Abstract

A cross-sectional study of Blastocystis infection was conducted to evaluate the prevalence, risk factors, and subtypes of Blastocystis at the Home for Girls, Bangkok, Thailand in November 2008. Of 370 stool samples, 118 (31.9%) were infected with Blastocystis. Genotypic characterization of Blastocystis was performed by polymerase chain reaction and sequence analysis of the partial small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) gene. Subtype 1 was the most predominant (94.8%), followed by subtype 6 (3.5%) and subtype 2 (1.7%). Sequence analyses revealed nucleotide polymorphisms for Blastocystis subtype 1, which were described as subtype 1/variant 1, subtype 1/variant 2. Blastocystis subtype 1/variant 1 was the most predominant infection occurring in almost every house. The results showed that subtype analysis of Blastocystis was useful for molecular epidemiological study.

Introduction

Blastocystis is a common intestinal parasite found in humans and a wide range of animals.1–6 Individuals infected with Blastocystis were mostly asymptomatic, whereas some patients presented with acute or chronic gastrointestinal illness.7–9 Blastocystis infection has been reported from both developed and developing countries.10 In Thailand, epidemiological studies of Blastocystis infection showed the prevalence of 10–40% in different populations.3,11–15 Using molecular methods, extensive genetic diversity was detected among Blastocystis populations.16–18 Recently, a consensus terminology for subtypes of Blastocystis was developed on the basis of small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) gene analysis for which at least 13 subtypes have been characterized from humans and animals.5,6,19 These subtypes are not host-specific and cross-infectivity may occur among humans and animals. Subtype characterization of Blastocystis is important for epidemiological studies that could help identify sources and potential routes of transmission of Blastocystis in each particular area. Subtype 3 is the most common subtype found in humans, however in Thailand subtype 1 appears to predominate followed by subtypes 2, 3, 5, 6, and 7.3,10,14,20

Our recent study showed that Blastocystis was common in an orphanage for young children in Bangkok and possibly transmitted from person to person.15 The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence and risk factors of Blastocystis infection in the Home for Girls, an orphanage for girls with different age groups and living environments and to characterize subtypes of Blastocystis isolated from these girls to understand the epidemiology of Blastocystis infection in this population.

Materials and Methods

Study population.

A cross-sectional study of Blastocystis infection was conducted at the Home for Girls, Bangkok, in November 2008. The Home for Girls was established to provide welfare for abused and neglected girls. The study population consisted of 463 female participants between 5 and 25 years of age. The accommodation was arranged in cottage-typed housing and had a capacity for 13 to 27 girls with different age groups in one house. There were 19 houses located next to each other having its own yard, rooms, kitchen, and cooking facilities. Drinking water was provided in each house using a filtered device. The institute did not allow these girls to have pets. However, dogs and cats were often seen around the area. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committee of the Royal Thai Army Medical Department. Informed consents were obtained from the participants and/or the guardian before enrollment.

Collection and processing of fecal samples.

A stool specimen of each enrolled subject was collected and examined for Blastocystis by in vitro cultivation using Jones' medium supplemented with 10% horse serum.21 Samples were incubated at 37°C for 2–3 days and examined for Blastocystis by light microscopy. Stool specimens of six domestic dogs were also processed by the same method. All positive cultured samples were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline and extracted for DNA using QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), following the manufacturer's instructions. The extracted DNA of each sample was kept frozen at −20°C until used.

Collection and processing of drinking water samples.

Six liters of drinking water samples were collected from every house for the detection of Blastocystis using in vitro cultivation and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methods. These water samples were filtered using 0.22-μm filters. Each filter paper was then cut into two pieces for cultivation in Jones' medium and for genomic DNA extraction. The DNA extraction was performed using UltraClean Water DNA Isolation Kit (MO BIO Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The extracted DNA of water samples was kept frozen at −20°C until used.

PCR of SSU rRNA region.

