Abstract

Background. Improved vaccination strategies against tuberculosis are needed, such as approaches to boost immunity induced by the current vaccine, BCG. Design of these strategies has been hampered by a lack of knowledge of the kinetics of the human host response induced by neonatal BCG vaccination. Furthermore, the functional and phenotypic attributes of BCG-induced long-lived memory T-cell responses remain unclear.

Methods. We assessed the longitudinal CD4+ T-cell response following BCG vaccination of human newborns. The kinetics, function, and phenotype of these cells were measured using flow cytometric whole-blood assays.

Results. We showed that the BCG-specific CD4+ T-cell response peaked 6–10 weeks after vaccination and gradually waned over the first year of life. Highly activated T-helper 1 cells, predominantly expressing interferon γ, tumor necrosis factor α, and/or interleukin 2, were present at the peak response. Following contraction, BCG-specific CD4+ T cells expressed high levels of Bcl-2 and displayed a predominant CD45RA–CCR7+ central memory phenotype. However, cytokine and cytotoxic marker expression by these cells was more characteristic of effector memory cells.

Conclusions. Our findings suggest that boosting of BCG-primed CD4+ T cells with heterologous tuberculosis vaccines may be best after 14 weeks of age, once an established memory response has developed.

Keywords: Bacille Calmette-Guérin, Vaccination, Newborns, Memory T cells, T cell kinetics

Recent estimates of the global tuberculosis burden indicate reductions in the number of persons with tuberculosis, the incidence of tuberculosis, and deaths due to tuberculosis [1]. Despite this, approximately 8.8 million new tuberculosis cases were diagnosed in 2010; 1.45 million individuals died from tuberculosis [1]. BCG vaccination in infancy is routine in tuberculosis-endemic countries. However, BCG confers reliable protection against severe forms of tuberculosis in infancy only [2]. Protection against pulmonary disease at all ages is variable and mostly poor. Epidemiological modeling suggests that a new tuberculosis vaccine or vaccination strategy that has greater protective efficacy than the current BCG strategy is critical for tuberculosis elimination [3].

Most investigators agree that future vaccination against tuberculosis would involve a heterologous prime-boost regimen, with BCG or an improved live mycobacterial vaccine as a prime, followed by an adjuvanted subunit or viral vectored boost [4, 5]. A major hurdle to designing novel vaccination strategies is our limited knowledge of key T-cell response characteristics induced by BCG.

The kinetics of T cells induced by neonatal BCG vaccination have not been studied in humans; in particular, we do not know when this immune response peaks. This is a critical knowledge gap, because studies of CD8+ [6, 7] and CD4+ [8, 9] responses in viral infection models suggest that the best time for boosting is after the peak effector phase, when effector T cells have transitioned into an established memory population. Vaccine boosting during the primary effector phase, when cells are activated, may lead to T-cell exhaustion or activation-induced cell death [6, 9, 10].

Another unresolved question is whether BCG vaccination consistently induces long-lived central memory cells. Cross-sectional studies in infants have suggested that BCG may induce primarily effector T cells [11–13]. This is supported by studies of murine BCG vaccination, which induces a predominant effector T-cell response that fails to establish a long-lived central memory response [14, 15]. These data led to the hypothesis that the short-lived nature of BCG-induced effector T cells underlies the limited duration of BCG-induced protection against tuberculosis [15]. However, BCG vaccination of infants and adults induces immunological memory [16–18], and a recent retrospective analysis of long-term efficacy of BCG given between 1935–1938 suggests that BCG induces long-lived protection [19].

A comprehensive longitudinal study of memory phenotype following human newborn BCG vaccination, particularly a study that yields clarity about the induction of central memory T cells, is required. Therefore, we characterized the kinetics, function, and phenotype of BCG-specific T cells in a longitudinal study of infants routinely vaccinated with BCG at birth. Expansion and contraction of the primary BCG-specific T-cell response occurred within 3 months of vaccination, and the magnitude of specific CD4+ T cells peaked 6–10 weeks after vaccination. After peak, BCG-specific CD4+ T cells displayed a phenotype of classic central memory T cells but retained functional characteristics more consistent with effector T cells.

METHODS

Study Participants and Blood Collection

We conducted a longitudinal observational study in healthy infants. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the University of Cape Town Research Ethics Committee and by the Western Cape Department of Health. Mothers attending maternity units in the Worcester district, 110 km from Cape Town, South Africa, were approached and gave written informed consent. Only mothers who had undergone screening for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection by the state-run program to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV and who were HIV negative were recruited. Infants, who received routine intradermal BCG vaccine (Danish strain 1331; Statens Serum Institut) within 48 hours of birth were followed up to 52 weeks of age. Peripheral venous blood was collected from each infant at three or four time points, corresponding to the following 7 ages: 3, 6, 10, 14, 27, 40, or 52 weeks. Allocation of infants was designed to enroll a minimum of 33 infants at each time point.

Antigens and Antibodies Used in Assays

The following antigens were used: BCG (Danish strain 1331), Mycobacterium tuberculosis purified protein derivative, tetanus toxoid (TT; control vaccine antigen), ESAT6/CFP10 fusion protein, phytohemagglutinin (positive control), phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, ionomycin and costimulatory antibodies, anti-CD28, and anti-CD49d.

The following monoclonal antibodies were used for flow cytometry: CD3, CD4, CD8, Ki67, Bcl-2, CD38, HLA-DR, CD45RA, CCR7, granulysin, granzyme B, perforin, interferon γ (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin 2 (IL-2), and interleukin 17 (IL-17). Fluorochrome and antibody clone details are available in the Supplementary Methods.

Whole-Blood Intracellular Cytokine Staining (WB-ICS) Assay

Heparinized whole blood was processed immediately after collection. The WB-ICS assay [20] and whole-blood Ki67 proliferation assay [12] were performed as previously described. Detailed procedures are available in the Supplementary Methods.

Cytotoxic Molecule Expression Assay

Whole blood (125 μL diluted 1:5 in warm Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium) was incubated with antigens at 37°C in 5% CO2. On day 3, samples were incubated with BD FACS Lysing Solution to lyse red cells and fix white cells. White blood cells were cryopreserved in 10% dimethyl sulfoxide/fetal calf serum. Flow cytometric analysis was later performed as described above.

Data Analysis

Outcomes assessed both cross-sectionally (at each age) and longitudinally included BCG-specific T-cell frequencies defined by cytokine production, phenotype of these cells, frequency and phenotype of proliferating (Ki67+) T cells, and frequency of specific (Ki67+) T cells expressing cytotoxic markers.

