Abstract

Immigrants returning home to visit friends and relatives (VFR travelers) are at higher risk of travel-associated illness than other international travelers. We evaluated 3,707 VFR and 17,507 non-VFR travelers seen for pre-travel consultation in Global TravEpiNet during 2009–2011; all were traveling to resource-poor destinations. VFR travelers more commonly visited urban destinations than non-VFR travelers (42% versus 30%, P < 0.0001); 54% of VFR travelers were female, and 18% of VFR travelers were under 6 years old. VFR travelers sought health advice closer to their departure than non-VFR travelers (median days before departure was 17 versus 26, P < 0.0001). In multivariable analysis, being a VFR traveler was an independent predictor of declining a recommended vaccine. Missed opportunities for vaccination could be addressed by improving the timing of pre-travel health care and increasing the acceptance of vaccines. Making pre-travel health care available in primary care settings may be one step to this goal.

Introduction

Approximately 12% of the United States population are foreign-born, and another 11% are native-born with at least one foreign-born parent.1 Members of this immigrant population who are traveling home to visit friends or relatives in lower-income countries (VFR travelers) are at higher risk of travel-related infectious diseases than the general population of international travelers.2,3 In US surveillance data from 2010, 71% of imported malaria cases in travelers with an identified purpose of travel were VFR travelers.4 These VFR travelers with malaria were significantly less likely to have taken chemoprophylaxis than individuals traveling for other purposes. As with malaria, the majority of travel-associated typhoid fever cases in the United States in 1999–2006 also occurred in VFR travelers.5 Enteric (typhoid and paratyphoid) fever was the most common vaccine-preventable disease among ill returned travelers seen over a decade by the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network.6 VFR travel, particularly to South Central Asia, was an independent risk factor for enteric fever in this population. Other infectious diseases, including hepatitis A, measles, tuberculosis, and others, are also more common in VFR travelers.6–9

There are multiple potential reasons for the increased risk of travel-related illness in VFR travelers, including lower socioeconomic status, language barriers, behavioral differences while traveling, and presumption of immunity to infections found at the travel destinations. Disease prevention strategies for VFR travelers are a public health priority and are aimed at decreasing the burden of illness in this population as well as at curbing the global spread of infectious diseases.10,11 Primary care practitioners are the most common source of pre-travel health advice for VFR travelers,12 although airport surveys of departing travelers have repeatedly shown that many VFR travelers do not seek pre-travel health advice.12–14

Here, we evaluate a large cohort of VFR travelers who obtained pre-travel health advice within Global TravEpiNet, a consortium of US practices that provide care to international travelers. Our goal was to better understand the demographics, itineraries, and pre-travel health care of VFR travelers who sought pre-travel health advice and identify areas in which the care of this population could be improved.

Methods

Global TravEpiNet clinics.

Global TravEpiNet is a consortium of US practices that is sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as previously described.15 Global TravEpiNet sites are distributed across the United States and include academic practices, health care consortia, health maintenance organizations, pharmacy-based clinics, private practices, and public health clinics. An institutional review board at each participating site reviewed and approved the study.

Study population.

Clinicians collected data on all individuals seen for pre-travel consultation at participating sites from January of 2009 to December of 2011 using a secure internet tool. For each unique clinic visit, travelers provided details about their medical history, itinerary, and travel purpose. Clinicians verified the information provided by travelers and entered additional data on immunization history, health advice provided, vaccines administered, and medications prescribed during the pre-travel encounter. If a traveler had an indication for a vaccine according to CDC guidelines that were current at the time of the clinic visit, but the vaccine was not administered, the clinician was required to provide a reason for not administering the vaccine; available options included pre-existing immunity, vaccine not indicated, referred to primary care provider for vaccination, patient declined, medical contraindication, insufficient time, or vaccine not available.

Data analysis.

