Abstract

To assess differences in psychosocial wellbeing between recent orphans and non-orphans, we followed a cohort of 157 school-going orphans and 480 non-orphans ages 9-15 in a context of high HIV/AIDS mortality in South Africa from 2004 to 2007. Several findings were contrary to published evidence to date, as we found no difference between orphans and non-orphans in anxiety/depression symptoms, oppositional behavior, self-esteem, or resilience. Female gender, self-reported poor health, and food insecurity were the most important predictors of children’s psychosocial wellbeing. Notably, girls had greater odds of reporting anxiety/depression symptoms than boys, and scored lower on self-esteem and resilience scales. Food insecurity predicted greater anxiety/depression symptoms and lower resilience. Perceived social support was a protective factor, as it was associated with lower odds of anxiety/depression symptoms, lower oppositional scores, and greater self-esteem and resilience. Our findings suggest a need to identify and strengthen psychosocial supports for girls, and for all children in contexts of AIDS-affected and economic adversity.

Introduction

South Africa continues to experience a particularly dramatic orphan crisis due in large part to the country’s expanding HIV/AIDS epidemic. Of the 3.7 million orphans (an estimated 20 percent of the child population) in 2007, one-half were orphaned due to AIDS (Statistics South Africa, 2008). Even with scaled-up treatment rollouts, the number of orphans is expected to grow through at least 2015 (Actuarial Society of South Africa, 2005). Developing a rigorous evidence base to understand how the death of a parent affects the mental health of children is critical to developing effective policies and programs to care for, educate, and socialize children, while maximizing resources. Although the evidence characterizing the psychosocial experience of children orphaned by AIDS is improving, much remains to be understood.

Prior to 2007, relatively little research on the psychological effects of HIV-related orphanhood in sub-Saharan Africa had been published. Since that time, a number of studies have reported on the psychosocial impacts to orphans in Ghana (Doku, 2009), Guinea (Delva et al., 2009), Namibia (Ruiz-Casares, Thombs, & Rousseau, 2009), Rwanda (Thurman, Snider, Boris, Kalisa, Mugarira, et al., 2006), South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zimbabwe (Wood, Chase, & Aggleton, 2006). For example, in a South African study, AIDS orphans had higher levels of depression, peer problems, PTSD, and conduct problems than other orphans (Cluver, Fincham, & Seedat, 2009). In a national survey of 5321 children in Zimbabwe, maternal, paternal and double orphans (both male and female) all had higher levels of psychosocial distress (a composite of the Child Behavior Checklist, the Rand Mental Health Inventory, and Beck’s Depression Inventory) than non-orphans (Nyamukapa et al., 2008). In this body of literature, orphans generally exhibit more psychosocial problems than non-orphans, with greater difficulties for AIDS orphans than for orphans due to other causes (Atwine, Cantor-Graae, & Bajunirwe, 2005; Makame, Ani, & Grantham-McGregor, 2002; Nyamukapa et al., 2008).

A few of these studies also report associations between psychological outcomes (internalization disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, delinquency, etc.) and a number of mediating factors, including gender, poverty, nutritional status, stigma, being bullied, and community support or marginalization. For instance, Cluver and colleagues report findings from a large cohort of adolescents in Cape Town showing that AIDS orphans were more likely to experience psychological distress compared to children orphaned by other causes or non-orphans. Psychological distress in adolescent AIDS orphans, however, was contingent upon social and family contexts (Cluver, Gardner, & Operario, 2008; Cluver & Orkin, 2009; Cluver et al., 2009). Likewise, 83% of AIDS orphans who reported experiencing stigma and hunger were diagnosed with an internalizing disorder compared to 19% who reported neither (Cluver & Orkin, 2009). After a four-year time period, AIDS orphans in the cohort reported increased depression, anxiety, and PTSD compared to other-cause orphans and non-orphans (Cluver, Orkin, Gardner, & Boyes, 2011). With the exception of this Cape Town cohort (Cluver et al., 2011) and two randomized controlled trials assessing the impact of psychosocial interventions (Kumakech, Cantor-Graae, Maling, & Bajunirwe, 2009; Ssewamala, Han, & Neilands, 2009), the published data are cross-sectional or qualitative. While many articles explore the dynamics of orphan, socioeconomic, and nutritional status and child mental health, the cross-sectional data cannot provide information with which to delineate determinants of vulnerability and resilience over time.

To improve understanding of how the recent death of a parent affects the psychosocial well-being of school-aged children and changes over time, we recruited and followed a cohort of recent orphans and non-orphans in Amajuba District of KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), South Africa between 2004 and 2007. In the context of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in southern Africa, the vulnerability of orphans and other affected children is linked to multiple forms of adversity, including poverty and food insecurity which are exacerbated by HIV-related illness and death (Drimie & Casale, 2009). This “entangled crisis” affects individuals, households, and communities (Drimie & Casale, 2009). A vulnerable child’s resilience, or positive adaptation to such adversity, is often described as being linked to protective factors such as education, family bonds, social support within the larger community, and material assistance (Luthar, 1991; Petersen et al., 2010; Pinkerton & Dolan, 2007).

In this paper, we report longitudinal findings on the psychosocial wellbeing (depression-anxiety/internalizing problems; connectedness and social support; resilience; self-esteem) of recent orphans compared to non-orphans in this cohort of school-attending adolescents. The specific aims of this paper are 1) to assess whether orphan status is the primary determinant of psychosocial wellbeing in the first years after recent orphaning, and 2) to examine the psychosocial stressors and protective factors promoting resilience in children living in a context of generalized poverty and high HIV prevalence. In keeping with other research on the vulnerabilities and protective factors influencing the wellbeing of children orphaned by HIV, we hypothesized that orphans would have poorer outcomes across multiple domains compared to non-orphans, with outcomes worsening longitudinally. We expected that poor health and food insecurity would also be associated with poorer outcomes. We also hypothesized that we would find an inverse relationship between perceived social support and connectedness and psychosocial problems, whereby perceiving strong social support and feeling connected to peers, family, and community would be protective against behavioral and emotional problems.

Methods

Study site and population

The study population comprised school-going isiZulu-speaking children aged 9 to15 years residing in Amajuba District of KZN. Children were excluded if they did not speak isiZulu or English, had a severe disability, or were not attending school at time of study enrollment.

Sampling and data collection procedures

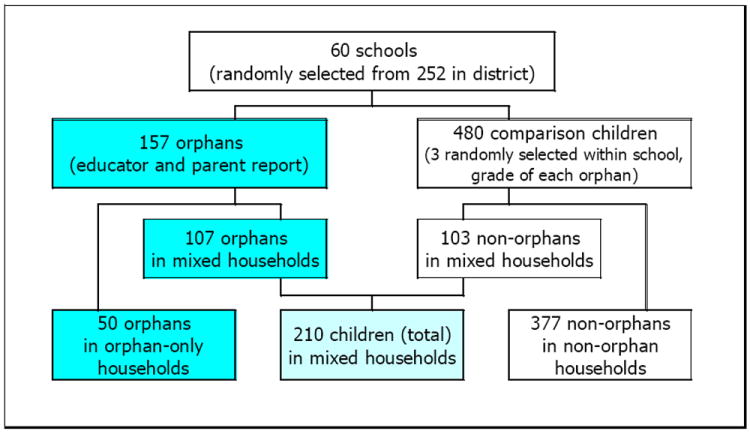

The starting sample included 637 children 9 to 15 years old, divided into 157 incident orphans and 480 non-orphans. The sample selection process used school- and age-based stratified cluster sampling from 252 primary and secondary schools in Amajuba District. Figure 1 portrays the selection process and distribution of children by household type. At each randomly-selected school, teachers completed an ‘incident’ orphan identification form for children in their classrooms. Incident orphans were defined as children who had experienced a parent’s death due to any cause within a four month period between March and August 2004. Comparison non-orphans were selected if they reported both their mother and father alive. For each incident orphan, three comparison (non-orphan) children were selected via a random-number procedure from the same school, grade, and age group to assure sufficient size of the comparison group considering high rates of ongoing orphaning indicated by earlier district data (Badcock-Walters, Heard, & Wilson, 2002). At the first household visit, research interviewers confirmed with the primary caregiver the child’s orphan vs. non-orphan status. Informed consent and assent processes were conducted in isiZulu with adult and child respondents after households of identified children provided permission for participation. The Boston University Medical Center Institutional Review Board and the University of KwaZulu-Natal Ethics Committee provided ethical approval.