Extracted DNA of Blastocystis from stool specimens and drinking water was amplified using the nested PCR technique. Primary and secondary PCR were carried out using primers and conditions described by Clark and others17 and Böhm-Gloning and others,16 respectively. The 1,100 bp of secondary PCR product was visualized by gel electrophoresis using 2% agarose gel and documented on high density printing paper using Uvisave gel documentation system I (Uvitech, Cambridge, UK).

DNA sequencing and subtype analysis.

To subtype and characterize genetic diversity of each subtype, all PCR products from 58 samples were directly sequenced and chromatograms were validated using BioEdit version 7.0.1 (Isis Pharmaceuticals Inc., Carlsbad, CA). Subsequently, 1,005 bp of nucleotide sequences of the SSU rRNA gene of Blastocystis obtained in this study were multiple aligned with a set of 44 other Blastocystis isolates retrieved from the GenBank database including representatives of all known Blastocystis subtypes using ClustalX version 2.0.12.22 Phylogenetic analysis was carried out using MrBAYES version 3.1.2.23 Bayesian analyses of the SSU rRNA data set were performed using the GTR (general time reversible) + Γ (gamma distribution of rates with four rate categories) + Ι (proportion of invariant sites) model of sequence evolution. In Bayesian analyses, starting trees were random, four simultaneous Markov chains were run for 500,000 generations, burn-in values were set at 30,000 generations, and trees were sampled every 100 generations. Bayesian posterior probabilities were calculated using a Markov chain Monte Carlo sampling approach implemented in MrBAYES version 3.1.223; all sequences obtained from this study were submitted to GenBank under the accession no. JQ665844–JQ665872.

Questionnaire.

To determine the risk factors and outcomes of Blastocystis infections, standardized questionnaires concerning demographic data, risk behaviors, and clinical outcomes were included. Diarrhea was defined as a change in the normal pattern of bowel movements and at least three loose stools during a 24-h period, and dysentery was defined as at least one passage of mucous bloody stool in 1 day. The enrolled subjects in each house were asked to collect stool samples and complete standardized questionnaires. Older girls of each house were asked to collect stool samples and complete the questionnaires for some younger girls. The weight and the height of each individual were recorded. To determine their nutritional status, INMU Thai-growth, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand, 1995 was used as standard reference.24

Statistical analysis.

The association between potential risk factors and Blastocystis infection was assessed by the χ2 or Fisher's exact test with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Univariate analysis was performed using STATA version 9.2. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs and P values were calculated to compare outcomes among study groups. Logistic regression was performed for multivariate analysis to assess the independent association of risk factors and Blastocystis infection.

Results

Prevalence of Blastocystis infection.

In all, 370 participants from the Home for Girls were enrolled in this study with a response rate of 79.9%. The characteristics of infected participants are shown in Table 1; the median age of the girls was 11.8 (5.5 to 24.9) years. Overall prevalence of Blastocystis infection in this community was 31.9% (118 of 370). Of 19 households, Blastocystis infection was found in every household with a prevalence ranging from 7.7% to 47.8%. Houses 9, 14, 17, and 19 had a higher Blastocystis prevalence compared with the other 15 houses. However, no statistical differences were found for Blastocystis infection among these households (P > 0.05) (Table 1). All Blastocystis-infected girls showed no gastrointestinal symptoms.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the enrolled subjects and the prevalence of Blastocystis infection

| Characteristic | No. enrolled subjects | No. (%) infected subjects | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age: median (range) years | |||