Geographic destinations were classified into regions according to the grouping of member states of the World Health Organization (WHO) (http://www.who.int/about/regions/en/index.html) and income categories (low income, lower middle income, upper middle income, or high income) according to the 2009 World Bank World Development Report (http://econ.worldbank.org).16 For purposes of analysis, we considered travel to low- or lower middle-income (LLMI) countries to be highest risk, and travelers to these two destination categories were considered together. Countries with risk of malaria or yellow fever transmission were defined in accordance with the CDC categorization for the time period of the study.2,17 We accounted for the revised yellow fever vaccine recommendations for those individuals traveling after April 1, 2011 in our definition of destinations requiring yellow fever vaccine.2

Travelers selected one or more of the following purposes for their trip: leisure, business, returning to region of origin of self or family to visit friends and relatives, adoption, providing medical care, receiving medical care, research/education, non-medical service work, missionary work, military service, adventuring, attending large gathering or event, or other activities. Travelers also provided information regarding the planned accommodations for their trip. In accordance with the CDC definition of the term,2 we defined a VFR traveler as an individual who was traveling to an LLMI country and who (1) selected “traveling to region of origin of self or family to visit friends or relatives” as their purpose of travel or (2) stated that they would be pursuing a home stay with relatives on their trip. For the present analysis, we compare VFR travelers with travelers to LLMI countries who were traveling for other purposes.

Data analyses were performed using Stata 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) and Excel 2003 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). We used Kruskal–Wallis equality of proportions test, Somers' D test, and separate random intercept logistic regressions with clinical site as the random effect to evaluate measures of association and statistical significance in the data. We also performed multivariable logistic regression analyses to examine the effect of individual variables on the likelihood of declining a vaccine using random effects estimation to account for variances by clinical site. We analyzed the following variables in the logistic regression: traveler's age (≥ 18 versus < 18 years), duration of travel (> 28 versus ≤ 28 days), sex, region of birth, number of medical concerns (≥ 2 versus < 2), region of destination, reason for visiting the clinic, and purpose of travel. For analyzing vaccine declinations, we compared travelers who received the vaccine in association with the clinic visit with those travelers who declined to be vaccinated.

Results

We included 3,707 VFR and 17,507 non-VFR travelers in our analysis; all were traveling to an LLMI country as defined by the World Bank. Females comprised a slight majority (54%) of both VFR and non-VFR travelers seen at Global TravEpiNet sites. VFR travelers were significantly younger than non-VFR travelers (median age = 30 years versus 37 years, P < 0.001); 18% of VFR travelers were younger than 6 years of age (Table 1), whereas < 1% of non-VFR travelers were in this age category. VFR travelers pursued trips of longer duration than non-VFR travelers (median duration = 25 days versus 14 days, P < 0.001) and were more likely to visit only urban areas (42% versus 30%, P < 0.0001) (Table 1). Among travelers to Africa, VFR travelers were particularly likely to visit only urban areas (42% of VFR travelers versus 19% of non-VFR travelers to the WHO African region, P < 0.01). VFR travelers also sought pre-travel health care closer to their departure date than non-VFR travelers (median = 17 days versus 26 days prior to departure, P < 0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and travel-related characteristics of VFR travelers compared with non-VFR travelers at Global TravEpiNet from January of 2009 to December of 2011

| VFR | Non-VFR | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 3,707 | 17,507 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| < 1 | 107 (2.9%) | 7 (< 0.1%) | 0.001 |