Infants who acquired M. tuberculosis infection or who received a diagnosis of active tuberculosis during the study were excluded from analysis. M. tuberculosis infection was determined at each time point by measuring T-cell proliferation following 6-day culture with ESAT6/CFP10 fusion protein [21].

Data analysis details for flow cytometry outcomes are available in the Supplementary Methods.

GraphPad Prism, version 5, was used for data presentation and statistical analyses. Mann–Whitney or Wilcoxon signed rank tests were used to compare different time points or groups. The Spearman nonparametric correlation test was used to test for associations. P values of < .05 were considered statistically significant. To account for multiple testing, the Bonferroni adjustment was applied when necessary. Adjusted P values considered to be significant are given in the respective figure legends.

RESULTS

Participants

Ninety infants were enrolled. Analyses were restricted to 73 infants; 6 infants did not meet clinical inclusion criteria, and 11 were lost to follow-up (Table 1). All infants received BCG within 48 hours of birth, as well as the full complement of childhood vaccines of the South African Expanded Program on Immunization [22].

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics Among All Infants and Exclusion Criteria and Reasons for Loss to Follow-up Among Infants Excluded From the Final Analysis

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Demographic characteristic (n = 90) | |

| Sex | |

| Male | 43 |

| Female | 47 |

| Gestational age, weeks | |

| Mean±SDa | 38.6±1.8 |

| Not recorded | 1 |

| Reason for exclusion (n = 6) | |

| Unsuccessful blood collection at 2 consecutive time points | 2 |

| Initiation of tuberculosis treatment | 1 |

| Exposure to a household contact with active tuberculosis | 2 |

| M. tuberculosis infectionb | 1 |

| Reason for loss to follow-up (n = 11) | |

| Parents/guardians withdrew infant from study | 8 |

| Moved with no forwarding address | 3 |

Data are no. (%) of infants, unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviation: M. tuberculosis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

a Gestational ages of some infants were recorded as “term.” These ages were assigned a value of 40 weeks.

b Determined by measuring T-cell proliferation in response to ESAT6/CFP10 fusion protein, following a 6-day culture.

Kinetics of the BCG-Specific T-Helper 1 (Th1) Response

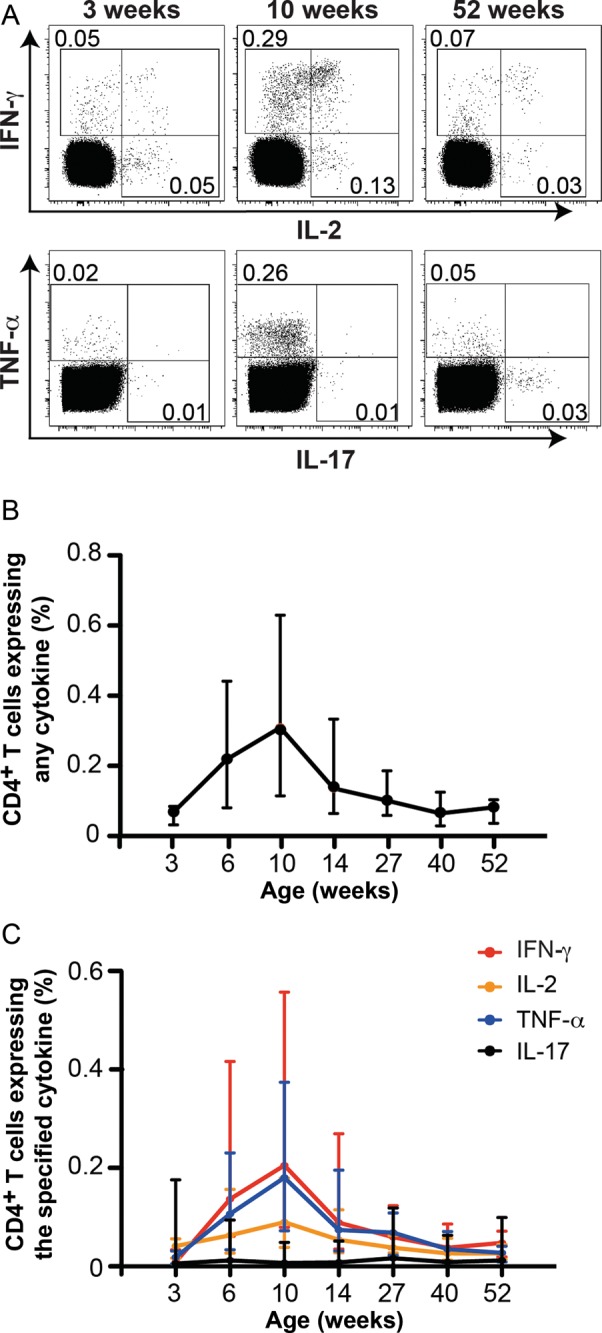

We measured the magnitude and kinetics of the BCG-induced response by using flow cytometry to quantify CD4+ T cells expressing IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, and/or IL-17 (Supplementary Figure 1A and 1B). BCG-specific CD4+ T-cell responses were observed in all infants investigated 3 weeks after vaccination (Figure 1). Frequencies of specific CD4+ T cells peaked at the 10-week time point after vaccination and gradually waned until the 40-week time point (Figure 1B). By 1 year, the magnitude of these cytokine-expressing CD4+ T cells had returned to levels similar to those observed at 3 weeks (Figure 1B). Similar response kinetics were observed when frequencies of IFN-γ–, TNF-α–, or IL-2–expressing BCG-specific CD4+ T cells were analyzed individually (Figure 1C). By contrast, in most infants, specific IL-17–expressing CD4+ T-cell frequencies were similar to those of unstimulated controls at all post-BCG time points. We previously reported that virtually no specific CD4+ T cells could be detected with this assay at 10 weeks of age when BCG was not given [11].

Figure 1.

