Abstract

It has become increasingly widely recognized that the stroma plays several vital roles in tumor growth and development and that tumor-stroma interactions can in many cases account poor therapeutic response. Inspired by an emerging body of literature, we consider the potential role of photodynamic therapy (PDT) for targeting interactions with stromal fibroblasts and mechano-sensitive signaling with the extracellular matrix as a means to drive tumors toward a more therapeutically responsive state and synergize with other treatments. This concept is particularly relevant for cancer of the pancreas, which is characterized by tumors with a profoundly dense, rigid fibrous stroma. Here we introduce new in vitro systems to model interactions between pancreatic tumors and their mechanical microenvironment and restore signaling with stromal fibroblasts. Using one such model as a test bed it is shown here that PDT treatment is able to destroy fibroblasts in an in vitro 3D pancreatic tumor-fibroblast co-culture. These results and the literature suggest the further development of PDT as a potential modality for stromal depletion.

1. Introduction

An accelerated pace of discovery in cancer research over the course of the past decade has given rise to an increasing armamentarium of therapeutic targets under investigation in the laboratory and the clinic.1,2 At the same time our appreciation of the complexity of the disease has also increased and broadened to encompass physical and mechanical influences outside the scope of traditional thinking in cancer biology.3,4 Interactions with the mechanical properties of extracellular matrix, though elegantly described in a variety of normal tissues5 has more recently been given due consideration specifically as it impacts mechnanosensitive signaling of cancer cells6,7 and may further serve as a physical barrier to drug penetration in the tumor.8,9 Additionally, number of studies have elevated recognition of the importance of heterotypic communication between cancer cells and fibroblasts,10–15 and other stromal partners.16,17 Collectively, these insights point to the critical role of tumor-stroma interactions as determinants of tumor growth, development and therapeutic response and have inspired numerous preclinical and clinical investigations directly addressing the stroma as a therapeutic target.18–21

The emerging importance of tumor-stroma interactions in cancer therapy raises the possibility of investigating the potential role for photodynamic therapy (PDT) in this capacity. PDT is a light-based therapeutic modality in which wavelength specific activation of a photosensitizing molecule (photosensitizer, PS) imparts cytotoxicity to target tissues for treatment of both cancer and non-cancer pathologies.22,23 In PDT treatment of solid tumors, the PS is administered and allowed to accumulate (either passively or via an active targeting mechanism23) in the malignant tissue prior to site-specific light activation to generate cytotoxic species, most notably via intersystem crossing to produce singlet oxygen (1O2). While PDT has been extensively evaluated both pre-clinically and clinically for the treatment of a variety of cancers,24 the concept of leveraging PDT to attack the tumor stroma in order to counteract therapeutic resistance induced by stromal signaling is an approach which has not been explored.

In this article we briefly review recent literature that has provided basic insights into the role of tumor-stroma interactions as determinants of tumor growth behavior and treatment response and introduce new in vitro model systems to study these interactions in a manner that is conducive to interrogation by imaging. A growing number of studies indicate that PDT can impact upon tumor-stroma interactions in a variety of capacities, either acting directly on the extracellular matrix, receptors involved in matrix signaling, or in other capacities to interrupt stromal signaling.

It has been reported in several contexts that the physical properties of a cell’s microenvironment, including the rheology of the surrounding extracellular matrix, can regulate biochemical signaling and phenotype. 3,6,25–29 For example, the lineage commitment of mesenchymal stem cells to either adipocyte or osteoblast has been shown to be regulated by mechanical cues from the extracellular environment.27 Elegant mechanistic studies have provided insight into the mechanosensitive signaling pathways which regulate such interactions by which growth and differentiation is influenced by extracellular stiffness.5,30,31 However, while it is well recognized that tumors tend to be stiffer than normal tissue, and this fact can even be leveraged for diagnostic imaging,32 the complex set of interactions through which the physical rigidity of the extracellular environment can be involved in driving malignancy and influencing the behavior of cancer cells is less well understood. In fact, the development of an exceptionally stiff extracellular matrix as part of the desmoplastic response, through which stromal fibroblasts, in communication with cancer cells, produce an overabundance of collagen associated with several tumors.33–37 However, the role of this characteristic desmoplasia remains unclear. Some have suggested that the development of this collagen-rich rigid stroma may have a protective effect by preventing invasion38,39 while a number of studies indicate that increased matrix rigidity plays a role in promoting motility and invasiveness of tumor cells,39,40 and in fact a higher tumor stiffness has been correlated with poor prognosis.41,42 An elegant study by Paszek et al shed light on the role mechanical interactions between tumors and ECM by systematically examining the growth of mammary epithelial cells on substrates of varying rigidity to show that matrix mechanics act as a regulator of growth, morphogenesis and integrin mediated adhesions.6 While normal MEC’s grown on ECM of physiological stiffness form normal three-dimensional acini, the same cells are cultured on a more rigid substrate, with elastic modulus close to that of tumor stroma, begin to exhibit signs of tumorigenic behavior. This work, and other recent studies point to the conclusion that the elevated matrix rigidity around tumors driven by the desmoplastic response, leads to increased cytoskeletal tension, disruption of normal tissue polarity, and more characteristically malignant behavior.

The integrin family of heterodimeric transmembrane receptors are a crucial player in connecting extracellular matrix mechanics to downstream signaling, and play a particularly diverse set of roles in cancer.43,44 Integrins consist of an extracellular domain which acts as a ligand binding site for ECM proteins such as collagen, laminin, fibronectin and vitronectin, and an intracellular domain which, with the cooperation of other proteins such as talin and vinculin, connects to the cytoskeleton and serves as a key mechanical linkage for transmission of extracellular cues to intracellular signaling. For example in the study of Paszek et al, which is referenced above, enhanced ERK activation in cells grown on a matrix with elevated rigidity occurs downstream of integrin clustering, which is induced by contact with a rigid ECM.6 Thus integrin signaling serves as the key link connecting matrix rigidity to changes in tumor behavior. More broadly, integrins in cancer cells associate with other receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK) to regulate invasion and metastasis, and extensive literature exists discussing the role of integrins in cancer survival and proliferation.43,44

In light of these roles for integrins in cancer, the potential role for PDT in disrupting integrin signaling is especially promising. Runnels et al showed that a low dose of PDT with benzoporphyrin derivative monoacid ring A (BPD) caused loss of function of the critical β1-integrin sub-units.45 This integrin sub-unit and certain B1-containing integrin heterodimers have been specifically associated with increased metstasis and poor prognosis.46–49 In the context of this study the ability of PDT to interrupt integrin signaling suggests that it may interrupt a key component of therapeutically problematic mechanosensitive signaling. This could be partly responsible for a recently reported observation that pancreatic cancer cells adherent to a bed extracellular matrix become markedly less sensitive to treatment with gemcitabine than cells grown in traditional monolayer cell culture, while the presence of ECM has minimal impact on the efficacy of PDT treatment.50 Other studies have further indicated the ability of PDT to decrease adhesion to other substrates. Uzdensky et al showed that ALA-induced PpIX photosensitization prevented human adenocarcinoma cells in suspension from adhering to a plastic substrate concomitant with increased ανβ3 focal contacts.51 Volanti et al demonstrated the ability of PDT to down-regulate the expression of the adhesion factors ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 in endothelial cells.52 Relatedly, other studies showed adhesion of cancer cells to the endothelium is diminished following PDT.53,54 Other examples of the impact of PDT on integrins and other adhesion molecules are reviewed by Pazos et al.