| 1–5 | 556 (15.0%) | 83 (0.5%) | 0.001 |

| 6–17 | 550 (14.8%) | 784 (4.5%) | 0.001 |

| 18–49 | 1,820 (49.1%) | 11,080 (63.3%) | 0.001 |

| 50–64 | 498 (13.4%) | 3,822 (21.8%) | 0.001 |

| > 65 | 176 (4.8%) | 1,731 (9.9%) | 0.001 |

| Sex (female) | 2,002 (54.0%) | 9,519 (54.3%) | 0.86 |

| Travel duration | |||

| 1–7 days | 108 (2.9%) | 2,320 (13.3%) | < 0.0001 |

| 8–14 days | 747 (20.1%) | 7,150 (40.8%) | < 0.0001 |

| 15–28 days | 1,165 (31.4%) | 5,011 (28.6%) | < 0.0001 |

| 29–180 days | 1,545 (41.7%) | 2,488 (14.2%) | < 0.0001 |

| > 6 months | 136 (3.7%) | 526 (3.0%) | < 0.0001 |

| Type of destination | |||

| Urban only | 1,542 (41.6%) | 5,116 (29.2%) | < 0.0001 |

| Rural only | 136 (3.7%) | 1,847 (10.6%) | < 0.0001 |

| Both | 2,015 (54.4%) | 10,530 (60.2%) | < 0.0001 |

| Neither | 14 (0.4%) | 14 (0.1%) | < 0.0001 |

| Days to departure (median, IQR) | 17 (8–33) | 26 (12–46) | 0.0001 |

| Top five destination countries | |||

| India (18.1%) | India (17.9%) | ||

| Ghana (8.3%) | China (10.5%) | ||

| Ethiopia (6.0%) | Thailand (9.3%) | ||

| Nigeria (5.9%) | Kenya (8.4%) | ||

| Vietnam (5.6%) | Tanzania (8.3%) | ||

Based on Kruskal–Wallis equality-of-proportions test or Somers' D test as appropriate, adjusted for clustering among clinical sites.

Overall, VFR travelers were more likely than non-VFR travelers to visit countries with regions endemic for malaria or yellow fever. For VFR travelers, the most frequently visited regions were the WHO regions of Africa (46%), Southeast Asia (26%), and the Western Pacific (18%). For non-VFR travelers to LLMI countries, Africa (31%), Southeast Asia (30%), and the Western Pacific (22%) were also the most commonly visited regions. India, Ghana, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Vietnam were the most common destination countries for VFR travelers; aside from India, none of these countries were among the top destinations of non-VFR travelers (Table 1). VFR travel took place most frequently (29% of trips) in the summer months of the northern hemisphere.

VFR travelers had fewer existing medical condition than non-VFR travelers (Table 2). The types of medical conditions also differed between VFR and non-VFR travelers. In particular, VFR travelers were more likely to be pregnant or breastfeeding, and diabetes and immune system disorders were more common in VFR travelers than non-VFR travelers. VFR travelers were less likely to report a neuropsychiatric condition than non-VFR travelers. On average, VFR travelers were taking fewer medications than non-VFR travelers (VFR median = 0, interquartile range [IQR] = 0–1; non-VFR median = 1, IQR = 0–2; P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Medical conditions of VFR travelers compared with non-VFR travelers at Global TravEpiNet from January of 2009 to December of 2011

| Medical condition | VFR N (%) | Non-VFR N (%) | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any medical condition | 2,204 (54.6) | 10,683 (61.0) | < 0.001 |

| Seasonal allergies | 987 (26.6) | 5,630 (32.2) | < 0.001 |

| Heart/cardiovascular | 528 (14.2) | 3,218 (18.4) | < 0.001 |

| Neurological/psychiatric | 222 (6.0) | 1,759 (10.1) | < 0.001 |

| Lung | 326 (8.8) | 1,382 (7.9) | 0.24 |

| Cancer or blood disorder | 182 (4.9) | 1,252 (7.2) | < 0.001 |

| Endocrine disorder | 259 (7.0) | 1334 (7.6) | 0.45 |

| Diabetes | 121 (3.3) | 347 (2.0) | < 0.001 |

| Intestinal system | 173 (4.7) | 1,137 (6.5) | < 0.001 |

| Dermatologic | 218 (5.9) | 1,091 (6.2) | 0.29 |

| Joint | 165 (4.5) | 995 (5.7) | 0.001 |

| Immune system | 132 (3.6) | 392 (2.8) | 0.005 |

| Obstetric/gynecologic | 128 (6.4) | 424 (4.5) | 0.043 |

| Pregnant/breastfeeding | 45 (2.3) | 65 (0.7) | < 0.001 |

| Kidney | 74 (2.0) | 289 (1.7) | 0.17 |

| Liver | 83 (2.2) | 192 (1.1) | < 0.001 |

Based on random intercept logistic regression models with clinical site as the random effect.

We evaluated the malaria chemoprophylaxis agent that was prescribed to travelers going to countries with regions that are endemic for malaria (Table 3). Atovaquone/proguanil was the most commonly prescribed chemoprophylaxis agent for both VFR and non-VFR travelers; however, a much higher proportion of VFR travelers than non-VFR travelers received mefloquine (30.2% versus 3.6%; P < 0.001). VFR travelers more commonly received mefloquine than non-VFR travelers when traveling for 28 days or fewer (17.5% versus 2.5%; P < 0.001) and when traveling for 7 days or fewer (12.7% versus 1.6%; P < 0.001). VFR travelers were less likely than non-VFR travelers to receive prescription antibiotics for travelers' diarrhea (72.6% versus 91.4%; P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Malaria chemoprophylaxis in VFR travelers compared with non-VFR travelers traveling to countries that include regions endemic for malaria

