders from the general adolescent population in 2011 used marijuana at least once in their lifetime [8]. In comparison to the general adolescent population, youth involved with the criminal justice system have higher rates of marijuana use, 3.5 times that of their non-justice-involved peers [5, 6, 9, 10]. Like alcohol use, marijuana use has been associated with increased sexual activity, increased number of sexual partners, and unprotected sexual intercourse [11, 12], and justice-involved youth who meet the criteria for marijuana dependence have steeper declines in condom use over time [13]. Given that justice-involved youth use marijuana and alcohol more frequently than any other drug, and given the suggested link between alcohol use, marijuana use and sexual risk behavior, a strategy that includes both of these substances in a sexual risk reduction intervention may be an effective way to reduce all three behaviors within this high-risk population [14–16].

HIV/STI INTERVENTIONS

Schmiege and colleagues [17], showed that an intervention designed to reduce sexual risk behavior and alcohol risk among justice-involved youth was more effective than one designed to reduce sexual risk alone. Further studies suggest that including alcohol and marijuana content in a sexual risk reduction intervention may offer the best strategy to reduce risk overall [6, 18]. Those who have aimed to integrate multiple risk behaviors into brief interventions have had inconsistent success, suggesting that there may be barriers to addressing three distinct behaviors (sexual risk, alcohol use, marijuana use) in a single intervention. The primary challenge is how to effectively reduce risk across all behaviors without compromising the effects of the intervention on any one. For example, a multiple health and risk behavior intervention in a randomized controlled trial with high school-aged youth had significant effects on only two of seven targeted behaviors and these effects were small [19].

MI/MET AND THE THEORY OF PLANNED BEHAVIOR

A successful multi-behavior intervention requires a delivery system that is maximally flexible so that the same system can be used throughout the intervention. One successful approach to risk reduction is motivational enhancement therapy (MET); adapted from motivational interviewing (MI), a technique that has been effectively utilized in group settings. Research using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) suggests that neurocognitive effects of MI result in reduced substance use in high-risk youth [20] and alcohol using adults [21]. Moreover, brief motivational interventions, like MI/MET, have been successfully utilized for the reduction of substance use and risky sexual behavior in adolescents (c.f., [22–27]). MI-based approaches, in particular, show promise for both youth in general, and justice-involved youth [14], because the non-confrontational and supportive approach of MET is an excellent developmental fit for youth involved in the justice system. Other intervention modalities have shown some evidence of success in the substance use domain. For example, mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) may reduce alcohol relapse in adults [28] and may influence some aspects of behavior in young people that could reduce risky behavior (i.e., MBSR increases executive function in youth) [29]. Although there is promise for other intervention modalities, to date, we believe MI/MET has the strongest evidence for decreasing adolescent problem behavior in general, and substance use and sexual risk in particular [14, 22–27]. Given the developmental and temporal fit as well as the empirical evidence base, we elected to utilize MI/MET as the intervention modality in this study.

Selection of intervention content was derived from the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB; [30]). The TPB posits that intentions to engage in a behavior are the most proximal determinant of behavior, and that intentions are determined by attitudes towards the behavior, norms supportive of the behavior, and self-efficacy for or perceived control over the behavior. The mediators of change in the TPB are highly consistent with the strategies of behavior change utilized in MET. In prior work we have successfully utilized MET as a delivery system for enhancing TPB constructs [17]. There are a number of theories to choose from when creating a theory-based intervention, and our selection of the TPB was guided in part by our view that the core constructs of the TPB are well-represented (sometimes using different terminology) in most of the validated theories of behavior and behavior change (c.f., [31, 32]). Further, the TPB predicts a vast array of health behaviors [33–35] and sexual risk behavior change among high-risk youth [14].

The goal of the overall project is to compare risk behaviors 3, 6, 9, and 12 months post-intervention using a three group randomized dismantling design [36] comparing three sexual risk reduction curricula: SRRI + ETOH + MJ (targeting sexual risk reduction, alcohol use and marijuana use), SRRI + ETOH (targeting sexual risk reduction and alcohol use) or SRRI (targeting sexual risk reduction only). The intervention includes self-efficacy skill-building tasks (i.e., condom demonstration and hands-on practice) as well as a focus on social situations most likely to exacerbate risk (e.g., “when you are at a party with a new boy/girl that you like and he/she says that he/she does not like the feeling of condoms,” and “when you and your partner have been drinking and/or using marijuana”) followed by adolescent-led generation of risk reduction strategies. We see two potential outcomes: first, an intervention that targets the three most common (and interrelated) health risk behaviors among youth is the most effective in reducing these behaviors. Second, trying to do “too much” all in one intervention will result in smaller effects on some or all of the behaviors (c.f., [19]). If we find that a sexual risk reduction intervention alone is equally as effective as either of the interventions including substance use content, this simplifies intervention technology for this population tremendously.