Figure 1. Sample selection process.

Between September 2004 and June 2005, 637 children were interviewed by trained research assistants and asked questions related to their psychosocial wellbeing, in addition to other questions. The head of each household and the primary caregiver of each study child were also interviewed by research assistants and asked questions related to socioeconomic status and household membership, in addition to other questions. The surveys were repeated twice at annual intervals. In Round 2 (2006), 598 children were re-interviewed; in Round 3 (2007), 568 children were re-interviewed, an overall retention rate of 89.2%.

Outcome measures: Anxiety/depression, oppositional, self-esteem, resilience, worries

We modified validated instruments which had previously been used in a population of isiZulu-speaking children in KZN (Killian & Spencer, 2004). Trained research assistants pre-tested the original isiZulu translated surveys in cognitive interviews with 9-15 year-olds in Amajuba District to assess respondent burden and comprehension of items (Tourangeau, 1984). Our modifications exclusively involved abbreviating the instruments based on local researchers’ concerns about burdening respondents with an already long survey and human subjects concerns requiring adequate referral processes if clinically depressed or suicidal children were identified. The questions are itemized in Appendix 1. For all measures except for worries, each question included four response options (always, often, sometimes, never the case).

Depression/Anxiety and Worries

Items for our 21-item anxiety/depression subscale were taken from the Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale (RADS-2) (Reynolds, 2002). We collapsed the responses due to a skewed distribution: for anxiety/depression, “always and often” were equal to 1, and other responses equal to 0. The internal reliability for this subscale was good (Cronbach’s α=0.80). Because the anxiety/depression subscale was highly skewed towards no symptoms, we used cut-off values to meet normality requirements, with those in the top quintile coded as “1” for anxiety/depression, and those with fewer symptoms “0”. Beginning in Round 2, we asked respondents how worried they were about their health, having enough food and money, pregnancy, and HIV/AIDS, adapted from Kloep (Kloep, 1999). Responses of “very worried”, “somewhat worried”, “not worried”, or “don’t know” were recoded into a dichotomous variable, with “very worried” coded as “1” and other responses as “0”.

Self-esteem and Resilience

The 11-item self-esteem subscale came from the adolescent Culture Free Self-esteem Inventory (CFSEI) (Battle, 1992), and the 7-item resilience subscale from the Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children (TSCC) (Briere, 1996). For both of these scales, we categorized “always” as equal to 1 and other responses equal to 0 due to skewed distributions. The internal reliability coefficients for these subscales were acceptable (α=0.79 for self-esteem and α=0.80 for resilience).

Oppositional behavior

The 10-item oppositional subscale was derived from the Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children (TSCC) (Briere, 1996). “Always” and “often” responses were collapsed and set equal to 1 and other responses equal to 0 due to a skewed distribution. Although the internal reliability of this subscale was relatively low (α=0.63), we used it under the rationale that scales with lower internal consistency can still be valid, as component questions may measure dissimilar aspects of a phenomenon (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001).

Other measures

Household measures

Questions for child- and household-level demographic and socioeconomic variables were derived from the South African 2001 Census, South Africa Integrated Household Survey (World Bank 1999), UNICEF Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey, and South African Survey of Time Use (Statistics South Africa 2001). Indicator variables were constructed for household type (orphan-only, non-orphan-only, mixed) and considered for inclusion in models.

Health status & food security measures

Two measures of self-reported health status (very ill in past 12 months; health currently worse than one year ago) were administered, as well as two adapted household-reported measures of food insecurity (days in previous month and months in previous year without enough food) (Coates, Webb, & Houser, 2003). These measures were used beginning in Round 2 as proxy measures for poverty, in addition to one child-reported measure (“In your life until now, how often did your family not have enough food to feed everyone?”) (Connell, Nord, Lofton, & Yadrick, 2004).

Social Support

For social support, we adapted a five-item measure to assess perceived social support received from family, friends, and significant others (Zimet et al., 1988). These yes/no questions (1=yes, 0=no) were summed into a social support scale. To measure connectedness across family, peer, and community domains, we developed a checklist to determine whether important adults (teacher, parent, etc.) were actively involved in the child’s life.

Statistical analysis

The analysis includes the 157 orphans and 480 non-orphans interviewed at baseline (total N=637). Two orphans did not complete the baseline psychosocial interview and were excluded from that round. Those lost to attrition (N=70) and non-orphans who became orphans (N=52) are included in the analysis for rounds before they exited the study or changed status. The analytic sample for the longitudinal analysis included 1722 observations, up to three per child.

The primary predictor variable was orphan status (orphan/non-orphan). Baseline cross-sectional relationships between orphan status, demographic and socioeconomic characteristics and psychosocial measures were assessed using Mantel-Haenszel chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. For the longitudinal analysis, we used generalized estimating equations (GEE) for binary outcomes and general linear mixed models for continuous outcomes to test associations between orphan status and child well-being over the three years of the study (Liang & Zeger, 1986). Both types of models not only account for the correlations between observations (within subjects), essential for longitudinal studies, but also permit inclusion of subjects with missing data (Liang & Zeger, 1986; Verbeke & Molenberghs, 2000). Children with missing data at Round 2 or 3 were included in the analyses, reducing bias that might have resulted from differential loss of less “healthy” children.

To identify candidate variables for multivariate models, demographic and socioeconomic characteristics expected to be potential confounders were tested for their bivariate associations with psychosocial outcomes using GEE. Models were then constructed with each subscale as the outcome, orphan status as the primary predictor, and other covariates significant in bivariate analysis (at the p<0.20 level) using a manual backward stepwise selection procedure. Child’s age, gender, and orphan status were included in all models. Health status, food security, and social support were added to each model to test for effect modifications. Health status and food security were considered as possible modifying factors because of the potential association between health and nutrition and psychological wellbeing (Mechanic & Hansell, 1987). Likewise, poverty has been found by some to be negatively associated with psychological well-being (Cluver & Orkin, 2009; Galea et al., 2007; Laraia, Siega-Riz, Gundersen, & Dole, 2006). Social support has been found to positively affect mental health (Schenk, 2009). Interactions between orphan status and time, orphan status and gender, and gender and social support were tested for each outcome; p<0.05 indicated that an interaction was present. For all GEE models, results from independent, autoregressive, and unstructured correlation structures were compared; results did not differ substantially, so we used an unstructured correlation structure for all models presented. Results for binary outcomes are expressed as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Results for continuous outcomes are expressed as means with standard deviations (SD). Data were analyzed using SAS software version 9.1 (The SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A probability of p=0.05 defined statistical significance.

Results

Cross-sectional findings

Table 1 presents baseline demographics of the study participants. The primary differences between the orphans and non-orphans related to caregivers and living situation, with orphans more likely to have a grandparent as a caregiver, and to report a household member who drinks and makes problems. Orphans were more likely to report being very ill in the past year (32% vs. 24%, p=0.0393), but only marginally more likely to report worse health status than in the previous year compared to non-orphans (12% vs. 8%, p=0.0613). We found no other demographic or economic differences (including food insecurity) between orphans and non-orphans and their households.