In addition to the extracellular matrix itself, critical tumor-stroma interactions which regulate tumor progression involve multiple channels of communication between cancer cells and stromal fibroblasts.10,39,55,56 A population of fibroblasts known as cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are particularly implicated for promoting tumor progression by stimulating survival and proliferation signaling pathways in through heterotypic signaling with cancer cells.57 For example, stromal myofibroblasts have been shown to infiltrate colon cancer during tumor invasion.58 Indeed, in the case of pancreatic cancer, noted for its particularly profound stromal reaction, interaction with pancreatic stellate cells, myofibroblast-like cells of the exocrine pancreas, has been described as an “unholy alliance.”16 Through interactions mediated by ECM proteins, transforming growth factor B1 (TGFB1), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and other secreted factors, PSCs have been shown to increase proliferative signaling, decrease apoptosis and increase migration and invasion in pancreatic cancer cells. Conversely, pancreatic cancer cells promote increased proliferation, ECM production and migration of PSCs.16 Interaction with stromal fibroblasts has also been shown to promote treatment resistance. Hwang et al showed that supernatant containing secreted factors from cultures of PSCs promoted mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) and Akt signaling pathways and decreased efficacy of gemcitabine and radiation therapy when added to cultures of pancreatic cancer cells.57 Similarly, in the same study, orthotopic co-implantation of PSCs and pancreatic cancer cells in a murine model produced increased incidence of tumor incidence size and metastasis relative to implantation of pancreatic cancer cells alone. Interaction with stromal fibroblasts has also been shown to increase the invasiveness of pancreatic cancer cells, a behavior, which interestingly, was noted to be increased in the presence of fibroblasts that had been previously treated with radiotherapy.59 These studies point overwhelmingly to the conclusion that fibroblasts play multiple key roles in tumor progression and treatment resistance, and must be considered as an important target for cancer therapies.

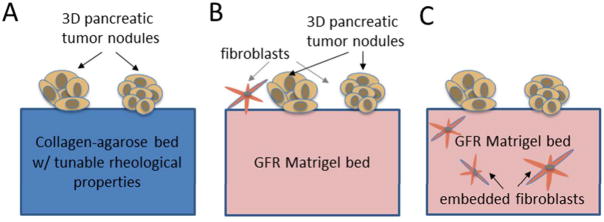

Guided by insights from the aforementioned literature, this study introduces in vitro 3D tumor models and tumor-fibroblast co-culture models that restore the critical interactions described above, as a means for mechanistic evaluation of PDT-based regimens targeting the tumor stroma. As noted above, this approach is especially relevant in the case of pancreatic cancer, for which tumor-stroma interactions have been noted to play a particularly prominent role.33,60 Indeed for this disease, the concept of stromal depletion to enhance drug penetration is currently under exploration in clinical studies.18 For these reasons, the in vitro model systems introduced here are based on pancreatic cancer cells, though it is likely that the insights here could be generally more broadly to other tumors, particularly those noted above for a characteristic desmoplastic response. In this study we further go on to examine response to PDT in a pancreatic cancer-fibroblast co-culture model and use an imaging-based methodology for treatment assessment to examine cytotoxic response in each population.

2. Experimental Section

In vitro three-dimensional (3D) pancreatic tumor models on collagen-agarose beds

In vitro three-dimensional cultures of PANC-1 pancreatic cancer cells were prepared by overlaying cells on model stromal beds composed of mixtures of collagen and agarose. PANC-1 cells were obtained from the American Type Cell Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, Maryland, USA), grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in standard tissue culture conditions and harvested for 3D culture plating by trypsinization. Media and FBS were obtained from Mediatech (Herndon, VA, USA) and Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA), respectively. All media was supplemented with 50 IU/ml penicillin and 50 mg/ml streptomycin (Mediatech). The overlay 3D culture geometry depicted in Figure 1A is similar to a geometry previously described for a variety of cell lines with the notable exception of the selection of the underlying matrix bed material used here. Collagen-agarose beds were adopted for as a substrate suitable for adherent cell growth with tunable mechanical properties by variation of agarose content, and prepared according to the protocol introduced by Ulrich et al.61 Briefly, collagen-agarose beds were prepared by first preparing a mixture of chilled Type I bovine collagen (BD Biosciences, USA) and DMEM to a concentration of 2.0mg/mL collagen, and adding 1M NaOH dropwise to adjust pH of mixture to 7.4. Solutions of 2% w/v low melting temperature agarose(A9414, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) were prepared by dissolving agarose in DMEM. This solution was then elevated to 95C, divided into smaller volumes and diluted accordingly in DMEM to double the concentration of each of the final desired agarose concentrations (0.25% w/v, 0.5% w/v, and 1.0% w/v). The agarose-collagen solutions were then combined and pipetted into the wells of 24-well black walled glass bottom culture plates (Greiner BioOne) and incubated at 37C. After allowing collagen-agarose beds to set thoroughly for 1 hour, PANC-1 cells were harvested via trypsinization and resuspended into single cell suspension in DMEM containing 2% GFR Matrigel and overlaid on collagen agarose beds. Cultures were returned to the incubator taking care to avoid agitation and allowed to adhere and spontaneously form 3D nodules as previously described for cells overlaid on GFR Matrigel.62,63

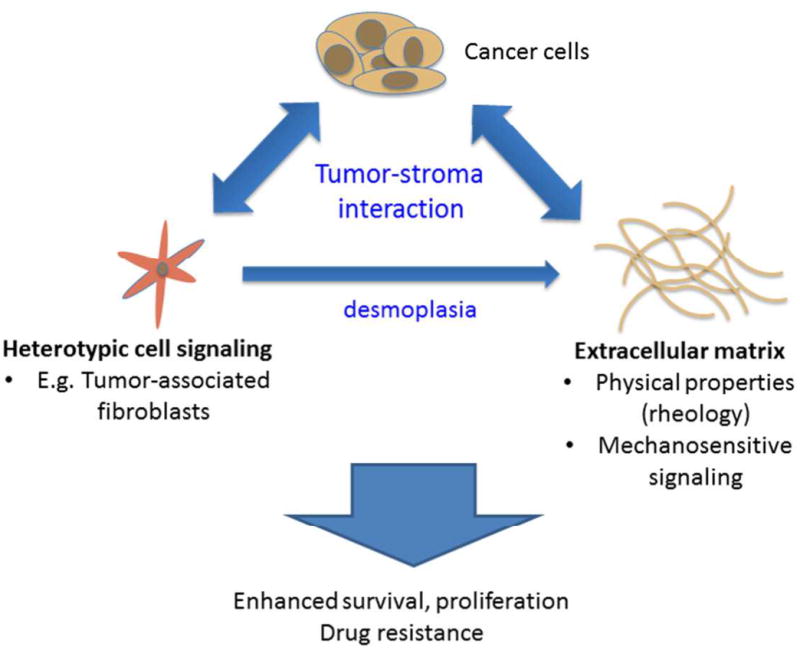

Figure 1.