Since we do not have intervention outcome data that speak to these larger goals, the current analysis presents tests of intermediate questions that facilitate the larger study. Given that the TPB guided the content of all three interventions, the first goal is to determine whether TPB constructs assessing sexual risk generally are distinct from TPB constructs assessing sexual risk in conjunction with alcohol and marijuana use. Based on our prior work [37], we hypothesize that they will not be distinct and can be combined into single scales. In order to eventually test mediational models of intervention effects, we need to define the outcome variable. Thus, the second goal of these analyses is to examine whether it is possible to combine both sexual risk and substance use in conjunction with sexual risk into a single latent variable or if multiple latent variables are necessary. Our final goal is to explore TPB-based relationships between these new measures of TPB constructs and the latent risk behavior variable/s.

METHODS

All data for these analyses were drawn from assessments completed prior to randomization to intervention, so the data were unaffected by intervention condition.

Procedures and recruitment

Data were analyzed for 282 justice-involved youth (56.4 % male). Participants thus far are an average of 15.89 years of age (SD = 1.17), the majority are Hispanic (67 %), and all were residing in a youth detention facility at the time of recruitment (see Table 1 for demographic information). Participants are recruited via research assistants visiting the local county detention center in New Mexico who announce the opportunity to participate in a study conducted by researchers at the University of New Mexico (UNM). Eligible youth must: (1) be between the ages of 14 and 18, (2) speak English, (3) have a remaining term in detention of less than 1 month, and (4) be willing to sign a release form allowing access to their STI test results if they were tested at intake. For youth under the age of 18, once adolescent assent is obtained, parent/guardian consent is obtained via telephone [17]. Participants are paid US$20 for completing the baseline measures, optional DNA sample and STI test, and US$10 for completing the intervention and post-test assessments. Due to high rates of suboptimal literacy in justice-involved populations, questionnaires are administered via audio computer-assisted self-interviewing technology on laptop computers, which assists participants by reading questions aloud over headphones as they are presented on the screen [17]. This project was approved by the UNM Human Research Review Committee and the national Office of Human Research Protections; in addition to obtaining a federal certificate of confidentiality from National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| (N = 282) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) or % | Possible range |

| Demographics | ||

| Ethnicity (% Hispanic) | 67 | |

| Age | 15.89 (1.17) | 14–18 |

| Gender (% female) | 43.6 | |

| Theory of planned behavior variables | ||

| Attitudes | 5.03 (1.37) | 1–7 |

| Norms | 2.41 (.82) | 1–4 |

| Self-efficacy | 3.24 (.49) | 1–4 |

| Intentions | 2.60 (.64) | 1–4 |

| Sexual behavior | ||

| Ever had sexual intercourse (%) | 93.8 | |

| Age at first sexual experience | 12.92 (1.74) | |

| No. of lifetime sexual partners | 10.77 (13.56) | 1–100 |

| Frequency of condom use (lifetime) | 3.01 (1.15) | 1–5 |

| Frequency of MJ use before intercourse (lifetime) | 3.02 (1.19) | 1–5 |

| Frequency of ALC use before intercourse (lifetime) | 2.69 (.98) | 1–5 |

| Frequency of MJ use before intercourse (past 3 months) | 2.68 (1.35) | 1–5 |

| Frequency of ALC use before intercourse (past 3 months) | 3.82 (2.59) | 1–5 |

| Alcohol use | ||

| Age at first drink | 11.69 (2.47) | |

| Frequency of at least one drink (past 3 months) | 3.82 (2.59) | 1–9 |

| AUDIT | 9.73 (8.12) | 0–40 |

| Marijuana Use | ||

| Age at first use | 10.96 (2.43) | |

| Frequency of MJ use (past 3 months) | 5.67 (3.46) | 1–9 |

| MDS | 2.91 (2.83) | 0–10 |

| Impulsivity | 11.27 (4.15) | 1–19 |

Self-report assessments

TPB

Participants answered a range of questions reflecting the core constructs of the TPB. Except for attitudes, which are considered a global measure, the TPB constructs have questions that address specific cognitions regarding both condom use alone and condom use in the context of substance use. Thus, attitudes are excluded from the correlational analyses that aim to assess the relationships between TPB constructs with and without substance use. Descriptions of the measures of model constructs can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Model constructs, item sources, coefficient alpha (α), and sample items

| Construct name | Items | Source | α | Sample item |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condom use attitudesa | 7 | [59] | .89 | On a scale from 1 to 7, where 1 means unhealthy and 7 means healthy, for me, using a condom every time I have sex would be… |

| Condom use self-efficacy Substance use + condom use self-efficacy | 19 | [60, 61] | .84 | I am confident in my ability to put a condom on. I could remember to use a condom even after I have been drinking. |

| Condom use norms Substance use + condom use norms | 8 | [17, 39, 62] | .82 | Most of my friends use condoms when they have sex. Most of my friends use condoms when they’re smoking marijuana. |

| Condom use intentions Substance use + condom use intentions | 18 | [17, 39, 62] | .89 | How likely is it that you will buy or get condoms in the next 3 months? How likely is it that you will use a condom when you have been smoking marijuana in the next 3 months? |

aScored on a 1–7 scale and does not include items to assess substance use + condom use attitudes