| VFR N (%) | Non-VFR N (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antimalarial (any) | 2,724 (74.7)* | 12,172 (72.0)† | < 0.0001 |

| Atovaquone/proguanil | 1,260 (34.8) | 9,325 (55.6) | |

| Mefloquine | 1,092 (30.2) | 606 (3.6) | |

| Chloroquine | 115 (3.2) | 1,108 (6.6) | |

| Doxycycline | 192 (5.0) | 838 (5.0) | |

| Primaquine | 0 (0) | 5 (< 0.1) |

Sixty-five travelers received more than one prescription or could not be classified.

Two hundred ninety travelers received more than one prescription or could not be classified.

VFR travelers were more likely than non-VFR travelers to have existing immunity to hepatitis A at the time of their pre-travel consultation (47% versus 40%; P < 0.001). Typhoid, hepatitis A, and yellow fever were the three most frequently administered vaccines among VFR travelers and non-VFR travelers alike (administered to 74%, 41%, and 34% of VFR travelers, respectively, and 76%, 55%, and 26% of non-VFR travelers, respectively).

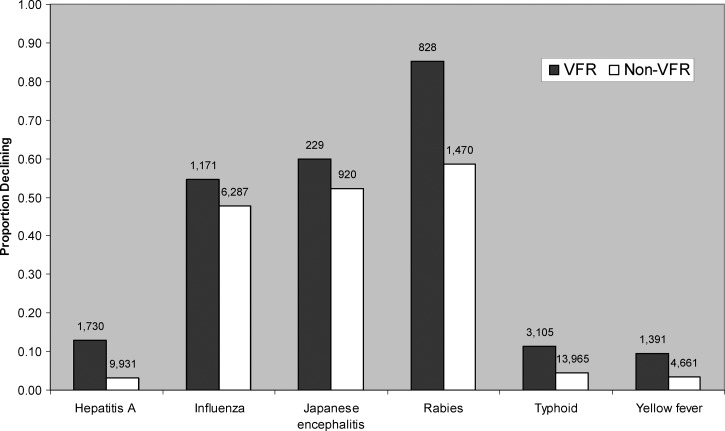

Clinicians were required to provide a reason when vaccines were not administered to travelers to whom they would be otherwise indicated by the current CDC guidelines at the time of the visit. In most (95%) cases, declination by the traveler was cited as the reason for not administering a vaccine. Referral to another provider, medical contraindication, insufficient time to complete the vaccine series before departure, and lack of availability of vaccine were other reasons that were cited less frequently (< 5%). We performed a multivariable analysis to identify predictors of declining any recommended vaccine in the study population. Being a VFR traveler (odds ratio [OR] = 1.30, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.15–1.48), traveling for > 28 days (OR = 1.72, 95% CI = 1.56–1.89), traveling to the WHO African region (OR = 1.21, 95% CI = 1.08–1.35), being an adult (OR = 1.54, 95% CI = 1.32–1.78), and having fewer than two medical concerns (OR = 1.23, 95% CI = 1.13–1.34) were each independently associated with declining a recommended vaccine. In particular, 10% of VFR travelers traveling to yellow fever-endemic countries who were offered the yellow fever vaccine declined it, and 85% of VFR travelers who were offered rabies vaccine declined it (Figure 1). In contrast, 4% of non-VFR travelers visiting yellow fever-endemic countries who were offered the yellow fever vaccine declined it, and 59% of non-VFR travelers who were offered rabies vaccine declined it.

Figure 1.

Proportion of VFR travelers and non-VFR travelers declining selected indicated vaccines at Global TravEpiNet from January of 2009 to December of 2011. The total number of individuals who were administered or declined the vaccine is shown above each column.

Discussion

According to the US Office of Travel and Tourism Industries, 35% of US overseas travelers in 2010 (approximately 10 million travelers) reported visiting friends and relatives as the main purpose of their trip. VFR travelers have repeatedly been identified as a group at higher risk of travel-associated illness,3,7 and prevention strategies targeted at this population are a public health priority.10 Knowledge about existing health conditions, planned itineraries, and pre-travel health care of this large traveling population has been limited to date.