Table 1.

Characteristics of orphans and non-orphans at baseline (2004-2005)

| Orphans (N=157) | Orphans (N=480) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Characteristic | No. (%) | Mean (SD) | No. (%) | Mean (SD) | p1 |

| Basic characteristics | |||||

| Gender (% female) | 75 (48.1) | 227 (47.2) | 0.8478 | ||

| Age (years) | 12.5 (1.9) | 12.4 (2.0) | 0.6624 | ||

| Orphan type (for orphans only) | - | ||||

| Maternal | 54 (34.4) | ||||

| Paternal | 60 (38.2) | ||||

| Double | 43 (27.4) | ||||

| Household characteristics | |||||

| Household size | 7.4 (3.0) | 7.3 (3.2) | 0.6781 | ||

| Chronically ill adult resident | 109 (69.9) | 337 (70.1) | 0.9640 | ||

| Death of member in previous 12 months | 154 (98.7) | 75 (15.6) | <0.0001 | ||

| At least one adult employed | 87 (55.8) | 303 (63.0) | 0.1078 | ||

| Asset index | 4.3 (1.8) | 4.4 (2.0) | 0.7652 | ||

| Living arrangements and mobility | |||||

| Have never changed residence | 114 (73.1) | 331 (69.5) | 0.4010 | ||

| Caregiver type | |||||

| Parent | 39 (25.8) | 311 (65.2) | <0.0001 | ||

| Grandparent | 81 (53.6) | 104 (21.8) | |||

| Another person | 31 (20.5) | 62 (13.0) | |||

| Household member drinks, makes problems2 | 34 (23.0) | 59 (14.3) | 0.0154 | ||

| Household type | |||||

| Non-orphan only | - | 377 (73.4) | <0.0001 | ||

| Orphan only | 50 (32.1) | - | |||

| Mixed | 106 (67.9) | 104 (21.6) | |||

| Self reported health status (% yes) | |||||

| Worse health status compared to one year ago | 19 (12.4) | 36 (7.5) | 0.0613 | ||

| Very ill in past 12 months | 50 (32.3) | 115 (23.9) | 0.0393 | ||

| Food insecurity (% yes)2 | |||||

| Family does not have enough food very often (child report) | 15 (10.2) | 28 (6.8) | 0.1835 | ||

| Food insecure in previous month (> 10 days without adequate food) | 34 (22.5) | 71 (17.0) | 0.1303 | ||

| Food insecure in previous 12 months (> 5 months without adequate food) | 33 (22.0) | 78 (18.6) | 0.3698 | ||

P-values from chi-square tests for categorical variables, from t-tests for continuous variables

Household drinking and food insecurity questions added in Round 2.

Cross-sectional associations between orphan status and psychosocial outcomes, and moderating factors at baseline are presented in Table 2. We noted relatively low anxiety/depression symptoms among all children, with no difference between orphans and non-orphans. Similarly, we found no difference in oppositional symptoms, self-esteem, or resilience. A few individual questions did indicate differences. See Appendix 1. For anxiety/depression symptoms, a larger proportion of orphans than non-orphans felt like crying, sad, no good, and sorry for themselves, but a larger proportion of non-orphans reported feeling that other kids did not like them. For self-esteem, a larger proportion of orphans reported wanting to talk to other children and enjoying helping others.

Table 2.

Psychosocial profile and potentially mediating factors of orphans and non-orphans at baseline

| Orphans (N=155) | Non-Orphans (N=480) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Domain | No. (%) | Mean (SD) | No. (%) | Mean (SD) | p1 |

| Psychosocial subscales2,3 | |||||

| Anxiety/Depression (21 items) | 4.54 (3.96) | 4.22 (3.66) | 0.3543 | ||

| Top quintile | 34 (21.9) | 94 (19.6) | 0.5260 | ||

| Oppositional (10 items, Round 2) | 1.60 (1.72) | 1.51 (1.68) | 0.5953 | ||

| Self esteem (11 items, Round 2) | 5.93 (2.89) | 5.94 (3.16) | 0.9734 | ||

| Resilience (7 items, Round 2) | 4.07 (2.22) | 4.08 (2.26) | 0.9571 | ||

| Worries (% responding “very worried”) | |||||

| Your health? | 35 (23.3) | 91 (21.6) | 0.6633 | ||

| Getting enough to eat? | 28 (18.7) | 70 (16.6) | 0.5698 | ||

| Getting money? | 40 (26.7) | 94 (22.3) | 0.2820 | ||

| Getting pregnant or getting someone pregnant? | 40 (26.7) | 144 (34.3) | 0.0870 | ||

| Getting HIV/AIDS? | 90 (60.0) | 237 (56.4) | 0.4481 | ||

| Social support (summated scale)) | 4.23 (1.05) | 4.40 (0.90) | 0.0654 | ||

| Individual questions; (% yes) | |||||

| Talks to parent/caregiver about feelings when upset | 128 (83.7) | 433 (90.4) | 0.0217 | ||

| Feels loved by parent/caregiver. | 143 (94.1) | 472 (98.5) | 0.0023 | ||

| Has a special person who is a source of comfort. | 130 (84.4) | 430 (89.6) | 0.0825 | ||

| Has friends to share joys and sorrows with. | 125 (81.2) | 399 (83.1) | 0.5773 | ||

| Friends give her/him encouragement. | 125 (81.2) | 382 (79.6) | 0.6691 | ||

P-values from chi-square tests for categorical variables, from t-tests for continuous variables

Baseline for anxiety/depression at Round 1: N=635, as 2 orphans did not complete questionnaire.

Baseline for other measures at Round 2: N= 572.

For individual social support questions at baseline, orphans were less likely to report talking to their living parent or caregiver (83.7% vs. 90.4%, p=0.0217) or feeling loved by a parent or caregiver (94.1% vs. 98.5%, p=0.0023). No significant differences were found for overall social support score or having a special person as a source of comfort, or in the proportions of orphans and non-orphans either reporting having friends to share joys and sorrows with or reporting that friends “give them encouragement”.

Table 3 presents baseline results of social connectedness. No significant differences are noted between orphans and non-orphans with regards to important people in their life, who they can talk to about problems, or turn to for money or things they need. The only significant association was that orphans were more likely to talk to a grandmother about their problems than non-orphans.

Table 3.

Persons involved in lives of orphans and non-orphans at baseline (2004-2005)

| Involved in life | Talks about problems2 | Helps with money, things2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Orphans (N=155) | Non-Orphans (N=480)1 | Orphans | Non-orphans | Orphans | Non-orphans | |

|

| ||||||

| Person | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) |

| a. A teacher (N=634)3 | 142 (92.2) | 437 (91.0) 0.6549 | 91 (63.2) | 255 (58.4) 0.3050 | 58 (40.3) | 197 (45.0) 0.3245 |

| b. A parent (N=597) | 115 (97.5) | 476 (99.4) 0.0618 | 105 (91.3) | 444 (93.3) 0.4603 | 108 (93.9) | 471 (99.0) 0.0006 |

| c. A grandmother (N=506) | 121 (96.0) | 364 (95.8) 0.9060 | 107 (88.4) | 277 (76.1) 0.0038 | 107 (89.9) | 326 (89.3) 0.8531 |

| d. A grandfather (N=335) | 65 (85.5) | 190 (84.8) 0.8820 | 39 (59.1) | 108 (57.1) 0.7832 | 56 (86.2) | 146 (77.3) 0.1256 |

| e. An older sister or brother (N=505) | 102 (92.7) | 382 (96.7) 0.0646 | 76 (75.3) | 286 (75.1) 0.9700 | 77 (75.5) | 317 (83.0) 0.0843 |