Impulsivity

Impulsivity was assessed with the 19-item Impulsive Sensation Seeking Scale (IMPSS; [38]). Participants indicated (true = 1, false = 0) whether each statement described them (e.g., “I like doing things just for the thrill of it.”). Scores were summed and higher scores indicated a greater tendency towards impulsivity, α = .80.

Sexual history

Consistent with prior studies [14, 39], participants were first asked whether they have ever had sexual intercourse (yes/no). Those saying yes then indicated how old they were the first time, how many sexual partners they have had, and frequency of intercourse (1 = a few times a year, 2 = once a month, 3 = once a week, 4 = two to three times a week, 5 = four to five times a week, and 6 = almost every day). To assess lifetime frequency of condom use, participants reported how often they used condoms (1 = never to 5 = always), which is reverse-coded so that higher numbers reflect more unprotected sexual intercourse. To assess substance use during sexual intercourse, participants were asked “Of all the times you’ve had sexual intercourse, how much of the time have you drank alcohol before sex?” and “Of all the times you’ve had sexual intercourse, how much of the time have you smoked marijuana before sex?” (1 = never to 5 = always). Participants answered the same questions about the past 3 months.

Alcohol use and dependence

Alcohol use was evaluated via self-report with a variation of the measure used by White and Labouvie [40]. First, youth indicated if they had ever had an alcoholic drink. Those who indicated using alcohol then reported their frequency of use in the last 3 months (1 = never to 9 = every day), their typical quantity of drinks in one sitting (1 = none, 2 = one drink, 3 = two to three drinks, 4 = four to six drinks, 5 = seven to nine drinks, 6 = 10 to 12 drinks, 7 = 13–15 drinks, 8 = 16–18 drinks, 9 = 19–20 drinks, 10 = more than 20 drinks), and their frequency of getting drunk when drinking in the past 3 months (1 = never to 5 = always). Alcohol dependence over the past 3 months was assessed using the 10-item Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT; [41]), (α = .86 in this sample). Of the 266 participants who had ever drank alcohol, 78.2 % had a total AUDIT score of 4 or more, suggesting that over two thirds of the drinkers in this sample could be classified as engaging in hazardous drinking and/or be considered alcohol dependent [42].

Marijuana use and dependence

Participants first indicated via self-report if they had ever smoked marijuana. Those who used marijuana then reported the age at which they smoked marijuana for the first time and how often they smoked marijuana (1 = never to 9 = every day). Marijuana dependence was assessed using the Marijuana Dependence Scale (MDS; [43]). Participants were asked to indicate if they had experienced 10 symptoms related to marijuana use in the past 3 months (e.g., “spending a significant amount of time trying to obtain, use, or recover from marijuana”), and participants respond “yes” or “no” to each item (α = .84). Scores range from 0 to 10 with a score of 3 or more indicative of dependence [43]. Of the 274 participants who had ever smoked marijuana, 47.1 % endorsed 3 or more items on the scale, suggesting that nearly half of the marijuana smokers in this sample could be classified as marijuana dependent.

The levels of alcohol and marijuana use in this sample are consistent with self-reported use from similar populations in our own work [7, 14, 17, 44] and by other investigators [45–47].

Sexually transmitted infection sample collection and testing

As an objective measure of sexual risk behavior (c.f., [48]), participants who were not tested at intake by the detention center are asked to provide a urine sample to test for chlamydia and gonorrhea (those who were tested have results on file with the detention center). A urine sample is collected from participants at baseline, and again at the 12-month follow-up assessment. Samples are assayed for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae using polymerase chain reaction analyses. In the event of a positive test, participants are treated with one gram azithromycin for chlamydia and 400 mg cefixime for gonorrhea as per our study pediatrician’s recommendations and supervision.

Intervention protocol and posttest assessments

After completing the baseline assessment, participants are randomly assigned into one of the three interventions (SRRI + ETOH + MJ, SRRI + ETOH, or SRRI). All three interventions are delivered using a one-session group format consisting of four to six participants and two group leaders (i.e., a masters-level MI/MET trained intervention leader and a research assistant). The sessions have identical structure and length (3 h in length: 2 h for the intervention and 1 h for pre- and posttest assessments). Each session starts with a brief introduction to remind participants that everything they say is completely confidential as well as to establish group rules to ensure everyone feels comfortable sharing their experiences in a group setting. More information on the curriculum is available in the electronic supplementary material.