Longitudinal changes in BCG-specific CD4+ T-cell cytokine responses during the first year of life. Intracellular cytokine expression by CD4+ T cells was measured by intracellular cytokine staining, following stimulation of whole blood for 12 hours with BCG. Brefeldin A was added for the last 5 hours of stimulation. Detailed procedures are available in the Supplementary Methods. A, Flow cytometric plots from a representative infant showing changes in interferon γ (IFN-γ), interleukin 2 (IL-2), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), and/or interleukin 17 (IL-17) expression by BCG-specific CD4+ T cells 3, 10, and 52 weeks after BCG vaccination. The flow cytometric gating strategy is shown in Supplementary Figure 1. Numbers in the flow cytometry plots represent the proportions of CD4+ T cells in each gate. B and C, Kinetic changes in frequencies of total cytokine-expressing BCG-specific CD4+ T cells (B) and BCG-specific CD4+ T cells expressing either IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α, or IL-17 (C). The line represents the median, and error bars represent the interquartile range.

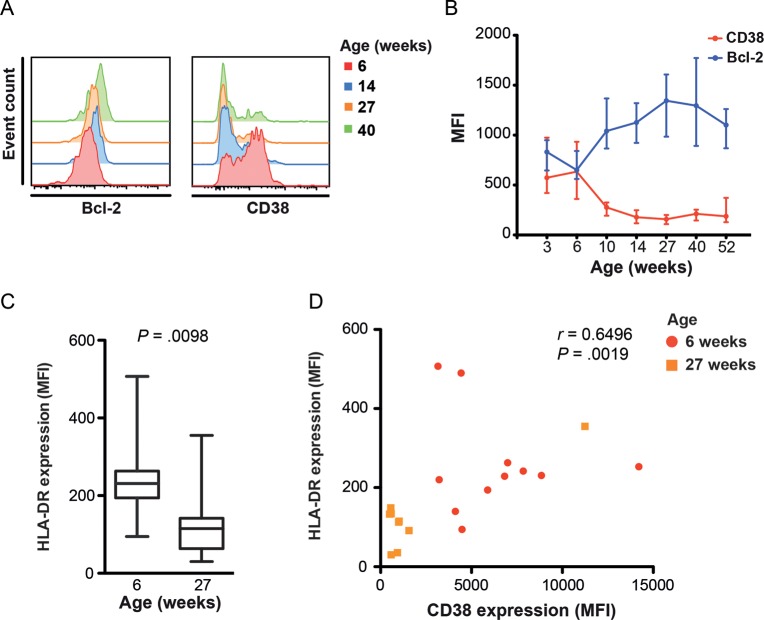

CD38 and Bcl-2 Expression by BCG-Specific CD4+ T Cells

To characterize changes in the long-lived potential and activation status of BCG-specific Th1 cells, we measured expression of the antiapoptotic marker Bcl-2 and the activation marker CD38 by total cytokine-expressing CD4+ T cells (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 2A–D).

Figure 2.

Longitudinal changes in BCG-specific T-cell expression of antiapoptotic and activation markers during the first year of life. Expression of Bcl-2, CD38, and HLA-DR by cytokine-expressing BCG-specific CD4+ T cells was measured by whole-blood intracellular cytokine staining and flow cytometry. A, Histograms from a representative individual infant showing changes in Bcl-2 and CD38 expression levels in total cytokine-expressing BCG-specific CD4+ T cells (combined interferon γ [IFN-γ], interleukin 2 [IL-2], tumor necrosis factor α [TNF-α], and/or interleukin 17 [IL-17] expression). B, Changes in Bcl-2 and CD38 expression levels, represented as median fluorescence intensity (MFI), by BCG-specific CD4+ T cells. The line represents the median, and error bars represent the interquartile range. C, HLA-DR expression levels, represented as MFI, by BCG-specific CD4+ T cells at 6 and 27 weeks after vaccination. The horizontal line represents the median, the box represents the interquartile range, and the whiskers represent the range. Because HLA-DR expression was only measured at 6 and 27 weeks of age, no Bonferroni adjustment was applied to this comparison. D, Association between HLA-DR and CD38 expression levels by cytokine-expressing CD4+ T cells 6 and 27 weeks after vaccination. The strength of the correlation was calculated using the Spearman rank correlation test.

BCG-specific CD4+ T cells expressed low levels of Bcl-2 (Bcl-2low) and high levels of CD38 (CD38high) 3–6 weeks after vaccination, before the peak Th1 response (Figure 2A and 2B), a phenotype characteristic of activated effector T cells. T-cell activation waned rapidly thereafter. Compared with the 6 week time point, CD38 expression had decreased at 10 weeks (P = .0011). Activation status of BCG-specific CD4+ T cells declined up to 14 weeks but thereafter remained stable up to 1 year. This decrease in T-cell activation was mirrored by an increase in Bcl-2 expression up to 27 weeks, when the level of Bcl-2 expression peaked (6 vs 10 weeks [P < .0001]; Figure 2B).

Since CD38 is highly expressed on naive T cells in infants [23], we sought to confirm that CD38 was an appropriate activation marker of antigen-specific T cells. We measured expression of the T-cell activation marker HLA-DR by BCG-specific, cytokine-expressing T cells at 6 and 27 weeks. Consistent with CD38, HLA-DR expression was lower at 27 weeks, compared with 6 weeks (P = .0098; Figure 2C); HLA-DR and CD38 expression levels correlated directly (Figure 2D). Cytokine-expressing CD4+ T cells were also virtually exclusive to CD45RA–, antigen-experienced T cells (discussed below in the “Memory Phenotype” subsection of Results), excluding confounding effects by CD38high naive T cells from our measurements. This suggests that upregulation of CD38 expression by BCG-specific CD4+ T cells was antigen specific.

Our data suggest that BCG-specific cytokine-expressing T cells are activated and may be susceptible to apoptosis during the first 6 weeks after BCG vaccination.