| f. An aunt or uncle (N=584) | 129 (89.6) | 400 (90.9) 0.6367 | 84 (66.7) | 241 (60.4) 0.2072 | 102 (79.7) | 309 (77.3) 0.5637 |

| g. A friend (N=617) | 138 (93.9) | 443 (94.3) 0.8647 | 121 (87.7) | 364 (81.8) 0.1067 | 109 (79.6) | 350 (78.8) 0.8540 |

| h. A boyfriend or girlfriend (N=170) | 29 (64.4) | 66 (52.8) 0.1786 | 21 (72.4) | 53 (75.7) 0.7322 | 18 (62.1) | 49 (71.0) 0.3872 |

| i. A pastor/ religious leader (N=499) | 86 (69.1) | 263 (70.0) 0.8602 | 35 (41.7) | 97 (36.9)0.4323 | 27 (32.5) | 85 (32.2) 0.9549 |

| j. A youth leader (N=343) | 40 (46.0) | 133 (52.0) 0.3362 | 18 (43.9) | 63 (46.3) 0.7856 | 19 (46.3) | 61 (44.9) 0.8671 |

| k. Other adult in the community (N=299) | 49 (58.3) | 135 (62.8) 0.4772 | 39 (79.6) | 95 (70.4) 0.2152 | 43 (87.8) | 112 (83.0) 0.4316 |

P-values from chi-square tests.

“Always” or “sometimes” vs. “Never”

N’s are for “involved” question; fewer responses to subsequent person-specific questions

Longitudinal findings

Table 4 presents results from the longitudinal analysis of psychosocial subscales. Overall, we found no statistical differences between orphans and non-orphans in any of the psychosocial scales.

Table 4.

Longitudinal models of psychosocial outcomes

| Anxiety/Depression Rounds 1-3 |

Anxiety/Depression Rounds 2-3 |

Oppositional Rounds 2-3 |

Self esteem Rounds 2-3 |

Resilience Rounds 2-3 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Variable1 | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p | Adjusted effect estimate (SE) | p | Adjusted effect estimate (SE) | p | Adjusted effect estimate (SE) | p |

| Intercept | 1.14 (0.49) | 8.54 (0.93) | 4.73 (0.65) | |||||||

| Basic characteristics | ||||||||||

| Orphan | 1.13 (0.82-1.56) | 0.4585 | 1.10 (0.77-1.58) | 0.6033 | 0.43 (0.18) | 0.0170 | 0.14 (0.29) | 0.6278 | -0.14 (0.17) | 0.4119 |

| Gender (female) | 2.22 (1.68-2.92) | <0.0001 | 1.87 (1.36-2.56) | 0.0001 | 0.62 (0.14) | <0.0001 | -1.06 (0.21) | <0.0001 | -0.78 (0.15) | <0.0001 |

| Age (years) | 1.02 (0.96-1.10) | 0.4972 | 1.00 (0.92-1.08) | 0.9357 | 0.02 (0.03) | 0.5199 | -0.22 (0.05) | <0.0001 | -0.06 (0.04) | 0.1010 |

| Household characteristics | ||||||||||

| Number of children in household | 1.08 (1.02-1.15) | 0.0093 | 1.09 (1.02-1.17) | 0.0122 | ||||||

| Public grant accessed | 0.42 (0.13) | 0.0018 | ||||||||

| Child grant accessed | -0.38 (0.15) | 0.0109 | ||||||||

| Asset index | 0.88 (0.82-0.94) | 0.0003 | 0.91 (0.83-0.99) | 0.0414 | ||||||

| Household member drinks, makes problems for others | 1.73 (1.21-2.49) | 0.0030 | ||||||||

| Interview round (1,2, or 3) | ||||||||||

| Round 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Round 2 | 1.65 (1.31-2.09) | <0.0001 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Round 3 | 1.22 (0.93-1.60) | 0.1587 | 0.75 (0.57-0.98) | 0.0343 | -0.16 (0.08) | 0.0550 | 0.61 (0.18) | 0.0010 | 0.33 (0.11) | 0.0040 |

| Health status (self-report) | ||||||||||

| Health worse than year ago | 0.59 (0.19) | 0.0016 | -1.29 (0.35) | 0.0002 | -0.79 (0.25) | 0.0016 | ||||

| Very ill in last 12 months | 1.51 (1.16-1.97) | 0.0022 | 1.61 (1.11-2.33) | 0.0113 | -0.46 (0.25) | 0.0655 | ||||

| Food insecurity | ||||||||||

| Child report | -0.48 (0.23) | 0.0398 | ||||||||

| Household report | 1.46 (1.00-2.14) | 0.0499 | ||||||||

| Social support | 0.82 (0.71-0.94) | 0.0035 | 0.84 (0.71-0.99) | 0.0444 | -0.13 (0.06) | 0.0337 | 0.39 (0.11) | 0.0003 | 0.19 (0.08) | 0.0159 |

| Interaction terms | ||||||||||

| Gender*orphan status | -0.57 (0.26) | 0.0294 | ||||||||

| Orphan status*time | -0.76 (0.36) | 0.0377 | ||||||||

Only those covariates that appear in final models are presented here.

Anxiety/depression symptoms

We found no difference between orphans and non-orphans in anxiety/depression symptoms in bivariate or multivariate analysis. In the model that included all three survey rounds, girls were more than twice as likely to report anxiety/depression symptoms compared to boys (OR=2.22, 95% CI=1.68-2.92). Other factors associated with greater odds of anxiety/depression included more children in the household (OR=1.08, 95% CI=1.02-1.15), and the respondent being very ill in the past year (OR=1.51, 95% CI=1.16-1.97). A higher household asset index was associated with lower odds of depressive symptoms (OR=0.88, 95% CI=0.82-0.94). Respondents were more likely to report depressive symptoms in Round 2 compared to Round 1 (OR=1.65, 95% CI=1.31-2.09); there was no significant difference between Round 3 and Round 1. Higher social support was associated with significantly lower odds of depressive symptoms (OR=0.82, 95% CI=0.71-0.94).

In the model that included only Rounds 2 and 3, the same predictors were significantly associated with anxiety/depression symptoms with similar magnitudes. Household food insecurity emerged as an important predictor of anxiety/depression symptoms (OR 1.46, 95% CI=1.00-2.14). In addition, reporting that a household member drinks and makes problems (added in Round 2) was associated with 73% greater odds of anxiety/depression symptoms (OR=1.73, 95% CI=1.21-2.49).

Oppositional behavior

In multivariate analysis, female gender, receipt of a public grant, and worse health than the year prior were associated with higher oppositional scores. Social support was associated with lower opposition. We found a significant interaction between gender and non-orphan status in this model, with the effect of gender varying by orphan status.1 Among non-orphans, girls had higher oppositional scores than boys (stratified results not shown); no gender differences were evident among orphans. On average, oppositional scores were lower in Round 3 than in Round 2.

Self-esteem

For self-esteem, significant multivariate predictors over the second and third rounds of the study included gender, age, worse health, being very sick in the past year, and time (round). Girls scored much lower than did boys on self-esteem (p<0.0001). For both genders, older age was associated with lower self-esteem (p<0.0001). Respondent reports of worse health than one year previously and being very ill in the past 12 months were independently associated with lower scores (p=0.0002 and p=0.0655). Greater social support also predicted higher self-esteem (p=0.0003). There was a significant interaction between orphan status and time, with orphans scoring significantly lower in self-esteem compared to non-orphans in Round 3 (but not in Round 2) (p for interaction=0.0377).