RESULTS

The main goal of these analyses was to explore TPB-based relationships between the model constructs and risk behavior. To do this, we first evaluated whether TPB constructs assessing condom use generally were distinct from TPB constructs assessing condom use in the context of alcohol or marijuana use using correlations among the constructs. Our second goal was to examine whether it was possible to combine both sexual risk and substance use in conjunction with sexual risk into a single latent variable or if multiple latent risk behavior variables were needed using structural equation modeling. We then estimated a path analytic model of risk behavior to assess relationships between TPB constructs and behavior.

Relationships among theory of planned behavior constructs

TPB constructs of subjective norms, self-efficacy, and condom use intentions were assessed separately for each of the risk behaviors examined: condom use, condom use in the context of alcohol use, and condom use in the context of marijuana use. Correlations among all the relevant constructs are provided in Table 3. There are large and significant correlations between the total composite scores for norms, self-efficacy, and intentions and the risk-specific measures (all rs > .695), suggesting a strong degree of overlap in those relationships. For this reason, the composite scores for these TPB variables were used for the path analysis.

Table 3.

Correlations for the TPB model constructs and substance use

| Norms (NRM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condom use NRM | MJ norms | ALC norms | Total norms | |

| Condom use NRM | 1 | |||

| MJ norms | .724*** | 1 | ||

| ALC norms | .628*** | .673*** | 1 | |

| Total norms | .929*** | .881*** | .831*** | 1 |

| Self-efficacy (SE) | ||||

| Condom use SE | MJ SE | ALC SE | Total SE | |

| Condom SE | 1 | |||

| MJ SE | .695*** | 1 | ||

| ALC SE | .862*** | .604*** | 1 | |

| Total SE | .773*** | .759*** | .696*** | 1 |

| Intentions (INT) | ||||

| Condom use INT | MJ INT | ALC INT | Total INT | |

| Condom use INT | 1 | |||

| MJ INT | .610*** | 1 | ||

| ALC INT | .611*** | .701*** | 1 | |

| Total INT | .814*** | .880*** | .909*** | 1 |

Note: condom use attitudes were not assessed with substance and thus are not included here

*p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001

Risk behavior

Means and standard deviations for risk behaviors and impulsivity are presented in Table 4. Only 8.4 % of participants reported that they always used condoms during sexual intercourse. Fully 32.3 % of sexually active young people indicated almost always or always using marijuana before engaging in sexual intercourse, and only 16.7 % said they never used marijuana before sexual intercourse. Sixteen percent indicated almost always or always using alcohol before engaging in sexual intercourse, and only 16.3 % said they never used alcohol before sexual intercourse. There were 8.7 % of participants who tested positive for chlamydia, 1.8 % for gonorrhea, and .4 % for both chlamydia and gonorrhea. The majority of participants (94.3 %) indicated that they had consumed alcohol at least once in their lifetime, and reported drinking on average 3.82 (SD = 2.59) on our 9-point scale, roughly corresponding to drinking two to three times a month. The majority of participants (96.4 %) indicated that they had smoked marijuana and had an average marijuana use score of 5.67 (SD = 3.46) on our 9-point scale, roughly corresponding to smoking marijuana once a week. Frequency of intercourse was positively related to frequency of marijuana use before intercourse and marginally related to frequency of alcohol use before intercourse. Unprotected intercourse was positively related to impulsivity, but was not related to marijuana or alcohol use before intercourse. Although the lack of a relationship between substance use and unprotected intercourse may seem counterintuitive, it is consistent with the literature. Some studies do not find an association [49, 50], while others find that those who drink or smoke marijuana more frequently also use condoms less often [51, 52]. Frequency of marijuana use and alcohol use before intercourse were positively associated and both were positively related to impulsivity (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlations, raw means, and standard deviations of model constructs

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Frequency of intercoursea | – | ||||||||

| 2. Frequency of unprotected intercoursea | .109 | – | |||||||

| 3. Marijuana before intercoursea | .171** | .095 | – | ||||||

| 4. Alcohol before intercoursea | .114 | .069 | .291** | – | |||||

| 5. Condom use intentions | −.168** | −.421** | −.040 | −.042 | – | ||||

| 6. Condom use norms | −.092 | −.367** | −.032 | −.079 | .494** | – | |||

| 7. Condom use self-efficacy | −.053 | −.452** | −.117 | −.092 | .414** | .309** | – | ||

| 8. Condom use attitudesa | −.194** | −.392** | −.115 | −.078 | .476** | .366** | .480** | – | |

| 9. Impulsivitya | .047 | .177** | .169** | .281** | −.195** | −.201** | −.294** | −.270** | – |

| Mean | 3.48 | 2.99 | 3.02 | 2.69 | 2.82 | 2.41 | 3.24 | 5.03 | 11.27 |

| Standard deviation | 1.65 | 1.15 | 1.19 | 0.98 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.49 | 1.38 | 4.15 |