| 11.8 (5.5–24.9) | |||

| House no. | |||

| 1 | 17 | 4 (23.5) | |

| 2 | 10 | 2 (20.0) | |

| 3 | 17 | 6 (35.3) | |

| 4 | 26 | 6 (23.1) | |

| 5 | 24 | 7 (29.2) | |

| 6 | 20 | 6 (30.0) | |

| 7 | 27 | 9 (33.3) | |

| 8 | 19 | 5 (26.3) | |

| 9 | 23 | 11 (47.8) | |

| 10 | 22 | 8 (36.4) | |

| 11 | 26 | 9 (34.6) | |

| 12 | 13 | 1 (7.7) | |

| 13 | 17 | 7 (41.2) | |

| 14 | 17 | 8 (47.1) | |

| 15 | 20 | 6 (30.0) | |

| 16 | 19 | 2 (10.5) | |

| 17 | 22 | 10 (45.5) | |

| 18 | 18 | 5 (27.8) | |

| 19 | 13 | 6 (46.2) | 0.402 |

| Nutrition status | |||

| Normal nutrition status | 282 | 95 (33.7) | |

| Under nutrition status | 33 | 10 (30.3) | |

| Over nutrition status | 36 | 10 (27.8) | 0.776 |

| Education level | |||

| Kindergarten | 3 | 2 (66.7) | |

| Primary school | 243 | 71 (29.2) | |

| Secondary school | 60 | 21 (35.0) | |

| Others | 63 | 23 (36.5) | 0.339 |

| Total | 370 | 118 (31.9) | |

Using both in vitro cultivation and PCR methods, stool specimens collected from six domestic dogs showed negative results for Blastocystis. In addition, samples of drinking water collected from every household also gave negative results.

Risk factors of Blastocystis infection.

Univariate analysis of the risk association for Blastocystis infection in this community showed that those with unwashed hands before cooking (OR = 1.8, 95% CI = 1.1–2.8), having a history of contacting pets (OR = 1.9, 95% CI = 1.0–3.5), and with unwashed hands after contacting pets (OR = 2.0, 95% CI = 1.2–3.1) had a higher risk of acquiring Blastocystis infection (Table 2). Multivariate analysis showed that the participants who had not washed their hands after contacting pets were 1.8 times at higher risk of acquiring Blastocystis infection (95% CI = 1.0–3.0) than those who did after adjusting for age, nutrition status, washing hands before cooking, and contacting pets (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors for Blastocystis infection

| Characteristic | No. enrolled subjects | No. (%) infected subjects | Crude OR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age: median (range) years | |||||||

| 11.8 (5.5–24.9) | 370 | 118 | (31.9) | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) | 0.581 | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) | 0.479 |

| Nutrition status | |||||||

| Normal nutrition status | 282 | 95 | (33.7) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Under nutrition status | 33 | 10 | (30.3) | 0.9 (0.4–1.9) | 0.697 | 0.8 (0.3–1.9) | 0.603 |

| Over nutrition status | 36 | 10 | (27.8) | 0.8 (0.4–1.6) | 0.497 | 0.9 (0.4–2.0) | 0.899 |

| Wash hands before cooking | |||||||

| Every time | 204 | 54 | (26.5) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Occasional | 154 | 60 | (39.0) | 1.8 (1.1–2.8) | 0.012* | 1.3 (0.8–2.2) | 0.293 |

| Contact pets | |||||||

| No | 73 | 16 | (21.9) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 281 | 97 | (34.5) | 1.9 (1.0–3.5) | 0.040* | 1.4 (0.7–2.9) | 0.304 |

| Wash hands after contact pets | |||||||

| Yes | 228 | 61 | (26.8) | 1 | 1 | ||

| No | 122 | 51 | (41.8) | 2.0 (1.2–3.1) | 0.004* | 1.8 (1.0–3.0) | 0.044* |

Data were adjusted for age, nutrition status, wash hands before cooking, and contact with pets.

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Sequence analysis of partial SSU rRNA of Blastocystis.

Of 118 cultured positive stool samples, PCR amplification was successful for 58 samples (49.2%). Of which, one (1.7%) and 2 (3.5%) positive samples were identified as subtype 2 and subtype 6, respectively. The nucleotide sequences of subtypes 2 and 6 obtained from this study were a 99% match with those previously reported in GenBank (accession no. AB070997 and AB91237, respectively).