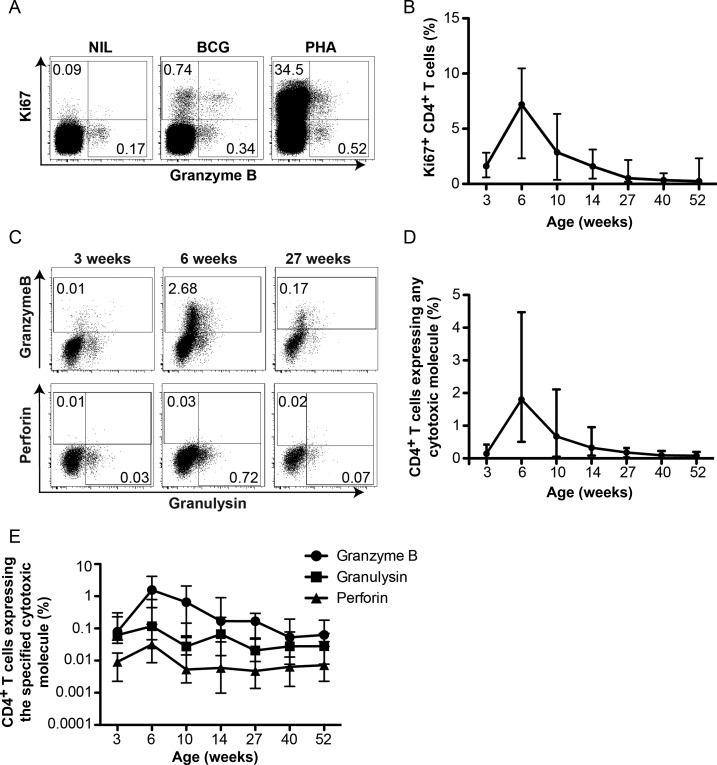

Kinetics of BCG-Specific CD4+ T Cells Expressing Cytotoxic Molecules

Mycobacteria-specific CD4+ T cells with cytotoxic function have been described in adults [24]. To further characterize BCG-induced T cells, we assessed BCG-specific CD4+ T-cell expression of granzyme B, perforin, and granulysin. Detection of de novo cytotoxic molecule expression is challenging because these molecules reside at high levels in preformed cytotoxic granules, which degranulate immediately upon antigen stimulation [25]. To circumvent this, we incubated whole blood with BCG for 3 days and detected T-cell upregulation of Ki67. This allowed measurement of cytotoxic molecules expressed in vitro by BCG-specific CD4+ T cells identified as Ki67+, as described elsewhere [26] (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Longitudinal changes in Ki67 expression and intracellular cytotoxic molecule expression in BCG-specific CD4+ T cells during the first year of life. Expression of intracellular Ki67, granzyme B, perforin, and granulysin was measured by flow cytometry after stimulation of whole blood with BCG for 3 days. Detailed procedures are available in the Supplementary Methods. A, Flow cytometric plots from a representative individual infant showing Ki67 expression by CD4+ T cells. B, Frequencies of Ki67 expressing CD4+ T cells over the first year of life. Numbers in the flow cytometry plots represent the proportions of CD4+ T cells in each gate. C, Flow cytometric plots showing changes in intracellular granzyme B, perforin, and granulysin expression upon BCG stimulation by CD4+ T cells. D, Kinetic changes in total cytotoxic molecule expression (granzyme B, perforin, and/or granulysin) by BCG-specific (Ki67+) CD4+ T cells. E, Kinetic changes in BCG-specific (Ki67+) CD4+ T cells expressing granzyme B, granulysin, or perforin over the first year of life. Lines represent the median, and error bars represent the interquartile range.

Low Ki67+ BCG-specific CD4+ T-cell frequencies were detected 3 weeks after BCG vaccination (Figure 3B). The BCG-specific CD4+ T-cell response expanded to a peak at 6 weeks (P = .0007) and gradually contracted during follow-up to levels below the 3-week response (Figure 3B).

Next, we measured granzyme B, perforin, and granulysin expression by Ki67+ BCG-specific T cells (Figure 3C and Supplementary Figure 3A and 3B). The kinetics of total cytotoxic marker–expressing BCG-specific CD4+ T cells matched the kinetics of Ki67+ CD4+ T cells; cytotoxic marker–expressing CD4+ T cell frequencies peaked at 6 weeks and gradually waned up to 1 year (Figure 3C and 3D). Granzyme B was the predominant cytotoxic marker expressed by BCG-specific CD4+ T cells, particularly during the peak; granzyme B expression is characteristic of effector T cells [27]. Specific CD4+ T cells also expressed granulysin and low levels of perforin (Figure 3E).

These data show that BCG-specific cytotoxic CD4+ T cells peak at the 6-week time point and thereafter gradually wane over the first year of life.

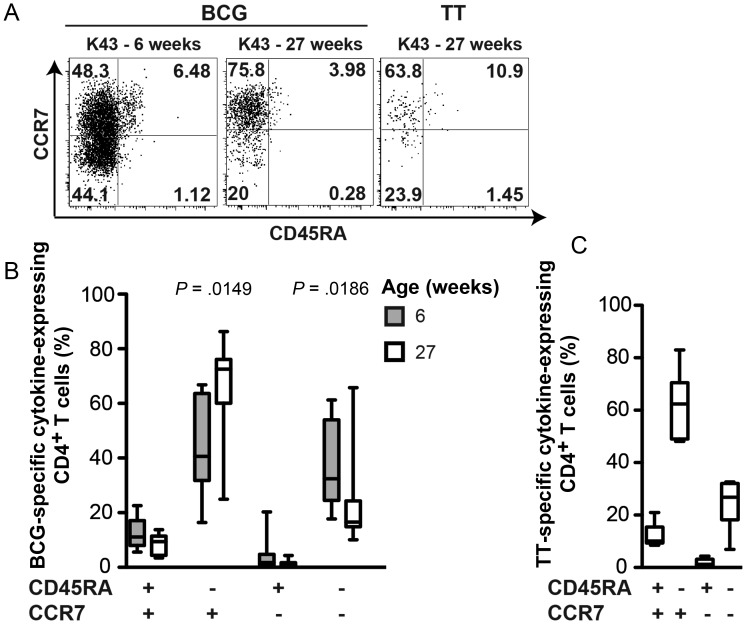

Memory Phenotype of BCG-Specific CD4+ T Cells

Our finding that BCG-specific CD4+ T cells switch to a Bcl-2highCD38low phenotype after the peak effector phase (Figures 1–3) suggests that BCG-induced CD4+ T cells may develop long-lived memory characteristics. We therefore sought to determine whether contraction of the response coincided with functional changes consistent with memory development, such as greater IL-2 expression and lesser IFN-γ expression [28], and with upregulation of CCR7, a classic central memory marker [29].