We identified a number of epidemiologically important characteristics of VFR travelers seen at Global TravEpiNet sites. Slightly more female VFR travelers than male VFR travelers were seen for pre-travel health advice. This finding may relate to the fact that women are more likely than men to pursue pre-travel health advice.18 Alternatively, women might, in fact, comprise a majority of VFR travelers. Data from the Office of Travel and Tourism Industries from 2010 indicate that 54% of all US leisure and VFR travelers in 2010 were female19—similar to the proportion identified in Global TravEpiNet. VFR travelers were also significantly younger than non-VFR travelers. In particular, 33% of VFR travelers seen at Global TravEpiNet sites were children, and 18% were children under the age of 6 years. In contrast, children comprised only 8% of all US international travelers in 2010.19 Ease of travel and increased global migration, with a consequent desire to bring children to visit relatives, are likely important reasons why children comprise such a high proportion of VFR travelers. Recent data from the GeoSentinel Network indicate that children are at higher risk of complications from illness acquired while traveling. In an analysis of 10 years of data, 14% of children with travel-related illness required hospitalization compared with 10% of adults.20

In addition to age and sex, there were other important distinctions in itinerary and pre-travel health care between VFR and non-VFR travelers in this study. VFR travelers pursued trips of significantly longer duration, with the majority of itineraries being 1 month or longer. Long-term travel is associated with a unique profile of health risks, including vector-borne illness, contact-transmitted diseases, and psychological problems.21 Importantly, VFR travelers sought pre-travel health advice closer to their departure date than non-VFR travelers—a factor that can limit the ability to complete needed vaccine series. VFR travelers, particularly travelers to the WHO African region, also visited urban destinations more frequently than non-VFR travelers. Patterns of disease risk, including vector-borne disease, zoonotic disease, and trauma, may differ between urban and rural areas, and this finding should be considered during pre-travel counseling.

The itineraries of VFR travelers frequently included areas endemic for malaria, with countries in the WHO African region representing almost one-half of all destinations of VFR travelers. In 2010, 65% of imported malaria cases in the United States with a known region of acquisition were acquired in Africa.4 Lack of malaria chemoprophylaxis or non-adherence to a prescribed prophylactic was common among these imported malaria case patients. By definition, travelers in this cohort all sought pre-travel health care and were offered malaria chemoprophylaxis based on their itinerary. Notably, mefloquine was disproportionately prescribed to VFR travelers compared with non-VFR travelers, regardless of duration of travel. Although less costly, mefloquine has higher rates of gastrointestinal and neuropsychiatric adverse effects compared with other chemoprophylaxis agents,22 particularly among women.23 Identifying optimal strategies for chemoprophylaxis uptake and compliance among VFR travelers, particularly those travelers visiting Africa, is a priority.

Declining recommended vaccines was remarkably common among VFR travelers in this cohort, especially considering that these individuals had sought pre-travel health care. Travelers visiting Africa were particularly likely to decline a recommended vaccine. Declination of recommended vaccines among VFR travelers may relate to cost, concerns about vaccine safety, delayed timing of the pre-travel visit, or lack of perceived risk. Our results indicate that strategies to improve travel vaccine uptake in the VFR population, even among those travelers who seek pre-travel health care, are needed.

