Abstract

The UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs) and sulfotransferases (SULTs) represent major phase II drug-metabolizing enzymes that are also responsible for maintaining cellular homeostasis by metabolism of several endogenous molecules. Perturbations in the expression or function of these enzymes can lead to metabolic disorders and improper management of xenobiotics and endobiotics. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) represents a spectrum of liver damage ranging from steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and cirrhosis. Because the liver plays a central role in the metabolism of xenobiotics, the purpose of the current study was to determine the effect of human NAFLD progression on the expression and function of UGTs and SULTs in normal, steatosis, NASH (fatty), and NASH (not fatty/cirrhosis) samples. We identified upregulation of UGT1A9, 2B10, and 3A1 and SULT1C4 mRNA in both stages of NASH, whereas UGT2A3, 2B15, and 2B28 and SULT1A1, 2B1, and 4A1 as well as 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphosulfate synthase 1 were increased in NASH (not fatty/cirrhosis) only. UGT1A9 and 1A6 and SULT1A1 and 2A1 protein levels were decreased in NASH; however, SULT1C4 was increased. Measurement of the glucuronidation and sulfonation of acetaminophen (APAP) revealed no alterations in glucuronidation; however, SULT activity was increased in steatosis compared with normal samples, but then decreased in NASH compared with steatosis. In conclusion, the expression of specific UGT and SULT isoforms appears to be differentially regulated, whereas sulfonation of APAP is disrupted during progression of NAFLD.

Introduction

The liver is regarded as the primary organ of drug metabolism and utilizes two categories of enzymes to metabolize xenobiotics in an effort to facilitate their removal from the body. These consist of phase I enzymes that perform oxidative, reductive, or hydrolytic reactions that expose or introduce a functional group on a xenobiotic, and phase II conjugative enzymes that lead to the addition of bulky, generally more water-soluble entities directly onto a xenobiotic or to a product of phase I metabolism. The importance of the liver at the center of drug metabolism is exemplified by the multiplicity and redundancy of the enzymes that it expresses. Normally, these enzymes work to aid in the removal of xenobiotics from the body, thus reducing the potential for toxicity; however, they can sometimes lead to formation of a toxic metabolite (King et al., 2000; Gamage et al., 2006; Zamek-Gliszczynski et al., 2006). The occurrence of liver disease in an individual can alter the expression and function of these enzymes and complicate the drug metabolism process, leading to either inadequate processing of xenobiotics thereby potentiating their effects in the body, enhanced bioactivation to toxic metabolites, or accelerated metabolism with the potential to reduce therapeutic efficacy.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a chronic, progressive liver disease that begins as steatosis and can progress to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and even cirrhosis (Marra et al., 2008; Sanyal, 2011). NAFLD originates as simple steatosis that is characterized by accumulation of lipid droplets in >5% of hepatocytes and is largely considered benign but not quiescent (Marra et al., 2008). Steatosis may remain benign for several years; however, once progression to NASH occurs, further progression to cirrhosis is believed to be accelerated (Rubinstein et al., 2008). Progression to the more severe state of NASH is proposed to occur by several different mechanisms that ultimately result in significant liver damage in the form of greater lipid accumulation, inflammation, oxidative stress, hepatocellular damage, and varying degrees of fibrosis (Marra et al., 2008; Brunt and Tiniakos, 2010). NAFLD has been estimated to affect 17–40% of the adult population, whereas the prevalence of NASH is estimated to range anywhere from 5.7 to 17% (Ali and Cusi, 2009; McCullough, 2011). Alarmingly, it is believed that 15–25% of patients with NAFLD will develop cirrhosis, 30% of whom will die within 10 years after diagnosis (Rubinstein et al., 2008; McCullough, 2011). Due to its progressive nature and its appreciable effects on liver histopathology, NAFLD is poised to have a significant impact on xenobiotic metabolism. Our laboratory has endeavored to understand the effect of NAFLD on drug metabolism in an effort to predict the potential for toxicity or altered therapeutic effect in patients. Previous investigations have identified alterations in the expression and function of cytochrome P450 enzymes as well as diminished glutathione transferase function in a bank of human tissues representing progressive stages of NAFLD (Fisher et al., 2009; Hardwick et al., 2010). However, little is known regarding the effect of human NAFLD on the phase II enzymes UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs) or sulfotransferases (SULTs) (Merrell and Cherrington, 2011).

The UGTs are perhaps the most important family of phase II enzymes, and are responsible for metabolizing approximately 40–70% of drugs (Jancova et al., 2010). They are divided into four families: UGT1, 2, 3 and 8, with 1 and 2 being the most prominent in drug metabolism; however, not all isoforms are expressed in the liver (King et al., 2000; Bock, 2010; Jancova et al., 2010). UGTs reside in the endoplasmic reticulum and catalyze the conjugation of primarily glucuronic acid (with the exception of the UGT3 and 8 families) to xenobiotics, bile acids, steroid hormones, bilirubin, and eicosanoids using the cofactor uridine 5′-diphosphoglucuronic acid (UDP-GlcUA) (King et al., 2000; Bock, 2010; Meech and Mackenzie, 2010). The SULT enzymes are another important group of phase II enzymes that consists of four families in humans: SULT1, 2, 4, and 6 (Jancova et al., 2010). Drug-metabolizing SULTs are located in the cytosol and catalyze the transfer of sulfonate to xenobiotics, bile acids, steroid hormones, and neurotransmitters via the cofactor 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS) (Gamage et al., 2006; Zamek-Gliszczynski et al., 2006). The SULTs tend to dominate at low concentrations due to higher affinity; while the UGTs prevail at high substrate concentrations, which are saturating for SULTs, or when the availability of the SULT cofactor, PAPS, is exhausted (Zamek-Gliszczynski et al., 2006). In the current study, we have determined the effect of human NAFLD progression on the expression and function of several UGT and SULT isoforms.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Tris, EDTA, potassium chloride, sodium pyrophosphate, potassium phosphate, Brij 58 (polyethylene glycol hexadecyl ether, polyoxyethylene (20) cetyl ether), UDP-GlcUA, MgCl2, acetaminophen (APAP), perchloric acid, PAPS, dithiothreitol (DTT), bovine serum albumin (BSA), high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)–grade methanol, HPLC-grade water, and acetic acid were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Human Liver Samples.