Resilience

Significant predictors of resilience over Rounds 2 and 3 included gender, household receipt of a child grant, health status compared to a year ago, household food security, social support, and interview round. Again, there was no difference in resilience by orphan status. Girls appeared to be less resilient than boys (p<0.0001). Reporting worse health than a year ago was associated with a lower score (p=0.0020), as was receipt of a child grant (p=0.0109). Child-reported food insecurity was also associated with lower resilience (p=0.0398). Finally, social support significantly predicted resilience, with greater social support associated with higher resilience (p=0.0159). On average, respondents had lower resilience scores in Round 3 than in Round 2 (p=0.0040).

Worries

Table 5 presents results from multivariate longitudinal analysis of respondents’ worries. Orphans and non-orphans did not exhibit differences in worries about important life issues. Poor self-reported health and food insecurity were the strongest predictors of health, food, and money worries, with poor health and greater food insecurity associated with greater worry about these issues. Gender was an important predictor of all worries except getting enough to eat, with girls being more likely to report being worried about money, pregnancy, and HIV/AIDS, but less likely to be worried about health (marginal significance). Greater social support had a protective association against worries about health and money, i.e., those with higher social support scores were less likely to report worrying about these issues. However, we found an inverse association between social support and pregnancy worries, i.e., those with higher social support scores were less likely to worry about pregnancy. On average, respondents were more likely to report worries in Round 3 compared to Round 2. Girls, older children, children in the poorest households, and those with an ill household member were more likely to worry about getting HIV/AIDS.

Table 5.

Longitudinal models of worries

| Variable1 | Health | Getting enough to eat | Getting money | Getting pregnant or getting someone pregnant | Getting HIV/AIDS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Basic characteristics | ||||||||||

| Orphan | 1.26 (0.89-1.78) | 0.1927 | 1.11 (0.77-1.60) | 0.5769 | 1.31 (0.94-1.84) | 0.1107 | 0.73 (0.53-1.02) | 0.0693 | 1.04 (0.75-1.43) | 0.8113 |

| Gender (female) | 0.74 (0.53-1.01) | 0.0606 | 1.09 (0.78-1.51) | 0.6128 | 1.32 (0.98-1.79) | 0.0703 | 3.15 (2.34-4.25) | <0.0001 | 1.66 (1.23-2.23) | 0.0009 |

| Age (years) | 1.23 (1.13-1.34) | <0.0001 | 1.05 (0.97-1.13) | 0.2571 | 1.12 (1.03-1.21) | 0.0076 | 1.21 (1.12-1.30) | <0.0001 | 1.26 (1.17-1.36) | <0.0001 |

| Household characteristics | ||||||||||

| HH head education> primary | 0.71 (0.51-0.99) | 0.0431 | ||||||||

| Household member ill | 1.30 (0.98-1.71) | 0.0683 | ||||||||

| Lowest income quartile | 0.70 (0.52-0.95) | 0.0222 | ||||||||

| Interview round (2 or 3) | ||||||||||

| Round 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Round 3 | 2.55 (1.99-3.26) | <0.0001 | 1.53 (1.15-2.03) | 0.0033 | 1.33 (1.02-1.73) | 0.0320 | 2.04 (1.56-2.66) | <0.0001 | 2.12 (1.63-2.74) | <0.0001 |

| Moderating factors | ||||||||||

| Health worse than year ago | 2.22 (1.34-3.67) | 0.0018 | 1.58 (0.97-2.57) | 0.0653 | 2.42 (1.52-3.86) | 0.0002 | ||||

| Food insecurity, child report | 2.27 (1.39-3.71) | 0.0010 | 1.83 (1.16-2.89) | 0.0094 | ||||||

| Social support | 0.86 (0.73-1.02) | 0.0793 | 0.87 (0.74-1.02) | 0.0900 | 1.22 (1.04-1.44) | 0.0138 | ||||

Only those covariates that appear in final models are presented here.

Discussion

To our knowledge, these cross-sectional and longitudinal findings are a unique contribution to the current evidence on psychosocial distress and resilience among vulnerable children, both orphans and non-orphans, in the most heavily HIV-affected province in South Africa. In this three-year study of psychosocial vulnerability, we found no significant differences between incident orphans and non-orphans in anxiety/depression symptoms, oppositional behavior, self-esteem, resilience, and worries. To date, the available cross-sectional evidence has tended to focus on orphan status as the primary determinant of psychological wellbeing. The overall portrait painted by these studies suggests that orphans generally report greater psychological and social distress than non-orphans and children orphaned by other causes (Cluver & Gardner, 2007), with some studies finding differences in psychological distress by orphan type (Cluver et al., 2009; Ruiz-Casares et al., 2009). In contrast, we did not find differences by orphan status for any outcomes. Several dynamics could explain this discrepancy. We were not able to distinguish between causes of orphaning in our study, so it is possible that our results may mask differences between AIDS orphans and those orphaned due to other causes. However, HIV prevalence for Amajuba District was estimated at 39.4 percent in 2007 (Department of Health, 2008), and mortality data suggests that 15-49 year olds experience the highest mortality rates with tuberculosis as the leading cause of death in the district and among Black Africans. Additionally, in our study, orphans were interviewed between three and nine months after a parent’s death and may have experienced a different trajectory of mental health problems in bereavement than prevalent orphans with longer time since the parental death. Evidence from other studies including a longitudinal investigation in South Africa suggests that attenuated orphanhood may produce more marked differences in psychological and social distress (Cluver et al., 2011; Kaggwa & Hindin, 2010).

Alternatively, family environment (including both psychosocial stressors and protective factors) and not orphanhood per se may explain psychosocial differences. Such factors could include both socioeconomic factors and social support. For example, we found greater vulnerability to anxiety and depression symptoms associated with being female, self-reported poor health, and food insecurity in both orphans and non-orphans. Likewise, among all study children, greater social support was associated with a lower likelihood of anxiety/depression symptoms and a lower oppositional score, as well as with higher self-esteem and greater resilience. More generally, we identified perceived social support, male gender, self-reported good health, and household socioeconomic factors (such as food security, fewer children in the household, and a higher household asset index) as protective factors for psychosocial wellbeing.

Resilience and social support

Research on resilience suggests that multiple protective factors may buffer children against adversity, including individual characteristics (e.g., temperament) and socio-contextual factors (e.g., supportive relations, community resources) (Bonanno & Mancini, 2008). Parental death disrupts a child’s world, but the family may adapt over time by developing new patterns of relationships, and children adapt by managing their grief and by developing belief systems to make sense of their new relationships (Schmiege, Khoo, Sandler, Ayers, & Wolchik, 2006). The lack of difference we found between orphans and non-orphans could be a function of compensating for emotional distress with positive psychological functioning (‘putting on a good face’), positive adaptation, or protective factors within the child or social environment (i.e., rallying family support for orphans) (Li et al., 2008). We found that, while self-esteem was not associated with depression/anxiety symptoms, higher resilience scores were linked with a lower likelihood of these symptoms.

Perceived social support from friends and relatives (Bonanno & Mancini, 2008; Stroebe, Schut, & Stroebe, 2007) and instrumental support, such as financial assistance or help with maintenance of household responsibilities (Li et al., 2008; Stroebe et al., 2007), are two types of support examined in the bereavement literature. Our findings suggest that quality social support mitigates anxiety/depression symptoms, oppositional behavior, and worry among orphans. Orphans also reported being able to talk to a caregiver to a significant degree compared to non-orphans. This may be a result of orphaning whereby orphans rely on caregivers more than previously or seek out greater social support after the death of a parent (Thurman, Snider, Boris, Kalisa, Nkunda, et al., 2006).