An important limitation of our study is that VFR travelers, in general, infrequently seek specialized pre-travel health advice12; travelers seen at Global TravEpiNet sites may, therefore, differ from the overall population of VFR travelers. Nevertheless, even within the population seeking specialized pre-travel care, we were able to identify relevant characteristics of VFR travelers that may affect health outcomes and are appropriate targets for public health interventions. In particular, outreach targeted at women and children, who comprise a substantial proportion of VFR travelers, is needed. Our data suggest that missed opportunities for vaccination in VFR travelers can be addressed by improving the timing of pre-travel health care and increasing the acceptance of recommended vaccines. Making pre-travel health care available in more affordable and accessible primary care settings may be one important step to this goal; our findings, in conjunction with geographic data from the US census, could help target these efforts to appropriate immigrant communities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Members of the Global TravEpiNet Consortium. Members of the Global TravEpiNet Consortium (in alphabetical order) include George M. Abraham, Saint Vincent Hospital (Worcester, MA); Salvador Alvarez, Mayo Clinic (Jacksonville, FL); Vernon Ansdell and Johnnie A. Yates, Travel Medicine Clinic, Kaiser Permanente (Honolulu, HI); Elisha H. Atkins, Chelsea HealthCare Center (Chelsea, MA); John Cahill, Travel and Immunization Center, St. Luke's-Roosevelt (New York, NY); Holly K. Birich and Dagmar Vitek, Salt Lake Valley Health Department (Salt Lake, Utah); Bradley A. Connor, New York Center for Travel and Tropical Medicine, Cornell University (New York, NY); Roberta Dismukes and Phyllis Kozarsky, Emory TravelWell, Emory University (Atlanta, GA); Ronke Dosunmu, JourneyHealth (Maywood, NJ); Jeffrey A. Goad, International Travel Medicine Clinic, University of Southern California (Los Angeles, CA); Stefan Hagmann, Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Bronx Lebanon Hospital Center (Bronx, NY); DeVon Hale, International Travel Clinic, University of Utah (Salt Lake City, UT); Noreen A. Hynes, John Hopkins Travel and Tropical Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, John Hopkins School of Medicine (Baltimore, MD); Frederique Jacquerioz and Susan McLellan, Tulane University (New Orleans, LA); Mark Knouse, Keystone Travel Medicine, Lehigh Valley Health Network (Allentown, PA); Jennifer Lee, Travel and Immunization Center, Northwestern Memorial Hospital (Chicago, IL); Regina C. LaRocque and Edward T. Ryan, Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, MA); Alawode Oladele and Hanna Demeke, DeKalb County Board of Health Travel Services-DeKalb North and Central-T.O. Vinson Centers (Decatur, GA); Roger Pasinski and Amy E. Wheeler, Revere HealthCare Center (Revere, MA); Sowmya R. Rao, University of Massachussetts (Worcester, MA); Jessica Rosen, Infectious Diseases and Travel Medicine, Georgetown University (Washington, DC); Brian S. Schwartz, Travel Medicine and Immunization Clinic, University of California (San Francisco, CA); William Stauffer and Patricia Walker, HealthPartners Travel Medicine Clinics (St. Paul, Minnesota); Lori Tishler, Phyllis Jen Center for Primary Care, Brigham and Women's Hospital (Boston, MA); and Joseph Vinetz, Travel Clinic, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, University of California-San Diego School of Medicine (La Jolla, CA).

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Footnotes

Financial support: This work was supported by US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Grants U19CI000514 and U01CK000175.

Authors' addresses: Regina C. LaRocque and Edward T. Ryan, Travelers' Advice and Immunization Center, Massachusetts General Hospital and Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, E-mails: rclarocque@partners.org and etryan@partners.org. Bhushan R. Deshpande, Division of Infectious Diseases, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, and Department of Economics, Tufts University, Medford, MA, E-mail: bdeshpande@partners.org. Sowmya R. Rao, Department of Quantitative Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA, and Center for Health Quality, Outcomes, and Economics Research, Bedford Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Bedford, MA, E-mail: Sowmya.Rao@umassmed.edu. Gary W. Brunette and Emily S. Jentes, Division of Global Migration and Quarantine, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, E-mails: fvd3@cdc.gov and ejentes@cdc.gov. Mark J. Sotir, Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, E-mail: mps6@cdc.gov.