Frozen adult human liver tissue was obtained from the National Institutes of Health–funded Liver Tissue Cell Distribution System coordinated through the University of Minnesota (Minneapolis, MN), Virginia Commonwealth University (Richmond, VA), and the University of Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh, PA). All samples were scored and categorized by a medical pathologist within the Liver Tissue Cell Distribution System according to the NAFLD Activity Score system developed by Kleiner et al. (2005), followed by confirmation via histologic examination at the University of Arizona. Donor information, including age and sex, has been previously published for most samples (Fisher et al., 2009). Information for additional samples that have recently been added to the tissue bank can be found in Supplemental Table 1. The samples were diagnosed as either normal (n = 20), steatotic (n = 12), NASH with fatty liver (NASH fatty, n = 16), and NASH without fatty liver (NASH not fatty/cirrhosis, n = 20). Samples exhibiting >10% fatty infiltration of hepatocytes were considered steatotic, whereas those with >5% fatty infiltration of hepatocytes in addition to significant inflammation and fibrosis were categorized as NASH (fatty). Samples were categorized as NASH (not fatty) when fatty deposits within hepatocytes were reduced < 5% and accompanied by more marked inflammation and fibrotic branching. Representative histology images have been published previously (Fisher et al., 2009; Hardwick et al., 2010; Hardwick et al., 2011).

Total RNA Isolation.

Total RNA was isolated from human liver tissue using RNAzol B reagent (Tel-Test Inc., Friendswood, TX) per the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA integrity was confirmed by ethidium bromide staining after agarose gel electrophoresis. RNA concentrations were determined by UV spectrophotometry.

QuantiGene Plex 2.0 Assay for mRNA Quantification.

All reagents for analysis including lysis buffer, amplifier/label probe diluent, and substrate solution were supplied in the QuantiGene Plex 2.0 assay kit (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). Total RNA was mixed with master mix containing lysis mixture, blocking reagent, capture beads, and 2.0 specific probe set, in a hybridization plate. After approximately 18 hours of hybridization at 54°C in Vortemp 56 (Labnet International, Woodbridge, NJ), the contents were transferred to a flat bottom magnetic plate. The washing at this step and all subsequent washings were performed on a Bioplex Pro II wash station (BioRad, Hercules, CA). The hybridization complex beads were then incubated with preamplifier, amplifier, and label probe for 1 hour each, followed by incubation with streptavidin phycoerythrin (SAPE) for 30 minutes. After incubation with SAPE, the plate was washed with SAPE wash buffer followed by re-suspension of the beads. The resulting fluorescence was read on a Bioplex multiple array reader system (BioRad). The raw data were obtained from Bioplex Manager 5.0 software (BioRad).

Cellular Fractionation for Protein Analysis.

Cytosolic and microsome fractions of human liver tissue were prepared by homogenization of approximately 300 mg tissue in 3 ml buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1 mM EDTA, and 154 mM potassium chloride with 1 Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail tablet (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) per 25 ml at 4°C. Homogenates were centrifuged at 10,000g for 30 minutes. The supernatant was transferred to clean centrifuge tubes and the centrifugation step repeated. The resulting supernatant was then transferred to clean ultracentrifuge tubes and the samples were centrifuged at 100,000g for 70 minutes. The supernatant was retained as the cytosolic fraction. The remaining pellet was re-suspended in a buffer containing 100 mM sodium pyrophosphate (pH 7.4) and 1 mM EDTA. The samples were then centrifuged at 100,000g for 70 minutes and the supernatant was discarded. The remaining pellet was re-suspended with minimal sonication on ice in a buffer containing 10 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.4), 1 mM EDTA, and 20% glycerol. This re-suspension was retained as the microsome fraction. Crude membrane fractions of human liver tissue were prepared by homogenization of approximately 250 mg tissue in 2.5 ml buffer containing 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) and 1 Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail tablet (Roche) per 25 ml. Samples were transferred to clean ultracentrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 100,000g for 60 minutes. The supernatant was discarded and the remaining pellet re-suspended in Tris buffer. The re-suspension was retained as the crude membrane fraction. Protein concentrations for all cellular fractions were determined using the Pierce BCA protein quantitation assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunoblot Analysis.

Microsomal (UGTs, 20 µg/well) or cytosolic (SULTs, 20 μg/well) proteins from all samples were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide electrophoresis on 7.5% Tris-HCl gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes overnight. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against UGT1A1 and 1A6, as well as mouse monoclonal antibodies against UGT2B10 and SULT1A1, were obtained from Abcam, Inc. (Cambridge, MA). A mouse polyclonal antibody was obtained from Abnova (Taipei, Taiwan) to detect UGT1A9. SULT1C4 and 2A1 were detected using rabbit polyclonal antibodies obtained from Abnova and Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), respectively. Pan-Cadherin was detected using a rabbit polyclonal antibody acquired from Abcam, Inc. and used as a control protein for microsomal proteins (UGTs). Goat polyclonal antibodies against extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 (sc-93) and 2 (sc-154) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and used to detect total extracellular signal-regulated kinase, which served as a control protein for cytosolic proteins (SULTs). Primary antibody incubations were performed overnight at 4°C followed by secondary detection the next day. Quantification of relative protein expression was determined using image processing and analysis with Image J software (NIH, Bethesda, MD) and normalized to control protein.

Analysis of UGT and SULT Activity Using APAP as a Probe Substrate.

Hepatic glucuronidation and sulfation of APAP was performed as previously described (Manautou et al., 1996; Reisman et al., 2009) with slight modifications. Glucuronidation was assessed by adding 50 µl 0.05% Brij58 to 250 µg hepatic crude membrane protein in glass test tubes. Solutions of 25 mM UDP-GlcUA and 50 mM MgCl2 in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) were added to the samples and then preincubated at room temperature for 10 minutes. Upon addition of APAP, tubes were incubated in a 37°C water bath for 60 minutes. The final 500 µl reaction volume contained 0.5 mg/ml crude membrane protein, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM APAP, and 4 mM UDP-GlcUA in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer. Reactions were stopped by addition of 50 µl 6% perchloric acid. Samples were chilled on ice and centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Fifty microliters of collected supernatants were injected onto the HPLC for analysis. APAP-glucuronide (APAP-GLUC) formation was confirmed by conducting control incubations lacking APAP, crude membrane proteins, or UDP-GlcUA in which no APAP-GLUC metabolite was formed. Quantification of the APAP-GLUC peak was achieved by comparing peak areas of APAP-GLUC metabolite with an authentic APAP-GLUC standard (McNeil-PPC, Inc., Fort Washington, PA) and expressed as nanomoles APAP-GLUC formed per minute per milligram protein.