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

aRange for all variables is 1–4 except for: frequency of intercourse (1–6), frequency of unprotected intercourse (1–5), marijuana use in conjunction with sexual intercourse (1–5), and alcohol use in conjunction with sexual intercourse (1–5), condom use attitudes (1–7), and impulsivity (0–1)

Development of latent outcome variables

All four risk behavior variables (i.e., frequency of intercourse, unprotected intercourse, and marijuana and alcohol use before intercourse) were specified as indicators of a single latent risk behavior outcome variable. The fit of this model was good, Yuan-Bentler scaled χ2 (2, N = 282) = .865, p > .05, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 1.00, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .000 (90 % CI.000–.097) [53]. Next, we investigated whether multiple latent risk behavior variables were better outcome variables of risk behavior. Risky sexual behavior was the first latent variable estimated, and it consisted of frequency of intercourse and frequency of unprotected sexual intercourse. The second latent variable assessed substance use in conjunction with risky sexual behavior (i.e., frequency of marijuana and alcohol use before intercourse). The fit of this model was also good, Yuan-Bentler scaled χ2 (4, N = 282) = 9.18, p > .05, CFI = .923, RMSEA = .073 (90 % CI.005–.133) [53]. The single latent risk variable was a slightly better fitting model of risk behavior; however, the assessment of the validity of a model is also determined by the pattern and significance of the factor loadings. Some of the factor loadings (i.e., frequency of alcohol use before intercourse) for the single latent risk variable were only marginal (p < . 10), suggesting that that all four variables were not significantly related to the same underlying construct. In contrast, the factor loadings for the multiple latent risk behavior variables all reached significance (ps < .05). For this reason, two latent risk behavior variables—one reflecting risky sexual behavior and one reflecting substance use prior to sexual activity—were used as the outcome variables for modeling TPB relationships with behavior.

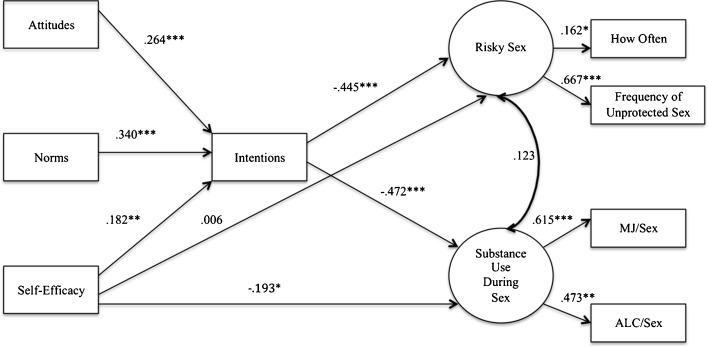

Relationships of TPB variables to behavior

We estimated a path analytic model (c.f., [54]) using Structural Equation Modeling software [55] that followed the structure of the TPB (see Fig. 1) and utilized the two latent risk behavior variables as the outcome. The fit of this model was good, Yuan-Bentler scaled χ2 (14, N = 282) = 23.94, p < .05, CFI = .977, RMSEA = .058 (90 % CI.023–.090), and consistent with the TPB, attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy were significantly and positively related to intentions to engage in safer sexual behavior [53]. Intentions were, in turn, negatively related to risky sexual behavior. Importantly, intentions were also negatively and significantly related to substance use in conjunction with risky sexual behavior (p < .001) such that higher condom use intentions were associated with lower substance use in conjunction with risky sexual behavior. Self-efficacy, on the other hand, was only significantly associated with substance use in conjunction with risky sexual behavior (p < .05); higher condom use self-efficacy scores were related to fewer instances of substance use in conjunction with risky sexual behavior.

Fig 1.

Model with separate sexual risk and substance use with sexual risk latent variables among justice-involved youth. Note: coefficients are standardized path coefficients. Overall model fit: χ2 (14, N = 282) = 23.94, p < .05, CFI = .977, RMSEA = .058 (90 % CI.023–.090). *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

DISCUSSION

Our overarching goal was to describe a multiple risk behavior intervention among justice-involved youth and to inform the process through which a multi-behavior intervention trial can be designed and executed. We were able to demonstrate the feasibility (though not yet the efficacy) of incorporating multiple risk behaviors (alcohol use, marijuana use, and risky sexual behavior) in interventions among justice-involved youth in a rigorous dismantling design.

Consistent with our previous work on alcohol use during intercourse [17], it was not possible to empirically separate attitudes and beliefs regarding condom use more generally versus condom use in the context of substance use. When youth consider condom use, they simply may not have separate beliefs based on the context in which sexual behavior takes place. These findings suggest that the combined TPB variables can be appropriately utilized in mediational analyses of program effects at the conclusion of the trial.