Gender

Our findings align with those of Cluver, Gardner and Operario showing that girls in their Cape Town cohort are more inclined to depression, in contrast to those of Kagwaa and Hindin who found boys to be more affected by depression in their large school-based Uganda cohort (Cluver, Gardner, & Operario, 2007; Kaggwa & Hindin, 2010). Girls in our sample, both orphans and non-orphans, had a distinctly greater likelihood of reporting anxiety/depression symptoms and had higher oppositional scores, and lower self-esteem and resilience. International research examining gender differences in internalizing and externalizing behaviors may provide insight into the gender differences observed in this study. Boys tend to act out their personal problems and therefore are more likely to show externalizing behaviors, while girls more often show internalizing symptomatology (Fergusson, Woodward, & Horwood, 2000). A possible explanation for this difference between females and same-aged males could be that females are usually further along in their development and therefore might present with more emotional and behavioral problems than do males (Cyranowski, Frank, Young, & Shear, 2000). Additionally, females have been found to be more likely to communicate their problems to others and engage in help-seeking behaviors; however, they are also more likely to ruminate about problems they encounter which can affect their wellbeing (Hankin & Abramson, 2001). This might also explain our finding that in Round 3, girls reported being more worried about money, pregnancy, and HIV/AIDS than boys. These worries about pregnancy and HIV are supported by self-reports of sexual behavior from Round 3. Although the analyses were limited by the small numbers of respondents reporting sexual experience, of the 23 girls reporting having ever had sex, 8 of 20 (40%) reported that they had gotten pregnant, whereas of the 42 boys who reported sexual activity, only one (4%; 1/28) reported having gotten a girl pregnant (data not shown). This relatively large proportion of sexually active girls reporting pregnancy (40%, a proportion much higher than the 2004-2008 KZN provincial rate of 6.2% (Panday, Makiwane, Ranchod, & Letsoala, 2009)) suggests that adolescent risk for becoming infected with HIV is high in our cohort. The girls’ worries appear to be warranted.

Physical and mental health link

We found strong associations between physical and mental health. Respondents who reported significant anxiety/depression symptoms were 57% more likely to report being very ill in the past year than those who did not report symptoms, and had 2.15 times the odds of reporting worse health than a year ago, independent of orphan status (data not shown). Orphans reported poorer physical health than non-orphans (e.g. very ill in past 12 months). A key question is whether mental health is perceived in this sample as somatic symptoms (i.e., physical symptoms such as headache or stomachache) and, therefore, less detectable by measures of emotional distress. In the literature, mood and anxiety disorders are collapsed into an overarching class of emotional disorders. Depression is reflected in high levels of negative affect and low levels of positive affect and physiological hyperarousal (Prenoveau et al., 2010); symptoms have been described as encompassing cognition, mood, behavior, somatic systems, and suicidal ideation (Montague, Enders, Dietz, Dixon, & Cavendish, 2008). The orphans in our sample may well have been experiencing distress that was simply not detected in our scales because it was manifested as perceived poor physical health. We have not identified other orphan literature that clarifies these dynamics.

Socioeconomic factors

Food insecurity was an important predictor of anxiety/depression symptoms, lower resilience, and most worries in the cohort. This finding is similar to those from a Cape Town sample where the psychological distress of AIDS orphans was mediated by their social and family context, including poverty (Cluver et al., 2007; Cluver & Orkin, 2009; Cluver et al., 2008). In the same sample, 83% of AIDS orphans who reported experiencing stigma and hunger were diagnosed with an internalizing disorder compared to 19% who reported neither (Cluver & Orkin, 2009). Other studies examining a cross-section of South African children report that children from households with the lowest level of material resources, contrary to expectations, are rated as less oppositional than children in households with moderate resources (Barbarin & Richter, 2001). It may be that, in Amajuba, food insecurity—and other economic factors—affect children and their psychosocial functioning more acutely than orphanhood.

Limitations

The study has several limitations. First, because our sample was school-based and not population-based, our study by definition excluded households of children not enrolled in school. Although this proportion is under 5 percent in KZN (Department of Basic Education, 2010), it is possible that our sample is somewhat biased, as there is evidence that orphanhood reduces the likelihood of children attending school (Monasch & Boerma, 2004). Identifying psychosocial needs of school-going adolescents, however, may assist Department of Education officials in targeting specific at-risk groups. Second, as noted above, we did not ask about the cause of parental death due to concerns about stigma, so we were not able to distinguish between orphans whose parent(s) had died due to HIV/AIDS and orphans from other causes, and therefore cannot establish differences by orphaning cause, a weakness shared by numerous other studies of orphanhood and wellbeing (Sherr et al., 2008). Third, both orphans and non-orphans came from a variety of household and caretaking contexts, signifying that households may or may not have currently been experiencing prime-age adult illness; thus the comparison households were not necessarily “pure” controls (i.e. non-AIDS-affected households), a challenge inherent to research in contexts of very high HIV prevalence. In rounds 2 and 3 of the study, interviewers ascertained adult illness in the household at each visit, and it was considered for inclusion in statistical models. Finally, to the degree possible, we used validated psychosocial instruments which had been previously used in populations of isiZulu-speaking children in KZN (Killian & Spencer, 2004), but the overall child instrument was long (more than 45 minutes) and included questions on four other domains in addition to the psychosocial component, so we decided to use particular subscales of existing measures or, in a few cases, develop our own measures and subscales, which may limit comparability with other studies.

Conclusions

In the context of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in southern Africa, the “entangled crisis” of poverty and food insecurity exacerbated by HIV-related illness and death is having strong impacts on individuals, households, and communities. Our findings indicate that a child’s resilience and adaptation to adversity are often linked to protective factors such as family bonds and social support within the larger community and material assistance. Our findings suggest a need to strengthen child social and psychological services to support children facing economic adversity; especially girls. In contexts heavily affected by HIV/AIDS and poverty, improved understanding of the influence of age, gender and other possible mediating factors on child psychosocial well-being will help us better design interventions to support the precise physical and mental health needs of children as they mature. Life skills programs have been found to be effective for improving interpersonal skills and reducing antisocial behavior in youth (Breinbauer & others, 2005; Patel, Flisher, Nikapota, & Malhotra, 2008; van der Merwe & Dawes, 2007), and more recently, family strengthening programs have demonstrated some promise in improving communication and monitoring and control by parents and caregivers (Bell et al., 2008; Paruk, Petersen, & Bhana, 2009). Interventions to improve psychosocial well-being in the context of poverty and HIV/AIDS, however, must also address food security and general economic and social conditions. These interventions require targeting not only individuals, but also their households and communities. They must be context-specific and designed with an eye toward impact evaluation to measure the extent to which programs are working. As an example, randomized controlled trials have measured economic empowerment and school-based peer support groups on orphan mental health in Uganda, with promising outcomes (Kumakech et al., 2009; Ssewamala et al., 2009). Likewise, small cash transfers to the very poorest AIDS-affected households in Malawi appear to have important positive effects on household members of various ages in terms of health, food security, and economic well-being (Miller, Tsoka, & Reichert, 2011). Policies, programs, and interventions that attend to the economic and social needs of families and communities will be critical for supporting the psychosocial wellbeing of youth as they navigate their development within the context of being AIDS-affected and economically vulnerable.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the efforts of the members of the Amajuba Child Health and Welfare Research Project team who collected the household, caregiver and child level data and worked in the Newcastle field office.

Sources of support:

This project was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD) of the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH) under its African Partnerships program (Grant R29 HD43629).