A highly simplified schematic representation of the tumor-stroma interactions discussed herein that give rise to potentially treatment-resistant tumors. Here we specifically discuss heterotypic signaling between cancer cells and stromal fibroblasts and their role in the desmoplastic response that is seen in many solid tumors. The extracellular matrix, (ECM) which is produced in over-abundance due to this response also serves as a signaling partner via mechanosensitive signaling which can serve as a regulator of proliferation, invasion and survival via integrin-mediated signaling.

In vitro 3D pancreatic tumor-fibroblast co-cultures

In this study, two variations of cancer-fibroblast co-cultures were prepared as shown schematically in Figure 1B and 1C. In both cases, the fibroblast cell lines used is MRC-5 normal human fibroblasts (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA). In one case MRC-5 cells were overlaid onto a bed of Growth Factor Reduced Matrigel (GFR Matrigel, BD Biosciences) in the same plane as 3D nodules which formed from PANC-1 cells plated on the bed 7–10 days earlier (Figure 1B) adopting a variation on a geometry previously explored for ovarian cancer co-cultures.11 In the other scenario, shown in Figure 1C, MRC-5 fibroblasts were mixed into the GFR Matrigel prior to pipetting the fibroblast -containing GFR Matrigel solution into the multiwell plate to form the underlying stromal bed. In both cases Matrigel (BD Biosciences) was pipetted into the wells of a chilled 24-well glass bottom black-walled culture plate (Greiner BioOne) and allowed to polymerize at 37°C to form a soft viscoelastic gel prior to overlaying PANC-1 cells in single cell suspension resuspended to a concentration of 15,000 cells/mL in complete medium containing 2% GFR Matrigel.

Rheology measurements

For mechanical characterization of collagen-agarose composite beds, a TA instruments AR-G2 stress-controlled rheometer (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA) equipped with a 40 mm parallel plate geometry, was used. The rheometer was fitted with a peltier plate to regulate the sample temperature to 37.0°C in all tests reported here. In all cases, an initial stress sweep with an oscillatory shear stress of increasing amplitude at a constant angular frequency, ω, of 1.0 rad/s was performed to identify an applied stress within the linear regime to be used in subsequent frequency sweeps to obtain the complex viscoelastic shear modulus, G*(ω)=G′(ω) + iG″(ω) over 0.1 < ω < 10 rad/s.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT)

PDT treatments described here were performed using the photosensitizer benzoporphyrin derivative monoacid ring-A (BPD), commonly known as verteporfin. This study specifically used the liposomal formulation of this agent for clinical use (trade name Visudyne) obtained from Quadra Logic Technologies (QLT Inc., Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada). Quoted concentrations were confirmed by UV-Vis absorption measurements based on well-characterized optical properties of this compound.64 PDT treatments in pancreatic cancer and pancreatic cancer-fibroblast co-cultures were performed by laser irradiation at 690nm following a 90-minute incubation with a 1 μM concentration of BPD. In all cases, media containing BPD was replaced with regular culture media immediately prior to laser irradiation. Irradiation of individual 3D culture treatment groups within black-walled multiwell plates at a fluence rate of 100 mW/cm2 was administered through the glass bottom of each well by a vertically mounted fiber coupled to the 690nm laser diode source (Model 7401, Intense, North Brunswick, NJ, USA) as previously described.63 Following BPD-based PDT treatment, cultures were returned to the incubator for 24 hours prior to evaluation.

Imaging-based growth characterization

All quantitative characterization of in vitro 3D growth and treatment assessment is based on methods previously described.62 Briefly, characterization of nodule size-distributions were obtained from 5X darkfield microscopy snapshots from the central region of each culture well where the ECM bed meniscus contour is minimal. Imaging was conducted using a Zeiss Axiovert inverted microscope equipped with a 12-bit cooled monochrome digital camera with a 2048 by 2048-pixel chip providing a field of view of approximately 3mm by 3mm. Image processing to obtain size distributions from sets of images obtained from each condition at each timepoint was conducted in Matlab software using custom batch routines to segment images and output size data for each nodule. Equivalent diameter (deq) is reported as the diameter (in μm) of a circular area equal to the area of that nodule in the image plane (in μm2). Phase contrast timelapse sequences were obtained using a Nikon Eclipse microscope in an enclosed weatherstation, with a 10X objective.

Imaging-based PDT Treatment Assessment in 3D cultures

Cytotoxic response following PDT treatments was analyzed by a method for ratiometric quantification of calcein AM and ethidium bromide (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) fluorescence signals which act as reporters of live dead cells respectively described extensively in previous studies.62,63,65 Fluorescence images were obtained in multiwell plates using an Olympus FV-1000 confocal microscope with an automated XY positioning system to scan over each well and acquire images from each of the two fluorescence channels and through a transmitted light detector. Calcein was excited with the 488nm line from an argon ion laser while ethidium was excited with a 559nm laser diode. Images were acquired with a 4X objective to obtain large fields of view and collect light over a large depth of focus with pinhole set to 550um to effectively integrate fluorescence signal over as large an extent of nodule depth as allowed by light penetration in a single plane. Quantitative results were obtained as follows (briefly): The ratio of the calcein signal to the total signal was measured for each treatment group and normalized to the no treatment control to report normalized viability. Combining the ratiometric intensity-based quantification from the fluorescence signals with the segmentation-based analysis of the live channel further provides cytotoxic response for each individual nodule. In fibroblast co-cultures in which nodules were in a different z-plane than the underlying fibroblasts (as shown in Figure 1C), the fluorescent signal in all groups and controls is collected only from the cancer-cell containing planes. Three-dimensional z-stacks to show qualitative differences in killing in different planes were obtained with a 10X objective with a z-resolution 5μm. Confocal slices were extracted for presentation in the freely available ImageJ software.