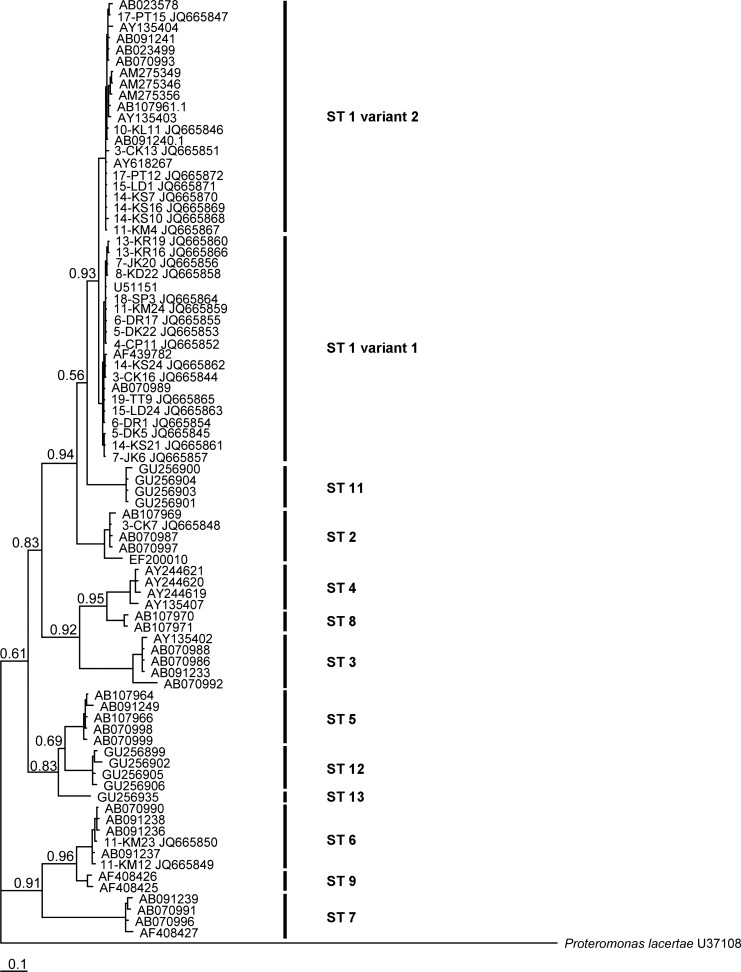

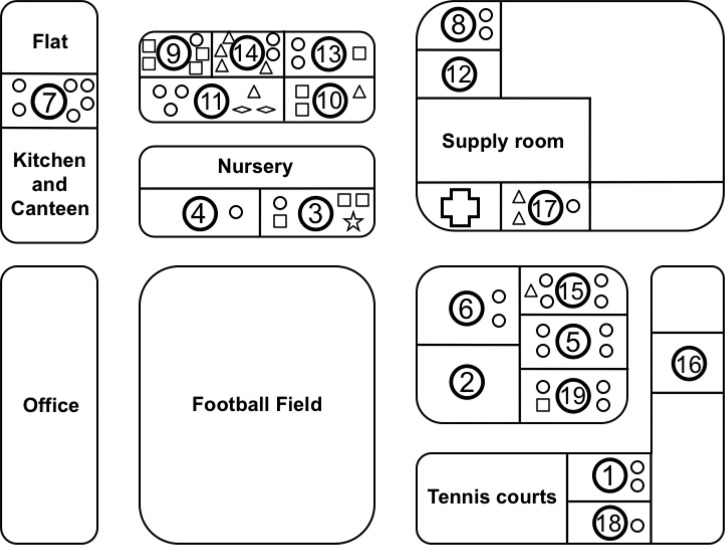

Of the remaining samples, 55 samples (94.8%) were subtype 1, which showed 97–99% nucleotide identity to the previously reported sequence (accession no. AF439782). Interestingly, the nucleotide region between positions 616 and 655 of the subtype 1 showed the areas of high diversity (60%) and could be segregated into two different patterns (Figure 1 ). On the basis of these differences, subtype 1 was further classified as subtype 1/variant 1 and subtype 1/variant 2. The prevalence of these two variants were 63.6% (35 samples) and 16.4% (9 samples), respectively, whereas another 20% (11 samples) were co-infections. The existence of these variants was strongly supported by the posterior probability at 0.93 calculated by Bayesian tree analysis using nucleotide sequences obtained from this study and reference sequences of all 13 subtypes found in Blastocystis (Figure 2 ).

Figure 1.