Sulfonation of APAP was performed by adding 125 µl PAPS and 50 µl DTT containing 0.5% BSA in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (w/v, pH 7.8) to empty borosilicate glass test tubes. In addition, 250 µg cytosolic protein was added to each tube and diluted with 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer to a total volume of 350 µl. Samples were placed in a 37°C water bath and 50 µl APAP solution was added and mixed gently. Total reaction volume (400 µl final volume) contained 0.625 mg/ml cytosolic protein, 1 mM APAP, 8 mM DTT, 0.0625% BSA, and 0.1 mM PAPS. Reactions were stopped after 120 minutes by adding 400 µl ice cold methanol. Samples were then centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 minutes at 4°C and 50 µl of collected supernatant was analyzed by HPLC. APAP-sulfate (APAP-SULF) formation was confirmed by conducting control incubations lacking APAP, cytosolic proteins, or PAPS in which no APAP-SULF metabolite was formed. Quantification of the APAP-SULF peak was achieved by comparing peak areas of APAP-SULF metabolite with an authentic APAP-SULF standard (McNeil-PPC, Inc.) and expressed as picomoles APAP-SULF formed per minute per milligram protein.

All HPLC analyses were performed using a Shimadzu LC-6AD pump with a SPD-20A UV-Vis detector (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Inc., Columbia, MD) at 254 nm. A 250 × 4.6 mm Ultrasphere C18 column with 5 µm particle size (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) was used. The flow of mobile phase (12.5% methanol: 1% acetic acid in water) was maintained at a rate of 1.2 ml/min.

Statistical Analysis.

Gene expression data were normalized to the housekeeping gene, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. To achieve normality of the data. After glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase normalization, all data were log-transformed. To determine significant changes in individual gene expression, the log-transformed mRNA data were analyzed by analysis of variance followed by the Tukey honest significant difference test. Relative protein levels and enzyme activity data were not transformed; however, all data were analyzed by an analysis of variance followed by the Tukey honest significant difference test. A significance level of P ≤ 0.05 was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Gene Expression of UGT and SULT Isoforms during Progression of Human NAFLD.

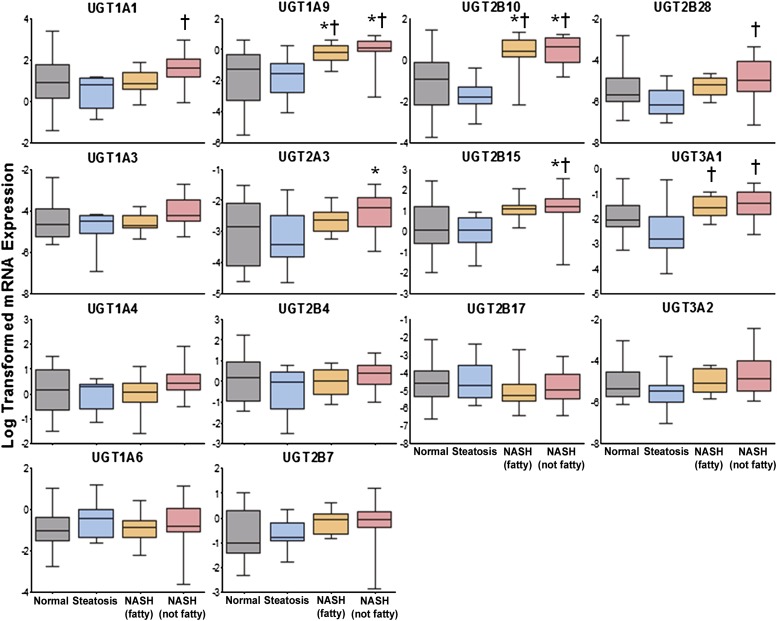

The mRNA expression of several UGT and SULT isoforms was determined by an Affymetrix Plex 2.0 Assay in normal, steatosis, NASH (fatty), and NASH (not fatty) human samples and expressed in Figs. 1 and 2, respectively. UGT isoforms investigated included 1A1, 1A3, 1A4, 1A6, 1A9, 2B4, 2B7, 2B10, 2B15, 2B17, 2B28, 3A1, and 3A2. Overall, expression of many UGT genes tended to decrease in steatosis although these changes were not significant. UGT1A1 and 2B28 were significantly upregulated in NASH (not fatty) samples compared with steatosis, whereas UGT1A9 and 2B10 were elevated in both stages of NASH compared with normal and steatosis. UGT3A1 gene expression was increased in both stages of NASH compared with steatosis. UGT2A3 expression was increased in NASH (not fatty) samples compared with normal; however, 2B15 was elevated in NASH (not fatty) compared with both normal and steatosis.

Fig. 1.

Log-transformed relative mRNA expression of UGT isoforms in human NAFLD. Relative mRNA levels of UGT1A1, 1A3, 1A4, 1A6, 1A9, 2A3, 2B4, 2B7, 2B10, 2B15, 2B17, 2B28, 3A1, and 3A2 in human liver samples diagnosed as normal, steatotic, NASH (fatty), and NASH (not fatty) are shown. Total RNA was isolated and measured by the Quantigene 2.0 Assay for RNA analysis. Data were normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and presented as log-transformed relative mRNA expression. Asterisk (*) indicates significant difference from normal and dagger (†) indicates significance from steatosis (P ≤ 0.05).