3. Results and Discussion

Influence of matrix rigidity on multicellular pancreatic micronodules in vitro

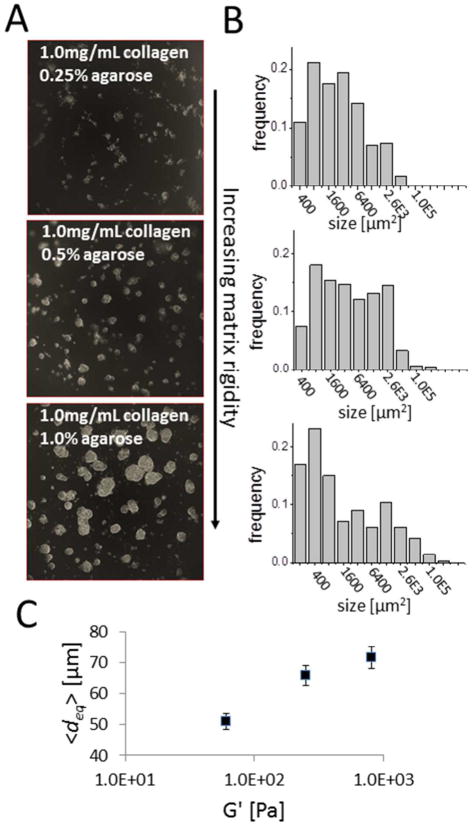

Motivated by the noted rigidity of pancreatic tumor stroma in vivo, we sought to develop an in vitro pancreatic tumor model system in which the growth properties of 3D tumor nodules could be examined as a function of the extracellular matrix rigidity. Adopting an overlay geometry which is conducive to interrogation by imaging, PANC-1 pancreatic cancer cells were overlaid on matrix beds consisting of a collagen-agarose mixture (shown schematically in Figure 2A). This matrix bed, characterized extensively by Ulrich et al, provides the ability tune rheological properties by variation of agarose content while holding the concentration of collagen constant and with little or no variation in the structure of the collagen gel.61 PANC-1 tumor nodules spontaneously formed within 5 days from overlaying single-cell suspensions on the collage-agarose beds. As shown in representative darkfield snapshots of nodules from the central region of each well, acquired at day 5 after plating (Figure 3A), there is a profound dependence in the size of nodules on the amount of agarose incorporated into the matrix bed, with higher agarose content producing a more rigid matrix. The size distributions of nodules formed in each condition (Figure 3B), as obtained by automated segmentation to get the size of each nodule in each condition, systematically shifts to the right (toward larger sizes). Size distributions appear to agree with the bi-modal lognormal form previous reported for in vitro 3D nodules formed from cells overlaid on a GFR Matrigel substrate.62 Plotting the mean nodule diameter (over 3 repeats of each condition) against measurements of the real term (G′) of viscoelastic shear modulus of the three matrix bed conditions (measured at an oscillatory frequency of ω=1 rad/s) created here shows that a more rigid underlying matrix leads to larger nodule sizes (Figure 3C). This result is qualitatively consistent with a previous report that colony size of mammary epithelial cells increases with increasing stiffness of the underlying collagen bed,6 though in the present case stiffness of the bed is modulated without varying collagen content.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of in vitro 3D tumor model systems in this study. In (A) pancreatic cancer cells are overlaid on a model extracellular bed which consists of a collagen-agarose mixture.

Figure 3.

Rigidity of extracellular matrix bed as a determinant of in vitro three-dimensional pancreatic tumor nodule growth properties. (A) In representative darkfield snapshots of nodules from the central region of each well, acquired at day 5 after plating, there is a profound dependence in the size of nodules on the amount of agarose incorporated into the matrix bed, with higher agarose content producing a more rigid matrix. (B) The size distributions of nodules formed in each condition, systematically shifts to the right (toward larger sizes) with increasing agarose content as suggested by the images in (A). In (C) plots of mean nodule diameter against measurement of the viscoelastic shear modulus of the three matrix bed conditions created here shows that a more rigid underlying matrix leads to larger nodule sizes

These results speak to the relevance of matrix stiffness as a parameter for modulating growth properties of in vitro pancreatic tumors though additional characterization is warranted. For example, it is unclear to what extent nodule size is increased by co-migration and cell-cell adhesion62 versus increases in size due to increased proliferation. It also remains to be seen whether the rigidity dependent behavior observed here is associated with increased integrin adhesions, or if partly a result of an increased rate of co-migration, then if it is primarily increased motility on a more rigid substrate which drives increased nodule size. In either case, the impact of matrix rigidity on nodule formation and growth, combined with the ability of PDT to modify matrix properties,13 suggests the plausibility of using PDT to drive the matrix to conditions that would promote smaller, more manageable nodules.

Restoring stromal interactions in tumor-fibroblast co-cultures

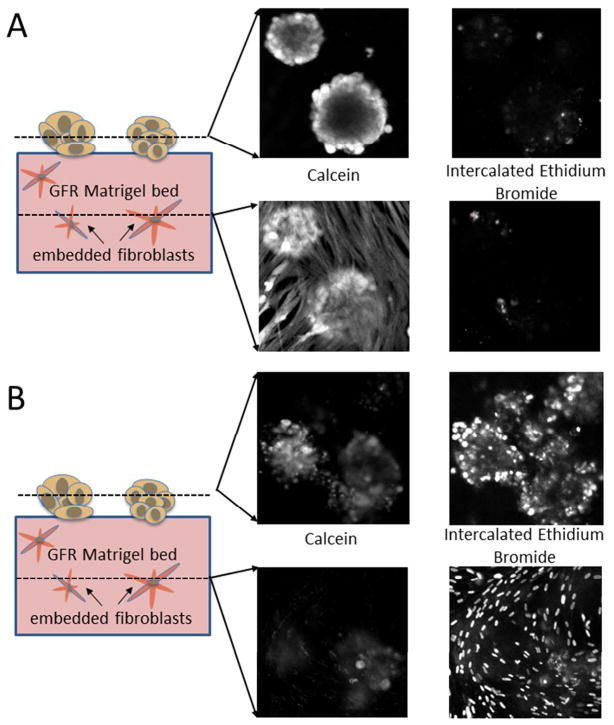

To explore another avenue in restoring stromal interactions, co-cultures were developed to introduce normal human fibroblasts as signaling partners either within the underlying matrix bed, or overlaid on top of the matrix bed, in the same plane as the tumor nodules (as shown schematically in Figure 2B and 2C respectively). In both cases, for this exploration of heterotypic interactions, the robust and extensively characterized commercial ECM product, GFR Matrigel (BD Biosciences, MA, USA), was used to focus the number of new parameters and create growth conditions known to be suitable for the culture of both cell types. We first discuss the scenario illustrated schematically in Figure 2B, in which fibroblasts were overlaid in the same plane as in vitro tumor nodules.