References

- 1.US Census Bureau Current Population Survey. 2012. http://www.census.gov/cps/ Available at. Accessed March 7, 2012.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . CDC Health Information for International Travel 2012. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angell SY, Cetron MS. Health disparities among travelers visiting friends and relatives abroad. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:67–72. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-1-200501040-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mali S, Kachur SP, Arguin PM. Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria; Center for Global Health; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Malaria surveillance—United States, 2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2012;61:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lynch MF, Blanton EM, Bulens S, Polyak C, Vojdani J, Stevenson J, Medalla F, Barzilay E, Joyce K, Barrett T, Mintz ED. Typhoid fever in the United States, 1999–2006. JAMA. 2009;302:859–865. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boggild AK, Castelli F, Gautret P, Torresi J, von Sonnenburg F, Barnett ED, Greenaway CA, Lim PL, Schwartz E, Wilder-Smith A, Wilson ME. GeoSentinel Surveillance Network Vaccine preventable diseases in returned international travelers: results from the GeoSentinel surveillance network. Vaccine. 2010;28:7389–7395. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leder K, Tong S, Weld L, Kain KC, Wilder-Smith A, von Sonnenburg F, Black J, Brown GV, Torresi J. GeoSentinel Surveillance Network Illness in travelers visiting friends and relatives: a review of the GeoSentinel surveillance network. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1185–1193. doi: 10.1086/507893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Askling HH, Rombo L, Andersson Y, Martin S, Ekdahl K. Hepatitis A risk in travelers. J Travel Med. 2009;16:233–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2009.00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Measles: United States, January–May 20, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:666–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LaRocque RC, Jentes ES. Health recommendations for international travel: a review of the evidence base of travel medicine. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:403–409. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32834a1aef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arguin PM, Marano N, Freedman DO. Globally mobile populations and the spread of emerging pathogens. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1713–1714. doi: 10.3201/eid1511.091426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LaRocque RC, Rao SR, Tsibris A, Lawton T, Anita Barry M, Marano N, Brunette G, Yanni E, Ryan ET. Pre-travel health advice-seeking behavior among US international travelers departing from Boston Logan International Airport. J Travel Med. 2010;17:387–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2010.00457.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamer DH, Connor BA. Travel health knowledge, attitudes and practices among United States travelers. J Travel Med. 2004;11:23–26. doi: 10.2310/7060.2004.13577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Herck K, Van Damme P, Castelli F, Zuckerman J, Nothdurft H, Dahlgren AL, Gisler S, Steffen R, Gargalianos P, Lopez-Velez R, Overbosch D, Caumes E, Walker E. Knowledge, attitudes and practices in travel-related infectious diseases: the European airport survey. J Travel Med. 2004;11:3–8. doi: 10.2310/7060.2004.13609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LaRocque RC, Rao SR, Lee J, Ansdell V, Yates JA, Schwartz BS, Knouse M, Cahill J, Hagmann S, Vinetz J, Connor BA, Goad JA, Oladele A, Alvarez S, Stauffer W, Walker P, Kozarsky P, Franco-Paredes C, Dismukes R, Rosen J, Hynes NA, Jacquerioz F, McLellan S, Hale D, Sofarelli T, Schoenfeld D, Marano N, Brunette G, Jentes ES, Yanni E, Sotir MJ, Ryan ET. the Global TravEpiNet Consortium Global TravEpiNet: a national consortium of clinics providing care to international travelers—analysis of demographic characteristics, travel destinations, and pretravel healthcare of high-risk US international travelers, 2009–2011. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:455–462. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The World Bank . World Development Report 2009: Reshaping Economic Geography. Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . CDC Health Information for International Travel 2010. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schlagenhauf P, Chen LH, Wilson ME, Freedman DO, Tcheng D, Schwartz E, Pandey P, Weber R, Nadal D, Berger C, von Sonnenburg F, Keystone J, Leder K. GeoSentinel Surveillance Network Sex and gender differences in travel-associated disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:826–832. doi: 10.1086/650575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Travel and Tourism Statistics, International Trade Administration, Office of Travel and Tourism Industries, US Department of Commerce 2011. http://tinet.ita.doc.gov/outreachpages/outbound.general_information.outbound_overview.html Available at. Accessed March 7, 2012.

- 20.Hagmann S, Neugebauer R, Schwartz E, Perret C, Castelli F, Barnett ED, Stauffer WM. GeoSentinel Surveillance Network Illness in children after international travel: analysis from the GeoSentinel surveillance network. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e1072–e1080. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen LH, Wilson ME, Davis X, Loutan L, Schwartz E, Keystone J, Hale D, Lim PL, McCarthy A, Gkrania-Klotsas E, Schlagenhauf P. GeoSentinel Surveillance Network Illness in long-term travelers visiting GeoSentinel clinics. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1773–1782. doi: 10.3201/eid1511.090945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacquerioz FA, Croft AM. Drugs for preventing malaria in travellers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;4:CD006491. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006491.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schlagenhauf P, Adamcova M, Regep L, Schaerer MT, Rhein HG. The position of mefloquine as a 21st century malaria chemoprophylaxis. Malar J. 2010;9:357. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]