Our analyses also suggested that keeping sexual risk and sexual risk in conjunction with alcohol and marijuana use separate provided the best assessment of risk behavior outcomes, an outcome consistent with prior work in this area [6, 18]. In other words, it may not be the case that an intervention can address “condom use” globally and presume that it will translate to different situations. We further demonstrated that although unprotected sexual behavior and sexual behavior in the context of substance abuse were empirically distinct constructs, norms, intentions, and self-efficacy were associated with these constructs in ways that are consistent with the TPB. Thus, the findings suggest that the same theoretical basis for intervention (here, the TPB) might be effective for reducing unprotected sexual behavior and sexual behavior in the context of substance abuse. This finding is promising for intervention development in that it provides evidence that the same set of theoretical constructs may be equally efficient at explaining related though distinct sets of behavior.

LIMITATIONS

The current analysis is limited by a reliance on self-report data; the sensitive nature of the assessments may have caused biased responding. With regard to substance use, studies including biological verification have shown that in large part most adolescents are truthful in their self-reports (see [56]). These same data suggest when young people are not accurate, they are as likely to underreport as to over report. The data utilized in this particular analysis are also cross-sectional and thus we cannot make any assumptions of causality or directionality in the model. Additionally, the sample analyzed here is only a subset of the primary study and while they are an accurate representation of the potential final sample, the findings must be considered preliminary. Our results are not representative of all youth and may not generalize to adolescents who are not involved with the juvenile justice system or to substances besides alcohol and marijuana. Finally, we recognize that developmental neurocognition is a crucial correlate of youth risk behavior (c.f., [57]). In fact, in another work, we focus on the extent to which neurocognitive variables may be associated with risk taking [58] and may moderate responses to the type of theory-based intervention studied here [44]. Given the focus of the current work on the development of optimal content in an intervention, we do not address the broader questions involving developmental neurocognitive structure and function.

CONCLUSION

The study (Project MARS) from which these preliminary data are drawn aims to determine the most effective way to reduce risky sexual behavior in conjunction with substance use among justice-involved youth. To better isolate the threshold at which a single session, brief intervention can most efficiently reduce risky behavior, these interventions target sexual risk behavior alone, sexual risk behavior in conjunction with alcohol risk, and sexual risk behavior in conjunction with alcohol and marijuana risk. We hope that the ultimate findings from the study inform the most parsimonious approach to the prevention of these three interrelated behaviors, and the results presented here suggest that we will be well-positioned to determine not only which intervention had the strongest effects on behavior, but the mechanisms of change through which those effects occurred.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOC 225 kb)

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by a grant awarded to Angela Bryan from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (1 R01 AA013844-05A1). This is an ongoing trial and is registered at clinicaltrials.gov #NCT01170260. Additional thanks are due to Rachel Thayer, Emilee Prado, and Ross Kalsow for their assistance with preparing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Implications

Policy: Resources should be directed toward developing preventive interventions for justice-involved youth, ideally in a parsimonious way that effectively incorporates the major risk behaviors that this population engages in.

Research: There continues to be a significant gap in how to best integrate multiple risk behaviors within a single intervention; interventions that are able to address the three most common health risk behaviors among youth (i.e., sexual risk, alcohol use, and marijuana use) may have the best potential to reduce these related risks.

Practice: Given that justice-involved youth use marijuana more frequently than they use alcohol and given the suggested link between marijuana use, alcohol use, and sexual risk behavior, a strategy that includes both of these substances in a one-session HIV/STI prevention intervention has the potential to be both efficacious and feasible for use in high-risk populations.

References

- 1.Teplin LA, Mericle AA, McClelland GM, Abram KM. HIV and AIDS risk behaviors in juvenile detainees: implications for public health policy. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(6):906–912. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.6.906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM, McClelland GM, Washburn JJ, Pikus AK. Detecting mental disorder in juvenile detainees: who receives services. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(10):1773–1780. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.067819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2011. Volume II: college students and adults ages 19–50. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan, 2012

- 4.Ho CH, Kingree JB, Thompson MP. Associations between juvenile delinquency and weight-related variables: analyses from a national sample of high school students. Int J Eat Disord. 2006;39(6):477–483. doi: 10.1002/eat.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lebeau-Craven R, Stein L, Barnett N, Colby SM, Smith JL, Canto A. Prevalence of alcohol and drug use in an adolescent training facility. Subst Use Misuse. 2003;38(7):825–834. doi: 10.1081/JA-120017612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosengard C, Stein LA, Barnett NP, Monti PM, Golembeske C, Lebeau-Craven R. Co-occurring sexual risk and substance use behaviors among incarcerated adolescents. J Correct Health Care. 2006;12(4):279–287. doi: 10.1177/1078345806296169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryan AD, Ray LA, Cooper ML. Alcohol use and protective sexual behaviors among high-risk adolescents. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68(3):327–335. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2011. Volume I: secondary school students. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan, 2012

- 9.National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University (CASA). Criminal neglect: substance abuse, juvenile justice, and the children left behind. Retrieved from http://www.casacolumbia.org/templates/Publications_Reports.aspx#r21. Published October 2004. Accessed 23 Oct 2012.