Appendix 1

Individual questions used in psychosocial subscales, and baseline associations with orphan status

| Orphans (N=155) | Orphans (N=480) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Domain and components | No. (%) | Mean (SD) | No. (%) | Mean (SD) | p1 |

| Anxiety/Depression2,3 | |||||

| You worry about school. | 33 (21.2) | 116 (24.2) | 0.4629 | ||

| You feel lonely. | 52 (33.6) | 150 (31.3) | 0.5935 | ||

| You feel your [parents/caregiver] don’t like you. | 21 (13.6) | 55 (11.5) | 0.4862 | ||

| You feel like hiding from other people. | 20 (12.9) | 64 (13.3) | 0.8902 | ||

| You feel sad. | 38 (24.5) | 84 (17.5) | 0.0541 | ||

| You feel like crying. | 33 (21.3) | 69 (14.4) | 0.0417 | ||

| You feel that no one cares about you. | 21 (13.60 | 76 (15.8) | 0.4921 | ||

| You feel sick. | 46 (29.7) | 134 (27.9) | 0.6726 | ||

| You have nightmares. | 38 (24.5) | 130 (27.1) | 0.529 | ||

| You feel like hurting yourself. | 9 (5.8) | 29 (6.0) | 0.9146 | ||

| You feel that other kids don’t like you. | 19 (12.3) | 91 (19.0) | 0.0555 | ||

| You feel upset about things. | 44 (28.4) | 110 (22.9) | 0.1674 | ||

| You feel tired. | 43 (27.7) | 142 (29.6) | 0.6612 | ||

| You feel you are no good. | 30 (19.4) | 51 (10.6) | 0.0046 | ||

| You have trouble paying attention in class. | 29 (18.7) | 86 (17.9) | 0.8238 | ||

| You feel sorry for yourself. | 42 (27.1) | 99 (20.6) | 0.0922 | ||

| You feel worried. | 37 (23.9) | 89 (18.5) | 0.1484 | ||

| You get stomachaches. | 47 (30.3) | 138 (28.8) | 0.7082 | ||

| You feel bored. | 45 (29.0) | 136 (28.3) | 0.8672 | ||

| You feel nothing you do helps anyone. | 21 (13.6) | 71 (14.8) | 0.7024 | ||

| You have trouble sleeping | 35 (22.6) | 105 (21.9) | 0.8539 | ||

| Oppositional (Round 2) | |||||

| You fight a lot. | 23 (15.2) | 72 (17.1) | 0.5966 | ||

| You feel life is not fair. | 37 (24.5) | 100 (23.8) | 0.8531 | ||

| You feel angry. | 38 (25.2) | 101 (24.0) | 0.7729 | ||

| You feel like you are bad. | 25 (16.6) | 52 (12.4) | 0.1944 | ||

| Your parents/caregiver get angry with you. | 32 (21.1) | 64 (15.2) | 0.0914 | ||

| You bully other children. | 9 (6.0) | 28 (7.0) | 0.7674 | ||

| You have taken things that do not belong to | 20 (12.1) | 20 (13.3) | 0.7179 | ||

| You argue with your parents | 15 (9.9) | 55 (13.1) | 0.3144 | ||

| You fight with your siblings. | 32 (21.1) | 87 (20.7) | 0.8912 | ||

| You talk back to adults. | 10 (6.6) | 26 (6.2) | 0.8464 | ||

| Self esteem (Round 2) | |||||

| You feel happy. | 70 (46.4) | 212 (50.4) | 0.3995 | ||

| You feel important. | 70 (46.4) | 206 (48.9) | 0.5875 | ||

| You feel like playing with other children. | 91 (60.3) | 258 (61.3) | 0.826 | ||

| You feel loved. | 77 (51.0) | 218 (51.8) | 0.8681 | ||

| You feel like talking to other children. | 102 (67.6) | 249 (59.1) | 0.069 | ||

| You feel like having fun. | 51 (33.8) | 159 (37.8) | 0.383 | ||

| You like to help others. | 102 (67.6) | " | 0.0857 | ||

| Children like to play with you | 87 (57.6 | 243 (57.7) | 0.9823 | ||

| You have lots of fun with your parents/caregiver | 59 (39.3) | 196(46.5) | 0.1128 | ||

| You like everyone you know | 92 (60.9 | 236 (56.1) | 0.2996 | ||

| You are as happy as most children | 97 (64.2) | 272 (64.6) | 0.9351 | ||

| Resilience (Round 2) | |||||

| You are a responsible person. | 77 (51.0) | 224 (53.2) | 0.6406 | ||

| You can work well with your hands. | 107 (70.9) | 280 (66.5) | 0.3271 | ||

| You have confidence in yourself. | 107 (70.9) | 295 (70.1) | 0.8556 | ||

| You are confident of doing things on your own. | 89 (58.9) | 241 (57.2) | 0.7177 | ||

| You are optimistic about the future. | 112 (74.2) | 300 (71.3) | 0.4942 | ||

| You can do things as well as other kids | 74 (49.0) | 220 (52.3) | 0.4934 | ||

| You always tell the truth | 50 (33.1) | 155 (36.8) | 0.4158 | ||

P-values from chi-square tests for categorical variables.

Baseline for anxiety/depression: N=635, for oppositional, self esteem, and resilience: N=572.

For anxiety/depression and oppositional, % responding “always” or “often”; for self esteem and resilience, % responding “always”

Footnotes

Because of the interaction in this model, it appears that orphan status is a significant predictor of oppositional behavior, but statistically, if an interaction term is present in a model, the significance of one of the components of the included interaction is not interpretable. As noted, in the stratified results, among non-orphans, girls had higher oppositional scores than boys.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Actuarial Society of South Africa. ASSA2003 AIDS and Demographic model: Orphan projections by province 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Atwine B, Cantor-Graae E, Bajunirwe F. Psychological distress among AIDS orphans in rural Uganda. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61(3):555–564. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badcock-Walters P, Heard W, Wilson D. Developing District-Level Early Warning and Decision Support Systems to Assist in Managing and Mitigating the Impact of HIV/AIDS on Education; Barcelona. XIV International AIDS Conference.2002. [Google Scholar]