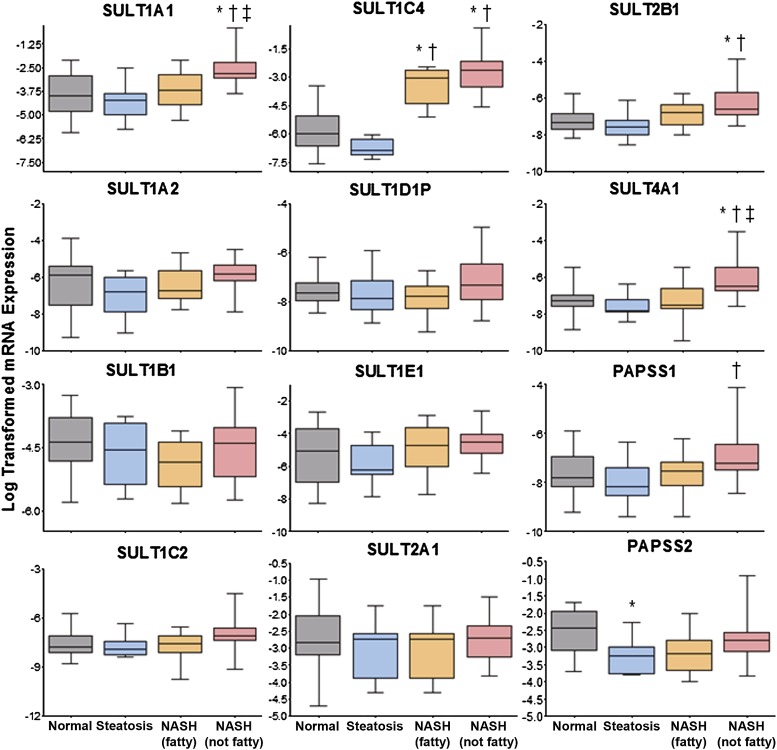

Fig. 2.

Log-transformed relative mRNA expression of SULT isoforms in human NAFLD. Relative mRNA levels of SULT1A1, 1A2, 1B1, 1C2, 1C4, 1D1P, 1E1, 2A1, 2B1, 4A1, and PAPSS1 and PAPSS2 (PAPS synthase 2) in human liver samples diagnosed as normal, steatotic, NASH (fatty), and NASH (not fatty) are shown. Total RNA was isolated and measured by the Quantigene 2.0 Assay for RNA analysis. Data were normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and presented as log-transformed relative mRNA expression. Asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference from normal, dagger (†) indicates significance from steatosis, and double dagger (‡) indicates significance from NASH (fatty) with a significance level of P ≤ 0.05.

SULT and related genes investigated included 1A1, 1A2, 1B1, 1C2, 1C4, 1E1, 2A1, 2B1, 4A1, the pseudogene 1D1P, PAPSS1 (PAPS synthase 1), and PAPS synthase 2. Few gene expression changes were observed in the SULT family of enzymes, and no overarching trends were apparent; however, changes in specific SULT genes were noted. In particular, SULT1A1 and 4A1 were upregulated in NASH (not fatty) samples compared with all other groups (normal, steatosis, and NASH fatty), whereas SULT1C4 expression was increased in both stages of NASH compared with both normal and steatosis. SULT2B1 was elevated in end-stage NASH (not fatty) samples compared with both normal and steatosis. Upon examination of the PAPS-forming enzymes, upregulation of PAPSS1 was noted in NASH (not fatty) samples compared with steatosis, and PAPS synthase 2 was decreased in steatosis compared with normal.

Protein Levels of Specific UGT and SULT Isoforms in Human NAFLD.

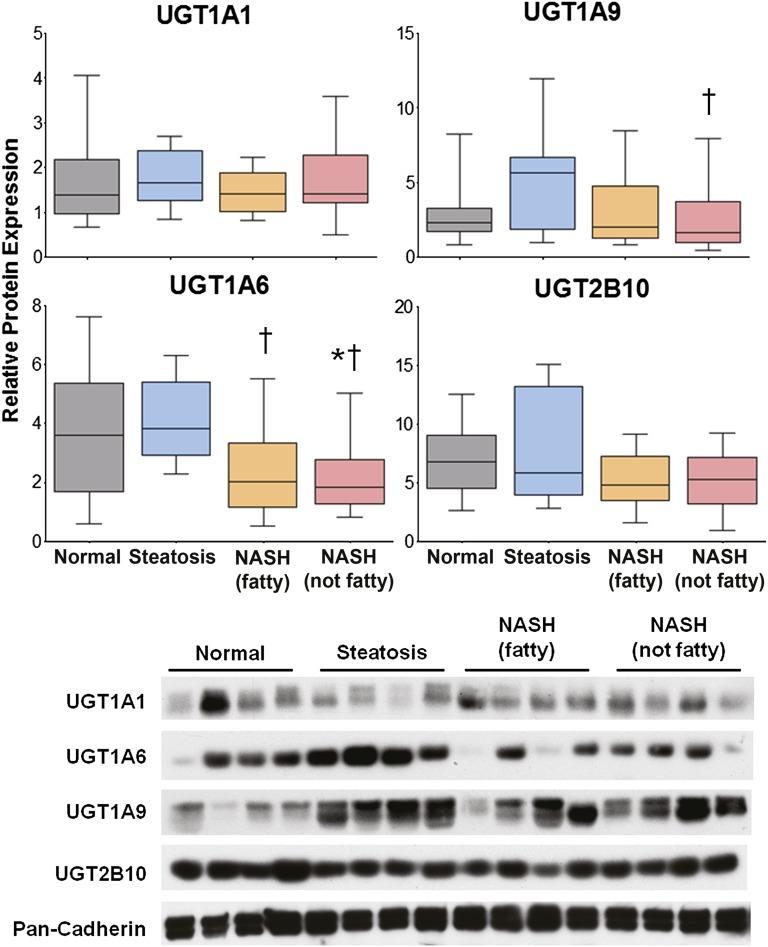

Relative protein levels of UGT1A1, 1A6, 1A9, and 2B10 were determined by immunoblot and densitometric analysis. The densitometric results of all samples in the study are shown in Fig. 3 with representative immunoblots depicting four samples from each disease category. No alterations in UGT1A1 protein levels, one of the isoforms responsible for the metabolism of APAP, were observed throughout progression of NAFLD. In addition, protein levels of UGT2B10, which metabolizes polyunsaturated fatty acids (Bock, 2010), were unaltered during the progression of NAFLD. UGT1A6 protein levels were measured due to its ability to glucuronidate APAP. NASH (fatty) samples exhibited a significant downregulation of UGT1A6 protein compared with steatosis. UGT1A6 protein was also decreased in NASH (not fatty) samples compared with both normal and steatosis. UGT1A9, which also metabolizes APAP, exhibited a significant decrease in protein levels in NASH (not fatty) samples compared with steatosis.