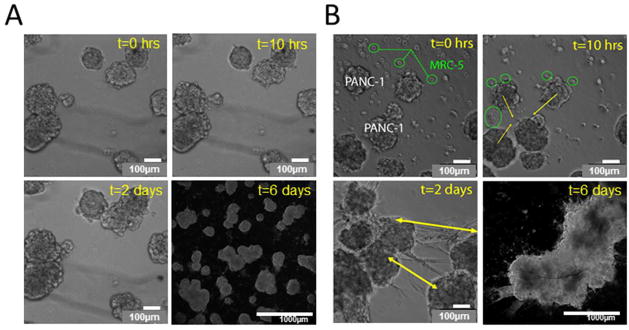

As shown in Figure 4, there are marked difference in growth behavior in PANC-1 3D cultures in the presence of absence of overlaid fibroblasts. In the absence of fibroblasts, individual nodules continue to grow larger via cell proliferation to within a range of roughly 200 – 500um, but at this stage of growth nodules remain largely non-interacting as shown in Figure 4A for timelapse snapshots of the same field beginning at day 12 from the time of initial plating of the cells. (Note: t = 0 is defined with respect to the time of fibroblast addition in respective groups, or in the non-fibroblast controls, the time of a sham media substitution. When MRC-5 fibroblasts are introduced into these culture they initially adhere to the matrix bed as single cells as shown in Figure 4B. As seen in the t=10hrs snapshot, there is an extremely rapid migration of fibroblasts and collective movement of multicellular PANC-1 nodules towards each other within this time frame. Simultaneously, the fibroblasts undergo a rapid change into a myofibroblast-like morphology, forming long spindles and interconnecting into networks that span between individual PANC-1 nodules that are initially spatially separated. This interaction reproducibly leads to formation of millimeter sized intermingled PANC-1/MRC-5 co-cultures within 6 days after incorporation of MRC-5 as shown in the lower magnification darkfield image (Figure 4B, t=6 days). Representative timelapse and darkfield snapshots shown in Figure 4 are typical of observations repeated in triplicates of each condition (with and without fibroblasts) in two independent experiments.

Figure 4.

Comparison of late stages of in vitro 3D tumor nodule formation process in the absence (A) and presence (B), of MRC-5 normal fibroblasts overlaid on a GFR Matrigel bed with PANC-1 3D nodules. In (A) continued monitoring of the growth of 3D nodules in the same microscopic field is shown from day 12 onwards in the absence of fibroblasts. Time stamps at 0 hours, 10 hours and 2 days show change in time relative to a sham media substitution (not containing fibroblasts)in the same field. The image for t=6 days (day 18 total growth) was obtained by darkfield microscopy and zoomed out to capture a larger field of view showing that separate nodules continue to enlarge via proliferation but remain largely spatially separated over the field of view. In (B) timelapse images of MRC-5 fibroblasts seeded onto Matrigel beds containing PANC-1 3D nodules is shown for the same timepoints as in (A). MRC-5 fibroblasts rapidly adhere to the matrix bed as single cells (green circles) and rapidly co-migrate to form connected networks that span regions between tumor nodules (green arrows at t=2 days) and exert contractile forces to induce aggregation. This interaction leads to formation of millimeter sized co-cultures 6 days after incorporation (shown at 5X magnification with 1mm scale bar).

It is clear from these experiments that there is profound interaction between these two cell populations. The large heterogeneous fibrous nodules which are formed as a result of the interactions modeled here provide a potentially rich model system to recapitulate the physiological pancreatic tumor microenvironment. These millimeter scale fibrous nodules could indeed prove to be an interesting test-bed to evaluate the effect of therapeutics focused on the therapeutic paradigm of enhancing drug penetration in rigid hypovascular pancreatic tumors. While this model system is undergoing further development and characterization, it proves to be challenging to use as a robust tool for PDT treatment assessment without the ability to distinguish between the two cell populations after they have formed densely mingled masses. This could be overcome by incorporation of fluorescently labeled populations (using, for example, green fluorescent protein, and red fluorescent protein-expressing mutants) or to allow for assessment of distinct cytotoxicity in the two populations by co-localization of viability/death and cell-type specific fluorescent labels.

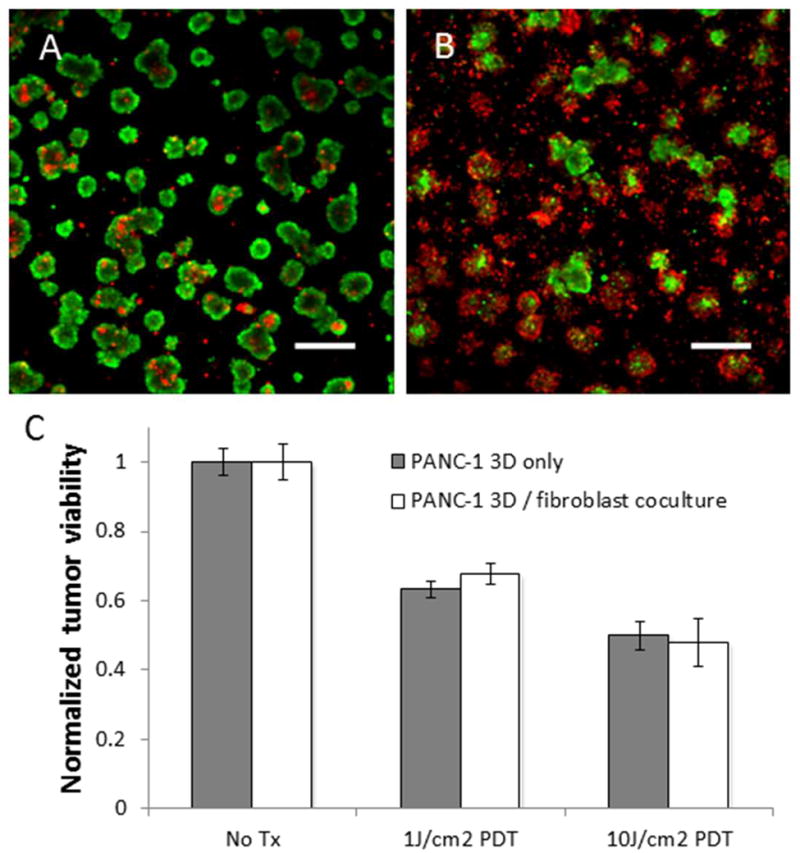

In the present study it was desirable to develop a co-culture model in which the two cell populations could be in communication while spatially separated to allow for assessment of treatment effect in each cell type by optical microscopy. Towards this end, co-cultures in which fibroblasts were embedded in the ECM bed underneath tumor nodules were developed (as shown schematically in Figure 2C). In this geometry, the fibroblast and cancer cell populations are in proximity to allow communication but can be imaged separately. Formation of in vitro 3D nodules on the bed followed similar kinetics resulting in formation of distinct micronodules, with strong calcein (green) signal indicative of high esterase in cells stained with calcein acetoxymethylester, and evidence of only a few dead or dying cells (likely due to poor nutrient and oxygen diffusion to the center of larger nodules) indicated by the standard fluorescent counterstain for dead cells, ethidium bromide (red), as shown in Figure 5A. Upon treatment with verteporfin-based PDT, with a total fluence delivered of 10J/cm2 at 690nm, there is significant cell killing in the 3D nodules clearly observable in Figure 5B with strong ethidium bromide staining in most nodules. Verteporfin-based PDT treatments were conducted at 1J/cm2 and 10J/cm2 total fluence (both following 1uM BPD incubation for 90 minutes prior to irradiation) and in sets of cultures with MRC-5 fibroblasts present and absent. Importantly, there is no evidence of any significant difference in overall cytotoxic response in 3D nodules that are in the presence or absence of fibroblasts at either PDT dose probed (Figure 5C). This result stands in contrast to previous studies, as discussed above, which have shown that co-cultures with cancer cells and fibroblasts have diminished sensitivity to radiation and chemotherapy relative to cultures of cancer cells alone.57

Figure 5.