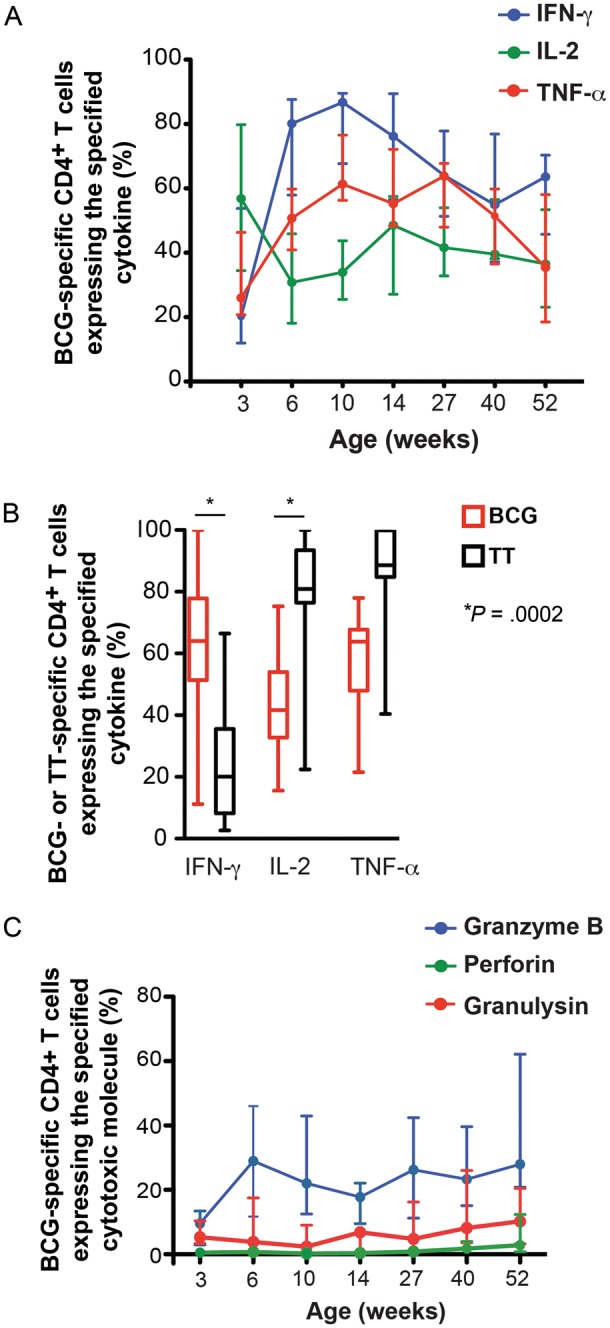

During the peak response 6–10 weeks after vaccination, BCG-specific CD4+ T cells preferentially expressed IFN-γ and not IL-2 (Figure 4A), a typical effector cell cytokine profile [29]. Contraction of the specific CD4+ T-cell response 10 weeks after vaccination coincided with a decrease in the proportion of IFN-γ–expressing cells. However, no concomitant increase (or decrease) in the proportion of IL-2–expressing CD4+ T cells was observed during this response phase (Figure 4A). The proportion of TNF-α–expressing specific CD4+ T cells consistently increased throughout the first year.

Figure 4.

Qualitative changes in BCG-specific T cell responses during the first year of life. A, Relative proportions of BCG-specific CD4+ T cells expressing interferon γ (IFN-γ), interleukin 2 (IL-2), or tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) out of the total cytokine-expressing CD4+ T-cell response. B, Comparison of the relative proportions of cells expressing IFN-γ, IL-2, or TNF-α among BCG-specific CD4+ T cells and tetanus toxoid (TT)–specific CD4+ T cells at 27 weeks of age. This time point corresponds to 27 weeks after BCG vaccination and 13 weeks after TT vaccination. The horizontal line represents the median, the box represents the interquartile range, and the whiskers represent the range. Groups were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. An adjusted P value of <.0167 (0.05 divided by 3) was considered significant. C, Relative proportions of BCG-specific CD4+ T cells expressing granzyme B, perforin, or granulysin out of the total cytotoxic molecule–expressing CD4+ T-cell response. Lines represent the median, and error bars represent the interquartile range.

To further interpret these cytokine expression patterns, we compared the proportions of cytokine-expressing BCG- and TT-specific CD4+ T cells at 27 weeks of age (27 weeks after BCG vaccination and 13 weeks after TT vaccination). Since the TT protein vaccine is efficiently and rapidly cleared, TT-specific T cells provide a model of evolution into a central memory response [28]. As expected, the TT-specific CD4+ T-cell memory response was characterized by low proportions of IFN-γ and by high proportions of IL-2– and TNF-α–expressing cells. By comparison, BCG-specific CD4+ T cells expressed higher proportions of IFN-γ (P = .0002) and lower proportions of IL-2 (P = .0002; Figure 4B).

These data suggest limited evolution of the BCG-induced response into classical central memory cells, as defined in models of acute and chronic viral infections. This was further supported by qualitative analysis of cytotoxic molecule expression. Granzyme B expression, also characteristic of an effector response, characterized the dominant cytotoxic CD4+ T-cell subset throughout the first year (Figure 4C).

CD45RA and CCR7 expression on antigen-experienced T cells have been used to infer memory phenotype [29]. CCR7 expression endows antigen-experienced CD45RA– T cells with the potential for lymph node homing, which is characteristic of long-lived central memory cells. Establishment of such a long-lived memory response is typically observed following successful clearance of acute infections or vaccine antigens [28, 30]. By contrast, absence of CCR7 expression allows cells to migrate to the site of infection, a characteristic of short-lived effector cells observed in persistent viral infections [31]. We measured CD45RA and CCR7 expression during the peak BCG-induced CD4+ T-cell response, 6 weeks after vaccination, and again after the contraction phase, 27 weeks after vaccination. Surprisingly, a large proportion of BCG-specific cytokine-expressing T cells displayed a CD45RA–CCR7+ central memory phenotype, even 6 weeks after vaccination (Figure 5A and 5B). CCR7 expression by specific CD4+ T cells was even higher after the contraction phase, 27 weeks after vaccination, when the BCG-specific response had developed into a classic CD45RA–CCR7+ central memory response (Figure 5A and 5B). This was consistent with the central memory phenotype displayed by TT-specific CD4+ T cells at 27 weeks (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Memory phenotype of BCG-specific and tetanus toxoid (TT)–specific CD4+ T cells. A, Flow cytometric plots from a representative individual infant showing expression patterns of CCR7 and CD45RA by T-helper 1 (Th1) cytokine–expressing CD4+ T cells (combined interferon γ [IFN-γ], interleukin 2 [IL-2], and/or tumor necrosis factor α [TNF-α] expression), following stimulation of whole blood with either BCG or TT at the indicated ages. Cytokine-expressing CD4+ T cells were overlaid onto a density plot of the total CD4+ T-cell population. Numbers represent the proportion of cytokine-expressing CD4+ T cells in each quadrant. B, Memory phenotype of BCG-specific total cytokine-expressing CD4+ T cells 6 and 27 weeks after BCG vaccination. Groups were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. An adjusted P value of <.0125 (0.05 divided by 4) was considered significant. C, Memory phenotype of TT-specific total cytokine-expressing CD4+ T cells 27 weeks after BCG vaccination and 13 weeks after TT vaccination. The horizontal line represents the median, the box represents the interquartile range, and the whiskers represent the range.