- 10.Kingree JB, Betz H. Risky sexual behavior in relation to marijuana and alcohol use among African–American, male adolescent detainees and their female partners. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;72(2):197–203. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(03)00196-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson BJ, Stein MD. A behavioral decision model testing the association of marijuana and sexual risk in young adult women. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(4):875–884. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9694-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bellis MA, Hughes K, Calafat A, et al. Sexual uses of alcohol and drugs and the associated health risks: a cross sectional study of young people in nine European cities. BMC Publ Health. 2008;8:155. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bryan SD, Schmiege SJ, Magnan RE. Marijuana use and risky sexual behavior among high-risk adolescents: trajectories, risk factors, and event-level relationships. Dev Psychol. 2012;48:1429–1442. doi: 10.1037/a0027547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bryan AD, Schmiege SJ, Broaddus MR. HIV risk reduction among detained adolescents: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):e1180–e1188. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Leary A, Hatzenbuehler M. Alcohol and AIDS. 3. New York: Macmillian Reference; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raj A, Reed E, Santana MC, et al. The associations of binge alcohol use with HIV/STI risk and diagnosis among heterosexual African–American men. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;101(1–2):101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmiege SJ, Broaddus MR, Levin M, Bryan AD. Randomized trial of group interventions to reduce HIV/STD risk and change theoretical mediators among detained adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(1):38–50. doi: 10.1037/a0014513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosengard C, Stein LA, Barnett NP, et al. Randomized clinical trial of motivational enhancement of substance use treatment among incarcerated adolescents: post-release condom non-use. J HIV AIDS Prev Child Youth. 2008;8(2):45–64. doi: 10.1300/J499v08n02_04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Werch C, Moore MJ, Bian H, et al. Are effects from a brief multiple behavior intervention for college students sustained over time? Prev Med. 2011;50(1–2):30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feldstein Ewing SW, McEachern AD, Yezhuvath U, Bryan AD, Hutchison KE, Filbey FM. Integrating brain and behavior: evaluating adolescents' response to a cannabis intervention. Psychol Addict Behav. 2012 doi:10.1037/a0029767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Feldstein Ewing SW, Filbey FM, Sabbineni A, Chandler LD, Hutchison KE. How psychosocial alcohol interventions work: a preliminary look at what fMRI can tell us. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35(4):643–651. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01382.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feldstein SW, Ginsburg JI. Motivational interviewing with dually diagnosed adolescents in juvenile justice settings. Brief Treat Crisis. 2006;6(3):218–233. doi: 10.1093/brief-treatment/mhl003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monti PM, Barnett NP, O’Leary TA, Colby SM. Motivational enhancement for alcohol-involved adolescents. In: Monti PM, Barnett NP, O’Leary TA, Colby SM, editors. Adolescents, alcohol, and substance abuse: Reaching teens through brief interventions. New York: The Guilford Press; 2001. pp. 145–182. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marlatt GA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, et al. Screening and brief intervention for high-risk college student drinkers: results from a 2-year follow-up assessment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66(4):604–615. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carey MP, Lewis BP. Motivational strategies can enhance HIV risk reduction programs. AIDS Behav. 1999;3(4):269–276. doi: 10.1023/A:1025429216459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Picciano JF, Roffman RA, Kalichman SC, Rutledge SE, Berghuis JP. A telephone based brief intervention using motivational enhancement to facilitate HIV risk reduction among MSM: a pilot study. AIDS Behav. 2001;5(3):251–262. doi: 10.1023/A:1011392610578. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naar-King S, Wright K, Parsons JT, et al. Healthy choices: motivational enhancement therapy for health risk behaviors in HIV-positive youth. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18(1):1–11. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Witkiewitz K, Marlatt GA, Walker D. Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for alcohol and substance use disorders. J Cogn Psychother. 2005;19(3):211–228. doi: 10.1891/jcop.2005.19.3.211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oberle E, Schonert-Reich KA, Lawlor MS, Thomson KC. Mindfulness and inhibitory control in early adolescence. J Early Adolesc. 2012;32(4):565–588. doi: 10.1177/0272431611403741. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weinstein ND. Testing four competing theories of health-protective behavior. Health Psychol. 1993;12(4):324–333. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.12.4.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noar SM, Zimmerman RS. Health Behavior Theory and cumulative knowledge regarding health behaviors: are we moving in the right direction? Health Edu Res. 2005;20(3):275–290. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Godin G, Kok G. The theory of planned behavior: a review of its applications to health-related behaviors. Am J Health Promot. 1996;11(2):87–98. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-11.2.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Albarracin D, Johnson BT, Fishbein M, Muellerleile PA. Theories of reasoned action and planned behavior as models of condom use: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2001;127(1):142–162. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Armitage CJ, Conner M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: a meta analytic review. Br J Soc Psychol. 2001;40(4):471–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shadish W, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmiege SJ, Levin ME, Bryan AD. Regression mixture models of alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among criminally-involved adolescents. Prev Sci. 2009;10(4):335–344. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0135-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zuckerman M. Zuckerman-Kuhlman personality questionnaire (ZKPQ): An alternative five-factorial model. In: Perugini M, DeRaad B, editors. Big Give Assessment. Seattle: Hogrefe and Huber; 2002. p. 377. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bryan AD, Rocheleau CA, Robbins RN, Hutchison KE. Condom use among high-risk adolescents: testing the influence of alcohol use on the relationship of cognitive correlates of behavior. Health Psychol. 2005;24(2):133–142. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. J Stud Alcohol. 1989;50(1):30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allen JP, Litten RZ, Fertig JB, Babor T. A review of research on the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21(4):613–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1997.tb03811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chung T, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Monti PM. Alcohol use disorders identification test: factor structure in an adolescent emergency department sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26(2):223–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2002.tb02528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stephens RS, Roffman RA, Curtin L. Comparison of extended versus brief treatments for marijuana use. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(5):898–908. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.5.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Magnan RE, Callahan TJ. Ladd BO, Karoly HO, Claus ED, Bryan AD. Project SHARP: baseline findings from a randomized controlled trial of justice-involved youth. 2012. Manuscript under review.