Variation patterns of the partial small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) gene of Blastocystis subtype 1 at positions between 616 and 655. A dot indicates a nucleotide identical to that of the top sequence.

Figure 2.

The Bayesian phylogenetic tree of Blastocystis isolates inferred from partial small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) gene sequences. The representative sequences of Blastocystis subtype 1/variant 1, subtype 1/variant 2, subtypes 2 and 6 were used for phylogenetic analysis.

Distribution of Blastocystis subtypes in households.

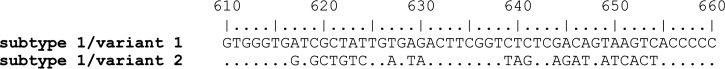

Distribution of Blastocystis subtypes among girls living in each household is shown in Figure 3 ; in this institute, Blastocystis subtype 1/variant 1 was predominant. Of 16 households, the subtype 1/variant 1 was identified in 15 households, whereas subtype 1/variant 2 was found in 5 households (Houses 10, 11, 14, 15, and 17). Co-infection of subtype 1/variant 1 and subtype 1/variant 2 was also found in five households (Houses 3, 9, 10, 13, and 19). Subtype 2 and subtype 6 were found only in Houses 3 and 11, respectively. Unfortunately, none of the positive Blastocystis samples in three households, i.e., Houses 2, 16, and 12 were determined for the subtype because of unsuccessful PCR amplification.

Figure 3.

Schematic map of the House at Home for Girls and widespread distribution of Blastocystis subtype in each household. ○: subtype 1/variant 1, △: subtype 1/variant 2, □: subtype 1/variant 1 mixed with variant 2, ⋆: subtype 2, ⋄: subtype 6

Discussion

This study showed that the prevalence of Blastocystis infection in the Home for Girls, Bangkok, Thailand was apparently high when compared with the previous community studies in Thailand (31.9% versus 2.2–18.9%).3,11–15 Blastocystis can be classified into at least 13 subtypes based on the information of the SSU rRNA gene.5,6,19 Among these, subtype 3 is predominant, and usually found in both symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals, except those in Thailand and Brazil.12,14,25 Studies from different communities in these two countries showed contrasting results, i.e., that subtype 1 is the most predominant.3,14,20 The prevalence of subtype 1 is 1.1 to 26.5 times higher than those of other countries.10 From our study, the results were consistent with previous findings that subtype 1 was the most common, whereas subtype 3 was not detected. In addition, subtypes 2 and 6 were also identified.

Previous studies have shown the evidence of person-to-person, waterborne, and zoonotic transmission of Blastocystis infection11–14,20,26,27; the route of transmission of this organism could be different depending on the study population. In this study, the data concerning all routes of transmission were collected to elucidate the source of infection. The Home for Girls is a close community where most girls live and study in a boarding elementary school located in the area, and thus, the likelihood of getting the infection within the household and also in the community should be very high. Moreover, one-third of the grown-up girls were allowed to study at secondary schools located outside the area where infection of Blastocystis could have occurred. In addition, ∼3–5 new girls were transferred to stay at the Home for Girls every month and had no parasite screening before moving in. Thus, getting Blastocystis infection from outside the community could not be excluded and these could possibly explain the small number of infections caused by subtypes 2 and 6 in some girls.

Person-to-person transmission might be a possible route of Blastocystis infection in this community setting because these girls had been sharing all facilities within the same households for months to years. The likelihood of getting Blastocystis infection from the others should not be uncommon. Additionally, transferring some girls to other houses during their stay could spread Blastocystis among houses. This assumption could be supported by the distinctly higher prevalence of one subtype over the others. An apparently higher prevalence of the mixed infection of subtypes in this community also supported and strengthened the possibility of person-to-person transmission when compared with the prevalence of Blastocystis infection in other studies (20% versus 1.1–14.3%).28–30

Zoonotic transmission of Blastocystis in this population could be possible. Multivariate analysis showed that the girls who did not wash their hands after contacting pets had a high risk of getting Blastocystis infection. Previous studies identified subtype 1 in a wide range of animals and phylogenetic analysis also showed the zoonotic potential of this subtype.2–4 However, conclusive evidence of zoonotic transmission could not be revealed in this study because stool samples collected from six dogs showed negative results for Blastocystis infection. All stray dogs had been displaced from the community a few weeks before stool samples were collected, thus leaving only six dogs to be included in the study. Additionally, collected stool samples from a number of cats, frequently seen roaming around the area where the girls frequently played, were not successfully done.