Therefore, although cytokine and cytotoxic marker expression did not suggest evolution of BCG-specific T cells into a central memory response over the first year of life, surface marker expression did support transition into this phenotype.

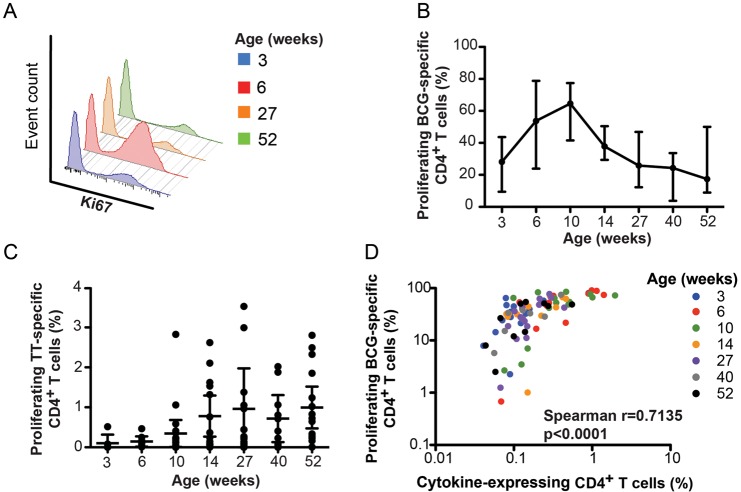

In Vitro Proliferation of BCG-Specific T Cells

To address the apparent dichotomy of functional and surface characteristics of the specific response, we measured in vitro proliferation of BCG-specific CD4+ T cells, using a previously optimized Ki67 expression assay [26]. BCG-specific CD4+ T cell proliferation peaked 10 weeks after vaccination and gradually waned over the first year of life (Figure 6A and 6B). At 27 weeks after vaccination, the proliferative potential of BCG-specific CD4+ T cells had returned to levels similar to those observed at 3 weeks (Figure 6B). By contrast, the TT-specific proliferative potential showed no sign of waning at any time point after infants received the last TT vaccine boost, at 14 weeks of age (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Longitudinal changes in BCG-specific in vitro proliferation during the first year of life. A, Histograms from a representative individual infant showing changes in BCG-specific CD4+ T-cell proliferation (measured as Ki67 expression) over time. Ki67 expression was measured after in vitro stimulation of whole blood for 6 days with BCG or tetanus toxoid (TT). Detailed procedures are available in the Supplementary Methods. B, Changes in BCG-specific CD4+ T-cell proliferation over the first year of life. The line represents the median, and error bars represent the interquartile range. C, Changes in TT-specific CD4+ T-cell proliferation over the first year of life. Dots represent individual infants, the horizontal line represents the median, and the whiskers represent the interquartile range. D, Association between the frequency of total cytokine-expressing BCG-specific CD4+ T cells, measured by intracellular cytokine staining assay, and the frequency of proliferating (Ki67+) BCG-specific CD4+ T cells. Data from all time points were included; time points are indicated in the legend. The correlation was calculated using the Spearman rank correlation test.

Finally, we sought to determine whether the waning BCG-specific proliferative response during follow-up was associated with frequencies of BCG-specific precursor CD4+ T cells detected ex vivo. Frequencies of BCG-specific cytokine-expressing CD4+ T cells correlated with frequencies of proliferating CD4+ T cells (Figure 6D). Since IL-2 is critical for maintenance and proliferation of memory T-cell populations [32], we also examined the relationship between IL-2–expressing T-cell frequencies and proliferating BCG-specific CD4+ T cells. No correlation was observed between these BCG-specific functions (data not shown).

We concluded that the loss of BCG-specific T-cell proliferative potential is directly linked to CD4+ T-cell precursor frequency and does not reflect the composition of BCG-specific memory cells.

DISCUSSION

We characterized the function and phenotype of BCG-specific T-cell responses following newborn BCG vaccination. We showed the following: (1) the BCG-induced CD4+ T-cell response peaked 6–10 weeks after vaccination and thereafter gradually waned; (2) the primary response was characterized by highly activated Th1 cells, producing IFN-γ predominantly and expressing low levels of Bcl-2; and (3) following the contraction phase of the response, BCG-specific CD4+ T cells assumed a central memory phenotype but shared functional features of effector memory T cells.

We propose that boosting of the BCG-primed response with a heterologous vaccine would be most optimal after establishment of a memory T-cell population. This population would have a central memory phenotype, express high levels of Bcl-2, and be CD38low [6, 28, 30, 33]. Survival of memory T cells following contraction is mediated in part by antiapoptotic molecules, such as Bcl-2 [10, 27, 34]. By contrast, highly activated effector T cells, such as those observed 6–10 weeks after vaccination, may be more susceptible to activation-induced cell death [33, 35, 36]. Boosting T-cell responses during the effector phase of the response may lead to T-cell exhaustion and death, drive generation of predominantly short-lived effector cells, lead to the expansion of highly differentiated T cells, or limit T-cell clonal expansion [8, 32, 37]. Our data suggest that the ideal time for boosting is at 14 weeks or thereafter, following the contraction of the peak effector response. We recently showed successful boosting of BCG-induced CD4+ T cells with the novel tuberculosis vaccine MVA85A at 5–12 months of age [38]. Timing of booster vaccines should also consider other factors. It may be easier to ensure adherence and, therefore, vaccination coverage if new vaccines are coadministered as a part of the activities of World Health Organization Routine Expanded Programme on Immunisation. However, co-administration could lead to interference, as recently reported when MVA85A was co-administered [39].