- 45.Napper LE, Fisher DG, Reynolds GL, Johnson ME. HIV risk behavior self-report reliability at different recall periods. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(1):152–161. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9575-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vanable PA, Carey MP, Brown JL, et al. Test–retest reliability of self-reported HIV/std-related measures among African–American adolescents in four us cities. J Adol Health. 2009;44(3):214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McFarlane M, St Lawrence JS. Adolescents’ recall of sexual behavior: consistency of self-report and effect of variations in recall duration. J Adol Health. 1999;25(3):199–206. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(98)00156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler MC. Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice and Research. 2. San Francisco: Josey-Bass; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tubman JG, Langer LM. About last night: the social ecology of sexual behavior relative to alcohol use among adolescents and young adults in substance abuse treatment. J Subst Abuse. 1995;7(4):449–461. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(95)90015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hensel DJ, Stupiansky NW, Orr DP, Fortenberry JD. Event-level marijuana use, alcohol use, and condom use among adolescent women. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(3):239–243. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181f422ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.LaBrie JW, Quinlan T, Schiffman JE, Earleywine ME. Performance of alcohol and safer sex change rulers compared with readiness to change questionnaires. Psychol Addict Behav. 2005;19(1):112–115. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.MacKellar DA, Valleroy LA, Hoffmann JP, et al. Gender differences in sexual behaviors and factors associated with nonuse of condoms among homeless and runaway youths. AIDS Educ Prev. 2000;12(6):477–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yuan KH, Bentler PM. Three likelihood-based methods for mean and covariance structure analysis with nonnormal missing data. Sociol Methodol. 2000;30(1):165–200. doi: 10.1111/0081-1750.00078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bryan AD, Schmiege SJ, Broaddus MR. Mediational analysis in HIV/AIDS research: estimating multivariate path analytic models in a structural equation modeling framework. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(3):365–383. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bentler PM. EQS – Structural Equations Program Manual. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software, Inc,1995.

- 56.Williams RJ, Nowatzki N. Validity of adolescent self-report of substance use. Subst Use Misuse. 2005;40(3):299–311. doi: 10.1081/JA-200049327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Steinberg L. A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Dev Rev. 2008;28(1):78–106. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Claus E, Hutchison K. Neural mechanisms of risk taking and relationships with hazardous drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36(6):408–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ajzen I, Madden TJ. Prediction of goal-directed behavior: attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1986;22(5):453–474. doi: 10.1016/0022-1031(86)90045-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brafford LJ, Beck KH. Development and validation of a condom self-efficacy scale for college students. J Am Coll Health. 1991;39(5):219–225. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1991.9936238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brien TM, Thombs DL, Mahoney CA, Wallnau L. Dimensions of self-efficacy among three distinct groups of condom Users. J Am Coll Health. 1994;42(4):167–174. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1994.9939665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bryan AD, Aiken LS, West SG. HIV/STD risk among incarcerated adolescents: optimism about the future and self-Esteem as predictors of condom use self-efficacy. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2004;34(5):912–936. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02577.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC 225 kb)