Waterborne transmission of Blastocystis infection has been indicated in a few studies11–14; a survey of parasitic infections in primary school children of a rural community, central Thailand, showed a high prevalence of Blastocystis subtype 1. Blastocystis subtype 1 was also found in the drinking water.14 In this study, samples of drinking water collected from all households including those provided from the canteen, the main kitchen, and the nursing care room showed negative results of Blastocystis by both in vitro cultivation and PCR. Therefore, evidence did not provide significant support for waterborne transmission in this community setting.

Blastocystis is one of the organisms that have been studied to increase discriminatory power at the subspecies level. In this regard, the technique to assemble the data from different genes to analyze as a set has been proved to be very promising.31 However, the multilocus analysis recently demonstrated by Stensvold and others32 showed insignificant improvement on discriminatory power when compared with the results obtained from a single locus, SSU rRNA. Nevertheless, the results of their study implied that SSU rRNA is a very informative gene and is the target gene of choice for subtyping Blastocystis. In fact, the sequence pattern of subtype 1/variant 2 has already been discovered. Nonetheless, this subtype appears as a minority subtype, that to date, only 14 records from 9 reports have been deposited in the GenBank sequence database compared with hundreds of records of subtype 1/variant 1.2,3,33–38 As most of the subtype 1/variant 2 isolates were reported in non-community-based studies, the identification of up to 20 isolates in this study emphasized the importance and usefulness of subtype identification in terms of epidemiological studies.

Uneven distribution of each subtype of Blastocystis could be explained by having incomplete molecular data because only half of the stool samples were successfully subtyped. Further investigation using a cohort study could provide in-depth information of molecular epidemiology and reveal the potential transmission routes of Blastocystis in this community.

In conclusion, polymorphisms of Blastocystis subtype 1 were detected in this setting, which could be used as a tool for epidemiological studies. Blastocystis subtype 1/variant 1 was predominant among households indicating the infection occurred within the community. Infection with similar subtypes and variants of Blastocystis might indicate person-to-person transmission. Risk analysis also provided evidence of zoonotic transmission of Blastocystis infection in this community. This information is necessary for setting prevention and control programs for this community.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully thank the director, childcare workers, and the enrolled girls of the Home for Girls for their support of this study.

Footnotes

Financial support; This work was supported by the Phramongkutklao Research Fund, Phramongkutklao College of Medicine, Thailand, Faculty of Science, Burapha University, Thailand, and The Royal Golden Jubilee Ph.D. Program (Grant No. PHD/0236/2548).

Authors' addresses: Umaporn Thathaisong, Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Science, Burapha University, Chonburi, Thailand, E-mail: kungking65@hotmail.com. Suradej Siripattanapipong, Mathirut Mungthin, Tawee Naaglor, and Saovanee Leelayoova, Department of Parasitology, Phramongkutklao College of Medicine, Bangkok, Thailand, E-mails: suradejs@rocketmail.com, mathirut@pmk.ac.th, tawee_narkloar@hotmail.com, and s_leelayoova@scientist.com. Duangnate Pipatsatitpong, Department of Medical Technology, Faculty of Allied Health Sciences, Thammasat University, Khlong Luang, Pathum Thani, Thailand, E-mail: duangnate_pipat@hotmail.com. Peerapan Tan-ariya, Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Science, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand, E-mail: scptn@mahidol.ac.th.