BPD PDT response in PANC-1 3D nodules prepared via overlay on a model stromal bed consisting of GFR Matrigel with embedded fibroblasts compared to PANC-1 3D nodules on a GFR Matrigel bed containing no fibroblasts. (A) A representative field of in vitro 3D nodules in the no-treatment group stain brightly with calcein (green) and with few dead cells (red). In (B) a representative field from cultures treated with BPD-PDT (1μM BPD with 10J/cm2 total light dose) shows nearly cytotoxic response as evidenced by an increased proportion of nodules emitting strong fluorescence signal from intercalated ethidium bromide. Both representative treatment snapshots are shown for the co-culture groups, but in the focal depth of the PANC-1 nodules, there is no discernible difference between the culture groups as out of plane light from the lower focal plane of the embedded fibroblasts is completely rejected. Scale bars in A and B are 500μm. Quantitative results shown in (C) report normalized viability from analysis of complete sets of fluorescence image data for co-cultures and cultures of pancreatic cancer cells only for each treatment group (no treatment, and 1μM BPD incubation followed by 1J/cm2 and 10J/cm2 total light doses respectively). Results indicate that there is no significant difference in the cytotoxic response of the 3D pancreatic tumor nodules whether or not there are fibroblasts present in the underlying stromal bed.

To examine the distinct cytotoxic response of PANC-1 cancer cells and MRC-5 fibroblasts in this experimental geometry, confocal z-stacks of cultures stained with calcein AM and ethidium bromide were obtained (Figure 6). In the absence of any treatment, both populations are highly viable, with strong calcein green fluorescence emission as expected in the representative snapshots for each fluorescence channel in each z-plane as shown in Figure 6A, left. Similarly, the channel corresponding to fluorescence emission from intercalated ethidium bromide shows only a few punctate spots. The calcein stain in the lower z-plane of the untreated cultures shows the extended morphology of fibroblasts embedded inside the gel, similar to what we observe at intermediate timepoints in the alternate overlaid geometry in which fibroblasts are on top of the gel. This morphology is generally consistent with the model of a dense fibrous stroma which these in vitro models are intended to recreate. It is also evident that the tumor nodules on the surface of the gel bed do partially invade into the underlying stromal bed, an effect which may be enhanced by the presence of fibroblasts in the bed.15 The significance of the demonstrated ability of PDT to destroy stromal fibroblasts in this model system, remain to be characterized more comprehensively, though the body of evidence presented in the literature cited herein suggests that we could expect diminished invasiveness and elevated sensitivity to subsequent intervention of the surviving tumor nodule populations following eradication of the fibroblasts.

Figure 6.

Depth-resolved confocal imaging of cytotoxic response in representative untreated 3D PANC-1 fibroblast co-cultures (A), and PDT-treated co-cultures (B). In (A), the calcein (which labels viable cells) and ethidium bromide (dead cells) fluorescence images for the no-treatment control co-cultures are shown for confocal optical sections in the upper plane, containing the 3D pancreatic nodules, and the lower plane showing the fibroblasts. Both cell populations in the no treatment group are highly viable and exhibit strong fluorescence signal from the calcein channel with evidence of only a few dead or damaged cells in the ethidium bromide. The distinct cell populations are clearly evident in the calcein fluorescence channels from the circular nodular structures in the upper plane and the extended fibroblasts in the lower plane. Note that the bottoms of the 3D PANC-1 nodules do extend into the lower optical section at roughly the same z-position as the fibroblasts. In (B), analogous depth-resolved images from co-cultures treated with BPD-PDT (1μM BPD with 10J/cm2 total light dose). In the upper z-plane there is a weakened calcein signal reflective of partial PDT-induced destruction of in vitro 3D nodules (see Figure 5 for quantification) and evidence of significant cell death in the ethidium bromide channel. The lower focal depth exhibits virtually no signal in the calcein channel and punctate dots corresponding to fibroblast nuclei indicative of complete killing of fibroblasts in the stromal bed.

4. Conclusions

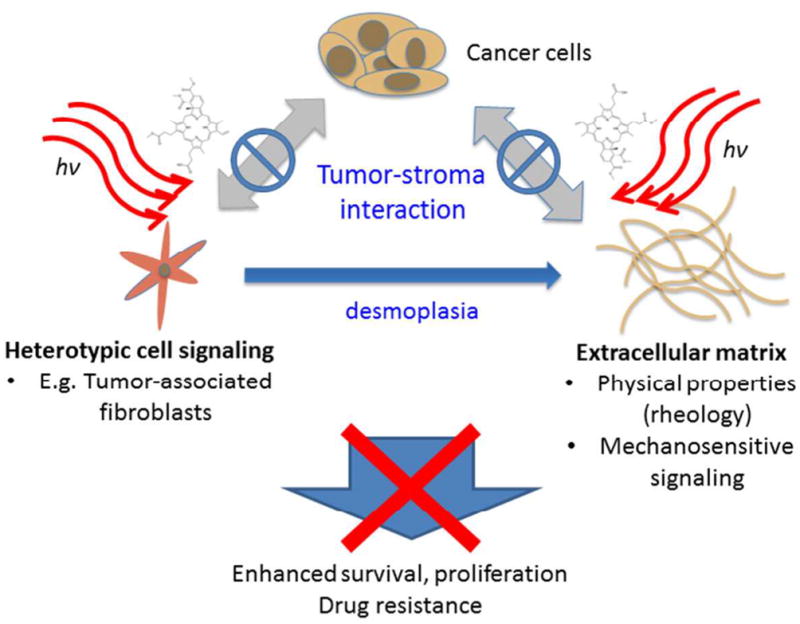

In this study we explore the use of in vitro co-culture models recapitulating tumor-stroma interactions as a platform to evaluate the impact of PDT treatment on tumor stroma. Using these models reveals the that PDT with BPD can destroy stromal fibroblasts and that PDT efficacy is not influenced by the presence of this important signaling partner which has been shown to impart therapeutic resistance in other cases. This observation combined with the body of literature cited herein, collectively makes the case for exploring PDT-based regimens for targeting the tumor stroma, or “photodynamic stromal depletion.” It is also important to note that the results reported here were achieved with non-targeted PDT in which photosensitizer was available for uptake by both cell populations. In complex tissue environments one could imagine using targeting strategies, such as that employed by Lo et al, in which a photodynamic molecular beacon was conjugated to a peptide sequence specific for fibroblast activation protein (FAP) for selective tumor imaging,66 (though the same principle could be adopted for the therapeutic approach described here). This approach could be particularly relevant for pancreatic cancer, for which PDT has already been shown to be a feasible and potentially promising new therapeutic option in early clinical trials.67 A schematic representation of the potential role of PDT in targeting the tumor stroma is illustrated in Figure 7, harkening back to the concepts introduced in Figure 1.