Fig. 3.

Relative protein levels of UGT1A1, 1A6, 1A9, and 2B10 in human NAFLD. Representative immunoblots of hepatic UGT1A1, 1A6, 1A9, and 2B10 protein levels are shown with pan-Cadherin as control and four samples from each diagnostic category as follows: normal, steatosis, NASH (fatty), and NASH (not fatty). Relative protein levels of all samples in the study were determined by densitometric analysis and expressed as relative to pan-Cadherin. Asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference from normal and dagger (†) indicates significance from steatosis (P ≤ 0.05).

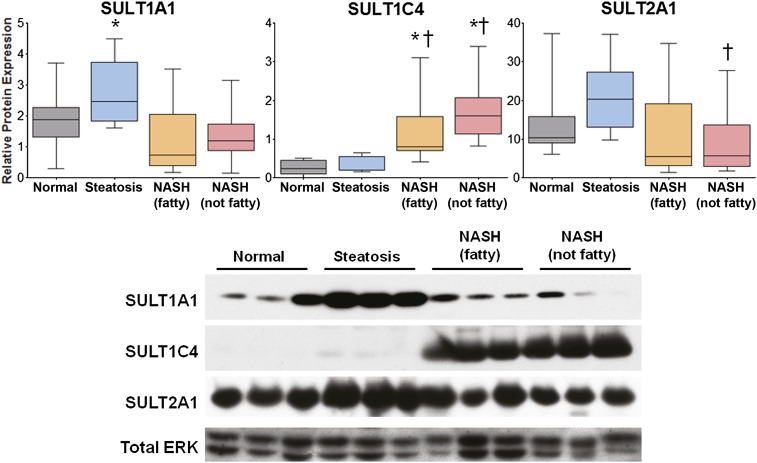

Relative protein levels of SULT1A1, 1C4, and 2A1 were determined by immunoblot and densitometric analysis. The densitometric results of all samples in the study are shown in Fig. 4, with representative immunoblots depicting three samples from each disease category. SULT1A1 is the primary isoform responsible for sulfonation of APAP. SULT1A1 protein was elevated in steatosis compared with normal, but decreased in both stages of NASH compared with steatosis. SULT1C4 has long been considered a primarily fetal protein (Gamage et al., 2006; Riches et al., 2009). Protein levels of SULT1C4 were investigated due to the striking upregulation of SULT1C4 mRNA observed in both stages of NASH (see Fig. 2). In the current study, protein levels of SULT1C4 were significantly increased in both stages of NASH compared with both normal and steatosis. Protein levels of SULT2A1 were investigated due to its prominence in drug metabolism and high expression in normal human liver (Riches et al., 2009). Although SULT2A1 protein levels appeared to increase in steatosis, these findings were not statistically significant; however, SULT2A1 protein was significantly decreased in NASH (not fatty) samples compared with steatosis.

Fig. 4.

Relative protein levels of SULT1A1, 1C4, and 2A1 in human NAFLD. Representative immunoblots of hepatic SULT1A1, 1C4, and 2A1 protein levels are shown, with total extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) as control and four samples from each diagnostic category as follows: normal, steatosis, NASH (fatty), and NASH (not fatty). Relative protein levels of all samples in the study were determined by densitometric analysis and expressed as relative to total ERK. Asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference from normal and dagger (†) indicates significance from steatosis (P ≤ 0.05).

Effect of Human NAFLD on the Glucuronidation and Sulfonation of APAP.

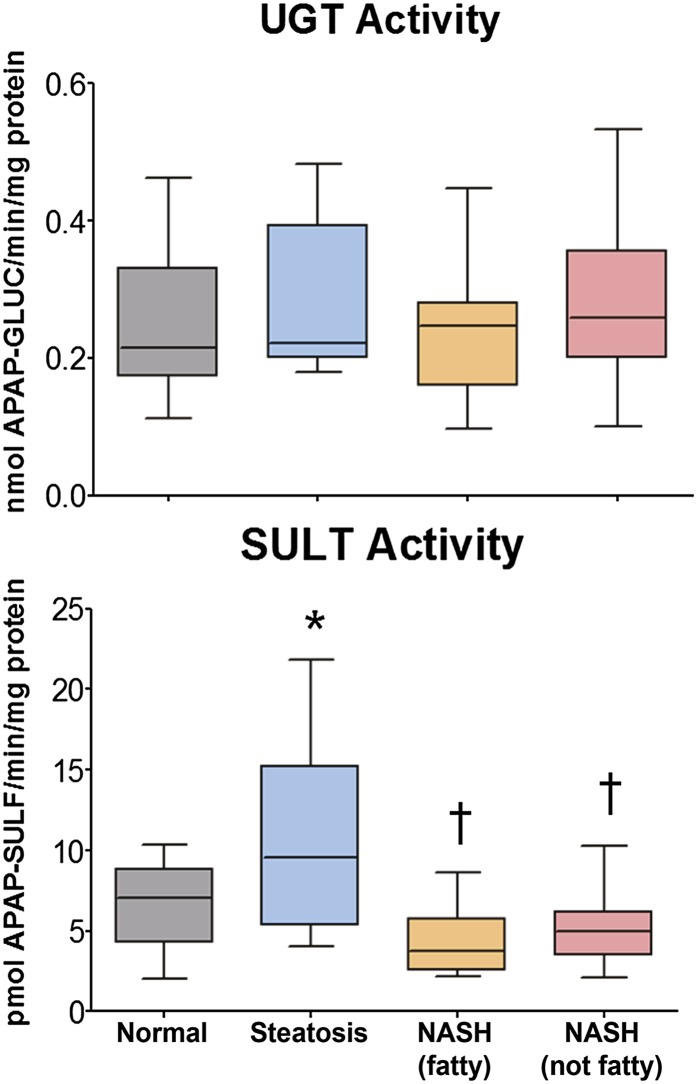

UGT activity was determined by reaction of human liver crude membrane preparations with APAP and measurement of APAP-GLUC by HPLC analysis. The results, expressed as nanomoles APAP-GLUC formed per minute per milligram protein, are shown in Fig. 5. No alterations in the ability of UGT enzymes to glucuronidate APAP were observed in any stage of NAFLD. SULT activity was determined by incubation of human liver cytosol preparations with APAP and measurement of APAP-SULF by HPLC analysis. The results are shown in Fig. 5, and expressed as picomoles APAP-SULF formed per minute per milligram protein. APAP-SULF formation was significantly increased in steatotic samples compared with normal. In contrast, both stages of NASH exhibited a significant decrease in the ability to sulfonate APAP compared with steatotic samples.