- Barbarin OA, Richter L. Economic status, community danger and psychological problems among South African children. Childhood. 2001;8(1):115–133. doi: 10.1177/0907568201008001007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battle J. Culture-Free Self Esteem Inventories-2nd edition: Examiner’s manual. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bell CC, Bhana A, Petersen I, McKay MM, Gibbons R, Bannon W, Amatya A. Building protective factors to offset sexually risky behaviors among black youths: a randomized control trial. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2008;100(8):936. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31408-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Mancini AD. The human capacity to thrive in the face of potential trauma. Pediatrics. 2008;121(2):369–375. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breinbauer C, et al. Youth: Choices and change: Promoting healthy behaviors in adolescents. Vol. 594. Pan American Health Org; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J. Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children (TSCC) Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cluver L, Gardner F. The mental health of children orphaned by AIDS: a review of international and southern African research. Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2007;19(1):1–17. doi: 10.2989/17280580709486631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluver L, Gardner F, Operario D. Psychological distress amongst AIDS-orphaned children in urban South Africa. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48(8):755–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluver L, Orkin M. Cumulative risk and AIDS-orphanhood: Interactions of stigma, bullying and poverty on child mental health in South Africa. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69(8):1186–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluver LD, Gardner F, Operario D. Effects of stigma on the mental health of adolescents orphaned by AIDS. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42(4):410–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluver Lucie D, Orkin M, Gardner F, Boyes ME. Persisting mental health problems among AIDS-orphaned children in South Africa. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluver Lucie, Fincham DS, Seedat S. Posttraumatic stress in AIDS-orphaned children exposed to high levels of trauma: the protective role of perceived social support. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2009;22(2):106–112. doi: 10.1002/jts.20396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates J, Webb P, Houser R. Measuring food insecurity: Going beyond indicators of income and anthropometry. Washington, D.C: Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Connell C, Nord M, Lofton K, Yadrick K. Food security of older children can be assessed using a standardized survey instrument. Journal of Nutrition. 2004;134(10):2566–2572. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.10.2566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyranowski JM, Frank E, Young E, Shear MK. Adolescent onset of the gender difference in lifetime rates of major depression: a theoretical model. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57(1):21. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delva W, Vercoutere A, Loua C, Lamah J, Vansteelandt S, De Koker P, Claeys P, et al. Psychological well-being and socio-economic hardship among AIDS orphans and other vulnerable children in Guinea. AIDS Care. 2009;21(12):1490–1498. doi: 10.1080/09540120902887235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Basic Education. Report on the 2008 General Household Survey (GHS): Education focus. Republic of South Africa: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. National HIV and syphilis antenatal sero-prevalence survey in South Africa 2007. Republic of South Africa: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Doku PN. Parental HIV/AIDS status and death, and children’s psychological wellbeing. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2009;3(1):26. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-3-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drimie S, Casale M. Multiple stressors in southern Africa: The link between HIV/AIDS, food insecurity, poverty and children’s vulnerability, now and in the future. AIDS Care. 2009;21(S1):28–33. doi: 10.1080/09540120902942931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ, Horwood LJ. Risk factors and life processes associated with the onset of suicidal behaviour during adolescence and early adulthood. Psychological Medicine. 2000;30(01):23–39. doi: 10.1017/s003329179900135x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Ahern J, Nandi A, Tracy M, Beard J, Vlahov D. Urban neighborhood poverty and the incidence of depression in a population based cohort study. Annals of Epidemiology. 2007;17(3):171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability–transactional stress theory. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127(6):773. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaggwa EB, Hindin MJ. The psychological effect of orphanhood in a matured HIV epidemic: An analysis of young people in Mukono, Uganda. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70(7):1002–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killian B, Spencer D. An evaluation of a group therapy programme for vulnerable children, MA Thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg. University of KwaZulu-Natal; Pietermaritzburg: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kloep M. Love is all you need? Focusing on adolescents’ life concerns from an ecological point of view. Journal of Adolescence. 1999;22(1):49–63. doi: 10.1006/jado.1998.0200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumakech E, Cantor-Graae E, Maling S, Bajunirwe F. Peer-group support intervention improves the psychosocial well-being of AIDS orphans: Cluster randomized trial. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68(6):1038–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laraia BA, Siega-Riz AM, Gundersen C, Dole N. Psychosocial factors and socioeconomic indicators are associated with household food insecurity among pregnant women. The Journal of Nutrition. 2006;136(1):177–182. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.1.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XM, Naar-King S, Barnett D, Stanton B, Fang XY, Thurston C. A developmental psychopathology framework of the psychosocial needs of children orphaned by HIV. Janac-Journal of the Association of Nurses in Aids Care. 2008;19(2):147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear-models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Luthar S. Vulnerability and resilience: A study of high-risk adolescents. Child Development. 1991;62:600–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makame V, Ani C, Grantham-McGregor S. Psychological well-being of orphans in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. Acta Paediatrica. 2002;91(4):459–465. doi: 10.1080/080352502317371724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D, Hansell S. Adolescent competence, psychological well-being, and self-assessed physical health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1987;28(4):364–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CM, Tsoka M, Reichert K. The impact of the Social Cash Transfer Scheme on food security in Malawi. Food Policy. 2011;36(2):230–238. [Google Scholar]

- Monasch R, Boerma JT. Orphanhood and childcare patterns in sub-Saharan Africa: an analysis of national surveys from 40 countries. AIDS. 2004;18:S55–S65. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200406002-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague M, Enders C, Dietz S, Dixon J, Cavendish WM. A longitudinal study of depressive symptomology and self-concept in adolescents. Journal of Special Education. 2008;42(2):67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Nyamukapa CA, Gregson S, Lopman B, Saito S, Watts HJ, Monasch R, Jukes MCH. HIV-Associated orphanhood and children’s psychosocial distress: Theoretical framework tested with data from Zimbabwe. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(1):133–141. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.116038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panday, Makiwane, Ranchod, Letsoala . Teenage pregnancy in South Africa: with a specific focus on school-going learners (Commissioned by UNICEF on behalf of Department of Education) South Africa: Human Sciences Research Council; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Paruk Z, Petersen I, Bhana A. Facilitating health-enabling social contexts for youth: qualitative evaluation of a family-based HIV-prevention pilot programme. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2009;8(1):61–68. doi: 10.2989/AJAR.2009.8.1.7.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Flisher AJ, Nikapota A, Malhotra S. Promoting child and adolescent mental health in low and middle income countries. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2008;49(3):313–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen I, Bhana A, Myeza N, Alicea S, John S, Holst H, McKay M, et al. Psychosocial challenges and protective influences for socio-emotional coping of HIV+ adolescents in South Africa: a qualitative investigation. AIDS Care. 2010;22(8):970–978. doi: 10.1080/09540121003623693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkerton J, Dolan P. Family support, social capital, resilience and adolescent coping. Child and Family Social Work. 2007;12(3):219–228. [Google Scholar]

- Prenoveau JM, Zinbarg RE, Craske MG, Mineka S, Griffith JW, Epstein AM. Testing a hierarchical model of anxiety and depression in adolescents: A tri-level model. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2010;24(3):334–344. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds W. RADS-2, Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale professional manual. 2. Lutz, FL: Psycholigical Assessment Resources; 2002. p. 172. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Casares M, Thombs BD, Rousseau C. The association of single and double orphanhood with symptoms of depression among children and adolescents in Namibia. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;18(6):369–376. doi: 10.1007/s00787-009-0739-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk KD. Community interventions providing care and support to orphans and vulnerable children: a review of evaluation evidence. AIDS Care. 2009;21(7):918–942. doi: 10.1080/09540120802537831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmiege SJ, Khoo ST, Sandler IN, Ayers TS, Wolchik SA. Symptoms of internalizing and externalizing problems - Modeling recovery curves after the death of a parent. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;31(6):S152–S160. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr L, Varrall R, Mueller J, Richter L, Wakhweya A, Adato M, Belsey M, et al. A systematic review on the meaning of the concept “AIDS Orphan”: confusion over definitions and implications for care. AIDS Care. 2008;20(5):527–536. doi: 10.1080/09540120701867248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ssewamala FM, Han CK, Neilands TB. Asset ownership and health and mental health functioning among AIDS-orphaned adolescents: Findings from a randomized clinical trial in rural Uganda. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69(2):191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa. General Household Survey 2007. Pretoria, Cape Town: StatsSA; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M, Schut H, Stroebe W. Health outcomes of bereavement. Lancet. 2007;370(9603):1960–1973. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61816-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurman TR, Snider L, Boris N, Kalisa E, Mugarira EN, Ntaganira J, Brown L. Psychosocial support and marginalization of youth-headed households in Rwanda. Aids Care-Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of Aids/Hiv. 2006;18(3):220–229. doi: 10.1080/09540120500456656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurman TR, Snider L, Boris N, Kalisa E, Nkunda ME, Ntaganira J, Brown L. Psychosocial support and marginalization of youth-headed households in Rwanda. AIDS Care. 2006;18(3):220–229. doi: 10.1080/09540120500456656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourangeau R. Cognitive aspects of survey methodology: Building a bridge between disciplines. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1984. Cognitive sciences and survey methods; pp. 73–100. [Google Scholar]

- van der Merwe A, Dawes A. Youth violence: A review of risk factors, causal pathways and effective intervention. Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2007;19(2):95–113. doi: 10.2989/17280580709486645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke G, Molenberghs G. Linear mixed models for longitudinal data. New York: Springer-Verlag, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wood K, Chase E, Aggleton P. “Telling the truth is the best thing”: teenage orphans’ experiences of parental AIDS-related illness and bereavement in Zimbabwe. Social Science & Medicine (1982) 2006;63(7):1923–1933. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]