Figure 7.

Conceptual representation of targeting tumor stroma interactions with PDT to interrupt cross talk with stromal signaling partners that give rise to enhanced tumor survival.

Several key points distinguish the proposed PDT-based strategies to attack the tumor stroma from previous and ongoing stromal depletion approaches,9,18 primarily focused on enhancing drug penetration through the stroma. While drug penetration through the stroma may indeed be a critical problem, the strategy introduced here leverages the unique ability of PDT to target stromal signaling as a regulator of invasiveness, survival, and drug resistance as shown schematically in Figure 7. By not only interrupting the integrin-based linkages through which cancer cells interact with the mechanical properties of the ECM, but potentially loosening the matrix directly, PDT could disengage mechanosensitive signals which drive the malignant phenotype. Furthermore, as demonstrated directly in this study, even in the absence of a specific targeting strategy, PDT can eradicate entire populations of stromal fibroblasts in a single treatment, thus cutting off a signaling partner that can play several roles in promoting tumor progression as discussed above. In this manner, one could imagine combination therapies in which stroma-targeted PDT could be used to known down these barriers to therapeutic efficacy prior to subsequent intervention with chemotherapy or additional rounds of PDT. Finally, this concept is particularly intriguing in light of the demonstrated ability of PDT to sensitize chemoresistant tumors,68 and synergistically enhance the efficacy of other therapies.63,69

Acknowledgments

For many thoughtful discussions throughout which the ideas discussed herein have been developed, a debt of gratitude is owed to Professor Tayyaba Hasan and Dr. Imran Rizvi of the Wellman Center for Photomedicine at Massachusetts General Hospital. This work is supported by funding from the National Cancer Institute, (U.S. National Institutes of Health), grant 7K99CA155045-02 (PI: J.P.C.)