References

- 1.Abe N, Wu Z, Yoshikawa H. Zoonotic genotypes of Blastocystis hominis detected in cattle and pigs by PCR with diagnostic primers and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the small subunit ribosomal RNA gene. Parasitol Res. 2003;90:124–128. doi: 10.1007/s00436-002-0821-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noel C, Peyronnet C, Gerbod D, Edgcomb VP, Delgado-Viscogliosi P, Sogin ML, Capron M, Viscogliosi E, Zenner L. Phylogenetic analysis of Blastocystis isolates from different hosts based on the comparison of small-subunit rRNA gene sequences. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2003;126:119–123. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(02)00246-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thathaisong U, Worapong J, Mungthin M, Tan-Ariya P, Viputtigul K, Sudatis A, Noonai A, Leelayoova S. Blastocystis isolates from a pig and a horse are closely related to Blastocystis hominis. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:967–975. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.3.967-975.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noel C, Dufernez F, Gerbod D, Edgcomb VP, Delgado-Viscogliosi P, Ho LC, Singh M, Wintjens R, Sogin ML, Capron M, Pierce R, Zenner L, Viscogliosi E. Molecular phylogenies of Blastocystis isolates from different hosts: implications for genetic diversity, identification of species, and zoonosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:348–355. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.1.348-355.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stensvold CR, Alfellani MA, Norskov-Lauritsen S, Prip K, Victory EL, Maddox C, Nielsen HV, Clark CG. Subtype distribution of Blastocystis isolates from synanthropic and zoo animals and identification of a new subtype. Int J Parasitol. 2009;39:473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parkar U, Traub RJ, Vitali S, Elliot A, Levecke B, Robertson I, Geurden T, Steele J, Drake B, Thompson RC. Molecular characterization of Blastocystis isolates from zoo animals and their animal-keepers. Vet Parasitol. 2010;169:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boorom KF, Smith H, Nimri L, Viscogliosi E, Spanakos G, Parkar U, Li LH, Zhou XN, Ok UZ, Leelayoova S, Jones MS. Oh my aching gut: irritable bowel syndrome, Blastocystis, and asymptomatic infection. Parasit Vectors. 2008;1:40. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-1-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coyle CM, Varughese J, Weiss LM, Tanowitz HB. Blastocystis: to treat or not to treat. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:105–110. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poirier P, Wawrzyniak I, Vivares CP, Delbac F, El Alaoui H. New insights into Blastocystis spp.: a potential link with irritable bowel syndrome. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002545. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan KS. New insights on classification, identification, and clinical relevance of Blastocystis spp. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:639–665. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00022-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taamasri P, Mungthin M, Rangsin R, Tongupprakarn B, Areekul W, Leelayoova S. Transmission of intestinal blastocystosis related to the quality of drinking water. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2000;31:112–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taamasri P, Leelayoova S, Rangsin R, Naaglor T, Ketupanya A, Mungthin M. Prevalence of Blastocystis hominis carriage in Thai army personnel based in Chonburi, Thailand. Mil Med. 2002;167:643–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leelayoova S, Rangsin R, Taamasri P, Naaglor T, Thathaisong U, Mungthin M. Evidence of waterborne transmission of Blastocystis hominis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;70:658–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leelayoova S, Siripattanapipong S, Thathaisong U, Naaglor T, Taamasri P, Piyaraj P, Mungthin M. Drinking water: a possible source of Blastocystis spp. subtype 1 infection in schoolchildren of a rural community in central Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:401–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pipatsatitpong D, Rangsin R, Leelayoova S, Naaglor T, Mungthin M. Incidence and risk factors of Blastocystis infection in an orphanage in Bangkok, Thailand. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:37. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bohm-Gloning B, Knobloch J, Walderich B. Five subgroups of Blastocystis hominis from symptomatic and asymptomatic patients revealed by restriction site analysis of PCR-amplified 16S-like rDNA. Trop Med Int Health. 1997;2:771–778. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1997.d01-383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark CG. Extensive genetic diversity in Blastocystis hominis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;87:79–83. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshikawa H, Wu Z, Kimata I, Iseki M, Ali IK, Hossain MB, Zaman V, Haque R, Takahashi Y. Polymerase chain reaction-based genotype classification among human Blastocystis hominis populations isolated from different countries. Parasitol Res. 2004;92:22–29. doi: 10.1007/s00436-003-0995-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stensvold CR, Suresh GK, Tan KS, Thompson RC, Traub RJ, Viscogliosi E, Yoshikawa H, Clark CG. Terminology for Blastocystis subtypes–a consensus. Trends Parasitol. 2007;23:93–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parkar U, Traub RJ, Kumar S, Mungthin M, Vitali S, Leelayoova S, Morris K, Thompson RC. Direct characterization of Blastocystis from feces by PCR and evidence of zoonotic potential. Parasitology. 2007;134:359–367. doi: 10.1017/S0031182006001582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leelayoova S, Taamasri P, Rangsin R, Naaglor T, Thathaisong U, Mungthin M. In-vitro cultivation: a sensitive method for detecting Blastocystis hominis. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2002;96:803–807. doi: 10.1179/000349802125002275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.INMU Thai-growth Institute of Nutrition, Mahidol University. 2009. http://www.inmu.mahidol.ac.th/thaigrowth/ Available at. Assessed September 1, 2009.