Fig. 5.

Enzymatic activity of multiple UGT and SULT isoforms against the substrate APAP. Activity of pan-UGT isoforms was performed in human liver microsomes against APAP and expressed as nanomoles APAP-GLUC formed per minute per milligram protein. Activity of multiple SULT isoforms was determined in human liver cytosol preparations against APAP and expressed as picomoles APAP-SULF formed per minute per milligram protein. Asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference from normal and dagger (†) indicates a significant difference from steatosis (P ≤ 0.05).

Discussion

Phase II conjugation enzymes are critically important in the management of several xenobiotics due to their ability to significantly increase the mass and hydrophilicity of a substrate (Zamek-Gliszczynski et al., 2006). The UGTs and SULTs represent two prominent classes of phase II enzymes because they transform a large proportion of drugs and endogenous molecules, including bilirubin, steroid hormones, bile acids, eicosanoids, and neurotransmitters (Gamage et al., 2006; Zamek-Gliszczynski et al., 2006; Bock, 2010; Jancova et al., 2010). Conjugation via UGTs can result in inactivation, formation of pharmacologically active metabolites, or generation of acyl glucuronides with significant potential for toxicity (Zamek-Gliszczynski et al., 2006; Bock, 2010). Cytosolic SULTs are responsible for the metabolism of small, endogenous molecules and drugs, whereas the carbohydrate and chondroitin SULTs in the Golgi apparatus are important in maintaining cellular homeostasis through sulfonation of macromolecules including lipids, proteins, and glycosaminoglycans (Gamage et al., 2006). Similar to the UGTs, SULT reactions can lead to detoxication as well as bioactivation (Gamage et al., 2006). The SULTs are credited with coordination of high-affinity reactions that dominate at low concentrations, whereas the UGTs prevail at high substrate concentrations (Zamek-Gliszczynski et al., 2006). This is primarily due to the limited stores of the SULT cofactor PAPS, synthesized by PAPSS1 and 2, and largely dependent on the availability of sulfate (Zamek-Gliszczynski et al., 2006). Stores of hepatic UDP-GlcUA, which is the cofactor for most UGT enzymes, are much higher than that of PAPS, thus allowing for high-capacity metabolism (Zamek-Gliszczynski et al., 2006; Meech and Mackenzie, 2010; MacKenzie et al., 2011). UGT1A1, 1A3, 1A4, 1A6, 1A9, 2B7, and 2B15 and SULT1A1, 1B1, 1E1, and 2A1 are considered most important for drug metabolism; however, perturbations in the expression or function of any isoform can result in significant consequences not only for drug metabolism but also cellular homeostasis (Riches et al., 2009; Miners et al., 2010).

Liver disease has traditionally been associated with decreased elimination of drugs; however, even in patients with cirrhosis, glucuronidation appears to be maintained while the typical downregulation of cytochrome P450 activity seen with high levels of inflammation is readily apparent (Debinski et al., 1995). Although no studies have investigated the direct effect of human NAFLD progression on UGT expression and function, some studies have indicated a decrease in mRNA of specific isoforms with increasing levels of hepatic inflammation including 1A4, 2B4, and 2B7 (Congiu et al., 2002; Aitken et al., 2006). However, it is known that the mRNA expression of specific UGT isoforms does not always coincide with levels of the subsequent protein due to differential translation efficiency, splicing, or post-translational modifications (Court, 2010). Investigation of human NAFLD progression on SULT expression and function is also lacking. However, studies in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and cirrhosis patients, both of which can arise from NAFLD, have indicated a decreased ratio of APAP-GLUC to APAP-SULF in HCC patients and only a slight decrease in those with cirrhosis which the authors attributed to increased SULT1A1 activity (Wang et al., 2010). Others have used a proteomics approach and identified a reduction in SULT1A1 protein in HCC that was verified by immunoblot analysis and measurement of activity using p-nitrophenol (Yeo et al., 2010). The current study indicates an increase in mRNA of specific UGT and SULT isoforms in the more severe, inflammatory stage of NASH, but an overall lack of changes in UGT and SULT mRNA expression at the earlier stage of steatosis.

Currently, we identified an increase in UGT1A9 mRNA in both stages of NASH. UGT1A9 is known for metabolism of bulky phenols while also being infamous for conversion of carboxylic acids to acyl-O-glucuronides, some of which can readily form protein adducts (King et al., 2000; Ritter, 2000). This enzyme has been shown to conjugate several xenobiotic carboxylic acids and phenols, including APAP, naproxen, furosemide, fenoprofen, and ibuprofen (Ritter, 2000; Bock, 2010). Upregulation of UGT1A9 mRNA in NASH creates potential for enhanced formation of acyl-O-glucuronides, but is dependent on subsequent upregulation of protein and activity. UGT1A1, another important enzyme in drug metabolism, is also responsible for metabolism of endogenous molecules such as estradiol, catecholestrogens, polyunsaturated fatty acids, all-trans retinoic acid, and arachidonic acid (Ritter, 2000; Bock, 2010; Miners et al., 2010). Perhaps most importantly, UGT1A1 is the sole enzyme responsible for metabolism of bilirubin, a product of heme degradation, and lack of functional 1A1 protein can result in moderate to severe hyperbilirubinemia (Bock, 2010). Like UGT1A9, 1A1 is able to metabolize APAP as well as buprenorphine and etoposide (King et al., 2000; Miners et al., 2010). We identified an increase in UGT1A1 mRNA above normal, steatosis, and NASH (fatty) samples in the NASH (not fatty/cirrhosis) group, indicating the potential for increased metabolism via 1A1. However, we found very little changes in either UGT1A9 or 1A1 protein levels, suggesting little potential for altered glucuronidation mediated by these isoforms. Furthermore, investigation of mRNA levels of UGT1A6, which is also capable of metabolizing APAP, revealed no alterations in transcriptional regulation due to NAFLD progression, but a significant decrease in protein levels in both stages of NASH. In the current study, overall glucuronidation activity toward APAP as assessed at a single concentration and time point in crude membrane preparations revealed no significant alterations in the glucuronidation of APAP at any stage of NAFLD. However, the studies by Court et al. (2001) identified UGT1A9 as the predominant isoform in the glucuronidation of APAP at clinically relevant concentrations. Collectively, the relative protein levels of UGT1A1, 1A6, and particularly 1A9 are congruent with the ex vivo enzyme activity assay, further supporting the conclusion that NAFLD progression does not significantly alter the glucuronidation of APAP.