References

- 1.Haber DA, Gray NS, Baselga J. The evolving war on cancer. Cell. 2011;145:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins I, Workman P. New approaches to molecular cancer therapeutics. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:689–700. doi: 10.1038/nchembio840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar S, Weaver VM. Mechanics, malignancy, and metastasis: the force journey of a tumor cell. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:113–127. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9173-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wirtz D, Konstantopoulos K, Searson PC. The physics of cancer: the role of physical interactions and mechanical forces in metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:512–522. doi: 10.1038/nrc3080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ingber DE. Tensegrity-based mechanosensing from macro to micro. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2008;97:163–179. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paszek MJ, et al. Tensional homeostasis and the malignant phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:241–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ingber DE. Can cancer be reversed by engineering the tumor microenvironment? Semin Cancer Biol. 2008;18:356–364. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Netti PA, Berk DA, Swartz MA, Grodzinsky AJ, Jain RK. Role of extracellular matrix assembly in interstitial transport in solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2497–2503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olive KP, et al. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling enhances delivery of chemotherapy in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Science. 2009;324:1457–1461. doi: 10.1126/science.1171362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhowmick NA, Neilson EG, Moses HL. Stromal fibroblasts in cancer initiation and progression. Nature. 2004;432:332–337. doi: 10.1038/nature03096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu F, et al. A three-dimensional in vitro ovarian cancer coculture model using a high-throughput cell patterning platform. Biotechnology Journal. 2011;6:204–212. doi: 10.1002/biot.201000340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalluri R, Zeisberg M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrc1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pazos MC, Nader HB. Effect of photodynamic therapy on the extracellular matrix and associated components. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2007;40:1025–1035. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2006005000142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fungaloi P, et al. Platelet adhesion to photodynamic therapy-treated extracellular matrix proteins. Photochem Photobiol. 2002;75:412–417. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2002)075<0412:patptt>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kenny HA, Krausz T, Yamada SD, Lengyel E. Use of a novel 3D culture model to elucidate the role of mesothelial cells, fibroblasts and extra-cellular matrices on adhesion and invasion of ovarian cancer cells to the omentum. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:1463–1472. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vonlaufen A, et al. Pancreatic stellate cells and pancreatic cancer cells: an unholy alliance. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7707–7710. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burleson KM, et al. Ovarian carcinoma ascites spheroids adhere to extracellular matrix components and mesothelial cell monolayers. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;93:170–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garber K. Stromal depletion goes on trial in pancreatic cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 102:448–450. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loeffler M, Krüger JA, Niethammer AG, Reisfeld RA. Targeting tumor-associated fibroblasts improves cancer chemotherapy by increasing intratumoral drug uptake. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2006;116:1955–1962. doi: 10.1172/JCI26532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo Y, et al. Targeting tumor-associated macrophages as a novel strategy against breast cancer. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2006;116:2132–2141. doi: 10.1172/JCI27648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bouzin C, Feron O. Targeting tumor stroma and exploiting mature tumor vasculature to improve anti-cancer drug delivery. Drug Resistance Updates. 2007;10:109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dougherty TJ, et al. Photodynamic Therapy: Review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:889–905. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.12.889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Celli JP, et al. Imaging and Photodynamic Therapy: Mechanisms, Monitoring, and Optimization. Chem Rev. 2010;110:2795–2838. doi: 10.1021/cr900300p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hasan T, Ortel B, Solban N, Pogue B. Photodynamic therapy of cancer. In: Kufe DW, et al., editors. Cancer Medicine. B.C. Decker, Inc; Hamilton, Ontario: 2006. pp. 537–548. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butcher DT, Alliston T, Weaver VM. A tense situation: forcing tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:108–122. doi: 10.1038/nrc2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lo CM, Wang HB, Dembo M, Wang YL. Cell movement is guided by the rigidity of the substrate. Biophys J. 2000;79:144–152. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76279-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McBeath R, Pirone DM, Nelson CM, Bhadriraju K, Chen CS. Cell shape, cytoskeletal tension, and RhoA regulate stem cell lineage commitment. Dev Cell. 2004;6:483–495. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peyton SR, Ghajar CM, Khatiwala CB, Putnam AJ. The emergence of ECM mechanics and cytoskeletal tension as important regulators of cell function. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2007;47:300–320. doi: 10.1007/s12013-007-0004-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martino MM, et al. Controlling integrin specificity and stem cell differentiation in 2D and 3D environments through regulation of fibronectin domain stability. Biomaterials. 2009;30:1089–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bershadsky AD, Balaban NQ, Geiger B. Adhesion-dependent cell mechanosensitivity. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:677–695. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111301.153011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choquet D, Felsenfeld DP, Sheetz MP. Extracellular matrix rigidity causes strengthening of integrin-cytoskeleton linkages. Cell. 1997;88:39–48. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81856-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giovannini M, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound elastography: the first step towards virtual biopsy? Preliminary results in 49 patients. Endoscopy. 2006;38:344–348. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-925158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahadevan D, Von Hoff DD. Tumor-stroma interactions in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1186–1197. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walker RA. The complexities of breast cancer desmoplasia. Breast cancer research : BCR. 2001;3:143–145. doi: 10.1186/bcr287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brownstein MH, Shapiro L. Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma. Cancer. 1977;40:2979–2986. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197712)40:6<2979::aid-cncr2820400633>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valensi QJ. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma: study of a case by light and electron microscopy. The Journal of dermatologic surgery and oncology. 1979;5:31–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1979.tb00600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eversole LR, Leider AS, Hansen LS. Ameloblastomas with pronounced desmoplasia. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 1984;42:735–740. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(84)90423-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caporale A, et al. Is desmoplasia a protective factor for survival in patients with colorectal carcinoma? Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2005;3:370–375. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00674-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mueller MM, Fusenig NE. Friends or foes - bipolar effects of the tumour stroma in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:839–849. doi: 10.1038/nrc1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akiri G, et al. Lysyl oxidase-related protein-1 promotes tumor fibrosis and tumor progression in vivo. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1657–1666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Colpaert C, Vermeulen P, Van Marck E, Dirix L. The presence of a fibrotic focus is an independent predictor of early metastasis in lymph node-negative breast cancer patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1557–1558. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200112000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Colpaert C, et al. Intratumoral hypoxia resulting in the presence of a fibrotic focus is an independent predictor of early distant relapse in lymph node-negative breast cancer patients. Histopathology. 2001;39:416–425. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2001.01238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guo W, Giancotti FG. Integrin signalling during tumour progression. Nature reviews. 2004;5:816–826. doi: 10.1038/nrm1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Desgrosellier JS, Cheresh DA. Integrins in cancer: biological implications and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Runnels JM, Chen N, Ortel B, Kato D, Hasan T. BPD-MA-mediated photosensitization in vitro and in vivo: cellular adhesion and beta1 integrin expression in ovarian cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 1999;80:946–953. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Casey RC, et al. Beta 1-integrins regulate the formation and adhesion of ovarian carcinoma multicellular spheroids. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:2071–2080. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63058-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park CC, et al. Beta1 integrin inhibitory antibody induces apoptosis of breast cancer cells, inhibits growth, and distinguishes malignant from normal phenotype in three dimensional cultures and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1526–1535. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sawada K, et al. Loss of E-cadherin promotes ovarian cancer metastasis via alpha 5-integrin, which is a therapeutic target. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2329–2339. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shield K, et al. Alpha2beta1 integrin affects metastatic potential of ovarian carcinoma spheroids by supporting disaggregation and proteolysis. J Carcinog. 2007;6:11. doi: 10.1186/1477-3163-6-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Celli JP, Solban N, Liang A, Pereira SP, Hasan T. Verteporfin-based photodynamic therapy overcomes gemcitabine insensitivity in a panel of pancreatic cancer cell lines. Lasers Surg Med. 2011;43:565–574. doi: 10.1002/lsm.21093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Uzdensky AB, et al. Photosensitization with protoporphyrin IX inhibits attachment of cancer cells to a substratum. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;322:452–457. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.07.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Volanti C, et al. Downregulation of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression in endothelial cells treated by photodynamic therapy. Oncogene. 2004;23:8649–8658. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jiang F, et al. Photodynamic therapy with photofrin reduces invasiveness of malignant human glioma cells. Lasers Med Sci. 2002;17:280–288. doi: 10.1007/s101030200041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vonarx V, et al. Photodynamic therapy decreases cancer colonic cell adhesiveness and metastatic potential. Res Exp Med (Berl) 1995;195:101–116. doi: 10.1007/BF02576780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kwabi-Addo B, Ozen M, Ittmann M. The role of fibroblast growth factors and their receptors in prostate cancer. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2004;11:709–724. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cheng JD, et al. Promotion of tumor growth by murine fibroblast activation protein, a serine protease, in an animal model. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4767–4772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hwang RF, et al. Cancer-Associated Stromal Fibroblasts Promote Pancreatic Tumor Progression. Cancer research. 2008;68:918–926. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martin M, Pujuguet P, Martin F. Role of Stromal Myofibroblasts Infiltrating Colon Cancer in Tumor Invasion. Pathology - Research and Practice. 1996;192:712–717. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(96)80093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ohuchida K, et al. Radiation to stromal fibroblasts increases invasiveness of pancreatic cancer cells through tumor-stromal interactions. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3215–3222. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bardeesy N, DePinho R. Pancreatic cancer biology and genetics. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2002;2:897–909. doi: 10.1038/nrc949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ulrich TA, Jain A, Tanner K, MacKay JL, Kumar S. Probing cellular mechanobiology in three-dimensional culture with collagen-agarose matrices. Biomaterials. 2010;31:1875–1884. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Celli JP, Rizvi I, Evans CL, Abu-Yousif AO, Hasan T. Quantitative imaging reveals heterogeneous growth dynamics and treatment-dependent residual tumor distributions in a three-dimensional ovarian cancer model. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2010;15:051603–051610. doi: 10.1117/1.3483903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rizvi I, et al. Synergistic Enhancement of Carboplatin Efficacy with Photodynamic Therapy in a Three-Dimensional Model for Micrometastatic Ovarian Cancer. Cancer research. 2010;70:9319–9328. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aveline B, Hasan T, Redmond RW. Photophysical and photosensitizing properties of benzoporphyrin derivative monoacid ring A (BPD-MA) Photochem Photobiol. 1994;59:328–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1994.tb05042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rahmanzadeh R, et al. Ki-67 as a Molecular Target for Therapy in an In vitro Three-Dimensional Model for Ovarian Cancer. Cancer research. 2010;70:9234–9242. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lo PC, et al. Photodynamic molecular beacon triggered by fibroblast activation protein on cancer-associated fibroblasts for diagnosis and treatment of epithelial cancers. J Med Chem. 2009;52:358–368. doi: 10.1021/jm801052f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sandanayake NS, et al. Optical Methods for Tumor Treatment and Detection: Mechanisms and Techniques in Photodynamic Therapy XIX. Vol. 7551. SPIE; San Francisco, California, USA: 2010. PDT for locally advanced pancreatic cancer: early clinical results; pp. 75510L–75518. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Duska LR, Hamblin MR, Miller JL, Hasan T. Combination photoimmunotherapy and cisplatin: effects on human ovarian cancer ex vivo. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1557–1563. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.18.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.del Carmen MG, et al. Synergism of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-Targeted Immunotherapy With Photodynamic Treatment of Ovarian Cancer In Vivo. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2005;97:1516–1524. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]