- 25.Malheiros AF, Stensvold CR, Clark CG, Braga GB, Shaw JJ. Short report: molecular characterization of Blastocystis obtained from members of the indigenous Tapirape ethnic group from the Brazilian Amazon region, Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85:1050–1053. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.11-0481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshikawa H, Abe N, Iwasawa M, Kitano S, Nagano I, Wu Z, Takahashi Y. Genomic analysis of Blastocystis hominis strains isolated from two long-term health care facilities. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1324–1330. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.4.1324-1330.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li LH, Zhou XN, Du ZW, Wang XZ, Wang LB, Jiang JY, Yoshikawa H, Steinmann P, Utzinger J, Wu Z, Chen JX, Chen SH, Zhang L. Molecular epidemiology of human Blastocystis in a village in Yunnan province, China. Parasitol Int. 2007;56:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong KH, Ng GC, Lin RT, Yoshikawa H, Taylor MB, Tan KS. Predominance of subtype 3 among Blastocystis isolates from a major hospital in Singapore. Parasitol Res. 2008;102:663–670. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0808-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yan Y, Su S, Lai R, Liao H, Ye J, Li X, Luo X, Chen G. Genetic variability of Blastocystis hominis isolates in China. Parasitol Res. 2006;99:597–601. doi: 10.1007/s00436-006-0186-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yan Y, Su S, Ye J, Lai X, Lai R, Liao H, Chen G, Zhang R, Hou Z, Luo X. Blastocystis sp. subtype 5: a possibly zoonotic genotype. Parasitol Res. 2007;101:1527–1532. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0672-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maiden MC. Multilocus sequence typing of bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2006;60:561–588. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stensvold CR, Alfellani M, Clark CG. Levels of genetic diversity vary dramatically between Blastocystis subtypes. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santin M, Gomez-Munoz MT, Solano-Aguilar G, Fayer R. Development of a new PCR protocol to detect and subtype Blastocystis spp. from humans and animals. Parasitol Res. 2011;109:205–212. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-2244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arisue N, Hashimoto T, Yoshikawa H. Sequence heterogeneity of the small subunit ribosomal RNA genes among Blastocystis isolates. Parasitology. 2003;126:1–9. doi: 10.1017/s0031182002002640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arisue N, Hashimoto T, Yoshikawa H, Nakamura Y, Nakamura G, Nakamura F, Yano TA, Hasegawa M. Phylogenetic position of Blastocystis hominis and of stramenopiles inferred from multiple molecular sequence data. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2002;49:42–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2002.tb00339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stensvold CR, Arendrup MC, Jespersgaard C, Molbak K, Nielsen HV. Detecting Blastocystis using parasitologic and DNA-based methods: a comparative study. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;59:303–307. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stensvold CR, Traub RJ, von Samson-Himmelstjerna G, Jespersgaard C, Nielsen HV, Thompson RC. Blastocystis: subtyping isolates using pyrosequencing technology. Exp Parasitol. 2007;116:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abe N. Molecular and phylogenetic analysis of Blastocystis isolates from various hosts. Vet Parasitol. 2004;120:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]