Investigation of the various SULTs revealed alterations in two unlikely isoforms: 1C4 and 4A1. The SULT1C family has traditionally been considered fetal enzymes, but has recently been shown to be important for estradiol and catecholestrogen metabolism (Adjei and Weinshilboum, 2002; Hui et al., 2008; Lindsay et al., 2008). Moreover, they are believed to be involved in thyroid hormone regulation, and have a role in the metabolism of oral contraceptives (Yasuda et al., 2005; Lindsay et al., 2008). SULT1C4 mRNA and protein levels were elevated in both stages of NASH. However, the transcriptional regulation and pathologic importance of SULT1C4 in liver disease are largely unknown, and its role in NASH warrants future investigation. Another interesting and perplexing discovery was the upregulation of SULT4A1 mRNA in NASH (not fatty/cirrhosis). SULT4A1 is almost exclusively expressed in brain, and is very highly conserved among species although it has no known endogenous ligand (Gamage et al., 2006; Minchin et al., 2008). One study has shown an elevation in hepatic SULT4A1 expression after ventromedial hypothalamic lesions, which are known to cause significant disruptions in metabolic homeostasis manifesting as obesity and hyperinsulinemia similar to that seen in metabolic syndrome, an accompanying feature of NAFLD (King, 2006; Kiba et al., 2009; McCullough, 2011). Expression of hepatic SULT4A1 during metabolic syndrome and currently in NASH is a novel discovery, and its function in the context of liver disease is potentially an exciting new avenue of investigation.

There were only a few critical changes observed in the major drug-metabolizing SULTs in the current study. We identified no alteration in SULT2A1 at the transcriptional level, but found a reduction in SULT2A1 protein levels in NASH (not fatty/cirrhosis). In contrast, SULT1A1 mRNA, the most dominant isoform found in the liver (Gamage et al., 2006), was significantly elevated in end-stage NASH (not fatty/cirrhosis) samples; however, SULT1A1 protein was elevated in steatosis, but decreased in both stages of NASH. The influence of SULT1A1 on the metabolism of APAP cannot be understated, and is reflected in the current study. SULT activity in NAFLD directly mirrored the observed changes in SULT1A1 protein, resulting in increased metabolism in steatosis and diminished capacity of APAP sulfonation in NASH. These findings are complementary to our studies in a rodent model of NASH in which the excretion of APAP-SULF into both plasma and bile was decreased, suggesting a reduction in APAP sulfonation (Lickteig et al., 2007). Currently, we have identified a reduction in APAP-SULF formation in human NASH samples (see Fig. 5) via an ex vivo activity analysis of liver cytosols, despite ample supplementation of the cofactor PAPS. This indicates an alteration in the basal function of SULT enzymes, primarily SULT1A1.

This is the first study to investigate and identify alterations in the expression and function of multiple UGT and SULT isoforms in the progressive stages of human NAFLD. Overall, we have found minimal alterations in individual UGTs and their activity during human NAFLD progression; however, several changes in the expression and function of specific SULT enzymes suggest significant perturbations with disease progression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Institutes of Health-funded Liver Tissue Cell Distribution System for continued assistance and procurement of liver tissue samples from patients with various stages of NAFLD. The authors especially extend sincere appreciation to Marion Namenwirth (University of Minnesota), Melissa Thompson (Virginia Commonwealth University), and Dr. Stephen C. Strom and Kenneth Dorko (University of Pittsburgh).

Abbreviations

- APAP

acetaminophen

- APAP-GLUC

APAP-glucuronide

- APAP-SULF

APAP-sulfate

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- LTCDS

Liver Tissue Cell Distribution System

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- PAPS

3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphosulfate

- PAPSS1

PAPS synthase 1

- SAPE

streptavidin phycoerythrin

- SULT

sulfotransferase

- UDP-GlcUA

uridine 5′-diphosphoglucuronic acid

- UGT

UDP-glucuronosyltransferase

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Hardwick, Cherrington.

Conducted experiments: Hardwick, Ferreira, More, Lake.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Manautou, Slitt.

Performed data analysis: Hardwick, Ferreira, More, Lu.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Hardwick, Ferreira, More, Manautou, Slitt, Cherrington.

Footnotes

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health [Grants DK068039, ES006694, AT002842, and HD062489]; and the Liver Tissue Cell Distribution System was supported by the National Institutes of Health [Contract N01-DK-7-0004/HHSN267200700004C].