We found that BCG-specific CD4+ T cells displayed attributes consistent with long-lived central memory cells, while cytokine and cytotoxic marker functional attributes were more characteristic of effector cells. Studies of 3 highly effective human vaccines, against tetanus, yellow fever, and smallpox, showed that stable long-lived memory T cells can protect for decades [28, 30]. It is not known whether such a central memory response is required for protective immunity against tuberculosis. BCG affords protection against disseminated forms of tuberculosis only in infants and young children [40, 41]. The short-lived duration of protection has been attributed to failure of BCG to induce long-lived memory cells or to a gradual loss of BCG-specific T cells [14, 15]. Our finding that BCG-specific CD4+ T cells express high levels of Bcl-2 and CCR7 are at odds with this hypothesis. Furthermore, a recent retrospective analysis of previous participants in a placebo-controlled efficacy trial of BCG during 1935–1938 showed evidence of long-term BCG-mediated protection [19]. Regardless, studies are needed to determine which phenotypic and/or functional attributes of the BCG-specific response may be associated with long-lived protection.

Our finding that BCG-specific CD4+ T cells displayed characteristics of both central and effector memory T cells was surprising, given the polar distinction into either subset observed in acute and chronic viral infections [7, 42–44]. Many factors may influence development of long-lived memory T cells. Of these, antigen load and persistence may be most important [43, 45]. In humans, peripheral blood T cells displaying qualities of long-lived memory are detectable many years after primary immunization with efficiently cleared vaccines, such as TT vaccine or yellow fever vaccine [28, 30]. By contrast, excessive and/or persistent antigenic stimulation favors commitment of effector memory T cells and impairs development of long-lived memory cells [9, 43, 46, 47]. Our data of nonpolarized memory phenotype and function may reflect persistence of BCG and may suggest that programming of memory T cells after infant vaccination with live BCG may be unique. Nevertheless, the decrease in activation markers and progressive increase in Bcl-2 and CCR7 expression may also suggest that BCG is cleared within the first 3 months after vaccination [33].

Our finding that BCG-specific CD4+ T cells predominantly expressed IFN-γ is consistent with findings from previous studies [11, 12, 48]. However, the prominent central memory phenotype observed here is different from the predominant effector phenotype of BCG-specific CD4+ T cells reported previously in infants [11, 12] and children [13]. In children, these phenotypic differences may be related to persistent exposure to cross-reactive environmental mycobacteria, other bacteria, and/or M. tuberculosis, which may drive T-cell differentiation. However, this cannot explain the different memory phenotypes in infants, because exposure would have been limited during the first year of life. While assay procedures in the current study were virtually identical to those in our previous projects, we used a different anti-CCR7 monoclonal antibody clone in the current study, which may have influenced outcomes [11–13]. Regardless, since we used TT-induced CD4+ T cells as a control of central memory cells, we are confident that the memory phenotypes described here are reliable.

Our memory phenotype results are also different from the dominant effector memory phenotype reported in BCG-vaccinated mice. BCG causes a chronic infection in mice that drives persistent immune activation [49]. The persistence of replicating BCG in mice thus induces and maintains mycobacteria-specific effector memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [14, 49]. We propose that these caveats preclude useful comparison of immune responses induced by murine BCG vaccination to those in humans.

In conclusion, we showed that newborn BCG vaccination leads to development of a memory CD4+ T-cell population that possesses phenotypic characteristics of central memory cells and functional attributes of effector memory cells. The BCG-primed response may ideally be boosted with heterologous tuberculosis vaccines after 14 weeks of age. Collectively, these data provide a framework for optimizing prime-boost vaccination strategies and are useful as a comparative model for assessing T-cell responses in infants following immunization with novel tuberculosis vaccine candidates.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online (http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank the parents and guardians of infants who took part in this study.

A. P. S., W. H. B., E. J. H, T. J. S., and W. A. H. designed the study and experiments; A. P. S., M. D. K., M. M., E. J. H., and W. A. H. contributed to clinical protocol development; A. P. S., C. K. C. K. C., N. G. T. C., L. L., L. M., and E. S. performed the experiments; T. C., G. J., E. J. V. R., G. K., and B. P. performed clinical procedures; L. V. W. performed data capturing; and all authors contributed to writing and/or review of the manuscript.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Tuberculosis Research Unit, established with federal funds from the National Institutes of Health (NIH; contract HHSN266200700022C/NO1-AI-70022); the NIH (RO1-AI087915 to W. A. H.); and the Wellcome Trust (through the Clinical Infectious Disease Research Initiative).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed

References

- 1.Geneva: WHO; 2011. Global tuberculosis control. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trunz BB, Fine P, Dye C. Effect of BCG vaccination on childhood tuberculous meningitis and miliary tuberculosis worldwide: a meta-analysis and assessment of cost-effectiveness. Lancet. 2006;367:1173–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68507-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abu-Raddad LJ, Sabatelli L, Achterberg JT, et al. Epidemiological benefits of more-effective tuberculosis vaccines, drugs, and diagnostics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13980–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901720106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tuberculosis vaccine candidates. 2010 STOP tuberculosis Partnership. http://www.stoptb.org/wg/new_vaccines/documents.asp . [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hatherill M. Prospects for elimination of childhood tuberculosis: the role of new vaccines. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:851–6. doi: 10.1136/adc.2011.214494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wherry EJ, Barber DL, Kaech SM, Blattman JN, Ahmed R. Antigen-independent memory CD8 T cells do not develop during chronic viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16004–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407192101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wherry EJ, Teichgraber V, Becker TC, et al. Lineage relationship and protective immunity of memory CD8 T cell subsets. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:225–34. doi: 10.1038/ni889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jelley-Gibbs DM, Brown DM, Dibble JP, Haynes L, Eaton SM, Swain SL. Unexpected prolonged presentation of influenza antigens promotes CD4 T cell memory generation. J Exp Med. 2005;202:697–706. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jelley-Gibbs DM, Dibble JP, Filipson S, Haynes L, Kemp RA, Swain SL. Repeated stimulation of CD4 effector T cells can limit their protective function. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1101–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKinstry KK, Strutt TM, Swain SL. Regulation of CD4+ T-cell contraction during pathogen challenge. Immunol Rev. 2010;236:110–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00921.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kagina BM, Abel B, Bowmaker M, et al. Delaying BCG vaccination from birth to 10 weeks of age may result in an enhanced memory CD4 T cell response. Vaccine. 2009;27:5488–95. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.06.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soares AP, Scriba TJ, Joseph S, et al. Bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccination of human newborns induces T cells with complex cytokine and phenotypic profiles. J Immunol. 2008;180:3569–77. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tena-Coki NG, Scriba TJ, Peteni N, et al. CD4 and CD8 T-cell responses to mycobacterial antigens in African children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:120–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200912-1862OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henao-Tamayo MI, Ordway DJ, et al. Phenotypic definition of effector and memory T-lymphocyte subsets in mice chronically infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2010;17:618–25. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00368-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orme IM. The Achilles heel of BCG. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2010;90:329–32. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lalor MK, Ben-Smith A, Gorak-Stolinska P, et al. Population differences in immune responses to Bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccination in infancy. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:795–800. doi: 10.1086/597069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McShane H, Pathan AA, Sander CR, et al. Recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara expressing antigen 85A boosts BCG-primed and naturally acquired antimycobacterial immunity in humans. Nat Med. 2004;10:1240–4. doi: 10.1038/nm1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weir RE, Gorak-Stolinska P, Floyd S, et al. Persistence of the immune response induced by BCG vaccination. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aronson NE, Santosham M, Comstock GW, et al. Long-term efficacy of BCG vaccine in American Indians and Alaska Natives: A 60-year follow-up study. JAMA. 2004;291:2086–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanekom WA, Hughes J, Mavinkurve M, et al. Novel application of a whole blood intracellular cytokine detection assay to quantitate specific T-cell frequency in field studies. J Immunol Methods. 2004;291:185–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Govender L, Abel B, Hughes EJ, et al. Higher human CD4 T cell response to novel Mycobacterium tuberculosis latency associated antigens Rv2660 and Rv2659 in latent infection compared with tuberculosis disease. Vaccine. 2010;29:51–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.South African Expanded Programme on National Department of Health Immunisation. April 2009. http://www.doh.gov.za/docs/publicity/2009/childimmunisation.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shearer WT, Rosenblatt HM, Gelman RS, et al. Lymphocyte subsets in healthy children from birth through 18 years of age: the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group P1009 study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:973–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bastian M, Braun T, Bruns H, Rollinghoff M, Stenger S. Mycobacterial lipopeptides elicit CD4+ CTLs in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected humans. J Immunol. 2008;180:3436–46. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Appay V, Zaunders JJ, Papagno L, et al. Characterization of CD4(+) CTLs ex vivo. J Immunol. 2002;168:5954–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soares A, Govender L, Hughes J, et al. Novel application of Ki67 to quantify antigen-specific in vitro lymphoproliferation. J Immunol Methods. 2010;362:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaech SM, Tan JT, Wherry EJ, Konieczny BT, Surh CD, Ahmed R. Selective expression of the interleukin 7 receptor identifies effector CD8 T cells that give rise to long-lived memory cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1191–8. doi: 10.1038/ni1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cellerai C, Harari A, Vallelian F, Boyman O, Pantaleo G. Functional and phenotypic characterization of tetanus toxoid-specific human CD4(+) T cells following re-immunization. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1129–38. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Forster R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nat Immunol. 1999;14:659–60. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller JD, van der Most RG, Akondy RS, et al. Human effector and memory CD8+ T cell responses to smallpox and yellow fever vaccines. Immunity. 2008;28:710–22. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sallusto F, Geginat J, Lanzavecchia A. Central memory and effector memory T cell subsets: function, generation, and maintenance. Ann Rev Immunol. 2004;22:745–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dooms H, Wolslegel K, Lin P, Abbas AK. Interleukin-2 enhances CD4+ T cell memory by promoting the generation of IL-7R alpha-expressing cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:547–57. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McKinstry KK, Golech S, Lee WH, Huston G, Weng NP, Swain SL. Rapid default transition of CD4 T cell effectors to functional memory cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2199–211. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li J, Huston G, Swain SL. IL-7 promotes the transition of CD4 effectors to persistent memory cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1807–15. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lynch DH, Ramsdell F, Alderson MR. Fas and FasL in the homeostatic regulation of immune responses. Immunol Today. 1995;16:569–74. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang X, Brunner T, Carter L, et al. Unequal death in T helper cell (Th)1 and Th2 effectors: Th1, but not Th2, effectors undergo rapid Fas/FasL-mediated apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1837–49. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.10.1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams MA, Ravkov EV, Bevan MJ. Rapid culling of the CD4+ T cell repertoire in the transition from effector to memory. Immunity. 2008;28:533–45. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scriba TJ, Tameris M, Mansoor N, et al. Dose-finding study of the novel tuberculosis vaccine, MVA85A, in healthy BCG-vaccinated infants. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1832–43. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ota MO, Odutola AA, Owiafe PK, et al. Immunogenicity of the tuberculosis vaccine MVA85A is reduced by coadministration with EPI vaccines in a randomized controlled trial in Gambian infants. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:88ra56. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Colditz GA, Berkey CS, Mosteller F, et al. The efficacy of bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccination of newborns and infants in the prevention of tuberculosis: meta-analyses of the published literature. Pediatrics. 1995;96:29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fine PE. Variation in protection by BCG: implications of and for heterologous immunity. Lancet. 1995;346:1339–45. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harari A, Vallelian F, Meylan PR, Pantaleo G. Functional heterogeneity of memory CD4 T cell responses in different conditions of antigen exposure and persistence. J Immunol. 2005;174:1037–45. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harari A, Vallelian F, Pantaleo G. Phenotypic heterogeneity of antigen-specific CD4 T cells under different conditions of antigen persistence and antigen load. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:3525–33. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Appay V, Dunbar PR, Callan M, et al. Memory CD8+ T cells vary in differentiation phenotype in different persistent virus infections. Nat Med. 2002;8:379–85. doi: 10.1038/nm0402-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iezzi G, Karjalainen K, Lanzavecchia A. The duration of antigenic stimulation determines the fate of naive and effector T cells. Immunity. 1998;8:89–95. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80461-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Golden-Mason L, Burton JR, Jr, Castelblanco N, et al. Loss of IL-7 receptor alpha-chain (CD127) expression in acute HCV infection associated with viral persistence. Hepatology. 2006;44:1098–109. doi: 10.1002/hep.21365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wherry EJ, Ha SJ, Kaech SM, et al. Molecular signature of CD8+ T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Immunity. 2007;27:670–84. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kagina BM, Abel B, Scriba TJ, et al. Specific T cell frequency and cytokine expression profile do not correlate with protection against tuberculosis after bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccination of newborns. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:1073–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201003-0334OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dudani R, Chapdelaine Y, Faassen Hv H, et al. Multiple mechanisms compensate to enhance tumor-protective CD8(+) T cell response in the long-term despite poor CD8(+) T cell priming initially: comparison between an acute versus a chronic intracellular bacterium expressing a model antigen. J Immunol. 2002;168:5737–45. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.