This article has supplemental material available at dmd.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at dmd.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Adjei AA, Weinshilboum RM. (2002) Catecholestrogen sulfation: possible role in carcinogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 292:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitken AE, Richardson TA, Morgan ET. (2006) Regulation of drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters in inflammation. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 46:123–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali R, Cusi K. (2009) New diagnostic and treatment approaches in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Ann Med 41:265–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock KW. (2010) Functions and transcriptional regulation of adult human hepatic UDP-glucuronosyl-transferases (UGTs): mechanisms responsible for interindividual variation of UGT levels. Biochem Pharmacol 80:771–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunt EM, Tiniakos DG. (2010) Histopathology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol 16:5286–5296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congiu M, Mashford ML, Slavin JL, Desmond PV. (2002) UDP glucuronosyltransferase mRNA levels in human liver disease. Drug Metab Dispos 30:129–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Court MH, Duan SX, von Moltke LL, Greenblatt DJ, Patten CJ, Miners JO, Mackenzie PI. (2001) Interindividual variability in acetaminophen glucuronidation by human liver microsomes: identification of relevant acetaminophen UDP-glucuronosyltransferase isoforms. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 299:998–1006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Court MH. (2010) Interindividual variability in hepatic drug glucuronidation: studies into the role of age, sex, enzyme inducers, and genetic polymorphism using the human liver bank as a model system. Drug Metab Rev 42:209–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debinski HS, Lee CS, Danks JA, Mackenzie PI, Desmond PV. (1995) Localization of uridine 5′-diphosphate-glucuronosyltransferase in human liver injury. Gastroenterology 108:1464–1469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CD, Lickteig AJ, Augustine LM, Ranger-Moore J, Jackson JP, Ferguson SS, Cherrington NJ. (2009) Hepatic cytochrome P450 enzyme alterations in humans with progressive stages of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Drug Metab Dispos 37:2087–2094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamage N, Barnett A, Hempel N, Duggleby RG, Windmill KF, Martin JL, McManus ME. (2006) Human sulfotransferases and their role in chemical metabolism. Toxicol Sci 90:5–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardwick RN, Fisher CD, Canet MJ, Lake AD, Cherrington NJ. (2010) Diversity in antioxidant response enzymes in progressive stages of human nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Drug Metab Dispos 38:2293–2301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardwick RN, Fisher CD, Canet MJ, Scheffer GL, Cherrington NJ. (2011) Variations in ATP-binding cassette transporter regulation during the progression of human nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Drug Metab Dispos 39:2395–2402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui Y, Yasuda S, Liu MY, Wu YY, Liu MC. (2008) On the sulfation and methylation of catecholestrogens in human mammary epithelial cells and breast cancer cells. Biol Pharm Bull 31:769–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jancova P, Anzenbacher P, Anzenbacherova E. (2010) Phase II drug metabolizing enzymes. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 154:103–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiba T, Kintaka Y, Suzuki Y, Nakata E, Ishigaki Y, Inoue S. (2009) Ventromedial hypothalamic lesions change the expression of neuron-related genes and immune-related genes in rat liver. Neurosci Lett 455:14–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King BM. (2006) The rise, fall, and resurrection of the ventromedial hypothalamus in the regulation of feeding behavior and body weight. Physiol Behav 87:221–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CD, Rios GR, Green MD, Tephly TR. (2000) UDP-glucuronosyltransferases. Curr Drug Metab 1:143–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, Behling C, Contos MJ, Cummings OW, Ferrell LD, Liu YC, Torbenson MS, Unalp-Arida A, et al. Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network (2005) Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 41:1313–1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lickteig AJ, Fisher CD, Augustine LM, Aleksunes LM, Besselsen DG, Slitt AL, Manautou JE, Cherrington NJ. (2007) Efflux transporter expression and acetaminophen metabolite excretion are altered in rodent models of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Drug Metab Dispos 35:1970–1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay J, Wang LL, Li Y, Zhou SF. (2008) Structure, function and polymorphism of human cytosolic sulfotransferases. Curr Drug Metab 9:99–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie PI, Rogers A, Elliot DJ, Chau N, Hulin JA, Miners JO, Meech R. (2011) The novel UDP glycosyltransferase 3A2: cloning, catalytic properties, and tissue distribution. Mol Pharmacol 79:472–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manautou JE, Tveit A, Hoivik DJ, Khairallah EA, Cohen SD. (1996) Protection by clofibrate against acetaminophen hepatotoxicity in male CD-1 mice is associated with an early increase in biliary concentration of acetaminophen-glutathione adducts. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 140:30–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marra F, Gastaldelli A, Svegliati Baroni G, Tell G, Tiribelli C. (2008) Molecular basis and mechanisms of progression of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Trends Mol Med 14:72–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough AJ. (2011) Epidemiology of the metabolic syndrome in the USA. J Dig Dis 12:333–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meech R, Mackenzie PI. (2010) UGT3A: novel UDP-glycosyltransferases of the UGT superfamily. Drug Metab Rev 42:45–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrell MD, Cherrington NJ. (2011) Drug metabolism alterations in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Drug Metab Rev 43:317–334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minchin RF, Lewis A, Mitchell D, Kadlubar FF, McManus ME. (2008) Sulfotransferase 4A1. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 40:2686–2691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miners JO, Mackenzie PI, Knights KM. (2010) The prediction of drug-glucuronidation parameters in humans: UDP-glucuronosyltransferase enzyme-selective substrate and inhibitor probes for reaction phenotyping and in vitro-in vivo extrapolation of drug clearance and drug-drug interaction potential. Drug Metab Rev 42:196–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisman SA, Csanaky IL, Aleksunes LM, Klaassen CD. (2009) Altered disposition of acetaminophen in Nrf2-null and Keap1-knockdown mice. Toxicol Sci 109:31–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riches Z, Stanley EL, Bloomer JC, Coughtrie MW. (2009) Quantitative evaluation of the expression and activity of five major sulfotransferases (SULTs) in human tissues: the SULT “pie”. Drug Metab Dispos 37:2255–2261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter JK. (2000) Roles of glucuronidation and UDP-glucuronosyltransferases in xenobiotic bioactivation reactions. Chem Biol Interact 129:171–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein E, Lavine JE, Schwimmer JB. (2008) Hepatic, cardiovascular, and endocrine outcomes of the histological subphenotypes of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Semin Liver Dis 28:380–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal AJ. (2011) NASH: A global health problem. Hepatol Res 41:670–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XR, Qu ZQ, Li XD, Liu HL, He P, Fang BX, Xiao J, Huang W, Wu MC. (2010) Activity of sulfotransferase 1A1 is dramatically upregulated in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma secondary to chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Cancer Sci 101:412–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda S, Suiko M, Liu MC. (2005) Oral contraceptives as substrates and inhibitors for human cytosolic SULTs. J Biochem 137:401–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo M, Na YM, Kim DK, Kim YB, Wang HJ, Lee JA, Cheong JY, Lee KJ, Paik YK, Cho SW. (2010) The loss of phenol sulfotransferase 1 in hepatocellular carcinogenesis. Proteomics 10:266–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamek-Gliszczynski MJ, Hoffmaster KA, Nezasa K, Tallman MN, Brouwer KL. (2006) Integration of hepatic drug transporters and phase II metabolizing enzymes: mechanisms of hepatic excretion of sulfate, glucuronide, and glutathione metabolites. Eur J Pharm Sci 27:447–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.